The Role of Public Relations in the Employability and Entrepreneurship Services of Andalusian Public Universities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How do the public relations strategies implemented by the employability and entrepreneurship services of Andalusian public universities have an impact on the labor market insertion of students?

- What are the public relations strategies most used by university services to connect students with the labor market and encourage entrepreneurship?

- How does the management of social networks and digital presence influence the visibility of employment and entrepreneurship opportunities for students?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Public Relations in Andalusian Public Universities

2.2. Strategies Employed in Andalusian University Services for Employability and Entrepreneurship

2.3. Digital Strategies and Social Networks

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Outcome of Social Media Strategies from Non-Participant Observation of Websites

- -

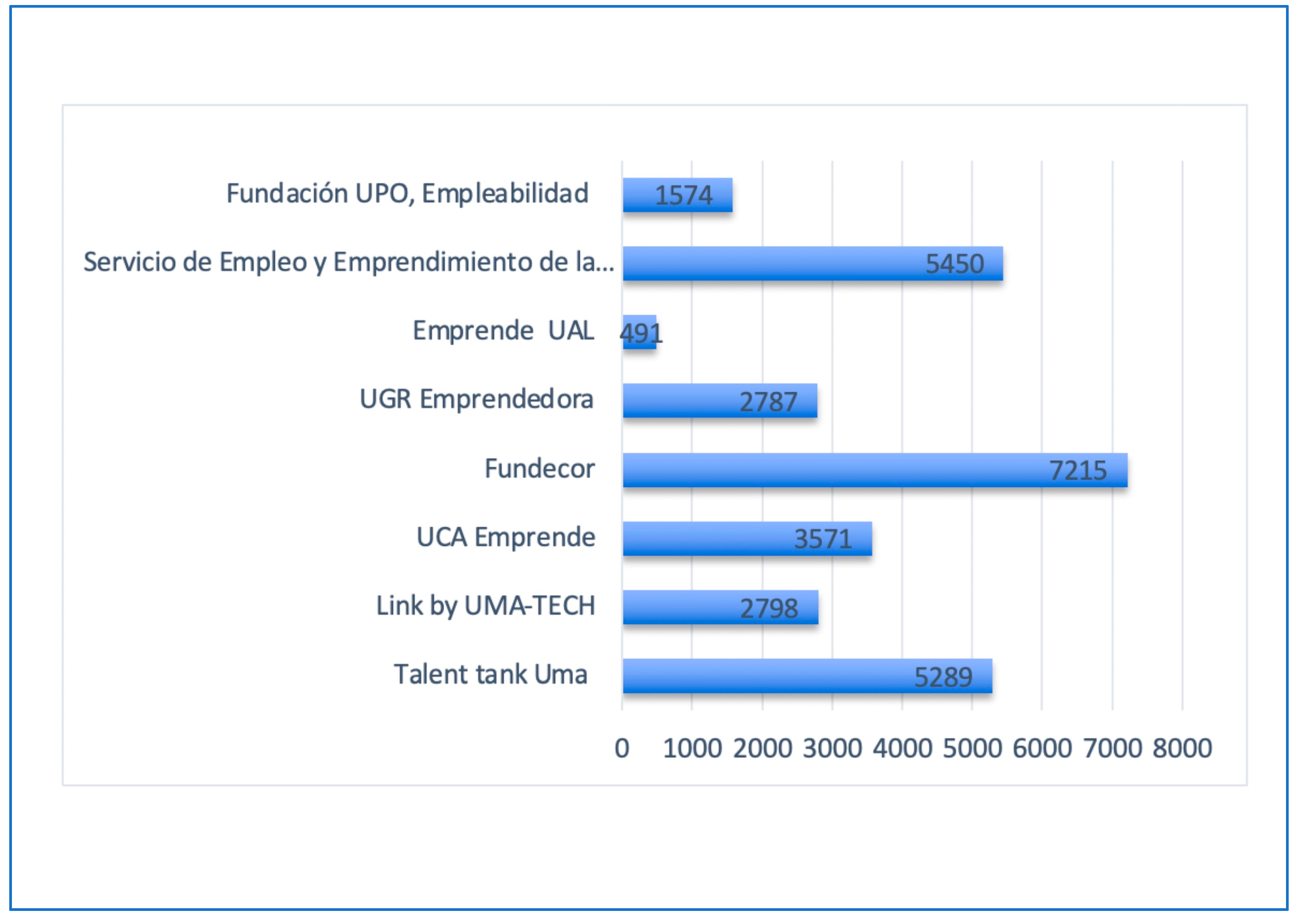

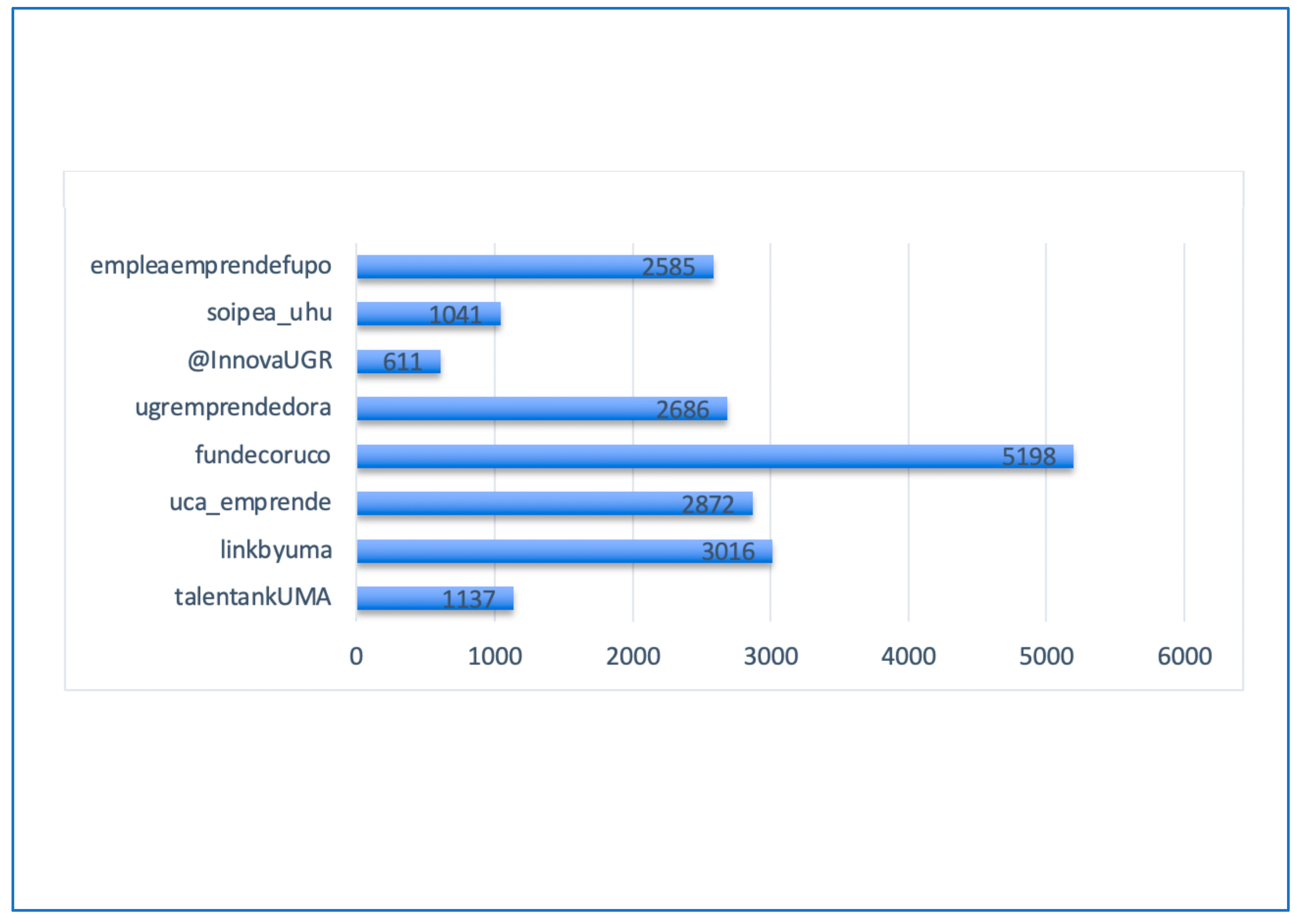

- University of Malaga (UMA): Offers a comprehensive strategy in employability, entrepreneurship, and innovation through Talent Tank and Link by UMA-Atech. Programs such as Talent and Job Hackathon and Talent and Job Softskills, focused on practical skills; Univergem, which promotes employability and equal opportunities for women; Factor-E, which provides feedback from the labor market; and Spin-Off, Polaris, and Key Program (specific programs of Link by UMA-Atech), which promote knowledge transfer, innovation, and project-based learning.

- -

- University of Cadiz: UCAEmprende promotes an entrepreneurial ecosystem with infrastructures such as El Olivillo, which offers coworking spaces and incubation offices. Also noteworthy is the course “Desafío Emprendedor Innovador”, an intensive 40 h training course focused on business innovation, and the UCAEmprende Juernes workshops, focused on key competencies. All with an applied approach and support for entrepreneurial students.

- -

- University of Cordoba (UCO): through Fundecor, connects university and business with paid internships, entrepreneurship counselling, and personalized guidance to professionalize ideas and projects.

- -

- University of Granada (UGR): through Viceinnova, promotes Living Labs, open innovation, and internships in social entities, promoting employability and community engagement.

- -

- University of Seville (US): through Alumni US, supports graduates with the Entrepreneurs Network: contests, pre-incubation, and coworking, and Professional Network: guidance, mentoring, and job offers.

- -

- University of Almeria (UAL): with EmprendeUAL, promotes creative collaboration, programs such as Retos Emprendedores and Jump, which integrate theory with practice, and mentoring services. Matilda Emprende supports women entrepreneurs, while the Ideas Fair connects students with investors.

- -

- University of Jaen (UJA): offers internships, incentives to companies, business incubators with advice and resources such as the Employment Portal and MOOC workshops for guidance and continuing education.

- -

- University of Huelva (UHU): the Employment and Entrepreneurship Service (SOIPEA) offers programs such as Un Paso Adelante that provide training in transversal and digital skills; the University Employment Forum allows direct contact with companies; UNIVERGEM promotes job placement for university women; and JOBVEN facilitates corporate presentations of companies to students.

- -

- Pablo de Olavide University (UPO): the UPO Foundation leads programs such as UPO-Emprende and SVQ Emprende, which offer advice, training, and mentoring for the development and consolidation of sustainable entrepreneurial projects.

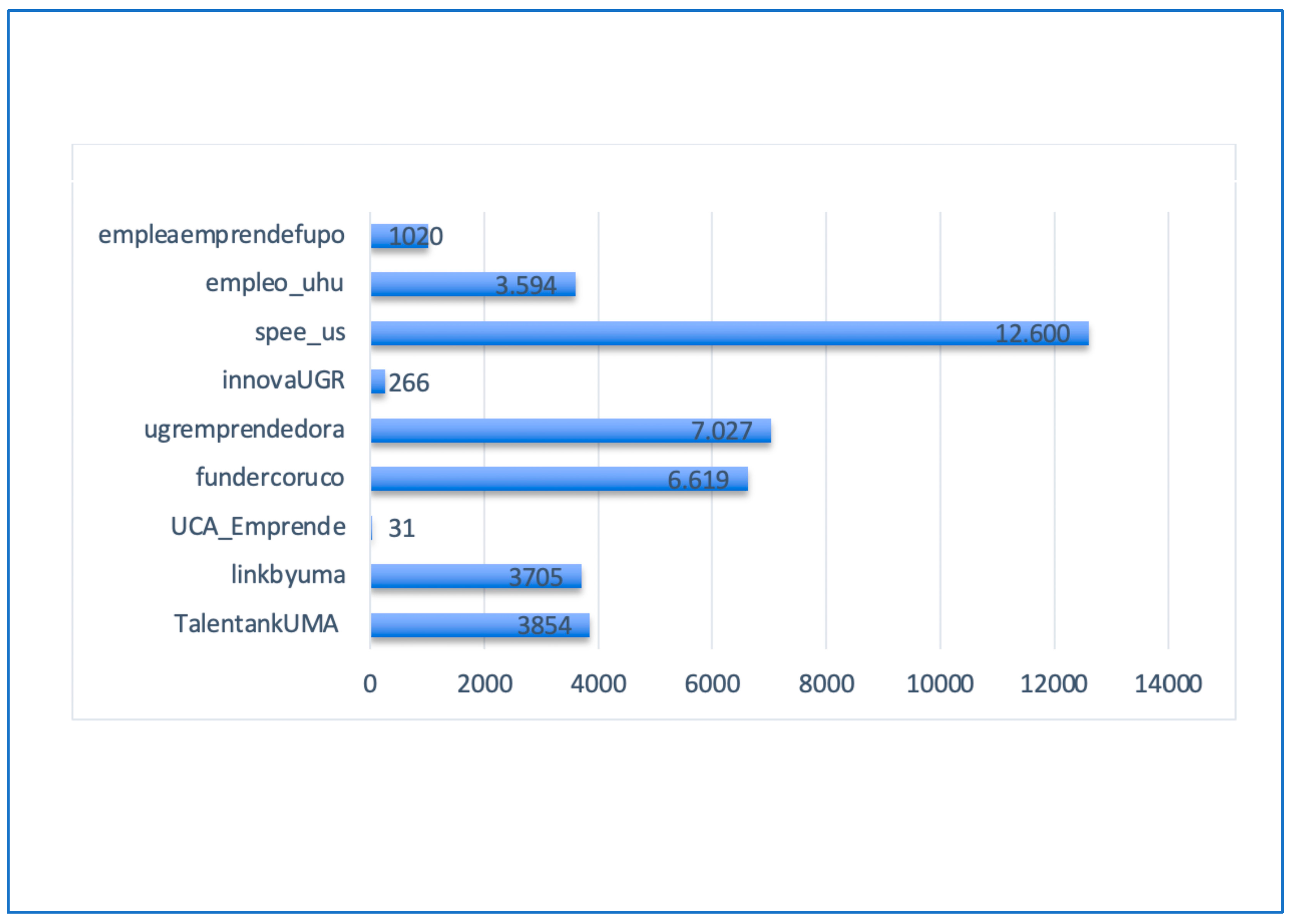

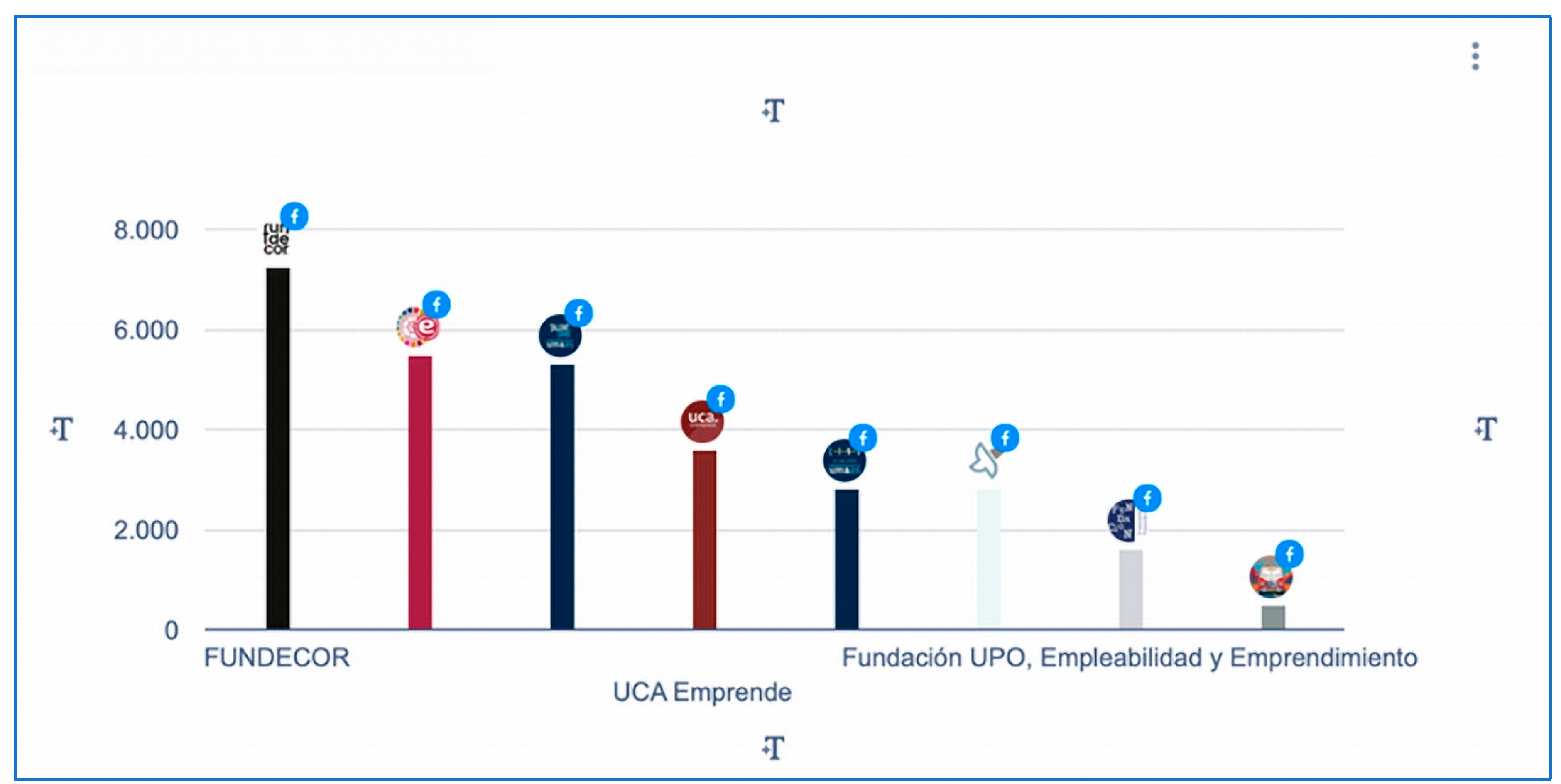

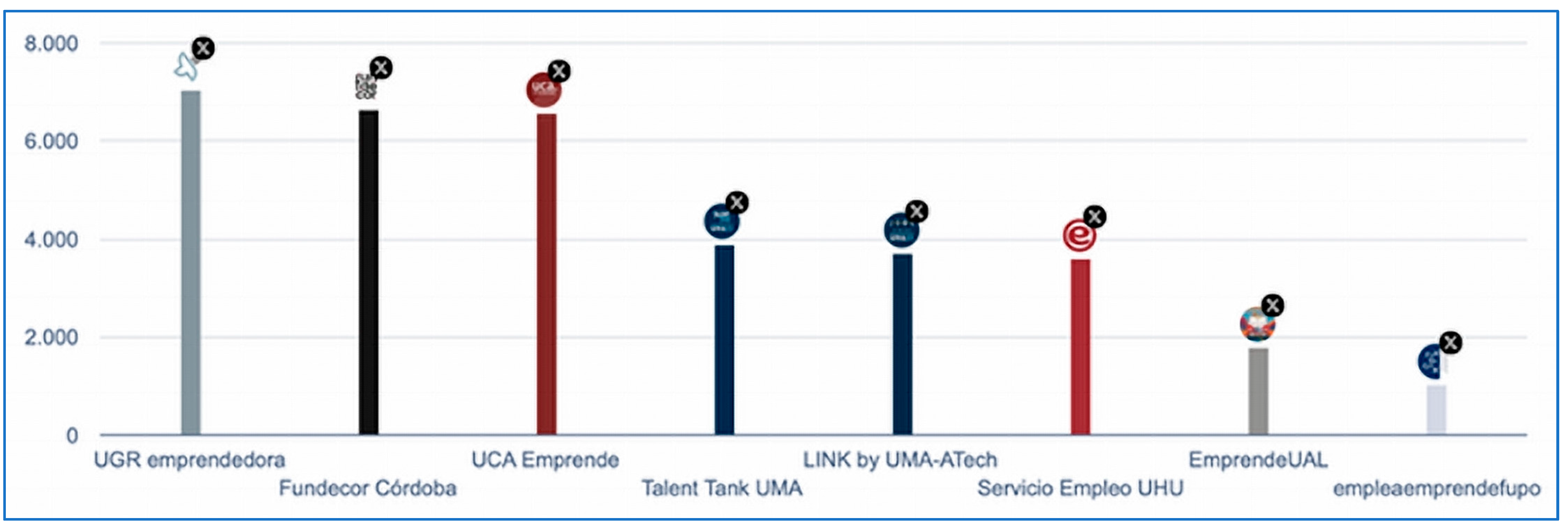

4.2. Analysis of Social Networks

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrantes, P., Silva, A. P., Backstrom, B., Neves, C., Falé, I., Jacquinet, M., Ramos, M. D. R., Magano, O., & Henriques, S. (2022). Transversal competences and employability: The impacts of distance learning university according to graduates’ follow-up. Education Sciences, 12(2), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIReF. (2020). Sistema Universitario Público Andaluz. Available online: https://www.airef.es/es/ (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Almansa-Martinez, A., & Ruiz-Mora, I. (Eds.). (2020). Presentación: Las Relaciones Públicas en el nuevo milenio: Retos y oportunidades. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 10(20), 01–04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso García, S., & Alonso García, M. D. M. (2014). Las redes sociales en las universidades españolas. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 33, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M. G., & Tomlinson, M. (2021). The changing value of higher education in England and Portugal: Massification, marketization and public good. European Educational Research Journal, 20(2), 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Forero, G. (2013). Digital communication: A proposal for analysis based on complex thought. Palabra Clave—Revista de Comunicación, 16(3), 673–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arboledas-Lérida, L., & Vázquez-Liñán, M. (2024). The commodification of academic research and its social legitimation: When the public communication of science becomes propaganda. Communication & Society, 37(3), 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askehave, I. (2007). The impact of marketization on higher education genres—The international student prospectus as a case in point. Discourse Studies, 9(6), 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausón, A. R. L.-L., & Carvajal, C. A. C. (2018). Implementación de una estrategia de marketing para la marca de agua embotellada manantial en Guayaquil. Espol. [Google Scholar]

- Bisani, S., & Jagannathan, A. (2022). Effectiveness of Moral Development Program for High School Adolescents in South India: A Matched Controlled Design. Journal of Applied Consciousness Studies, 10(2), 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, R., & Neveda, M. (2010). Employing discourse: Universities and graduate ‘employability’. Journal of Education Policy, 25(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos Salinas, L. (2013). Nuevas tecnologías en los gabinetes de comunicación de las universidades españolas/New communication technologies in Spanish university communication departments. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 3(6), 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo Durán, M. V., & Castillo Díaz, A. (2014). La transmisión de marca de las universidades españolas en sus portales webs. Historia y Comunicación Social, 18(0), 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado Molina, A. M., & Cuadrado Méndez, F. J. (2014). La reputación corporativa: Un nuevo enfoque de las competencias transversales en el EEES. REDU. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 12(1), 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A. (2010). Introducción a las relaciones públicas. Instituto de Investigación en Relaciones Públicas. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Esparcia, A., Castillero-Ostio, E., & Castillo-Díaz, A. (2020). The think tanks in Spain. Analysis of their digital communications strategies. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 77, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Esparcia, A., Guerra-Heredia, S., & Almansa-Martínez, A. (2017). Political communication and think tanks in Spain. Strategies with the media. El Profesional de la Información, 26(4), 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes Muñoz, M. A., Devece, C., & Peris Ortiz, M. (2024). University-level entrepreneurship education: A bibliometric review using tree of science. Multidisciplinary Journal for Education, Social and Technological Sciences, 11(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durango, A. (2014). Las redes sociales. IT Campus Academy. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Díaz, E., Jambrino-Maldonado, C., Iglesias-Sánchez, P. P., & de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. (2023). Web accessibility in Spanish city councils: A challenge for the democratic inclusion and well-being of citizens. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, C. (2022). An empirical study of alumni relations in technology enterprises [Doctoral dissertation, Fordham University]. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, S. P., Sousa, M. J., & Pereira, F. S. (2020). Distance learning perceptions from higher education students—The case of Portugal. Education Sciences, 10(12), 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Sánchez, T. F., & Rumbo Arcas, B. (2022). La estrategia discursiva sobre la empleabilidad en el Espacio Europeo de Educación Superior: Propósito y desafío en la configuración de los planes de estudio. Revista de Investigación en Educación, 20(2), 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzhausen, D. R. (2000). Postmodern values in public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 12(1), 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S., Tahat, K., El Gody, A., & Al Mansoori, A. (2025). Employing social media in building academic brands of the UAE’s universities: A comparative analysis. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies, 15(1), e202505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Andalucía. (2023). La universidad pública andaluza aporta al PIB regional un 3%, el mayor índice de toda España. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/presidencia/portavoz/educacion/183845/ConsejeriadeUniversidad/universidadpublica/PIB/ProductoInteriorBruto (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Ki, E.-J., Pasadeos, Y., & Ertem-Eray, T. (2019). Growth of public relations research networks: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Public Relations Research, 31(1–2), 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiołek, A., Karyy, O., & Halkiv, L. (2020). Comparative analysis of the practice of internet use in the marketing activities of higher education institutions in Poland and Ukraine. Comparative Economic Research. Central and Eastern Europe, 23(2), 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, E. (2019). Massification, marketisation and loss of differentiation in pre-entry marketing materials in UK higher education. Social Sciences, 8(11), 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macnamara, J. (2016). Organizational listening: The missing essential in public communication. Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado Castro, J., Gómez Pérez, R., Aguirre Valverde, D., & Andrade Arias, M. (2023). Relaciones públicas: El rol de la comunicación y su incidencia en la transformación digital: Public relations: The role of communication and its impact on digital transformation. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 4(1), 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresova, P., Hruska, J., & Kuca, K. (2020). Social media university branding. Education Sciences, 10(3), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Ruiz, A., Durán Mañes, A., & Fernández Beltrán, F. (2014). Relaciones públicas y comunicación para un entorno de crisis. El caso de las universidades andaluzas. Historia y Comunicación Social, 19, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogaji, E., & Yoon, H. (2019). Thematic analysis of marketing messages in UK universities’ prospectuses. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(7), 1561–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero Esteva, A., Castillo Díaz, A., & Rodríguez Rodríguez, A. M. (2021). Sedes webs de las universidades cubanas. Análisis de su presencialidad en internet. Vivat Academia, 154, 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, Á., Fuentes-Lara, C., Zurro-Antón, N., Tench, R., Zerfass, A., Vercic, D., & Verhoeven, P. (2023). Excelencia en comunicación: Cómo desarrollar, dirigir y liderar comunicaciones excepcionales (European communication monitor) (1st ed.). Fundació per a la Universitat Oberta de Catalunya. [Google Scholar]

- Narváez, J. Á. (2023). El rector defiende el papel de las universidades públicas como motor de crecimiento de Andalucía [Interview]. Available online: https://www.uma.es/sala-de-prensa/noticias/el-rector-defiende-el-papel-de-las-universidades-publicas-como-motor-de-crecimiento-de-andalucia/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Ndung’u, J., Vertinsky, I., & Onyango, J. (2023). The relationship between social media use, social media types, and job performance amongst faculty in Kenya private universities. Heliyon, 9(12), e22946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicer Jordá, M. T. (2024). El grado de publicidad y relaciones públicas en España. Revisión de planes docentes. Vivat Academia, 157, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D., Leitão, J., Oliveira, T., & Peirone, D. (2023). Proposing a holistic research framework for university strategic alliances in sustainable entrepreneurship. Heliyon, 9(5), e16087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

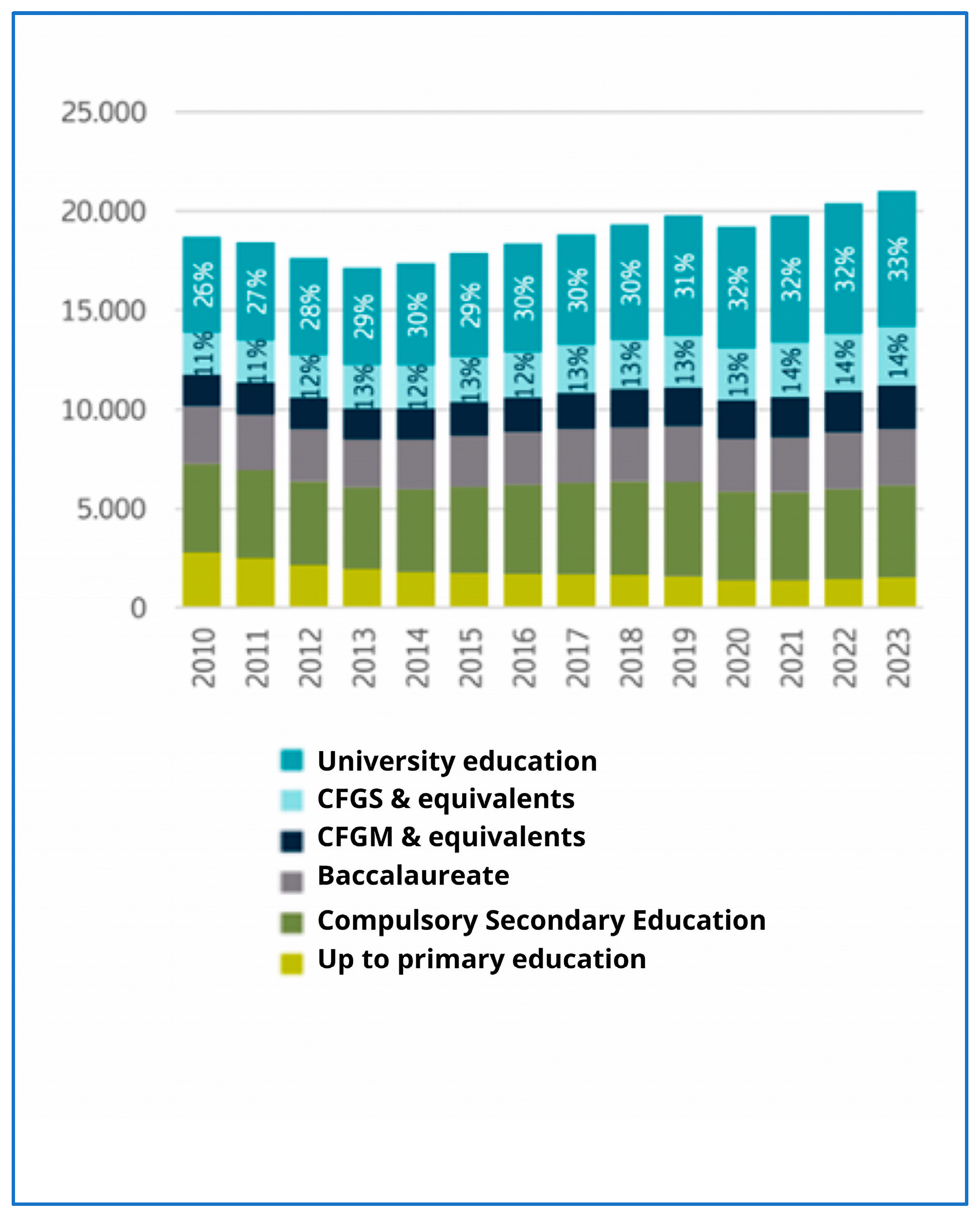

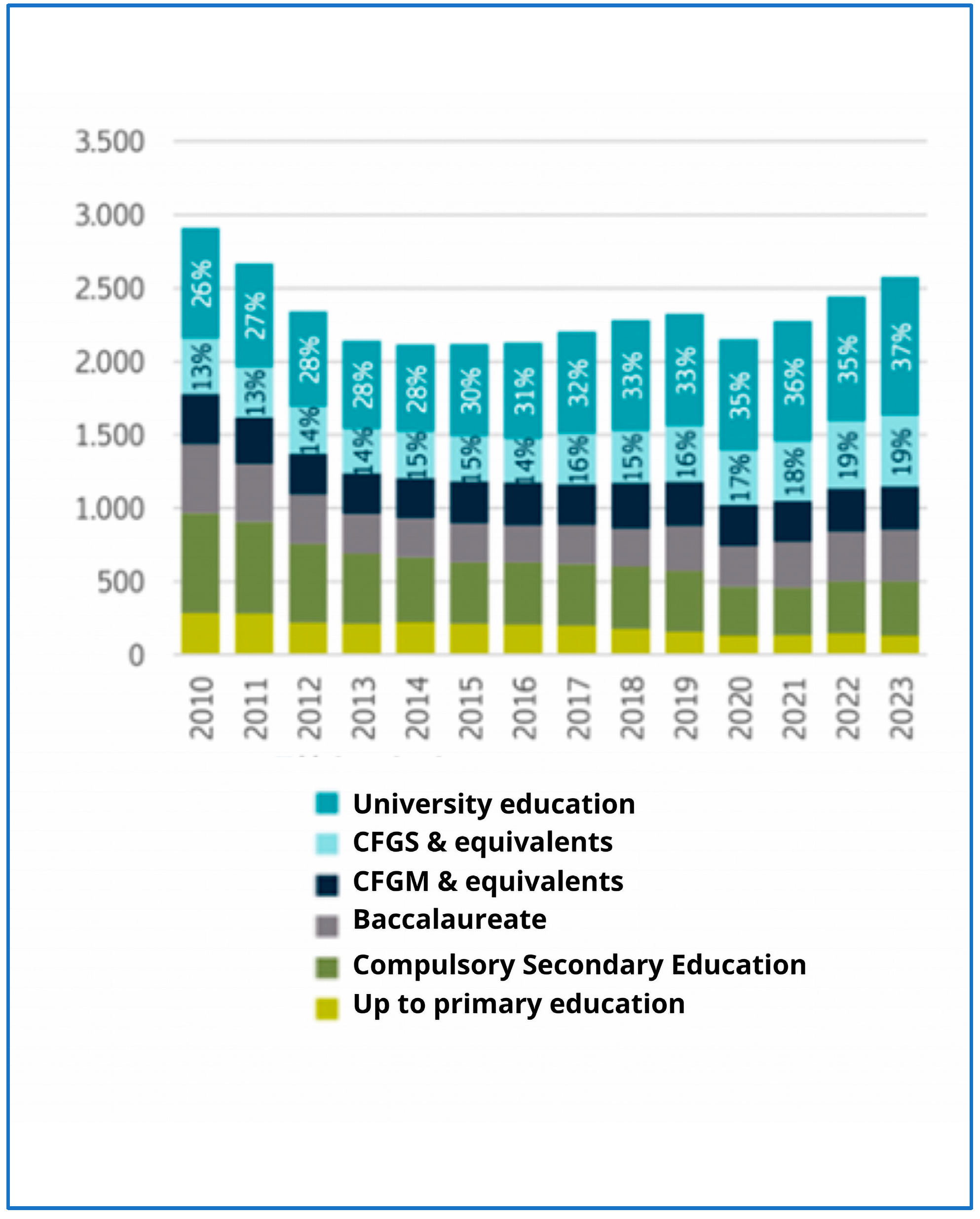

- Pérez, F., & Aldás, J. (2024). La inserción laboral de los universitarios 2013–2023. Evolución, diferencias por estudios y brechas de género. Fundación BBVA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarska, A. (2019). Cooperative relations between public higher education institutions: The contextual nature of the process of their creation. Management, 23(2), 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rando-Cueto, D., De las Heras-Pedrosa, C., & Paniagua-Rojano, F. J. (2024). Análisis sobre desinformación política en los discursos de líderes del Gobierno español vía X. Revista Latina De Comunicación Social, (83), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero Hernández, M. (2017). Propuesta de un departamento de relaciones públicas para la universidad la salle Cancún/Proposal for a department of public relations for the university la salle in Cancun. Revista Internacional de Relaciones Públicas, 13(7), 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, G., & Capriotti, P. (2024). Estrategias de publicación de los CEO de empresas de América Latina en LinkedIn y su impacto en el engagement. Revista de Comunicación, 23(2), 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Mariño, A. G., Paniagua-Rojano, F. J., & Piñeiro-Naval, V. (2020). Comunicación interactiva en sitios web universitarios de Ecuador. Revista De Comunicación, 19(1), 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., & Singh, L. B. (2017). E-learning for employability skills: Students perspective. Procedia Computer Science, 122, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Cano, E., León Urrutia, M., Parra-González, M. E., & López Meneses, E. (2020). Analysis of interpersonal competences in the use of ICT in the Spanish university context. Sustainability, 12(2), 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissers, M., Paulussen, S., & De Bruijn, G.-J. (2024). Surfing the COVID-19 news waves: A Belgian case study of science communication and public relations with university press releases. Journal of Science Communication, 23(06), A06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G. (2011). The development of university-based entrepreneurship ecosystems: Global practices. London Review of Education, 9(3), 349–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B., Bayne, S., & Shay, S. (2020). The datafication of teaching in higher education: Critical issues and perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeler, I., & Bridgen, E. (2025). Shaping the future: Discursive practices in promoting public relations education at UK universities. Journal of Communication Management, 29(1), 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Date of Search | Link to Employability and Entrepreneurship Services |

|---|---|

| University of Malaga (UMA) | https://talentank.uma.es |

| https://www.link.uma.es | |

| University of Cordoba (UCO) | https://www.uco.es/organiza/centros/cefem/index.php/fundecor |

| University of Granada (UGR) | https://ugremprendedora.ugr.es |

| https://viceinnova.ugr.es | |

| University of Seville (US) | https://alumni.us.es/servicios-alumni-us/empleabilidad-y-emprendimiento |

| https://servicio.us.es/spee/quienes-somos-contacto | |

| University of Almeria (UAL) | https://www.ual.es/emprendimiento |

| https://www.ual.es/empleo | |

| University of Huelva (UHU) | https://www.uhu.es/soipea/unpasoadelante/ |

| University of Cadiz (UCA) | https://emprendimientoyempleabilidad.uca.es |

| University of Jaen (UJA) | https://empleo.ujaen.es/taalent-y-mooc |

| Pablo de Olavide University (UPO) | https://www.upo.es/fundacion/empleabilidad-y-emprendimiento/ |

| Type of Variable | Indicators | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Content | Contact information | User registration: yes/no Email: yes/no Address: yes/no Mobile: yes/no Links of interest: yes/no Institutional newsletter: yes/no Social networks: yes/no which ones Blogs: yes/no |

| Images on the web | Facilities: yes/no Other activities or events: yes/no | |

| Organizational culture | About us: yes/no Mission and vision: yes/no | |

| Documentation | Communications/notices: yes/no Download documents: yes/no Opening hours: yes/no | |

| Services and activities | Training activities: yes/no Academic activities: yes/no University extension: yes/no | |

| Updating | Yes/no/with date, without date | |

| Appearance/usability | Rating from 1 to 10 | Contrast of colors, images, sounds, texts, graphics, quality of design, loading time, execution, and visual coherence are valued. |

| Accessibility | Very accessible | 0–10 problems |

| Fairly accessible | 11–30 problems | |

| Not very accessible | 31–90 problems | |

| Insufficiently accessible | More than 90 problems |

| University | Number of Followers | |

|---|---|---|

| University of Malaga (UMA) | https://www.linkedin.com/showcase/talentankuma/?originalSubdomain=es | 5045 |

| https://es.linkedin.com/showcase/link-by-uma---atech/ | 4612 | |

| University of Cadiz (UCA) | https://es.linkedin.com/company/ucaemprende | 1000 |

| University of Cordoba (UCO) | https://es.linkedin.com/company/fundecor | 10,000 |

| University of Granada (UGR) | https://ugremprendedora.ugr.es | 3000 |

| University of Seville (US) | https://www.linkedin.com/company/secretariado-prácticas-en-empresa-y-empleo-universidad-de-sevilla/ | 126 |

| University of Huelva (UHU) | https://www.linkedin.com/in/soipea-universidad-de-huelva-b77ba7146/recent-activity/all/ | 1274 |

| Pablo de Olavide University (UPO) | https://www.linkedin.com/company/fundacionupo/ | 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Herrería, M.; Rando-Cueto, D.; Rodríguez-Vera, A.d.P.; de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. The Role of Public Relations in the Employability and Entrepreneurship Services of Andalusian Public Universities. Journal. Media 2025, 6, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030118

Ruiz-Herrería M, Rando-Cueto D, Rodríguez-Vera AdP, de las Heras-Pedrosa C. The Role of Public Relations in the Employability and Entrepreneurship Services of Andalusian Public Universities. Journalism and Media. 2025; 6(3):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030118

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Herrería, Minea, Dolores Rando-Cueto, Ainhoa del Pino Rodríguez-Vera, and Carlos de las Heras-Pedrosa. 2025. "The Role of Public Relations in the Employability and Entrepreneurship Services of Andalusian Public Universities" Journalism and Media 6, no. 3: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030118

APA StyleRuiz-Herrería, M., Rando-Cueto, D., Rodríguez-Vera, A. d. P., & de las Heras-Pedrosa, C. (2025). The Role of Public Relations in the Employability and Entrepreneurship Services of Andalusian Public Universities. Journalism and Media, 6(3), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia6030118