Who Is Gaining, Who Is Losing? Examining Benefit Sharing Mechanism (BSM) under REDD+ in India †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. REDD+ in Indian Context

3. Materials and Methods

4. Discussion

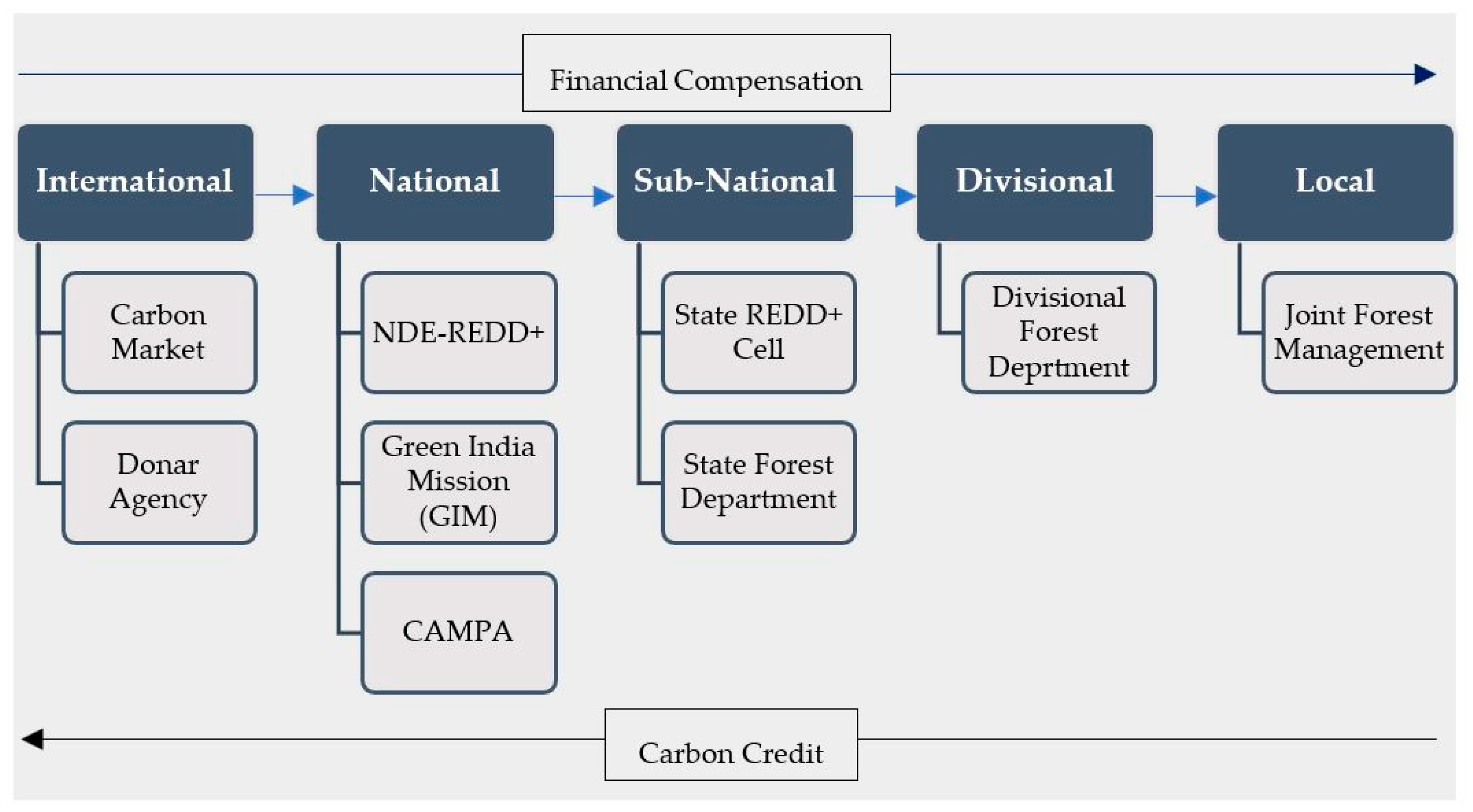

4.1. Institutional Structure of BSM in India

4.2. Problem and Prospect of Livelihood Enhancement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lederer, M. From CDM to REDD+—What Do We Know for Setting up Effective and Legitimate Carbon Governance? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1900–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos Lima, M.G.; Kissinger, G.; Visseren-Hamakers, I.J.; Braña-Varela, J.; Gupta, A. The Sustainable Development Goals and REDD+: Assessing Institutional Interactions and the Pursuit of Synergies. Int. Environ. Agreem. 2017, 17, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REDD+—Home. Available online: https://redd.unfccc.int/ (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Negi, S.; Giessen, L. India in International Climate Governance: Through Soft Power from REDD to REDD+ Policy in Favor of Relative Gains. For. Soc. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Database on REDD+ Projects. Available online: https://www.reddprojectsdatabase.org/view/projects.php?id=356&name=India&type=project (accessed on 3 October 2022).

- Ravindranath, N.H.; Murthy, I.K. Greening India Mission. Curr. Sci. 2010, 99, 444–449. [Google Scholar]

- MoEFCC. National REDD+ Strategy INDIA; Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change: New Delhi, India, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FSI. India State of Forest Report 2021; Forest Survey of India: Dehradun, India, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hajer, M.A. Discourse Analysis. In The Politics of Environmental Discourse; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 42–72. ISBN 978-0-19-829333-0. [Google Scholar]

- Den Besten, J.; Arts, B.; Behagel, J. Spiders in the Web: Understanding the Evolution of REDD+ in Southwest Ghana. Forests 2019, 10, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, N. Unpacking the “Joint” in Joint Forest Management. Dev. Chang. 2000, 31, 255–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, J.; Webb, E.L.; Agrawal, A. Does REDD+ Threaten to Recentralize Forest Governance? Science 2010, 328, 312–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijge, M.J.; Gupta, A. Framing REDD+ in India: Carbonizing and Centralizing Indian Forest Governance? Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 38, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosh, S. REDD+ in India, and India’s First REDD+ Project: A Critical Examination. Mausam 2011, 3, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Aggrawal, A. Neo-Liberal Conservation : Analysing Carbon Forestry and Its Challenges in India|Economic and Political Weekly. Econ. Political Wkly. 2019, 33–40, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bayrak, M.; Marafa, L. Ten Years of REDD+: A Critical Review of the Impact of REDD+ on Forest-Dependent Communities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sohel, A.; Naz, F.; Das, B. Who Is Gaining, Who Is Losing? Examining Benefit Sharing Mechanism (BSM) under REDD+ in India. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 22, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2022-13057

Sohel A, Naz F, Das B. Who Is Gaining, Who Is Losing? Examining Benefit Sharing Mechanism (BSM) under REDD+ in India. Environmental Sciences Proceedings. 2022; 22(1):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2022-13057

Chicago/Turabian StyleSohel, Amir, Farhat Naz, and Bidhan Das. 2022. "Who Is Gaining, Who Is Losing? Examining Benefit Sharing Mechanism (BSM) under REDD+ in India" Environmental Sciences Proceedings 22, no. 1: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2022-13057

APA StyleSohel, A., Naz, F., & Das, B. (2022). Who Is Gaining, Who Is Losing? Examining Benefit Sharing Mechanism (BSM) under REDD+ in India. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 22(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/IECF2022-13057