Victims of a Human Tragedy or “Objects” of Migrant Smuggling? Media Framing of Greece’s Deadliest Migrant Shipwreck in Pylos’ Dark Waters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Most Frequent Indicators of Conflict and Peace Frames

Shipwreck in Pylos: “We have never before experienced such a tragedy in our country”.

Shipwreck in Pylos: The Mediterranean Sea is a “watery grave”—Around 600 migrants on board the boat that sank in international waters off Pylos.

Shipwreck in Pylos: Journey to hell with the “Mother of Martyrs”—The tragic irony of the fishing boat’s name.

“The ship is a floating graveyard”.

Unspeakable tragedy with the shipwreck in Pylos: 78 dead, 104 rescued, and fears of dozens of missing persons.

Pylos: Major migrant rescue operation—79 dead, 104 rescued.

Shipwreck in Pylos: The minute-by-minute chronicle of the tragedy—The smugglers repeatedly refused help.

Shipwreck in Pylos: The Mediterranean at the mercy of smugglers—“Turnover” of millions, a hundred deaths.

The trade of hope and the routes of death.

Migration: Death slavers, the Libya-Italy routes, and the billion-dollar dance.

Shipwreck in Pylos—Messages from Europeans: “We must put an end to the ruthless operation of smugglers”.

“The shipwreck brings to the fore once again, in the most tragic way, the need to dismantle the global human trafficking networks which place migrants’ lives in danger”, [the Migration Ministry] said.

Coast Guard: Rescued 80 migrants off Pylos, in international waters.

Migration Ministry: those rescued from the shipwreck of Pylos will be transferred to Malakasa camp […] The transport will be done under the responsibility of the ministry with hired buses. In Malakasa, preparations have already been made for their reception since yesterday as this structure had been chosen from the very beginning.

The Coast Guard knew hours before that the fishing boat was rocking dangerously.

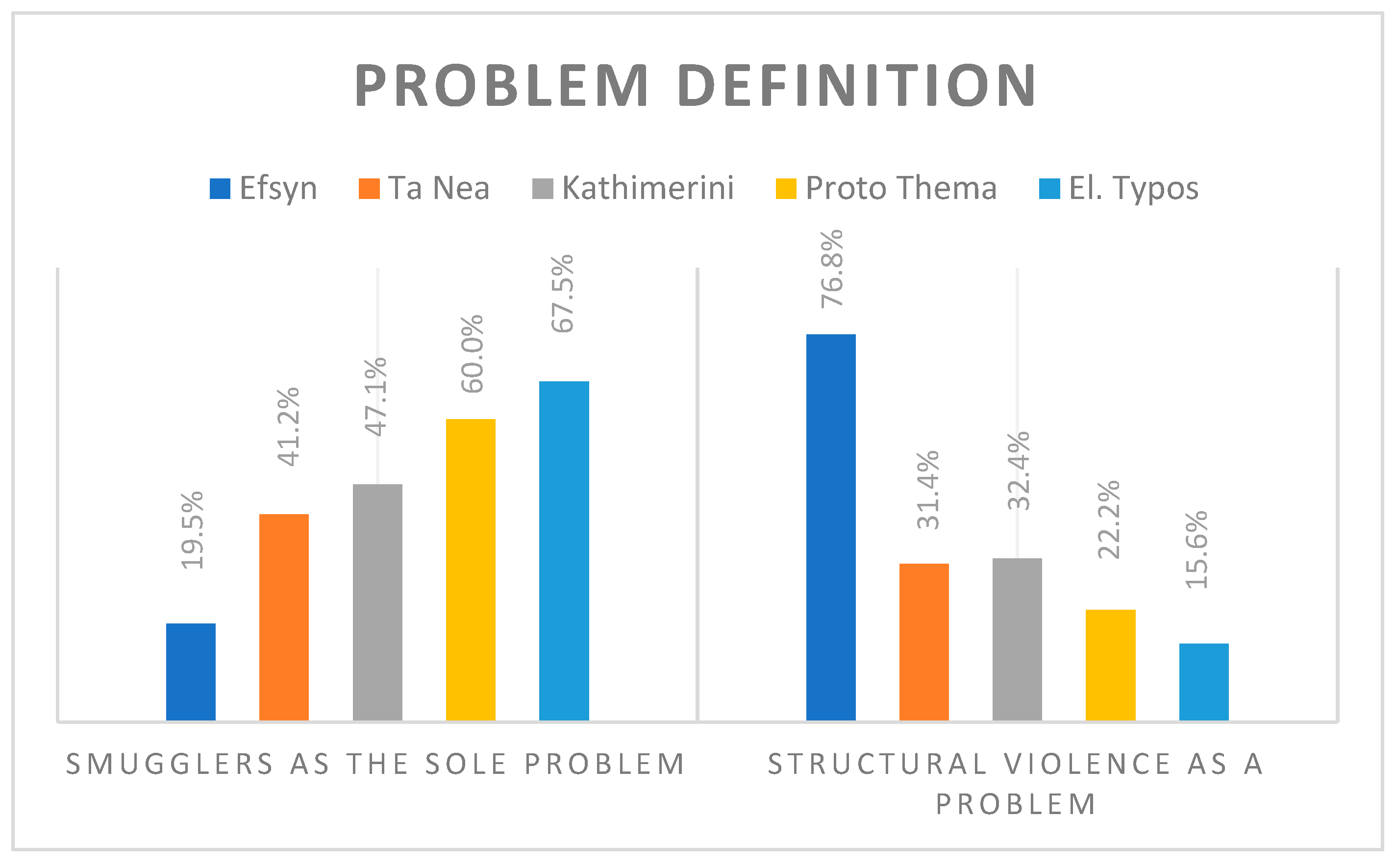

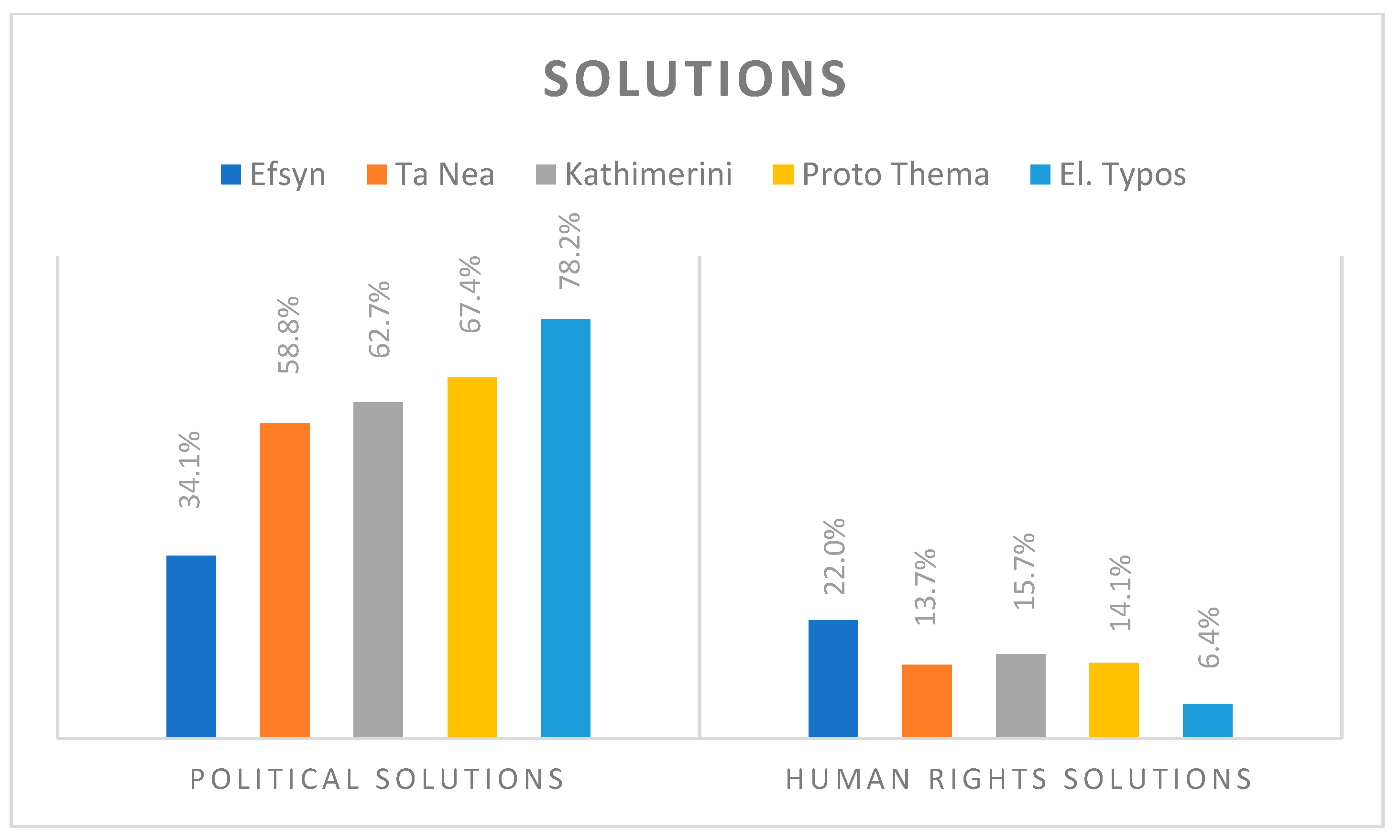

4.2. Differences and Similarities between Different Media Outlets

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acharya, Amitav. 2001. Human Security: East Versus West. International Journal 56: 442–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Yasmin. 2023. Can a Negative Representation of Refugees in Social Media Lead to Compassion Fatigue? An Analysis of the Perspectives of a Sample of Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Turkey. Journalism and Media 4: 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. Greece: Submission to the UN Committee against Torture, 73rd Session, 19 April–13 May 2022, List of Issues Prior to Reporting. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/EUR2551782022ENGLISH.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Anderson, Leticia. 2015. Countering Islamophobic Media Representations: The Potential Role of Peace Journalism. Global Media and Communication 11: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidis, Dimitris, and Christina Papastathopoulou. 2023. The Coast Guard knew hours before that the fishing boat was rocking dangerously. Efsyn. June 19. Available online: https://www.efsyn.gr/ellada/koinonia/394275_limeniko-gnorize-ores-prin-oti-alieytiko-klydonizotan-epikindyna (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Aradau, Claudia. 2004. The Perverse Politics of Four-Letter Words: Risk and pity in the Securitisation of Human Trafficking. Millennium 33: 251–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athinakis, Dimitris. 2023. The trade of hope and the routes of death. Kathimerini. June 16. Available online: https://www.kathimerini.gr/society/562472824/to-emporio-elpidas-kai-ta-dromologia-toy-thanatoy/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Benert, Vivien, and Anne Beier. 2016. Influx of Migrants versus People in Need—A Combined Analysis of Framing and Connotation in the Lampedusa News Coverage. Global Media Journal—German Edition 6. Available online: https://globalmediajournal.de/index.php/gmj/article/view/48 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Benson, Rodney. 2013. Shaping Immigration News: A French-American Comparison. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaraki, Lilie. 2006. The Spectatorship of Suffering. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaraki, Lilie, and Rafal Zaborowski. 2017. Voice and Community in the 2015 Refugee Crisis: A Content Analysis of News Coverage in Eight European Countries. International Communication Gazette 79: 613–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow-White, Peter, and Rob McMahon. 2011. News Media Encoding of Racial Reconciliation: Developing a Peace Journalism Model for the Analysis of ‘Cold’ Conflict. Media, Culture & Society 33: 989–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, Eugenio, and Flora Bell. 2021. Guilt by association? The criminalisation of sea rescue NGOs in Italian media. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47: 4285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadi, Angeliki. 2020. Refugees at the Gate of Europe. In ELIAMEP Policy Brief, Nr. 112. Athens: Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Dines, Nick, Nicola Montagna, and Vincenzo Ruggiero. 2015. Thinking Lampedusa: Border construction, the spectacle of bare life and the productivity of migrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies 38: 430–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, Rafael. 2016. Framing discourse during the Lampedusa crisis: Victims and intruders in the Spanish press. In Political Communication in Times of Crisis. Edited by Oscar G. Luengo. Berlin: Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Eberl, Jakob-Moritz, Christine Meltzer, Tobias Heidenreich, Beatrice Herrero, Nora Theorin, Fabienne Lind, Rosa Berganza, Hajo Boomgaarden, Christian Schemer, and Jesper Strömbäck. 2018. The European Media Discourse on Immigration and Its Effects: A Literature Review. Annals of the International Communication Association 42: 207–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECRE. Greece: Systematic Pushbacks Continue by Sea and Land as MEPs Demand EU Action, Deaths Up Proportionate to Arrivals, Number of People in Reception System Reduced by Half–Mitarachi Still Not Satisfied. Available online: https://ecre.org/greece-systematic-pushbacks-continue-by-sea-and-land-as-meps-demand-eu-action-deaths-up-proportionate-to-arrivals-number-of-people-in-reception-system-reduced-by-half-mitarachi-still-not/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Eleftheros Typos. 2023a. Migration Ministry: Those Rescued from the Shipwreck of Pylos Will Be Transferred to Malakasa Camp. June 15. Available online: https://eleftherostypos.gr/ellada/yp-metanastefsis-sti-malakasa-tha-metaferthoun-oi-diasothentes-apo-to-navagio-tis-pylou (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Eleftheros Typos. 2023b. Shipwreck in Pylos: Journey to Hell with the “Mother of Martyrs”—The Tragic irony of the Fishing Boat’s Name. June 16. Available online: https://eleftherostypos.gr/ellada/navagio-stin-pylo-taxidi-stin-kolasi-me-tin-mitera-ton-martyron-i-tragiki-eironeia-me-tin-onomasia-tou-alieftikou-vinteo (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Entman, Robert. 1993. Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication 43: 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esses, Victoria, Stelian Medianu, and Andrea Lawson. 2013. Uncertainty, Threat, and the Role of the Media in Promoting the Dehumanization of Immigrants and Refugees. Journal of Social Issues 69: 518–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franquet Dos Santos Silva, Miguel, Svein Brurås, and Ana Beriain. 2018. Improper Distance: The Refugee Crisis Presented by Two Newsrooms. Journal of Refugee Studies 31: 507–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galtung, Johan. 1998. High Road, Low Road–Charting the Course for Peace Journalism (Cape Town: Centre for Conflict Resolution). Track Two 7. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC111753 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Galtung, Johan. 2006. Peace Journalism as an Ethical Challenge. GMJ: Mediterranean Edition 1: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Galtung, Johan, and Mari Holmboe Ruge. 1965. The Structure of Foreign News: The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers. Journal of Peace Research 2: 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamson, William, and Andrew Modigliani. 1987. The Changing Culture of Affirmative Action. Research in Political Sociology 3: 137–77. [Google Scholar]

- Giubilaro, Chiara. 2018. (Un)framing Lampedusa: Regimes of Visibility and the Politics of Affect in Italian Media Representations. In Border Lampedusa. Edited by Gabriele Proglio and Laura Odasso. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliani, Gaia. 2016. The Mediterranean as a Stage: Borders, Memories, Bodies. In Decolonising the Mediterranean: European Colonial Heritages in North Africa and the Middle East. Edited by Gabriele Proglio. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10316/34189 (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Gregoriou, Christiana, Ilse Ras, and Nina Muždeka. 2022. “Journey into hell [… where] migrants froze to death”; a critical stylistic analysis of European newspapers’ first response to the 2019 Essex Lorry deaths. Trends in Organized Crime 25: 318–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greussing, Esther, and Hajo Boomgaarden. 2017. Shifting the refugee narrative? An automated frame analysis of Europe’s 2015 refugee crisis. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43: 1749–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, Alexandria. 2010. When the Threatened Become the Threat: The Construction of Asylum Seekers in British Media Narratives. International Relations 24: 456–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfeli, N. 2020. From “Illegals” to “Unfortunates”: News Framing of Immigration and the “Refugee Crisis” in Crisis-Stricken Greece. In The Emerald Handbook of Digital Media in Greece (Digital Activism and Society: Politics, Economy And Culture in Network Communication). Edited by A. Veneti and A. Karatzogianni. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 369–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kalfeli, N., C. Angeli, A. Gardikiotis, and C. Frangonikolopoulos. 2023. Between two crises: News framing of migration during the greek-turkish border crisis and covid-19 in Greece. Journalism Studies 24: 226–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfeli, N., C. Frangonikolopoulos, and A. Gardikiotis. 2022. Expanding Peace Journalism: A new Model for Analyzing Media Representations of Immigration. Journalism 23: 1789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathimerini. 2023a. Migration Ministry for the Shipwreck in Pylos: Task Forces Assist with All Means. June 14. Available online: https://www.kathimerini.gr/politics/562470625/yp-metanasteysis-gia-to-nayagio-stin-pylo-klimakia-syndramoyn-me-ola-ta-mesa/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Kathimerini. 2023b. Shipwreck in Pylos: “We Have Never before Experienced Such a Tragedy in Our Country”. June 14. Available online: https://www.kathimerini.gr/society/562470988/dimarchos-kalamatas-stin-k-ga-to-nayagio-den-echoyme-xanazisei-tetoia-tragodia/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Kim, Sei-Hill, John Carvalho, Andrew Davis, and Amanda Mullins. 2011. The View of the Border: News Framing of the Definition, Causes, and Solutions to Illegal Immigration. Mass Communication and Society 14: 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Seow Ting, and Crispin Maslog. 2005. War or Peace Journalism? Asian Newspaper Coverage of Conflicts. Journal of Communication 55: 311–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léonard, Sarah, and Christian Kaunert. 2020. The Securitisation of Migration in the European Union: Frontex and its Evolving Security Practices. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 1417–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Jake, and Annabel McGoldrick. 2005. Peace Journalism. Gloucestershire: Hawthorn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, Paolo, Marco Mazzoni, Giovanni Barbieri, Marco Damiani, and Matteo Gerli. 2021. What shapes the coverage of immigration. Journalism 22: 845–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagut, Marta, and Carlota Moragas-Fernández. 2020. The European Refugee Crisis Discourse in the Spanish Press: Mapping Humanization and Dehumanization Frames Through Metaphors. International Journal of Communication 14: 69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Lax, Violeta. 2018. The EU humanitarian border and the securitization of human rights: The ‘rescue-through-interdiction/rescue-without-protection’paradigm. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 56: 119–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, Kimberly. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, Samuel, Sophie Bennett, Chyna Mae Cobden, and Deborah Earnshaw. 2022. ‘It’s time we invested in stronger borders’: Media representations of refugees crossing the English Channel by boat. Critical Discourse Studies 19: 348–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, Scott, Jennifer Hoewe, Minghui Fan, and Keith Huffman. 2019. Portrayals of Immigrants and Refugees in U.S. News Media: Visual Framing and Its Effect on Emotions and Attitudes. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 63: 677–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politi, Filia. 2023. Shipwreck in Pylos: “The ship is a floating graveyard”. Ta Nea. June 17. Available online: https://www.tanea.gr/2023/06/17/greece/nayagio-stin-pylo-ploto-nekrotafeio-to-ploio/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Proto Thema. 2023a. Coast Guard: Rescued 80 Migrants off Pylos, in International Waters. June 14. Available online: https://www.protothema.gr/greece/article/1381660/limeniko-epiheirisi-diasosis-metanaston-anoihta-tis-pulou-se-diethni-udata/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Proto Thema. 2023b. Pylos: Major Migrant Rescue Operation—79 Dead, 104 Rescued. June 14. Available online: https://www.protothema.gr/greece/article/1381835/pulos-megali-epiheirisi-diasosis-metanaston-79-oi-nekroi-104-oi-diasothedes/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Proto Thema. 2023c. Shipwreck in Pylos—Messages from Europeans: ‘We Must Put an End to the Ruthless Operation of Smugglers’. June 14. Available online: https://www.protothema.gr/greece/article/1381958/nauagio-stin-pulo-minumata-europaion-prepei-na-valoume-ena-telos-stin-adistakti-epiheirisi-ton-diakiniton/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Proto Thema. 2023d. Shipwreck in Pylos: The Mediterranean Sea Is a “Watery Grave”—Around 600 Migrants on Board the Boat That Sank in International Waters Off Pylos. June 14. Available online: https://www.protothema.gr/greece/article/1381947/nauagio-stin-pulo-ugros-tafos-i-mesogeios-gia-ekatodades-metanastes-peripou-600-atoma-epevainan-sto-skafos/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Proto Thema. 2023e. Shipwreck in Pylos: The Minute-by-Minute Chronicle of the Tragedy—The Smugglers Repeatedly Refused Help. June 14. Available online: https://www.protothema.gr/greece/article/1382021/nauagio-stin-pulo-lepto-pros-lepto-i-tragodia-me-tous-79-nekrous-den-theloume-tipota-elegan-epaneilimmenos/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Sadana, Georgia. 2023. Shipwreck in Pylos: The Mediterranean at the Mercy of Smugglers—“Turnover” of Millions, a Hundred Deaths. Proto Thema. June 15. Available online: https://www.protothema.gr/greece/article/1382080/nauagio-stin-pulo-i-mesogeios-ermaio-ton-lathrodiakiniton-tziroi-ekatommurion-ekatomvi-nekron/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Shaw, Ibrahim Seaga, Jake Lynch, and Robert Hackett. 2011. Expanding Peace Journalism: Comparative and Critical Approaches. Sydney: Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stepka, Maciej. 2018. Humanitarian Securitization of the 2015 ‘Migration Crisis’. Investigating Humanitarianism and Security in the EU Policy Frames on Operational Involvement in the Mediterranean. In Migration Policy in Crisis. Edited by Ibrahim Sirkeci, Emilia Lana de Freitas Castro and Ulku Sezgi Sozen. London: Transnational Press, pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Orozco, Marcelo, Vivian Louie, and Roberto Suro. 2011. Writing Immigration: Scholars and Journalists in Dialogue. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ta Nea. 2023. Unspeakable Tragedy with the Shipwreck in Pylos: 78 Dead, 104 Rescued and Fears of Dozens of Missing Persons. June 14. Available online: https://www.tanea.gr/2023/06/14/greece/aneipoti-tragodia-me-to-nayagio-stin-pylo-32-nekroi-104-diasothentes-kai-fovoi-gia-dekades-agnooumenous/ (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Thorbjornsrud, Kjersti. 2015. Framing Irregular Immigration in Western Media. American Behavioral Scientist 59: 771–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorbjornsrud, Kjersti, and Ustad Figenschou. 2016. Do Marginalised Sources Matter? A Comparative Analysis of Irregular Migrant Voice in Western Media. Journalism Studies 17: 337–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tivona, Elissa. 2011. Globalisation of Compassion: Women’s Narratives as Models for Peace Journalism. In Expanding Peace Journalism: Comparative and Critical Approaches. Edited by Jake Lynch, Ibrahim Seaga and Robert Hackett. Sydney: Sydney University Press, pp. 317–44. [Google Scholar]

- Vamvaka, Anastasia. 2023. Migration: Death Slavers, the Libya—Italy Routes and the Billion—Dollar Dance. Eleftheros Typos. June 18. Available online: https://eleftherostypos.gr/ellada/metanasteftiko-oi-douleboroi-tou-thanatou-ta-dromologia-livyi-italia-kai-o-choros-disekatommyrion (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Van Gorp, Baldwin. 2005. Where Is the Frame? Victims and Intruders in the Belgian Press Coverage of the Asylum Issue. European Journal of Communication 20: 484–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verleyen, Emmi, and Kathleen Beckers. 2023. European Refugee Crisis or European Migration Crisis? How Words Matter in the News Framing (2015–2020) of Asylum Seekers, Refugees, and Migrants. Journalism and Media 4: 727–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, Scott. 2011. The ‘human’ as referent object? Humanitarianism as securitization. Security Dialogue 42: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youngblood, Steven. 2017. Peace Journalism Principles and Practices: Responsibly Reporting Conflicts, Reconciliation and Solutions. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yücel, Alev. 2021. Symbolic annihilation of Syrian refugees by Turkish news media during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal for Equity in Health 20: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerback, Thomas, Carsten Reinemann, Peter Van Aelst, and Andrea Masini. 2020. Was Lampedusa a key Event for Immigration News? An Analysis of the Effects of the Lampedusa Disaster on Immigration Coverage in Germany, Belgium, and Italy. Journalism Studies 21: 748–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Conflict Frame | Peace Frame |

|---|---|

| 1.Official sources | 7. Multi-party orientation |

| 2. Refugees and migrants as a threat or as a victim | 8. Focus on human stories |

| 3. Refugees and migrants as numbers and as statistics | 9. Refugee/migrant voice |

| 4. Emotive language | 10. Non-emotive language |

| 5. Smugglers as the sole problem | 11. Structural violence as a problem |

| 6. Political solutions | 12. Human rights solutions |

| Conflict Frame Indicators | Frequency of Appearance (% of Appearance in the News Stories) |

|---|---|

| 380 (85%) |

As a victim | 393 (88%) 7 (1.6%) 386 (86.4%) |

| 351 (78.5%) |

| 342 (76.5%) |

| 274 (61.3%) |

| 218 (48.8%) |

| Peace Frame Indicators | |

| 154 (34.5%) |

| 105 (23.5%) |

| 103 (23%) |

| 79 (17.7%) |

| 67 (15%) |

| 65 (14.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalfeli, P.; Angeli, C.; Frangonikolopoulos, C. Victims of a Human Tragedy or “Objects” of Migrant Smuggling? Media Framing of Greece’s Deadliest Migrant Shipwreck in Pylos’ Dark Waters. Journal. Media 2024, 5, 537-551. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020036

Kalfeli P, Angeli C, Frangonikolopoulos C. Victims of a Human Tragedy or “Objects” of Migrant Smuggling? Media Framing of Greece’s Deadliest Migrant Shipwreck in Pylos’ Dark Waters. Journalism and Media. 2024; 5(2):537-551. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalfeli, Panagiota (Naya), Christina Angeli, and Christos Frangonikolopoulos. 2024. "Victims of a Human Tragedy or “Objects” of Migrant Smuggling? Media Framing of Greece’s Deadliest Migrant Shipwreck in Pylos’ Dark Waters" Journalism and Media 5, no. 2: 537-551. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020036

APA StyleKalfeli, P., Angeli, C., & Frangonikolopoulos, C. (2024). Victims of a Human Tragedy or “Objects” of Migrant Smuggling? Media Framing of Greece’s Deadliest Migrant Shipwreck in Pylos’ Dark Waters. Journalism and Media, 5(2), 537-551. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia5020036