Challenges for NGO Communication Practitioners in the Disinformation Era: A Qualitative Study Exploring Generation Z’s Perception of Civic Engagement and Their Vulnerability to Online Fake News

Abstract

1. Introduction

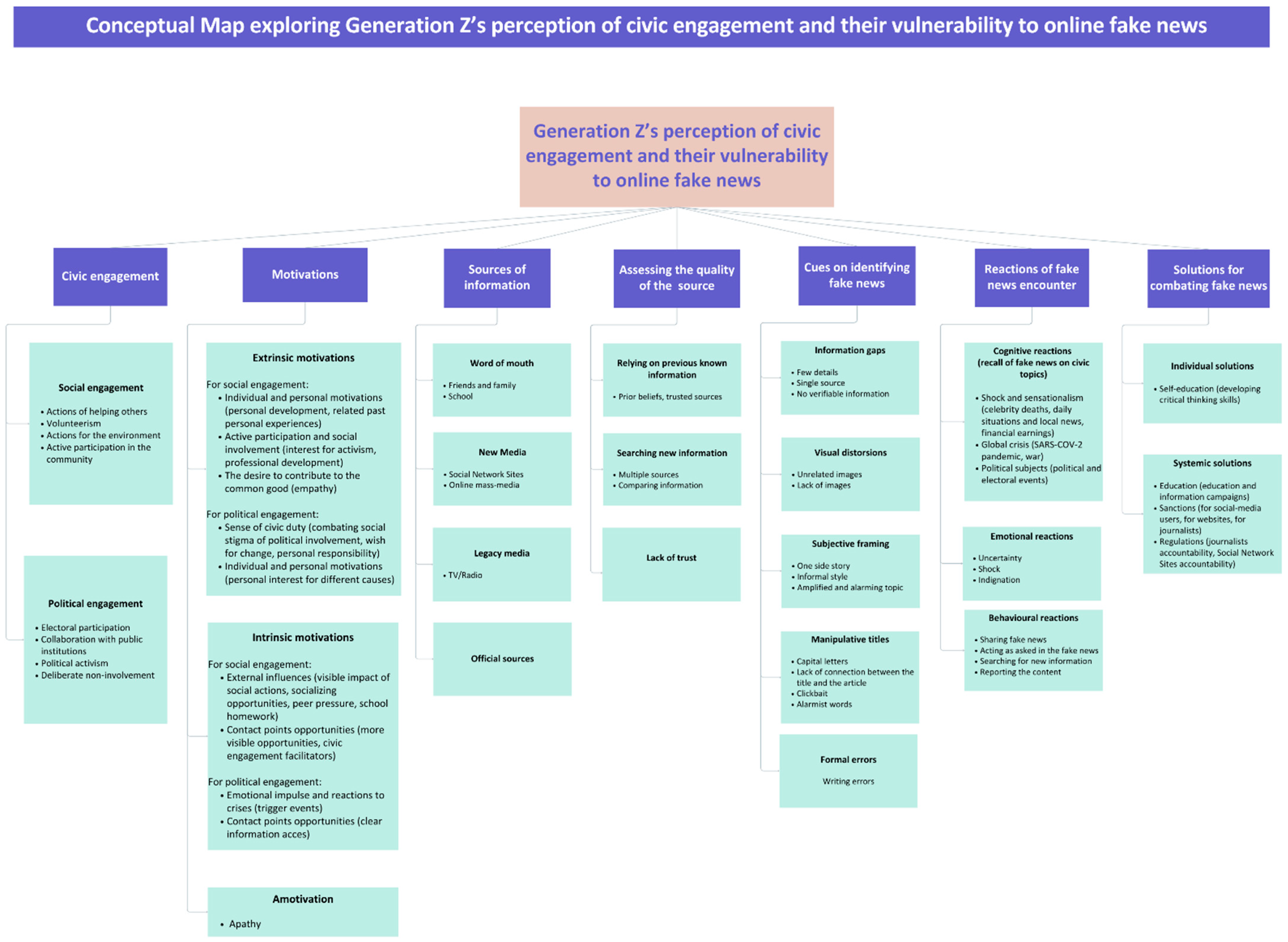

- O1:

- To explore the perceptions of Gen Z regarding civic engagement.

- O2:

- To identify the motivations behind Gen Z’s civic engagement.

- O3:

- To explore the media and information sources Gen Z uses concerning civic engagement.

- O4:

- To assess Gen Z’s exposure to fake news related to civic topics.

- O5:

- To examine the cues Gen Z considers when identifying fake news.

- O6:

- To examine the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural responses of Gen Z to fake news.

- O7:

- To explore Gen Z’s perceptions of solutions for combating fake news.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gen Z’s Vulnerability to Fake News

2.2. Civic NGOs and Their Role in Combating Fake News

2.3. Youth’s Perception of Civic Engagement

2.4. Youth’s Motivation for Civic Engagement

2.5. Youth Sources of Information Concerning Civic Engagement

2.6. Youth and Fake News Exposure

2.7. Cues to Identify Fake News

2.8. Reactions After Fake News Encounters in Civic Context

2.9. Solutions for Combating Fake News

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Understanding Civic Engagement

4.2. Motivation for Civic Engagement

4.3. Sources of Information on Civic Topics

4.4. Fake News Exposure

4.5. Reactions After Fake News Encounters

4.6. Cues on Fake News Identification

4.7. Solutions for Combating Fake News

5. Discussion

6. Managerial Implications

7. Theoretical Implications and Future Studies

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adler, R. P., & Goggin, J. (2005). What do we mean by “civic engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3(3), 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïmeur, E., Amri, S., & Brassard, G. (2023). Fake news, disinformation and misinformation in social media: A review. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C., Macedo-Rouet, M., de Carvalho, V. B., Castilhos, W., Ramalho, M., Amorim, L., & Massarani, L. (2023). When does credibility matter? The assessment of information sources in teenagers’ navigation regimes. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 55(1), 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rawi, A., O’Keefe, D., Kane, O., & Bizimana, A. J. (2021). Twitter’s fake news discourses around climate change and global warming. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 729818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikewuyo, A. O. (2025). Is AI stirring innovation or chaos? Psychological determinants of AI Fake News Exposure (AI-FNE) and its effects on young adults. Journalism and Media, 6(2), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V., Ng, W. Z., Soo, M. C., Han, G. J., & Lee, C. J. (2022). Infodemic and fake news—A comprehensive overview of its global magnitude during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021: A scoping review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 78, 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S., & Kim, D. J. (2023). Examining users’ news sharing behaviour on social media: Role of perception of online civic engagement and dual social influences. Behaviour & Information Technology, 42(8), 1194–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B., Chaskin, R. J., & McGregor, C. (2020). Promoting civic and political engagement among marginalized urban youth in three cities: Strategies and challenges. Children and Youth Services Review, 116, 105184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, J. N. (2022). Do service provision NGOs perform civil society functions? Evidence of NGOs’ relationship with democratic participation. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 51(1), 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruinenberg, H., Sprenger, S., Omerović, E., & Leurs, K. (2021). Practicing critical media literacy education with/for young migrants: Lessons learned from a participatory action research project. International Communication Gazette, 83(1), 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busetto, L., Wick, W., & Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurological Research and Practice, 2(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, P. R., Cuervo Sanchez, S. L., & Daros, M. A. (2020). Citizen engagement in the contemporary era of fake news: Hegemonic distraction or control of the social media context? Postdigital Science and Education, 2(1), 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R. F., & Hawkins, J. D. (1996). The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In J. D. Hawkins (Ed.), Delinquency and crime: Current theories (pp. 149–197). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Independent Journalism. (2024). Digital literacy transformation for Romanian youth. CJI Reports. Available online: https://cji.ro/en/digital-literacy-transformation-for-romanian-youth/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Center for Independent Journalism. (2025). Media literacy. Available online: https://cji.ro/en/subject/media-literacy/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Chittum, J. R., Enke, K. A. E., & Finley, A. P. (2022). The effects of community-based and civic engagement in higher education (pp. 1–30). American Association of Colleges and Universities. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED625877.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Chryssanthopoulou, K. (2023). Fake news deconstructed teens and civic engagement: Can tomorrow’s voters spontaneously become news literate? In K. Fowler-Watt, & J. McDougall (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of media misinformation. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, C., Rivas, J., Franco, R., Gómez-Plata, M., & Kanacri, B. (2023). Digital media use on school civic engagement: A parallel mediation model. Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal, 31(75), 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Corney, T., Williamson, H., Holdsworth, R., & Shier, H. (2020). Approaches to youth participation in youth and community work practice: A critical dialogue. Youth Workers’ Association. Available online: https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/server/api/core/bitstreams/7b468dc4-2b67-4a13-918f-bacc16c93ff5/content (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Corporate Europe Observatory. (2025). False alarm: Fake news and the right fuel attack on NGOs. Available online: https://corporateeurope.org/en/2025/03/false-alarm-fake-news-and-right-fuel-attack-ngos (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Damstra, A., Boomgaarden, H. G., Broda, E., Lindgren, E., Strömbäck, J., Tsfati, Y., & Vliegenthart, R. (2021). What does fake look like? A review of the literature on intentional deception in the news and on social media. Journalism Studies, 22(14), 1947–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvekot, S., Valgas, C. M., de Haan, Y., & de Jong, W. (2024). How youth define, consume, and evaluate news: Reviewing two decades of research. New Media & Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, J., & Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22(3), 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. (2022). Guidelines for teachers and educators on tackling disinformation and promoting digital literacy through education and training. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/28248 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- European Commission: High Level Group of Fake News and Online Disinformation. (2018). A multidimensional approach to disinformation. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/final-report-high-level-expert-group-fake-news-and-online-disinformation (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Fârte, G.-I., Obadă, D.-R., Gherguț-Babii, A.-N., & Dabija, D. C. (2025). Building corporate immunity: How do companies increase their resilience to negative information in the environment of fake news? Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, K., Robichau, R. W., Alexander, J. K., Mackenzie, W. I., & Scherer, R. F. (2022). How a nonprofitness orientation influences collective civic action: The effects of civic engagement and political participation. Voluntas, 33, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, A., & Oliveira, L. (2017). The current state of fake news: Challenges and opportunities. Procedia Computer Science, 121, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiling, I. (2019). Detecting misinformation in online social networks: A think-aloud study on user strategies. Studies in Communication and Media, 4, 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerston, L. N. (2021). Public policymaking in a democratic society: A guide to civic engagement. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Guess, A., Nagler, J., & Tucker, J. (2019). Less than you think: Prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science Advances, 5(1), eaau4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, A. M., Lerner, M., Lyons, B., Montgomery, J. M., Nyhan, B., Reifler, J., & Sircar, N. (2020). A digital media literacy intervention increases discernment between mainstream and false news in the United States and India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(27), 15536–15545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero-Diz, P., Conde-Jiménez, J., & Reyes de Cózar, S. (2020). Teens’ motivations to spread fake news on WhatsApp. Social Media + Society, 6(3), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, C. G., Galletta, D., Crawford, J., & Shirsat, A. (2021). Emotions: The unexplored fuel of fake news on social media. Journal of Management Information Systems, 38(4), 1039–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, P. N., Neudert, L. M., Prakash, N., & Vosloo, S. (2021). Digital misinformation/disinformation and children. UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/innocenti/media/856/file/UNICEF-Global-Insight-Digital-Mis-Disinformation-and-Children-2021.pdf (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Huang, G., Jia, W., & Yu, W. (2024). Media literacy interventions improve resilience to misinformation: A meta-analytic investigation of overall effect and moderating factors. Communication Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSCOP Research. (2021). Public mistrust: West vs. East—The rise of nationalist trend in era of disinformation and fake news [Survey Report]. Available online: https://www.inscop.ro/en/october-2021-public-distrust-west-vs-east-the-rise-of-nationalism-in-the-disinformation-era-and-the-fake-news-phenomenon-3rd-edition/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Jain, L., Velez, L., Karlapati, S., Forand, M., Kannali, R., Yousaf, R. A., Ahmed, R., Sarfraz, Z., Sutter, P. A., Tallo, C. A., & Ahmed, S. (2025). Exploring problematic TikTok use and mental health issues: A systematic review of empirical studies. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahne, J., Lee, N. J., & Feezell, J. T. (2012). Digital media literacy education and online civic and political participation. International Journal of Communication, 6, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M. L., & Idris, I. K. (2019). Recognise misinformation and verify before sharing: A reasoned action and information literacy perspective. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(12), 1194–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, B., & Rosenstiel, T. (2007). The elements of journalism: What newspeople should know and the public should expect (1st ed.). Three Rivers Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kreft, J., Boguszewicz-Kreft, M., & Hliebova, D. (2024). Under the fire of disinformation. Attitudes towards fake news in the Ukrainian frozen war. Journalism Practice, 18(10), 2667–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K. K., & Geethakumari, G. (2014). Detecting misinformation in online social networks using cognitive psychology. Human-Centric Computing and Information Sciences, 4(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55(1), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N. J., Shah, D. V., & McLeod, J. M. (2013). Processes of political socialization: A communication mediation approach to youth civic engagement. Communication Research, 40(5), 669–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilja, J., Eklund, N., & Tottie, E. (2024). Civic literacy and disinformation in democracies. Social Sciences, 13(8), 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S., Mascheroni, G., & Stoilova, M. (2023). The outcomes of gaining digital skills for young people’s lives and wellbeing: A systematic evidence review. New Media & Society, 25(5), 1176–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdin, R. (2022). How much the war in Ukraine affects Romanians and how much of it is fake news: The panic over product prices. Polis. Journal of Political Science, 10(2 (36)), 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, V. I., & Castaneda, L. (2022). Developing digital literacy for teaching and learning. In Handbook of open, distance and digital education (pp. 1–20). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, J., & Rega, I. (2022). Beyond solutionism: Differently motivating media literacy. Media and Communication, 10(4), 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrew, S., & Byrne, V. L. (2022). Conversations after lateral reading: Supporting teachers to focus on process, not content. Computers & Education, 185, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Media Literacy Now. (2025). What is media literacy? Available online: https://medialiteracynow.org/challenge/what-is-media-literacy/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Mediawise. (2018). Propaganda lab. Available online: https://mediawise.ro/atelier-nou-laborator-de-propaganda-stii-sa-recunosti-propaganda/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Meel, P., & Vishwakarma, D. K. (2020). Fake news, rumor, information pollution in social media and web: A contemporary survey of state-of-the-arts, challenges and opportunities. Expert Systems with Applications, 153, 112986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchior, C., & Oliveira, M. (2024). A systematic literature review of the motivations to share fake news on social media platforms and how to fight them. New Media & Society, 26(2), 1127–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercenier, H., Wiard, V., & Dufrasne, M. (2021). Teens, social media, and fake news: A user’s perspective. In G. Lopez-Garcia, D. Palau-Sampio, B. Palomo, E. C. Domínguez, & P. Masip (Eds.), Politics of disinformation: The influence of fake news on the public sphere (pp. 159–172). Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailidis, P., & Thevenin, B. (2013). Media literacy as a core competency for engaged citizenship in participatory democracy. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(11), 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailidis, P., & Viotty, S. (2017). Spreadable spectacle in digital culture: Civic expression, fake news, and the role of media literacies in “Post-Fact” society. American Behavioral Scientist, 61(4), 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, I., Dezso, N., Ceană, D. E., & Voidăzan, T. S. (2025). Fake news: Offensive or defensive weapon in information warfare. Social Sciences, 14(8), 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmuration. (2024). Understanding gen Z: Barriers to civic engagement. Available online: https://cdn.sanity.io/files/04war3gn/production/b86f6dcbf2dd859a0d3c25742a33194ec763701a.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Obadă, D.-R. (2019). Sharing fake news about brands on social media: A new conceptual model based on flow theory. Argumentum. Journal of the Seminar of Discursive Logic, Argumentation Theory and Rhetoric, 17(2), 144–166. [Google Scholar]

- Obadă, D.-R., & Dabija, D.-C. (2022). “In Flow”! Why do users share fake news about environmentally friendly brands on social media? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(8), 4861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oden, A., & Porter, L. (2023). The kids are online: Teen social media use, civic engagement, and affective polarization. Social Media + Society, 9(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H., Qin, K., & Ji, M. (2022). Can social network sites facilitate civic engagement? Assessing dynamic relationships between social media and civic activities among young people. Online Information Review, 46(1), 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangrazio, L., & Sefton-Green, J. (2021). Digital rights, digital citizenship and digital literacy: What’s the difference? Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 10(1), 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G., Bear, A., Collins, E. T., & Rand, D. G. (2020). The implied truth effect: Attaching warnings to a subset of fake news headlines increases perceived accuracy of headlines without warnings. Management Science, 66(11), 4944–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2021). The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(5), 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Curiel, C., Rúas-Araújo, X., & Barrientos-Báez, A. (2022). Misinformation and factchecking on the disturbances of the Procés of Catalonia. Digital impact on public and media. KOME, An International Journal of Pure Communication Inquiry, 10(2), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatak, J., & Mikkelsen, I. (2021). Does social media engagement translate to civic engagement offline? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(5), 1079–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, G. (2023). Internet users’ utopian/dystopian imaginaries of society in the digital age: Theorizing critical digital literacy and civic engagement. New Media & Society, 25(5), 1265–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszna, P., & Galus, A. (2020). Promoting active youth: Evidence from Polish NGO’s civic education programme in Eastern Europe. Journal of International Relations and Development, 23(1), 210–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S., & Bansal, D. (2023). A review on fake news detection 3T’s: Typology, time of detection, taxonomies. International Journal of Information Security, 22, 177–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P. K., & Chahar, S. (2021). Fake profile detection on social networking websites: A comprehensive review. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, 1(3), 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, D. M., & Black, J. (2024). Who gets caught in the web of lies?: Understanding susceptibility to phishing emails, fake news headlines, and scam text messages. Human Factors, 66(6), 1742–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selnes, F. N. (2024). Adolescents’ experiences and (re)action towards fake news on social media: Perspectives from Norway. Humanities Social Sciences Communications, 11, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shephard, M. P., Robertson, D. J., Huhe, N., & Anderson, A. (2023). Everyday non-partisan fake news: Sharing behavior, platform specificity, and detection. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1118407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skurka, C., Liao, M., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2023). Tuning out (political and science) news? A selective exposure study of the news finds me perception. Communication Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. (2022). Set charge about change: The effects of a long-term youth civic engagement program. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 5(2), 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sormanen, N., Rantala, E., Lonkila, M., & Wilska, T. A. (2022). News consumption repertoires among Finnish adolescents: Moderate digital traditionalists, minimalist social media stumblers, and frequent omnivores. Nordicom Review, 43(2), 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2023). Number of Instagram users in Romania. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1017987/instagram-users-romania/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Statista. (2024). False news worldwide—Statistics & facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/6341/fake-news-worldwide/#topicOverview (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Swart, J. (2021). Experiencing algorithms: How young people understand, feel about, and engage with algorithmic news selection on social media. Social Media + Society, 7(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, J. (2023). Tactics of news literacy: How young people access, evaluate, and engage with news on social media. New Media & Society, 25(3), 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, J., & Broersma, M. (2022). The trust gap: Young people’s tactics for assessing the reliability of political news. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 27(2), 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddicken, M., & Wolff, L. (2020). ‘Fake News’ in science communication: Emotions and strategies of coping with dissonance online. Media and Communication, 8(1), 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarozzi, M. (2020). Role of NGOs in global citizenship education. In The Bloomsbury handbook of global education and learning (pp. 133–148). Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaliki, L. (2022). Constructing young selves in a digital media ecology: Youth cultures, practices and identity. Information, Communication & Society, 25(4), 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungur-Brehoi, C. (2022). Information safety: Top five fake news in the Romanian media (2022). International Journal of Legal and Social Order, 1(1), 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Arias, A., Arango-Botero, D. M., Cardona-Acevedo, S., Paredes Delgado, S. S., & Gallegos, A. (2023). Understanding the spread of fake news: An approach from the perspective of young people. Informatics, 10(2), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissenberg, J., De Coninck, D., Mascheroni, G., Joris, W., & d’Haenens, L. (2023). Digital skills and digital knowledge as buffers against online mis/disinformation? Findings from a survey study among young people in Europe. Social Media + Society, 9(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, C., & Derakhshan, H. (2017). Information disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policymaking [Council of Europe Report]. DGI. Available online: https://edoc.coe.int/en/module/ec_addformat/download?cle=5905aa3361a00b7d9356fa6cf222396d&k=d53583a5338dd57b4b6889c531b81b39 (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Focus Group No. | Female Participants | Male Participants | Total Participants per Focus Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| 3 | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| 4 | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| 5 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| 6 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| 7 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| 8 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Research Question | Research Objective | Operationalised Concept | Focus Group Questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| RQ1: What are Gen Z’s perceptions of civic engagement? | To explore the perceptions of Gen Z regarding civic engagement. | Civic engagement | What understanding do you have of “civic engagement”? Describe a situation you were civically engaged in. |

| RQ2: What are Gen Z’s motivations for civic engagement? | To identify the motivations behind Gen Z’s civic engagement. | Types of motivation (for civic engagement) | What motivated you to get involved in civic actions? If not, what would motivate you to become involved in civic actions? |

| RQ3: What sources of information/media sources concerning civic engagement does Gen Z use? | To explore the media and information sources Gen Z use concerning civic engagement. | Sources of information | What sources do you use to inform yourself on civic (social and political) subjects? |

| RQ4: Are Gen Z people exposed to fake news concerning social and political topics? | To assess Gen Z’s exposure to fake news related to social and political topics. | Fake news exposure | Describe the situation when you have encountered fake news on social/political topics. |

| RQ5: What are the cues Gen Z people take into consideration to identify fake news? | To examine the cues Gen Z considers when identifying fake news. | Cues on fake news identification | What are the characteristics by which you identify fake news? |

| RQ6: What cognitive, emotional, and behavioural responses are triggered by fake news in Gen Z individuals? | To examine the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural responses of Gen Z to fake news. | Recall of fake news topics | Describe the situation when you have encountered fake news on social/political topics. |

| Triggered emotions | What emotions did you experience when you encountered the fake news? | ||

| Triggered actions | What actions did you take when you encountered the fake news? | ||

| RQ7: What are Gen Z’s perceptions of the solutions for combating fake news? | To explore Gen Z’s perceptions of solutions for combating fake news. | Solutions for combating fake news | How do you think the phenomenon of fake news could be limited? Which entities do you think would be responsible for fake news? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gherguț-Babii, A.-N.; Poleac, G.; Obadă, D.-R. Challenges for NGO Communication Practitioners in the Disinformation Era: A Qualitative Study Exploring Generation Z’s Perception of Civic Engagement and Their Vulnerability to Online Fake News. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030136

Gherguț-Babii A-N, Poleac G, Obadă D-R. Challenges for NGO Communication Practitioners in the Disinformation Era: A Qualitative Study Exploring Generation Z’s Perception of Civic Engagement and Their Vulnerability to Online Fake News. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030136

Chicago/Turabian StyleGherguț-Babii, Alexandra-Niculina, Gabriela Poleac, and Daniel-Rareș Obadă. 2025. "Challenges for NGO Communication Practitioners in the Disinformation Era: A Qualitative Study Exploring Generation Z’s Perception of Civic Engagement and Their Vulnerability to Online Fake News" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030136

APA StyleGherguț-Babii, A.-N., Poleac, G., & Obadă, D.-R. (2025). Challenges for NGO Communication Practitioners in the Disinformation Era: A Qualitative Study Exploring Generation Z’s Perception of Civic Engagement and Their Vulnerability to Online Fake News. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030136