Environmental and Water-Use Efficiency of Indirect Evaporative Coolers in Southern Europe †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Description of IEC Evaluation

2.3. IEC Evaluation Indexes

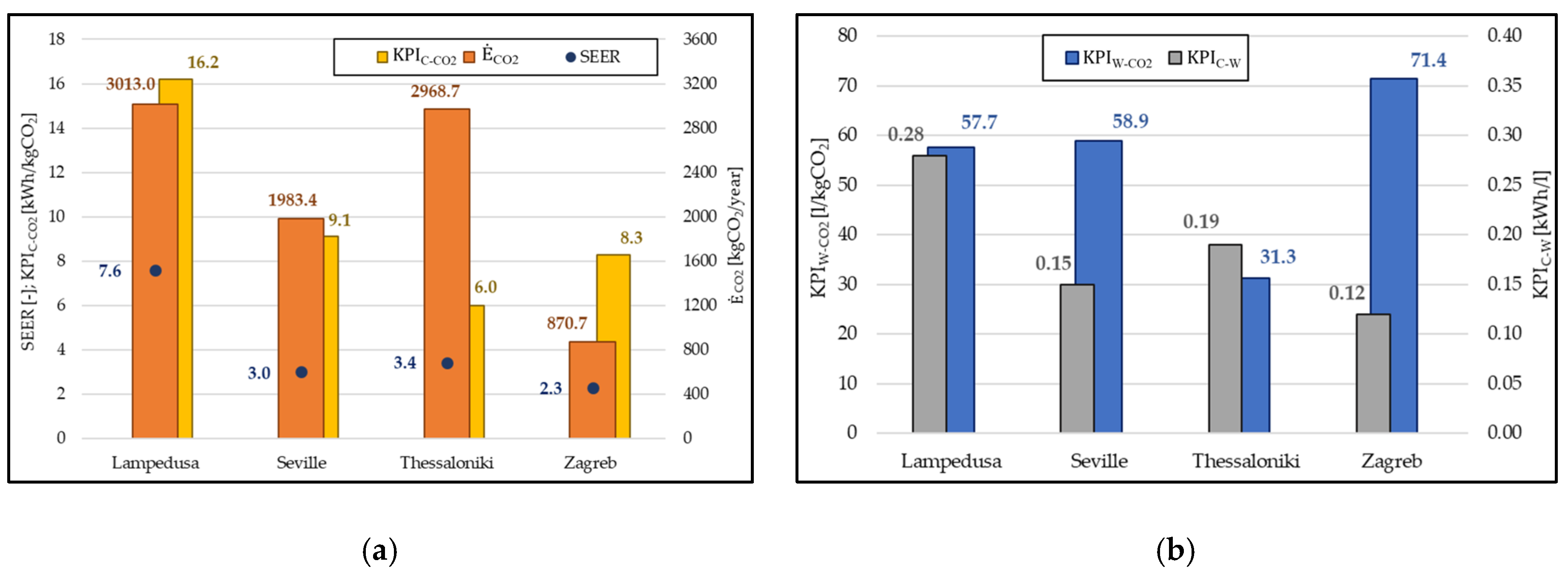

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Experimental Results

3.2. Annual Results of Environmental Impact

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohammed, R.H.; El-Morsi, M.; Abdelaziz, O. Indirect evaporative cooling for buildings: A comprehensive patents review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, R.; Shah, N.; Phadke, A. Addressing Water Consumption of Evaporative Coolers with Greywather; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pistochini, T.; Modera, M. Water-use efficiency for alternative cooling technologies in arid climates. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lara, M.J.; Comino, F.; Ruiz de Adana, M. Seasonal analysis comparison of three air-cooling systems in terms of thermal comfort, air quality and energy consumption for school buildings in Mediterranean climates. Energies 2021, 14, 4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Nominal cooling capacity | 18 | kW |

| Nominal inlet air flow rate | 5000 | m3 h−1 |

| 0.45 | - | |

| Nominal power consumption | 1.5 | kW |

| Maximum water consumption | 44 | l h−1 |

| Test | TIA (°C) | ωIA (g/kg) | (m3/h) | REX (-) | Test | TIA (°C) | ωIA (g/kg) | (m3/h) | REX (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 32 | 11 | 3000 | 0.3 | N6 | 40 | 11 | 3700 | 0.7 |

| N2 | 32 | 8 | 3000 | 0.5 | N7 | 32 | 11 | 4500 | 0.3 |

| N3 | 32 | 11 | 3000 | 0.7 | N8 | 32 | 14 | 4500 | 0.5 |

| N4 | 40 | 11 | 3700 | 0.3 | N9 | 32 | 11 | 4500 | 0.7 |

| N5 | 40 | 8 | 3700 | 0.5 |

| Test | cooling (kW) | cons (kW) | W (L/h) | Test | cooling (kW) | cons (kW) | W (L/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 17.5 | 0.377 | 14.6 | N6 | 22.2 | 0.669 | 43.7 |

| N2 | 16.7 | 0.399 | 21.3 | N7 | 33.5 | 1.130 | 17.2 |

| N3 | 13.3 | 0.376 | 37.8 | N8 | 26.8 | 1.126 | 40.8 |

| N4 | 30.0 | 0.692 | 17.3 | N9 | 24.3 | 1.079 | 42.5 |

| N5 | 28.3 | 0.703 | 23.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Lara, M.J.; Comino, F.; Ruiz de Adana, M. Environmental and Water-Use Efficiency of Indirect Evaporative Coolers in Southern Europe. Environ. Sci. Proc. 2022, 18, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022018013

Romero-Lara MJ, Comino F, Ruiz de Adana M. Environmental and Water-Use Efficiency of Indirect Evaporative Coolers in Southern Europe. Environmental Sciences Proceedings. 2022; 18(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022018013

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Lara, María Jesús, Francisco Comino, and Manuel Ruiz de Adana. 2022. "Environmental and Water-Use Efficiency of Indirect Evaporative Coolers in Southern Europe" Environmental Sciences Proceedings 18, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022018013

APA StyleRomero-Lara, M. J., Comino, F., & Ruiz de Adana, M. (2022). Environmental and Water-Use Efficiency of Indirect Evaporative Coolers in Southern Europe. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 18(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/environsciproc2022018013