Undiagnosed (Pre)Diabetes as a Prevalent and Important Risk Factor for Recurrent Ischemic Outcomes in ACS Patients Undergoing PCI: Results of a Prospective Multicentre PCI Registry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

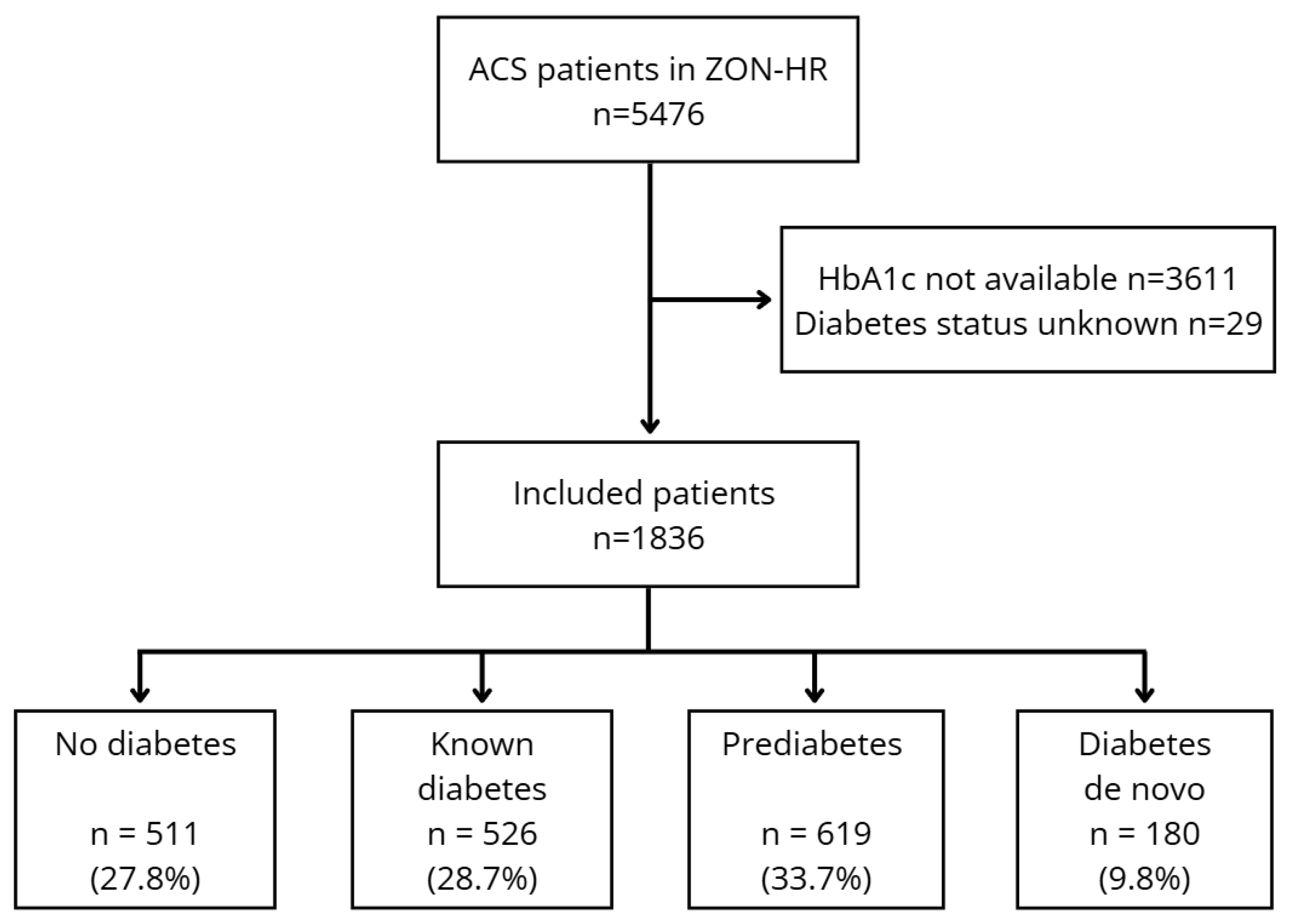

2.1. Study Design and Patient Population

2.2. Endpoints

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

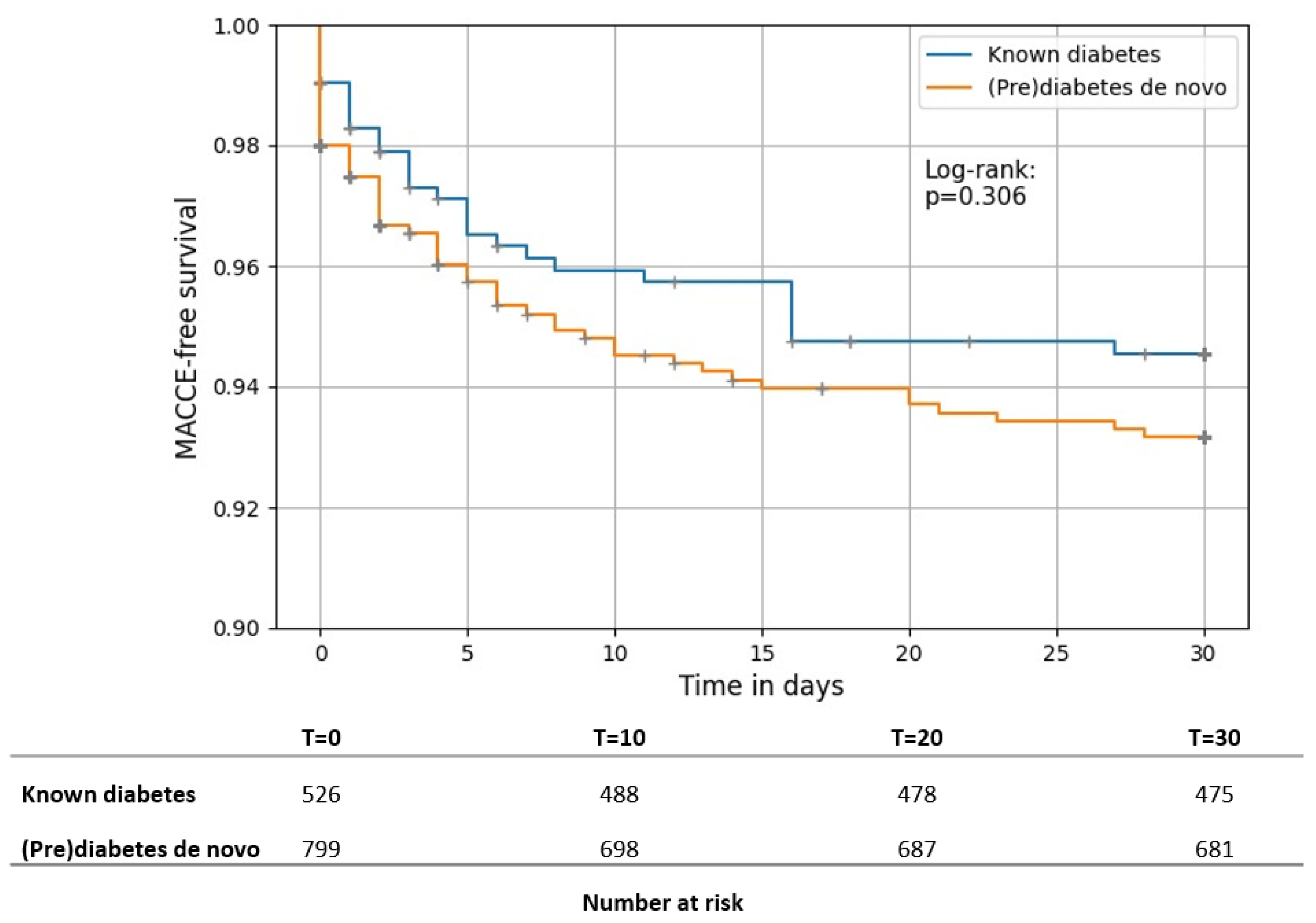

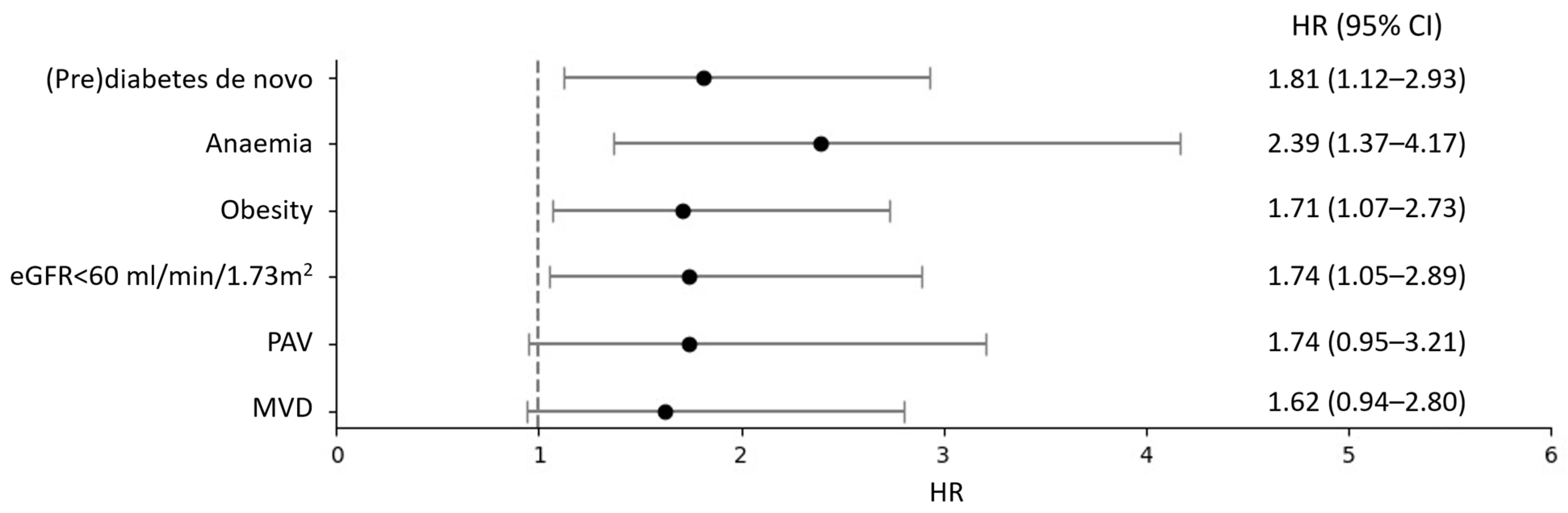

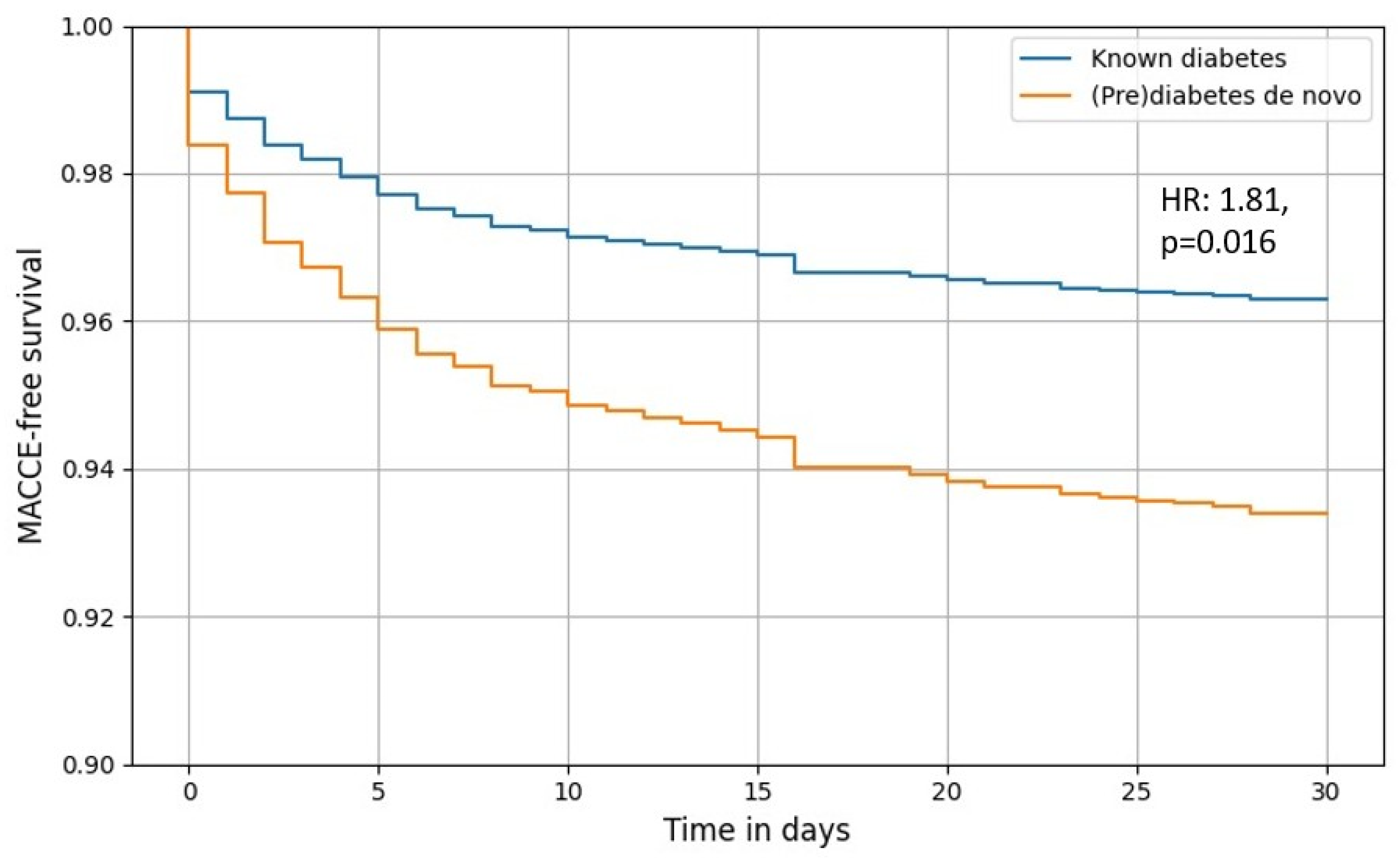

3.2. Primary Outcome

3.3. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | acute coronary syndrome |

| ACE-i | angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor |

| ARB | angiotensin-II receptor blocker |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CABG | coronary artery bypass grafting |

| CI | confidence interval |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| CX | circumflex artery |

| DAPT | dual antiplatelet therapy |

| DAT | dual antithrombotic therapy |

| DPP-4 | dipeptidyl peptidase 4 |

| EASD | European Association for the Study of Diabetes |

| eGFR | estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| ESC | European Society of Cardiology |

| GLP-1 | glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| Hb | haemoglobin |

| HbA1c | haemoglobin A1c |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| iCVA | ischemic cerebrovascular accident |

| LAD | left anterior descending |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein |

| LM | left main |

| MACCE | major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events |

| MACE | major adverse cardiac events |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| MVD | multivessel coronary artery disease |

| NSTEMI | non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

| OHCA | out-of-hospital cardiac arrest |

| PAD | peripheral artery disease |

| PCI | percutaneous coronary intervention |

| PCSK9i | proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor |

| RCA | right coronary artery |

| SGLT2-i | sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors |

| ST | stent thrombosis |

| STEMI | ST-elevation myocardial infarction |

| TAT | triple antithrombotic therapy |

| UAP | unstable angina pectoris |

| ZON-HR | South-East Netherlands Heart Registry |

Appendix A

References

- Marx, N.; Federici, M.; Schütt, K.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Ajjan, R.A.; Antunes, M.J.; Christodorescu, R.M.; Crawford, C.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Eliasson, B.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4043–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babes, E.E.; Bustea, C.; Behl, T.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Nechifor, A.C.; Stoicescu, M.; Brisc, C.M.; Moisi, M.; Gitea, D.; Iovanovici, D.C.; et al. Acute coronary syndromes in diabetic patients, outcome, revascularization, and antithrombotic therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 148, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampouloglou, P.K.; Anastasiou, A.; Bletsa, E.; Lygkoni, S.; Chouzouri, F.; Xenou, M.; Katsarou, O.; Theofilis, P.; Zisimos, K.; Tousoulis, D.; et al. Diabetes Mellitus in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Life 2023, 13, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldez, R.R.; Clare, R.M.; Lopes, R.D.; Dalby, A.J.; Prabhakaran, D.; Brogan, G.X.J.; Giugliano, R.P.; James, S.K.; Tanguay, J.; Pollack, C.V.J.; et al. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus and prediabetes among patients with high-risk non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am. Heart J. 2013, 165, 918–925.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahsan, M.J.; Latif, A.; Ahmad, S.; Willman, C.; Lateef, N.; Shabbir, M.A.; Ahsan, M.Z.; Yousaf, A.; Riasat, M.; Ghali, M.; et al. Outcomes of Prediabetes Compared with Normoglycaemia and Diabetes Mellitus in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Heart Int. 2023, 17, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laichuthai, N.; Abdul-Ghani, M.; Kosiborod, M.; Parksook, W.W.; Kerr, S.J.; DeFronzo, R.A. Newly Discovered Abnormal Glucose Tolerance in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Cardiovascular Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 1958–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rydén, L.; Standl, E.; Bartnik, M.; Van den Berghe, G.; Betteridge, J.; de Boer, M.; Cosentino, F.; Jönsson, B.; Laakso, M.; Malmberg, K.; et al. Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: Executive summary. The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 88–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.U.; Singh, M.; Valavoor, S.; Khan, M.U.; Lone, A.N.; Khan, M.Z.; Khan, M.S.; Mani, P.; Kapadia, S.R.; Michos, E.D.; et al. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Drug-Eluting Stents. Circulation 2020, 142, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrannini, G.; De Bacquer, D.; De Backer, G.; Kotseva, K.; Mellbin, L.; Wood, D.; Rydén, L.; EUROASPIRE V Collaborators. Screening for Glucose Perturbations and Risk Factor Management in Dysglycemic Patients with Coronary Artery Disease-A Persistent Challenge in Need of Substantial Improvement: A Report from ESC EORP EUROASPIRE V. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woelders, E.C.I.; Peeters, D.A.M.; Janssen, S.; Luijkx, J.J.P.; Winkler, P.J.C.; Damman, P.; Remkes, W.S.; van’t Hof, A.W.J.; van Geuns, R.J.M.; ZON-H.R. Investigators. Design and rationale of the South-East Netherlands Heart Registry (ZON-HR). Neth. Heart J. 2025, 33, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanides, R.S.; Kennedy, M.W.; Kedhi, E.; van Dijk, P.R.; Timmer, J.R.; Ottervanger, J.P.; Dambrink, J.; Gosselink, A.M.; Roolvink, V.; Miedema, K.; et al. Impact of elevated HbA1c on long-term mortality in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction in daily clinical practice: Insights from a ‘real world’ prospective registry of the Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2020, 9, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisters, R.; Westra, D.; Putrik, P.; Bosma, H.; Ruwaard, D.; Jansen, M. Regional differences in healthcare costs further explained: The contribution of health, lifestyle, loneliness and mastery. TSG 2022, 100, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care. 2024, 13, 55–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, P.G.; James, S.K.; Atar, D.; Badano, L.P.; Blömstrom-Lundqvist, C.; Borger, M.A.; Di Mario, C.; Dickstein, K.; Ducrocq, G.; Fernandez-Aviles, F.; et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 2569–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffi, M.; Patrono, C.; Collet, J.; Mueller, C.; Valgimigli, M.; Andreotti, F.; Bax, J.J.; Borger, M.A.; Brotons, C.; Chew, D.P.; et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 267–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barents, E.S.E.; Bilo, H.J.G.; Bouma, M.; Dankers, M.; De Rooij, A.; Hart, H.E.; Houweling, S.T.; IJzerman, R.G.; Janssen, P.G.H.; Kerssen, A.; et al. NHG-Standaard Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 (M01) Version 5.5. Available online: https://zorgvoorzuid.nl/media/2022/09/NHG-standaard-DM2-2021-1.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Cosentino, F.; Grant, P.J.; Aboyans, V.; Bailey, C.J.; Ceriello, A.; Delgado, V.; Federici, M.; Filippatos, G.; Grobbee, D.E.; Hansen, T.B.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD: The Task Force for diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 255–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Ramsey, D.; Lee, M.; Mahtta, D.; Khan, M.S.; Nambi, V.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Petersen, L.A.; Walker, A.D.; Kayani, W.T.; et al. Utilization Rates of SGLT2 Inhibitors Among Patients with Type 2 Diabetes, Heart Failure, and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Insights from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JACC Heart Fail. 2023, 11, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnoush, A.H.; Maleki, S.; Arzhangzadeh, A.; Khalaji, A.; Pezeshki, P.S.; Vaziri, Z.; Esmaeili, Z.; Ebrahimi, P.; Ashraf, H.; Masoudkabir, F.; et al. Prediabetes and major adverse cardiac events after acute coronary syndrome: An overestimated concept. Clin. Cardiol. 2024, 47, e24262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, E.; Hsueh, L.; McConeghy, K.W.; Gravenstein, S.; Saade, E. Major adverse cardiovascular event definitions used in observational analysis of administrative databases: A systematic review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lewinski, D.; Kolesnik, E.; Aziz, F.; Benedikt, M.; Tripolt, N.J.; Wallner, M.; Pferschy, P.N.; von Lewinski, F.; Schwegel, N.; Holman, R.R.; et al. Timing of SGLT2i initiation after acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykun, I.; Bayturan, O.; Carlo, J.; Nissen, S.E.; Kapadia, S.R.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Nicholls, S.J.; Puri, R. HbA1c, Coronary atheroma progression and cardiovascular outcomes. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 9, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khiali, S.; Taban-Sadeghi, M.; Sarbakhsh, P.; Khezerlouy-Aghdam, N.; Rezagholizadeh, A.; Asham, H.; Entezari-Maleki, T. SGLT2 Inhibitors’ Cardiovascular Benefits in Individuals Without Diabetes, Heart Failure, and/or Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 63, 1307–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, S.; Erlinge, D.; Storey, R.F.; McGuire, D.K.; de Belder, M.; Eriksson, N.; Andersen, K.; Austin, D.; Arefalk, G.; Carrick, D.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Myocardial Infarction without Diabetes or Heart Failure. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, EVIDoa2300286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael Lincoff, A.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.; Kees Hovingh, G.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prediabetes or Diabetes de Novo (n = 799) | Known Diabetes (n = 526) | % Missing | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67.4 ± 11.2 | 69.5 ± 11.1 | 0 | <0.001 |

| Women (%) | 214 (26.8) | 149 (28.4) | 0 | 0.489 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 ± 4.5 | 29.2 ± 5.3 | 10.5 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 389 (50.5) | 378 (75.0) | 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker (%) | 210 (30.1) | 109 (22.2) | 12.2 | 0.014 |

| Previous stroke (%) | 60 (7.7) | 58 (11.3) | 2.0 | 0.029 |

| Previous MI (%) | 200 (25.4) | 162 (31.6) | 1.8 | 0.015 |

| Previous PCI (%) | 221 (27.8) | 183 (34.9) | 0.6 | 0.005 |

| Previous CABG (%) | 60 (7.6) | 64 (12.2) | 0.7 | 0.005 |

| OHCA (%) | 23 (2.9) | 11 (2.1) | 1.0 | 0.375 |

| MVD (%) | 431 (61.0) | 336 (71.5) | 11.2 | <0.001 |

| PAD (%) | 49 (6.5) | 97 (19.5) | 5.1 | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 46.5 ± 12.3 | 61.4 ± 15.3 | 0 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 75.3 ± 22.9 | 71.6 ± 33.1 | 6.2 | 0.033 |

| Hb (mmol/L) | 8.6 ± 1.1 | 8.3 ± 1.2 | 0.3 | <0.001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.9 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 13.1 | <0.001 |

| Treated vessel | ||||

| LM | 35 (4.4) | 30 (5.7) | 0 | 0.275 |

| LAD | 350 (43.8) | 242 (46.0) | 0 | 0.430 |

| CX | 188 (23.5) | 130 (24.7) | 0 | 0.621 |

| RCA | 304 (38.0) | 173 (32.9) | 0 | 0.056 |

| Other | 41 (5.1) | 45 (8.6) | 0 | 0.013 |

| Multivessel PCI | 97 (12.1) | 79 (15.0) | 0 | 0.131 |

| Prediabetes (n = 557) | Diabetes de Novo (n = 159) | Known Diabetes (n = 490) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAPT/TAT/DAT | 540 (97.0) | 150 (94.3) | 475 (97.0) | 0.174 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid (%) | 492 (88.2) | 136 (85.0) | 406 (82.9) | 0.049 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor (%) | 553 (99.3) | 155 (97.5) | 483 (98.6) | 0.175 |

| Oral anticoagulant (%) | 77 (13.8) | 33 (20.9) | 110 (22.5) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers (%) | 466 (83.7) | 136 (85.5) | 413 (84.3) | 0.846 |

| ACE-i/ARB (%) | 433 (77.7) | 124 (78.0) | 399 (81.4) | 0.310 |

| Statin/ezetimibe/PCSK9i (%) | 539 (96.8) | 150 (94.3) | 463 (94.5) | 0.400 |

| Insulin (%) | 6 (1.1) | 23 (14.7) | 190 (38.9) | <0.001 |

| Metformin (%) | 6 (1.1) | 41 (26.3) | 311 (63.7) | <0.001 |

| SGLT2-i (%) | 33 (5.9) | 32 (20.1) | 122 (24.9) | <0.001 |

| No glucose-mediating medication (%) | 499 (92.2) | 92 (59.0) | 76 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Prediabetes (n = 253) | Diabetes de Novo (n = 96) | Known Diabetes (n = 301) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insulin (%) | 0 (0) | 11 (11.5) | 116 (38.5) | <0.001 |

| Metformin (%) | 3 (1.2) | 36 (37.5) | 179 (59.5) | <0.001 |

| SGLT2-i (%) | 22 (8.7) | 17 (17.7) | 72 (23.9) | <0.001 |

| No glucose-mediating medication (%) | 288 (90.1) | 51 (53.1) | 48 (15.9) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Janssen, S.; Woelders, E.C.I.; Peeters, D.A.M.; Winkler, P.J.C.; Damman, P.; Remkes, W.S.; Luijkx, J.J.P.; Merry, A.H.H.; Rasoul, S.; van Geuns, R.J.M.; et al. Undiagnosed (Pre)Diabetes as a Prevalent and Important Risk Factor for Recurrent Ischemic Outcomes in ACS Patients Undergoing PCI: Results of a Prospective Multicentre PCI Registry. Diabetology 2026, 7, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020025

Janssen S, Woelders ECI, Peeters DAM, Winkler PJC, Damman P, Remkes WS, Luijkx JJP, Merry AHH, Rasoul S, van Geuns RJM, et al. Undiagnosed (Pre)Diabetes as a Prevalent and Important Risk Factor for Recurrent Ischemic Outcomes in ACS Patients Undergoing PCI: Results of a Prospective Multicentre PCI Registry. Diabetology. 2026; 7(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanssen, Sanne, Eva C. I. Woelders, Denise A. M. Peeters, Patty J. C. Winkler, Peter Damman, Wouter S. Remkes, Jasper J. P. Luijkx, Audrey H. H. Merry, Saman Rasoul, Robert Jan M. van Geuns, and et al. 2026. "Undiagnosed (Pre)Diabetes as a Prevalent and Important Risk Factor for Recurrent Ischemic Outcomes in ACS Patients Undergoing PCI: Results of a Prospective Multicentre PCI Registry" Diabetology 7, no. 2: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020025

APA StyleJanssen, S., Woelders, E. C. I., Peeters, D. A. M., Winkler, P. J. C., Damman, P., Remkes, W. S., Luijkx, J. J. P., Merry, A. H. H., Rasoul, S., van Geuns, R. J. M., & van ’t Hof, A. W. J., on behalf of the ZON-HR Investigators. (2026). Undiagnosed (Pre)Diabetes as a Prevalent and Important Risk Factor for Recurrent Ischemic Outcomes in ACS Patients Undergoing PCI: Results of a Prospective Multicentre PCI Registry. Diabetology, 7(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology7020025