Abstract

This systematic review analyzes the representation of older adults in the media to determine whether news coverage contributes to reinforcing or combating ageism. For societies undergoing population ageing, it is essential to understand the image of old age conveyed by the media, as they play a significant role in shaping public perception. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines were followed. In total, 21 articles addressing the media representation of old age were selected from 1435 search results across three databases: Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed. The results show that the media do not sufficiently make older adults visible, often present negative narratives about old age, and use stigmatizing terms to refer to this group. Most of the research comes from the field of sociology, mainly employs discourse analysis, and does not examine journalistic aspects such as genres, information sources, or the images accompanying news stories. In conclusion, the reviewed literature provides a valuable diagnosis of media ageism but highlights the need to broaden the disciplinary perspective and incorporate analyses and proposals aimed at transforming journalistic routines, in order to move toward a more plural, realistic, and stigma-free representation of older adults in the media.

1. Introduction

Population ageing has become a defining demographic trend of contemporary societies, bringing with it important social and health challenges as well as new opportunities for building a more equitable and inclusive society.

According to data from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2024), by 2030, it is estimated that one in six people worldwide will be aged 60 years or older, reflecting a substantial demographic shift. By that time, the number of individuals in this age group will have increased significantly compared to 2020 levels. Projections indicate that by 2050, the number of individuals aged 60 and over will double, reaching 2.1 billion. Furthermore, the population aged 80 years and older is anticipated to triple between 2020 and 2050, rising to approximately 426 million.

In Western contexts, older adults frequently encounter negative social perceptions related to ageing. While historically and culturally older individuals were viewed as sources of wisdom, authority, and family cohesion, contemporary representations predominantly associate them with dependency, fragility, uselessness, or slowness (Chulián et al., 2024). These collective imaginaries are reinforced by the prevailing cultural narratives of media, which emphasize youth, physical beauty, and productivity (Haboush et al., 2012; Loos & Ivan, 2018; Saucier, 2011).

Age discrimination, known as “ageism,” has become one of the most socially accepted and normalized forms of exclusion today, alongside racism and sexism (Phelan, 2018). As stated by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020), ageism negatively affects individuals’ health, functioning, and longevity, while also creating systemic barriers across sectors such as education, employment, health, and social care, leading to the marginalization of older adults by limiting their access to services and undervaluing their contributions.

In this regard, the portrayal of older adults in the media is particularly significant, given that media discourse shapes social perceptions, legitimizes specific narratives, and reinforces established stereotypes. Research has demonstrated that media tend to frame ageing negatively, focusing on illness, dependency, and economic or familial burden (Molina et al., 2023).

However, another relevant body of literature has highlighted the overrepresentation of the so-called “third age,” portraying older adults as healthy, active, and youthful retirees (Loos & Ivan, 2018; Xu, 2022). While such depictions may appear positive, they risk producing an idealized and unrealistic image of later life, which can obscure the diversity of ageing experiences and create new forms of social pressure. Thus, both negative stereotypes and excessively positive or homogenizing portrayals can contribute to distorted imaginaries of ageing, limiting the possibility of balanced and inclusive representations.

Despite the growing societal importance of this issue, academic interest in studying ageism in the media is relatively recent and systematic studies examining the media’s portrayal of older adults remain scarce. This study aims to address this gap by analyzing how older adults are represented in media and identifying discriminatory discourses directed at them.

Media play a decisive role in constructing social imaginaries regarding ageing. This viewpoint aligns with the theory of the social construction of reality, which argues that everyday life presents itself as a socially constructed reality interpreted by individuals who attribute subjective meaning to it as a coherent world (Berger & Luckmann, 1991). Media not only inform but also construct reality (Entman, 1993; Noelle-Neumann, 1984) and influences public opinions and attitudes (Lippmann, 2012; McQuail, 2010; Wolf, 1994). Thus, media shape our perception of the world and engage audiences in the interpretative frameworks constructed through their discourse.

According to agenda-setting and framing theories, media establish interpretative frameworks for events and set priority issues for the public agenda. Issues that receive greater media coverage garner higher public interest, and the approach taken implicitly directs audiences toward specific ways of thinking about them (Entman, 1993; McCombs, 2006).

Various studies have shown the limited visibility of older adults in media, as their representation does not correspond to their demographic weight (Allen et al., 2023; Aznar & Suay, 2020; Oostlander et al., 2022). When older adults do appear, they are often depicted through paternalistic or compassionate lenses, employing negative stereotypical messages portraying them as a homogeneous group of dependent, vulnerable, and passive individuals (Phelan, 2018; Reuben, 2021; Amundsen, 2022). This phenomenon is particularly pronounced for older women and vulnerable subgroups within this demographic, who face compounded invisibility and discrimination (Edström, 2018; Molina et al., 2023). Such portrayals overlook the group’s heterogeneity, which includes active, autonomous, socially engaged individuals with valuable community contributions.

The impact of these representations is twofold. First, they shape societal perceptions, legitimizing discriminatory attitudes toward older adults. Second, they affect older adults’ self-perception, leading them to internalize negative images of themselves, thus limiting their active participation in social, economic, and cultural spheres (Sánchez et al., 2022). As reported by the United Nations, underrepresentation or biased representation in media directly impacts the self-esteem, health, and well-being of older adults (OPS, 2021).

Consequently, it is urgent to review and reformulate media approaches to ageing. Content should reflect the realities and contributions of all age groups, including older adults, fostering a more equitable and inclusive society (CEPSIGER, 2004). The World Health Organization itself, through its global campaign against age discrimination, has recognized the significant role media play and has proposed measures to ensure balanced representations of ageing (WHO, 2020).

Media determine which issues and groups are visible in society and shape how they are perceived, granting them immense power to transform social perceptions of ageing and to demonstrate that this life stage entails not only losses and risks but also compensations and achievements (Díaz, 2013, p. 491). As with issues such as racism and gender-based violence, media bear the responsibility of avoiding stereotype perpetuation and promoting older adults’ visibility and recognition as full-rights individuals.

Appropriate media coverage of this demographic can help combat ageism. To facilitate such coverage, various organizations have produced guidelines for journalists and communicators, aimed at promoting fair, inclusive, and realistic representations of ageing. Examples include Mira a las Personas Mayores [Look at older adults] (EAPN, 2012), Policy Measures to Reduce Stereotypical Representations of Older People in Long-Term Care (Xu & Allen, 2021), Guía para los medios de comunicación sobre el tratamiento de la información y la imagen de las personas mayores y el envejecimiento [Guide for media on handling information and images of older adults and ageing] (SEGG, 2021), Guía para una comunicación libre de edadismo hacia las personas mayores [Guide for an ageism-free communication towards older adults] (Molina et al., 2023), and Shifting perspectives: addressing ageism in media narratives (Kajander et al., 2024).

Recommendations within these guides emphasize portraying the heterogeneity of ageing experiences, while avoiding stereotypes that depict older adults as passive, dependent, or unproductive, and acknowledging their diversity, autonomy, and societal contributions. They also stress the importance of preventing both negative and overly positive representations, particularly those that idealize ageing and erase its heterogeneity. This includes using respectful terms such as “older adults” rather than “elderly” or “grandparents,” avoiding imagery that reinforces stereotypes, and prioritizing photographs and narratives that capture older adults in diverse roles and contexts. Furthermore, including their voices directly in media narratives is essential to ensuring their visibility.

Given the magnitude of ageism and its impact on social perceptions and older adults’ well-being, conducting a systematic review to identify, describe, and synthesize existing scientific evidence regarding media content’s role in reinforcing or preventing this discrimination is justified. This review will strengthen theoretical and empirical foundations and provide practical guidance for journalists, communicators, and policymakers to promote fairer, more inclusive, and realistic media treatment of older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

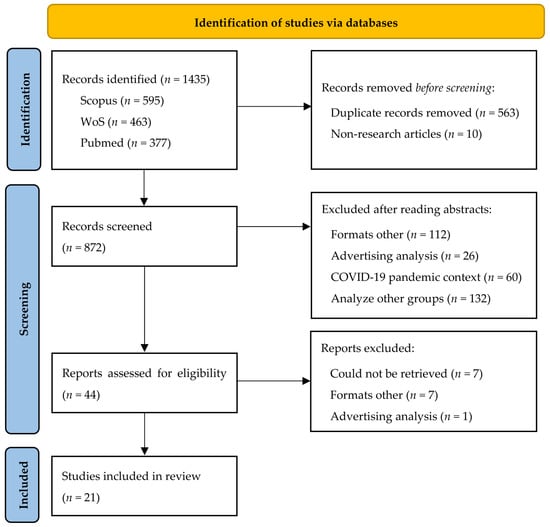

A systematic literature review was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. The flow diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the article selection process. The research question posed was: How are older adults represented in the media, and how do these representations contribute to either reinforcing or combating ageism, according to the existing scientific evidence? From this question, the following sub-questions were derived:

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

- What journalistic genres are used in media coverage of older adults, and how might these influence their representation?

- To what extent are older adults included as direct sources of information in journalistic content?

- What media framings prevail in the representation of older adults?

- What type of language do the media use when referring to older adults, and how does it contribute to reinforcing or combating ageist stereotypes?

- How are older adults visually represented in the media?

- What guidelines, strategies, or recommendations have been identified to promote respectful and non-ageist media portrayals of older adults?

Structured searches were conducted in three databases recognized for their relevance in Social Sciences and Communication: Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and PubMed, the latter included to capture interdisciplinary studies with public health, gerontology, or social psychology approaches addressing media representations of ageing. The search strategy balanced sensitivity (capturing the maximum relevant articles) and specificity (excluding irrelevant literature), using Boolean operators and terms in English and Spanish.

To conduct the literature search, a strategy was developed by grouping terms into three thematic axes: older adults, media, and ageism (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search strings for treatment of older adults in the media.

The searches were conducted independently by two researchers on 4 July 2025. No restrictions were applied regarding language or publication date, aiming to access all available literature and trace developments over time.

To ensure the quality and relevance of the results, searches were limited to peer-reviewed academic articles, excluding books, chapters, theses, and other non-peer-reviewed documents, using specific document-type filters available in each database.

A total of 1435 results were obtained: 595 from Scopus, 463 from WoS, and 377 from PubMed. Of these, duplicates (563) and non-research articles (10) were removed. The two researchers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the remaining 862 results, resolving discrepancies by consensus.

To ensure conceptual consistency and methodological rigour, this review focuses exclusively on articles that analyze news media (press, radio, television, and their digital counterparts), while excluding other formats such as advertising, social media, cinema, comics, or other cultural industries. This decision rests primarily on a theoretical delimitation of the object of study to ageism in journalistic discourse, which is shaped by professional routines, editorial standards, verification practices, and gatekeeping logics that differ substantially from those governing other types of media formats.

Included articles addressed the media representation of older adults and met the following criteria: (a) they explicitly analyzed empirical mass media content such as print media, television, radio, and/or digital media; (b) they referred to phenomena such as ageism, age discrimination, or stereotypes associated with ageing; (c) they examined the role of media in shaping social perceptions.

Excluded were articles focusing on older adults’ representations in: (a) formats other than print media, television, radio, and/or digital media, such as social media, television fiction, or cinema; (b) advertising content analysis; and (c) those exclusively addressing the COVID-19 pandemic context. Studies were also excluded if they (d) focused on specific groups rather than older adults in general, and (e) addressed social perceptions, public policies, or other discourses on ageing without explicitly considering media as the object of study and/or without analyzing its content, including purely theoretical contributions.

44 articles remained, of which 7 could not be retrieved. After examining the full texts of the 37 retrieved articles, 16 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria, resulting in 21 articles included in this systematic review (Table 2).

Table 2.

Articles included in the review.

The analysis parameters for the selected documents are presented in Table 3, which represents the form systematically applied to each article.

Table 3.

Analysis variables.

3. Results and Discussion

A comprehensive overview of the studies included in the review is provided in Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

The 21 selected studies were published between 2006 and 2025, with a clear increase in the last three years (five in 2024 and two in 2025). This rise may be due to a growing academic interest in recent years in media representations of old age in contexts of societies with an increasing proportion of older populations.

All the studies are concentrated in just 12 countries. Canada ranks first (n = 7), followed by Ireland (n = 3) and Malaysia (n = 2). The rest of the studies are distributed among various European countries (Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, Poland, Ukraine), as well as in Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), the United States, and South America (Venezuela).

This concentration of research in Canada and Ireland could be related to their established academic traditions in gerontology and media studies, as well as to the fact that the issue of ageing occupies a prominent place in public debate in these countries.

The most commonly used methodological approaches are content analysis (n = 5) and critical discourse analysis (n = 5), often combined with framing or thematic analyses. Mixed qualitative approaches (discourse + thematic, comparative narrative; n = 4) are also present. The independent use of inductive thematic analysis is less frequent (n = 2).

The media analyzed are newspapers in the vast majority of studies (n = 20), although some articles also analyze other publications (n = 6). Only one study focused exclusively on television news programmes, and two analyzed only magazines.

The distribution of studies by area of knowledge shows a clear predominance of research situated within the social sciences, particularly sociology (n = 15). These studies typically adopt critical or interpretive approaches to the media representation of older adults, paying particular attention to discourses and social processes. Studies in the health sciences (n = 3) examine the implications of media portrayals for well-being and ageing-related care, and advocate for changes in language as well as greater awareness among professionals, including journalists and other stakeholders. Journalism studies (n = 3) focus on how the media construct and transmit narrative frames about old age and offer more explicit recommendations aimed at transforming news content.

All of the studies reviewed employ qualitative methodological approaches, and three of them combine these with quantitative approaches. The most commonly used method is critical discourse analysis (n = 10), which is combined in three cases with, respectively, inductive thematic analysis, comparative narrative analysis, and content analysis. The second most frequent method is content analysis (n = 6), combined in two cases with inductive thematic analysis. Discourse analysis (n = 2), inductive thematic analysis applied independently (n = 2), and critical framing analysis (n = 1) are also present.

The synthesis of the results revealed heterogeneity among the studies in terms of their objects of study, the time periods selected, and the variables analyzed.

The diversity in research objects reflects not only thematic breadth but also the various approaches to the phenomenon of ageing in the media. Some studies focus on the analysis of general media representations of older adults (Selvaraj & Sandaran, 2024; Yang et al., 2024), others address broader discourses related to concepts such as productive ageing or loneliness in old age (Rudman & Molke, 2009; Uotila et al., 2010), and some examine specific topics such as sexuality in later life (Wada et al., 2015) or the use of assistive devices (Fraser et al., 2016).

With regard to the time periods analyzed, some articles focus on short intervals of four weeks (n = 2), while others examine periods of one year (n = 3). There are articles that analyze periods ranging from one and a half to three years (n = 6), from four to six years (n = 6), and from ten to eleven years (n = 3). Another study examines the evolution of the media representation of old age over two decades (n = 1).

This temporal diversity has direct implications for the results and approaches of the studies. Those covering extended periods of media coverage provide perspective for detecting changes in narratives and the emergence of new discursive frameworks in the media representation of older adults. This is the case of Van Leeuwen et al. (2024), who assess the representation of older adults and their level of agency in 20 years in the Netherlands and Flanders over a span of 20 years. On the other hand, studies focusing on a single media event, such as Fealy et al. (2012), which analyzes the coverage in Ireland of the proposed legislation to reduce welfare provision for older adults, offer detailed analyses of specific social phenomena and reflect the media climate of a particular moment.

Regarding the variables analyzed, a wide methodological heterogeneity is also evident. Some studies prioritize the identification of discursive categories, such as dominant themes or frames, or the social roles attributed to older people (Rozanova et al., 2016; Fealy et al., 2012). Other works focus on variables such as the visibility and frequency of older adults’ appearances in the media, or the tones and values associated with these representations (Lepianka, 2015; Martin et al., 2009). There are also studies that employ more complex variables related to social processes, such as the marketization or familization of ageing, or to the construction of loneliness and support networks in old age (Wilińska & Cedersund, 2010; Uotila et al., 2010). This variety reflects, on the one hand, the multidimensional complexity of social representations of old age and, on the other, the different theoretical interests present in the literature reviewed.

Drawing on the data extracted from 21 empirical studies, we organize our findings around the central research question: “How do news media represent older adults, and in what ways do these representations reinforce or counter ageism?”, and its six subquestions.

3.1. Identified Journalistic Genres

Only 7 of the 21 studies explicitly included an analysis of the types of journalistic texts. In two of these (Fraser et al., 2016; Marier & Revelli, 2017), the journalistic genre is considered as a variable for analysis, but no specific results or conclusions are drawn about this variable. For their part, Rozanova et al. (2016) do not explicitly analyze genres; they focus only on news stories about older adults that appear on the front page, considering their relevance for visibility and public perception solely because they appear on the front page.

The 7 studies agree that most of the texts published in the media about older adults are news reports or straight news. In most of these studies, it is mentioned that “few opinion pieces,” “columns and letters,” or “feature articles” appear very infrequently.

The scientific literature indicates that purely informational genres tend to address facts superficially, without providing as much depth or explanation as interpretative or opinion texts can offer. In contrast, narrative-formatted stories produce more compassion toward the individuals in the story, more favourable attitudes toward the group, more beneficial behavioural intentions, and more information-seeking behaviour. Narrative news stories produced changes in emotions, attitudes, intentions, and behaviour that were beneficial to members of stigmatized groups (Oliver et al., 2012).

Specialized journalists also emphasize that, to improve coverage of topics related to older adults, a more nuanced and informed approach is advisable, one that goes beyond mere reporting (Senz, 2022). It is necessary to publish interviews with multiple voices, in-depth reports, and human-interest stories.

One of the studies evaluated in this review clearly highlights the importance of text types when addressing issues related to ageing, stating that “it is not the same to be the focal point of a short agency news item and an extended feature article” (Lepianka, 2015).

3.2. Older Adults as Sources of Information

In seven of the articles, it is not explicitly evaluated whether older adults appear as sources of information. In the remainder, it is observed that their presence as direct sources is very limited or simply non-existent, which demonstrates the scarce representation of older adults in the media analyzed. It is common for other people to speak about them in the third person, rather than for the media to give them a direct voice.

Rudman and Molke (2009) provide some examples where “some older adults are quoted as personal exemplars,” but this does not become a common practice. This suggests that, although occasional testimonies from older adults are sometimes included, it is neither a systematic nor a predominant resource in media coverage. On the other hand, Rozanova (2010) notes that “most articles explicitly drew upon individual experiences of older adults,” thus incorporating direct voices from this age group. However, even in this case, the author warns that representation may be mediated by a normative focus, centred on stories of success and overcoming adversity, rather than on the diversity of possible experiences.

Moreover, when older adults do appear as information sources, most often they provide their testimonies and life experiences, rather than serving as expert or institutional sources contributing their knowledge (Fraser et al., 2016).

As a consequence, older adults are underrepresented in the media and tend to be portrayed more as objects of discourse than as active subjects participating in the construction of news.

Manjarrés (2024) is the only author who analyzes the gender of older adults who appear in the news. His data indicate that the vast majority of voices represented in the media belong to men, which suggests that women are even more invisible within a group that is already discriminated against. Yang et al. (2024) indicate that newspapers do not feature voices of older adults who are already more marginalized within their group, such as those in advanced old age and those with more severe health problems, mental illness, financial difficulties, etc.

These results are consistent with scientific evidence, which shows that the most marginalized groups in society are also the most invisible in the media (Edström, 2018; Hurd et al., 2020; WHO, 2020).

This low presence of minority groups in particular, and older adults in general, as direct sources of information indicates that the media perpetuate their discrimination and stigmatization, rather than fostering their active participation in social debate.

3.3. Narrative Framing of Older Adults

The papers analyzed show a diversity of narrative approaches, although most refer to negative representations of old age, conveying images of older adults as a social and economic burden; as vulnerable and weak individuals, identified with illness; and as passive and dependent people who do not contribute to society. Media coverage mostly does not contain a positive or hopeful narrative, and general framing is negative or patronizing, lacking empowerment (Van Leeuwen et al., 2024).

The framing of older adults as a “social burden” (Martin et al., 2009) presents them through narratives of demographic crisis, economic dependency, and fragility, especially through discourses on the sustainability of public systems. This framing reinforces negative and utilitarian views of old age, in line with what Wilińska and Cedersund (2010) indicate, introducing the idea of “familization” and “marketization”; that is, the media portray older adults as dependent on the family or the market rather than as autonomous citizens. This framework emphasizes the transfer of responsibilities from the state to the private and commercial spheres.

Another common frame is that of individual responsibility, which reinforces the idea that well-being in old age depends mainly on personal choices and efforts, downplaying structural determinants and the role of public policies. The study by Rudman and Molke (2009) highlights the narrative of “productive aging,” which emphasizes that older adults must continue to be productive, active, and responsible for their own well-being, thus shifting attention away from structural or social conditions. Rozanova (2010) insists on the concept that “successful ageing is a personal choice.” The media discourse presents success in old age as the direct result of individual decisions and attitudes, making inequalities and social contexts invisible.

The articles analyzed also indicate that the media often consider older adults as a homogeneous group, overlooking the diversity of characteristics within the collective. It is also common for the media to normalize old age, pointing out “desirable” or “acceptable” models of ageing, which can be exclusionary for those who do not fit those patterns.

In Rozanova et al. (2006), it is highlighted that the media present a “diversity of older people,” showing older adults in various roles, from active consumers and caregivers to care recipients or subjects of “successful aging.” However, even within this supposed diversity, the study points out that normative models of what old age should be like tend to prevail.

On the other hand, Uotila et al. (2010) highlight the presence of positive framings of older adults, mainly referring to those in the “third age” rather than the “fourth.” This is related to the idea that within the group of older adults, the oldest are represented more negatively than the younger ones.

These findings align with previous international reviews on media ageism (Appel & Weber, 2017; Bai, 2014; Loos & Ivan, 2018), which also reported a predominance of negative framing and underrepresentation of older adults. This ageism has significant consequences, as it influences our everyday perceptions and interactions, including the way we relate to older adults and the way we see ourselves as we grow older (OPS, 2021).

3.4. Language Used to Refer to Older Adults

The reviewed studies show how the language used by the media reinforces ageist narratives and contributes to reproducing stereotypes and social representations of older adults in the media.

Rozanova et al. (2006) highlight the use of expressions such as “doddering old women” or “retirees,” which convey a stereotyped and homogeneous image of old age. This language, loaded with negative connotations, facilitates the construction of prejudice and the symbolic marginalization of older adults in society.

Martin et al. (2009) show the use of explicitly ageist terms such as “wrinklies,” “crumblies,” “pensioners” and “the elderly.” These appellations not only depersonalize but also reinforce a deficit-based and passive vision of older adults, anchored in physical deterioration and dependence.

In Rozanova (2010), media discourse systematically highlights values such as success, youth, and physical activity. The use of these terms not only establishes a normative ideal of old age but can also contribute to the symbolic exclusion of those who do not fit that profile.

Wilińska and Cedersund (2010) conduct a detailed analysis of the metaphors and terms used to talk about old age and care. Although their study acknowledges a wide variety of expressions, many of them perpetuate the idea of dependence, vulnerability, and loss of autonomy.

On the other hand, Rudman and Molke (2009) identify a tendency to associate positive adjectives with youth, such as “fit,” “tan,” “active,” which implies that desirable qualities in old age are those that emulate youth. Thus, the discourse not only idealizes youth but also makes invisible the diversity of life experiences in old age.

Three of the articles reviewed do not make explicit references to the use of language to refer to older adults.

The literature reveals that language and terminology are key factors for media destigmatization, together with framing, education, and contact (Kunze, 2024). Inclusive and stigma-free language is essential to reduce social prejudice and promote equality among people; therefore, by carefully choosing the terms employed, the media can also contribute to the destigmatization of discriminated groups in society (Clement et al., 2013).

3.5. Images of Older Adults

Only one of the articles (Manjarrés, 2024) analyzes the photographs that illustrate news stories about older adults. His research shows that none of the images features a single person; instead, all of them depict groups of people. It is also evident that many published images reinforce the narrative of the physical frailty of older adults, as weakened body parts (without faces), walking sticks, prostheses, or images showing reduced mobility are highly visible.

Furthermore, this study concludes that newspaper images do not show women in leadership positions, as in all the photographs where a figure appears with a megaphone or microphone, the main character is a man.

These results are consistent with scientific evidence, which finds that older adults are visually underrepresented in the media, and when they do appear, they are more likely to be represented negatively, as dependent and disconnected from the rest of the world. Although most are actively involved in their communities, the images mostly show them as passive individuals, and they are rarely shown with technology or in work environments (Thayer & Skufca, 2020).

Images of old age and ageing in the media are of great importance as they have a significant influence on society’s perceptions and expectations of old age (Wangler & Jansky, 2023). Visual ageism refers to depicting older adults in minor, unrealistic, or negative roles in images, lacking positive qualities. These portrayals can be harmful, shaping negative attitudes toward ageing in individuals and policymakers (Ivan et al., 2020).

The studies evaluated in this review on the representation of older adults in the media have focused mainly on written content, leaving aside the important visual component. This represents a significant limitation, since images (photographs, illustrations, infographics) play a fundamental role in the construction of stereotypes and in the social perception of old age.

Given that images have rarely been considered in the reviewed studies, the possibility is lost to analyze key issues such as the types of older adults depicted (active, dependent, diverse), the context of the photographs, the framing, or the presence of symbolic elements that can reinforce or challenge ageist discourses.

3.6. Recommendations to Combat Ageism in the Media

In 14 of the articles evaluated, there are no explicit recommendations directed at the media to help them avoid ageism in their content. The general trend is to point out recommendations indirectly or theoretically, rather than offering clear guidelines for improving media coverage of older adults. Therefore, there is mainly a descriptive or analytical approach, without these analyses being translated into practical proposals to improve the information published by the media.

Although most studies do not make recommendations, their analyses provide a solid starting point to guide editorial policies and journalistic practices. Almost all studies emphasize the importance of reviewing the discourses and stereotypes present in media coverage and the desirability of including the voices of older adults in the media so they can participate in public debates.

Among the articles that do make explicit recommendations, the most commonly mentioned proposals are to use more careful and respectful language to avoid homogeneity and discriminatory or ageist phrases; to increase the direct representation of older adults by including more diverse voices and opinions; to present a positive and diverse image of ageing; and to reflect the contribution of older adults to the growth and enrichment of society.

Additionally, three studies (Fealy et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2024; Selvaraj & Sandaran, 2024) highlight the need for collaboration between journalists and other stakeholders, such as economists, politicians, educators, and health professionals, to eliminate negative stereotypes and prejudices about ageing in the media.

For their part, Fealy et al. (2012) propose fostering deeper coverage and analysis of the real problems affecting older adults, emphasizing the importance of the type of text used when addressing this group.

The evidence highlights the lack of newsroom training to address stories about older adults without reproducing ageist biases, which is why specific training for journalists is needed (Allen et al., 2023; Copp et al., 2022). Professional programs such as Journalists in Aging Fellows1, Age Boom Academy2 or the European Journalism Training Association (EJTA) initiative3 demonstrate that better-trained journalists produce more plural and inclusive narratives.

4. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the relevance of thoroughly analyzing the media representation of older adults, given the fundamental role that the media play in the social construction of old age and in the perpetuation or transformation of ageist stereotypes.

The media select and emphasize certain age aspects, so they play a decisive role when it comes to shaping and staging images of ageing. Journalistic content about old age and ageing is especially important in countries undergoing major demographic change, as these portrayals play a key role in shaping social discussions on how to address ageing, intergenerational relationships, and the welfare state (Wangler & Jansky, 2023).

By comparatively examining recent international studies, this work helps to identify methodological and disciplinary gaps in the existing literature. Its contribution points to the need for interdisciplinary approaches that integrate both sociological and communicative perspectives in order to advance toward more equitable media coverage of ageing.

Twenty-one articles have been analyzed with the aim of discovering how the media represent older adults and how these representations contribute to reinforcing or combating ageism, according to the existing scientific evidence.

It is important to emphasize the limited presence of research from Europe, South America, and Asia, which represents a significant limitation in terms of geographical diversity. This gap hinders meaningful comparisons between different media and cultural contexts and constrains the extent to which the findings of this review can be extrapolated beyond the predominantly represented settings.

On the other hand, it should be noted as a limitation that most of the studies included focus exclusively on print media, primarily newspapers and magazines. This concentration may lead to the omission of perspectives and forms of representation found in other media formats, especially television and radio, and may hinder a broader and more nuanced understanding of how ageing is addressed across the current media landscape.

Information sources have not been explicitly analyzed in any of the reviewed articles. Even so, more than half of them have found the scarce presence of older adults as active subjects in the news. Except for occasional exceptions, the voices of older adults themselves are rarely included, which contributes to their depersonalization and to the perpetuation of negative stereotypes about old age.

Instead of giving a direct voice to older adults, others speak about them, which reinforces cultural ageism and discrimination on the basis of age. By not appearing on the media agenda, their needs and opinions become invisible to the rest of society and to policymakers, making it difficult to create inclusive public policies tailored to this group.

Moreover, if the plurality of experiences and roles of older adults in society is not reflected, the media limit the creation of positive role models and contribute to homogenizing old age as a passive stage, without protagonism or valuable contributions.

The predominant narrative approach in the reviewed articles also contributes to reproducing normative and stigmatizing frames. It is noted that diversity among older adults is occasionally reflected, but it is more common to find narratives that present them as a social and economic burden, as a homogeneous group, and as vulnerable and weak individuals who do not contribute to society.

Another notable trend is the focus on a specific model of “successful aging” based on personal choice, which tends to individualize responsibility for the way one ages. This narrative overlooks the structural causes of ageing, such as social policies or economic inequalities, perpetuating partial and biased views.

Regarding the language used, there is a predominance of ageist terms and expressions, both explicitly and in more subtle forms of normalization and exclusion. Also noteworthy is the exaltation of values associated with youth and physical activity as the only way to achieve an “acceptable” old age.

Normative and stigmatizing language limits the plurality of possible images and consolidates exclusionary discourses, because words not only reflect but also create reality. The terms chosen construct the image of old age that the media transmit to society: if the media insist on negative words, they build an image of old age as problematic or passive. If they use respectful and precise language, they promote inclusion and plurality.

The results of this systematic review highlight the need to move toward more plural and inclusive media coverage that reflects older adults in a way that is more faithful to reality, more respectful, and without stigmatizing them. It is essential for the media to incorporate the active voices of this group and to review the narrative frames and language used.

A relevant finding of this review is that most of the studies analyzed come from the field of sociology, while research developed from the fields of communication and journalism is very scarce. This disciplinary imbalance limits the analysis of fundamental aspects related to professional routines and journalistic production processes, which may play a key role in the reproduction or reinforcement of ageist discourses in the media.

The limited presence of research from the academic field of journalism restricts the analysis of information practices, editorial criteria, and the internal dynamics of newsrooms. This makes it difficult to understand how these factors influence the construction of stereotypes about older adults in news coverage.

This disciplinary limitation is reflected in the fact that the reviewed articles do not explicitly analyze the type of information sources used in the news, nor do they analyze journalistic genres or images.

Information sources determine which voices and perspectives are included or excluded in the news. If they are not studied, it is not possible to know whether older adults actively participate as sources, whether they are consulted only as passive witnesses, or whether institutional or expert voices predominate and speak on their behalf. This directly affects the plurality and legitimacy of the information.

It is also important to analyze journalistic genres, because each one has its own narrative logic, objectives, and ways of constructing reality. If the different genres are not distinguished, the ability to identify how the treatment of older adults varies according to the type of text is lost, which can hide specific ageist discursive practices or, conversely, examples of good practices.

As for images, it is evident that they not only illustrate but also convey messages, reinforce stereotypes, or can help to humanize older adults. Ignoring iconographic analysis makes it impossible to assess whether photographs perpetuate clichés of dependency, loneliness, and frailty, or whether they present older adults as positive and diverse, reflecting a variety of activities and active participation in society.

Without these analyses, it is difficult to propose practical and specific recommendations to combat ageism in journalistic work. In fact, another conclusion of this review is that most of the studies analyzed rarely include explicit recommendations aimed at journalists to avoid ageism in professional practice, or else these recommendations are generic or underdeveloped.

This may also be related to the fact that most of the research comes from the field of sociology and predominantly uses methodologies focused on discourse analysis. As a result, the contributions of the studies tend to be mainly theoretical and reflective, with little practical guidance for transforming journalistic routines or promoting journalism free from ageism.

This limitation highlights the need for future research to move toward operational and applicable proposals that facilitate the work of communication professionals in building fairer and more inclusive representations of older adults.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/journalmedia6030150/s1, Table S1: Summary of the reviewed studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.C.-M.; methodology, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; software, I.C.-M.; validation, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; formal analysis, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; investigation, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; resources, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; data curation, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, I.C.-M.; writing—review and editing, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; visualization, I.C.-M. and M.-T.S.-D.; supervision, I.C.-M.; project administration, I.C.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | https://www.geron.org/Resources/Journalists-in-Aging-Fellows-Program (accessed on 18 July 2025). |

| 2 | https://ageboom.columbia.edu/ (accessed on 18 July 2025). |

| 3 | https://ejta.eu/index.php/2023/11/01/task-force-how-to-teach-inclusive-journalism/ (accessed on 18 July 2025). |

References

- Allen, L. D., Bradley, D. B., & Ayalon, L. (2023). What’s keeping residents “out of the mainstream”: Challenges to participation in the news media for older people living in residential care. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 42(6), 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, D. (2022). A critical gerontological framing analysis of persistent ageism in NZ online news media: Don’t call us “elderly”! Journal of Aging Studies, 61, 101009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, M., & Weber, S. (2017). Do mass mediated stereotypes harm members of negatively stereotyped groups? A meta-analytical review on media-generated stereotype threat and stereotype lift. Communication Research, 48(2), 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, H., & Suay, A. (2020). Treatment and participation of older people in mass media: Qualified opinion of specialized journalists. Profesional de la Información, 29(3), e290332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X. (2014). Images of ageing in society: A literature review. Population Ageing, 7, 231–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandina, N., Pankevych, O., Liubarets, V., Vyshnevska, Y., & Rodinova, N. (2023). Gerontological ageism as a social challenge and its detection in Ukrainian news media content. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 81, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1991). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- CEPSIGER—Centro de Psicología Gerontológica. (2004). Periodismo y comunicación para todas las edades. Ministerio de Comunicaciones de Bogotá. Available online: https://www.gerontologia.org/portal/archivosUpload/PeriodismoComunicacionParaTodasLasEdades.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Chulián, A., Valdivia, S., & Páez, M. (2024). Una mirada contextual al edadismo. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 50(182), 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S., Lassman, F., Barley, E., Evans-Lacko, S., Williams, P., Yamaguchi, S., Slade, M., Rüsch, N., & Thornicroft, G. (2013). Mass media interventions for reducing mental health-related stigma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2013(7), CD009453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, T., Dakin, T., Nickel, B., Albarqouni, L., Mannix, L., McCaffery, K. J., Barratt, A., & Moynihan, R. (2022). Interventions to improve media coverage of medical research: A codesigned feasibility and acceptability study with Australian journalists. BMJ Open, 12(6), e062706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, L. (2013). La imagen de las personas mayores en los medios de comunicación. Sociedad y Utopía. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 41, 483–502. Available online: http://www.acpgerontologia.com/documentacion/imagendiazaledo.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Dunsmore, R. A., Funk, L., & Sawchuk, D. (2025, May 3). Social identity and power: Older adults as “care recipients” in media content on family care. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EAPN—The European Anti-Poverty Network. (2012). Mira a las personas mayores: Guía de estilo para periodistas sobre personas mayores. Available online: https://www.eapn.es/ARCHIVO/documentos/documentos/GuiaEstilo_PeriodistasyMayores.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Edström, M. (2018). Stereotypes of ageing in intergenerational talk and in media representations. Feminist Media Studies, 18(1), 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fealy, G., Di Placido, M., O’Donnell, D., Drennan, J., Timmins, F., Barnard, M., Blake, C., Connolly, M., Donnelly, S., Doyle, G., Fitzgerald, K., Frawley, T., Gallagher, P., Guerin, S., Mangiarotti, E., McNulty, J., Mucheru, D., O’Neill, D., Segurado, R., … Čartolovni, A. (2024). ‘Ageing well’: Discursive constructions of ageing and health in the public reach of a national longitudinal study on ageing. Social Science & Medicine, 341, 116518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fealy, G., McNamara, M., Treacy, M. P., & Lyons, I. (2012). Constructing ageing and age identities: A case study of newspaper discourses. Ageing and Society, 32(1), 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, S. A., Kenyon, V., Lagacé, M., Wittich, W., & Southall, K. E. (2016). Stereotypes associated with age-related conditions and assistive device use in canadian media. The Gerontologist, 56(6), 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboush, A., Warren, C. S., & Benuto, L. (2012). Beauty, ethnicity, and age: Does internalization of mainstream media ideals influence attitudes towards older adults? Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 66(9–10), 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, L., Mahal, R., Ng, S., & Kanagasingam, D. (2020). From invisible to extraordinary: Representations of older LGBTQ persons in Canadian print and online news media. Journal of Aging Studies, 55, 10087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M. A. (2023). Redefining older Australians: Moving beyond stereotypes and consumer narratives in print media representations. Media International Australia, 194(1), 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivan, L., Loos, E., & Tudorie, G. (2020). Mitigating visual ageism in digital media: Designing for dynamic diversity to enhance communication rights for senior citizens. Societies, 10(4), 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajander, N., Meyer, F., Pasztor, Z., & Seiger, F. (2024). Shifting perspectives: Addressing ageism in media narratives. European Commission, Ispra, JRC138090. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC138090/JRC138090_01.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Kunze, D. (2024). Systematizing destigmatization in the context of media and communication: A systematic literature review. Frontiers in Communication, 9, 1331139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepianka, D. (2015). How similar, how different? On Dutch media depictions of older and younger people. Ageing and Society, 35(5), 1095–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, W. (2012). Public opinion. Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Loos, E., & Ivan, L. (2018). Visual ageism in the media. In L. Ayalon, & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 163–176). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjarrés, E. (2024). Análisis de narrativas periodísticas sobre protestas de personas mayores en Venezuela. European Public & Social Innovation Review, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marier, P., & Revelli, M. (2017). Compassionate Canadians and conflictual Americans? Portrayals of ageism in liberal and conservative media. Ageing and Society, 37(8), 1632–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R., Williams, C., & O’Neill, D. (2009). Retrospective analysis of attitudes to ageing in the Economist: Apocalyptic demography for opinion formers. BMJ, 339, b4914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. (2006). Estableciendo la agenda: El impacto de los medios en la opinión pública y en el conocimiento. Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail’s mass communication theory. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, E., Ramos, I., & Fernández, A. B. (2023). Guía para una comunicación libre de edadismo hacia las personas mayores. Fundación HelpAge International España. Available online: https://www.helpage.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/GUIA-PARA-UNA-COMUNICACION-LIBRE-DE-EDADISMO-HACIA-LAS-PERSONAS-MAYORES-1.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Noelle-Neumann, E. (1984). The spiral of silence: Public opinion-our social skin. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M. B., Dillard, J. P., Bae, K., & Tamul, D. J. (2012). The effect of narrative news format on empathy for stigmatized groups. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 89(2), 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostlander, S. A., Champagne-Poirier, O., & O’Sullivan, T. L. (2022). Media portrayal of older adults across five Canadian disasters. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 94(2), 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OPS—Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (2021). Informe mundial sobre el edadismo. OPS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, A. (2018). Researching Ageism through Discourse. In L. Ayalon, & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 549–564). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, N. (2021). Societal age stereotypes in the U.S. and U.K. from a media database of 1.1 billion words. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova, J. (2010). Discourse of successful aging in The Globe & Mail: Insights from critical gerontology. Journal of Aging Studies, 24(4), 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova, J., Miller, E. A., & Wetle, T. (2016). Depictions of nursing home residents in US newspapers: Successful ageing versus frailty. Ageing & Society, 36(1), 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova, J., Northcott, H. C., & McDaniel, S. A. (2006). Seniors and Portrayals of Intra-generational and Inter-generational Inequality in the Globe and Mail. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 25(4), 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, D. L., & Molke, D. (2009). Forever productive: The discursive shaping of later life workers in contemporary Canadian newspapers. Work, 32(4), 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucier, M. G. (2011). Midlife and beyond: Issues for aging women. Journal of Counseling & Development, 82(4), 387–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M., Autric, G., Fernandez, G., Rojo, F., Agulló, M. S., Sánchez, D., & Rodriguez, V. (2022). Social image of old age, gendered ageism and inclusive places: Older people in the media. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(24), 17031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SEGG—Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología. (2021). Guía para los medios de comunicación sobre el tratamiento de la información y la imagen de las personas mayores y el envejecimiento. Available online: https://www.segg.es/media/descargas/5GUIASEGGPARAMEDIOS.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Selvaraj, S., & Sandaran, S. C. (2024). Discourses of aging in a Malaysian online newspaper: Shaping of the perceptions of society. Research on Ageing and Social Policy, 12(2), 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senz, K. (2022, November 15). 6 tips for improving news coverage of older people. The Journalist’s Resource. Available online: https://journalistsresource.org/home/6-tips-for-improving-news-coverage-of-older-people/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Thayer, C., & Skufca, L. (2020). Media image landscape: Age representation in online images. Innovation in Aging, 4(S1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uotila, H., Lumme-Sandt, K., & Saarenheimo, M. (2010). Lonely older people as a problem in society—Construction in Finnish media. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 5(2), 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C., Jacobs, A., Mariën, I., & Vercruyssen, A. (2024). What do the papers say? The role of older adults in 20 years of digital inclusion debate in Dutch and Flemish newspapers. International Journal of Ageing and Later Life, 17(2), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, M., Hurd, L., & Rozanova, J. (2015). Constructions of sexuality in later life: Analyses of Canadian magazine and newspaper portrayals of online dating. Journal of Aging Studies, 32, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangler, J., & Jansky, M. (2023). Media portrayal of old age and its effects on attitudes in older people: Findings from a series of studies. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO—World Health Organization. (2020). Decade of healthy ageing: Plan of action. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/decade-of-healthy-ageing/decade-proposal-final-apr2020-en.pdf?sfvrsn=b4b75ebc_28 (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- WHO—World Health Organization. (2024). Ageing and health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Wilińska, M., & Cedersund, E. (2010). “Classic ageism” or “brutal economy”? Old age and older people in the Polish media. Journal of Aging Studies, 24(4), 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M. (1994). Los efectos sociales de los media. Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W. (2022). (Non-)Stereotypical representations of older people in Swedish authority-managed social media. Ageing and Society, 42(3), 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., & Allen, L. D. (2021). Policy measures to reduce stereotypical representations of older people in long-term care. Available online: https://euroageism.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Xu-Allen-2021-Policy-Brief-Stereotypical-Representations-of-Older-People-in-Long-Term-Care.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Yang, L. F., Fernandez, P. R., & Tan, L. P. G. (2024, July 22). A comparative study of multi-ethnic perspectives on aging in Malaysian newspapers. Journalism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).