Environmental Impacts and Sustainability of Nanomaterials in Water and Soil Systems †

Abstract

1. Introduction

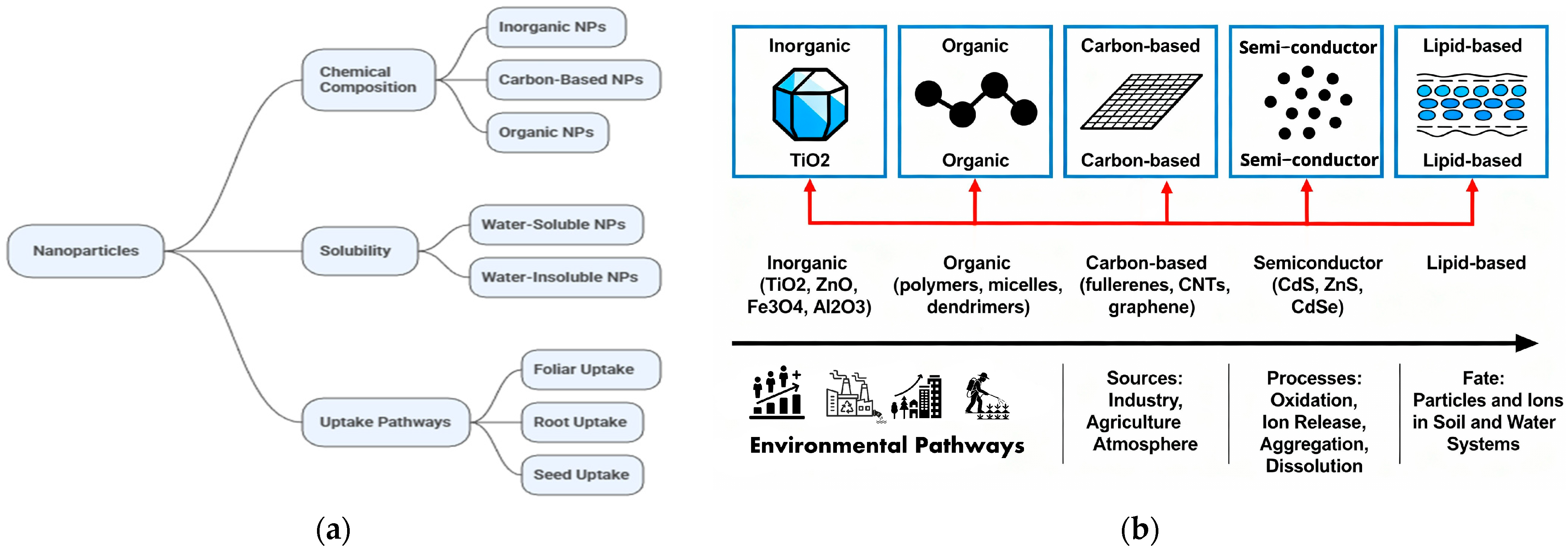

2. Classification and Environmental Pathways of Nanomaterials

Major Nanomaterials in the Environment

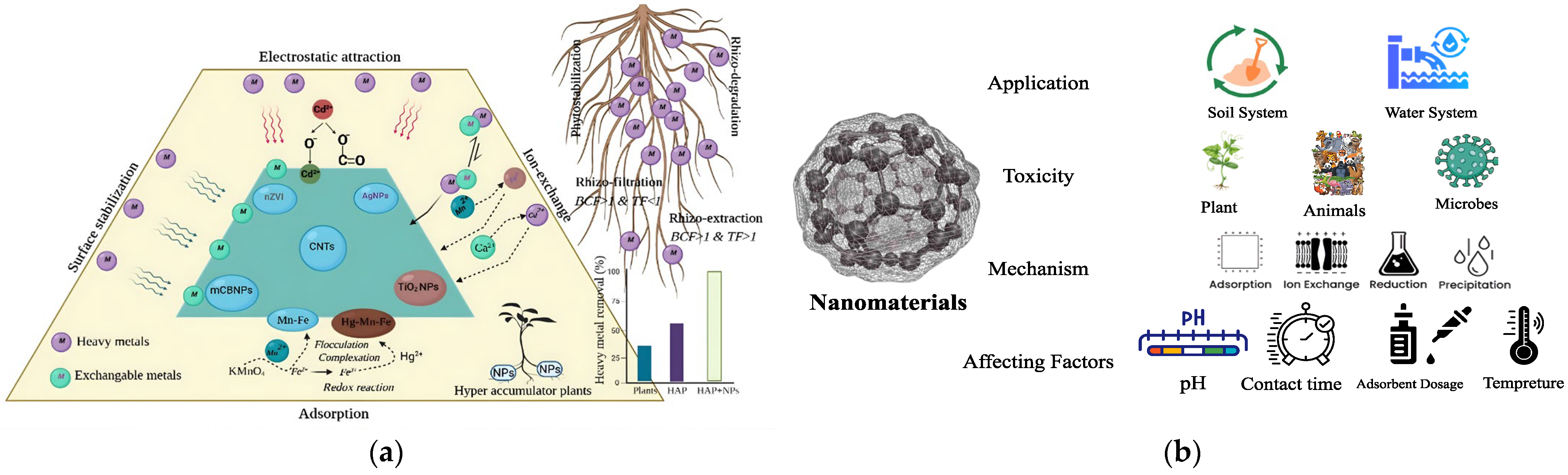

3. Environmental Impacts of Nanomaterials

3.1. Impact on Water System

3.2. Impact on Soil System

4. Beneficial Roles and Sustainable Geotechnical Applications

Green-Synthesized Nanomaterials and Environmental Fate

5. Nanotoxicity in the Water and Soil System

6. Risk Assessment and Regulatory Considerations

6.1. Ecotoxicological Assessment of Engineered Nanomaterials

6.2. Regulatory Perspectives and Policy Frameworks

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alazaiza, M.Y.D.; Albahnasawi, A.; Ali, G.A.M.; Bashir, M.J.K.; Copty, N.K.; Amr, S.S.A.; Abushammala, M.F.M.; Al Maskari, T. Recent Advances of Nanoremediation Technologies for Soil and Groundwater Remediation: A Review. Water 2021, 13, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batley, G.E.; Kirby, J.K.; McLaughlin, M.J. Fate and Risks of Nanomaterials in Aquatic and Terrestrial Environments. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalili, Z. Metal Oxides Nanoparticles: General Structural Description, Chemical, Physical, and Biological Synthesis Methods, Role in Pesticides and Heavy Metal Removal through Wastewater Treatment. Molecules 2023, 28, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, E.R.; Ramsdorf, W.A.; Lotti Domingos, L.M.; De Souza Miranda, L.P.; Mattoso Filho, N.P.; Cestari, M.M. Ecotoxicological Effects of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) on Aquatic Organisms: Current Research and Emerging Trends. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; McDonald, T.J.; Sohn, M.; Anquandah, G.A.K.; Pettine, M.; Zboril, R. Assessment of Toxicity of Selenium and Cadmium Selenium Quantum Dots: A Review. Chemosphere 2017, 188, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, C.; Jiang, M.; Xiang, Q.; Wang, S.; Su, Y.; Zhang, N.; Si, Z.; Mu, Y.; Yang, R. Dissolved Organic Matter Mitigates the Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles to Freshwater Algae: Effects on Oxidative Stress and Membrane Function. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 125973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadishad, B.; Chahal, S.; Akbari, A.; Cianciarelli, V.; Azodi, M.; Ghoshal, S.; Tufenkji, N. Amendment of Agricultural Soil with Metal Nanoparticles: Effects on Soil Enzyme Activity and Microbial Community Composition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1908–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsh, H.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Rasheed, R.M.; Almajed, A. State-of-the-Art Review on the Role and Applicability of Select Nano-Compounds in Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Applications. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 4149–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.S.; Shedbalkar, U.U.; Truskewycz, A.; Chopade, B.A.; Ball, A.S. Nanoparticles for Environmental Clean-up: A Review of Potential Risks and Emerging Solutions. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2016, 5, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-Y.; Su, W.-H. Classification, Uptake, Translocation, and Detection Methods of Nanoparticles in Crop Plants: A Review. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 1847–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamini, V.; Shanmugam, V.; Rameshpathy, M.; Venkatraman, G.; Ramanathan, G.; Al Garalleh, H.; Hashmi, A.; Brindhadevi, K.; Devi Rajeswari, V. Environmental Effects and Interaction of Nanoparticles on Beneficial Soil and Aquatic Microorganisms. Environ. Res. 2023, 236, 116776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachapur, V.L.; Dalila Larios, A.; Cledón, M.; Brar, S.K.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R.Y. Behavior and Characterization of Titanium Dioxide and Silver Nanoparticles in Soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 563–564, 933–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibyanshu, K.; Chhaya, T.; Raychoudhury, T. A Review on the Fate and Transport Behavior of Engineered Nanoparticles: Possibility of Becoming an Emerging Contaminant in the Groundwater. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 4649–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irumva, O.; Twagirayezu, G.; Xia, A.; Uwimpaye, F.; Nizeyimana, J.C.; Nizeyimana, I.; Uwimana, A.; Birame, C.S. Environmental Fate, Transport, Impacts, and Future Perspectives of Engineered Nanoparticles in Surface Waters. Environ. Res. 2025, 285, 122267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaniv, D.; Dror, I.; Berkowitz, B. Effects of Particle Size and Surface Chemistry on Plastic Nanoparticle Transport in Saturated Natural Porous Media. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besseling, E.; Quik, J.T.K.; Sun, M.; Koelmans, A.A. Fate of Nano- and Microplastic in Freshwater Systems: A Modeling Study. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giese, B.; Klaessig, F.; Park, B.; Kaegi, R.; Steinfeldt, M.; Wigger, H.; Von Gleich, A.; Gottschalk, F. Risks, Release and Concentrations of Engineered Nanomaterial in the Environment. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschalk, F.; Sun, T.; Nowack, B. Environmental Concentrations of Engineered Nanomaterials: Review of Modeling and Analytical Studies. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 181, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.Y.; Gottschalk, F.; Hungerbühler, K.; Nowack, B. Comprehensive Probabilistic Modelling of Environmental Emissions of Engineered Nanomaterials. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 185, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.Y.; Bornhöft, N.A.; Hungerbühler, K.; Nowack, B. Dynamic Probabilistic Modeling of Environmental Emissions of Engineered Nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 4701–4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazari, S.A.; Ali, E.; Abro, R.; Khan, F.S.A.; Ahmed, I.; Ahmed, M.; Nizamuddin, S.; Siddiqui, T.H.; Hossain, N.; Mubarak, N.M.; et al. Nanomaterials: Applications, Waste-Handling, Environmental Toxicities, and Future Challenges—A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lead, J.R.; Batley, G.E.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Croteau, M.-N.; Handy, R.D.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Judy, J.D.; Schirmer, K. Nanomaterials in the Environment: Behavior, Fate, Bioavailability, and Effects—An Updated Review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2029–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z. Nano-CeO2 Exhibits Adverse Effects at Environmental Relevant Concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 3725–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Yousaf, B.; Ullah, H.; Ali, M.U.; Ok, Y.S.; Rinklebe, J. Environmental Transformation and Nano-Toxicity of Engineered Nano-Particles (ENPs) in Aquatic and Terrestrial Organisms. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 2523–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Zhang, Y.; Farghali, M.; Rashwan, A.K.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Mohamed, I.M.A.; Badr, M.M.; Ihara, I.; Rooney, D.W.; et al. Synthesis of Green Nanoparticles for Energy, Biomedical, Environmental, Agricultural, and Food Applications: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 841–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tończyk, A.; Niedziałkowska, K.; Lisowska, K. Ecotoxic Effect of Mycogenic Silver Nanoparticles in Water and Soil Environment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, F.; Kost, E.; Nowack, B. Engineered Nanomaterials in Water and Soils: A Risk Quantification Based on Probabilistic Exposure and Effect Modeling. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2013, 32, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Chen, G.; Zeng, G.; Peng, M.; Huang, Z.; Shi, J.; Huang, T. Stability, Transport and Ecosystem Effects of Graphene in Water and Soil Environments. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5370–5388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ou, Q.; Van Der Hoek, J.P.; Liu, G.; Lompe, K.M. Photo-Oxidation of Micro- and Nanoplastics: Physical, Chemical, and Biological Effects in Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sathish, T.; Ahalya, N.; Thirunavukkarasu, M.; Senthil, T.S.; Hussain, Z.; Haque Siddiqui, M.I.; Panchal, H.; Kumar Sadasivuni, K. A Comprehensive Review on the Novel Approaches Using Nanomaterials for the Remediation of Soil and Water Pollution. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 86, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Kang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, M. Behavior, Remediation Effect and Toxicity of Nanomaterials in Water Environments. Environ. Res. 2019, 174, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selck, H.; Handy, R.D.; Fernandes, T.F.; Klaine, S.J.; Petersen, E.J. Nanomaterials in the Aquatic Environment: A European Union–United States Perspective on the Status of Ecotoxicity Testing, Research Priorities, and Challenges Ahead. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2016, 35, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Baalousha, M.; Chen, J.; Chaudry, Q.; Von Der Kammer, F.; Kuhlbusch, T.A.J.; Lead, J.; Nickel, C.; Quik, J.T.K.; Renker, M.; et al. A Review of the Properties and Processes Determining the Fate of Engineered Nanomaterials in the Aquatic Environment. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 45, 2084–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.M.; Briffa, S.M.; Mazzonello, A.; Valsami-Jones, E. A Review of the Aquatic Environmental Transformations of Engineered Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, U.U.; Humayun, M.; Ghani, U.; Usman, M.; Ullah, H.; Khan, A.; El-Metwaly, N.M.; Khan, A. MXenes as Emerging Materials: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 4909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, H.; Zaidi, S.J. Developments in the Application of Nanomaterials for Water Treatment and Their Impact on the Environment. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikula, K.; Johari, S.A.; Santos-Oliveira, R.; Golokhvast, K. Joint Toxicity and Interaction of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials with Co-Existing Pollutants in Aquatic Environments: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liang, D.; Wang, Y.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Monikh, F.A.; Zhao, X.; Dong, Z.; Fan, W. A Critical Review on the Biological Impact of Natural Organic Matter on Nanomaterials in the Aquatic Environment. Carbon Res. 2022, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, T.L.; Mestre, N.C.; Sabóia-Morais, S.M.T.; Bebianno, M.J. Environmental Behaviour and Ecotoxicity of Quantum Dots at Various Trophic Levels: A Review. Environ. Int. 2017, 98, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Tong, X.; Li, K.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y. Behavior and Potential Impacts of Metal-Based Engineered Nanoparticles in Aquatic Environments. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avant, B.; Bouchard, D.; Chang, X.; Hsieh, H.-S.; Acrey, B.; Han, Y.; Spear, J.; Zepp, R.; Knightes, C.D. Environmental Fate of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene Oxide across Different Aquatic Ecosystems. NanoImpact 2019, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.T.; Motta, E.; Daniel, D.; Nunes, B.; Neves, J. Ecotoxicological Effects of Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Nickel Nanoparticles on Aquatic Organisms from Three Trophic Levels: Insights from Oxidative Stress Biomarkers. JoX 2025, 15, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, K.; Kohli, S.K.; Handa, N.; Kaur, H.; Ohri, P.; Bhardwaj, R.; Yousaf, B.; Rinklebe, J.; Ahmad, P. Enthralling the Impact of Engineered Nanoparticles on Soil Microbiome: A Concentric Approach towards Environmental Risks and Cogitation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 222, 112459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Kumari, S.; Singh, N.; Khan, S. Fate of Plastic Nanoparticles (PNPs) in Soil and Plant Systems: Current Status & Research Gaps. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2023, 11, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suazo-Hernández, J.; Arancibia-Miranda, N.; Mlih, R.; Cáceres-Jensen, L.; Bolan, N.; Mora, M.D.L.L. Impact on Some Soil Physical and Chemical Properties Caused by Metal and Metallic Oxide Engineered Nanoparticles: A Review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qiu, T.; Huang, F.; Zeng, Y.; Cui, Y.; Chen, J.; White, J.C.; Fang, L. Micro/Nanoplastics Pollution Poses a Potential Threat to Soil Health. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, E.; El-shahawy, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Abd El-Halim, A.E.-H.A.; Abo-Ogiala, A.; Shokr, M.S.; Mohamed, E.S.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Ismail, S.M. Enhancing Maize Yield and Soil Health through the Residual Impact of Nanomaterials in Contaminated Soils to Sustain Food. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M.S.; Filser, J. Impacts of Metal-Based Engineered Nanomaterials on Soil Communities. Environ. Sci. Nano 2016, 3, 506–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Yang, X. How to Safeguard Soil Health against Silver Nanoparticles through a Microbial Functional Gene-Based Approach? Environ. Int. 2025, 202, 109680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Yang, B.; Wang, H.; Cao, X.; He, F.; Wang, L. Reveal Molecular Mechanism on the Effects of Silver Nanoparticles on Nitrogen Transformation and Related Functional Microorganisms in an Agricultural Soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, I.; Lee, M.; Tran, A.T.P.; Lee, S.; Kwon, Y.-M.; Im, J.; Cho, G.-C. Review on Biopolymer-Based Soil Treatment (BPST) Technology in Geotechnical Engineering Practices. Transp. Geotech. 2020, 24, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağrıaçık, B.; Mahmutluoğlu, B.; Topoliński, S. Improvements to Load-Bearing Capacity and Settlement of Clay Soil After Adding Nano-MgO and Fibers. Polymers 2025, 17, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bağrıaçık, B.; Mahmutluoğlu, B.; Ürünveren, A. A Comprehensive Study on the Assessment of CaCO3-, Nano-CaCO3-, and Glass Fiber Chopped Strand (GFCS)-Treated Clay in Terms of Bearing Capacity and Settlement Enhancements. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, M.; Guo, W.; Luo, Q. Comparison of Nanomaterials with Other Unconventional Materials Used as Additives for Soil Improvement in the Context of Sustainable Development: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales, J.; Agrela, F.; Marcobal, J.R.; Diaz-López, J.L.; Cuenca-Moyano, G.M.; Caballero, Á.; Cabrera, M. Use of Nanomaterials in the Stabilization of Expansive Soils into a Road Real-Scale Application. Materials 2020, 13, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Kumari, A.; Ranjan, A.; Mandzhieva, S.; Sushkova, S.; Singh, R.K.; Verma, K.K. Nanotechnology in the Restoration of Polluted Soil. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorth, R.; Coutris, C.; Nguyen, N.H.A.; Sevcu, A.; Gallego-Urrea, J.A.; Baun, A.; Joner, E.J. Ecotoxicity Testing and Environmental Risk Assessment of Iron Nanomaterials for Sub-Surface Remediation—Recommendations from the FP7 Project NanoRem. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vineeth Kumar, C.M.; Karthick, V.; Kumar, V.G.; Inbakandan, D.; Rene, E.R.; Suganya, K.S.U.; Embrandiri, A.; Dhas, T.S.; Ravi, M.; Sowmiya, P. The Impact of Engineered Nanomaterials on the Environment: Release Mechanism, Toxicity, Transformation, and Remediation. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Boora, A.; Thakur, A.; Gupta, T.K. Green and Sustainable Synthesis of Nanomaterials: Recent Advancements and Limitations. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Mofijur, M.; Rafa, N.; Chowdhury, A.T.; Chowdhury, S.; Nahrin, M.; Islam, A.B.M.S.; Ong, H.C. Green Approaches in Synthesising Nanomaterials for Environmental Nanobioremediation: Technological Advancements, Applications, Benefits and Challenges. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Sarkar, B.; Khan, E.; Alessi, D.S.; Biswas, J.K.; Manjaiah, K.M.; Eguchi, M.; Wu, K.C.W.; Yamauchi, Y.; Ok, Y.S. Nanomaterials for Sustainable Remediation of Chemical Contaminants in Water and Soil. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 2611–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, I.; Venditti, I.; Trotta, F.; Punta, C. Environmental Safety of Nanotechnologies: The Eco-Design of Manufactured Nanomaterials for Environmental Remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devasena, T.; Iffath, B.; Renjith Kumar, R.; Muninathan, N.; Baskaran, K.; Srinivasan, T.; John, S.T. Insights on the Dynamics and Toxicity of Nanoparticles in Environmental Matrices. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2022, 2022, 4348149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Adam, V.; Nowack, B. Form-Specific and Probabilistic Environmental Risk Assessment of 3 Engineered Nanomaterials (Nano-Ag, Nano-TiO2, and Nano-ZnO) in European Freshwaters. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 2629–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwirn, K.; Voelker, D.; Galert, W.; Quik, J.; Tietjen, L. Environmental Risk Assessment of Nanomaterials in the Light of New Obligations Under the REACH Regulation: Which Challenges Remain and How to Approach Them? Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2020, 16, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingeri, A.; Ale, A.; Rusconi, T.; Scattoni, M.; Lemaire, S.; Protano, G.; Venditti, I.; Corsi, I. Nanosilver Environmental Safety in Marine Organisms: Ecotoxicological Assessment of a Commercial Nano-Enabled Product vs. an Eco-Design Formulation. Toxics 2025, 13, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, A.; Slomberg, D.L.; Nassar, M.; Santaella, C.; Masion, A.; Rose, J.; Auffan, M. Aquatic Mesocosm Strategies for the Environmental Fate and Risk Assessment of Engineered Nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 16270–16282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Book, F.; Backhaus, T. Aquatic Ecotoxicity of Manufactured Silica Nanoparticles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, G.V.; Hotze, E.M.; Bernhardt, E.S.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Pedersen, J.A.; Wiesner, M.R.; Xing, B. Environmental Occurrences, Behavior, Fate, and Ecological Effects of Nanomaterials: An Introduction to the Special Series. J. Environ. Qual. 2010, 39, 1867–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcon, L.; Oliveras, J.; Puntes, V.F. In Situ Nanoremediation of Soils and Groundwaters from the Nanoparticle’s Standpoint: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 791, 148324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, I.; Bellingeri, A.; Eliso, M.C.; Grassi, G.; Liberatori, G.; Murano, C.; Sturba, L.; Vannuccini, M.L.; Bergami, E. Eco-Interactions of Engineered Nanomaterials in the Marine Environment: Towards an Eco-Design Framework. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nthunya, L.N.; Mosai, A.K.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Bopape, M.; Dhibar, S.; Nuapia, Y.; Ajiboye, T.O.; Buledi, J.A.; Solangi, A.R.; Sherazi, S.T.H.; et al. Unseen threats in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems: Nanoparticle persistence, transport and toxicity in natural environments. Chemosphere 2025, 382, 144470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Ullah, S.; Abdi, G.; Shah, G.M.; Zaman, W.; Ayaz, A. Agriculture and Environmental Management through Nanotechnology: Eco-Friendly Nanomaterial Synthesis for Soil-Plant Systems, Food Safety, and Sustainability. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, R.W.S.; Yeung, K.W.Y.; Yung, M.M.N.; Djurišić, A.B.; Giesy, J.P.; Leung, K.M.Y. Regulation of Engineered Nanomaterials: Current Challenges, Insights and Future Directions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 3060–3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigger, H.; Kägi, R.; Wiesner, M.; Nowack, B. Exposure and Possible Risks of Engineered Nanomaterials in the Environment—Current Knowledge and Directions for the Future. Rev. Geophys. 2020, 58, e2020RG000710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, I.; Winther-Nielsen, M.; Sethi, R.; Punta, C.; Della Torre, C.; Libralato, G.; Lofrano, G.; Sabatini, L.; Aiello, M.; Fiordi, L.; et al. Ecofriendly Nanotechnologies and Nanomaterials for Environmental Applications: Key Issue and Consensus Recommendations for Sustainable and Ecosafe Nanoremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 154, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Teng, Y.; Luo, Y.; Kuramae, E.; Ren, W. Threats to the Soil Microbiome from Nanomaterials: A Global Meta and Machine-Learning Analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 188, 109248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristozov, D.R.; Gottardo, S.; Critto, A.; Marcomini, A. Risk Assessment of Engineered Nanomaterials: A Review of Available Data and Approaches from a Regulatory Perspective. Nanotoxicology 2012, 6, 880–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.R.; Kalangi, V.S. Water Purification. International Patent Application WO 2016/189320 A1, 1 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, V.F.; Griggs, C.S.; Mattei-Sosa, J.; Petery, B.; Gurtowski, L. Advanced Filtration Membranes Using Chitosan and Graphene Oxide. U.S. Patent US 10,596,525 B2, 24 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.; Zhang, M.; Yao, Y. Biochar/Metal Composites, Methods of Making Biochar/Metal Composites, and Methods of Removing Contaminants from Water. International Patent Application WO 2013/126477 A1, 29 August 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bezbaruah, A.N.; Almeelbi, T.B.; Quamme, M.; Kahn, E. Calcium-Alginate Entrapped Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron. International Patent Application WO 2014/168728 A1, 16 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Nanomaterials | Major Uses and Challenges | Production | Concentration Range | Environmental System and Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag NPs | Antimicrobial textiles, medical devices, water treatment; High uncertainty release, and transformation. | 500 tons/year | Surface waters: ng/L; Soils: ng/kg to mg/kg | Soil and water; Toxicity mainly via Ag+ ion release, causing oxidative stress and microbial disruption [17,18]. |

| TiO2 NPs | Cosmetics, paints, photocatalysis; Analytical detection limits, fate modeling uncertainties. | About 10,000–100,000 tons | Surface waters: pg-ng/L; Soils: µg/kg to mg/kg | Surface waters and soils; Low to moderate toxicity, aggregation, and sedimentation affect [19,20]. |

| Nanoplastics | Plastic degradation products, consumer goods; Complex environmental behavior. | - | Water: ng/L to µg/L; Soils: ng/kg. | Water and soil; Physical and chemical toxicity, bioaccumulation, interaction with organic matter affecting mobility [21,22]. |

| Carbon-based | Electronics, composites, energy storage; Lack of standardized detection methods | Hundreds to thousands of tons/year | Water: pg L−1 to ng L−1; Soils: ng kg−1 to µg kg−1. | Surface water and soil; Limited dissolution, transport controlled by aggregation and deposition, potential physical effects on organisms [22,23]. |

| CeO2 NPs | Catalysts, fuel additives; High uncertainty in release estimates and environmental fate | - | Soils: µg kg−1 to mg kg−1; Water: low ng L−1 to µg L−1. | Soil and water: low toxicity, potential oxidative stress effects, localized risks near point sources [23,24]. |

| Nanomaterials | Key Properties/Functions | Impact on Water | Impact on Soil |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ag NPs | Antimicrobial and highly reactive | Toxic to aquatic organisms | Disrupt soil microbial communities [26] |

| TiO2 NPs | Stable and high surface area | Toxic to algae and aquatic organisms | Alters soil microbial, and toxic to plants [27] |

| ZnO NPs | High dissolution and UV-absorbing | Toxic to aquatic organisms | Alters soil enzyme, inhibits microbials [27] |

| Carbon-based NPs | High surface area and adsorptive | Potential for bioaccumulation | Toxic to fauna and flora [28] |

| Micro/nanoplastics | Persistent and hydrophobic | Disrupts planktonic growth | Inhibits plant growth [29] |

| Nano-biochar | Porous and carbon-rich | Adsorbs organic and heavy metals | Adsorbs pollutants [30] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ridoy, M.N.; Supto, S.T.J. Environmental Impacts and Sustainability of Nanomaterials in Water and Soil Systems. Mater. Proc. 2025, 26, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025026006

Ridoy MN, Supto STJ. Environmental Impacts and Sustainability of Nanomaterials in Water and Soil Systems. Materials Proceedings. 2025; 26(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025026006

Chicago/Turabian StyleRidoy, Md. Nurjaman, and Sk. Tanjim Jaman Supto. 2025. "Environmental Impacts and Sustainability of Nanomaterials in Water and Soil Systems" Materials Proceedings 26, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025026006

APA StyleRidoy, M. N., & Supto, S. T. J. (2025). Environmental Impacts and Sustainability of Nanomaterials in Water and Soil Systems. Materials Proceedings, 26(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/materproc2025026006