Abstract

Using a discourse approach, this study examines online news and opinion pieces about calls for the British Museum to return Chinese artefacts. We examine the interpersonal meanings conveyed by the linguistic choices made in these texts. This study uses the appraisal system in the systemic functional linguistic (SFL) framework to examine how news discourse addresses the issue and constructs interpersonal meanings. Graduation resources, as a subcategory of appraisal system, can underpin the degree of meanings and perspectives, allowing writers to adjust the gradability of attitudinal meanings conveyed to readers. This research first examines how the writer’s voice is embedded in graduation resources, and later, how these graduation resources are used in online news articles calling for the return of the artefacts. This study also examines how online newspapers covered a short film by vloggers called “Escape from the British Museum”, which sparked massive social media reactions, offering new perspectives on how social media and traditional news organisations interact to construct meanings through language. The results show that quantification and fulfilment (completion) resources are the two most common subcategories of graduation resources. The findings shed light on the language strategies used in news and social media discourse, as well as the interpersonal meanings behind such requests for cultural heritage repatriation.

1. Introduction

Global attention has been drawn to the return of cultural artefacts to their original countries. Debates abound regarding the ownership of artefacts, particularly those taken from colonial-era conquered territories (Abungu 2022). The British Museum, which holds a substantial collection of artefacts, is one of the most well-known museums being criticized in the discussion of cultural heritage repatriation (Godwin 2020; Fincham 2012). Duthie (2011) explores the controversy of the British Museum in the context of classical heritage. Despite considerable pressure from foreign governments, the museum has consistently refused to return various countries’ relics and antiquities acquired during imperial acquisition (Duthie 2011). The British Museum houses approximately 23,000 Chinese artefacts, such as bronzes, paintings, and jade, highlighting China’s rich cultural heritage (Zhong 2017). However, reports of lost, stolen, or damaged items have heightened requests for repatriation in the last few decades (Fine-Dare 2002; Harding 1996; Merryman 1985). The global call for the return of these artefacts has sparked debate on social media (GT Staff Reporters 2023). Different linguistic choices are being used to communicate, convey meanings, and persuade others. The short film “Escape from the British Museum” by Chinese vloggers, nicknamed Pancake Fruit and Summer Sister, on 27 August 2023, which depicts the journey of a jade teapot being returned to China, has sparked many discussions on news and social media platforms (Hawkins 2023; Sin 2023). It is evident that language plays a significant role in shaping the attitudes and opinions of writers (Garrett 2010). This study examines the attitudinal meanings used in the discourse of opinion and news articles in seven English-language newspapers in China, the United Kingdom, and Singapore regarding demands for the return of Chinese artefacts from the British Museum. We hope to uncover the linguistic features used to embed the authorial voice and reveal the negotiations that underpin such requests by analysing texts from news discourse. Systemic functional linguistics (SFL) is a theory of language that focuses on the relationship between language and social context (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). The appraisal system, developed within SFL theory, allows for the analysis of evaluative language in texts (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014; Martin and White 2005). The system is particularly useful in identifying how language users communicate their opinions and feelings about different topics, people, and events. By analysing the appraisal choices made by writers, one can gain insight into the writers’ perspectives (White 2009, 2012). Therefore, the appraisal system was practical when examining news articles and opinion pieces in the present study, as these texts often contain evaluative language that shapes their overall meaning. Appraisal resources generally contribute to the interpersonal metafunction of SFL and are concerned with identifying attitudinal meanings in texts (Martin and White 2005). The three subsystems of the appraisal system are graduation, engagement, and attitude (Martin and White 2005). Graduation is used to adjust the degree or intensity of evaluative language in a text, and it is represented by the two subtypes of force and focus (Martin and White 2005). The present study examines how online news articles use graduation resources to reinforce the focus and force in conveying the writer’s voice, as well as the frequency patterns in the use of graduation resources in the data. In addition, the way in which news writers reported on the social media vloggers’ film caught our attention. In order to investigate how linguistic choices convey the writer’s voice and possibly influence cultural sentiments, the present study has three research questions:

- How do online news articles use graduation resources to embed the writer’s voice in calls for the British Museum to return Chinese artefacts?

- What frequency patterns emerge in online newspapers’ use of graduation resources in reporting calls for the return of artefacts?

- How do different online newspapers report on the short film “Escape from the British Museum” and netizens’ reactions on social media?

2. Literature Review

Systemic functional linguistics (SFL) provides a comprehensive framework for analysing language in its social context, and it views language as a social semiotic system (Halliday and Matthiessen 2014). It emphasizes the interaction between language, social function, and context. Language choices are influenced by the social context and serve specific communicative functions (Martin and Rose 2007). According to Halliday and Matthiessen (2014), SFL focuses on the three metafunctions of ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings. We explored the interpersonal meanings that abound in the debate over the ownership of Chinese artefacts by the British Museum, which are abundant in news texts (see GT Staff Reporters 2023; Hongyu 2023; Wang and Cai 2023; Wei 2023). The SFL framework helps us to explore how attitudinal meanings are constructed towards cultural heritage repatriation. The appraisal system provides a systematic method for analysing attitudinal meanings in texts in terms of attitude, graduation, and engagement (Martin and White 2005). The appraisal system has been used to identify writers’ evaluative stances and persuasive strategies; for example, Bednarek and Caple (2010) used a social semiotic framework and appraisal system to examine environmental reporting in a broadsheet newspaper in Australia. They analysed a corpus of 40 stories for evaluative meanings in headlines, images, and captions and interpreted their findings in terms of discourse analysis. Abasi and Akbari (2013) used the appraisal system to study dissent in news discourse during the Iranian presidential election debates, focusing on how the candidates were evaluated in the news media. By shifting from a journalistic to a linguistic discourse approach, Sabao (2016) showed that the linguistic discourse analytical framework of appraisal analysis provides a different approach to examining objectivity and ideological bias in hard news coverage. According to Jin’s (2019) study of the New York Times report on China–DPRK relations, most attitudinal resources with negative effects are realized through lexical and semantic strategies. In the present study, phrases such as “cultural collaboration (appraisal item quoted from text 6 in the data)” may construct an invoked attitude that supports the British Museum’s contribution, whereas terms such as having “historical sins (appraisal item quoted from text 6 in the data)” may be interpreted as a criticism. Understanding these evaluative language choices allows us to better understand the underlying attitudes and beliefs of the writers. Furthermore, the use of modal verbs such as “should” or “have to” can indicate obligation or necessity. These modal verbs can express a repatriation stance, indicating whether the writers appear to support or oppose the return of Chinese artefacts to their country of origin.

Gradability is a feature of the engagement system and a shared property of attitude resources (Martin and White 2005). Writers can use graduation resources to grade up or down their positive or negative attitudinal meanings, and this can be separated into two subcategories: force and focus (Martin and Rose 2007). Writers can adjust force resources to enhance or lighten the impact of their utterances (Martin and White 2005; White 2003). Adverbial intensifications such as “slightly” and “really” are examples of force, as are quantifications such as numbers, mass, and extent (Martin and White 2005, p. 137). On the other hand, the focus of writers’ semantic categorisations can be blurred or sharpened (Martin and White 2005). Focus can be sharpened by using words such as “exact” and “real”, or it can be blurred by using hedging and vague language such as “kind of” and “sort of” (White 2008). Martin and White (2005) began their discussion of graduation within an appraisal analysis by emphasizing the importance of engagement. Graduation was later linked to attitude by Hood (2006) and Hood and Forey (2008), stating as part of their call centre language study that graduation resources conveyed the experiential meanings of the participants. For example, a customer said, “I have talked to 12 people”, where “12 people” is a lexicogrammatical feature that expresses interpersonal meaning in the negotiation process of a complex service call. This expression alone does not carry an evaluative charge but has semantic meanings that are classified as a negative normality of judgment in the context of complaint calls (Hood and Forey 2008, p. 402). An analysis of interpersonal meanings in professional discourse can provide insights into the dynamics of complex service calls, including negotiation processes and communication patterns (also see Wan 2017, 2023a, 2023b). Hood (2006) broadened the scope of focus to include propositional and process meanings. Realization (e.g., “just possible that” and “very likely that”) and completion (e.g., “I tried to do this task.”) are subcategories of fulfilment (Hood 2006). The present study takes Hood and Forey’s (2008, p. 395) detailed framework for analysing graduation as a starting point and then applies it to the attitudinal meaning of the collected texts.

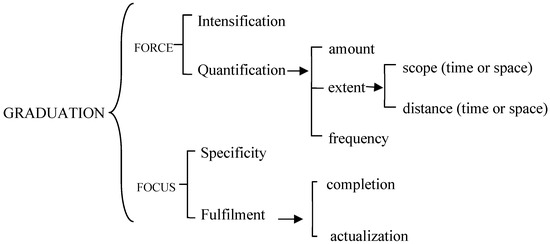

Hood and Forey’s (2008, p. 395) graduation network is shown in Figure 1. Quantity can be graded in terms of the domain of force as the amount (e.g., “many times”), extent in time (e.g., “almost a month”), distance in time (e.g., “within 24 h”), and frequency (e.g., “very often”) (Hood and Forey 2008, p. 395). Focus involves grading the degree of actualization of a proposition (e.g., “it’s probably” there; does it “normally” take a week; “actually”), the degree of fulfilment of a process (e.g., “trying to reach”), and the degree of specificity surrounding an entity (e.g., I spoke with “somebody...whoever”) (Hood and Forey 2008, p. 395). The appraisal system is used to evaluate interpersonal meanings in texts (Martin and Rose 2007; Martin and White 2005). Graduation, attitude, and engagement are features that combine to construct interpersonal meanings. Understanding how different lexicogrammatical features are used to realize attitudes is important in discourse analysis. The present study aims to contribute to the understanding of how graduation resources are used to adjust writers’ attitudes in news discourse.

Figure 1.

Network of graduation (adopted from Hood and Forey 2008, p. 395).

3. Materials and Methods

Our study focused on a small corpus of seven online English newspaper articles that discussed the calls to the British Museum for the return of Chinese cultural artefacts (see Table 1). The dataset included articles from representative national news outlets such as China Daily, Global Times, People’s Daily Online, South China Morning Post, BBC, The Guardian, and Straits Times. Most of the texts were from China and Southeast Asia, including Singapore, with two articles originating from the United Kingdom. Three of the articles were opinion pieces, while the remaining four were news articles. These news articles were published in the weeks immediately following the release of the film “Escape from British Museum” on social media on 30 August 2023. These news texts were collected from news media websites using specific search terms related to the request for the British Museum to return the Chinese artefacts. The data spanned a three-week period, from 29 August to 20 September 2023, to ensure that timely and current perspectives and opinions were reflected. The written data totalled 5787 words, with an average of 827 words per article.

Table 1.

Summary of the data.

To comprehend the attitudinal meanings conveyed in the selected texts, we examined various linguistic lexicogrammatical features, including the use of numbers, adjectives, and adverbs that expressed intensity or evaluation. We manually identified and counted graduation items within the texts, focusing on the resources of force and focus and their frequency patterns. Due to the small sample size, generalisations about this museum topic should be made with caution. However, we believe that these texts are valuable because they provide an insight into the immediate reaction of news organisations to the vloggers’ film, which also relates to the ensuing debate about the artefact issue on social media.

4. Findings and Discussion

This section examines the linguistic strategies used by the news media to convey their attitudes and strengthen arguments regarding repatriation requests. The selected examples consist of positive and negative evaluations of the requests, judgments, and appreciations expressed through lexical choices, grammatical structures, and distribution patterns in the texts. Section 4.1 examines the graduation resources identified in the news discourse on repatriation requests; Section 4.2 counts the frequency and illustrates examples of each graduation subcategory; and Section 4.3 examines how online news articles have reported on the vloggers’ short film “Escape from the British Museum”.

4.1. Graduation Analysis of Returning Artefacts in News Articles

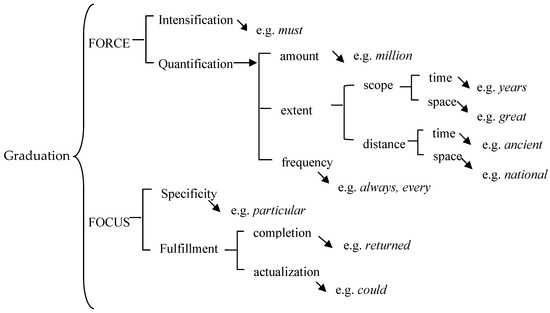

The first research question (RQ1) seeks to understand how online news articles use graduation resources to embed and emphasize the writer’s voice about the call for the British Museum to return Chinese artefacts. Graduation resources with varying degrees of intensity reflect the intensity of meanings. Hood (2006) and Hood and Forey (2008) classified these as “Intensification” (force), “Quantification” (force), “Specificity” (focus), and “Fulfilment” (focus). Hood’s framework was modified and used to create the graduation system network used in this study. Figure 2 shows the data-driven examples of graduation used in the present study.

Figure 2.

Network of graduation in news discourse (adopted from Hood and Forey 2008, p. 395).

As discussed, graduation resources are used to both intensify and weaken attitudes. The system of force is divided into two main subcategories in Figure 2: intensification and quantification. Intensification can be achieved through the use of lexicogrammatical elements such as “must”, “need to”, and “most”. There are three subsystems in the quantification system: amount, extent, and frequency. Extent is defined by Hood and Forey (2008) as the amount of time and distance in time or space. Some lexicogrammatical items that represent the scope of time are “year(s)”, “month(s)”, and “week(s)”. Distance is measured in time or space from the present moment, whereas scope refers to a period of time (Hood and Forey 2008). The last subcategory of quantification is frequency. Table 2 provides a brief illustration of each subcategory with selected examples. For the graduation analysis, all examples of appraisal in the original news articles are quoted and shown in bold.

Table 2.

Selected example for the graduation analysis of force and focus.

In news articles, modal expressions such as “must” and “have to” are used to convey the degree of certainty or obligation surrounding an issue. The hashtag “British Museum must return Chinese cultural relics for free” in Text 1 had garnered over a billion views on social media at the time of publication. The modal adjunct “must” was used by the netizens and quoted by the news writer of Text 1 to emphasize the desire for certainty regarding the return of Chinese cultural relics. The hashtag quote is an engagement item that represents the heteroglossic voice in the appraisal system (Martin and White 2005). Quantification is often used to imbue the writer’s voice with force. It is estimated that “China has lost approximately 15 million artefacts, with 10% being illegally smuggled abroad” (Text 1). The figure “million” indicates the seriousness of the situation and gives the reader an idea of how much art was stolen and illegally smuggled overseas. Next, “particularly” is a focus resource that focuses on the victimised nations from which the artefacts in Text 1 were forcibly taken.

This focus resource, “particularly”, aids in drawing the reader’s attention on the countries that have made this demand. Finally, the news reports use the perfect or past tense to address the issue of the artefacts’ return. For example, “in recent years, more lost Chinese artefacts have returned home, thanks to the persistent efforts of various parties” (Text 3). The graduation resources in the articles highlight the desired and successful outcomes of returning artefacts to their rightful owners as a result of the efforts of various parties, and the writer’s position encourages readers to support these desires. By reinforcing the writer’s attitude in these articles, the graduation resources of force and focus may engage readers and appear to attempt to elicit their emotional responses. These linguistic choices tend to position readers within the discourse and encourage them to consider the implications of artefact ownership. The following section provides more detailed illustrations and describes the distribution patterns of the subcategories of intensification (force), quantification (force), specificity (focus), and fulfilment (focus).

4.2. Frequency Patterns of Graduation Resources in Artefacts’ Return

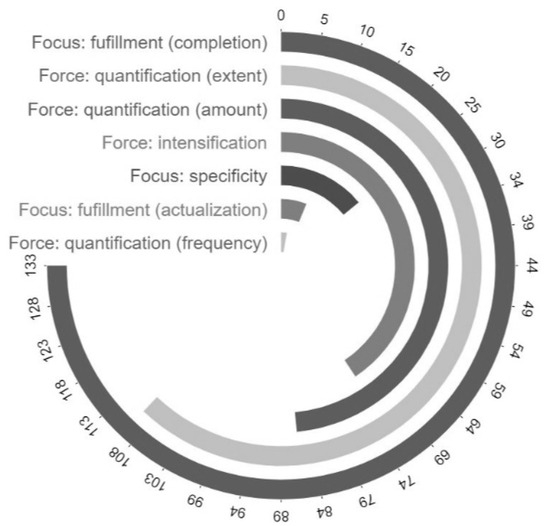

The second research question (RQ2) examines the graduation resources and the frequency patterns of their subcategories in online news and opinion pieces surrounding the artefacts’ return. Here, we continue to examine the force (i.e., intensification and quantification) and focus (i.e., specificity and fulfilment) employed by writers in order to provide some insights into how graduation and attitude resources are encoded when addressing the issue of the artefacts’ return. In this section, Table 3 first provides a summary of all examples of each graduation subtype, along with their respective frequencies and percentages. In addition, Figure 3 highlights the most common types of graduation, allowing for a visual comparison of the frequency between the different subtypes. In order to delve deeper into the attitudinal meanings conveyed in relation to the context, we selectively extracted representative examples of the most common types of graduation resources from the texts.

Table 3.

A comprehensive list of focus and force graduation resources.

Figure 3.

Frequency of intensification, quantification, specificity, and fulfilment.

The data analysis shows that all the texts examined contain graduation tokens. A total of 440 graduation tokens were identified across the corpus. Notably, 45% of these tokens are associated with force (quantification), while 30% of the tokens are associated with focus (fulfilment). The overall frequency patterns of fulfilment, specificity, intensification, and quantification are visualized in Figure 3, which shows their frequency distributions. The most common quantification categories are quantification (extent and amount), intensification in the force domain, and fulfilment (completion) in the focus domain.

The quantification subtype is the most common category. By using time scope resources to reflect historical status, the quantification (extent) resource was used in extract (1) to emphasize that the British Museum has a long history of “over 270 years”. The museum’s exhibition arrangements and methods of cultural preservation of these “ancient” Chinese objects help to show “China’s long history” in extracts (2) and (3).

(1) “Riddled with security lapses and suspected of internal theft, the British Museum, with a history spanning over 270 years, has shocked public opinion not only domestically but also internationally.”(Text 2)

(2) “…its catalogue of 23,000 items from China, ranging from ancient bronzes and jades to paintings and ceramics, has been in a controversy of challenged ownership.”(Text 2)

(3) “The museum believes that displaying objects from China alongside cultural material from other parts of the world helps people understand China’s long history better.”(Text 6)

News articles often use a variety of spatial contrasts, such as the expansive terms “huge”, “world”, “wide”, and the contracting term “only”, to emphasize the scope of the issue and enhance readers’ interest. For instance, in extracts (4) and (5), we read how the British Museum has created its “wide” and “huge collection” of “human civilization”, while we learn that China is not the “only country” deprived of cultural artefacts in extract (6).

(4) “The theft scandal has triggered a broader debate about how the British Museum amassed its huge collection in the first place, and whether it should return objects to the countries they came from.”(Text 4)

(5) “The British Museum is one of the world’s largest and best-known museums, housing 8 million artefacts from all over the world that represent a wide swathe of human civilization.”(Text 4)

(6) “China was not the only country to suffer from the looting of cultural relics.”(Text 2)

In extracts (7, 8), the quantity of lost cultural artefacts is described with graduation resources using the tokens of “many” and “a large scale”. For example, it is perceived as difficult to locate missing objects because “many” of them have not been recorded, and there is still no plan to return them on “a large scale”. As a result, “multiple” countries, as described in extract (9), including Nigeria, Greece, and Egypt, have protested and demanded the return of the objects. In describing the missing objects, these quantitative resources help to give the reader an estimate of the approximate quantity, in numbers.

(7) “Many of the missing items may be untraceable due to the fact that they were not properly catalogued.”(Text 4)

(8) “But as many have observed, the intention to return the looted and stolen treasures on a large scale is still lacking in the former colonial powers.”(Text 1)

(9) “Multiple nations have staged protests, demanding for the return of their national treasures, notable among them being Nigeria, Greece, and Egypt.”(Text 2)

The intensification of resources can be seen in the use of tokens such as “power”, “law”, and “legal” in the data. Supporters emphasize the cultural significance of these artefacts and their rightful ownership by China. They use words such as “heritage” and “human civilization” to emphasize the cultural value of these artefacts and to legitimize China’s claim to their return. In extract (10), violent means such as “colonial power” are used to construct national identity and imply historical justice.

(10) “The demands for the museums in Western countries to return the plundered artefacts have intensified in recent years, and some former colonial powers, thanks partly to the efforts of French President Emmanuel Macron, are mulling returning some of the looted and stolen treasures to their countries of origin.”(Text 1)

Some news articles frame the issue in terms of legitimate ownership in an attempt to bargain and negotiate. They emphasize the importance of legal structures and museum exhibits in preserving and promoting cultural heritage. However, opponents often use phrases such as “is protected by law”, “have passed laws”, and “thwart most lawsuits” to support their position and undermine the legitimacy of the demand for artefacts to be returned, as in extract (11).

(11) “In March, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said that the British Museum collection, including the Parthenon marbles, is protected by law.”(Text 4)

The act of fulfilling a prior commitment and expectation is addressed under the concept of fulfilment (Hood and Forey 2008). One subset of fulfilment is completion, which includes making demands for the return of artefacts. The writers use examples of completion in the present perfect tense, such as “has made such demands”, “has all asked”, and “has also requested”, in extracts (12) and (13).

(12) “It’s not the first time China has made such demands—which also echo the calls of other countries including Sudan, Nigeria, and Greece, which have all asked the British Museum to give back stolen artefacts.”(Text 5)

(13) “Egypt has long campaigned for the return of the Rosetta Stone, which was forcibly taken by the British Empire in 1801, and Greece has also requested the return of the Elgin marbles to the Parthenon.”(Text 7)

As shown in the examples above, graduation resources appear to grade up the historical significance of the objects, promote cultural pride, and present repatriation as a way of correcting historical injustices. These evaluative language choices can shape the attitudinal meanings of news and opinion pieces.

4.3. How Online Newspapers Reacted to the Vloggers’ Film

The third research question (RQ3) provides an analysis of the reports on the “Escape from the British Museum” short film on social media, which provides insights into the interaction between news coverage and social media netizens’ opinions. On 30 August 2023, a three-part web series entitled “Escape from the British Museum” was made available on Chinese social media platforms (Huo 2023). This was a short film that told the story of a Chinese relic, a jade teapot, personified by a vlogger as a helpless girl who escaped from the British Museum and returned to China to deliver family letters (Wei 2023). In the end, the teapot decided to return to the British Museum to await the day when China would receive all the artefacts in the British Museum through official channels (Hongyu 2023).

According to the data, different online news articles tended to take a selective approach to reporting social media reactions, focusing on comments that may have been more in line with their editorial stance. Texts 1 to 4 used more affective resources than texts 5 to 7, such as “we will come home in a glorious and dignified way” and “moved many to tears” in extracts (14) and (15), and graduation resources that broadened the scope such as “has gone viral”, “widespread”, and “nationwide” in extract (16). The use of evaluative and affective resources seems to raise awareness of the Chinese artefacts being displayed or stored in overseas museums.

(14) “Everyone says we are from a great country, and we Chinese don’t do things covertly. They believe someday we will come home in a glorious and dignified way.”(Text 3)

(15) “Details in the short video series, such as Chinese characters written with ink brush on English newspapers, and conversations between personified artefacts, moved many to tears.”(Text 3)

(16) “A three-episode Chinese internet drama, ‘Escape from the British Museum’, has gone viral on social media platforms in China, sparking widespread discussions online and striking an emotional chord nationwide.”(Text 3)

The combination of these affective and graduation resources could be interpreted as uniting the audience by allowing the community to express their feelings about the artefacts, such as the use of vivid imagery and appeals to authority. The personal anecdotes told by the jade teapot character in the film may have increased the emotional and attitudinal alignment for the return of artefacts. In contrast, texts 5–7 seemed to take a slightly different approach to reporting than texts 1–4. Quantifiers that refer to time and numbers (Hood and Forey 2008), such as “within a week”, “370 million views”, and “more than five million followers”, to report on the significant reactions to the short film, are often found in extracts (17) and (18).

(17) “First released on China’s version of TikTok, Douyin, the series has been played 270 million times on the platform. It has also seen its creators, who claim to be independent content makers, gaining more than five million followers on Chinese social media apps within one week.”(Text 5)

(18) “Since being published two weeks ago on Douyin—which, like TikTok, is owned by the Chinese developer ByteDance and hosts short-form, user-submitted videos—the series has racked up more than 370 m views.”(Text 6)

When texts 5–7 reported on the film, they offered some heteroglossic resources, referring to different sources of information (Martin and White 2005). For example, they sometimes referred to Chinese official media. The terms “state broadcaster CCTV” and “Chinese state media” were used in extracts (19–20). This may indicate that the film was in line with the ideas of the Chinese state media.

(19) “The series has also been strongly endorsed by state media. State broadcaster CCTV gave it a pat on the back this week, saying: ‘We are very pleased to see Chinese young people are passionate about history and tradition …’”(Text 5)

(20) “The plot of Escape from the British Museum, a series made by two social media influencers, echoes Chinese state media calls for the British government to make amends for ‘historical sins’ and return Chinese cultural relics.”(Text 6)

The metaphor of “gives it a pat on the back”, used by the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV to support the creation of the short film by young Chinese people, is shown in extract (21). These language choices can be interpreted as reflecting the editorial perspectives of different news organisations, and they appear to implicitly affect readers’ interpretations in terms of support or opposition to the issue.

Moreover, news organisations use relatively different approaches when reporting on netizens’ reactions and ideas about the “return of the artefacts”. Extracts (21) and (22) attempt to link the massive social media reaction to Chinese “rising nationalist sentiment” or “a nationalist line”:

(21) “Cultural heritage and ownership has become a more sensitive topic for the Chinese public in recent years amid rising nationalist sentiment.”(Text 5)

(22) “Although Chinese state media has tried to promote a nationalist line on the issue and accused the British Museum of harbouring ‘stolen cultural property’, Chinese social media users are divided.”(Text 6)

Texts 5 and 6 also quote several comments made by users of the social media sites Douyin and Weibo regarding the return of the artefacts. In extract (23), another Weibo user commented that the Cultural Revolution’s destruction of cultural relics was more serious than the British Museum’s storage of them. Extract (24) discusses the subsequent impact of the vloggers’ film, as seen in the current trend of dressing up as various ancient Chinese sculptures and paintings.

(23) “Another Weibo user replied: ‘There were more cultural artefacts destroyed during the Cultural Revolution than being stored by the British Museum, it is beyond your imagination.’”(Text 6)

(24) “The series has also inspired other influencers to dress up as characters from ancient Chinese paintings and sculptures.”.(Text 5)

Some texts, on the other hand, discuss the concept of homecoming in a slightly gloomy manner. Extracts (25) to (26), for example, refer to the video as “a solace” for “some Chinese” because the British Museum may be “unlikely” to return Chinese treasures “in real life”. In this way, the artefact is humanised, and the act of escape can be invoked to capture the attention of the Chinese public.

(25) “Maybe it is precisely because the British Museum is unlikely to return Chinese treasures in real life that the idea of these objects coming to life and escaping on their own has captured the imagination of the Chinese public.”(Text 4)

(26) “To some Chinese, the video series has been a solace.”(Text 4)

The examples above demonstrate different attitudes and graduation choices in appraisal systems used by different online news and opinion pieces. By examining the interpersonal meanings that these texts construct, we can better understand the linguistic landscape shaped by the shifting dynamics of media, cultural narratives, and international connections.

5. Conclusions

The British Museum collection appears to represent a complex historical record, with artefacts from the colonial period as well as more recent cultural exchanges (Glass 2004; Gosden and Knowles 2020; Hawkins 2023; Vrdoljak 2006). It is important to consider how meanings are conveyed to the public by examining the news discourse (King et al. 2021; Rhee et al. 2021). The present study offers a new approach to addressing how the use of grading resources in online news discourse can adjust and affect the intensity of language regarding the demand for the British Museum to return Chinese artefacts. By analysing the voices of the writers, we can better understand how these news texts convey attitudinal meanings and engagement with cultural heritage.

For research question 1 of this study, the high moral obligation to the return of the relics, addressed through the category of intensification, is projected by modal adjuncts such as “must”. Within the category of force, the quantifier “millions” is often used to express strong opinions on social media. The data also highlight the appeals to specificity and fulfilment, as evidenced by the use of “particularly” and the present perfect tense. Language conveys sociopolitical positions and attitudes, adds value, and expresses power (Obeng 2020). It also reinforces meanings rather than just conveying information. In relation to research question 2, specific patterns of frequency were found in relation to the four subcategories of intensification, quantification, specificity, and fulfilment. These patterns help us to understand how the most common graduation resources are used to convey meaning, such as emphasis, measure, and completion of a topic. Examining the frequency patterns and examples of these subcategories can contribute to our linguistic knowledge of writers’ attitudinal meanings and language strategies. When discussing heritage repatriation, the writers use various indicators pertaining to quantity and scope in time and space in order to convey the gravity and scope of the issue through their word choices. For example, a variety of quantification tokens are used, such as “some”, “many”, and “a number of”. Legal concepts and issues, such as “legal framework” and “lawsuit”, are frequently used as intensifiers in texts to give their arguments more force, legal authority, and national power. A relatively large number of tokens fall into the focus category, which is concerned with meeting the demand for the return of the relics. “Return back”, “request”, and “demand” are just a few of the tokens that are commonly found in the data. By unpacking the meanings embedded in the linguistic resources, we can develop a deeper understanding of the negotiations taking place between different nationalities in the quest for restitution. The third research question examined how different news outlets covered the same film. Some news articles tended to be more affective, using more affective resources, eliciting emotional responses from the audiences, and seeking more empathy and alignment from readers, while others seemed to use more quantifiers, referring to heteroglossic sources, and focusing on the latest vlogger/blogger trends. By examining the interpersonal meanings embedded in different news articles, a clearer and more comprehensive picture of cultural heritage repatriation in the news and media discourse can be projected.

This study adds to the growing body of research on language and social change by demonstrating the effectiveness of linguistic analysis in revealing interpersonal meanings and language strategies used in a sociocultural context (Dafouz-Milne 2008; Herring 2003; Malenkina and Ivanov 2018). We hope that the findings of the present study highlight the importance of interpersonal meanings as constructed in news texts, as well as the potential significance of language in framing public and global debates on the issue of cultural artefact repatriation.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abasi, Ali R., and Nahal Akbari. 2013. The discoursal construction of candidates in the tenth Iranian presidential elections: A positive discourse analytical case study. Journal of Language and Politics 12: 537–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abungu, George Okello. 2022. Victims or victors: Universal museums and the debate on return and restitution, Africa’s perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Museum Archaeology. Edited by Alice Stevenson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, Monica, and Helen Caple. 2010. Playing with environmental stories in the news—Good or bad practice? Discourse & Communication 4: 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafouz-Milne, Emma. 2008. The pragmatic role of textual and interpersonal metadiscourse markers in the construction and attainment of persuasion: A cross-linguistic study of newspaper discourse. Journal of Pragmatics 40: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthie, Emily. 2011. The British Museum: An imperial museum in a post-imperial world. Public History Review 18: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Derek. 2012. The Parthenon Sculptures and Cultural Justice. Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal 23: 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fine-Dare, Kathleen Sue. 2002. Grave Injustice: The American Indian Repatriation Movement and NAGPRA. Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, Peter. 2010. Attitudes to Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, Aaron. 2004. Return to sender: On the politics of cultural property and the proper address of art. Journal of Material Culture 9: 115–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, Hannah R. 2020. Legal complications of repatriation at the British Museum. Washington International Law Journal Association 30: 144. [Google Scholar]

- Gosden, Chris, and Chantal Knowles. 2020. Collecting Colonialism: Material Culture and Colonial Change. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- GT Staff Reporters. 2023. Voices Rise, Resonate Among Countries for Return of Relics from British Museum: Calling from Home. Global Times. August 29. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202308/1297223.shtml (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Halliday, M.A.K., and Christian M.I.M. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Sarah. 1996. Justifying repatriation of Native American cultural property. Indiana Law Journal 72: 723. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Amy. 2023. Viral Series about Chinese Teapot Escaping from British Museum to Become Film Series with 370 m Views Echoes Chinese State Media Calls for Return of Cultural Relics. The Guardian. September 20. Available online: https://amp.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/20/viral-douyin-series-chinese-teapot-escaping-british-museum-film (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Herring, Susan C. 2003. Media and language change: Introduction. Journal of Historical Pragmatics 4: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongyu, Liang Jun. 2023. Internet Drama about Lost Artifacts Touches Chinese Netizens. People’s Daily Online. September 11. Available online: http://en.people.cn/n3/2023/0911/c90000-20070334.html (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Hood, Susan, and Gail Forey. 2008. The interpersonal dynamics of call-centre interactions: Co-constructing the rise and fall of emotion. Discourse and Communication 2: 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, Susan. 2006. The persuasive power of prosodies: Radiating values in academic writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 5: 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Zhengxin. 2023. Return Looted Relics to Countries of Origin. China Daily. September 12. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202309/12/WS64ff949fa310d2dce4bb5290.html (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Jin, Jinxiu. 2019. Political News Discourse Analysis Based on an Attitudinal Perspective of the Appraisal Theory-Taking the New York Times’ Report China-DPRK Relations as an Example. Theory and Practice in Language Studies 9: 1357–61. [Google Scholar]

- King, Ellie, M. Paul Smith, Paul F. Wilson, and Mark A. Williams. 2021. Digital Responses of UK Museum Exhibitions to the COVID-19 Crisis, March–June 2020. Curator: The Museum Journal 64: 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malenkina, Nadezhda, and Stanislav Ivanov. 2018. A linguistic analysis of the official tourism websites of the seventeen Spanish Autonomous Communities. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 9: 204–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, James R., and Peter Robert White. 2005. The Language of Evaluation: Appraisal in English. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, James Robert, and David Rose. 2007. Working with Discourse: Meaning Beyond the Clause, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Merryman, John Henry. 1985. Thinking about the Elgin marbles. Michigan Law Review 83: 1881–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, Samuel Gyasi. 2020. Grammatical pragmatics: Language, power and liberty in Ghanaian political discourse. Discourse & Society 31: 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, Bo-A, Federico Pianzola, and Gang-Ta Choi. 2021. Analyzing the museum experience through the lens of Instagram posts. Curator: The Museum Journal 64: 529–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabao, Collen. 2016. Arguments for an appraisal linguistic discourse approach to the analysis of “objectivity” in “hard” news reports. African Journalism Studies 37: 40–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, Carmen. 2023. Hit Chinese Video Series Stokes Calls for British Museum to Return Artefacts. The Straits Times. September 7. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/hit-chinese-tiktok-series-stokes-calls-for-british-museum-to-return-artefacts (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Vrdoljak, Ana Filipa. 2006. International Law, Museums and the Return of Cultural Objects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Yau Ni. 2023a. “But it’s truly aggravating and depressing”: Voicing counter-expectancy in US–Philippines service interactions. Journal of Intercultural Communication 23: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Yau Ni Jenny. 2017. Construing negotiation: The role of voice quality features in American-Filipino business telephone conversations. Language and Dialogue 7: 137–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Yau Ni Jenny. 2023b. Structuring logical relations in workplace English telephone negotiation. International Journal of Language Studies 17: 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Fan, and Derek Cai. 2023. British Museum: Chinese TikTok Hit Amplifies Calls for Return of Artefacts. BBC News. September 6. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-66714549.amp (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Wei, Wei. 2023. If the British Museum Isn’t Taking Good Care of Relics, Chinese want Theirs Back. South China Morning Post. September 10. Available online: https://amp.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3233626/if-british-museum-isnt-taking-good-care-relics-chinese-want-theirs-back (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- White, Peter Robert. 2003. Beyond modality and hedging: A dialogic view of the language of intersubjective stance. Text & Talk 23: 259–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Peter Robert. 2008. Interpersonal Semantics: Applying Appraisal—Analyzing Attitude, Alignment and Authorial Voice in Student Writing and Mass Communicative Discourse. Paper presented at the Pre-ISFC2008 Winter Institute at the Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, July 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- White, Peter Robert. 2009. Media power and the rhetorical potential of the “hard news” report–attitudinal mechanisms in journalistic discourse. Käännösteoria, Ammattikielet ja Monikielisyys. VAKKI: N Julkaisut 36: 30–49. [Google Scholar]

- White, Peter Robert. 2012. Exploring the axiological workings of ‘reporter voice’news stories—Attribution and attitudinal positioning. Discourse, Context & Media 1: 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Hui. 2017. China, Cultural Heritage, and International Law. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).