Emotional Profiles of Facebook Pages: Audience Response to Political News in Hong Kong

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Audience Engagement on Social Media

2.1. Audience’s Like, Emotional Reaction, and Share

2.2. Cultural Differences in Emotional Engagement with News on Facebook

3. Public Emotions around Politics in Networked Social Media

4. Theoretical Framework

5. Political Landscape of News in Hong Kong

6. Data and Methods

6.1. Media Sampling

6.2. Media Categorization

6.3. Time Sampling, Data Collection, and Pre-Processing of Posts

6.4. Topic Modeling of Posts

6.5. Emotional Analysis of Audience

6.6. Emotional Profiling of Facebook Pages

6.7. Research Hypotheses

6.8. Analyses

- The volume of all the posts published by each of the news pages and media categories;

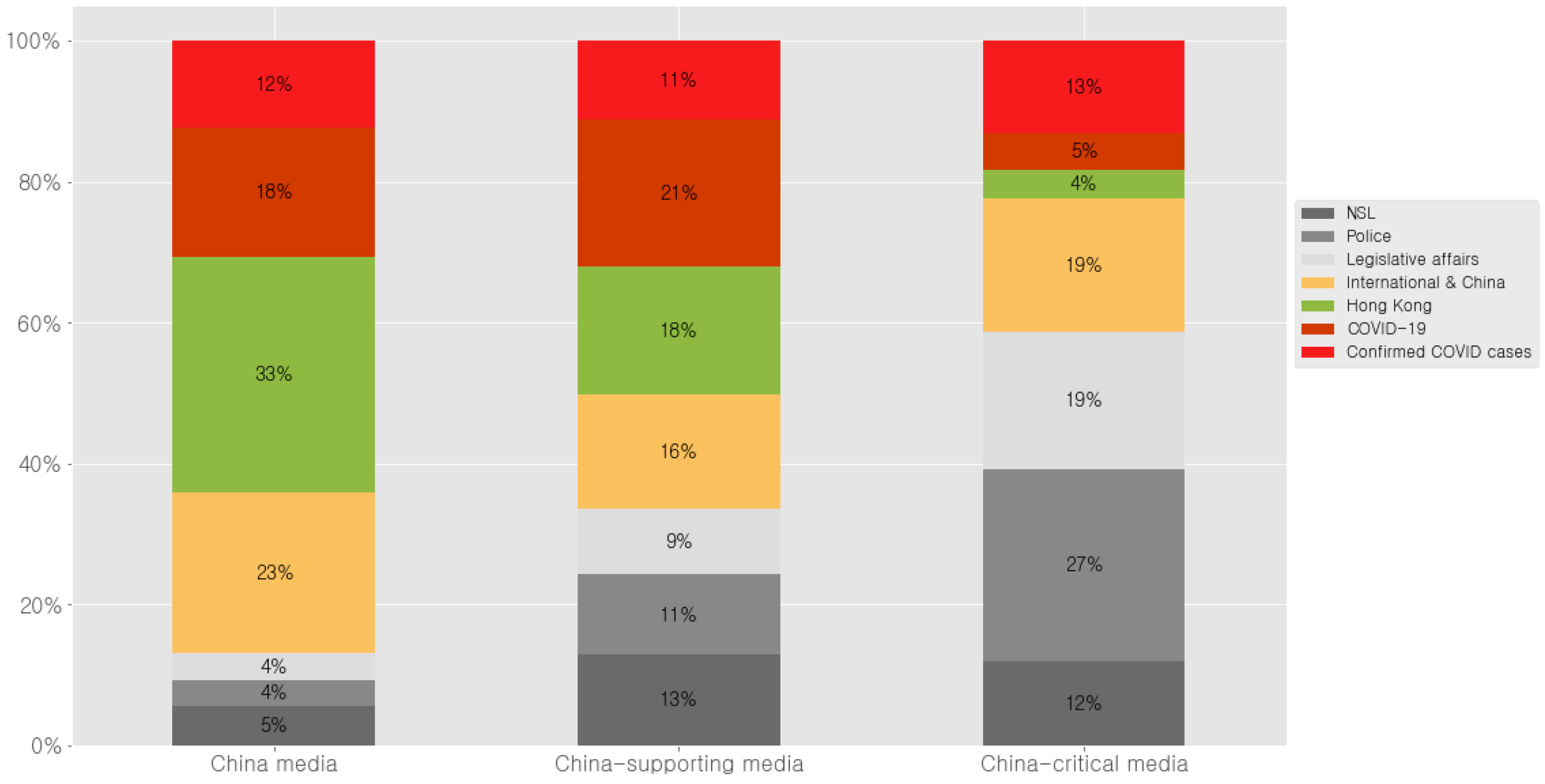

- The news agenda, measured by the proportion of the news topics above the set threshold in all the posts, of each of the news pages and media categories.

- The level and proportion of each of the emotional reactions made by readers to the political posts of each of the media categories and news pages;

- The correlations between the level of each of the emotional reactions and the number of news shares as well as the number of comments among the political posts of the media categories.

7. Results

7.1. Volume of News Publishing

7.2. News Agenda

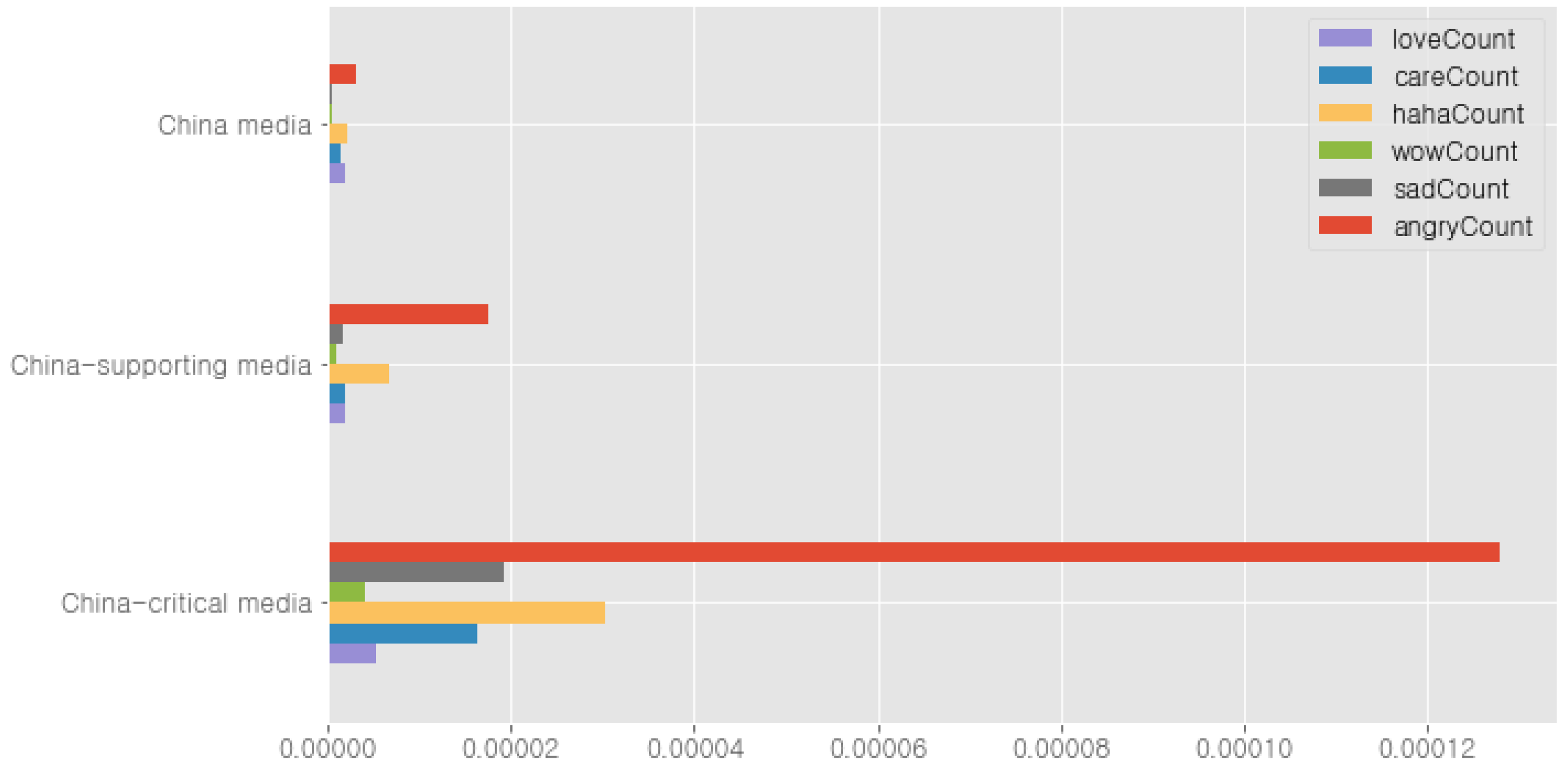

7.3. Emotional Intensity

7.4. Structure of Emotion

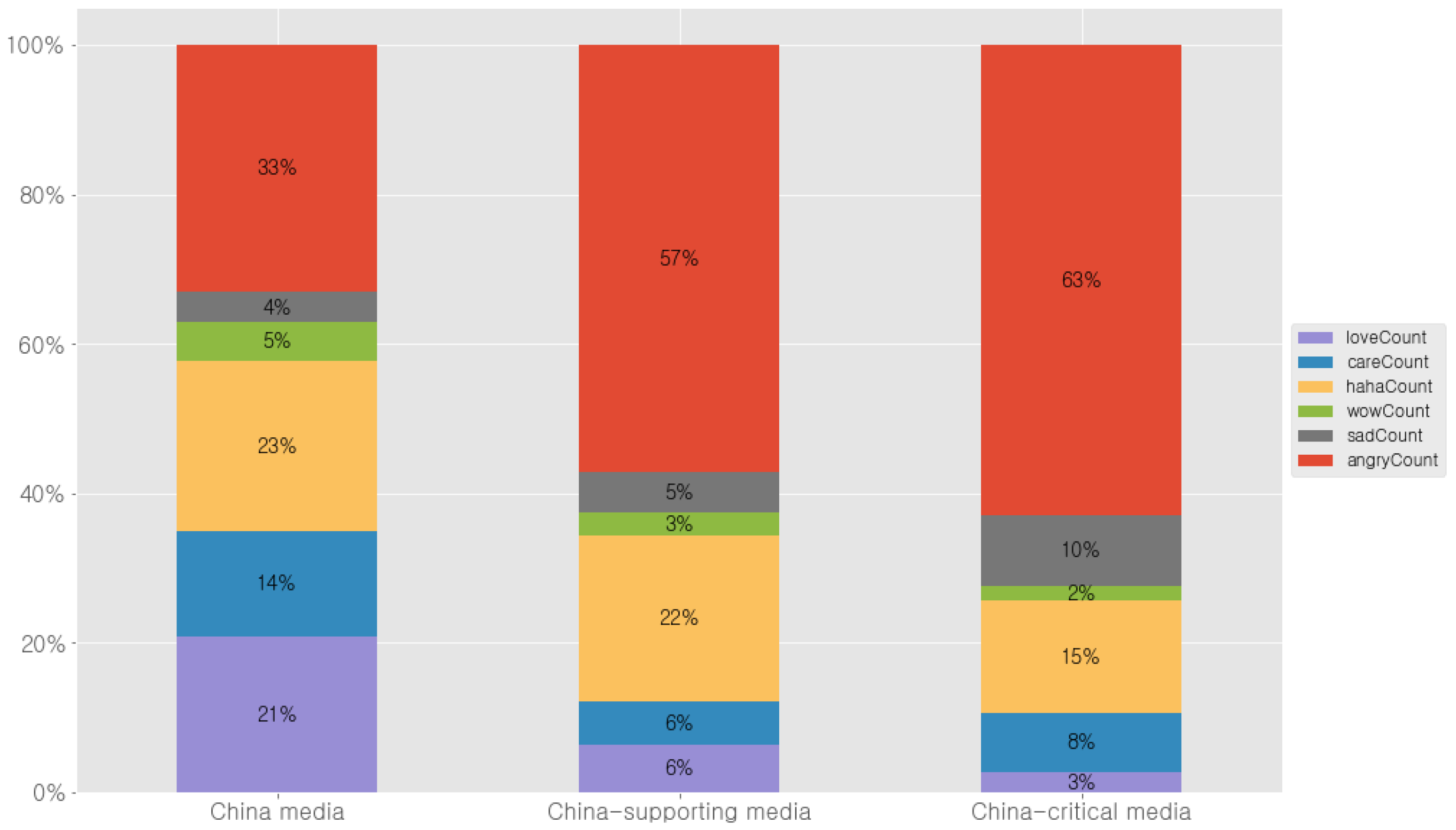

7.4.1. Proportion of Different Emotional Reactions

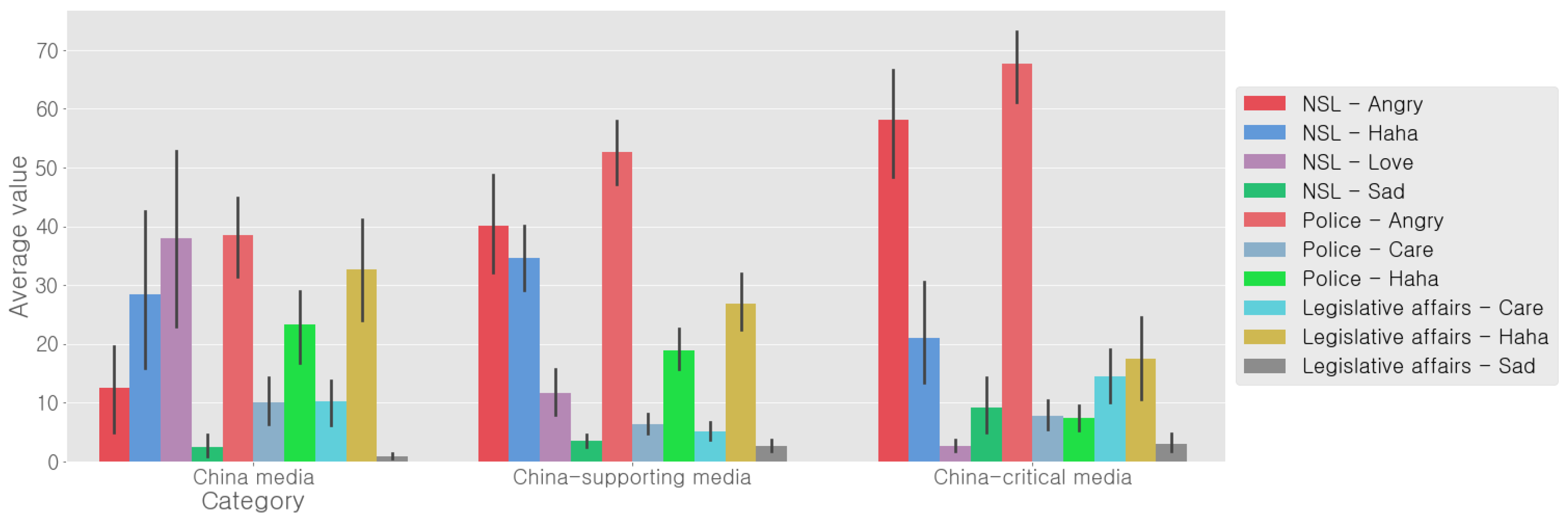

7.4.2. Emotional Profiles

7.5. Angry Reaction and News Share

8. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Ta Kung Pao, Wen Wei Po, and Hong Kong Commercial Daily are widely recognized as Chinese-language official newspapers of the Chinese Party-state in Hong Kong (called local Party papers here). The three papers have been indirectly owned by the Chinese government’s Liaison Office in Hong Kong (CLO). Lion Rock Daily is a free newspaper co-owned by Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po; Dot Dot News is owned by the top personnel of Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po. Orange News is indirectly owned by CLO. |

| 2 | For an explanation of China’s United Front work, see https://thediplomat.com/2018/02/chinas-united-front-work-propaganda-as-policy/ (accessed on 5 May 2023) |

| 3 | From the “list of registered newspapers”, the “list of analogue sound broadcasting services in Hong Kong” and the “list of licensed broadcasting services in Hong Kong”, we excluded English-language newspapers, business media, and other specialist media, and non-domestic television service operators. We identified four China-supporting news providers outside the government lists. Hk01.com is the largest digital native news provider in Hong Kong, and is generally considered pro-China. Hk01.com ran two separate Facebook pages on society and politics, both of which we included in our comparison. |

| 4 | Differences between China media and China-critical media for the haha reaction and between China media and China-supporting media for the care reaction are not significant. |

| 5 | Differences between China media and China-supporting media for the wow reaction is significant at the 0.01 level, and between China media and China-critical media for the care reaction is not significant. |

References

- Alswaidan, Nourah, and Mohamed El Bachir Menai. 2020. A survey of state-of-the-art approaches for emotion recognition in text. Knowledge and Information Systems 62: 2937–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, Charlie. 2015. How Journalism Is Turning Emotional and What That Might Mean for News. POLIS Blog. Available online: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63822/ (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Centre for Communication and Public Opinion Survey (CCPOS). 2020. Research Report on Public Opinion during the Anti-Extradition Bill (Fugitive Offenders Bill) Movement in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Chung-Hong, and King-Wa Fu. 2017. The relationship between cyberbalkanization and opinion polarization: Time-series analysis on Facebook pages and opinion polls during the Hong Kong Occupy Movement and the associated debate on political reform. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 22: 266–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Joseph Man, and Chin-Chuan Lee. 1989. Shifting journalistic paradigms: Editorial stance and political transition in Hong Kong. The China Quarterly 117: 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Joseph Man, and Chin-Chuan Lee. 1991. Power change, co-optation, accommodation: Xinhua and the press in transitional Hong Kong. The China Quarterly 126: 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Michael, Francis Lee, and Hsuan-Ting Chen. 2020. Hong Kong. In Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020. Edited by Nic Newman, Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. Available online: https://www.digitalnewsreport.org/survey/2020/hong-kong-2020/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Cheng, Edmund W., Francis L. F. Lee, Samson Yuen, and Gary Tang. 2022. Total mobilization from below: Hong Kong’s freedom summer. The China Quarterly 251: 629–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Lilian. 2022. Hong Kong’s graft-buster charges 4 for allegedly urging others to cast blank ballots by sharing posts from fugitive activists in 2021 Legco election. South China Morning Post. November 9. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/law-and-crime/article/3199014/hong-kongs-graft-buster-charges-4-allegedly-urging-others-cast-blank-ballots-sharing-posts-fugitive (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Corner, John. 2017. Afterword: Reflections on media engagement. Media Industries 4: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creery, Jennifer. 2020. Hongkongers purge social media, delete accounts as Beijing passes national security law. Hong Kong Free Press. July 3. Available online: https://hongkongfp.com/2020/07/03/hongkongers-purge-social-media-delete-accounts-as-beijing-passes-national-security-law/ (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Eberl, Jakob-Moritz, Petro Tolochko, Pablo Jost, Tobias Heidenreich, and Hajo G. Boomgaarden. 2020. What’s in a post? How sentiment and issue salience affect users’ emotional reactions on Facebook. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 17: 48–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Conill, Raul, Michael Karlsson, Mario Haim, Aske Kammer, Dag Elgesem, and Helle Sjøvaag. 2021. Toward ‘Cultures of Engagement’? An exploratory comparison of engagement patterns on Facebook news posts. New Media & Society 25: 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Filmer, Paul. 2003. Structures of feeling and socio-cultural formations: The significance of literature and experience to Raymond Williams’s sociology of culture. The British Journal of Sociology 54: 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, Nicholas, Valerie Belair-Gagnon, and Colin Agur. 2018. Media capture with Chinese characteristics: Changing patterns in Hong Kong’s news media system. Journalism 19: 1165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, Bharath. 2020. Weaponizing white thymos: Flows of rage in the online audiences of the alt-right. Cultural Studies 34: 892–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganster, Tina, Sabrina C. Eimler, and Nicole C. Krämer. 2012. Same same but different!? The differential influence of smilies and emoticons on person perception. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 15: 226–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerlitz, Carolin, and Anne Helmond. 2013. The like economy: Social buttons and the data-intensive web. New Media & Society 15: 1348–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Logan Molyneux, and Pei Zheng. 2014. Social media, political expression, and political participation: Panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. Journal of Communication 64: 612–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Steven L. 1989. The socialization of children’s emotions: Emotional culture, competence, and exposure. In Children’s Understanding of Emotion. Edited by Carolyn Saarni and Paul L. Harris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 319–49. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Sage L. 2019. A wink and a nod: The role of emojis in forming digital communities. Multilingua 38: 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Derek, and James P. Cross. 2017. Exploring the political agenda of the european parliament using a dynamic topic modeling approach. Political Analysis 25: 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haim, Mario, Anna Sophie Kümpel, and Hans-Bernd Brosius. 2018. Popularity cues in online media: A review of conceptualizations, operationalizations, and general effects. Studies in Communication and Media 7: 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiaeshutter-Rice, Dan, and Brian Weeks. 2021. Understanding Audience Engagement with Mainstream and Alternative News Posts on Facebook. Digital Journalism 9: 519–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1979. Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. American Journal of Sociology 85: 551–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, Jeff, Keach Hagey, and Emily Glazer. 2023. Facebook wanted out of politics. It was messier than anyone expected. The Wall Street Journal. January 5. Available online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-politics-controls-zuckerberg-meta-11672929976?mod=djemalertNEWS (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Jasper, James M. 1998. The emotions of protest: Affective and reactive emotions in and around social movements. Sociological Forum 13: 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, Pablo, Marcus Maurer, and Joerg Hassler. 2020. Populism fuels love and anger: The impact of message features on users’ reactions on Facebook. International Journal of Communication 14: 2081–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Cheonsoo, and Sung-Un Yang. 2017. Like, comment, and share on Facebook: How each behavior differs from the other. Public Relations Review 43: 441–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2018. Diversifying likes: Relating reactions to commenting and sharing on newspaper Facebook pages. Journalism Practice 12: 326–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Anders Olof. 2019. News use as amplification: Norwegian national, regional, and hyperpartisan media on Facebook. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96: 721–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lünich, Marco, Patrick Rössler, and Lena Hautzer. 2012. Social navigation on the internet: A framework for the analysis of communication processes. Journal of Technology in Human Services 30: 232–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meraz, Sharon, and Zizi Papacharissi. 2013. Networked gatekeeping and networked framing on# Egypt. The International Journal of Press/Politics 18: 138–66. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, Dumisani, Admire Mare, and Trust Matsilele. 2019. Analytics-driven journalism? Editorial metrics and the reconfiguration of online news production practices in African newsrooms. Digital Journalism 7: 490–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, Philip M. 2012. Audience evolution and the future of audience research. International Journal on Media Management 14: 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nip, Joyce Y. M., King-Wah Fu, and Yu-Chung Cheng. 2020. Communication Battles on Facebook in Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement and Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3702674 (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Papacharissi, Zizi. 2014. Affective Publics: Sentiment, Technology, and Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Picone, Ike, Jelena Kleut, Tereza Pavlíčková, Bojana Romic, Jannie Møller Hartley, and Sander De Ridder. 2019. Small acts of engagement: Reconnecting productive audience practices with everyday agency. New Media & Society 21: 2010–28. [Google Scholar]

- Quandt, Thorsten. 2018. Dark participation. Media and Communication 6: 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radway, Janice A. 1991. Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, Klaus R. 2005. What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information 44: 695–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehl, Annika, Alessio Cornia, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. Public Service News and Social Media. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Fei, Wenting Yu, Chen Min, Qianying Ye, Chuanli Xia, Tianjiao Wang, and Yi Wu. 2021. Cybercan: A New Dictionary for Cantonese Social Media Text Segmentation. SocArXiv Papers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouse, Eric. 2005. Feeling, emotion, affect. M/c Journal 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S., J. Wang, R. Zhang, Q. Su, and J. Xiao. 2022. Federated Non-negative Matrix Factorization for Short Texts Topic Modeling with Mutual Information. Paper Presented at 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Padua, Italy, July 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 2020. 互联网信息服务管理办法 (Administrative Measures for Internet Information Services). Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2011/content_1860864.htm (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Stockmann, Daniela. 2013. Media Commercialization and Authoritarian Rule in China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm Wilkerson, Heloisa, Martin J. Riedl, and Kelsey N. Whipple. 2021. Affective affordances: Exploring Facebook reactions as emotional responses to hyperpartisan political news. Digital Journalism 9: 1040–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A. 2020. Jieba. Available online: https://github.com/fxsjy/jieba (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Thoits, Peggy A. 1989. The sociology of emotions. Annual Review of Sociology 15: 317–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Ye, Thiago Galery, Giulio Dulcinati, Emilia Molimpakis, and Chao Sun. 2017. Facebook sentiment: Reactions and emojis. Paper Presented at Fifth International Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Social Media, Valencia, Spain, April 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2020. An emotional turn in journalism studies? Digital Journalism 8: 175–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Subcategory | Media Name | Follower No. * |

|---|---|---|---|

| China media (n = 12) | China national Party media | cctvhongkong | 18.5K |

| ChinaNewsService | 1.16M | ||

| Rmwhk | 1.53M | ||

| TongMediaHK | 430.0K | ||

| XinhuaHK | 467.5K | ||

| China local Party media | dotdotnews | 21.5K | |

| hkorangenews | 254.1K | ||

| lionrockdailyhk | 6.5K | ||

| TWKK.HK | 20.9K | ||

| wenweipo | 7.4K | ||

| China national/global market media | Hongkongsina | 158.6K | |

| PhoenixTVHK | 28.4K | ||

| China-supporting media (n = 28) | HK pro-China digital media | Bastillepost | 1.03M |

| flamingwheels2019 | 75 | ||

| hk01.news | 456.2K | ||

| hk01wemedia | 672.3K | ||

| hkgpaocomhk | 63.2K | ||

| HongKongGoodNews | 615.1K | ||

| HKInsights | 50.6K | ||

| kinliuhk | 33.7K | ||

| litenewshk | 22.2K | ||

| looop.hk | 34.2K | ||

| masterinsightcom | 67.4K | ||

| silentmajorityhk | 345.2K | ||

| speakouthk | 520.7K | ||

| tap2world | 511.8K | ||

| thinkhongkong | 222.4K | ||

| todayreview88 | 170.4K | ||

| HK mainstream media | am730hk | 457.3K | |

| crhknews | 44.3K | ||

| ctnnet | 783 | ||

| headlinehk | 202.9K | ||

| icable.news | 924.6K | ||

| MetroDailyNews | 9.5K | ||

| mingpaoinews | 430.5K | ||

| now.comNews | 571.6K | ||

| onccnews | 750.2K | ||

| RTHKVNEWS | 999.6K | ||

| singtaohk | 49.0K | ||

| Skyposthk | 811.4K | ||

| China-critical media (n = 12) | HK centrist digital media | fans.hkgolden | 527.4K |

| HK.CitizenMedia | 58.1K | ||

| theinitium | 335.0K | ||

| therightnewshk | 8.5K | ||

| truthmediahk | 57.9K | ||

| HK independent digital media | hkcnews | 229.9K | |

| inmediahknet | 682.8K | ||

| maddogdailyhk | 103.1K | ||

| post852 | 75K | ||

| Standnewshk | 1.65M | ||

| HK anti-China traditional media | hk.nextmedia | 2.835M | |

| nextmagazinefansclub | 54.1K |

| Topic No. | Topic Label | Top 10 Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | NSL | NSL, Hong Kong region, Hong Kong version, legislate, country, Basic Law, central authorities, national security, National People’s Congress, bill |

| 1 | COVID-19 | New corona, pneumonia, epidemic, virus, mouth mask, health, new strain, epidemic prevention, test, fight the epidemic |

| 2 | International & China | United States, China, Trump, president, sanction, Sino-US, Pompeo, Britain, relations, protests |

| 3 | Police | Police, police officer, citizen, defendant, arrest, Causeway Bay, man, arrested, rally, scene |

| 4 | Hong Kong | Hong Kong, country, security, safeguard, legislate, one country–two systems, central authorities, law, national security, society |

| 5 | Confirmed COVID cases | Confirmed diagnosis, case, newly added, Hong Kong, centre, infection, sick case, accumulated, preliminary, new strain |

| 6 | Legislative affairs | Legislative Council, election, primary election, democratic camp, vote, meeting, enter into the election, councillor, government, mutual destruction |

| Topic | Emotion | China Media | China-Supporting Media | China-Critical Media |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSL | Love | 31.6% †§ | 7.9% *§ | 2.5% *† |

| Care | 19.7% †§ | 4.8% * | 6.1% * | |

| Haha | 28.0% †§ | 29.9% *§ | 25.2% *† | |

| Wow | 1.8% †§ | 2.4% *§ | 2.1% *† | |

| Sad | 1.0% †§ | 3.5% *§ | 7.9% *† | |

| Angry | 17.8% †§ | 51.6% *§ | 56.3% *† | |

| Police | Love | 7.4% †§ | 5.2 *§ | 2.4% *† |

| Care | 9.9% | 7.4% § | 7.3% † | |

| Haha | 20.0% § | 13.3% § | 8.5% *† | |

| Wow | 9.3% †§ | 4.1% *§ | 1.8% *† | |

| Sad | 8.2% § | 9.1% § | 11.5% *† | |

| Angry | 45.1% †§ | 60.9% *§ | 68.4% *† | |

| Legislative affairs | Love | 27.2% †§ | 5.3% *§ | 3.1% *† |

| Care | 11.7% †§ | 5.4% *§ | 11.8% *† | |

| Haha | 20.6% †§ | 25.1% *§ | 21.9% *† | |

| Wow | 3.0% †§ | 1.9% * | 2.4% * | |

| Sad | 1.5% †§ | 1.9% *§ | 4.2% *† | |

| Angry | 36.0% †§ | 60.4% *§ | 56.7% *† |

| China Media | China-Supporting Media | China Critical Media | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average share count per political post | 14.9 | 63.3 | 251.9 |

| Average comment count per political post | 26.2 | 150.2 | 250.3 |

| China Media | China-Supporting Media | China-Critical Media | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Reaction | Share | Comment | Share | Comment | Share | Comment |

| love | 0.8489 *** | 0.7583 ** | 0.6826 **** | 0.8608 **** | 0.8404 *** | 0.9030 **** |

| care | 0.8013 ** | 0.6996 * | 0.7585 **** | 0.8694 **** | 0.7674 ** | 0.78418 ** |

| haha | 0.6552 * | 0.8418 * | 0.4885 ** | 0.7849 **** | 0.4197 | 0.2671 |

| wow | 0.3743 | 0.2279 | −0.0586 | −0.0849 | 0.9473 **** | 0.8184 ** |

| sad | 0.3460 | 0.2647 | 0.5776 ** | 0.5360 ** | 0.9166 **** | 0.7653 ** |

| angry | 0.3900 | 0.3814 | 0.6628 *** | 0.6472 *** | 0.8724 *** | 0.7804 ** |

| All reactions | 0.7828 ** | 0.7411 ** | 0.7091 **** | 0.8160 **** | 0.8869 *** | 0.7941 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nip, J.Y.M.; Berthelier, B. Emotional Profiles of Facebook Pages: Audience Response to Political News in Hong Kong. Journal. Media 2023, 4, 1021-1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040065

Nip JYM, Berthelier B. Emotional Profiles of Facebook Pages: Audience Response to Political News in Hong Kong. Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(4):1021-1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040065

Chicago/Turabian StyleNip, Joyce Y. M., and Benoit Berthelier. 2023. "Emotional Profiles of Facebook Pages: Audience Response to Political News in Hong Kong" Journalism and Media 4, no. 4: 1021-1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040065

APA StyleNip, J. Y. M., & Berthelier, B. (2023). Emotional Profiles of Facebook Pages: Audience Response to Political News in Hong Kong. Journalism and Media, 4(4), 1021-1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4040065