1. Introduction

This article takes as its starting point the gradual distancing of journalists from territories considered violent and hostile to the presence of reporters in Brazil (

Nunes 2017). With a main focus on the coverage of urban violence by local television stations, our objective is to understand how assaults, threats and even the murders of professionals in the traditional press have altered routines in newsrooms and to what extent this problem has been addressed via the use of new technologies in news writing. In particular, we consider the use of WhatsApp and encouraging citizen co-production via the use of mobile devices. This dynamic can be both a solution and a problem for journalists and news coverage.

In recent years, cases of serious aggression against journalists have increased substantially, defining limits for journalistic work (

Abraji 2022). In order to safeguard the physical integrity of professionals, TV stations started by adopting safety equipment such as helmets, bulletproof vests and armored vehicles in their coverage of urban violence (

Ramos and Paiva 2007) but ended up prohibiting journalists from entering regions considered hostile to the presence of reporters (

Grupillo 2018). Thus, to a certain extent, this type of coverage came to depend on citizen co-production via the sharing of information, photos and videos from areas of armed conflict. We intend to discuss how, in metropolises such as Rio de Janeiro, for example, this co-production via mobile devices started to supply much of the news, especially that centered on crimes, police operations, robberies, shootings, etc.

In a more general context, information and communication technologies have caused complex transformations in the structure, organization and routines of journalism, having also changed the status of the public from mere news consumers to content producers and distributors (

Bruns 2005;

Ramonet 2012). With the popularization of mobile devices, each person with a smartphone in hand and access to the Internet became able to produce text, sounds and relevant images of journalistic interest. This has become fundamental for journalists to overcome certain limitations and even accelerate the preparation of stories, which are sometimes published before the reporters leave the newsroom and reach the places where the facts occur (

Angeluci et al. 2017). This indicates that the invitation to co-production is ambiguous as it reveals the need to integrate the public into journalistic routines due to the dependence of the content produced by them in specific situations (

Niekamp 2011;

Brasil and Migliorin 2010).

In television journalism, the stimulus to co-production is even more evident. Edition after edition, following any news program will show that the content produced by citizens is completely integrated into the stories, especially those depicting unforeseen events, such as accidents and natural tragedies (

Palmer 2012), that escape the control of organizations (

Tuchman 1972;

Sjøvaag 2011).

In order to take advantage of people’s participatory potential (

Ahva and Wiard 2018), some broadcasters created their own applications such as “Na Rua”, from Globo News TV, while others made WhatsApp an important communication channel with the public. In all news companies, the use of new technologies and encouraging co-production has led to changes in the routine of newsrooms with the emergence of new tasks, new functions and new challenges.

Given this context, in this article, we seek to reflect on the effects of fear and of distancing traditional journalism from the conflicted areas, looking at the communicative possibilities that arise from this reality and how they influence the production of local Brazilian TV news

1 that reports on violence. Although we recognize the particularity of this study, as it was conducted in a specific country, the increase in violence against journalists has been registered worldwide, which puts this issue and its impact on news production at the center of the debate. In this sense, our intention is to contribute to the discussions concerning this theme of fundamental importance.

This article is divided into four parts. In the first and second, we try to place the work in the context of discussions about the boundaries and limits of journalism in the coverage of violence and the way in which citizen co-production fills the gap left by the distance of the press from conflicting territories. In the third part, we explain in more detail the methodology applied in this study. Finally, we highlight the main results observed, seeking to deepen the discussion.

2. Fear and Distancing: Contextualizing the Problem

In Brazil, the year 2022 was considered one of the most difficult for journalists. The most recent survey on violence against press professionals shows disturbing data. In the first 7 months of the year, 66 serious attacks were recorded, including physical assaults, the destruction of equipment, threats and even murders. Compared to the year 2021, these data show a 69.2% increase in violence against journalists compared to the 39 cases of serious aggression recorded that year.

According to the report, among the most emblematic cases of violence against journalists in 2022 are the attack with stones against the reporter Alexandre Megali, the attempt to run over a reporting team from the TV station Globo News (Rede Globo) and the deaths of the British reporter Dom Phillips and the indigenist Bruno Pereira, which had international repercussions. The Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalism (ABRAJI) points to an incisive participation of political agents in violence against professionals in the press, especially the family of former president Jair Bolsonaro

2.

Despite the worsening context in recent years, the problem is not new, especially when we talk about coverage of urban violence in metropolises such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. In general, police coverage requires the use of specific codes of behavior, in addition to the relationship with informants who are not always reliable but are still fundamental for obtaining the “scoop” (

Dias 1992;

Molica 2007). The dependence on police institutions for the elaboration of pieces makes the work of journalists even more complex because, while it makes it possible to obtain information and images of conflicted regions, it also promotes self-censorship. For this reason, police reporting is often viewed with prejudice by a journalistic elite that tends to consider it “second-rate journalism” (

Grupillo 2018, p. 60).

The author point out that from 2002, when journalist Tim Lopes (TV Globo) was brutally murdered during a coverage in the favelas of Alemão in Rio de Janeiro, television stations were forced to adopt security protocols to preserve the physical integrity of reporters and cameramen. The concern intensified years later with the deaths of Gelson Domingues and Santiago Ilídio Andrade, who were both from TV Bandeirantes, during coverage related to urban violence.

This succession of cases led journalist Ricardo Boechat to state on his radio program: “The best news is not worth the smallest risk”

3. Here, Boechat raised the debate on the limits and frontiers of professional coverage in areas of armed conflict in Brazil. Public security sectors tried to establish criteria for journalistic coverage in these regions. The then commander of the military police, Erir Ribeiro, recommended that reporters understand when they are prevented by the police from entering a risk area and obey the guidance

4. The director of the Union of Professional Journalists of the Municipality of Rio de Janeiro (Sindjor) at the time, Rogério Marques, who even admitted that trafficking could not silence the press, defended the proposal of the military police because he believed that there should be a limit to the exposure of journalists in areas of risk.

In the face of all this, the coverage of urban violence in local news gained a new interpretation by journalists.

Grupillo (

2018, p. 69) collected testimonials that demonstrate the fear and concern of professionals in covering urban violence. The testimonials include statements such as “We have to cover everything that happens, it’s the duty of our profession, but I don’t think it’s worth exposing yourself”, “Every press professional when in the middle of a protest and when going up a hill, in a community, in a shootout, whatever it is, he’ll think twice” and “We think five times before doing a public act. In many cases, we do it from the top of the building”. The fear of police coverage has altered professional procedures and routines in television newsrooms.

In Mídia e Violência,

Ramos and Paiva (

2007, p. 99) had already compiled reports, interviews and testimonials from journalists accustomed to police reporting in order to outline an overview of this journalistic genre in Brazil, pointing to problems and challenges. Until the 1990s, journalists were well received in popular communities. In recent years, however, they have come to be seen as non-neutral elements, leading them to face hostile situations. These “borderline situations” led the press organizations to adopt the use of armored cars, helmets and bulletproof vests. In addition to being uncomfortable because it is heavy and hot, this equipment can produce the opposite effect, making journalists into targets that can be mistaken for police officers (

Ramos and Paiva 2007, pp. 102–3).

Therefore, one of the main problems to be faced concerns distancing journalists from areas considered at risk as “journalists in charge of covering security and violence work in fear of becoming news” (

Ramos and Paiva 2007, p. 99). Since the increase in violence against journalists, the entrance of reporters and cameramen into areas of armed conflict has been prohibited, which demonstrates a change in the behavior of professional journalists who began to seek alternative ways of obtaining information and images of urban violence for local news, mainly from citizen co-production via mobile devices.

3. Technology and Citizen Co-Production: A Solution to the Problem?

One way or another, citizens living in regions that have become inaccessible to journalists have created new ways of communicating their needs and problems. The distancing from traditional journalistic outlets, together with internet access and mobile devices, has allowed for the emergence of different initiatives for the hyperlocal communication of violence. The coverage of the invasion of Complexo do Alemão by security forces in 2010, conducted by the local residents themselves, is an example of this. The action was widely publicized in real time via Twitter via the coordination of resident and founder of the local newspaper “Voz da Comunidade”, René Silva. His Twitter page jumped from 180 to 20,000 followers in a few hours

5, which gives us an idea of this communicative potential.

All these dynamics are inserted in a more general context of the progression of people’s access to the Internet and to connected mobile telephone devices. Despite not being universal, in just over 20 years Internet access jumped from 1% to 51% of the population across the globe (

Nunes 2017). In Brazil, for example, 81% of the population accessed the Internet in 2021, and the main connection equipment was the mobile phone

6. That same year, there were 242 million smartphones in use in the country, which represented more than one device per inhabitant. For 75% of Brazilians, mobile devices are not only used more than any other medium to access news but are also used to produce and distribute content of informative interest, including, in particular, events, public services, violence and crime (

Nunes 2017)

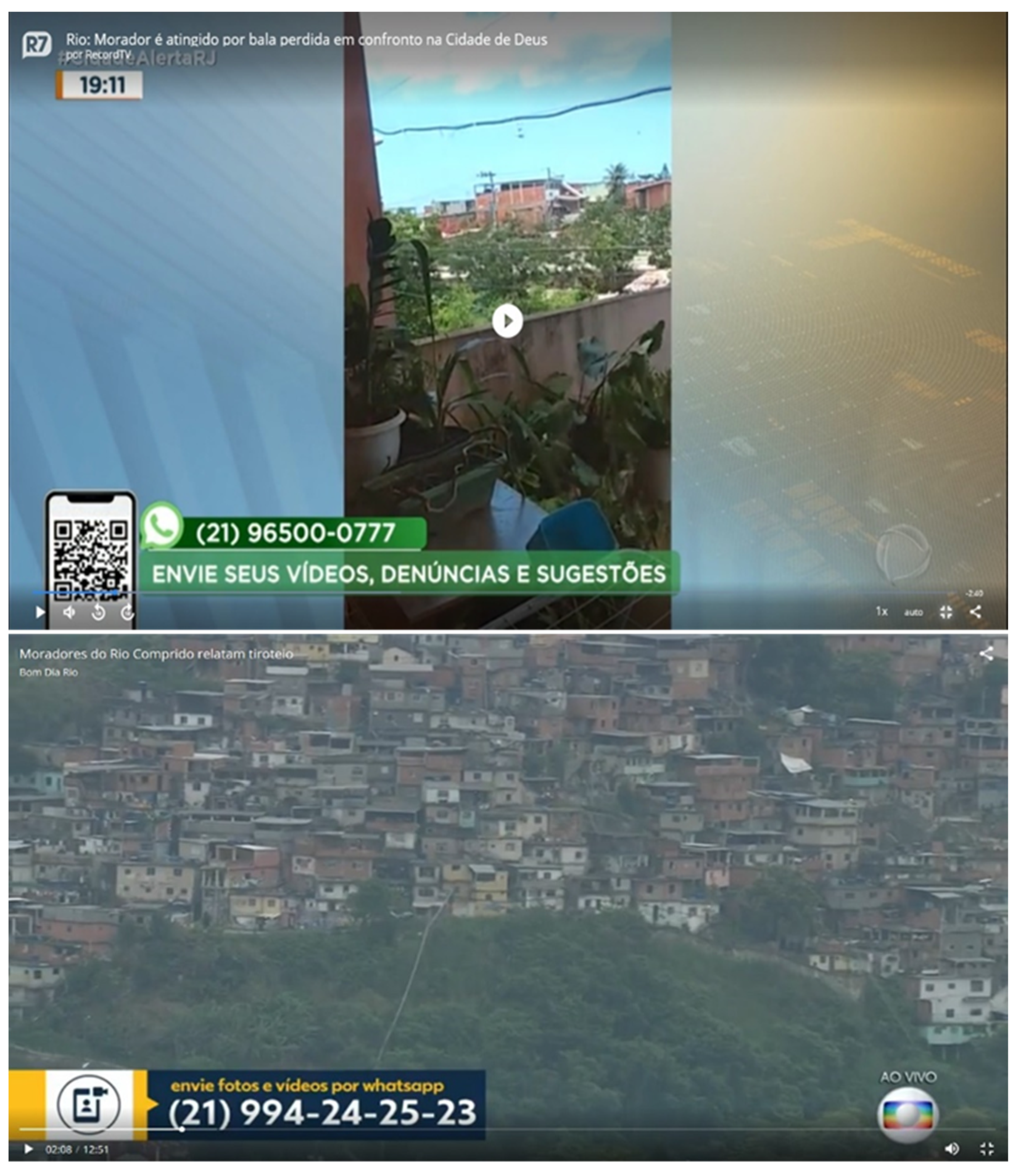

Not coincidentally, this productive potential is valued by local television stations that seek to encourage people’s participation in news co-production by sending information, photos and images. As journalists can no longer be present in certain territories, the public becomes essential for them to be able to cover incidents related to violence such as police operations, shootings and robberies, among others. In part, this explains the implementation of new technologies in the production routines of newsrooms. Via digital social networks, special applications and specific WhatsApp numbers, journalists can maintain closer contact with citizens and obtain raw material for news from the conflict-ridden regions they cannot enter.

Following the logic of major international television channels such as the American Cable News Network (CNN) (

Palmer 2012) or the English BBC (

Allan 2009), Globo News, Rede Globo’s cable TV channel, launched the application “Na Rua” in September 2016. Its main objective is to encourage citizens to send in factual photos and videos. The app went through a test phase in five Brazilian province capitals (Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Fortaleza, Recife and Salvador), where university students and administrators of audiovisual content pages on the Internet were invited to provide information and images for the news programs. One of the first reports made with images sent to the application dealt with an intense shooting in the favela of Rocinha, one of the largest in Latin America, located in the South Zone of Rio de Janeiro (

Figure 1). According to journalist Anna Karina Bernardoni, the tool’s coordinator, the initiative reflects the station’s desire “to let people know what is happening at that moment”

7.

Other stations try to buy content from so-called “amateur videographers” (

Grupillo 2018), but almost all of them have started to use WhatsApp in the production of news about urban violence. In this sense, WhatsApp turned out to be one of the most important tools in the preparation of local news. Its popularization in the world and the reach it has gained in Brazil—among Brazilians who own smartphones, the application accounts for 58% of daily communication—has led journalists to include it in their work routines.

Schuch and Jorge (

2022) highlight the use of this application in the verification, production and sharing of content in the coverage of politics and economics. On the other hand,

Angeluci et al. (

2017) highlight the agility that WhatsApp gives to journalistic productions. The app, which also started to be used to distribute journalistic content, has become an equally important tool for press offices that send suggestions for stories and images of police operations to the media (

Cavalcanti 2016). For

Fort and Branco (

2021, p. 3), the tool transformed the way journalists build news and reach the public, which is why they created a term that seeks to designate the production carried out from the application: “WhatsApp journalism”.

In Rio de Janeiro, more specifically, the citizen app “Onde Tem Tiroteio” (OTT)

8 has also been used as a tool to mediate the coverage of violence, providing journalists with reliable information and images of the regions involved. This co-production, however, can give rise to conflicts related to the authority of the professionals because, although they value and depend on the content provided by the OTT, the editors tend to hide the marks of authorship and the origin of the images in the finalization of the pieces (

Reis and Serra 2022).

As we will discuss further on, our study shows, on one hand, that the use of social networks and applications such as “Na Rua”, “OTT” and WhatsApp are considered by press professionals to be a solution for conducting police coverage. However, on the other hand, the amount and flow of content presents major challenges to journalistic work. Before discussing our results, we will explore the methodological challenges faced in this study.

4. Methodological Challenges

In methodological terms, this work is based on the in-depth interview, a qualitative approach used for the interpretation and reconstruction by the researcher of a certain phenomenon in an intelligent and critical dialogue with reality (

Duarte 2005). It is an “asymmetrical dialogue” in which the researcher seeks to obtain data from a certain interlocutor who presents himself as a source of information. “The interviews seek to explore what people know, believe, hope, feel and desire” (

Veiga and Gondim 2001, p. 5).

For this work, we interviewed 13 journalists (

Table 1), members of a heterogeneous group of professionals occupying different positions in the hierarchy of newsrooms, with different ages and career lengths

9. These journalists work in local news programs in Rio de Janeiro, where the newsrooms of the four main Brazilian television stations are concentrated: Rede Globo, Record TV, Sistema Brasileiro de Televisão (SBT) and Band.

Our purpose was to interview journalists in person, but this work was carried out in the adverse context of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which social distancing became mandatory. Thus, most journalism companies have sought to restrict the presence of researchers and the public in newsrooms.

Therefore, journalists were reached via their digital social networks by sending text messages in which we presented to them the research, the context of its development and the objectives of the study. Intentionally, the first professionals to be contacted occupied leadership positions characterized by decision-making power in the news production processes. These professionals suggested other journalists who could be informants for this study, who, in turn, assisted in the contact with other colleagues. In all, 14 journalists were invited to participate in the interviews. Only one of them, occupying the position of Chief on TV Globo, did not respond to the contacts.

Because of the restrictions mentioned above, all were interviewed at a distance using audio and video transmission and recording platforms, such as Google Teams, Zoom and Skype, between February and March 2021. All participants verbally declared their acceptance of the recordings and signed a term of consent that allows us to use the interviews for scientific purposes. Although all journalists agreed to be identified, we chose to preserve their identities, using nomenclatures such as Journalist 1/Informant 1. The interviews resulted in 12 h, 4 min and 17s of recording.

Although the interviews were made possible by our internet connection, we need to reflect on this process and highlight the constraints we faced in this computer-mediated communication. Most informants preferred that the interviews take place outside working hours, when they were at home and could use their domestic internet package. This condition directly interfered with the quality of the recordings, which were sometimes interrupted by connection failures. Resuming the interviews in these cases was a difficult task as it required not only the interviewer’s ability to retrace the thread of the dialogue but also an effort by the informants to rescue the context of the speeches without losing what was most important in the reasoning. In addition, a computer-mediated interview restricts the field of observation of the entire scenario of composition of the journalists’ speech, including their facial and body expressions, which, together with oral communication, corroborate for an understanding as close as possible to reality.

Despite this, the in-depth interview presents a flexibility that offers the conditions for the interviewee to express their beliefs and feelings about a given subject (

Stokes and Bergin 2006, p. 28). Hence, the technique leads to a greater contextualization and a greater depth of investigation. The advantages of the in-depth interview are (1) the circumstances of unique applicability, (2) the greater control in the selection of the interviewees and (3) the depth and breadth of information it can produce.

However, when, or under what circumstances, are in-depth interviews appropriate? According to

Boyce and Neale (

2006), they are appropriate when the investigator’s interest is to obtain detailed information about people’s behavior or to obtain a more complete picture of a phenomenon or situation and understand why it happened. In this sense, the technique allows for a combination of lived experiences and life stories and an understanding of how effects can produce changes in space and time, the importance of social and historical contexts, and the beliefs and values of individuals, which motivate and justify their actions.

5. Results and Discussion

The journalists interviewed indicate that the departure of traditional media from conflict regions has brought significant challenges to the coverage of violence in local TV news. As

Ramos and Paiva (

2007) suggested, the journalists noticed a change in the way they began to be received in these regions, which ended up demobilizing them from doing on-site reports.

“I would say that about 10, 15 years ago, we were still able to enter communities. The journalist was viewed with a certain amount of respect and managed to enter communities with a certain security. […] This was prohibited both by the owners of the hills, who command the community, and even by the company that saw that there was already a very big risk, not wanting to put reporters, professionals in an unnecessary risk situation. From then on, we started not to enter the communities anymore” (Journalist 6).

In a way, the security protocols adopted by journalistic companies answered the anxieties and concerns of reporters who used to carry out such coverage with concern and the fear of being killed or hit by stray bullets. Before the ban on entry into conflict areas, the decision to continue coverage used to be taken jointly by reporters and reporting chiefs, but this inhibited a tougher stance by journalists to not continue with coverage. Over time, distancing from areas considered at risk led to a greater dependence on citizen co-production. In other words, the use of new technologies, mobile devices and messaging applications became fundamental for journalists to carry out pieces related to violence. We can conclude from the interviews that without these tools and without people sending material, it would be quite difficult to portray most of the local violence events.

“With cell phones with cameras, this has started to become very normal. The residents, the population, start to record these situations. It is through these images that we can gain access to what is happening there. […] We have a WhatsApp that, let’s say without it, today, we wouldn’t be able to make the newscast that we make. Because it is a newscast that relies on viewer interaction. It is a newscast that without the participation of the viewer, it would not be made, especially such a large newscast” (Journalist 6).

Not coincidentally, this productive potential is valued by local television stations that seek to encourage people’s participation in news co-production by sending information, photos and images. As journalists can no longer be present in certain territories, the public becomes essential for them to be able to cover incidents related to violence such as police operations, shootings and robberies, among others. In part, this explains the implementation of new technologies in the production routines of newsrooms. Via digital social networks, special applications and specific WhatsApp numbers, journalists can maintain closer contact with citizens and obtain raw material for news from the conflict-ridden regions they cannot enter.

Therefore, the fear and distancing of journalists from certain territories has led companies to look for other means to “be present” in these spaces, which highlights the use of new technologies, digital social networks and applications (

Figure 2). Tools like “Na Rua”, “OTT” or even WhatsApp end up playing an important role in the production of news because they allow for direct and faster contact with the sources, and this contributes to the collection of data and to obtaining images and sources. This is the main advantage stated by the interviewees, mainly the producers and news chiefs, as part of the content they receive sparks new stories and leads to the unfolding of subjects and special reports.

“It’s 24 h a day, you receive suggestions, you have residents, police, authorities, everyone communicating with us through WhatsApp. We end up receiving a lot of materials, a lot of suggestions” (Journalist 10).

But if, on one hand, the use of WhatsApp can speed up production and diversify the possibilities of stories to be told, on the other hand, this implies a significant increase in the workload of journalists who need to participate in, for example, dozens of message groups and social networks. In addition, new divisions of tasks were implemented in the newsrooms with producers and editors taking turns following up on messages and preparing requests for the authorization to use images.

Two of the stations we surveyed installed software for organizing and filtering texts, audios and videos in order to help journalists in their work. In a third outlet, however, these activities are entirely up to the editorial staff. In a fourth, the function of the “digital producer” was created, in which the journalist is in charge of maintaining contact with the public via social networks in order to produce new pieces.

“As the flow of information has increased, our filter as a journalist has to increase as well. Otherwise, we often fall into a situation of wrong calculation, as has already happened, even on SBT and on several other stations as well. Nowadays, it goes hand in hand with journalism, it’s of paramount importance, we are connected to everything that happens on social networks, in any act that a citizen may be doing, but also with great care in the investigation. But, it goes hand in hand with our work nowadays” (Journalist 3).

Although they may demonstrate dissatisfaction with the workload arising from all these changes, respondents tend not to pay too much attention to the situation because they understand the importance that new technologies and citizen co-production have in the production routines of crime news.

“News reaches you, in a way. […] We have WhatsApp groups for teams, newspapers, journalists and basically every day there: Look, I received this video, I received this video, you have to check it. Or look at this, I received it just now in such a situation. There’s a lot, a lot. We receive a lot, very often and it is still a way for us to be able to report a fact that we might not be able to, we have not been in that situation” (Journalist 7).

In this sense, the implementation of the use of WhatsApp and citizen co-production is fundamental for the elaboration of news. However, this co-production is problematic since it demands more effort from journalists in the verification process. Citizen co-production is not always qualified. Journalists may not clearly know where the information sent came from, and they are not always able to clarify situations with the public. The problem with the verification procedures is one of the most mentioned by the informants, mainly when checking the images sent by the citizens. As videos of violence recorded by the public can circulate repeatedly through different groups, journalists tend to put more effort into verifying the veracity of the images and the match between the recordings and the reported event.

“This is a big problem. This is the biggest problem, the biggest challenge we face. We can’t check everything 100% immediately, immediately check what’s coming. Many times, I have a very good image and I don’t post it on air if I don’t have something to guarantee me that it was here” (Journalist 13).

The intense flow of information and images reaching journalists implies the adoption of new routines and procedures, such as sending videos to government authorities, the Public Prosecutor’s Office and public security bodies. The main problem is that these agencies are not always able to meet the demand of professionals with the speed required by TV news.

“The video will be sent to the military police, civil police, competent bodies depending on what the video is. […] In cases involving even civil and military police, forwarded to the Public Prosecutor’s Office for investigation. The news is aired at the moment when one of these sources, which are considered official, says that either they are going to investigate that information or that the information has already been verified and that such a thing happened” (Journalist 12).

“Because there are times when even the police don’t know what we’re dealing with, you know? Because it’s a lot for the police themselves” (Journalist 5).

It is also necessary to consider that the difficulty of verification may depend on the time of the broadcast of local news. Editors and news chiefs point out that the news programs produced during the night to be shown in the early morning, for example, usually face a scarcity of official sources available at that time, which ends up being a determining factor for the piece not being broadcast or forces reporters and producers to adopt different assessment strategies. In these situations, journalists will try to gauge the number of people involved in the repercussion of a subject on other social networks. That is, the more people are commenting or posting about a particular case of violence, the greater the probability that it is really happening.

“This is a situation that is recurrent and then I think it is important that you report that you still do not have confirmation from the official body, that you have confirmation from witnesses, that you have the speech of those people, the messages of those people who live there. That is something that will interfere with people’s lives. Are you going to stop notifying the population that this is happening because we still don’t have official confirmation?” (Journalist 7).

In short, new technologies and mobile devices began to occupy a prominent place in local television news production, being constantly used by TV stations calling for audience co-production. Tools such as the apps mentioned above constitute an important means of contact between journalists and citizens, the latter being a fundamental agent for the production of pieces related to violence in Brazil.

Maybe this is the reason that researchers such as Lívia de Souza Vieira

10 point out that journalistic institutions continue to be the mediators of events, but that, given the amplification of people’s power of participation, newsrooms began to welcome individual initiatives more effectively, which results in the loss of journalists’ exclusivity in the distribution of news. The boundaries of separation between sender and receiver, until recently clearly demarcated, become diffuse, as one of the consequences of this new relationship (

Sjøvaag 2011).

6. Conclusions

Over the last few decades, in Brazil, the work of local journalists in covering urban violence has undergone significant transformations. First, reporters were no longer seen as neutral individuals and their entry, especially in areas of armed conflict, began to be viewed with distrust by residents. In a way, the murder of journalist Tim Lopes in Complexo do Alemão played an important role in this shift, becoming a watershed in this type of coverage. Thus, although a good part of local television news is devoted to cases of violence, the fear of death or being victims of stray bullets kept journalists away from regions considered dangerous. This contradictory situation ends up dramatizing the coverage of violence and the work of reporters.

Not even the security protocols and protective equipment adopted by TV stations, such as helmets, training and bulletproof vests, were enough to mitigate the fear and concern of reporters and cameramen of being mistaken for police and ending up making the news as the victims themselves. For this reason, the entry of professionals in conflicted regions has been prohibited, making room for the emergence of new communication dynamics that involve the informative production of subjects of journalistic interest by the public using mobile devices connected to the Internet and applications such as WhatsApp.

This potential does not go unnoticed by journalists who, in turn, seek to encourage the sending of material from areas restricted to professional activity. During newscasts, presenters ask the public to send content to a specific number on the station. The testimonies of the journalists heard in this study demonstrate the importance that social networks, instant messaging applications and citizen co-production have gained in the coverage of violence in local television journalism. In a way, the use of tools such as WhatsApp and other smart apps such as “OTT” and “Na Rua” seek to fill in the gaps left by the distancing of journalists from certain territories. Using tools such as those mentioned above, with public interaction journalists obtain information, photos, images and characters to tell and expand their stories, which end up being valued by, in particular, producers and reporting chiefs.

On the other hand, however, this dynamic demands a greater workload from journalists, who now feel obliged to participate in a high number of groups on social networks and messaging applications in order to cross-check and verify information. Professionals also need to adapt and create new production routines. Some of these adaptations involve the division of tasks to follow up on messages, contacting people to confirm information and requests for image authorization and sending public content to official sources. This demands time that local television news stations do not always have.

This indicates that citizen co-production, although fundamental for the coverage of violence, might not be qualified. In other words, journalists value co-production because they know that they cannot be where citizens are, but they tend not to trust the content sent by the public, which raises challenges, especially in verification processes. Hence, journalists feel obliged to participate in many groups, but, in most cases, they are not able to carry out a complete investigation in time for the newscast. This can put journalists in a dilemma in which they are caught between reporting an occurrence of violence that has not been fully verified, “hurting” their feeling of providing a public service, or being “scooped” by colleagues from competing stations.

The interviews show that journalists’ fear and distancing from conflict regions altered their professional routines and changed the local coverage of urban violence on television. Part of this change is considered positive by journalists since technological tools allow them to access content from places where they are not present because they cannot be. However, part of this change is seen negatively, as news chiefs, producers, reporters and editors have to work even harder to verify everything they receive. In this way, technological tools and citizen co-production are seen, at the same time, as a solution and a problem in TV newsrooms.