Abstract

Fake news and misinformation are a menace to the public sphere, democracy, and society with sometimes irreversible consequences. Journalists in the new era seem not to be able or willing to play their traditional role of gatekeeper and social media have made the problem even more intense. The need for truth is unnegotiable in modern democracies. Nevertheless, non-true stories and misinformation dominate media outlets with severe consequences and negative impacts on societies all over the world. Fact-checking platforms based on crowdsourcing strategies or automated digital websites might be the answer to a problem that is escalating. Initially, in order to tackle such a severe problem, researchers and experts have to monitor its characteristics. Very few research attempts have been conducted in Greece on fake news, its characteristics, origin, and impact. This dissertation scopes to map the characteristics of fake news and misinformation in an EU country such as Greece, based on the findings of “Ellinika Hoaxes” a fact-checking platform that uses in combination professional fact-checkers and crowdsourcing strategies in collaboration with Facebook. The findings shape new perspectives on the nature of misinformation and fake news in Greece and focus on new communication and fact-checking models.

1. Introduction

News and media, in their gatekeeper function, is expected to play a pivotal social role in providing relevant and accurate information during crisis situations. In their coverage, news media and journalists are acknowledged as being capable of shaping the evolution and magnitude of a crisis and its consequences. Media make information public and so add to the collective knowledge of what is going on (Van der Meer et al. 2016).

The digitization of news has challenged traditional definitions of news. Nowadays, social influence and information diffusion are strongly linked with the World Wide Web, social media platforms, and social participation. For more than twenty years, scholars have tried to explain the role of the new technologies in the participation of the public in crucial events, such as demonstrations and collective actions (Karyotakis et al. 2019).

Online platforms provide space for non-journalists to reach a mass audience. The rise of citizen journalism challenged the link between news and journalists, as non-journalists began to engage in journalistic activities to produce journalistic outputs, including news. Citizen journalists were initially confined to blogging. Eventually, social media offered a wider platform for non-journalists to engage in journalism. Through their social media accounts, users can post information, photos, videos, and narratives about newsworthy events they witness first-hand. Journalists have also followed the audience and increased their presence on social media (Tandoc et al. 2017).

The rise of fake news highlights the erosion of long-standing institutional bulwarks against misinformation in the internet age. Concern over the problem is global. However, much remains unknown regarding the vulnerabilities of individuals, institutions, and society to manipulations by malicious actors. A new system of safeguards is needed (Lazer et al. 2018); but where does fake news come from and where can we meet the phenomenon? Which are the media outlets that are more prone to fake news? Very few researches have been conducted concerning the Greek mediascape. This study tries to reveal the characteristics of fake news and non-true stories in the Greek public sphere. Furthermore, promising emerging fact-checking platforms based partially on crowdsourcing, such as “Ellinika Hoaxes,” shape different perspectives in the Greek mediascape and fake news control.

2. Literature Review

The media can play multiple roles that are explained in different ways. From surveillance of the environment to the creation of the collective imagination, from social control to entertainment, and from commercial enterprise to the industry of consciousness, multiple facets appear when we try to grasp the reality of the media. These changes make us reflect often on the complexity of the media’s method of operation. In normal times, media are integrated into the social fabric and nearly go unnoticed. However, in times of crisis, the media are more exposed and follow a cycle of behavior that begins with a step-by-step account of the facts and their development that leaves no detail omitted. […] Although the communication channels available today are improving worldwide interactions, the dissemination of uncorroborated information is affecting the content’s credibility adversely (Liu et al. 2020).

News media brands can be considered as signs of credibility and quality, designed to communicate traits and feelings, and to enhance the product value. A brand can be associated with previous product experience and can create expectations for future outcomes. Keeping in this vein, a news media brand serves as a construct that reflects emotional, cognitive, stylistic, conscious, and unconscious indications for a news medium. The significance of news media brands was stressed by Marshall McLuhan, in his popular quote, “the medium is the message”. News media brands function as a formative trait of media messages and affect the process of news elaboration. In particular, news media readers encode, store and retrieve better the news that is offered by a specific media brand, rather than the news provided by non-branded media. Credible news media brands trigger stronger arousal responses, which in turn improve information storage and retrieval efficiency (Riskos et al. 2021).

When news offices started to connect to each other via wire, the authenticity of information became a concern. Editors did not really know whether the news coming in through the wire was true or not. They could try to infer authenticity based on the source the news, but still the concern remained: is this piece of news that just came over the wire true or not? Although the concern was there, the editors usually managed to find ways to mitigate it and reduce the intentional misinformation to the minimum possible: after all, the amount of news that came over the wire and could potentially be misinformation was not that large. Unfortunately, the “tsunami” of social media engagement that has swept our lives over the past decade practically exploded in a proliferation of misinformation, including the associated distribution of fake news (Paschalides et al. 2019).

The dominant incentive for journalism’s participation on Silicon Valley platforms is largely coercive, based on fears that competitors will contribute news content to platforms or that audiences will ignore publishers who do not. Central to this concern is a realization that Facebook and other platforms are the only way news organizations may “reach a wider public, in particular younger people who do not normally come direct to their sites or apps”. Managers for prestigious US and European publishers actively seek to distribute content on platforms, but also worry about loss of control over news content. Publishers believe they must maintain good relationships with Facebook and Google or risk being penalized within algorithms governing content distribution. Remunerative incentives apply to journalism to the extent that publishers rely on a two-sided market of audiences and advertisers. Platforms provide some material incentive for journalism by referring users to publishers’ websites, where audience attention can draw in advertising revenue; or to the extent they provide audience data that help publishers gain revenue. However, no “significant transfer of wealth from technology companies to news organizations” supporting quality journalism has occurred (Vos and Russell 2019). However, this seems to be changing as new journalistic models of verification and fact-checking emerge such as the “Ellinika Hoaxes” platform, described in this dissertation.

2.1. Fake News, a World Menace

In the era of information overload, restiveness, uncertainty, and implausible content abound; information credibility or web credibility refers to the trustworthiness, reliability, fairness, and accuracy of the information. Information credibility is the extent to which a person believes in the content provided on the internet. Every second of time passes by millions of people interacting on social media, creating vast volumes of data, which has many unseen patterns and behavioral trends inside. The data disseminating on the web, social media, and discussion forums have become a massive topic of interest for analytics as well as critics as it reflects social behavior, choices, perceptions, and mindsets of people. Connectivity on the internet provides people a vivacious and enthusiastic means of entertainment as well as refreshment. A considerable amount of unverified and unauthenticated information travels through these networks, misleading a large population. Thus, to increase the trustworthiness of online social networks and mitigate the devastating effects of information pollution, timely detection and containment of false contents circulating on the web are highly required (Meel and Vishwakarma 2020).

One of the most common terms for misleading non-true stories is “fake news”. In the context of globalization, the mass media are undergoing fundamental changes in terms of structure, form, and content. Within today’s media landscape, theorists and practitioners of journalism are increasingly often confronted with the phenomenon of fake news, i.e., false, in most cases sensational, information spreading under the guise of news. A number of researchers (Baym and Jones 2013; Kooijman 2008; Becker 2018) claim that satire and parody, as a form of digital art, can also be categorized as fake. The definition can embrace a huge variety of forms of misinformation for commercial, political, or entertainment purposes. In any case, the main objectives of fake stories are to manage public opinion, control the social situation, form a specified impression, or justify someone’s policy and actions. The phenomenon of fake news has become increasingly popular in recent years. Such an intense interest is due to the fact that the dissemination and the use of false information are so widespread today that, according to a number of public figures, it can represent a serious threat. The elimination of technical barriers to disseminating information increases the importance of other aspects of this process (Berduygina et al. 2019).

“Fake news” is defined as fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent. Fake-news outlets, in turn, lack the news media’s editorial norms and processes for ensuring the accuracy and credibility of information. Fake news overlaps with other information disorders, such as misinformation (false or misleading information) and disinformation (false information that is purposely spread to deceive people) (Lazer et al. 2018).

The term ‘fake news’ has emerged as a global construct among leaders, media professionals, and consumers of media content, capturing a new trend of doubt and disbelief towards mainstream media organizations which, in the past, maintained a capacity to establish the salience of news stories while advancing dominant agendas. Some of this capacity is currently claimed by alternative, hybrid mediated entities while influencing users’ perceptions and behaviors. Indeed, the media’s ability to establish a mass consensus about the significance of news topics has been blurred by the advent of hybrid media entities that advance various types of content while contributing toward public fragmentation (Maniou et al. 2020).

In areport on fake news and online disinformation by the independent High- Level Group of Experts of the European Commission, the term “fake news” is deliberately avoided (HLEG 2018). As the HLEG underlined, the term fake news is inadequate to capture the complex problem of disinformation, which involves content that is not actually or completely “fake” but consists of fabricated information blended with facts and practices that go well beyond anything resembling “news” to include some forms of automated accounts used for astroturfing, networks of fake followers, fabricated or manipulated videos, targeted advertising, organized trolling, visual memes, and much more. In addition, the report uses the term ‘disinformation’ to address all forms of false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented, and promoted to intentionally cause public harm or for profit (Mavridis 2018).

Through the discipline of verification, journalists determine the truth, accuracy, or validity of news events, establishing jurisdiction over the ability to objectively parse reality to claim a special kind of authority and status. Social media question the individualistic, top-down ideology of traditional journalism, subverting journalism’s claim to a monopoly on the provision of everyday public knowledge. […] The notion of the journalist as the verifier of news and information is at the core of journalism as a system of knowledge production and central to a structural claim to expert status and statement of authority. Zelizer (2004) argues journalism’s presumed legitimacy depends on its declared ability to provide an indexical and referential presentation of the world at hand, and also states that journalists distinguish what they do from other forms of public communication by claiming an ability to interpret and represent reality (Hermida 2012).

2.2. Crowdsourcing

A proposed solution to the problem of non-true stories could be crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing is a form of collective online activity in which a person or an institution or a nonprofit organization or a company proposes, through an open invitation, to voluntarily take up a job (Estellés-Arolas and González-Ladrón-de-Guevara 2012).

Jeff Howe (2006, 2008) has distinguished four types of strategies for crowdsourcing:

- Crowdfunding (fund raising)

- Crowdcreation (the crowd creates)

- Crowdvoting (collective vote)

- Crowdwisdom (collective intelligence)

Crowdsourcing is a way for journalists to fill gaps in their knowledge. A metaphor for illustrating the mechanism in practice is fishing with nets. By crowdsourcing, journalists cast their nets into the water. The net is larger and wider than in a traditional journalistic knowledge search, which involves the journalist calling potential sources one by one. In crowdsourcing, the journalist’s call for information goes out to a massive number of people simultaneously, and thus, can result in an effective discovery of knowledge. Crowdsourcing can be particularly useful to journalists who are new to a topic or to news journalists who are not covering their regular beat, because news journalists are time-pressured for finding relevant information very fast (Aitamurto 2015).

When journalists use crowdsourcing in journalism, they open up the journalistic process to the public. Crowdsourcing thus can be considered an open journalistic practice. In open journalism, openness comes into play in several parts of the journalistic process. The process can be open to the public in the beginning, like in the previous examples, or it can also be open later in the process, when the journalist wants to source more information from the crowd. The journalist can also ask for ideas for interviewees, subjects of visualizations, and so on. However, in open journalism, the journalistic process is accessible to the public only in certain parts, and the process is never fully open (Antonopoulos et al. 2020b).

The most common understanding of participatory journalism could be formulated as the idea that digital technologies enable the audience to get involved in making and disseminating news. News organizations and journalists around the world experiment with new, technology-enabled forms of audience participation (Borger et al. 2013).

Citizens of this information age are provided with a plethora of opportunities not only for accessing information such as news but also for producing and sharing such information themselves. This led to the beginning of the participatory journalism era. Participatory journalism is any type of news work in which professional journalists and citizens collaborate with each other to produce news. The networked environment makes possible a new modality of organizing production: radically decentralized, collaborative, and non-proprietary; based on sharing resources and outputs among widely distributed, loosely connected individuals who cooperate without relying on either market signals or managerial commands (Antonopoulos et al. 2020a). Crowdsourcing in Journalism is defined as an invitation for the crowd to participate in the journalistic processes in various ways, by submitting knowledge, sharing opinions, or sending photos. Crowdsourcing in journalism resulted in efficient knowledge search and discovery in all the cases. In several cases, the crowd provides leads and tips that the journalists would most likely not have discovered otherwise (Lamprou and Antonopoulos 2020).

Traditionally, mass media, such as television and newspapers, which carry information from authorized sources, played the role of transmitting official information. However, over the past few decades, the rise of the Internet, and in particular of social media, has substantially changed the media environment. These media challenge the role of the mass media by providing effective channels to reach alternative sources of information (Ferreira and Borges 2020). Factors that constitute markers of a crisis in professional journalism include:

- A precipitous drop in newspaper circulation numbers and advertising revenues (both classified and print), that has been accentuated by economic downturn since the global financial crisis of 2008;

- A dramatic fall in share prices for commercial media businesses, many of which acquired high levels of debt in the 2000s, and which appear to be struggling to develop new business models for the internet economy;

- A shift in the “attention economy” of media users, who deal with media proliferation by seeking multi-media combinations, and spending less time consuming any single media product or service

- A crisis of authority for professional journalism arising from the shift from the ‘high modernist’ era of crusading investigative journalism and one-off features towards the 24-h news cycle and the need to continuously reproduce news around familiar themes and formats;

- A growing public distrust of journalists who are increasingly being seen as the conduits for material provided to them by well-funded political, business and other special interests (Flew 2009).

Despite the very different nature of these two types of media (conventional media and social media), they are highly interconnected. Their combined and permanent use sustains and, to a large extent, deepens the dependence of individuals on the media system (Ferreira and Borges 2020).

Objectivity, or impartiality or neutrality, is one of the core norms of journalism. Journalists are supposed to report the facts in as fair and balanced a manner as possible, although absolute objectivity is impossible to attain. According to the norm of accuracy, journalism should provide verified facts. The norm of transparency instructs journalists to communicate ethical choices to the public and transparency about the production process. The norm of autonomy is about maintaining journalistic control over the content without dependencies or conflicts of interest that could bias the reporting. However, advertisers, readers, and political authorities, among others, continuously exercise power over newspapers’ editorial decisions. The two fundamental features of crowdsourcing—its capacity to reach a large crowd and its low cost—can help journalists in their pursuit of these aspirational norms. Crowdsourcing can support the norms of neutrality and objectivity by helping journalists efficiently solicit knowledge from a large number of sources. This access to information that would otherwise be unavailable can lead to more accurate reporting. Studies on crowdsourcing in journalism show that by deploying crowdsourcing, journalists can effectively conduct investigations into important and timely societal issues. The large pool of informants increases the chances that journalists find knowledge that would otherwise remain hidden (Aitamurto 2019).

News organizations are not looking only for journalists: they are also looking for data journalists, social media managers, graphic designers, podcast producers, engineers, and so on. Nowadays, to produce journalism a professional may also be something else. Additionally, this concerns not only working roles but also working conditions: “precarious working arrangements have come to determine news work, even for those who in fact still enjoy a contracted job with a salary and benefits.” People who produce journalism—or at least some legitimately recognizable form of it—are today very different from those of the past in terms of their working conditions, settings, level of professionalization, and so on. Salaried journalists work alongside freelance journalists, dialogue with citizen journalists, and write pieces about news and information provided by people posting it online with no intention of doing journalism but, eventually, ending up in the process nevertheless. […] It is necessary also to understand whether the concept of news has changed, and whether this influences a new, hybrid, mode production of news stories. However, most importantly, we need to assess whether these changes have become the new routine of journalism, and what journalists take for granted, that is, the third layer: the discursive construction of journalism itself (Splendore and Brambilla 2021).

2.3. Fact-Checking in Journalism

Fact checking in the U.S. rests on an assumption that the public will trust journalistic objectivity, but challenges the idea that journalists should report rival claims without evaluating them. For decades, Western journalists argued their work revolved around core ethical values, at the center of which was the value of objectivity, to be “free from values and ideology” (Haigh et al. 2017).

Nonetheless, despite the elusive nature of fact-checking criteria that apply to journalistic practice and the fact that professionals often use fact-checking as a strategic ritual, in recent years, many of the actions to fight disinformation from the journalistic practice have been oriented to the improvement of fact-checking procedures. Since healthy democracies need a healthy media and quality journalism, the search of solutions to the weaknesses of journalism in terms of verification have appeared in the form of fact checking, which offers innovative alternatives that combine the technological and communicational dimension to deal with disinformation. The purpose of fact checkers and fact-checking organizations is to increase the knowledge through the research and dissemination of facts mentioned in statements, either published or recorded, made by political figures or any other individual whose opinions have an impact on the lives of others (López-García et al. 2021). The challenge is that the human fact-checkers frequently have difficulty keeping up with the rapid spread of misinformation. Technology, social media and new forms of journalism have made it easier than ever to disseminate falsehoods and half-truths faster than the fact-checkers can expose them. There are several reasons that the falsehoods frequently outpace the truth. One reason is that fact-checking is an intellectually demanding and laborious process. It requires more research and a more advanced style of writing than ordinary journalism. The difficulty of fact-checking, exacerbated by a lack of resources for investigative journalism, leaves many harmful claims unchecked, particularly at the local level (Hassan et al. 2015).

Nevertheless, there is considerable interest in fighting online disinformation. Major platforms such as Facebook prioritize trustworthy sources and shut down accounts linked to disinformation. Some users of these platforms avoid fake news with tools such as News Guard and Hoaxy and websites like Snopes and PolitiFact. These services rely on manual fact-checking efforts: verifying the accuracy of claims, articles, and entire websites. Efforts to automate fake news detection generally point out stylistic biases that exist in the text (Zellers et al. 2019).

Designing platform-based interventions to provide users with signals on content and source quality is a potentially effective way to combat mass-scale misinformation. Fact-checking labels can reduce the impact of exposure to misinformation (ex) on corona virus vaccine attitudes. We define a fact-checking label as a tagline message that labels a piece of information as false. An important factor in determining fact-checking labels’ effectiveness involves determining to whom the label is attributed, in that the effect can depend on the audience’s subjective evaluation of its source credibility (Zhang et al. 2021). The discipline of verification has long been a core pillar of journalism, but the approaches to and effects of journalistic verification vary depending on the historical, cultural, and technological contexts. Historically, in both democratic and authoritarian states, the establishment of journalism as a profession required its own authority and standards for information verification. The proliferation of new participatory communication technologies, in particular social media, has significantly reshaped the authority of journalistic verification. In a digital media environment, practices of information verification have become increasingly decentralized (Zeng et al. 2019).

Fact-checking ties new reporting techniques to an appeal to longstanding journalistic values. Journalists active in the fact-checking movement often present it as a response to so-called “he said, she said” news reports, arguing that the new genre is truer to journalism’s mission as a truth-seeker and political watchdog (Graves et al. 2016).

Aggregated fact checks might produce better results in this regard but would substantially reduce the number of weekly or daily posts, thereby also reducing the salience of the fake news threat. Fact-checking sites shape the meta-discourse on the problem: topics and issues addressed by individual posts are less relevant in comparison to the implied message that fake news is an omnipresent problem requiring constant vigilance. As an increasing range of online falsehoods is considered dangerous, the truth may gradually emancipate itself from other protected interests (Schuldt 2021). In the US and Europe, different types of fact-checkers have emerged. Generally, two models of fact-checkers are distinguished: the ‘newsroom model’ and the ‘NGO model’. The newsroom model contains fact-checking organizations affiliated with an established media company. Although only a minority of fact-checkers in Europe belongs to this model, these fact-checkers often have a wide reach. In Germany, for example, the public broadcaster ARD operates its own fact-checking website. The NGO model, in contrast, involves fact-checkers that operate independently of traditional newsrooms. Those organizations are free of the editorial and business constraints of established media outlets but lack the editorial resources and reliable audiences. However, some of these organizations have managed to establish themselves in national media markets. Those outlets are completely independent, are projects of established NGOs, or are linked to universities. Such a case is the “Ellinika Hoaxes” fact-checking platform which is funded only from Facebook due to its high performance in detecting non-true stories (Lamprou and Antonopoulos 2020).

2.4. Fake News in Greek Mediascape

Distributing misleading information on Greek media, social media, and the Internet is not a new phenomenon. In her recent study about propaganda on Greek media, Patrona (2018) discusses the historical framework of the Greek case and emphasizes the fact that in Greece there has always been misleading information, false facts, and fake news in the media. For instance, by analyzing the discourse of the Greek media, Patrona comes up with the conclusion that there is a common pattern which leads to the production of fake news: Greek media present conversations as news and instead of using data in their reports, opinions are preferred. Poulakidakos and Armenakis (2014) studied the Greek media discourse in relation to the economic crisis of 2010 and they point out cases where media in Greece presented fake news with misleading information in order either to promote a specific political propaganda or to gain money. By analyzing the discourse of the most prominent Greek media, they conclude that popular Greek online newspapers, such as tanea.gr and enet.gr, made use of sentimental propagandistic methods and they generated misleading and fake news (Mavridis 2018).

Lamprou and Antonopoulos (2020) take this research one step beyond examining Greek mediascape and fake news presence and origin. The results of their research claim that the percentage of non-true stories detected in portals/blogs is much higher than those detected in traditional media websites such as newspaper websites and TV station websites. Traditional media seem to retain their credibility in comparison to portals and blogs according to the findings of the study. Nevertheless, the comparison might be deceiving. Through qualitative case analysis, severe cases of misinformation were highlighted (though much fewer) in professional traditional media mostly on hard news (Foreign Policy, Pseudoscience on Health issues, Terrorism). According to the researchers, “Ellinika Hoaxes” fact-checking platform, based partly on crowdsourcing strategies, seems to be effective in detecting fake news of all kinds even in the most prominent and respected media outlets. Thus, although professional media in Greece seem to retain their trustworthiness in comparison to new media, portals and blogs, fake news seems to have penetrated professional journalism significantly. This fact may raise questions for different ways of monitoring news and its credibility and accuracy.

2.5. Major Social Networks & “Ellinika Hoaxes” Fact-Checking Platform

American fact checkers, such as PolitiFact, typically take a claim from a political speech or opinion piece and ask academic experts to evaluate it. The result is summarized with a ranking while “True” and “False are options claims are often ranked as “Mostly True” or “Mostly False” (Haigh et al. 2017).

One of the most promising attempts of fighting fake news in Greek public sphere is Ellinika Hoaxes. E.H. is a platform that mainly “hunts” non-true stories but also uses crowdsourcing strategies in order to detect not only fake but also low-quality content. The fact-checking platform commenced in 2016, an idea of Thodoris Daniilidis, investigating the news circulating on the Greek internet and highlighting those that are not true.

Laura Bononcini, Director of Public Policy of Facebook in Southeast Europe, officially stated on May 2, 2019 the beginning of a partnership with “Ellinika Hoaxes”. Major platforms like Facebook have taken steps to help citizens access verified information, connecting those to related procedures and repositories. Since, fact-checkers have played an important role in this battle by critically evaluating claims, and thus informing citizens about their integrity and credibility. These groups of media experts are usually equipped with abilities and methods to identify unverified stories and to look for evidence that raises neutrality (Katsaounidou et al. 2019). Facebook started in December 2016, collaborating with organizations and fact-checking teams all over the world to reduce the spread of fake news on its platform. All partners have been audited and certified according to the standards of the International Fact-Checking Network. The platform validates cases of non-true stories. According to the platform’s website, “Ellinika Hoaxes” encourages readers to participate in the fight against non-true stories. For this reason, the platform uses crowdsourcing strategies and techniques and it is always open to suggestions, remarks, corrections, submission of topics for research, etc. Users’ participation through the submission of proposals is one of the basic rules for choosing topics according to the platform.

Examining the methodology used by the platform, it is quite obvious that a combination of employed fact-checkers with crowdsourcing strategies is used. According to the “Elinika Hoaxes” website, “Regarding the submission of research topics, we urge our readers to include at least one URL of the material in question with a brief description, while also giving the option to attach relevant files (e.g., photos)”. According to the platform’s claims, “some readers also send us preliminary research or suggestions regarding the research the platform could pursue, practices that are welcome but not necessary. In any case the platform declares that users’ participation is of the utmost importance”.

Regarding the priority of exploring new issues, the two main relevant factors that determine it are the following:

- (a)

- Dissemination—a post on Facebook with hundreds of notifications or a news item that has been published from a wide range of pages (especially if some are widely considered credible) is considered more urgent than a post on a relatively unknown blog.

- (b)

- The severity of the effects of misinformation: an article with potentially inaccurate medical claims, especially if it can lead patients to suspend their approved treatments, is considered more urgent than an article about a humorous joke.

According to Lamprou and Antonopoulos (2020) “E.H.” platform does not produce original news stories and it is not a journalistic media outlet. It is merely a fact-checking website funded by Facebook, combining fact checkers employment and crowdsourcing strategies in order to bust fake news that emerges in the Greek public sphere.

“Ellinika Hoaxes” utilizes a team of professional fact-checkers who run the fact-checking procedure based on information that comes from the crowd through an open call: E.H. encourages readers to participate in the fight against fake news. For this reason, the platform is always open to suggestions, remarks, corrections, submission of topics for research, etc. Citizens’ participation through the submission of proposals is one of the basic rules for choosing their fact-checking topic. All major crowdsourcing strategies of Howe’s theory are used: Crowdcreation, Crowdvoting, and Crowdwisdom except Crowdfunding.

The platform uses the following fact-checking procedure (Lamprou and Antonopoulos 2020):

The crowd proposes potential non-true stories and fake news cases through the “Ellinika Hoaxes” website or official Facebook page. Then, professional fact-checkers of the platform take action:

- Step 1: Potentially suspicious material is identified.

- Step 2: Content analysis: The fact-checking team contacts initial sources.

- Step 3: Audiovisual research: To make sure whether audiovisual material is really related to the article’s allegations.

- Step 4: Examination of scientific studies in cases of pseudo-scientific claims.

- Step 5: Communication with other fact-checking groups/organizations.

3. Methodology & Analysis

Researchers and stakeholders, in order to deal with the phenomenon of fake news and misinformation but also with low-quality news content, it is necessary to map their origin. Lamprou and Antonopoulos (2020) highlighted the Greek mediascape tactical situation and suggested that although traditional media outlets seem much more trustful than portals and blogs, a significant amount of non-true stories penetrates traditional media outlets. Only if we know where and how will we encounter non-true stories of all types can the phenomenon be dealt with effectively and this consists the main scope of this dissertation.

Few research efforts have been made in Greece in order to demonstrate both the quantitative and qualitative elements of the origin of non-true stories. This dissertation hopes to further research the findings of Lamprou and Antonopoulos (2020) and to give an answer as to where we can find misinformation and fake news, what they look like, and whether they are popular and influential or not. Also, the use of a fact checking platform as a basis of reference for this research may give another perspective on how contemporary journalistic communication models transform given more decentralized standards.

Therefore, in order to answer those questions, it is important to know more precisely where we will encounter non-true stories, but also which are the website categories that display non-true stories more often. Thus, it was deemed appropriate to use the quantitative research in combination with the walkthrough method recording of the news websites that displayed fake news. In addition, qualitative research was selected in order to confirm the findings of this dissertation. The quantitative part of this study focuses on monitoring and analyzing the characteristics of non-true stories busted by the Greek Facebook-approved fact-checking platform “Ellinika Hoaxes”.

3.1. Quantitative Part of the Study

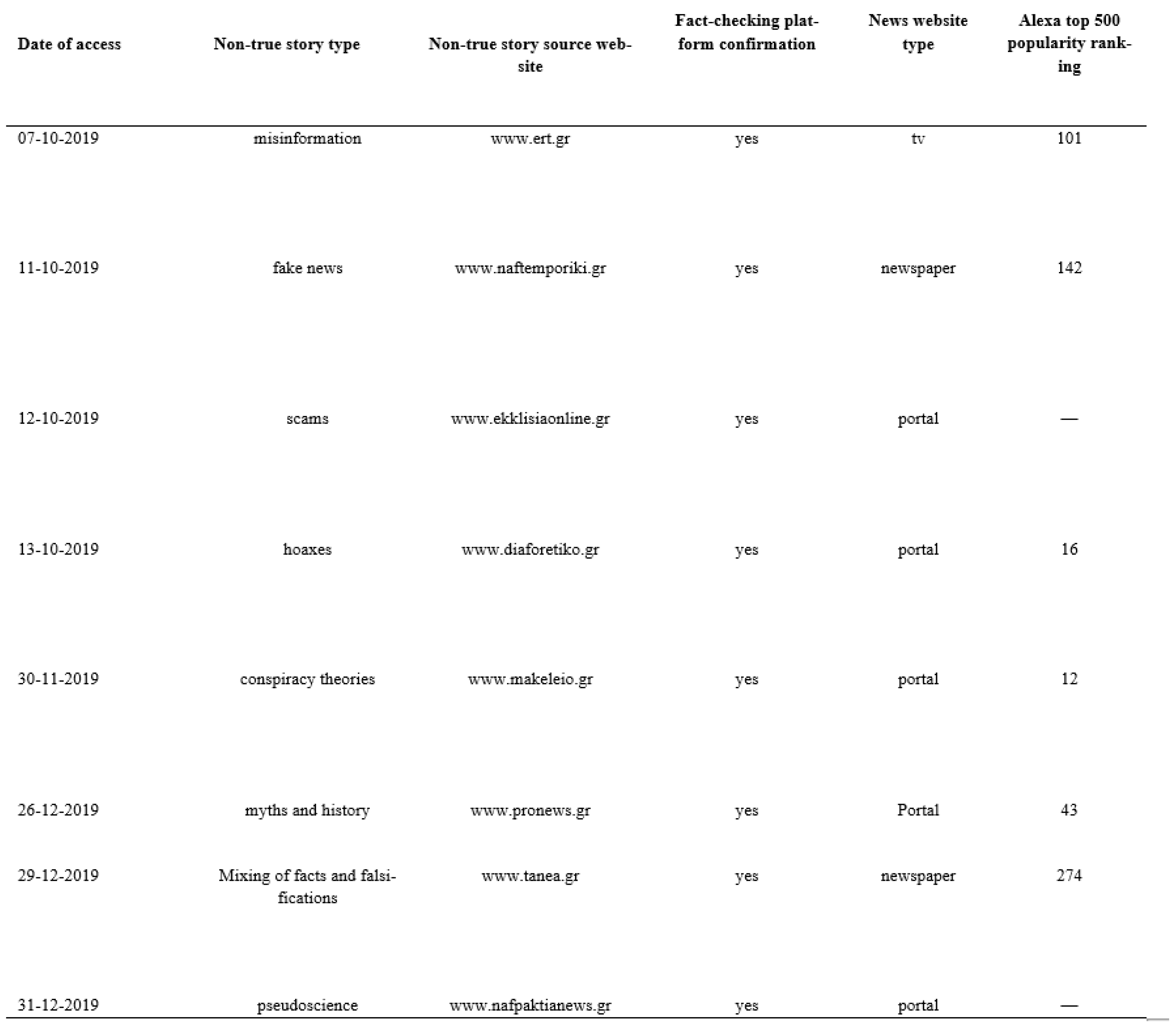

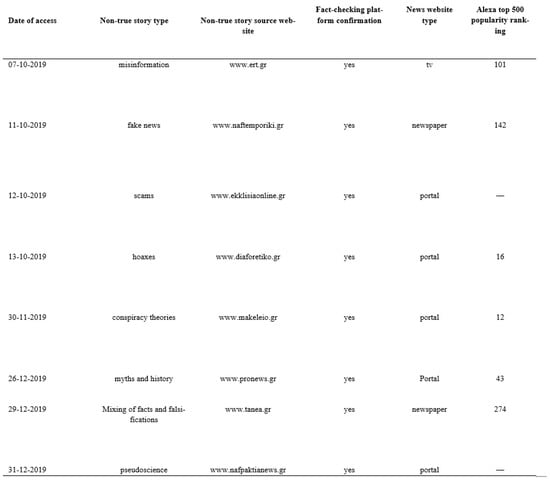

Researchers recorded all the non-true stories refuted by the “Ellinika Hoaxes” platform between 1 October 2019 and 31 December 2019 using the walkthrough method utilizing the MS Excel software for statistical analysis. Non-true stories were categorized according to the classification made by the platform itself as displayed in Table 1. Thus, specific categories of busted stories were recorded such as Misinformation, Pseudoscience, Scams, Fake News, and Hoaxes, Mixing of Facts and Falsifications, Conspiracy Theories, Myths & History. The classification of non-true stories in the above categories is an innovation of the fact-checking platform based on everyday experience in encountering non-true stories and their practical distinction. This is not a classification based that much on scientific patterns and literature but rather a practical one that is applicable in the Greek everyday experience in encountering non-true stories and helps readers to access them and find them. Though, this dissertation introduces this kind of non-true stories practical classification as a pattern for researchers and non-true stories busters and fact-checkers. The basic distinction according to the official website of the fact-checking platform (Ellinika Hoaxes 2019) of the above non-true story categories are the following: “Misinformation” has mostly the meaning of propaganda and disinformation. A characteristic example of this category is a non-true story that claims that the Minister of Defense of Turkey published on his Facebook account a series of maps of Turkey, which include Greek territories. “Pseudoscience” as a category includes mostly non-true stories based on false scientific information, breakthroughs, and dangers. A characteristic example of this category is a non-true story that claims that the use of lemon peel can treat a variety of diseases, including cancer. The allegations, however, are false. “Scams” as a category refer mostly to false appeals for help or false investment opportunities or allegations that can lead readers to money loss. A characteristic example of this category is a false allegation that a little girl, Eva, suffers from sarcoma and her parents call for financial support to a bank account and further notification of her case. “Fake news” is a more general and broad category and includes lots of false allegations, but not necessarily intended ones. A characteristic example of this category is the presentation of a sculpture carved from a Colombian artist with a false allegation: “This street sculpture was designed by a father who lost his wife and his unborn child by a drunk driver”. “Hoaxes” as a category includes mostly those non-true stories which include deceiving characteristics in an ironic way but this not always the case. An example of this category is a false allegation which claimed that the dog depicted was abandoned and was available for adoption. “Mixing of Facts and falsifications” is another category that refers to non-true stories that are not completely false. These are potentially more dangerous because they include a part of the truth. A characteristic example of this category is the allegation that bees are the most important animals on the planet and humans cannot live for more than four years if bees are extinct. Indeed, bees are extremely important but the allegation is partly false. “Conspiracy theories” is another category that refers to allegations that give explanations for events or situations that invoke a conspiracy by sinister and powerful groups. A characteristic example of this category is the false allegation that Greece was attacked by “Directed Energy Weapons” and the deadly fire in the “Mati” region happened due to them. “Myths and history” is another category which mostly refers to misrepresentation of historical or mythological events in order to support false statements. A typical example of this category is the false claim that in various works of the Ancient Greek writers there are prophecies that foretell the coming of Jesus Christ.

Table 1.

Fake news types, cases & percentages.

The scope of this study is to reveal the characteristics of fake news in the Greek public sphere, and the extent to which it penetrates news outlets. In more detail, the data categories recorded are the following: postdate, non-true story type, news website link, fact check confirmation link, website name, page type (portal, newspaper, tv, facebook), traffic position, on the official Alexa.com (Alexa 2019) website. Alexa.com top 500 is a measure reference of a site’s online and global traffic and popularity. We have to mention here that the Alexa top 500 list of the most visited websites in Greece has been used in order to categorize non-true stories cases according to the popularity of the medium where a non-true story is found. A sample of the way and method all the above referred data were categorized and analyzed is displayed in the following figure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data entry process sample.

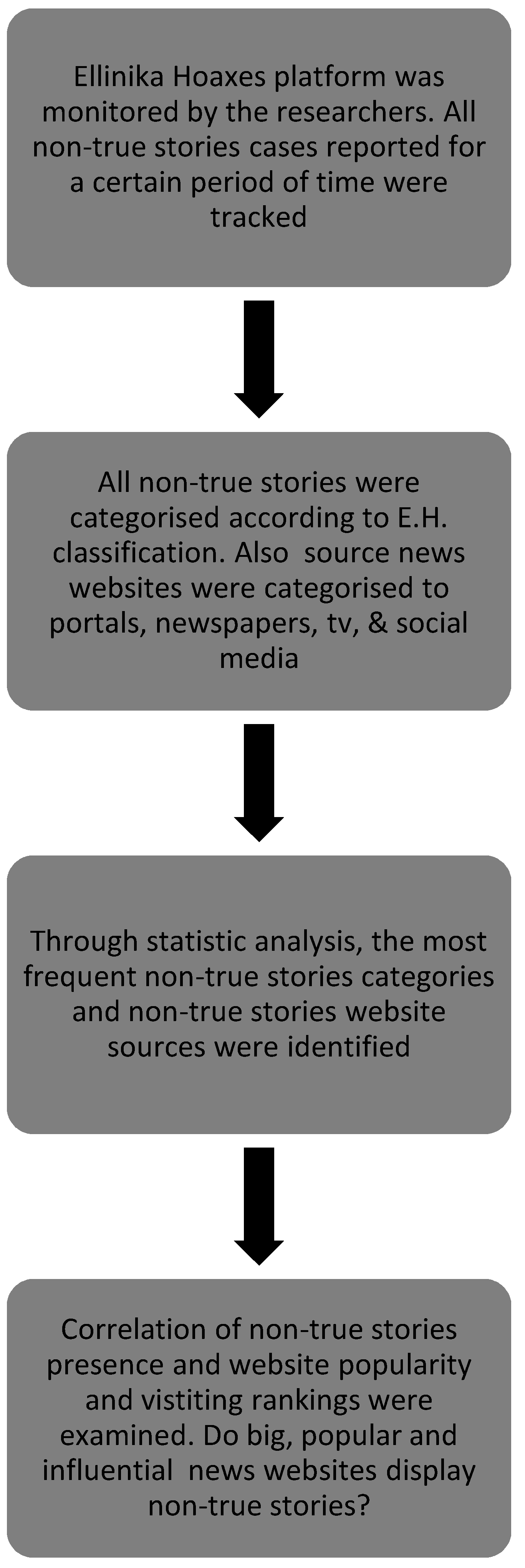

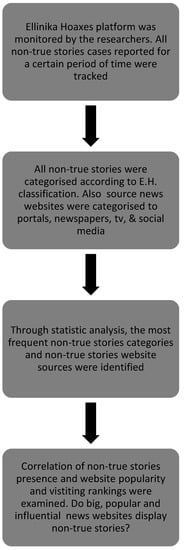

The research procedure follows-up the findings of Lamprou and Antonopoulos (2020) in order to expand the research potential of non-true stories diffusion in the Greek public sphere and reveal more characteristics of the Greek mediascape on the issue of non-true stories. There is a significant gap in research on non-true stories (fake news, misinformation, and other types in Greece). The main steps and phases of the research methodology procedure are generally described in the following scheme (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

The summary of the methodology.

As mentioned above, few research attempts have been conducted in Greece on non-true stories and fact-checking platforms.

Based on the intention to map the characteristics of non-true stories in the Greek mediascape, and on the attempt to highlight whether a crowdsourcing-based fact-checking platform can successfully contribute in revealing non-true stories with different origin and quality characteristics, this paper shapes its research orientation with the following research questions and a research hypothesis:

RQ1: How many stories cases will be classified as fake and be refuted during the time period of this research?

RQ2: In which categories of news websites do non-true stories appear most often?

RQ3: Which category of non-true stories is most common?

RQ4: Are fake news more present on high or low traffic sites? How safe and “clean” are the big popular news websites?

RH1 (hypothesis): What percentage of the fake news appears in the “upper layers” of the most popular Greek sites? It is assumed that fake news will be found mostly on “marginal” low traffic news websites.

The research recording procedure (walkthrough method) commenced on October 1 and ended on 31 December 2019.The following analysis yielded a number of N = −521cases of non-true stories of all categories. More analytically in the category of “hoaxes” 201 cases were detected, in the category of misinformation137, in fake news 94 cases, in “pseudoscience” 24, in the mix of events and falsifications but also in myths and history 15 cases, in conspiracy theories 12, and finally 10 cases belonged to no category, according to the Facebook approved fact-checking website “Ellinika Hoaxes” (Table 1).

The analysis also yielded interesting data concerning non-true and the news outlets that publish them. From the total of N = 521 cases of busted non-true stories 41% were detected in the 500 most popular sites in Greece according to Alexa.com rankings (Table 2). We have to mention here, that the Alexa top 500 most visited sites in Greece ranking list includes not only news websites but websites of any kinds and categories. This is a fact that makes more important the findings of this dissertation because the popularity rankings mentioned derive from general top-visited sites rankings (including bank websites, state organizations websites and other), and not only news media websites.

Table 2.

Cases detected in Alexa top 500 rankings in Greece.

The categories of news websites that spread fake news according to the Facebook approved fact-checking platform Ellinika Hoaxes have vast differences (Table 3) More specifically from the total number of cases N = 521, portals and blogs yielded 414 cases, a percentage of 78%. Newspapers websites, TV websites, and Facebook pages yielded 34 cases (6%), 12 cases (2%), and 40 cases (8%), respectively.

Table 3.

Cases detected per website category.

The statistical analysis of the data continued in order the dissertation to focus to the most popular websites, those that have the most significant impact on the public sphere of Greece and therefore affect more people and social groups.

Our new sample now is only those cases refuted by “Ellinika Hoaxes” fact-checking platform which were detected to the Alexa top 500 most popular websites in Greece N = 217. On this new narrower sample researchers aim to highlight what happens to the upper level of the most popular news websites in Greece considering that popularity makes them more influential and gives them greater share of advertising revenue. Thus, researchers as displayed in Table 4, decided to focus on different progressive layers of news websites in Greece in terms of popularity according to the Alexa top 500 most visited websites in Greece. More specifically, four layers of popularity were formed for the needs of the research. Group D < 250 where the news websites examined were ranked in popularity positions up to 250, Group C < 100 where the news websites examined were ranked to popularity positions up to 100, Group B, where the news websites examined were ranked to popularity positions up to 50 and finally Group A < 25, where the fake news examined, were ranked to popularity positions up to 25.

Table 4.

Non-true stories cases detected/layers of popularity.

The results of the statistical analysis were: Group D: 166 cases (76%) of refuted non-true stories, Group C: 130 cases (60%), Group B: 118 (54%) and Group A: 89 cases (41%). The percentage refers to the sample of the 217 cases that were detected in Alexa top 500 most visited news websites in Greece.

3.2. Qualitative Part of the Study

In order to confirm, expand, strengthen and reinforce the findings and conclusions of this dissertation’s quantitative research, researchers conducted also qualitative research. Data collection in qualitative research involves a variety of techniques: in-depth interviewing, document analysis, and unstructured observations (Jensen and Jankowski 2002). When you want to gather rich data, in order to confirm your research results, in-depth interviews can be a valuable tool to guide your work. There really is no substitute for face-to-face communication, and in-depth interviews provide the structure to ensure that these conversations are both well-organized and well-suited to your purpose (Guion et al. 2011). In-depth interviews are one of the most efficient methods of collecting primary data. Unlike a simple questionnaire or rating scale, in-depth interview is conducted with an intention of uncovering in-depth details of interviewee’s experience and perspective on a subject. Being more effective and less structured, one of the most important benefits of in-depth interview is that it helps to uncover more detailed and in-depth information than other data collection methods like surveys (Showkat and Parveen 2017).

The in-depth interview method was selected, and three media experts were interviewed in real-time with the use of zoom software. The first stage of organizing the procedure was thematizing. In this stage, it is important to clarify the purpose of the interviews. The main purpose of the interviews was clearly the triangulation of the results and conclusions exported from the quantitative research. In simple words, researchers scoped to confirm whether the research questions and hypotheses of the quantitative research part are accurate or not. According to Guion et al. (2011) once you have decided on your general-purpose, then you can pinpoint the key information you want to gather through the in-depth interview process. Three media experts of different origins and professions with deep knowledge of the Greek and international mediascape and media system were selected in order to be interviewed. The first in-depth interview was addressed to Christos Panagopoulos, a professional journalist and editor in chief in CNN Greece media outlet. The second in depth-interview was addressed to Dr. Theodora Maniou a professional Journalist and Mass Media lecturer at the University of Cyprus. The third interview was addressed to Dr. Anastasia Katsaounidou, a professional fact-checker in the “Ellinika Hoaxes” fact-checking platform. Interviewees were contacted via email whether they wish to participate in scientific research on non-true stories and fact-checking through face-to-face in-depth interviews using the zoom software. All of them responded positively.

The step followed was the planning of the interview. In this step, the main research questions, results, and conclusions of the quantitative research that preceded were adapted and expanded to the following interview questions:

- Q1.

- Do you consider that there are cases of non-true stories in the Greek public sphere and to what extent? In which categories of news websites do you mainly find fake news?

- Q2.

- Are the major popular news sites “clean” and safe from fake news?

- Q3.

- What is your opinion on Fact-Checking?

- Q4.

- Can the public (crowd) contribute to the fight against fake news? Do you think that a crowdsourcing model (public participation) can help?

- Q5.

- What else do you think could be done to tackle the phenomenon of fake news?

The research method of in-depth interviewing is used to learn of individual perspectives of one or a few narrowly defined themes. The questions used to guide the interview are often semi-structured, that is the researcher has formulated a set of questions that all interviewees will be asked. Then, depending on the interviewee’s answers, each in-depth interview will take different twists and turns and follow its own winding path—an important component being to have the freedom to follow up on related themes raised by the interviewees themselves. After following such new paths, the researcher then returns to the prepared set of core questions (Brounéus 2011). Researchers decided to use the semi-structured interview format in order to give the interviewees enough space to unroll their answers.

In some cases, questions were expressed in different ways in order to confirm that the answers were accurate and real and furthermore to make conversations more human and straightforward.

3.2.1. Conducting of the Interviews

Interviews with the experts were conducted in real time, in the Greek language, face to face using the zoom software as mentioned above. Interview one (Int1) was addressed to Mr. Christos Panagopoulos professional journalist and editor in chief in CNN Greece. The interview was conducted on Monday 14 June 2021. The next interview (Int2) was addressed to Dr. Theodora Maniou, a professional Journalist and Mass Media lecturer at the University of Cyprus. The interview was conducted on Tuesday 15 June 2021. The third interview (Int3) was addressed to Dr. Anastasia Katsaounidou, a professional fact-checker in “Ellinika Hoaxes” fact checking platform. The interview was conducted on Wednesday 16 June 2021. All interviews were conducted by Evangelos Lamprou according to plan and the planned questions were asked to interviewees in a semi-structured way. All questions and answers were recorded via the zoom software recording feature. After the interviews were completed and recorded, the next step was transcribing. Transcribing involves creating a verbatim text of each interview by writing out each question and response using the audio recording. Three different transcriptions were created, one for each interview and translated from Greek to English.

The next step was analyzing the answers the interviewees gave in the transcripts. Analyzing involves re-reading the interview transcripts to identify themes emerging from the respondents’ answers. Researchers can use their topics and questions to organize their analysis, in essence synthesizing the answers to the questions proposed. The final step was verifying and triangulation. Verifying involves checking the credibility of the information gathered and a method called triangulation is commonly used to achieve this purpose. Triangulation involves using multiple perspectives to interpret a single set of information.

3.2.2. Answers

In this stage, after rereading and thorough analysis of the transcripts the relevant answers of the three interviewees were organized according to each question. Interview 1, (Int1) was addressed to Christos Panagopoulos. Interview 2, (Int2) was addressed to Theodora Maniou. Finally, Interview 3 (Int3) was addressed to Anastasia Katsaounidou. Researchers pinpointed the relevant content of each interview’s answer to the relevant questions. Through the interviews the appropriate answers for each question were selected. The answer of each participant was compared to the answers of two others in order for triangulation to be achieved.

Q1. Do you consider that there are cases of non-true stories in the Greek public sphere and to what extent? In which categories of news websites do you mainly find fake news?

Int1:

Interviewee 1 states that there definitely are non-true stories in the Greek public sphere in most categories of Greek news websites. The frequency of appearance though is another matter. Furthermore, he states that there are a lot of “non-serious” news websites or blogs that publish “masked lies” and present them as news, blending them with some touch of truth for the sake of clickbait. Some of these news websites might be extremely popular. Popularity itself in many cases does not guarantee necessarily the quality or absence of fake news.

Int2:

Interviewee 2 agrees that non-true stories appear on all kinds of news websites, because the term “non-true stories”, has many meanings: It includes misinformation and disinformation. It is a different thing to publish non-true stories intentionally in favor of deceiving or clickbait and different to publish non-true stories due to lack of or poor cross-checking. It is a phenomenon that occurs everywhere to a greater or lesser degree, with a tendency for the phenomenon to reduce as we move towards legacy media. There is definitely much lesser possibility to encounter non-true stories in legacy media. Though, it is not impossible.

Int3:

Interviewee 3 also agrees that non-true stories could not be absent from the Greek public sphere. It is possible to encounter them in most news media websites categories. As far as traditional journalism is concerned there are not that many cases of non-true stories. However, there are many cases where they can be mainly found on specific websites and blogs that use the clickbait strategy, or specific news media websites and papers such as “Makeleio” that have a scrappy fan base based on conspiracy theories and rumors which most of the time are proven false. Special mention has been made to the Greek sports radio stations and their websites where “lots of peculiar non-true stories” can be found.

Q2. Are the major popular news sites “clean” and safe from fake news?

Int1:

Interviewee 1 states that major popular news websites are definitely not clean from non-true stories. Though, the frequency of appearance is substantially lower. He also makes clear that popularity does not always go hand in hand with professional media. The main reasons major professional news websites fall in the pit of non-true stories are lack of time and sometimes lack of personnel. Many times, the pressure from competition the vast volume and the speed of incoming information makes journalists in news media websites not properly cross-check the validity of their content. Furthermore, due to the media crisis, many media outlets are understaffed with few journalists available to do the cross-checking. What is most important is that it is cleared up that most of the time the non-true stories donot come out intentionally from major popular websites.

Int2:

Interviewee 2 states that the phenomenon of non-true stories happens everywhere to a greater or lesser degree, of course with a tendency to reduce the phenomenon as we move towards legacy media. She insists that the discrimination between misinformation and disinformation is crucial. She agrees that the percentage of non-true stories found usually in legacy media is much lower than in the “non-serious” news websites. Her answer coincides with the answer given to Q1.

Int3:

Interviewee 3 states that no news organization is completely clean from false news and this is something to be expected. Nevertheless, there is no non-true story pattern in legacy media. Non-true stories may be published but this is rather an accident or poor journalism and poor reportage and not an intended pattern that is followed. She insists that even large news websites such as “Proto Thema” may sometimes present non-true stories but that does not mean that the medium follows this practice.

Q3. What is your opinion on Fact-Checking?

Int1

Interviewee 1 states that fact-checking is primarily a journalist’s job, though sometimes journalists neglect this important feature and obligation. According to him fact-checking is something extremely important and several models could be functional. Nevertheless, he insists on the internal fact-checking bureaus model which is followed by several large media in different countries such as the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, one of Germany’s largest newspapers with a fact-checking section of over 200 people. Interviewee 1 also admits that fact-checkers cannot only be people who necessarily belong to the same field, they can be researchers, independent researchers who are collaborating with the medium, and this might be a non-positive evolution for his profession.

Int2:

Interviewee 2 states that fact-checking is not a new concept or a new idea; what is new is the way fact-checking is done now. Due to technological advancements sometimes journalists, especially the most senior ones, do not always catch up with technology and cannot always cope with demanding bits of incoming information which need to be cross-checked. This is the reason why in most journalism departments in the university journalism schools internationally there are courses which arm the hand of the journalism students, in order to be capable of performing fact-checking procedures using advanced technological tools. Though, fact-checking can be used in various models.

Int3:

Interviewee 3 states that fact-checking is not news as we use to know it. People who want to get informed or read the news do not visit a fact-checking platform as their first choice. According to her, fact-checking maybe somehow a distant relative of journalism but it is in a way a completely separate scientific field that should be practiced independently in order to control the spread of non-true stories in the public sphere. Fact-checkers are also called “verification specialists” and not as fact-checker journalists. She claims that fact-checkers, although they use the same tools as journalists, are in a totally different field that supplements journalism.

Q4. Can the public (crowd) contribute to the fight against fake news? Do you think that a crowdsourcing model (public participation) can help?

Int1:

Interviewee 1 states that the crowd can definitely contribute to the fight against non-true stories, through social media or using the communication or comment forms of the news website. A journalist can have immediate communication with his readers and unlike the old linear Lasswell communication model feedback is not that time-consuming. Communication and commenting can be done immediately, and many times can literally save the prestige of the journalists who write the news, whether it is for a news media website or some other platform. Nevertheless, he states that the journalist or at least an expert must be the one to have the general command and be in charge of a procedure like that.

Int2:

Interviewee 2 states that crowdsourcing could definitely contribute to the fight against non-true stories but suggests that a model based solely on crowdsourcing would not work. She suggests that the public will have to work hard to do this. Audiences are used to receiving information in an easy way and the average user would not easily devote time to a demanding and complex procedure. The solution proposed is a combination model where experts and trained professionals will collaborate with the crowd in order to detect potential cases of non-true stories, cross-check them, and refute them if necessary.

Int3:

Interviewee 3 states that the public indeed can contribute to the fight against non–true stories. She proposes the crowdsourcing model used by “Ellinika Hoaxes” where the crowd informs the fact-checkers about cases of potential non-true stories or even can assist in the procedure of refuting non-true stories. She suggests that experts cannot take a random article that has no notification, has no impact, and apply fact-checking given the limited resources of the fact-checking platform. She also states that this procedure helps the public which is trained throughout the process. Readers are trained for example that it is not appropriate to share and upload the actual pages that potentially display fake news which must be cross-checked and refuted but to use the archived versions of the pages and not click on their pages in order to avoid clicking on websites that constantly reproduce and publish fake news. She concludes that in “Ellinika Hoaxes” fact-checking platform the crowdsourcing model combined with fact-checking professional experts actually applies.

Q5. What else do you think could be done to tackle the phenomenon of fake news?

Int1:

Interviewee 1 suggests that apart from the independent bodies a very useful strategy and a new trend in fact-checking models is that digital publishers are now beginning to realize that it is necessary to create what the journalists call an editorial room within the editorial office. This internal core in the editorial room is nothing more than a fact-checking desk. This means in simple words that each media corporation separately should start integrating, create its own separate fact-checking infrastructure within the existing structure of the media. This thing can be, for example, the fact-checking office of an entire media group corporation. In that way, journalists and media retain their gate-keeping role and limit the minimum potential cases of non-true stories.

Int2:

Interviewee 2 suggests that we cannot predict fake news or the evolution of technology in media or other fields always accurately. This means that we cannot predict non-true stories and the ways they will occur in the future. She claims that one of the most important things we can do is educating the public on media, their functions and non-true stories of all kinds, their purpose, and origin. Media literacy might be a very important element in the fight against non-true stories.

Int3:

Interviewee 3 suggests that an important factor in fighting non-true stories in the public sphere is how the refutation of non-true stories is disseminated to the public. Many times, the impression of reality for a non-true story remains in the public’s collective perception. In simple words, it is not enough for non-true stories to be refuted but it is also extremely important that this refutation has to be communicated properly in the public sphere. According to her, non-true stories are much more likely to be permanently imprinted on a person’s brain than the truth. There are many reasons why this happens. Thus, finding, cross-checking, and refuting non-true stories is not enough. Of equal importance is the public to know that a story which is not true has been refuted, and that story has to be published in its right dimensions.

4. Analysis & Discussion

Non-true stories and fake news are clearly present in Greek news websites and in the Greek public sphere. Over a period of three months, (October to December 2019) the Facebook-approved fact-checking platform “Ellinika Hoaxes” refuted 521 cases of all kinds, a quite impressive number of non-true stories diffused in the Greek public sphere (RQ1).The origin of the non-true stories is quite interesting; most of them come from portal sites and blogs (78%) while newspaper websites, and TV stations news websites seem to retain their credibility with much fewer percentages of fake news (RQ2), implying that professionalism in journalism and credibility go hand by hand. This finding is also strongly supported by the findings of the qualitative research part of this dissertation. Legacy media and news websites of traditional media and newspapers seem to retain their credibility compared to portals and blogs (Q1). All interviewees believe that indeed non-true stories do exist everywhere, but the phenomenon is limited when it comes for legacy traditional media.

Hoaxes, misinformation, and fake news are the three most frequent kinds of non-true stories busted by “Ellinika Hoaxes” according to the fact-checking platform’s categorization.

Misinformation and fake news hold a very high rate, 26%, and 18%, respectively, a fact which might imply that criminally deceiving on purpose the public is the primary aim of a substantial number of non-true stories. Hoaxes also keep a high percentage (38%) indicating that media outlets in Greece have been contaminated with non-true stories at a significant scale (RQ3).

A crucial characteristic of non-true stories is their popularity and reach, and as a consequence the extent they affect and contaminate the public sphere and society. In our research, almost half (41%) of the cases busted by “Ellinika Hoaxes” belong to the top 500 most visited websites (all kinds of websites) in Greece. That implies that fake news and misinformation are not something rare and marginal but something that affects people, their judgment, ideas, beliefs, and attitudes (RQ4).

Research Hypothesis 1 (RH1) seems not to be confirmed. We assume that the big popular news websites due to their large audience and their high advertising revenues concerning big companies and big audiences will have a moderate affection for fake news and misinformation. Unfortunately, the results are quite disappointing. Top 50 and top 25 most popular layers of news websites in Greece display 89 and 118 cases of non-true stories, respectively. As mentioned above, fake news is not a problem only for low quality, low traffic, low revenue, and marginally popular news websites but a kind of cancer that contaminates every category and every media outlet—even the most respectful and popular. The findings of RQ4 and RH1 are partly supported by the qualitative part of this dissertation’s research where although participants claim (Q1, Q2) that major legacy media and large news websites publish limited cases of non-true stories—they cannot deny in any case the existence of non-true stories even in the most legit and popular news websites. Furthermore, legacy media and popularity do not always coincide. Thus, the non-true stories cases penetrating big, popular, and legacy news websites derive from the time pressure most journalists working in digital media feel and from the lack of cross-checking, which seems difficult for many web journalists working under time pressure (Q2).

Fake news is a menace for society and the public sphere. What makes us more skeptical is that “Ellinika Hoaxes”, although it seems to be a successful endeavor, admits that the platform cannot detect all fake news on the Greek internet. This claim clearly implies that the number of fake news circulating might be even larger. Nevertheless, there is a positive side. Fact-checking seems to be a promising communication model but not all stakeholders of the media industry agree on the way it has to be utilized. Especially professional journalists, although they find it to be a positive perspective, might feel threatened from the possibility that someone else may take over some of their responsibilities in the near future (Q3).

What also seems promising is the implementation of crowdsourcing strategies in fact-checking procedures. In the qualitative part of this dissertation’s research interviewees admitted the merits of crowdsourcing and the public’s participation and proposed that the public can help through different crowdsourcing techniques in refuting non-true stories cases, but not alone. What is mainly proposed is a combined model where crowdsourcing strategies ally with professional fact-checkers (Q4).

Public opinion seems vulnerable to misinformation and all kinds of fake news in general, but it might be able to defend itself through crowdsourcing strategies where crowd voting, crowd creation, and crowd wisdom help fact-checkers detect and bust fake news early before their circulation becomes harmful for society with irreversible consequences. It looks like a “call the watchdog”, situation but it seems that in our case it is working satisfactorily as an emerging model. In an era where journalists are similar to entertainers and seem unable or unwilling to play their fundamental role as gatekeepers of democracy, fact-checkers in combination with the public and fundamental crowdsourcing strategies might be the answer to all kinds of misinformation and a model that has to be funded and supported by all stakeholders concerned. Furthermore, the qualitative part of this dissertation’s research yielded useful proposals from the participants on what can be done for stopping non-true story circulation (Q5). Int1 proposed that journalists should retake over fact-checking in internal bureaus’ inside media. Int2 proposed that the public should be more trained to recognize non-true stories. Int3 stated that verified information and refuted non-true stories have to be diffused more widely in the public sphere in order for the public not to retain the initial fake information in mind.

5. Conclusions

In one way or another, media environments around the world are changing. The change is not only a change in content but also a change in the ways in which citizens discover, use, consume, and interact with content. These new conditions have significant implications for what the media report, the way in which the content is consumed, and, finally, the quality of informed citizenship (Mattelart et al. 2019).

Beyond any doubt non-true stories also exist in the Greek mediascape, leading citizens to wrong decisions, misleading them for important decisions for their everyday lives, and even creating misunderstanding among different social teams and stakeholders. What is clear with the findings of this research is that non-true stories, fake news, and misinformation penetrate many different media outlets, even legacy and historic media. Brand qualities such as the trustworthiness of traditional media outlets might be under question. This mainly happens (Q3) because of the time pressure to editors and journalists, which leads them lots of times not to cross-check their material. Though legacy media really seems not to publish non-true stories intentionally, compared to other outlets, there is no absolute guarantee that they are completely clear from non-true stories, as the quantitative and qualitative triangulation of this dissertation’s research indicates. What is also obvious is that the popularity of content providers does not always guarantee the quality or the accuracy of the information provided. It has also to be understood that popularity and legacy of the media outlets do not always coincide. Social media provides the ability for fake news to spread fast and have made the situation even more complicated. Fact-checking platforms such as “Ellinika Hoaxes” seem like a fair and promising solution to tackle the fake news phenomenon, proving in action their effectiveness, as displayed in this dissertation both in the quantitative and the qualitative sections of the research. Technological giants such as Facebook have already commenced collaborations with such platforms in order to upscale the content delivered to users trying to restrain fake news sharing. Experts believe that fact-checking is a rising model for restraining non-true stories, but they do not seem to agree on the forms and methods of its implementation. Journalists might seem apprehensive due to eminent loss of responsibilities for their profession and want to retain the fact-checking procedure in their media. On the other hand, fact-checkers believe that news verification is a completely new field that has to be expanded independently (Q3). In conclusion, it is crucial for societies and democracy citizens to participate in the fact-checking procedure and not leave this critical task to companies, corporations, and specialists. Crowdsourcing in any of its types, (crowdwisdom, crowdcreation, crowdvoting, and crowdcreation) can provide to citizens the opportunity to participate in the fact-checking game and shape the public sphere in favor of the public interest. Though the participation of the public and crowdsourcing strategies are considered by all as useful and necessary, it is admitted that only a combined model, which utilizes crowdsourcing strategies and professional fact-checkers and experts, can be viable and effective.

“Ellinika Hoaxes” platform uses crowdsourcing strategies in combination with professional fact-checking personnel, which seems to give effectiveness to the platform’s performance.

Another important conclusion of this study is the innovative classification of the Greek fact-checking platform of non-true stories in categories. Classifying non-true stories in categories such as Misinformation, Pseudoscience, Scams, Fake News, and Hoaxes, Mixing of Facts and Falsifications, Conspiracy Theories, Myths & History makes the concept of non-true stories easier to study and ultimately eliminate. We have to mention that Ellinika Hoaxes’ classification of non-true stories derives not from literature, scientific research, or theory but mostly from everyday experience in encountering non-true stories in Greek mediascape and their practical distinction. Often, certain non-true stories are categorized in more than one category, but in general, the different categories help fact-checkers to find them, track them, and ultimately shoot them down. Maybe fact-checkers following different communication and fact-checking models should agree on a definite protocol of non-true stories classification, which is all until now covered under the umbrella term “Fake News”. A definite protocol could lead to comparable data from all over the world and could establish a new branch in communication theories and communication models. Fact-checkers, communication scholars, and journalists from all over the world should agree on a practical non-true stories classification protocol in order to compare, access, analyze, and fight non-true stories.

Concluding a new journalistic communication model this of crowd sourced fact-checking platform is on the rise. Fact-checkers supported by the crowd seem to be effective. New collaborations and more improved platforms which enhance the vast power and knowledge of the citizens in collaboration with skilled fact-checkers might be the answer to fake news and misinformation in modern societies.

6. Limitations

Limitations for the current research are that the non-true stories cases and data were found only from the “Ellinika Hoaxes” fact-checking platform only for Greece.

More detailed research with more characteristics of non-true news stories concerning more cases and strategies and more expert interviews may be conducted in the future. Crowd-sourced fact-checking platforms shape a new emerging communication model on fake news verification. New platforms enhancing more strategic advantages of crowdsourcing methods could also be introduced in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.L.; methodology, E.L.; software, E.L., N.A., I.A. and C.A.; validation, E.L.; formal analysis, E.L.; investigation, E.L., N.A., I.A. and C.A.; resources, E.L.; data curation, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.L. and N.A.; writing—review and editing, E.L. and N.A.; visualization, E.L.; supervision, N.A.; project administration, N.A. and E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All fact-checking articles with cases of non-true stories that have been used are publicly accessible on the website https://www.ellinikahoaxes.gr (accessed on 27 April 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References