Motivations, Knowledge, Efficacy, and Participation: An O-S-O-R Model of Second Screening’s Political Effects in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Digital Media and Political Participation

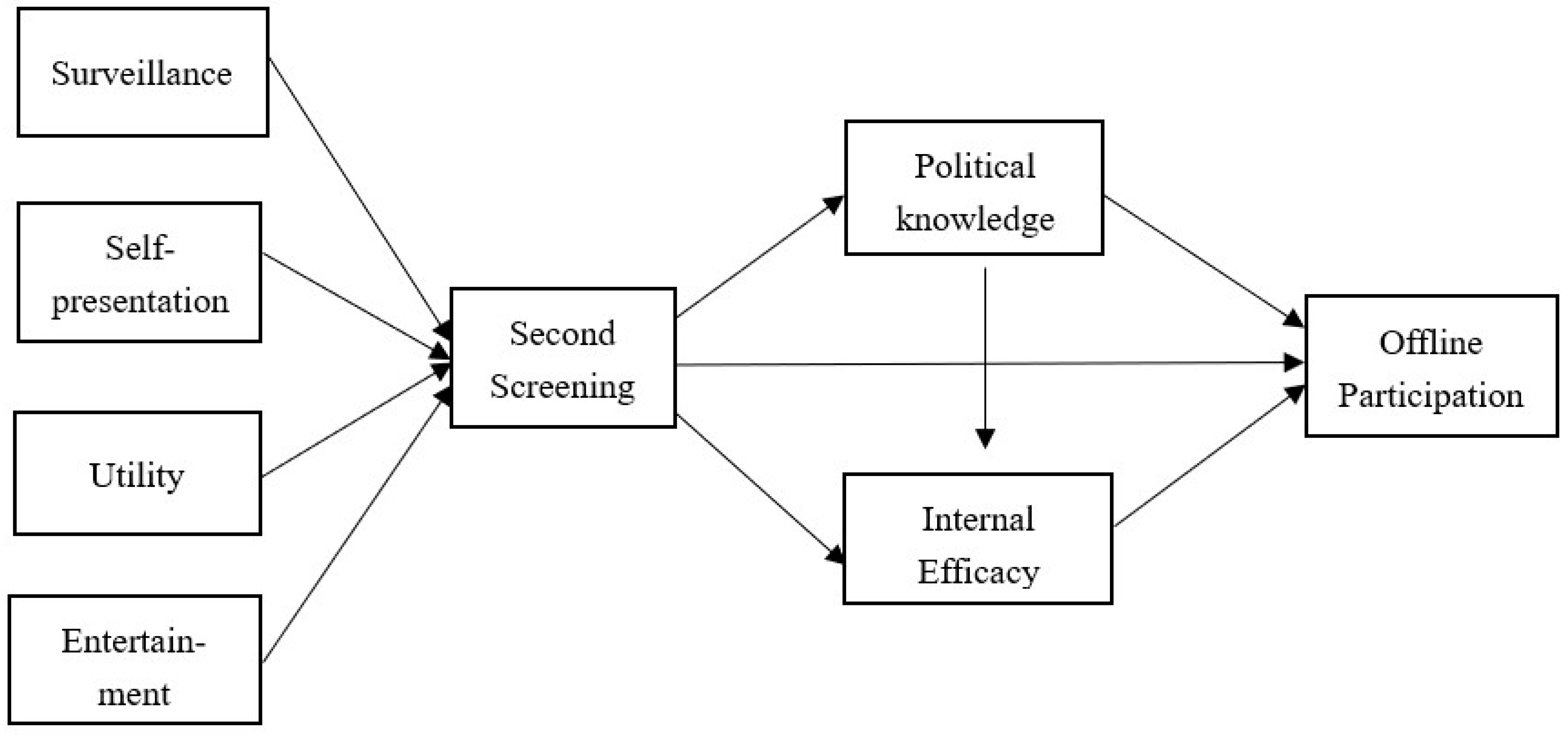

4. The O-S-O-R Model

5. Motivations of Second Screening

6. Second Screening’s Relationships with Political Knowledge, Internal Political Efficacy, and Political Participation

7. Political Knowledge, Internal Political Efficacy, and Political Participation

8. Method

8.1. Sampling

8.2. Measures

9. Results

10. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- “The two conferences” refers to the National People’s Congress and what conference?

- In China, the only organization possessing the legislation right is?

- What is Hu Chunhua’s current position?

- Who is the current chairman of Chinese People’s Political Consultation?

- An agency was established in March 2018 to enhance the party’s leadership in anti-corruption work. This organization incorporates the functions of local supervision departments and inspection agencies. What is the name of this agency?

- Proposed in the 2018 Chinese Government Annual Report, mobile phone service fees will be reduced by how many percent?

- Proposed by Li Keqiang, Premier of the State Council, the individual income tax will be applied to individuals with a minimum monthly income of how many yuan?

- Chairman Xi Jinping gave a speech at the closing ceremony of the 13th National People’s Congress. In this speech, a word had been mentioned 84 times. The media claims this word represents the core of the party’s leadership. What is the word?

- People with what identity are not eligible to be an official of Chinese People’s Political Consultation?

- What is the main function of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference?

References

- AdColony. 2021. Second Screening: Understanding Usage and Audiences. AdColony. Available online: https://www.adcolony.com/blog/2021/02/02/second-screening-understanding-usage-and-audiences/ (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2001. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology 52: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnidge, Matthew, Trevor Diehl, and Hernando Rojas. 2019. Second screening for news and digital divides. Social Science Computer Review 37: 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, Leticia. 2015. Political news in the news feed: Learning politics from social media. Mass Communication and Society 19: 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, Shelley. 2020. Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Communication Research 47: 947–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Angus, Gerald Gurin, and Warren Edward Miller. 1954. The Voter Decides. Evanston: Row, Peterson. [Google Scholar]

- Cerf, Vinton G. 2016. Information and misinformation on the internet. Communications of the ACM 60: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2017. The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Michael, Hsuan-Ting Chen, and Francis Lee. 2017. Examining the roles of mobile and social media in political participation: A cross-national analysis of three Asian societies using a communication mediation approach. New Media & Society 19: 2003–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Hsuan-Ting. 2021. Second screening and the engaged public: The role of second screening for news and political expression in an OSROR model. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 98: 526–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wenhong. 2014. Taking stock, moving forward: The Internet, social networks and civic engagement in Chinese societies. Information, Communication & Society 17: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhuo, and Michael Chan. 2017. Motivations for social media use and impact on political participation in China: A cognitive and communication mediation approach. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 20: 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Daily. 2019. WeChat Reports Expanding Usage as Spring Festival Holiday Goes Digital. chinadaily.com.cn. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201902/10/WS5c6044d9a3106c65c34e88b2.html (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Cho, Jaeho, Dhavan V. Shah, Jack M. McLeod, Douglas M. McLeod, Rosanne M. Scholl, and Melissa R. Gotlieb. 2009. Campaigns, reflection, and deliberation: Advancing an O-S-R-O-R model of communication effects. Communication Theory 19: 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Boreum, and Yoonhyuk Jung. 2016. The Effects of Second-Screen Viewing and the Goal Congruency of Supplementary Content on User Perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior 64: 347–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, Peter. 2009. Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication, and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Wayne, and Chad Cross. 2013. Biostatistics: A Foundation for Analysis in the Health Sciences, 10th ed. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Patrícia, and Javier Serrano-Puche. 2020. Multi-Needs for Multi-Screening: Practices, Motivations, and Attention Distribution. Palabra Clave 23: e2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveland, William P. Jr. 2001. The cognitive mediation model of learning from the news: Evidence from non-election, off-year election, and presidential election contexts. Communication Research 28: 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eveland, William P., Jr. 2002. News information processing as mediator of the relationship between motivations and political knowledge. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 79: 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Giglietto, Fabio, and Donatella Selva. 2014. Second screen and participation: A content analysis on a full season dataset of tweets. Journal of Communication 64: 260–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Alberto Ardèvol-Abreu, and Andreu Casero-Ripollés. 2021. WhatsApp political discussion, conventional participation and activism: Exploring direct, indirect and generational effects. Information, Communication & Society 24: 201–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, and James H. Liu. 2017. Second screening politics in the social media sphere: Advancing research on dual screen use in political communication with evidence from 20 countries. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 61: 193–219. [Google Scholar]

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Logan Molyneux, and Pei Zheng. 2014. Social media, political expression, and political participation: Panel analysis of lagged and concurrent relationships. Journal of Communication 64: 612–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil de Zúñiga, Homero, Victor Garcia-Perdomo, and Shannon C. McGregor. 2015. What is second screening? Exploring motivations of second screen use and its effect on online political participation. Journal of Communication 65: 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocevar, Kristin Page, Andrew J. Flanagin, and Miriam J. Metzger. 2014. Social media self-efficacy and information evaluation online. Computers in Human Behavior 39: 254–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Philip N. 2010. The Digital Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Information Technology and Political Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Philip N., and Muzammil Hussain. 2013. Democracy’s Fourth Wave? Digital Media and the Arab Spring. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Li-tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, Ki Deuk, and Jinhee Kim. 2015. Differential and interactive influences on political participation by different types of news activities and political conversation through social media. Computers in Human Behavior 45: 328–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Nakwon, Yonghwan Kim, and Homero Gil de Zúñiga. 2011. The mediating role of knowledge and efficacy in the effects of communication on political participation. Mass Communication and Society 14: 407–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, Barbara K., and Thomas J. Johnson. 2002. Online and in the know: Uses and gratifications of the web for political information. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 46: 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kenski, Kate, and Natalie Jomini Stroud. 2006. Connections between Internet use and political efficacy, knowledge, and participation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 50: 173–92. [Google Scholar]

- King, Gary, Jennifer Pan, and Margaret E. Roberts. 2013. How censorship in China allows government criticism but silences collective expression. American Political Science Review 107: 326–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., Helmut Norpoth, William G. Jacoby, and Herbert F. Weisberg. 2008. The American Voter Revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Yiben, Bumsoo Kim, and Yonghwan Kim. 2021. Towards Engaged Citizens: Influences of Second Screening on College Students’ Political Knowledge and Participation. Southern Communication Journal 86: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macafee, Timothy. 2013. Some of these things are not like the others: Examining motivations and political predispositions among political Facebook activity. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 2766–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel, and Robert B. Zajonc. 1985. The cognitive perspective in social psychology. In Handbook of Social Psychology. Edited by Gardner Lindzey and Elliot Aronson. New York: Random House, vol. 1, pp. 137–230. [Google Scholar]

- McGregor, Shannon C., Rachel R. Mourão, Ivo Neto, Joseph D. Straubhaar, and Alan Angeluci. 2017. Second screening as convergence in Brazil and the United States. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 61: 163–81. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Jack M., Dietram A. Scheufele, and Patricia Moy. 1999. Community, communication, and participation: The role of mass media and interpersonal discussion in local political participation. Political Communication 16: 315–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, Jack M., Gerald M. Kosicki, and Douglas M. McLeod. 1994. The expanding boundaries of political communication effects. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Edited by Jennings Bryant and Dolf Zillmann. Hilsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 123–62. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Jack M., Jessica Zubric, Heejo Keum, Sameer Deshpande, Jaeho Cho, Susan Stein, and Mark Heather. 2001. Reflecting and Connecting: Testing a Communication Mediation Model of Civic Participation. Paper presented at 84th Annual Convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Washington, DC, USA, August 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammed, Sadiq, and Saji K. Mathew. 2022. The disaster of misinformation: A review of research in social media. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 13: 271–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2018. China Statistical Yeatbook; National Bureau of Statistics. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2018/indexch.htm (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Niemi, Richard G., Stephen C. Craig, and Franco Mattei. 1991. Measuring internal political efficacy in the 1998 National Election Study. American Political Science Review 85: 1407–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberlo. 2023. Number of Wechat Users; Oberlo. Available online: https://www.oberlo.com/statistics/number-of-wechat-users#:~:text=Number%20of%20WeChat%20users%20in%20China&text=The%20latest%20statistics%20show%20that,at%20least%20once%20a%20month (accessed on 6 April 2023).

- Ran, Weina, and Masahiro Yamamoto. 2019. Media Multitasking, Second Screening, and Political Knowledge: Task-Relevant and Task-Irrelevant Second Screening during Election News Consumption. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 63: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, Alan M. 2009. The uses-and-gratifications perspective on media effects. In Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, 3rd ed. Edited by Jennings Bryant and Mary Beth Oliver. New York: Routledge, pp. 165–84. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, Dhavan V., Jaeho Cho, William P. Eveland, Jr., and Nojin Kwak. 2005. Information and expression in a digital age: Modeling Internet effects on civic participation. Communication Research 32: 531–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smock, Andrew D., Nicole B. Ellison, Cliff Lampe, and Donghee Yvette Wohn. 2011. Facebook as a toolkit: A uses and gratification approach to unbundling feature use. Computers in Human Behavior 27: 2322–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwana, Amrit, Benn Konsynski, and Ashley A. Bush. 2010. Research commentary—Platform evolution: Coevolution of platform architecture, governance, and environmental dynamics. Information Systems Research 21: 675–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, Cristian, and Augusto Valeriani. 2018. Dual Screening, Public Service Broadcasting, and Political Participation in Eight Western Democracies. The International Journal of Press/Politics 23: 367–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, Cristian, Andrew Chadwick, and Ben O’Loughlin. 2015a. Dual screening the political: Media events, social media, and citizen engagement. Journal of Communication 65: 1041–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, Cristian, Augusto Valeriani, Pablo Barberá, Rich Bonneau, John T. Jost, Jonathan Nagler, and Joshua A. Tucker. 2015b. Political expression and action on social media: Exploring the relationship between lower-and higher-threshold political activities among Twitter users in Italy. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 20: 221–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deth, Jan W. 2016. What is political participation? Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez, Alcides, and Robert LaRose. 2015. Social media for social change: Social media political efficacy and activism in student activist groups. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59: 456–74. [Google Scholar]

- Verba, Sidney, and Norman H. Nie. 1972. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Scholzman, and Henry. E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Westerman, David, Patric R. Spence, and Brandon Van Der Heide. 2014. Social media as information source: Recency of updates and credibility of information. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19: 171–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xenos, Michael, and Patricia Moy. 2007. Direct and differential effects of the Internet on political and civic engagement. Journal of Communication 57: 704–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Yinjiao, Ping Xu, and Mingxin Zhang. 2017. Social media, public discourse and civic engagement in modern China. Telematics and Informatics 34: 705–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gender | |

| Male | 46.1% |

| Female | 53.9% |

| Age | |

| Below 20 | 5.7% |

| 20–29 | 34.3% |

| 30–39 | 36.7% |

| 40–49 | 18.1% |

| 50–59 | 3.9% |

| Above 60 | 1.2% |

| Final Education Level | |

| Elementary school | 2.2% |

| Junior high school | 11.4% |

| High school | 30.2% |

| Junior college | 27.5% |

| Bachelor degree and above | 28.7% |

| Monthly Income | |

| None | 8.7% |

| 500–1499 (in RMB) | 13.3% |

| 1500–4999 | 43.4% |

| 5000–9999 | 25.6% |

| 10,000–14,999 | 6.6% |

| 15,000 and above | 2.4% |

| Variables | Measurement Items | M | SD | ɑ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivations | I used a second screen while watching TV programs about “the two conferences” to … [1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree] | |||

| Surveillance | … gain additional information of the topic. | 3.09 | 1.08 | 0.93 |

| … gain extra knowledge about the topic. | ||||

| … know the latest development of the event. | ||||

| … know other peoples’ opinions on the topic. | ||||

| Utility | … discuss the topic in the private setting (with friends, family, or other individuals). | 3.11 | 1.09 | 0.95 |

| … discuss the topic in the official setting (official forums, discussion boards, discussion sections of official social media accounts, etc.). | ||||

| … try to “talk” to the political officials directly by leaving comments or sending message to their social media accounts. | ||||

| … encourage other individuals to express their opinions. | ||||

| … try to guide other individuals’ opinions. | ||||

| Self-presentation | … reflect on my own thinking via learning new information and discussing with others. | 3.12 | 1.09 | 0.92 |

| … express my opinions on the issues. | ||||

| … present myself. | ||||

| Entertainment | … make the TV viewing more interesting. | 3.14 | 1.16 | 0.89 |

| … entertain myself by looking at the funny comments, memes, etc. | ||||

| Second Screening | Please indicate how often you do the following activities using a second screen while watching news about “the two conferences” on TV. [1 = never; 5 = very frequently] | 3.02 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| Search for more information about what I’m watching. | ||||

| Get additional knowledge about what I’m watching | ||||

| Search for others’ opinions and thoughts. | ||||

| Get information about how others react to programs or events I’m watching. | ||||

| React or comment on what others have posted. | ||||

| Repost content related to news or programs that was originally posted by someone else. | ||||

| Encourage others to act. | ||||

| Express my views and opinions related to what I’m watching. | ||||

| Express emotions and feelings that I have while watching. | ||||

| Internal Political Efficacy | How much do you agree with the following statements? [1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree] | 3.29 | 1.20 | 0.93 |

| I believe my opinions could make impacts on the government’s decisions. | ||||

| I believe I am capable of participating in political activities. | ||||

| I know about current political issues very well. | ||||

| Political participation | Please indicate how often during the past 3 months you have engaged in the following activities? [1 = Never; 5 = Very often] | 2.98 | 1.07 | 0.96 |

| Voted in campaigns and elections. | ||||

| Participated in political advertising such as displaying campaign banners, stickers, slogans, and so on. | ||||

| Attended political meetings. | ||||

| Attended political rallies. | ||||

| Donated money to or volunteered in political organizations. | ||||

| Interacted with political officials or organizations in real life (e.g., writing a letter, speaking) to express your needs and views. |

| 95% Bootstrap CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Paths | b | SE | Lower Limit | Upper Limit |

| Surveillance 🡪 Second Screening 🡪 Knowledge 🡪 Efficacy 🡪 Offline Participation | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.50 |

| Utility 🡪 Second Screening 🡪 Knowledge 🡪Efficacy 🡪 Offline Participation | 0.31 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.50 |

| Second Screening 🡪 Knowledge 🡪 Efficacy 🡪 Offline Participation | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Knowledge 🡪 Efficacy 🡪 Offline Participation | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, H. Motivations, Knowledge, Efficacy, and Participation: An O-S-O-R Model of Second Screening’s Political Effects in China. Journal. Media 2023, 4, 861-875. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030054

Liu Y, Zhou S, Zhang H. Motivations, Knowledge, Efficacy, and Participation: An O-S-O-R Model of Second Screening’s Political Effects in China. Journalism and Media. 2023; 4(3):861-875. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030054

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yiben, Shuhua Zhou, and Hongzhong Zhang. 2023. "Motivations, Knowledge, Efficacy, and Participation: An O-S-O-R Model of Second Screening’s Political Effects in China" Journalism and Media 4, no. 3: 861-875. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030054

APA StyleLiu, Y., Zhou, S., & Zhang, H. (2023). Motivations, Knowledge, Efficacy, and Participation: An O-S-O-R Model of Second Screening’s Political Effects in China. Journalism and Media, 4(3), 861-875. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia4030054