Online Verbal Aggression on Social Media During Times of Political Turmoil: Discursive Patterns from Poland’s 2020 Protests and Election

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Online Aggression and Hostile Communication

2.2. Emotion-Driven Political Communication

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

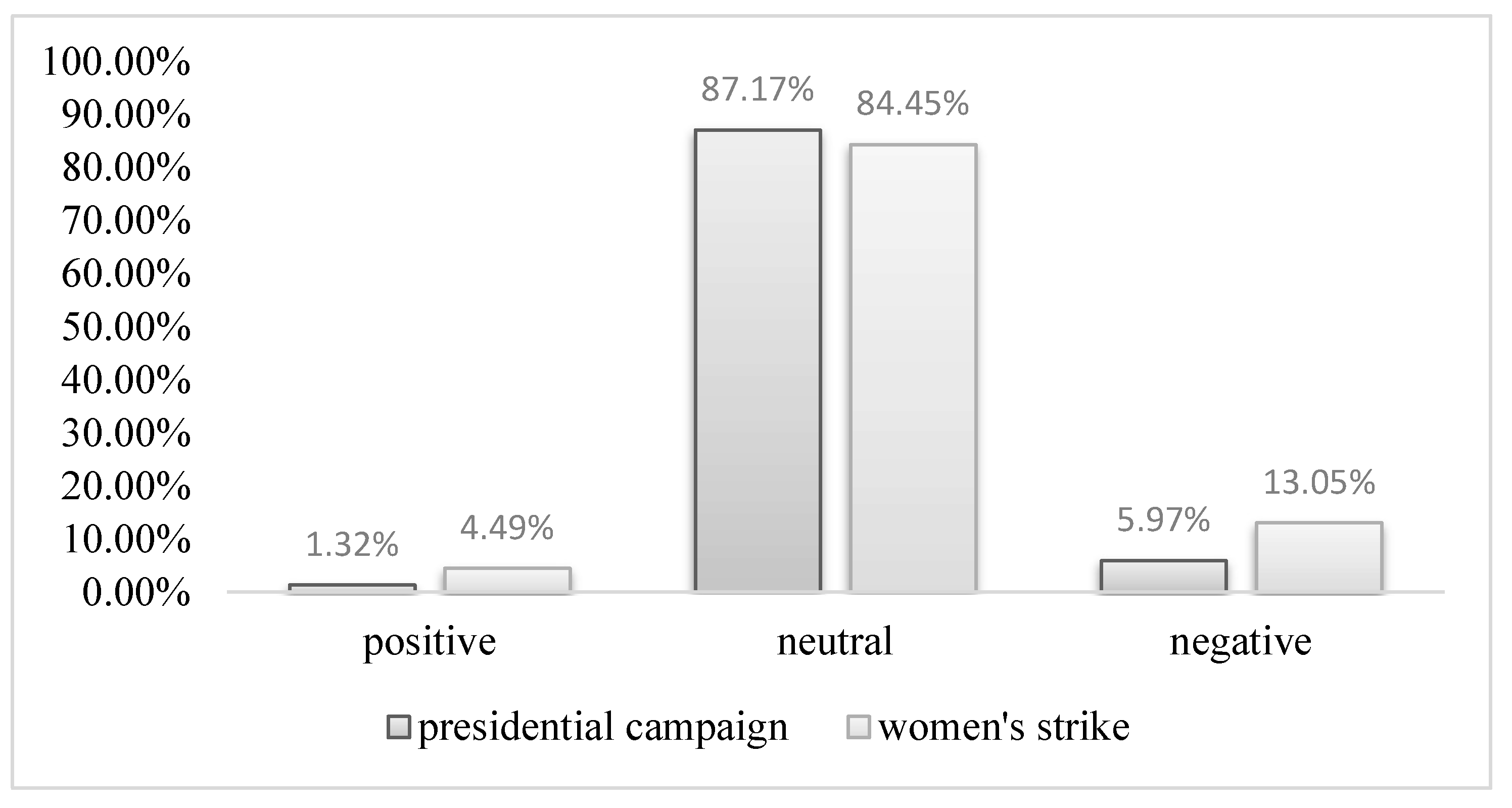

4.1. Sentiment Analysis

4.2. Aggression in Posts and Tweets

- Name-calling, i.e., the use of abusive language in references to politicians and political parties, in particular the incumbent president, the leading opposition candidate, and the ruling party:Sample post from 27 November 2020:Morally screwed up and spiritually stagnant dilettantes #poland #kaczyński #(…) #duda #morawiecki (…)

- Rude or disrespectful remarks directed at presidential candidates and political parties:Sample tweet from 7 July 2020:After bringing the @presidentpl office down to the level of @USAmbPoland, now this stupid candidate @AndrzejDuda who still holds this office brings it much lower, because down to the level of German newspapers and rags.Sample tweet from 16 July 2020:Keep inciting against @trzaskowski_—that will surely help you. After posts like this, I’ve had enough of you for the whole week!!!! Shall I remind you who made @AndrzejDuda what he is, who in 2015 was urging people to vote for him!!

(…) #PresidentofPolishAffairs #Story-teller2020 #RafałDon’tLie #Duda1round #LGBT #We’veHadEnough #Polandconnectsus

(…) #PresidentialDebate2020 #Story-teller2020 #RafałDon’tLie #RafałChicken #LGBT #We’veHadEnough #Polandconnectsus #Rafał’sSamba

When someone grabs you by your ankle, you say enough is enough. And when they grab your crotch, you scream #get the fuck out!. This is the language of a cornered woman #women’sstrike #SentenceOnWomen #women’sprotest #women’shell https://www.wysokieobcasy.pl/Instytut/7,163391,26444649,gdy-ktos-cie-lapie-za-kostke-mowisz-dosc-gdy-za-kolano.html?disableRedirects=true (accessed on 22 May 2021). The very problem of this protest could easily be solved. It would be enough to force men by law to tie the vas deferens. Then the one who would like to start a family…”.

I have not seen a greater social pathology than PiS. Lies plus propaganda and sewage. https://twitter.com/Link anonymised.

The church, as an institution, has blood on its hands and is co-responsible for the current protests. I am absolutely satisfied that the protests are so massive and reveal true emotions of society.#fuckoff #women’s protest #blackprotest #Women’sstrike #women’shell #abortionban https://twitter.com/Link anonymised.

A moment ago in Katowice (you can see it live on FB) the police used gas to attack peaceful demonstrators. There were children and elderly people in the crowd. It’s disgraceful behavior. I will demand an explanation from the police for this groundless aggression.

Let us prepare for the coming of the Messiah. #MidweekMegaWord #PiS #POLNED #Seym #Covid_19 #Women’sStrike #COVID19 #christmas #london #TheChase #PS5

Fuck it, Shit XDDDDDDDD https://Link anonymised.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The eight most popular presidential candidates, in the order of votes received in the first round of the 2020 presidential election, were Andrzej Duda, Rafał Trzaskowski, Szymon Hołownia, Krzysztof Bosak, Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, Robert Biedroń, Stanisław Żółtek, and Marek Jakubiak. |

References

- Albertson, B., & Gadarian, S. K. (2015). Anxious politics: Democratic citizenship in a threatening world. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aldamen, Y. (2023). Xenophobia and hate speech towards refugees on social media: Reinforcing causes, negative effects, defense and response mechanisms against that speech. Societies, 13, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Almahfali, M., & El-Husseini, R. (2023). Exploiting sociocultural issues in election campaign discourse: The case of Nyans in Sweden. Societies, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & McKenna, K. Y. A. (2006). The contact hypothesis reconsidered: Interacting via the internet. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11, 825–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypas, D., Preece, A., & Camacho-Collados, J. (2023). Negativity spreads faster: A large-scale multilingual twitter analysis on the role of sentiment in political communication. Online Social Networks and Media, 33, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouvier, G. (2020). Racist call-outs and cancel culture on twitter: The limitations of the platform’s ability to define issues of social justice. Discourse, Context & Media, 38, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Pulgarín, S. A., Suárez-Betancur, N., Vega, L. M. T., & López, H. M. H. (2021). Internet, social media and online hate speech. Systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 58, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampaglia, G. L., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2015). The production of information in the attention economy. Scientific Reports, 5, 9452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloudy, J., Gotlieb, M. R., & McLaughlin, B. (2024). Online political networks as fertile ground for extremism: The roles of group cohesion and perceived group threat. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 21, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. (1997). Recommendation No. R(97)20 of the committee of ministers to member states on “hate speech”. Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, C., Golder, M., Gschwend, T., & Indriđason, I. H. (2020). It is not only what you say, it is also how you say it: The strategic use of campaign sentiment. The Journal of Politics, 82, 1044–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-Ferdon, C., & Hertz, M. F. (2007). Electronic media, violence, and adolescents: An emerging public health problem. Journal of Adolescent Health, 41, S1–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domalewska, D., Gasztold, A., & Wrońska, A. (2025). Humans in the cyber loop: Perspectives on social cybersecurity. Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everton, S. F. (2016). Social networks and religious violence. Review of Religious Research, 58, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeibe, C. (2021). Hate speech and election violence in Nigeria. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H., Du, W., Dahou, A., Ewees, A. A., Yousri, D., Elaziz, M. A., Elsheikh, A. H., Abualigah, L., & Al-Qaness, M. A. A. (2021). Social media toxicity classification using deep learning: Real-world application UK Brexit. Electronics, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallacher, J. D., Heerdink, M. W., & Hewstone, M. (2021). Online engagement between opposing political protest groups via social media is linked to physical violence of offline encounters. Social Media and Society, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L. (2016). The emergence of the human flesh search engine and political protest in China: Exploring the internet and online collective action. Media, Culture & Society, 38, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstlé, J., & Nai, A. (2019). Negativity, emotionality and populist rhetoric in election campaigns worldwide, and their effects on media attention and electoral success. European Journal of Communication, 34, 410–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, S. (2015). Discursive strategies of blame avoidance in government: A framework for analysis. Discourse & Society, 26, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepp, A. (2019). Deep mediatization. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-06490-3. [Google Scholar]

- KhosraviNik, M., & Esposito, E. (2018). Online hate, digital discourse and critique: Exploring digitally-mediated discursive practices of gender-based hostility. Lodz Papers in Pragmatics, 14, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, U., Koc-Michalska, K., & Russmann, U. (2022). Are campaigns getting uglier, and who is to blame? Negativity, dramatization and populism on Facebook in the 2014 and 2019 EP election campaigns. Political Communication, 40, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyus, J. (2021). Inwektywa jest kobietą. Socjolingwistyczne determinanty inwektywizacji języka na przykładzie haseł protestowych ze Strajku Kobiet 2020. Językoznawstwo, 15, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsten, F. W. (2020). Historical prefigurations of vitriol. Communities, constituencies and plutocratic insurgency. In S. Polak, & D. Trottier (Eds.), Violence and trolling on social media. History, affect, and effects of online vitriol (pp. 88–108). Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuligowski, W. (2021). Język Niesłyszanych. In P. Kosiewski (Ed.), Język rewolucji (pp. 27–30). Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego. [Google Scholar]

- Mane, S. S., Kundu, S., & Sharma, R. (2025). A survey on online aggression: Content detection and behavioral analysis on social media. ACM Computing Surveys, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G. E., & MacKuen, M. B. (1993). Anxiety, enthusiasm, and the vote: The emotional underpinnings of learning and involvement during presidential campaigns. American Political Science Review, 87, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooijman, M., Hoover, J., Lin, Y., Ji, H., & Dehghani, M. (2018). Moralization in social networks and the emergence of violence during protests. Nature Human Behaviour, 2, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nai, A., Schemeil, Y., & Marie, J. (2017). Anxiety, sophistication, and resistance to persuasion: Evidence from a quasi-experimental survey on global climate change. Political Psychology, 38, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyazi, T. A., & Kuru, O. (2024). Motivated mobilization: The role of emotions in the processing of poll messages. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 29, 184–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepiak, E. (2020). White femininity and trolling. Historicizing some visual strategies of today’s far right. In S. Polak, & D. Trottier (Eds.), Violence and trolling on social media. History, affect, and effects of online vitriol (pp. 109–130). Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Polak, S., & Trottier, D. (2020). Introducing online vitriol. In Violence and trolling on social media. History, affect, and efffects on online vitriol (pp. 9–24). Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rathje, S., Van Bavel, J. J., & van der Linden, S. (2021). Out-group animosity drives engagement on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118, e2024292118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ibanez, M., Gimeno-Blanes, F. J., Cuenca-Jimenez, P. M., Soguero-Ruiz, C., & Rojo-Alvarez, J. L. (2021). Sentiment analysis of political tweets from the 2019 Spanish elections. IEEE Access, 9, 101847–101862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, H., Leuschner, V., Böckler, N., Akhgar, B., & Nitsch, H. (2018). Developmental pathways towards violent left-, right-wing, Islamist extremism and radicalization. International Journal of Developmental Science, 12(1–2), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T., Tao, X., Dann, C., Xie, H., Li, Y., & Galligan, L. (2023). Sentiment analysis and opinion mining on educational data: A survey. Natural Language Processing Journal, 2, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somer, M., & McCoy, J. (2018). Transformations through polarizations and global threats to democracy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak-Jazurkiewicz, E. (2021). The change of the media system as the goal of the media policy of the Law and Justice (PiS) government from 2015. Przegląd Europejski, 4, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, S., Bleier, A., Lietz, H., & Strohmaier, M. (2018). Election campaigning on social media: Politicians, audiences, and the mediation of political communication on Facebook and Twitter. Political Communication, 35, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syfers, L., Royer, Z., Anjierwerden, B., Rast, D. E., & Gaffney, A. M. (2024). Our group is worth the fight: Group cohesion is embedded in willingness to fight or die for relatively deprived political groups during national elections. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 10, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, D., Huang, Q., & Gabdulhakov, R. (2020). Mediated visibility as making vitriol meaningful. In S. Polak, & D. Trottier (Eds.), Violence and trolling on social media. History, affect, and effects of online vitriol (pp. 26–46). Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, J., Phua, J., Pan, S., & Yang, C. (2020). Intergroup contact, COVID-19 news consumption, and the moderating role of digital media trust on prejudice toward Asians in the United States: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22, e22767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2019). United Nations strategy and plan of action on hate speech. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/advising-and-mobilizing/Action_plan_on_hate_speech_EN.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- van Dijk, T. A. (2000). Ideology and discourse (2nd ed.). Pompeu Fabra University. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, T. A. (2009). Society and discourse: How social contexts influence text and talk. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, J. P., & Oliveira, L. (2024). Hate and perceived threats on the resettlement of Afghan refugees in Portugal. Societies, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., & Wei, L. (2020). Fear and hope, bitter and sweet: Emotion sharing of cancer community on twitter. Social Media + Society, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismueller, J., Harrigan, P., Coussement, K., & Tessitore, T. (2022). What makes people share political content on social media? The role of emotion, authority and ideology. Computers in Human Behavior, 129, 107150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K., Code, C., Dornan, C., Ahmad, N., Hébert, P., & Graham, I. (2004). The reporting of theoretical health risks by the media: Canadian newspaper reporting of potential blood transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. BMC Public Health, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S., Chen, Y., Vojta, S., & Chen, Y. (2022). More aggressive, more retweets? Exploring the effects of aggressive climate change messages on Twitter. New Media & Society, 26, 4409–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappettini, F., Ponton, D. M., & Larina, T. V. (2021). Emotionalisation of contemporary media discourse: A research agenda. Russian Journal of Linguistics, 25, 586–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., & Caverlee, J. (2018). Vitriol on social media: Curation and investigation. In S. Staab, O. Koltsova, & D. Ignatov (Eds.), Social informatics. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Żakowska, M., & Domalewska, D. (2019). Factors determining polish parliamentarians’ tweets on migration: A case study of Poland. Czech Journal of Political Science, XXVI(3), 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuk, P., & Żuk, P. (2020). ‘Euro-Gomorrah and Homopropaganda’: The culture of fear and ‘rainbow scare’ in the narrative of right-wing populists media in Poland as part of the election campaign to the European Parliament in 2019. Discourse, Context & Media, 33, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date of Publication | Content of the Tweet |

|---|---|

| 28 November 2020 07:43:59 | I got you, moots |

| 28 November 2020 08:56:52 | I’m jealous again:)) |

| 28 November 2020 08:57:11 | why won’t he ever talk to me on the phone |

| 28 November 2020 09:14:42 | I had a bad dream again |

| 28 November 2020 09:14:51 | third day in a row |

| 28 November 2020 10:01:10 | Dominic is coming soon, and I’m still sad |

| 28 November 2020 10:07:56 | @Anonymous-User Me too, but I remember only one :( |

| 28 November 2020 16:00:59 | I’m sad because Dominic has already left |

| 28 November 2020 16:35:46 | I just want to stop worrying about everything and just be happy |

| 28 November 2020 16:47:19 | he’s ignoring my tweets again, I’m feeling terrible |

| 28 November 2020 16:51:06 | my friend hasn’t written back to me for a few days and she reads so hah;) I will do the same |

| 28 November 2020 16:51:59 | exactly https://twitter.com/Link anonymised |

| 28 November 2020 16:52:55 | cute https://twitter.com/Link anonymised |

| 28 November 2020 17:06:11 | me too ;(https://twitter.com/Link anonymised |

| 28 November 2020 17:43:18 | I feel better after the walk |

| 28 November 2020 17:47:37 | and yet walking helps |

| 28 November 2020 18:23:55 | hot https://twitter.com/Link anonymised |

| 28 November 2020 18:37:59 | my head…. is bursting |

| 28 November 2020 20:18:51 | look what I got, I baked vege gingerbread https://Link anonymised |

| 28 November 2020 20:50:38 | good night https://Link anonymised |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Domalewska, D. Online Verbal Aggression on Social Media During Times of Political Turmoil: Discursive Patterns from Poland’s 2020 Protests and Election. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030146

Domalewska D. Online Verbal Aggression on Social Media During Times of Political Turmoil: Discursive Patterns from Poland’s 2020 Protests and Election. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030146

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomalewska, Dorota. 2025. "Online Verbal Aggression on Social Media During Times of Political Turmoil: Discursive Patterns from Poland’s 2020 Protests and Election" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030146

APA StyleDomalewska, D. (2025). Online Verbal Aggression on Social Media During Times of Political Turmoil: Discursive Patterns from Poland’s 2020 Protests and Election. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030146