An Examination of the Interaction of Democratic Ideals with Journalism Training Programmes in the Global South: The Case of Cambodia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Cambodia and Journalism Training

3. Cultural Variations of Journalism Ideals

4. Democracy and Journalism

5. Journalism Training in the Developing World

6. Methodological Approach and Overview of Data

7. Finding and Emergent Themes

7.1. Programme Facilitators’ Perceptions of Journalism Functions

7.2. Normative Conceptualisations of Working Journalists

7.3. Theme A. ‘Developing Democracy’ Seen as a Key Journalism Function

“They all felt free and fair and open media would help to bring about the democratic process. In some countries it’s been more apparent than others.”—DR

“The job [of the press] is to bring society to a point where the democracy level will change.”—TI

“I think it is very important [for journalism] to bring democracy. If [Cambodians] don’t know about [democracy] it is easier to boss them.”—JL

7.4. Theme B. ‘Affect Change’ Function Features More Strongly among Journalists Than Facilitators

“You don’t just wait and see what happens and write about the public reaction. Sometimes you have to play a role to find something that will help the society.”—JL

“I can change my country by becoming a journalist in a way that I cannot by being a teacher.”—JL

“In the future journalists have to know, not only how to write articles, they have to be themselves like a doctor … cure the problem.”—JL

7.5. Theme C. Journalism Seen as Having an Explicitly Political Function

“Before you jump into politics, you (do) journalism first.”—TL

“[Journalists] give information to people so people can make their value judgement.”—TL

“We must educate the audience, explain to them and make them understand.”—JL

7.6. Theme D. Divergence over the Importance of Neutrality, Objectivity and Independence

“[we teach them] not to take sides politically. The newsroom is a non-political area, even though some people have strong views.”—TI

“I think [journalists] can take on board and understand the need for … objectivity and all of that. It is common sense.”—TI

“I don’t want to write a story to support the government because such a story would be the opposite of my opinion.”—JL

7.7. Theme E. Basic Skills/Vocational Approach to Training Emphasised over a More Educational Approach

“I thought—what kind of training did they get? What can you learn in three days, frankly, that can be any good?”—DR

“[In college] you only learned the theory. We did not know the practice. The job teaches”—JL

8. Analysis and Discussion of Data

9. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, Christopher W. 2014. The sociology of the professions and the problem of journalism education. Radical Teacher 99: 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Appadurai, A. 1996. Modernity al Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minnesota: U of Minnesota Press, Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Aumente, Jerome, Peter Gross, Ray Hiebert, Owen Johnson, and Dean Mills. 1999. Eastern European Journalism: Before, During and After Communism. New York: Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Banda, Fackson. 2007. An appraisal of the applicability of development journalism in the context of public service broadcasting (PSB). Communication 33: 154–70. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, Carlos. 2012. Transatlantic Views on Journalism Education Before and after World War II: Two Separate worlds? Journalism Studies 13: 534–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiser, Elana. 2018. Hundreds of journalists jailed globally becomes the new normal. Committee to Protect Journalists. Available online: https://cpj.org/reports/2018/12/journalists-jailed-imprisoned-turkey-china-egypt-saudi-arabia/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Bennett, W. Lance. 1998. The media and democratic development: The social basis of political communication. Communicating Democracy: The Media and Political Transitions, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Guy. 2000. Grave new world? Democratic journalism enters the global twenty-first century. Journalism Studies 1: 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernacki, Patrick, and Dan Waldorf. 1981. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociological Methods & Research 10: 141–63. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, Cecil. 1997. Democratisation: The dominant imperative for national communication policies in Africa in the 21st Century. Gazette 59: 253–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bumille, E. 2012. In Cambodia, Panetta Reaffirms Ties with Authoritarian Government. New York Times, November 16. [Google Scholar]

- Cammaerts, Bart, Brooks DeCillia, and João Carlos Magalhães. 2017. Journalistic transgressions in the representation of Jeremy Corbyn: From watchdog to attackdog. Journalism 21: 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carey, James W. 2000. Some Personal Notes on US Journalism Education. Journalism, Theory, Practice and Criticism 11: 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christians, Clifford G. 2009. Normative Theories of the Media. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Judith. 1995. Phoenix from the ashes: The influence of the past on Cambodia’s resurgent free media. Gazette 55: 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortadi, J., P. Weiss Fagan, and M.A. Garreton. 1992. Fear at the Edge: State Terror and Resistance in Latin America. Berkley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Datta–Ray, Sunanda K. 2006. Asia must evolve its own journalistic idiom. Issues and Challenges in Asian Journalism, 44–64. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N. 1997. Interpretive Ethnography: Critical Pedagogy and the Politics of Culture. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Deuze, Mark. 2005. What Is Journalism? Professional Identity and Ideology of Journalists Reconsidered. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake, W. 1988. The Need for Asian Approaches to Communication. Edited by Dissanayake, W. Communication Theory: The Asian perspective. Singapore: Asian Mass Communication Research and Information Center, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue, George A., Phillip J. Tichenor, and Clarice N. Olien. 1995. A Guard Dog Perspective on the Role of Media. Journal of Communication 45: 115–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, Bevelyn. 2016. Rethinking journalism education in African journalism institutions: Perspectives of Southern African journalism scholars on the Africanisation of journalism curricula. AFFRIKA Journal of Politics, Economics and Society 6: 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein, Harry. 1998. Congruence Theory Explained. In Can Democracy Take Root in Post-Soviet Russia? Explorations in State-Society Relations. Edited by Reisinger William. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Edeani, David O. 1993. Role of development journalism in Nigeria’s development. Gazette 52: 123–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Issawi, Fatima, and Bart Cammaerts. 2016. Shifting journalistic roles in democratic transitions: Lessons from Egypt. Journalism 17: 549–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Entman, Robert M. 2010. Media framing biases and political power: Explaining slant in news of Campaign 2008. Journalism 11: 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, Michael. 2006. Promoting values—As West meets East. International Journal of Communication Ethics 3: 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, Michael. 2010. The Press and Democracy Building: Journalism Education and Training in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe during Transition. Master’s dissertation, Technological University Dublin, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- Freedom House. 2020. Annual Report. Available online: https://freedomhouse.org/country/cambodia (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Gardeström, Elin. 2017. Losing Control: The emergence of journalism education as an interplay of forces. Journalism Studies 18: 511–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, Robert A. 2017. Democracy, climate crisis and journalism: Normative touchstones. In Journalism and Climate Crisis. London: Routledge, pp. 20–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hallin, Daniel C., and Paolo Mancini. 2004. Comparing Media Systems: Three Models of Media and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, Basyouni Ibrahim. 2016. Towards a global journalism ethics model: An Islamic perspective. The Journal of International Communication 22: 188–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanitzsch, Thomas, and Tim P. Vos. 2018. Journalism beyond democracy: A new look into journalistic roles in political and everyday life. Journalism 19: 146–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanitzsch, T., F. Hanusch, C. Mellado, M. Anikina, R. Berganza, I. Cangoz, M. Coman, B. Hamada, M. Elena Hernández, C.D. Karadjov, and et al. 2011. Mapping journalism cultures across nations: A comparative study of 18 countries. Journalism Studies 12: 273–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harvey, D. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, E., and R. McChesney. 1997. The Global Media: The New Missionaries of Corporate Capitalism. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Hoepfl, Marie C. 1997. Choosing qualitative research: A primer for technology education researchers. Journal of Technology Education 9: 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jallov, Birgitte. 2005. Journalism as a Tool for the Formation of a Free, Informed and Participatory Democratic Development. In Swedish Support to a Palestinian Journalist Training Project on the West Bank and Gaza for the Period 1996–2005. Stockholm: SIDA. [Google Scholar]

- Josephi, Beate. 2005. Journalism in the global age: Between normative and empirical. Gazette 67: 575–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephi, Beate Ursula. 2010. Journalism Education in Countries with Limited Media Freedom. New York: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Josephi, Beate. 2013. How much democracy does journalism need? Journalism 14: 474–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephi, Beate. 2017. Journalists for a Young Democracy. Journalism Studies 18: 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyango, Yusuf, Jr., Folker Hanusch, Jyotika Ramaprasad, Terje Skjerdal, Mohd Safar Hasim, Nurhaya Muchtar, Mohammad Sahid Ullah, Levi Zeleza Manda, and Sarah Bomkapre Kamara. 2017. Journalists’ development journalism role perceptions: Select countries in Southeast Asia, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. Journalism Studies 18: 576–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, K. 2018. Cambodia ‘Fake News’ Crackdown Prompts Fears over Press Freedom. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/06/cambodia-fake-news-crackdown-prompts-fears-over-press-freedom (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Lo, V.H., J.M. Chan, and Z. Pan. 2005. Ethical attitudes and perceived practice: A comparative study of journalists in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan. Asian Journal of Communication 15: 154–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo–Ocando, Jairo. 2018. A mouthpiece for truth: Foreign aid for media development and the making of journalism in the global south. Brazilian Journalism Research 14: 412–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahler, Anne Garland. 2018. From the Tricontinental to the Global South: Race, Radicalism, and Transnational Solidarity. Duke: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, Julian, and Kelechi Onyemaobi. 2020. Precarious Professionalism: Journalism and the Fragility of Professional Practice in the Global South. Journalism Studies 21: 1836–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, Brian. 2009. Journalism in the 21st century—Evolution, not extinction. Journalism 10: 347–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, C. 2016. Universals without absolutes: A theory of media ethics. Journal of Media Ethics 31: 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, C.S.H.N. 2010. Education in Mass Communication—Challenges and Strategies: A Case Study of Indian Scenario. The Romanian Journal of Journalism & Communication 1: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis. 2017. The one thing journalism just might do for democracy: Counterfactual idealism, liberal optimism, democratic realism. Journalism Studies 18: 1251–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okigbo, Charles. 1985. Media use by foreign students. Journalism Quarterly 62: 901–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsaki, Evangelia. 2007. Decolonising journalism curricula: A research and ‘develop-ment’ perspective. Media Asia 34: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, Peter. 1994. Critical Studies, The Liberal Arts and Journalism Education. Journalism Educator 464: 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaisance, P.L., E.A. Skewes, and T. Hanitzsch. 2012. Ethical orientations of journalists around the globe: Implications from a cross-national survey. Communication Research 39: 641–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, Paola. 2017. Mapping citizen journalism and the promise of digital inclusion: A perspective from the Global South. Global Media and Communication 13: 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, L., and M. Pye. 1985. Asian Power and Politics. Cambridge: Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, Fergal. 2018. Failing to Prepare? Journalism Ethics Education in the Developing World: The Case of Cambodia. Journal of Media Ethics 33: 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, Shakuntala, and Herman Wasserman. 2007. Global media ethics revisited: A postcolonial critique. Global Media and Communication 3: 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reporters San Frontiers. 2019. Annual Report. Available online: https://rsf.org/en/cambodia (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Schudson, Michael. 1998. The Good Citizen. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schudson, Michael. 2002. The Sociology of News. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Soffer, Oren. 2009. The competing ideals of objectivity and dialogue in American journalism. Journalism 10: 473–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaselli, Keyan G. 2003. ‘Our Culture’ vs. ‘Foreign Culture’ An Essay on Ontological and Professional Issues in African Journalism. Gazette 65: 427–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, S. 2006. Social responsibility theory and the study of journalism ethics in Japan. Journal of Mass Media Ethics 21: 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2013. Teaching Journalism in Developing Countries and Emerging Democracies: The Case of UNESCO’s Model Curricula. UNESCO. Available online: bit.ly/1kYHRPX (accessed on 3 September 2018).

- United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). 1991. Media Guidelines for Cambodia, Drafted by the Information and Education Division of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia. Available online: http://www.aceproject.org/ero-en/topics/media-and-elections/mex08.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- US Agency for International Development (USAID). 1999. The Role of Media in Democracy, a Strategic Approach. Available online: http://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2496/200sbc.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Vasilendiuc, Natalia, and Rodica Melinda Sutu. 2020. Journalism Graduates Versus Media Employers’ Views on Profession and Skills. Findings from a Nine-Year Longitudinal Study. Journalism Practice, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, Stephen JA. 2008. Global Journalism Ethics: Widening the Conceptual Base. Global Media Journal 1: 137. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, H., and A.S. De Beer. 2004. Covering HIV/AIDS: Towards a heuristic comparison between communitarian and utilitarian ethics. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer, Jeffrey, and Susanne Wolf. 2005. Development Journalism out of Date? An Analysis of Its Significance in Journalism Education at African Universities. Munich: Munich Contributions to Communication. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Xiaoge. 2005. Demystifying Asian Values in Journalism. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The newspaper was shuttered by the Cambodian government in 2017. |

| 2 | Our usage of the term Global South’ here is primarily the conventional nation state definition (used by the World Bank and others) to describe low to middle income countries), but can also be broadly applied to what Mahler (2018) describes a more de-territorialised political economy definition of the term encompassing groupings of people and countries whose social agency is negatively impacted by globalisation. |

| 3 | It should be noted here that the vocational approach to journalism training in the west has evolved significantly in recent years towards a more education-oriented (longer-term, theoretical and institution-based) approach (Gardeström 2017). However, the historical dominance, as well as poor educational infrastructure and other practical obstacles, has meant that journalism programs in developing countries supported by Western aid have retained a vocational, practice-oriented and short-term, primarily aimed at building a broad level of basic capacity in the sector (Foley 2006). In Cambodia, as in other countries, this approach did evolve (further discussion on the more educationally oriented approach taken by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation from 2005 onwards is discussed later in this paper). However, the primary focus here is on the effect of that ‘early-stage’ approach to training (similar approaches to which are still being replicated elsewhere) and how this interacted with the understanding of the democratic norm. It must also be noted here that academically oriented approaches to journalism education are not without their problems, for example Vasilendiuc and Sutu’s (2020) highlighting of weaker adherence to professional values shown by student journalists who reiterated an academically induced picture of the profession. |

| 4 | The position of UNESCO in the historical debate on approaches to journalism training and media support in non-western environments is multi-faceted and more complex than this paper has the space to fully explore. To briefly summarise, UNESCO became a centre of activity for the New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO) debate during the 1970s and 80s, which critiqued what it identified as ‘Imperialistic’ tendencies inherent in approaches to encouraging media development in the non-western world. This critique and its proponents were sidelined to a degree by geopolitical manoeuvrings in the Cold War, but remains influential today in UNESCO and elsewhere. However, critics have claimed that any changes to the UNESCO approach at a local level have remained somewhat cosmetic, a critique which UNESCO itself acknowledges in its 2013 report on the adaptation of their model curricula. |

| 5 | While the more academically oriented approach taken by the Department of Media and Communication in the RUPP may impact on the Cambodian press sector in the future, too few graduates had emerged at the time of this study to significantly impact on the overall press culture. |

| 6 | Expert Commentators’ are defined as interviewees with a special degree of knowledge on the subject, but who did not fit into any of the other categories. |

| 7 | Where there is overlap between two concepts in responses by informants, both codes were counted separately. |

| 8 | Overall number of interviewees in this category. |

| 9 | Percentage of Category 2 interviewees overall. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | ‘Asian values’ journalism is a type of development journalism, in which an engagement with ideas like democracy or freedom of speech is subjugated to the interests of economic expansion and development (Edeani 1993; Wimmer and Wolf 2005). The likes of Okigbo (1985) and Blake (1997) have shown how a press with these characteristics can be manipulated into becoming a government mouthpiece. |

| Local Cambodian Trainer (TL) | 8 |

| International trainer (TI) | 8 |

| Donor (DR) | 6 |

| Expert Commentator (EC)6 | 3 |

| TOTAL | 25 |

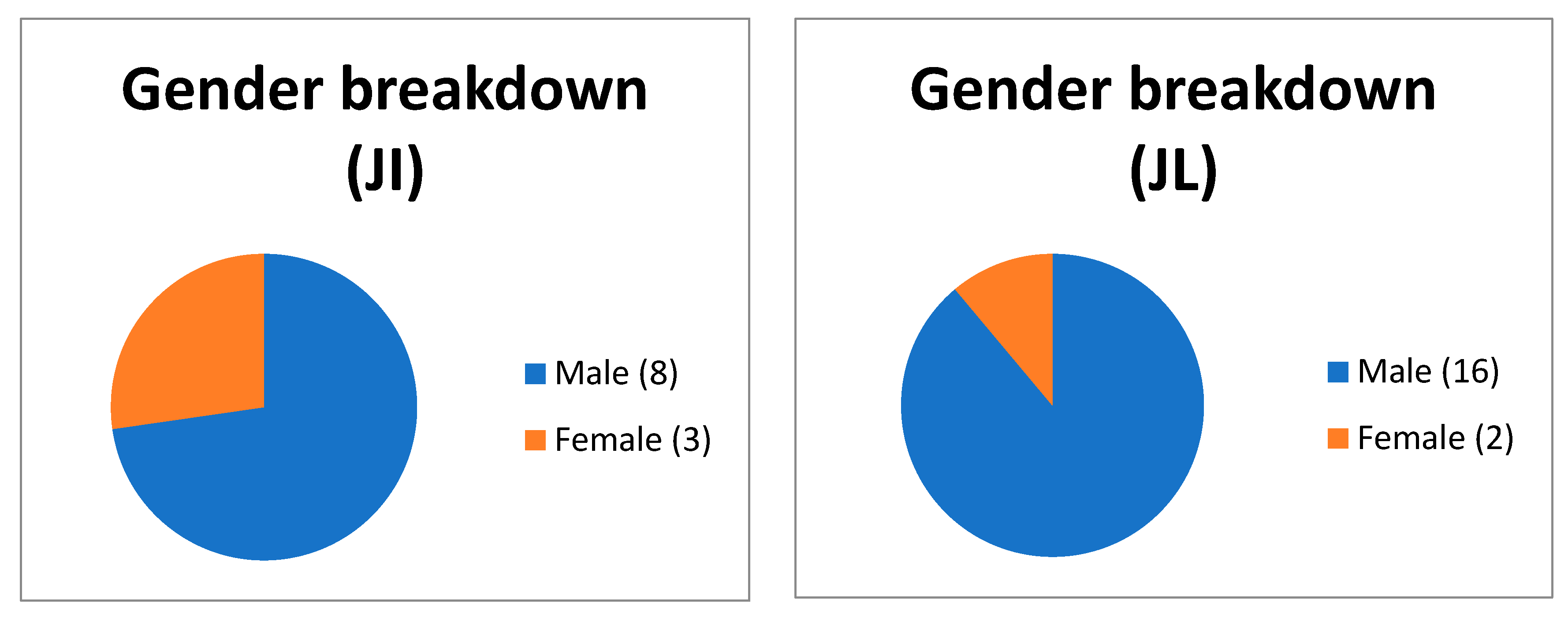

| Journalists working in local Khmer language media (JL) | 18 |

| Journalists working in International English language media (JI) | 11 |

| TOTAL | 29 |

| Subtheme | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Inform | Giving the public key information they need to make better choices |

| Affect change (general) | This means a core function of journalism is to affect change in a broad, non specific sense |

| Watchdog | This refers to a monitorial role, where the press promotes government transparency and accountability via public scrutiny of decision-makers |

| Improve democracy | Emphasis here is that function of press is to improve the level of democracy in Cambodia |

| Improve society | Sees journalism as something which improves society |

| Improve the government | See journalism as providing information that helps to improve general levels of governance |

| Exert political influence | This categorisation sees journalism as something which is explicitly political |

| Encourage free market | The emphasis here is on journalism as something that helps encourage business or trade |

| Encourage development | This sees journalism as having a role in infrastructural and general development of the country as a means of making the country stronger for all |

| Improve popular participation | A broader conceptualisation of ‘improving democracy’, this description placed journalism explicitly as something which encouraged popular participation in society |

| Advocate | In this instance meaning function of representing and promoting particular causes |

| Educate | Journalism described as having key educational function |

| Bridge | Meaning the press facilitates dialogue between the Government and the public |

| Improve human rights | This sees journalism as something that encourages better adherence to human rights. |

| Attack government | Informants here describe journalism as having a specific function to be critical, or attack the government |

| TI 88 | TL 8 | DR 6 | EC 3 | Overall 25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inform | 5 (62%) | 5 (62%) | 4 (67%) | 2 (67%) | 16 (60%)9 |

| Improve democracy | 4 (50%) | 3 (38%) | 5 (83%) | 2 (67%) | 14 (56%) |

| Watchdog | 3 (38%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (36%) |

| Affect change (general) | 1 (13%) | 5 (62%) | 2 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (32%) |

| Improve Society | 2 (25%) | 4 (50%) | 2 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (32%) |

| Improve human rights | 2 (25%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (67%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (32%) |

| Improve the government | 1 (13%) | 3 (38%) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (28%) |

| Exert political influence | 1 (13%) | 4 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (20%) |

| Encourage free market | 1 (13%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (16%) | 1 (33%) | 5 (20%) |

| Encourage development | 0 (0%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (20%) |

| Bridge | 0 (0%) | 3 (38%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (33%) | 4 (16%) |

| Improve popular participation | 0 (0%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (12%) |

| Advocate | 0 (0%) | 1 (13%) | 1 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) |

| JI (11) | JL (18) | Overall (29) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inform | 8 (73%) | 16 (89%) | 24 (82%) |

| Affect change | 8 (73%) | 13 (72%) | 21 (72%) |

| Improve democracy | 9 (82%) | 9 (50%) | 18 (62%) |

| Bridge | 4 (36%) | 7 (39%) | 11 (37%) |

| Watchdog | 3 (27%) | 7 (39%) | 10 (34%) |

| Educate | 2 (18%) | 7 (39%) | 9 (31%) |

| Improve human rights | 3 (27%) | 4 (22%) | 7 (24%) |

| Attack government | 2 (18%) | 5 (28%) | 7 (24%) |

| Improve society | 2 (18%) | 3 (17%) | 5 (17%) |

| Help development/promote Asian values | 0 (0%) | 4 (22%) | 4 (13%) |

| Exert political influence | 1 (9%) | 3 (17%) | 4 (13%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quinn, F. An Examination of the Interaction of Democratic Ideals with Journalism Training Programmes in the Global South: The Case of Cambodia. Journal. Media 2020, 1, 159-176. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010011

Quinn F. An Examination of the Interaction of Democratic Ideals with Journalism Training Programmes in the Global South: The Case of Cambodia. Journalism and Media. 2020; 1(1):159-176. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuinn, Fergal. 2020. "An Examination of the Interaction of Democratic Ideals with Journalism Training Programmes in the Global South: The Case of Cambodia" Journalism and Media 1, no. 1: 159-176. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010011

APA StyleQuinn, F. (2020). An Examination of the Interaction of Democratic Ideals with Journalism Training Programmes in the Global South: The Case of Cambodia. Journalism and Media, 1(1), 159-176. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia1010011