Online Media Bias and Political Participation in EU Member States; Cross-National Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. From Traditional Models to Political Participation in the Digital Age; Academic Literature and Deducing Hypotheses

1.2. Theoretical Perspectives on the Double-Edged Sword: Online Media and Its Effects on Democratic Participation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Directions, Questions, and Objectives

2.2. Data Collection and Statistical Design

- (a)

- Dependent Variable

- (b)

- Independent Variables

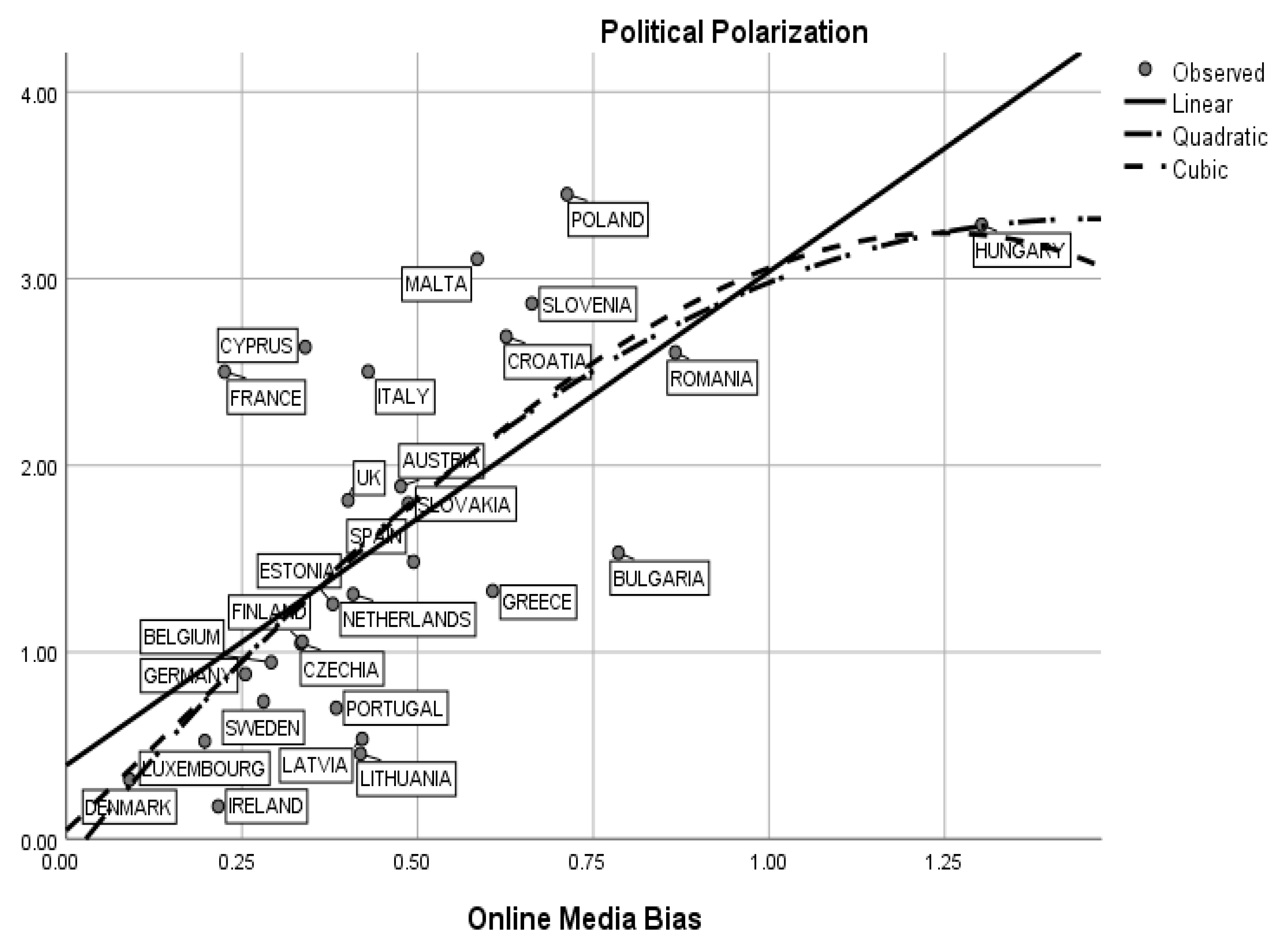

3. Results

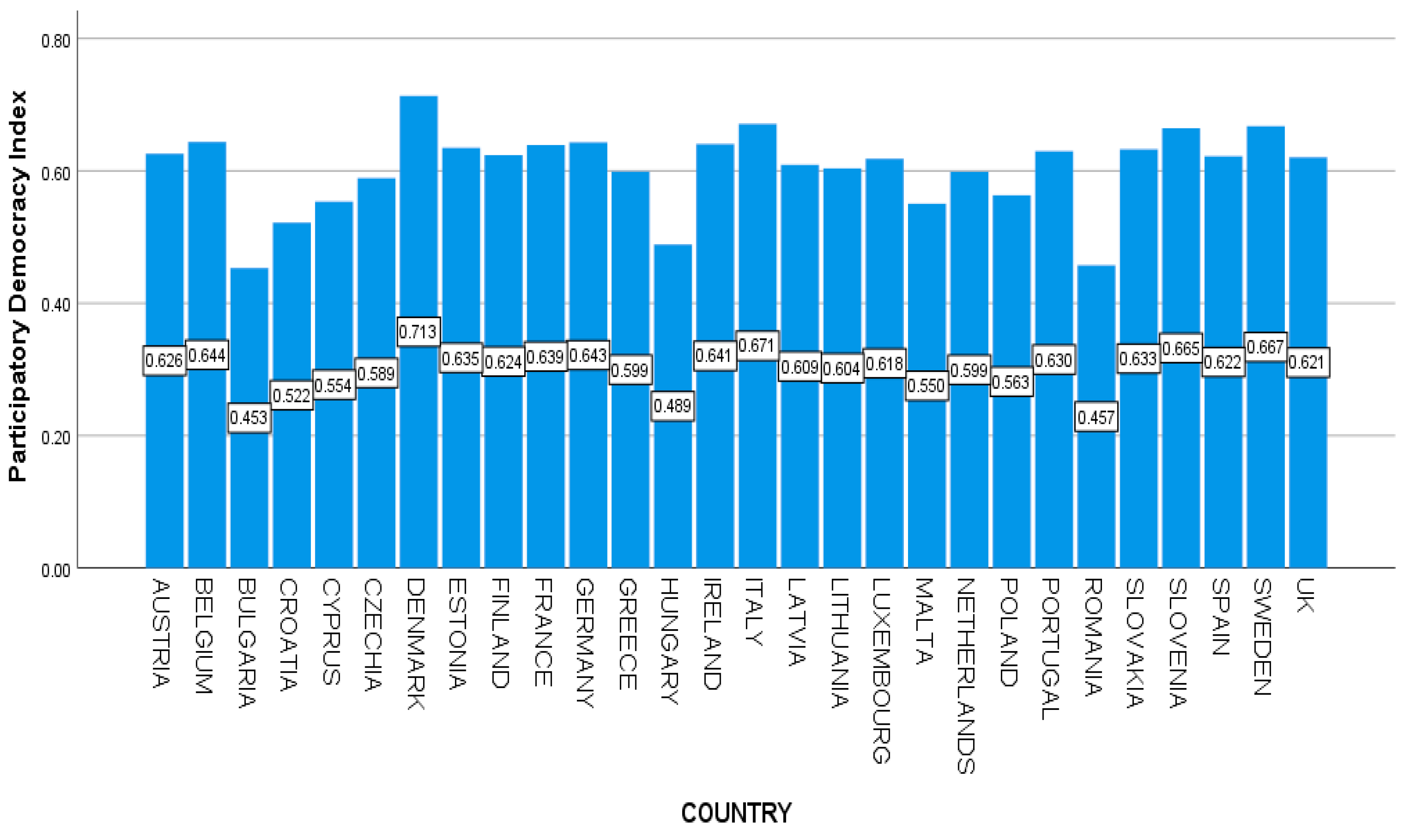

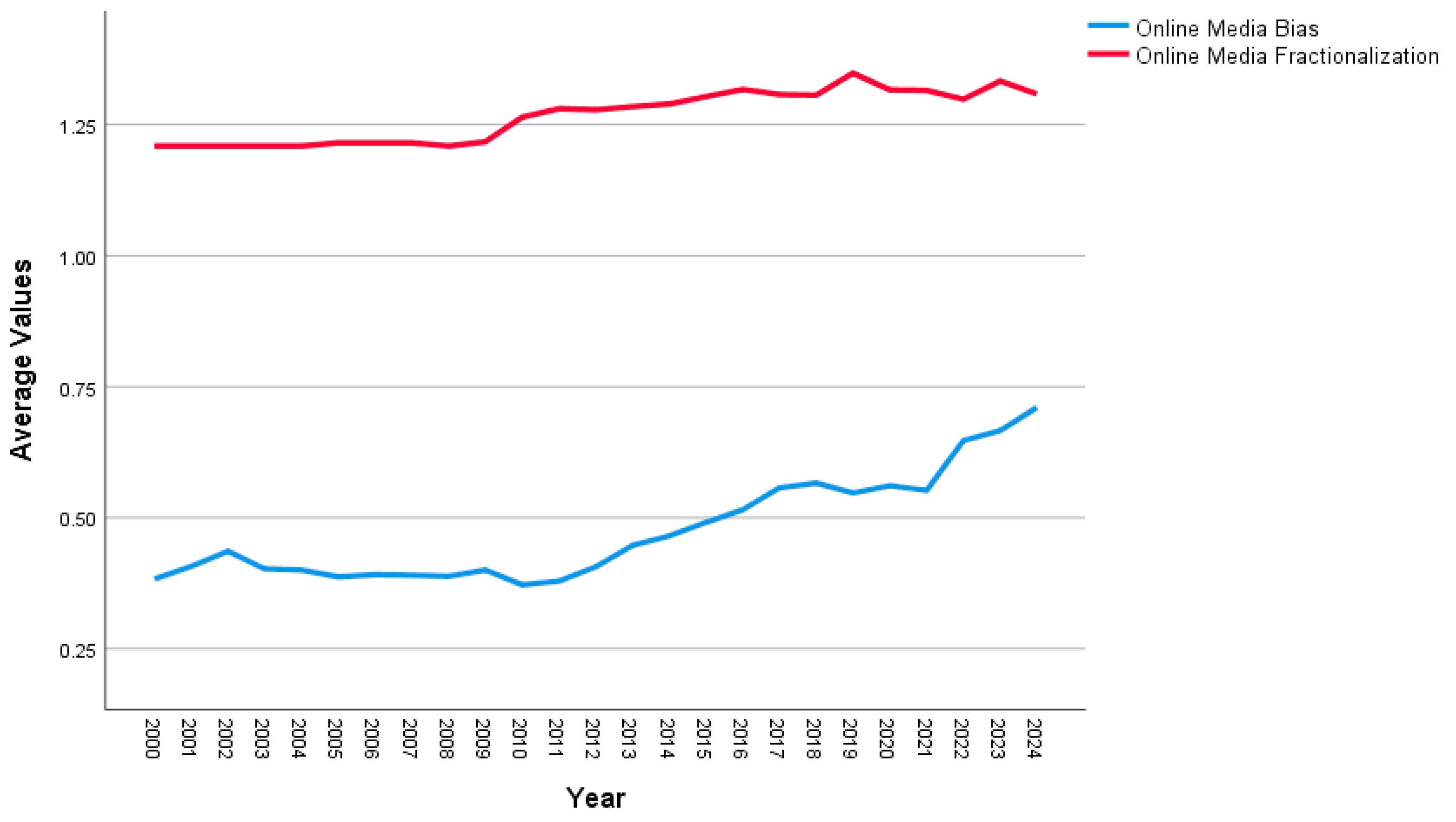

3.1. Digital Environment and Participatory Democracy Across EU Member States

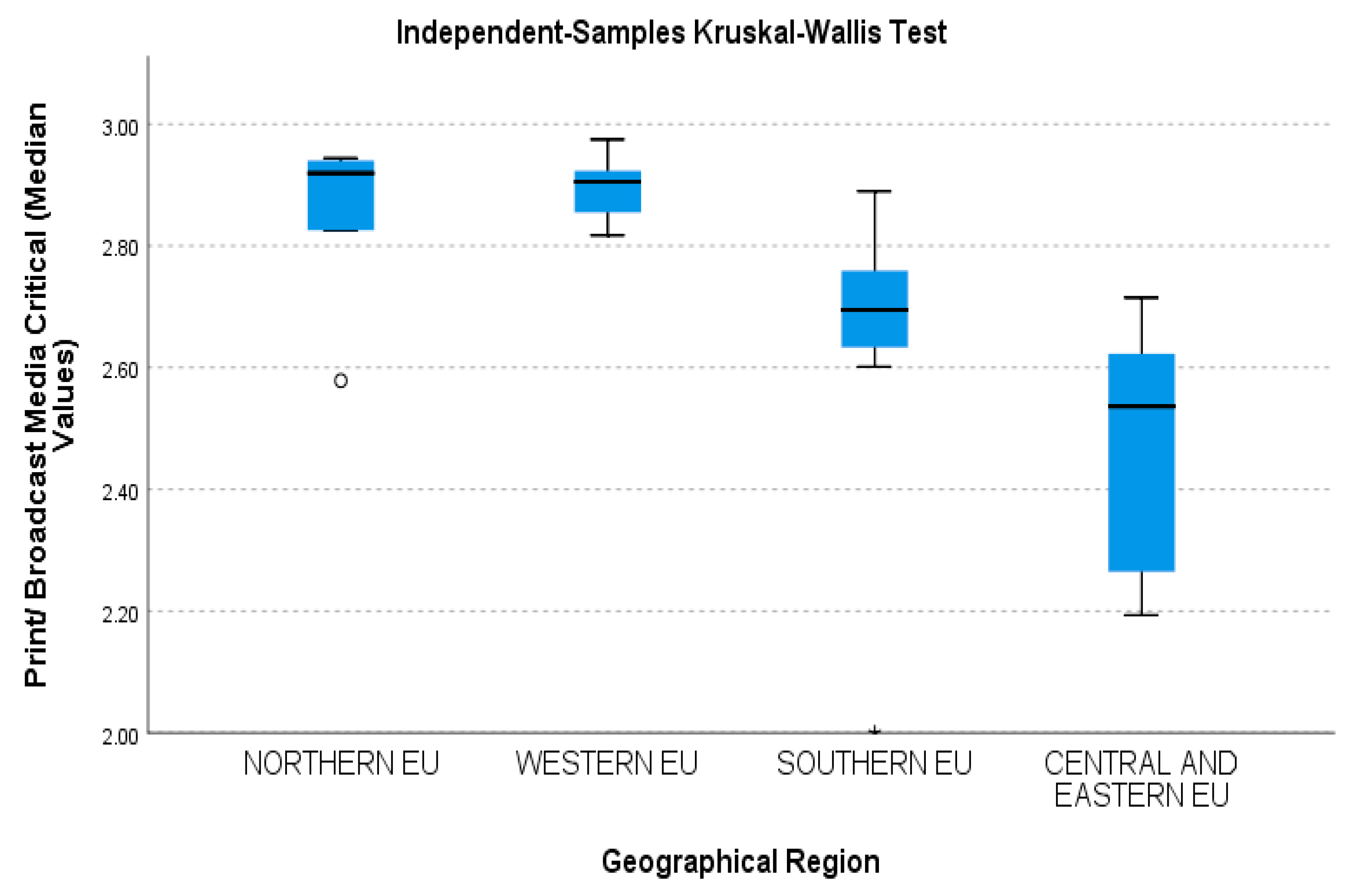

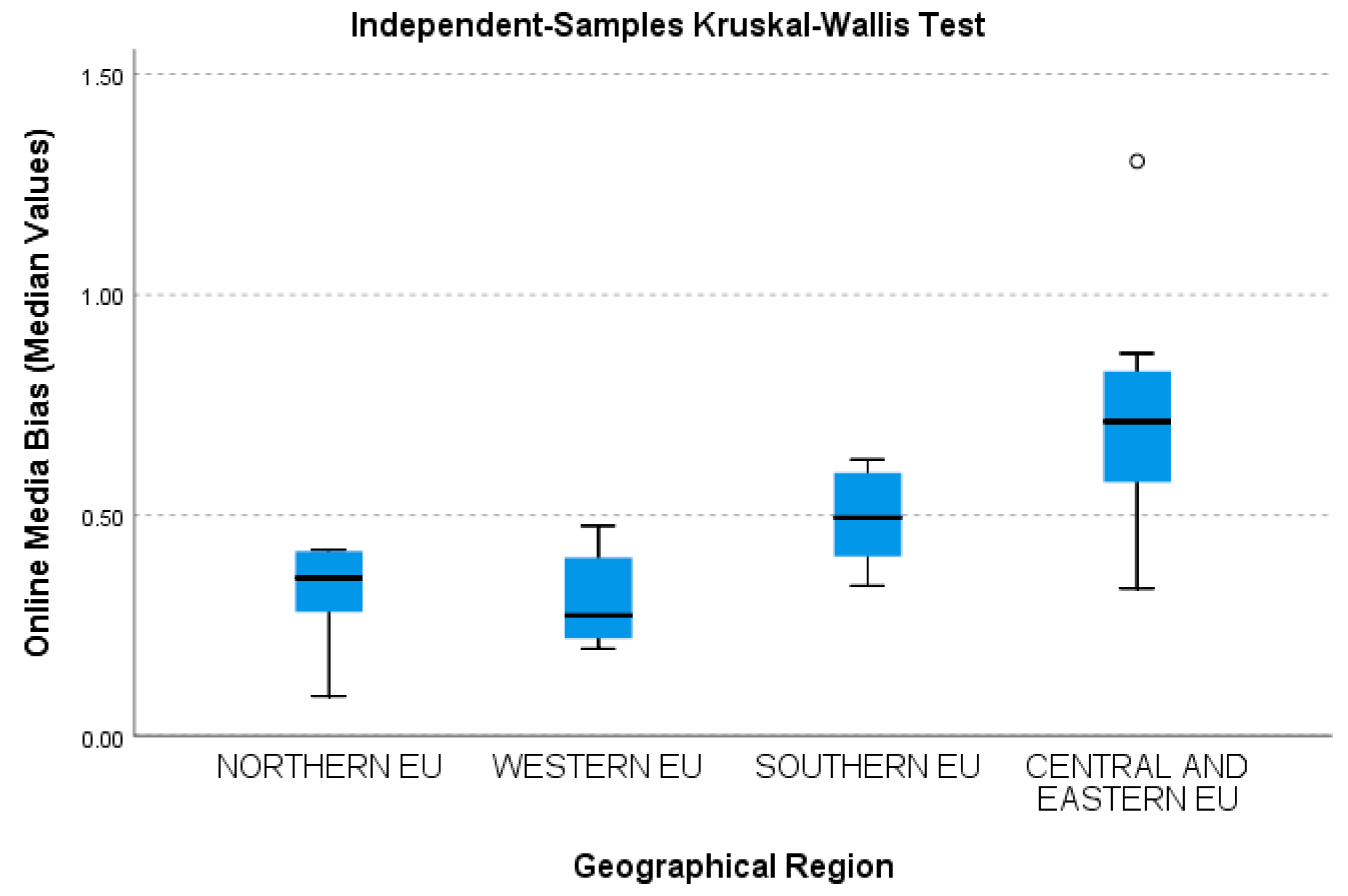

3.2. Traditional vs. Digital Media; Regional Differences

3.3. Online Media Bias, Social Media Usage, and Participatory Democracy: A Quantile Regression Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkiviadou, N. (2024). Platform liability, hate speech and the fundamental right to free speech. Information & Communications Technology Law, 34(2), 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. (2014). The press and democratic dialogue. Harvard Law Review, 127(8), 331–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ardèvol-Abreu, A., & de Zúñiga, H. G. (2017). Effects of editorial media bias perception and media trust on the use of traditional, citizen, and social media news. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(3), 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, G., Antonopoulou, H., Giotopoulos, K., & Halkiopoulos, C. (2025). Impact of information and communication technologies on democratic processes and citizen participation. Societies, 15(2), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberá, P. (2020). Social media, echo chambers, and political polarization. In N. Persily, & J. A. Tucker (Eds.), Social media and democracy: The state of the field, prospects for reform (pp. 34–55). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baym, N. K. (2010). Personal connections in the digital age. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beetham, D. (2004). The quality of democracy: Freedom as the foundation. Journal of Democracy, 15(4), 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. L., & Serrin, W. (2005). The watchdog role. In G. Overholser, & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), The press (pp. 169–188). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boccia Artieri, G., Bruns, A., Dehghan, E., & Iannelli, L. (2025). Fringe democracy and the platformization of the public sphere. Comunicazione Politica, 1, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bode, L. (2016). Political news in the news feed: Learning politics from social media. Mass Communication and Society, 19, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, S. (2009). Does internet use affect engagement? A meta-analysis of research. Political Communication, 26, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J. P. C., Cheng, S. W., Chang, S. M. J., & Su, K. P. (2025). Navigating the digital maze: A review of ai bias, social media, and mental health in generation Z. AI, 6(6), 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M., De Francisci Morales, G., Galeazzi, A., Quattrociocchi, W., & Starnini, M. (2021). The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9), e2023301118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruft, R. (2022). Journalism and press freedom as human rights. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 39(3), 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J. (1993). Rethinking the media as a public sphere. In P. Dahlgren, & C. Sparks (Eds.), Communication and citizenship (pp. 27–57). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J. (2007). Rethinking media and democracy. In R. Negrine, & J. Stanyer (Eds.), The political communication reader (pp. 27–32). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, R. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, L. (2003). Defining and developing democracy. In R. A. Dahl, I. Shapiro, & J. A. Cheibub (Eds.), The democracy sourcebook (pp. 29–39). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feenberg, A. (2002). Transforming technology: A critical theory revisited. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R., & Jarren, O. (2024). The platformization of the public sphere and its challenge to democracy. Philosophy & Social Criticism, 50(1), 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forja-Pena, T., García-Orosa, B., & López-García, X. (2024). A shift amid the transition: Towards smarter, more resilient digital journalism in the age of AI and disinformation. Social Sciences, 13(8), 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. (2007). Scales of justice: Reimagining political space in a globalizing world. Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C. (2023). Digital democracy and the digital public sphere. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- García, L. B., & Oleart, A. (2023). Regulating disinformation and big tech in the EU: A research agenda on the institutional strategies, public spheres and analytical challenges. Journal of Common Market Studies, 62(5), 1395–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R. K. (2009). Echo chambers online? Politically motivated selective exposure among internet news users. Journal of Computer–Mediated Communication, 14, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. (2018). Custodians of the internet: Platforms, content moderation, and the hidden decisions that shape social media. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilwald, A. (1993). The public sphere, the media and democracy. Transformation, 21(1), 65–77. Available online: https://transformationjournal.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/tran021005.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Giugni, M., & Grasso, M. (Eds.). (2022). The oxford handbook of political participation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gradwohl, R., Heller, Y., & Hillman, A. (2025). How social media can undermine democracy. European Journal of Political Economy, 86(1), 102634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth, A. (2007). On mill, infallibility, and freedom of expression. Res Publica, 13(1), 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoewe, J., & Peacock, C. (2020). The power of media in shaping political attitudes. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hout, M., & Maggio, C. (2021). Immigration, race & political polarization. Daedalus, 150(2), 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huckfeldt, R. R., & Sprague, J. (1995). Citizens, politics and social communication: Information and influence in an election campaign. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, L. Y. (2023). Social media, disinformation, and democracy: How different types of social media usage affect democracy cross-nationally. Democratization, 30(6), 1040–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsaniyati, H., Sarwoprasodjo, S., Muljono, P., & Gandasari, D. (2023). The use of social media for development communication and social change: A review. Sustainability, 15, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, K., & Spierings, N. (2016). Social media, parties, and political inequalities. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, F. J., Suzuki, V. P., & Hubbard, A. (2020). Social media and democracy: Fostering political deliberation and participation. Western Journal of Communication, 85(2), 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, C. K., & Kodila-Tedika, O. (2020). Does social media promote democracy? Some empirical evidence. Journal of Policy Modeling, 42(2), 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T. J., Kaye, B. K., & Lee, A. M. (2017). Blinded by the spite? Path model of political attitudes, selectivity, and social media. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 25(3), 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kubin, E., & von Sikorski, C. (2021). The role of (social) media in political polarization: A systematic review. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(3), 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümpel, A. S. (2020). The matthew effect in social media news use: Assessing inequalities in news exposure and news engagement on social network sites (SNS). Journalism, 21, 1083–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levendusky, M. S., & Malhotra, N. (2015). Does media coverage of partisan polarization affect political attitudes? Political Communication, 33(2), 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipschultz, J. H. (2018). Social media communication: Concepts, practices, data, law, and ethics (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- López-López, P. C., Barredo-Ibáñez, D., & Jaráiz-Gulías, E. (2023). Research on digital political communication: Electoral campaigns, disinformation, and artificial intelligence. Societies, 13(5), 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. (2005). The agenda-setting function of the press. In G. Overholser, & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), The press (pp. 156–168). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mellon, J., & Prosser, C. (2017). Twitter and Facebook are not representative of the general population: Political attitudes and demographics of British social media users. Research and Politics, 4(3), 205316801772000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mill, J. S. (2003). On liberty. In S. Collini (Ed.), J. S. Mill On liberty and other writings (pp. 1–117). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P. (2007). The role of the free press in promoting democratization, good governance and human development. In M. Harvey (Ed.), Media matters: Perspectives on advancing governance and development (pp. 66–75). Global Forum for Media Development, Internews Europe. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olan, F., Jayawickrama, U., Arakpogun, E. O., Suklan, J., & Liu, S. (2024). Fake news on social media: The impact on society. Information Systems Frontiers, 26, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papa, V., & Photiadis, T. (2021). Algorithmic curation and users’ civic attitudes: A study on facebook news feed results. Information, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Z. (2015). Affective publics: Sentiment, technology, and politics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter Bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquino, G. (2023). Nuovo corso di scienza politica. Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Persily, N., & Tucker, J. A. (Eds.). (2020). Social media and democracy: The state of the field, prospects for reform. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Levicán, K., & Salvo-Garrido, S. (2022). Understanding social media literacy: A systematic review of the concept and its competencies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 8807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiff, M. R. (2024). The liberal conception of free speech and its limits. Jurisprudence, 16(1), 62–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodilosso, E. (2024). Filter bubbles and the unfeeling: How AI for social media can foster extremism and polarization. Philosophy & Technology, 37(2), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rowden, J., Lloyd, D. J. B., & Gilbert, N. (2014). A model of political voting behaviours across different countries. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 413(C), 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schejter, A. M., & Tirosh, N. (2015). Seek the meek, seek the just: Social media and social justice. Telecommunications Policy, 39(9), 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuhl, R., & Picard, R. G. (2005). The marketplace of ideas. In G. Overholser, & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.), The press (pp. 141–155). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schradie, J. (2019). The revolution that wasn’t: How digital activism favors conservatives. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. P., & Carrington, P. J. (Eds.). (2011). The SAGE handbook of social network analysis. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Sievi, L., & Pawelec, M. (2025). (How) Should security authorities counter false information on social media in crises? A democracy-theoretical and ethical reflection. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 116(1), 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, N. (2002). Understanding media cultures: Social theory and mass communication (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, J. R. (2023). Was John Stuart Mill right about freedom of speech? In J. R. Stoner, J. R. Carrese, & C. McNamara (Eds.), Free speech and intellectual diversity in higher education (pp. 135–152). Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C. R. (2001). Republic.com. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C. R. (2002). The law of group polarization. Journal of Political Philosophy, 10(2), 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Going to extremes: How like minds unite and divide. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sunstein, C. R. (2018). Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taxitari, L., Sitistas, T., & Gavriil, E. (2025). “Disinformation aims to mislead; misinformation thrives in ignorance”: Insights from experts and non-experts in greek-speaking cyprus. Social Sciences, 14(3), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, K., & Wells, C. (2016). Curated flows: A framework for mapping media exposure in the digital age. Communication Theory, 26, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombetta, F., & Rossignoli, D. (2021). The price of silence: Media competition, capture, and electoral accountability. European Journal of Political Economy, 69, 101939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhoof, D., & Cannie, H. (2010). Freedom of expression and information in a democratic society. International Communication Gazette, 72(4–5), 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischmeyer, T. (2019). Making social media an instrument of democracy. European Law Journal, 25(2), 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L. (2006). Freedom of expression in the European Union. European Public Law, 12(3), 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, L. (2014). Article 11—Freedom of expression and information. In S. Peers, T. Hervey, J. Kenner, & A. Ward (Eds.), The EU charter of fundamental rights. A commentary (pp. 311–340). CH Beck, Hart Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yarchi, M., Baden, C., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2020). Political polarization on the digital sphere: A cross-platform, over-time analysis of interactional, positional, and affective polarization on social media. Political Communication, 38(1–2), 98–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeste-Piquer, E., Suau-Martínez, J., Sintes-Olivella, M., & Xicoy-Comas, E. (2025). What if i prefer robot journalists? Trust and objectivity in the AI news ecosystem. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S. W., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2019). The role of heterogeneous political discussion and partisanship on the effects of incidental news exposure online. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 16, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajonc, R. B. (2001). Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Davis, M. (2022). E-extremism: A conceptual framework for studying the online far right. New Media & Society, 26(5), 2954–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Symbol | Questions in V-Democracy Database | Scale of Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online media consumption | OMC | Do people consume domestic online media? | 0–3 |

| Social media usage for offline political actions | SMU | How often do average people use social media to organize offline political action of any kind? | 0–4 |

| Online mobilization for democracy | OMD | In this year, how frequent and large have events of mass mobilization for pro-democratic aims been? | 0–4 |

| Online media perspectives | OMP | Do the major domestic online media outlets represent a wide range of political perspectives? | 0–4 |

| Print/broadcast media critical | PBMC | Of the major print and broadcast outlets, how many routinely criticize the government? | 0–3 |

| Online media bias | OMB | Is there media bias against opposition parties or candidates? | 0–4 |

| Online media fractionalization | OMF | Do the major domestic online media outlets give a similar presentation of major (political) news? | 0–4 |

| Political polarization | PP | Is society polarized into antagonistic, political camps? | 0–4 |

| Government capacity to regulate online content | GRO | Does the government have sufficient staff and resources to regulate Internet content in accordance with existing law? | 0–4 |

| Participatory democracy index | PD | To what extent is the participatory principle achieved? | 0–1 |

| Descriptive Statistics | PD | SMU | OMC | OMD | OMP | PBMC | OMB | OMF | PP | GRO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 0.62 | 2.55 | 2.53 | 0.96 | 3.49 | 2.81 | 0.41 | 1.13 | 1.41 | 2.44 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.06 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.69 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.68 |

| Skewness | −1.02 | −0.40 | −0.89 | 1.15 | −0.49 | −1.33 | 1.56 | 0.61 | 0.36 | −0.62 |

| Kurtosis | 0.85 | −0.14 | 0.50 | 1.42 | −0.64 | 1.12 | 3.79 | −0.14 | −1.11 | −0.29 |

| Range | 0.26 | 2.48 | 1.34 | 2.88 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.21 | 2.34 | 3.28 | 2.56 |

| Minimum | 0.45 | 1.00 | 1.62 | 0.31 | 2.84 | 2.00 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.83 |

| Maximum | 0.71 | 3.48 | 2.95 | 3.18 | 3.85 | 2.98 | 1.30 | 2.58 | 3.45 | 3.38 |

| 25th percentile | 0.58 | 2.13 | 2.38 | 0.57 | 3.22 | 2.60 | 0.32 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 2.06 |

| 50th percentile | 0.62 | 2.55 | 2.53 | 0.96 | 3.49 | 2.81 | 0.41 | 1.13 | 1.41 | 2.44 |

| 75th percentile | 0.64 | 2.97 | 2.67 | 1.55 | 3.60 | 2.91 | 0.59 | 1.44 | 2.53 | 2.86 |

| Variables | Test Statistic | p (Sig.) |

|---|---|---|

| Online media consumption | 7.016 | 0.071 |

| Social media usage for offline political actions | 5.830 | 0.120 |

| Online mobilization for democracy | 8.505 | 0.037 * |

| Online media perspectives | 7.223 | 0.065 |

| Print/broadcast media critical | 16.517 | 0.001 * |

| Online media bias | 14.359 | 0.002 * |

| Online media fractionalization | 11.740 | 0.008 * |

| Political polarization | 12.096 | 0.007 * |

| Government capacity to regulate online content | 6.988 | 0.072 |

| Participatory democracy index | 6.399 | 0.094 |

| Model I | Model II | Model III | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q = 0.25 | q = 0.5 | q = 0.75 | ||||

| Parameter | p (sig.) | p (sig.) | p (sig.) | |||

| (Intercept) | 0.1 | 0.166 | 0.139 | |||

| Social media usage for offline political actions | 0.280 | <0.01 | 0.360 | 0.013 | 0.384 | <0.01 |

| Government capacity to regulate online content | 0.129 | <0.01 | 0.307 | 0.016 | 0.104 | 0.201 |

| Online mobilization for democracy | −0.215 | <0.01 | 0.205 | 0.136 | −0.107 | 0.245 |

| Online media consumption | 0.082 | 0.09 | 0.198 | 0.210 | 0.365 | 0.02 |

| Online media perspectives | 0.142 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.944 | −0.328 | 0.03 |

| Political polarization | −0.076 | 0.016 | 0.206 | 0.201 | 0.802 | <0.01 |

| Print/Broadcast media critical | 0.420 | <0.01 | 0.299 | 0.112 | 0.703 | <0.01 |

| Online media bias | −0.206 | <0.01 | −0.439 | 0.033 | −0.582 | <0.01 |

| Online media fractionalization | 0.119 | <0.01 | −0.063 | 0.684 | −0.066 | 0.529 |

| R2 | 0.670 | <0.05 | 0.522 | <0.05 | 0.418 | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grecu, S.; Mihailescu, B.C.; Vranceanu, S. Online Media Bias and Political Participation in EU Member States; Cross-National Perspectives. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030155

Grecu S, Mihailescu BC, Vranceanu S. Online Media Bias and Political Participation in EU Member States; Cross-National Perspectives. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):155. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030155

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrecu, Silviu, Bogdan Constantin Mihailescu, and Simona Vranceanu. 2025. "Online Media Bias and Political Participation in EU Member States; Cross-National Perspectives" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030155

APA StyleGrecu, S., Mihailescu, B. C., & Vranceanu, S. (2025). Online Media Bias and Political Participation in EU Member States; Cross-National Perspectives. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 155. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030155