Availability and Affordability of Medicines for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease across Countries: Information Learned from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Availability and Affordability of Essential Medicines for Diabetes

3. Availability and Affordability of Antihypertensives

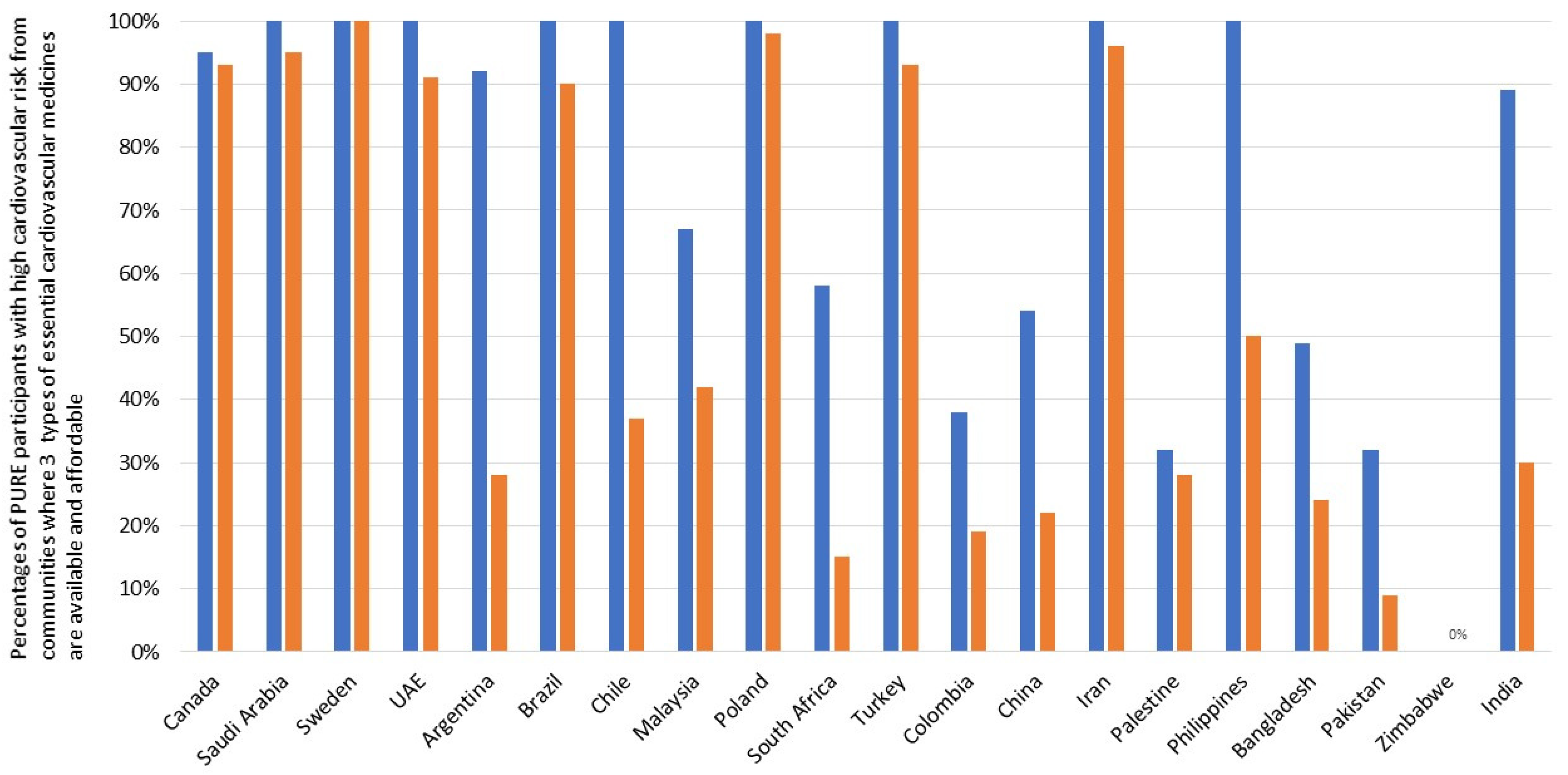

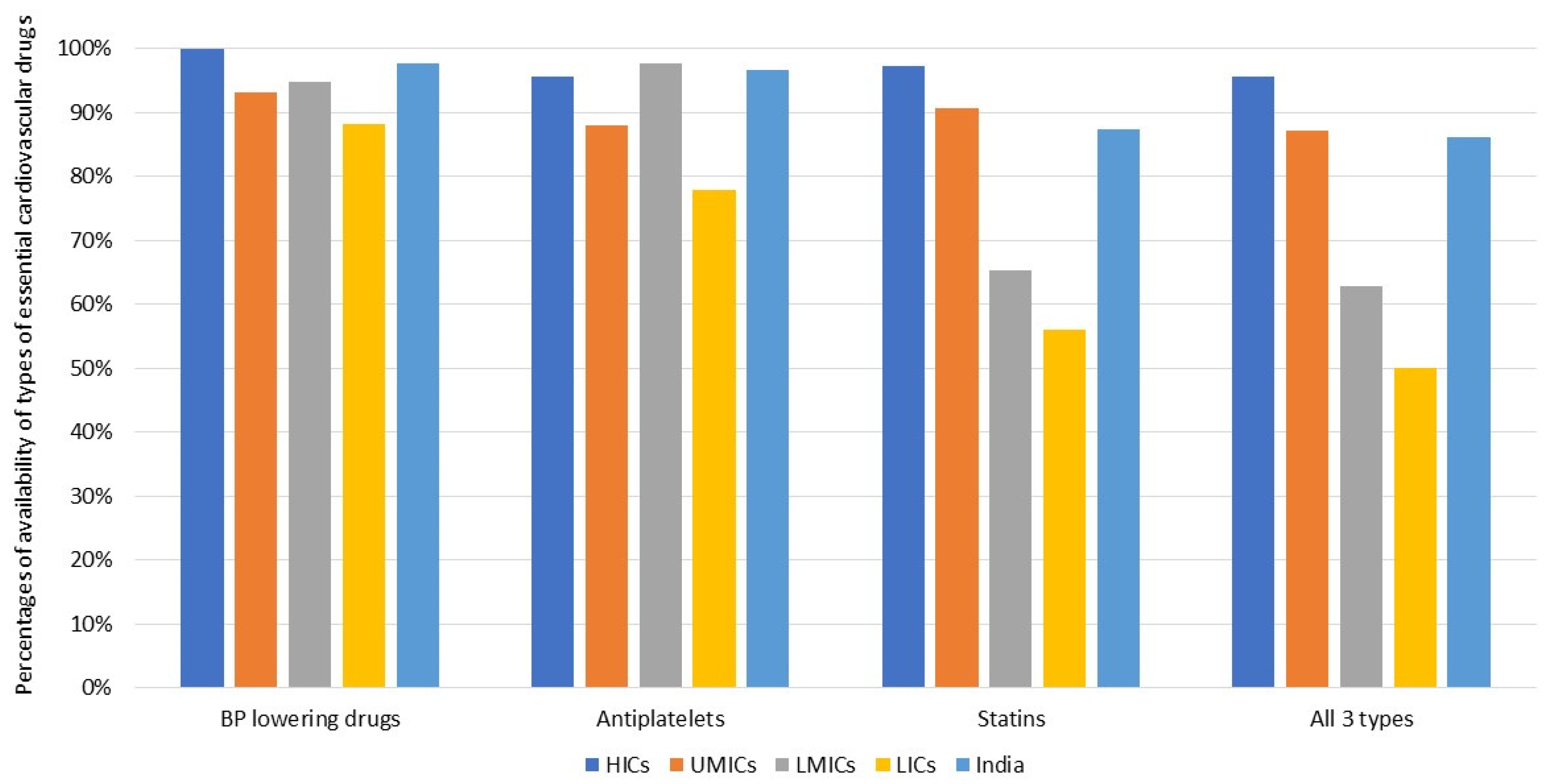

4. The Availability and Affordability of Essential Cardiovascular Medicines (for CVD Secondary Prevention)

5. Availability and Affordability of Essential Cardiovascular Medicines and Cardiovascular Outcomes

6. Availability, Affordability, and Consumption of Fruits and Vegetables

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X.; Song, X.; Ren, Y.; Shan, P.F. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Ohlrogge, A.W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 138, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/ (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- World Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines—22nd List. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2021.02 (accessed on 9 November 2021).

- van Mourik, M.S.; Cameron, A.; Ewen, M.; Laing, R.O. Availability, price and affordability of cardiovascular medicines: A comparison across 36 countries using WHO/HAI data. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2010, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geldsetzer, P.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Marcus, M.-E.; Ebert, C.; Zhumadilov, Z.; Wesseh, C.S.; Tsabedze, L.; Supiyev, A.; Sturua, L.; Bahendeka, S.K.; et al. The state of hypertension care in 44 low-income and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional study of nationally representative individual-level data from 11 million adults. Lancet 2019, 394, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Husain, M.J.; Datta, B.; Kostova, D.; Joseph, K.T.; Asma, S.; Richter, P.; Jaffe, M.G.; Kishore, S.P. Access to Cardiovascular Disease and Hypertension Medicines in Developing Countries: An Analysis of Essential Medicine Lists, Price, Availability, and Affordability. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2020, 9, e015302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walli-Attaei, M.; Joseph, P.; Rosengren, A.; Chow, C.K.; Rangarajan, S.; A Lear, S.; AlHabib, K.F.; Davletov, K.; Dans, A.; Lanas, F.; et al. Variations between women and men in risk factors, treatments, cardiovascular disease incidence, and death in 27 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (PURE): A prospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 396, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, K.; Chow, C.K.; Vaz, M.; Rangarajan, S.; Yusufali, A. The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study: Examining the impact of societal influences on chronic noncommunicable diseases in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Am. Hear. J. 2009, 158, 1–7.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, S.; Rangarajan, S.; Teo, K.; Islam, S.; Li, W.; Liu, L.; Bo, J.; Lou, Q.; Lu, F.; Liu, T.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk and Events in 17 Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.K.; Lock, K.; Madhavan, M.; Corsi, D.J.; Gilmore, A.B.; Subramanian, S.V.; Li, W.; Swaminathan, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Avezum, A.; et al. Environmental Profile of a Community’s Health (EPOCH): An instrument to measure environmental determinants of cardiovascular health in five countries. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e14294. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, S.; Islam, S.; Chow, C.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Dagenais, G.; Diaz, R.; Gupta, R.; Kelishadi, R.; Iqbal, R.; Avezum, A.; et al. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): A prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet 2011, 378, 1231–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chow, C.K.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Hu, W.; Alhabib, K.; Avezum, A.; Cheng, X.; Chifamba, J.; Dagenais, G.; Dans, A.; Egbujie, B.A.; et al. Availability and affordability of essential medicines for diabetes across high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: A prospective epidemiological study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaei, M.W.; Khatib, R.; McKee, M.; Lear, S.; Dagenais, G.; Igumbor, E.; Alhabib, K.; Kaur, M.; Kruger, L.; Teo, K.; et al. Availability and affordability of blood pressure-lowering medicines and the effect on blood pressure control in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: An analysis of the PURE study data. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e411–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khatib, R.; McKee, M.; Shannon, H.; Chow, C.; Rangarajan, S.; Teo, K.; Wei, L.; Mony, P.; Mohan, V.; Gupta, R.; et al. Availability and affordability of cardiovascular disease medicines and their effect on use in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: An analysis of the PURE study data. Lancet 2016, 387, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niens, L.; Van De Poel, E.; Cameron, A.; Ewen, M.; Laing, R.; Brouwer, W. Practical measurement of affordability: An application to medicines. Bull. World Health Organ. 2012, 90, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dagenais, G.R.; Gerstein, H.C.; Zhang, X.; McQueen, M.; Lear, S.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Mohan, V.; Mony, P.; Gupta, R.; Kutty, V.R.; et al. Variations in Diabetes Prevalence in Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries: Results From the Prospective Urban and Rural Epidemiological Study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 780–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chow, C.K.; Teo, K.K.; Rangarajan, S.; Islam, S.; Gupta, R.; Avezum, A.; Bahonar, A.; Chifamba, J.; Dagenais, G.; Diaz, R.; et al. Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control of Hypertension in Rural and Urban Communities in High-, Middle-, and Low-Income Countries. JAMA 2013, 310, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chow, C.K.; Meng, Q. Polypills for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.K.; Nguyen, T.N.; Marschner, S.; Diaz, R.; Rahman, O.; Avezum, A.; Lear, S.A.; Teo, K.; E Yeates, K.; Lanas, F.; et al. Availability and affordability of medicines and cardiovascular outcomes in 21 high-income, middle-income and low-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2020, 5, e002640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, C.; Uauy, R.; Kumanyika, S.; Shetty, P. The Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: Process, product and policy implications. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, V.; Yusuf, S.; Chow, C.K.; Dehghan, M.; Corsi, D.J.; Lock, K.; Popkin, B.; Rangarajan, S.; Khatib, R.; Lear, S.A.; et al. Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: Findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e695–e703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cameron, A.; Ewen, M.; Ross-Degnan, D.; Ball, D.; Laing, R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: A secondary analysis. Lancet 2009, 373, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewen, M.; Zweekhorst, M.; Regeer, B.; Laing, R. Baseline assessment of WHO’s target for both availability and affordability of essential medicines to treat non-communicable diseases. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendis, S.; Fukino, K.; Cameron, A.; Laing, R.; Filipe, A., Jr.; Khatib, O.; Leowski, J.; Ewen, M. The availability and affordability of selected essential medicines for chronic diseases in six low- and middle-income countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2007, 85, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, V.J.; Kaplan, W.; Kwan, G.; Laing, R.O. Access to Medications for Cardiovascular Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Circulation 2016, 133, 2076–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, X.; Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Mossialos, E.; Mensah, G.A.; Masoudi, F.A.; Lu, J.; Li, X.; et al. Availability, cost, and prescription patterns of antihypertensive medications in primary health care in China: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2017, 390, 2559–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Satheesh, G.; Sharma, A.; Puthean, S.; Muhammed, A.T.P.; Jereena, E.; Mishra, S.R.; Unnikrishnan, M.K. Availability, price and affordability of essential medicines for managing cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: A statewide survey in Kerala, India. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2020, 25, 1467–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, C.K.; Thakkar, J.; Bennett, A.; Hillis, G.; Burke, M.; Usherwood, T.; Vo, K.; Rogers, K.; Atkins, E.; Webster, R.; et al. Quarter-dose quadruple combination therapy for initial treatment of hypertension: Placebo-controlled, crossover, randomised trial and systematic review. Lancet 2017, 389, 1035–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Vanegas, E.P.; Rovira, J.; Godman, B.; Bochenek, T. Medicine Shortages: Gaps Between Countries and Global Perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwalm, J.-D.; McCready, T.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Yusoff, K.; Attaran, A.; Lamelas, P.; Camacho, P.A.; Majid, F.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Thabane, L.; et al. A community-based comprehensive intervention to reduce cardiovascular risk in hypertension (HOPE 4): A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.N.; Yusuf, S.; Chow, C.K. Availability and Affordability of Medicines for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease across Countries: Information Learned from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological Study. Diabetology 2022, 3, 236-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology3010014

Nguyen TN, Yusuf S, Chow CK. Availability and Affordability of Medicines for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease across Countries: Information Learned from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological Study. Diabetology. 2022; 3(1):236-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology3010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Tu Ngoc, Salim Yusuf, and Clara Kayei Chow. 2022. "Availability and Affordability of Medicines for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease across Countries: Information Learned from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological Study" Diabetology 3, no. 1: 236-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology3010014

APA StyleNguyen, T. N., Yusuf, S., & Chow, C. K. (2022). Availability and Affordability of Medicines for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease across Countries: Information Learned from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological Study. Diabetology, 3(1), 236-245. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology3010014