Abstract

Municipal sewer networks span across large areas in cities around the world and require regular inspection to identify structural failures, blockages, and other issues that pose public health risks. Traditional inspection methods rely on remote-controlled robotic cameras or CCTV surveys performed by skilled inspectors. These processes are time-consuming, expensive, and often inconsistent; for example, the United States alone has more than 1.2 million miles of underground sewer pipes, and up to 75,000 failures are reported annually. Manual CCTV inspections can only cover a small fraction of the network each year, resulting in delayed discovery of defects and costly repairs. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a scalable and low-power fault detection system that integrates embedded machine vision and Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) on resource-constrained microcontrollers. The system uses transfer learning to train a lightweight TinyML model for defect classification using a dataset of sewer pipe images and deploys the model on battery-powered devices. Each device captures images inside the pipe, performs on-device inference to detect cracks, intrusions, debris, and other anomalies, and communicates inference results over a long-range LoRa radio link. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed system achieves 94% detection accuracy with sub-hundred-millisecond inference time and operates for extended periods on battery power. The research contributes a template for autonomous, scalable, and cost-effective sewer condition assessment that can help municipalities prioritize maintenance and prevent catastrophic failures.

1. Introduction

Sewerage infrastructure is among the most expensive and expansive public assets in modern society. For example, the United States has an estimated 1.2 million miles of sewer pipes, and up to 75,000 pipe failures are reported each year [1]. The scale of these networks makes routine inspection extremely challenging. In Australia, stormwater pipes constitute about 19% of local government infrastructure, yet only a small percentage of pipes are inspected annually because current practices rely on manual closed-circuit television (CCTV) surveys [2]. Similar issues are reported in Europe, where sewer networks such as Germany’s 608,000 km system are inspected only once every 10–15 years [3]. Delayed detection means that small defects can evolve into major collapses or blockages, releasing untreated wastewater into the environment and causing significant financial and societal damage. Manual inspections are labor-intensive, expensive, and prone to human error, and the monotony of reviewing long video recordings can result in overlooked defects. The National State of the Assets Report notes that 36% of public infrastructure assets in Australia are in poor or fair condition, and that inspection processes are largely labor-intensive and time-consuming.

Technological advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision offer an opportunity to automate defect detection. Recent studies have demonstrated deep learning models that identify and classify sewer defects from CCTV images [4]. These models include object detection networks such as EfficientDet-D0, which achieved an 83% detection rate on a dataset covering 14.7 km of sewer pipes, and instance-segmentation models based on YOLOv8, which reached a mean average precision (mAP@0.5) of 0.92 on stormwater pipe footage. However, existing research typically assumes ample computing resources and a reliable power supply. It also focuses on post-processing recorded videos rather than performing detection in real time.

This paper proposes a scalable sewer fault detection and condition assessment system that harnesses embedded machine vision and TinyML. The key contributions are as follows:

- Lightweight defect detection model: We train a compact convolutional neural network using transfer learning on a dataset derived from the Sewer-ML dataset and other publicly available sources. The model is compiled to TensorFlow Lite format and quantized to 8-bit integers to run efficiently on microcontrollers.

- Embedded sensor design: A battery-powered device integrates a camera, microcontroller, and LoRa transceiver. The device periodically captures images, performs on-device inference to classify defects, transmits compact inference results, and enters a low-power sleep mode. This architecture minimizes energy consumption and data transmission.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on sewer inspection, defect detection datasets, and TinyML for embedded vision. Section 3 details the proposed system, including hardware design, the dataset, and model development. Section 4 presents experimental results and discusses system performance. Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future work.

2. Related Work

Recent years have seen growing interest in complete automated systems for sewer condition monitoring that integrate sensing hardware, embedded intelligence, data communication, and autonomy. These systems aim to reduce reliance on manual inspections by combining imaging, robotics, real-time inference, and networked reporting into cohesive workflows for scalable and efficient infrastructure health assessments.

Jung et al. [3] presents a comprehensive robotic inspection setup integrating a camera array, front-mounted camera, and LiDAR to improve data quality in sewer inspection. Each sensor specializes in capturing certain types of damage, feeding into tailored deep learning models to enhance detection accuracy over traditional single-sensor systems. Liu et al. [5] develop a lightweight computer-vision framework for sewer inspection that marries defect detection and 3D reconstruction. Their Sewer-YOLO-Slim model prunes YOLOv7-tiny to achieve high accuracy (mAP = 93.5%) while reducing model size and computation, enabling real-time edge deployment. They add spatial context via multi-view 3D modeling built from robot-captured images. Yang et al. [6] demonstrate that TinyML can be deployed on miniature in-pipe robots using an ESP32 microcontroller. Their five-layer CNN achieves 97.1% feature detection accuracy with minimal RAM (195 kB) and flash usage, showcasing how embedded ML can enable autonomous on-device inspection under tight resource constraints. Ha et al. [4] annotate 14.7 km of sewer imagery, then use EfficientDet-D0 to detect defects. Their system achieves 83% detection accuracy, and importantly, the system architecture addresses practical challenges in defect annotation and training for real-world conditions—including rare but critical severe defects.

The PLIERS system [7] employs an IoT-enabled swarm of robots that traverse emptied sewer and water pipes, capture crack images, and communicate with a cloud-hosted CNN for crack detection and severity assessment. Their architecture demonstrates multi-robot coordination, onboard imaging, and centralized analysis showing one way to scale inspection via robotics and IoT. Antonini et al. [8] propose a fully adaptable edge-based anomaly detection system combining IoT, edge computing, and TinyML. Though not sewer-specific, the architecture aligns with embedded, networked sensing systems and offers a blueprint for future modular sewer inspection nodes. Utepov et al. [9] propose an LSMF (Live-Feed Sewer Monitoring Framework) that stitches together continuous video streaming, real-time analysis, and alerting—laying a blueprint for live, end-to-end monitoring systems. Otero et al. [10] apply SSL to sewer video data, achieving competitive defect detection with models that are five times smaller and using just 10% of the labeled data, highlighting promise in resource-constrained or data-limited contexts.

These diverse system-level studies reflect important advances in sensor fusion, embedded inference, robotics, live monitoring, and data-efficient learning. However, a compact, battery-powered, autonomous node that performs on-device defect detection and leverages low-power IoT (e.g., LoRa) for transmitting summarized alert data remains underexplored.

The proposed system consists of the following:

- TinyML vision model for embedded microcontrollers;

- Low-power LoRa connectivity.

3. Proposed Method

3.1. System Architecture

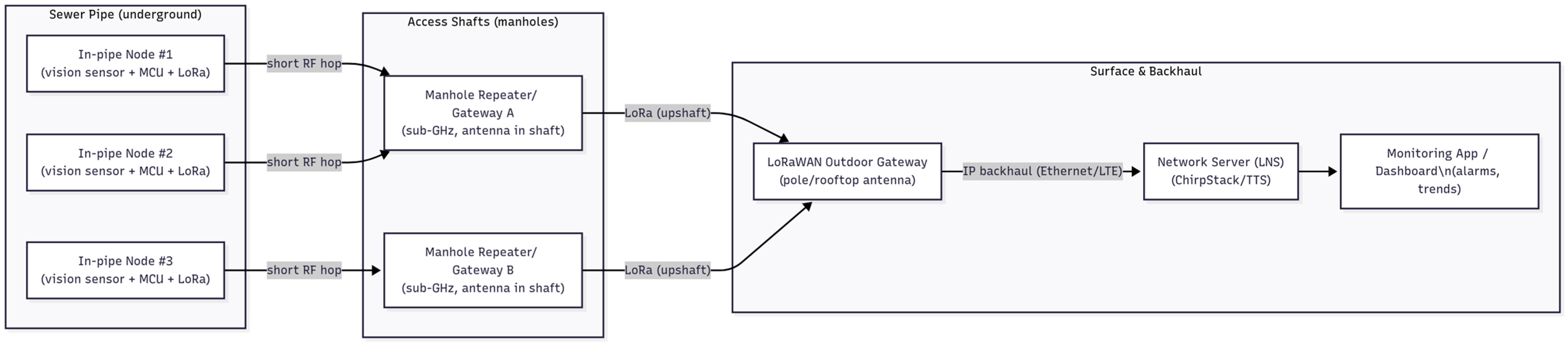

Figure 1 provides an isometric illustration of the proposed system architecture. Each monitoring node consists of a low-power microcontroller with an integrated camera (e.g., a SenseCAP K1101), a LoRa radio module, a lithium battery, and high-intensity LEDs for illumination. The camera captures images of the pipe interior at periodic intervals (e.g., every 30 s or triggered by motion). Images are fed into a TinyML model running on the microcontroller. If the model detects a defect, the device packages the inference result (fault type and confidence) with a timestamp and transmits it via LoRa to a gateway node located above ground. The gateway collects data from multiple devices and forwards it to a cloud service or municipal asset management system for visualization and maintenance scheduling. Between inference cycles, the device enters deep sleep to conserve energy, waking briefly to capture and process new images.

Figure 1.

Proposed system architecture.

An LoRa network can work in sewer pipelines, but only under certain conditions. Signals do not travel well through soil, concrete, and water, so sensors placed deep inside pipes usually cannot talk directly to a surface gateway. The common solution is to install repeaters or gateways in manholes; the in-pipe sensor sends a short LoRa signal to the nearest manhole unit, and that unit forwards the data up to the surface gateway, which then relays it to the cloud or a dashboard. In practice, this means LoRa is reliable for short underground hops (10–50 m) and when manholes are used as communication points, but it does not work well over long stretches of buried pipe without access shafts.

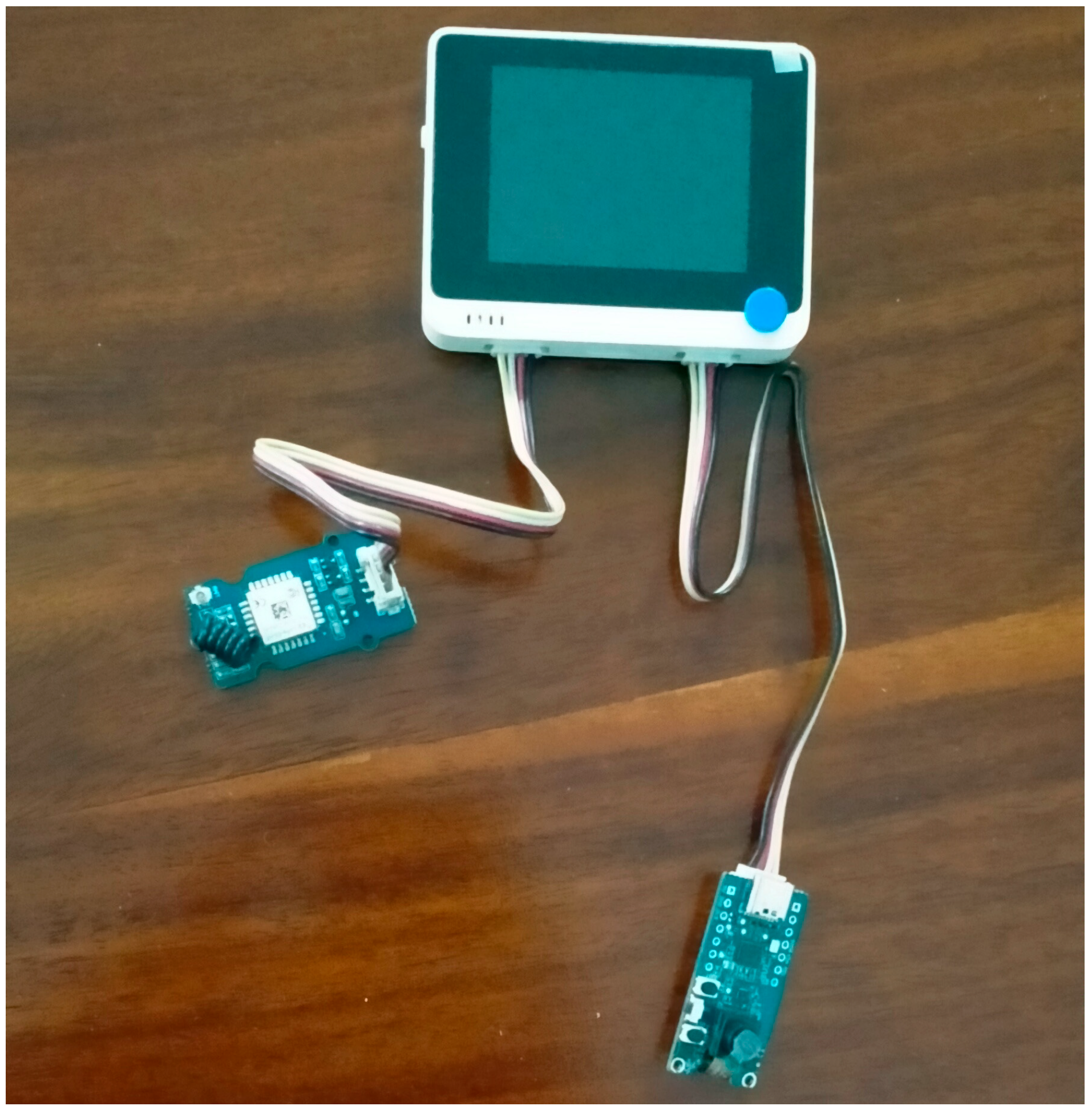

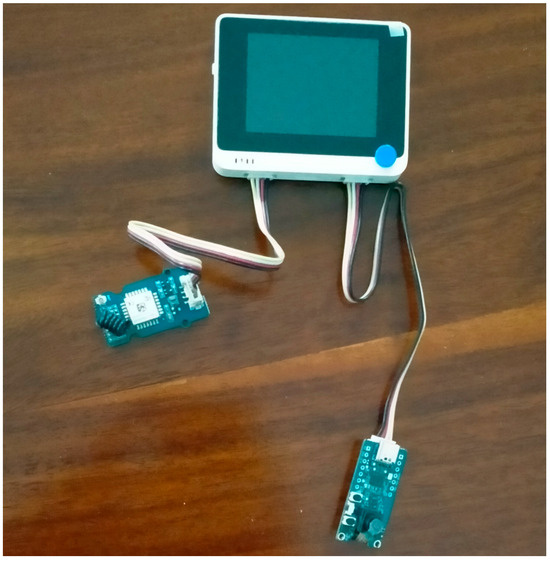

A compact sensor node (SenseCAP K1101), as shown in Figure 2, with an on-board camera and LoRa transceiver, is mounted inside the pipe. The node in the pipe captures images, runs an on-device classifier, and sends defect alerts to a gateway for remote monitoring.

Figure 2.

SenseCAP K1101 (Wio Terminal + Vision AI Sensor + LoRa Module).

The key design considerations for such a system include low power consumption, robust communication, and autonomy:

- Low power: Devices are powered by lithium batteries and must operate for months or years without replacement. The microcontroller uses deep sleep modes, and the TinyML to reduce memory and computational requirements. Only inference results are transmitted, minimizing radio usage.

- Long-range communication: LoRa provides a multi-kilometer range at low data rates, enabling devices to communicate from underground pipelines to surface gateways without relying on cellular or Wi-Fi coverage.

3.2. Dataset Preparation

To develop the classification model, a dataset of sewer pipe images is used and labeled in two key defect classes: utility intrusions and trash blockages. This formulation reflects both practical deployment constraints on embedded hardware and the need to target the most operationally relevant conditions in sewer maintenance.

The dataset was primarily derived from the publicly available Sewer-ML dataset [11], which contains over one million annotated images across a wide range of sewer defects. From this large corpus, we extracted a balanced subset comprising the following:

- A total of 10,000 images of intrusions (Figure 3), where roots or foreign objects penetrate the pipe walls.

Figure 3. Sample images of intrusions.

Figure 3. Sample images of intrusions. - A total of 10,000 images grouped from all other visually observable defect categories. These include debris blockages, cracks, joint offsets, holes, structural buckling, surface deposits, and minor deformations. These are unified under a single “trash” (Figure 4) label to represent obstructive or non-intrusion conditions that still degrade hydraulic capacity or inspection quality.

Figure 4. Sample images of visually observable defect categories.

Figure 4. Sample images of visually observable defect categories. - A total of 10,000 normal (non-defective) images used as a control group for contrastive training.

Each image carried a single label corresponding to one of the three categories (intrusion, trash, or normal). Since the primary deployment target is on-device classification, the final formulation was kept as a multi-class problem, with each input assigned exclusively to one class. The dataset was randomly divided into 60% training, 20% validation, and 20% testing, ensuring balanced representation of both defect types across splits.

3.3. Model Development

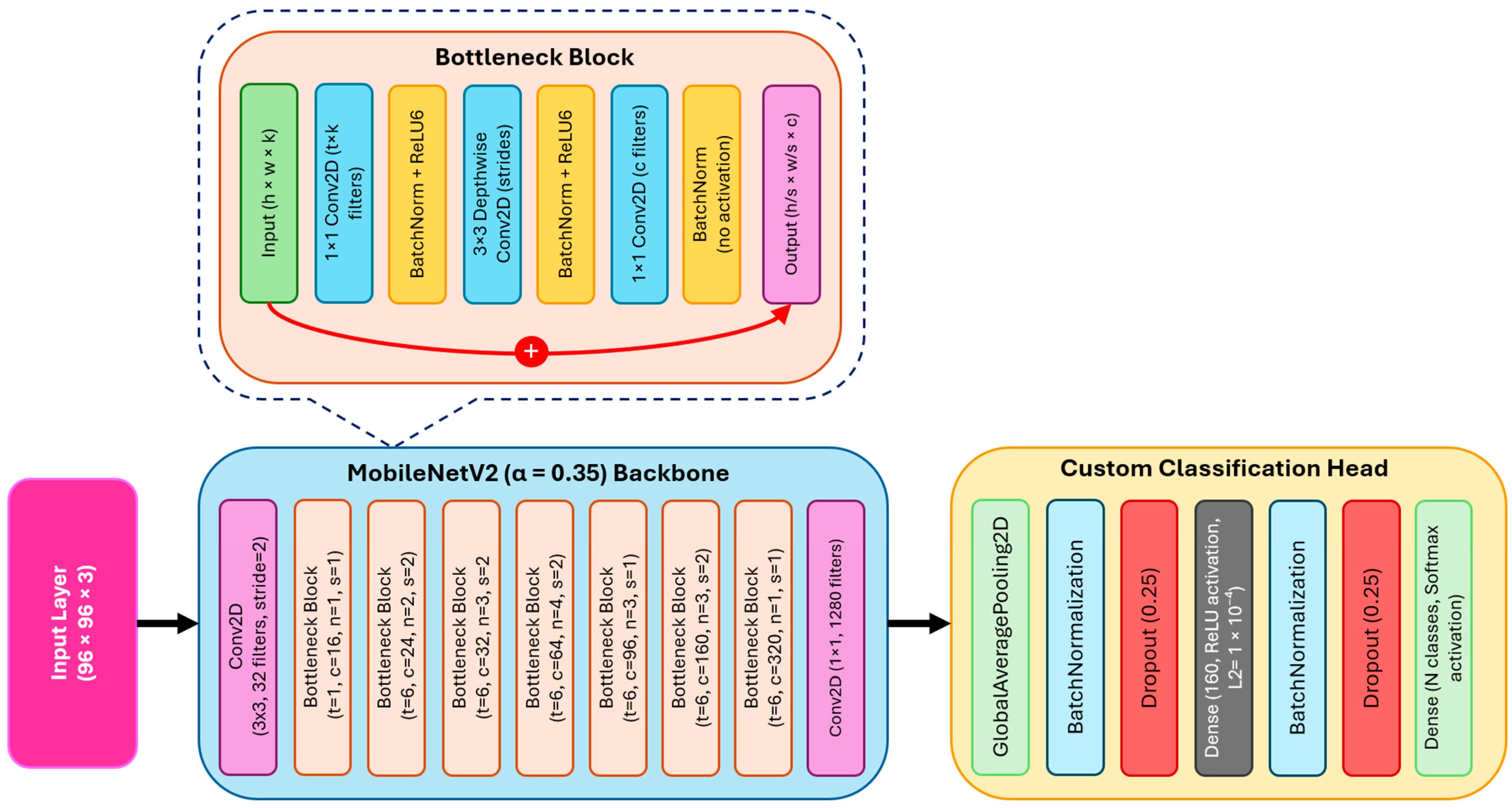

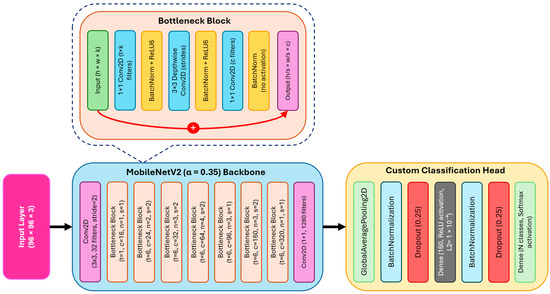

The classification network is based on MobileNetV2 with a reduced width multiplier (α = 0.35) and input resolution of 96 × 96 pixels to keep the model lightweight for embedded deployment. The backbone uses depthwise separable convolutions and inverted residual blocks, which significantly reduce parameter count while retaining representational power. The model architecture is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

TinyML model architecture.

From the truncated base model, we extract intermediate features and pass them through a global average pooling layer. This is followed by batch normalization and dropout (0.25) for regularization. A dense layer with 160 neurons and ReLU activation is added to widen the feature space, also regularized with L2 penalty. After another round of batch normalization and dropout, the network ends with a softmax output layer corresponding to the target classes (intrusion, trash, normal).

This architecture achieves a balance between compact size and sufficient depth, making it suitable for on-device inference on microcontrollers with tight memory and computing budgets.

4. Results and Discussion

The proposed MobileNetV2-based model achieved strong performance on both validation and test datasets. The validation accuracy reached 91.6%, while the test accuracy was 91.4%, demonstrating consistent generalization across unseen data.

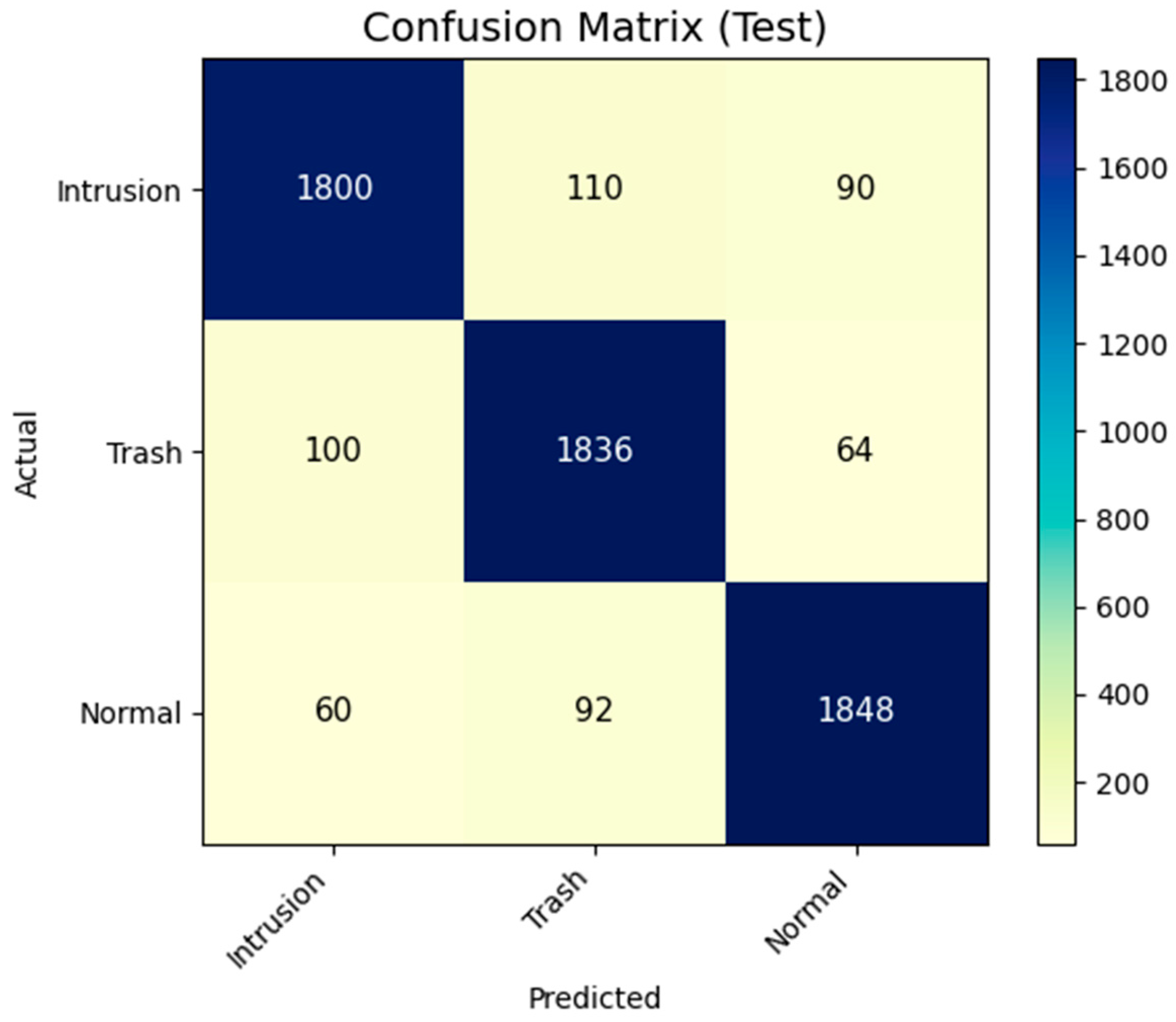

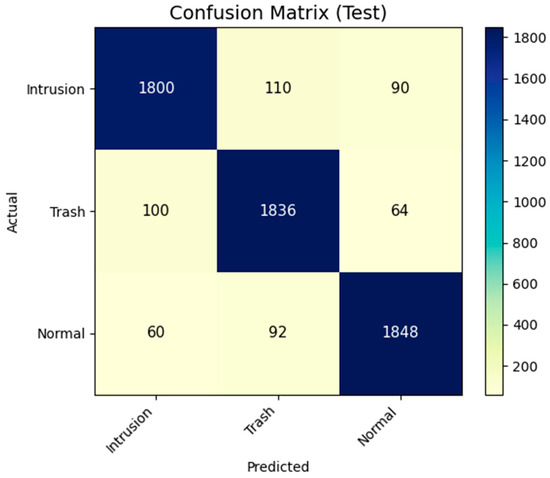

The confusion matrix (Figure 6) summarizes classification outcomes for the three classes (intrusion, trash, normal). Most predictions were correct, with only a small fraction of misclassifications, primarily between intrusion and trash due to overlapping visual features.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix (test dataset).

The test set confusion matrix (Figure 3) highlights both the strengths and remaining challenges of the model. Intrusion was correctly classified in 90.0% of cases, with most errors being misclassified as trash. Trash achieved a 91.8% recall, indicating the model effectively captured diverse visual patterns of blockages and foreign objects, although precision was slightly lower due to occasional confusion with intrusion samples. Normal images achieved the highest recall (92.4%) and precision (92.3%), showing that the model robustly distinguished defect-free sewer conditions. The per-class metrics further validate the balanced performance. The macro-averaged F1-score of 0.914, as shown in Table 1, demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize across all categories, without a strong bias toward any single class. The small differences in precision and recall across intrusion and trash suggest that these two classes share overlapping visual features, such as irregular textures or debris-like patterns.

Table 1.

Classification performance of the defect detection model on the test set.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents a scalable fault detection and condition assessment system for sewer networks based on embedded machine vision and TinyML. The system employs low-power sensor nodes that capture images, run a quantized MobileNetV2 model on a microcontroller, and send defect alerts via LoRa to a gateway. Leveraging transfer learning and data augmentation, the model achieved 91.4% test accuracy on a dataset. By automating sewer inspection and shifting analysis to the edge, the proposed system addresses the limitations of manual CCTV surveys and resource-intensive deep learning pipelines. It enables more frequent inspections, early detection of defects, and proactive maintenance, thereby reducing the risk of catastrophic failures and environmental contamination. The research underscores the importance of curated datasets, energy-efficient models and robust communication for deploying AI in constrained environments.

Future work will expand the model’s ability to detect distinct defect classes and perform instance segmentation. Deployment in real sewer networks will enable us to evaluate long-term performance, battery life, and communication reliability. Ultimately, the integration of embedded machine vision into infrastructure management promises to enhance the sustainability and resilience of urban sewer systems.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset that support the findings is available at [11].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bild, N. TinyML Is Going Down the Drain: TinySewer Is a Low-Power Sewer Faults Detection System. Available online: https://www.edgeimpulse.com/blog/tinyml-is-going-down-the-drain-tinysewer-is-a-low-power-sewer-faults-detection-system (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- YuYussuf, A.N.; Weerasinghe, N.P.; Chen, H.; Hou, L.; Herath, D.; Rashid, M.; Zhang, G.; Setunge, S. Leveraging deep learning techniques for condition assessment of stormwater pipe network. J. Civ. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 15, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.T.; Reiterer, A. Improving Sewer Damage Inspection: Development of a Deep Learning Integration Concept for a Multi-Sensor System. Sensors 2024, 24, 7786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, B.; Schalter, B.; White, L.; Köhler, J. Automatic defect detection in sewer network using deep learning based object detector. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.06219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Shao, Z.; Sun, Q.; Yu, Z. Defect detection and 3d reconstruction of complex urban underground pipeline scenes for sewer robots. Sensors 2024, 24, 7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Blight, A.; Bhardwaj, H.; Shaukat, N.; Han, L.; Richardson, R.; Pickering, A.; Jackson-Mills, G.; Barber, A. TinyML-Based In-Pipe Feature Detection for Miniature Robots. Sensors 2025, 25, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandil, A.; Khanafer, M.; Darwiche, A.; Kassem, R.; Matook, F.; Younis, A.; Badran, H.; Bin-Jassem, M.; Ahmed, O.; Behiry, A.; et al. A Machine-Learning-Based and IoT-Enabled Robot Swarm System for Pipeline Crack Detection. IoT 2024, 5, 951–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, M.; Pincheira, M.; Vecchio, M.; Antonelli, F. An adaptable and unsupervised TinyML anomaly detection system for extreme industrial environments. Sensors 2023, 23, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utepov, Y.; Neftissov, A.; Mkilima, T.; Shakhmov, Z.; Akhazhanov, S.; Kazkeyev, A.; Mukhamejanova, A.T.; Kozhas, A.K. Advancing sanitary surveillance: Innovating a live-feed sewer monitoring framework for effective water level and chamber cover detections. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otero, D.; Mateus, R. Self-Supervised Learning for Identifying Defects in Sewer Footage. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.02140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haurum, J.B.; Moeslund, T.B. Sewer-ML: A multi-label sewer defect classification dataset and benchmark. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13451–13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).