Patterns and Outcomes of Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD) in Oman: A Retrospective Study in a Culturally Conservative Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

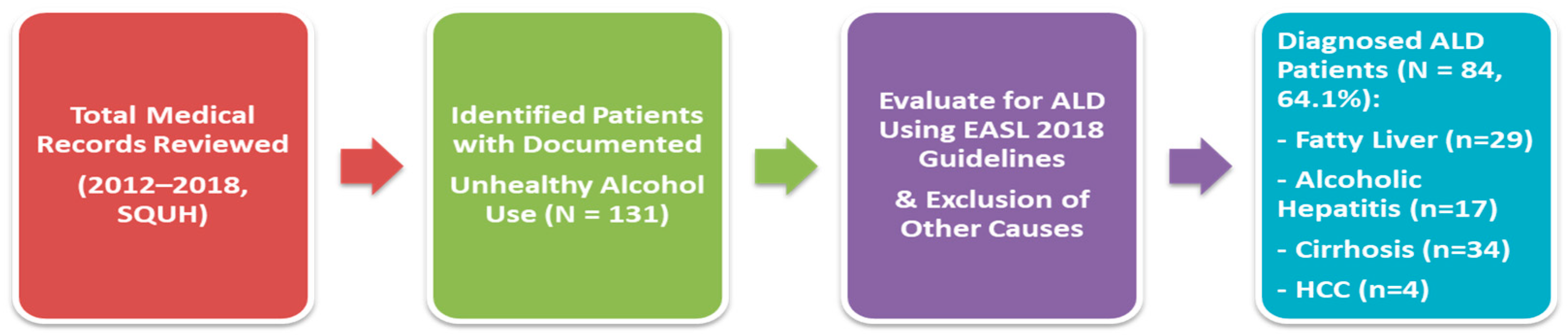

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patient Selection and Definitions

2.3. Data Collection

- Demographic information: age, sex, nationality, and known comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, viral hepatitis, and metabolic syndrome).

- Alcohol history: pattern, frequency, and duration of alcohol consumption based on available clinical notes and social history.

- Clinical presentation at index admission: symptoms such as jaundice, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, and signs of decompensated liver disease.

- Laboratory parameters: liver function tests (AST, ALT, total and direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase), coagulation profile (INR), renal function (creatinine, urea), serum albumin, complete blood count, and markers of synthetic liver function.

- Radiological findings: abdominal ultrasound and/or CT imaging reports were reviewed to assess for hepatomegaly, liver echotexture, splenomegaly, ascites, and portosystemic collaterals.

- Portal hypertension: this was defined using a combination of clinical, laboratory, imaging, and endoscopic criteria; these included the presence of splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150,000/μL), ascites, or portosystemic collaterals detected on imaging (ultrasound or CT), as well as esophageal or gastric varices documented via upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

- Mortality data: these were retrieved from hospital records and follow-up visits, including the date and cause of death when available.

2.4. Complication Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and ALD Manifestations

3.2. Clinical Presentation Across ALD Stages

3.3. Complications in ALD Patients: Initial Presentation and Overall Course

3.4. Mortality and Health Status

3.5. Causes of Death

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Childers, R.E.; Ahn, J. Diagnosis of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Key Foundations and New Developments. Clin. Liver Dis. 2016, 20, 457–471. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27373609/ (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.K.; Kodali, S.; Vucovich, L.A.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Schiano, T.D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Systematic Review. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 40, 1390–1402. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27254289/ (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Levitsky, J.; Mailliard, M.E. Diagnosis and therapy of alcoholic liver disease. Semin. Liver Dis. 2004, 24, 233–247. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15349802/ (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Van Ness, M.M.; Diehl, A.M. Is liver biopsy useful in the evaluation of patients with chronically elevated liver enzymes? Ann. Intern. Med. 1989, 111, 473–478. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2774372 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Phillips, M. The Alcohol Drinking History. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK418 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Mathurin, P.; Lucey, M.R. Management of alcoholic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2012, 56 (Suppl. 1), S39–S45. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22300464 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.P.; Vittinghoff, E.; Dodge, J.L.; Cullaro, G.; Terrault, N.A. National Trends and Long-term Outcomes of Liver Transplant for Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease in the United States. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 340–348. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/national-trends-and-long-term-outcomes-of-liver-transplant-3b4wkkokdh (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cholankeril, G.; Gadiparthi, C.; Yoo, E.R.; Dennis, B.B.; Li, A.A.; Hu, M.; Wong, K.; Kim, D.; Ahmed, A. Temporal Trends Associated With the Rise in Alcoholic Liver Disease-related Liver Transplantation in the United States. Transplantation 2019, 103, 131–139. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/temporal-trends-associated-with-the-rise-in-alcoholic-liver-24buh4vqgy (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Al Shabeeb, R.; Eberly, K.E.; Shah, D.; Nguyen, V.; Ong, J.; Henry, L.; Alqahtani, S.A. The changing epidemiology of adult liver transplantation in the United States in 2013–2022: The dominance of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 8, e0352. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/the-changing-epidemiology-of-adult-liver-transplantation-in-4msuc0oc04 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Åberg, F.; Jiang, Z.G.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Männistö, V. Alcohol-associated liver disease—global epidemiology. Hepatology 2024, 80, 1307–1322. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/alcohol-associated-liver-disease-global-epidemiology-508cb1ao8b (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kling, C.E.; Perkins, J.D.; Carithers, R.L.; Donovan, D.M.; Sibulesky, L. Recent trends in liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease in the United States. World J. Hepatol. 2017, 9, 1315–1321. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/recent-trends-in-liver-transplantation-for-alcoholic-liver-22vxf3xzud (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureddin, N.; Yang, J.D.; Alkhouri, N.; Noreen, S.M.; Toll, A.E.; Todo, T.; Ayoub, W.; Kuo, A.; Voidonikolas, G.; Kotler, H.G.; et al. Increase in Alcoholic Hepatitis as an Etiology for Liver Transplantation in the United States: A 2004–2018 Analysis. Transplant. Direct 2020, 6, e612. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/increase-in-alcoholic-hepatitis-as-an-etiology-for-liver-1odt1fe3n7 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Díaz, L.A.; Suparan, K.; Tothanarungroj, P.; Sirimangklanurak, S.; Auttapracha, T.; Blaney, H.L.; Sukphutanan, B.; Pang, Y.; Kongarin, S.; et al. Global Epidemiology of Alcohol-Related Liver Disease, Liver Cancer, and Alcohol Use Disorder, 2000–2021. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, 525–547. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/global-epidemiology-of-alcohol-related-liver-disease-liver-41zy17gc5owb (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazo, M.; Mitchell, M.C. Epidemiology and risk factors for alcoholic liver disease. In Alcoholic and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Bench to Bedside [Internet]; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–20. Available online: https://pure.johnshopkins.edu/en/publications/epidemiology-and-risk-factors-for-alcoholic-liver-disease (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Al Ta’ani, O.; Aleyadeh, W.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Alnimer, L.; Ismail, A.; Natour, B.; Njei, B. The burden of cirrhosis and other chronic liver disease in the middle east and North Africa (MENA) region over three decades. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2979. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/the-burden-of-cirrhosis-and-other-chronic-liver-disease-in-710vdzd1hqjl (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chacko, K.R.; Reinus, J. Spectrum of Alcoholic Liver Disease. Clin. Liver Dis. 2016, 20, 419–427. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27373606 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thursz, M.; Gual, A.; Lackner, C.; Mathurin, P.; Moreno, C.; Spahr, L.; Sterneck, M.; Cortez-Pinto, H. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of alcohol-related liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 154–181. Available online: http://www.journal-of-hepatology.eu/article/S0168827818302149/fulltext (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- AlMarri, T.S.K.; Oei, T.P.S. Alcohol and substance use in the Arabian Gulf region: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2009, 44, 222–233. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/alcohol-and-substance-use-in-the-arabian-gulf-region-a-5ehany6j76 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rostam-Abadi, Y.; Gholami, J.; Shadloo, B.; Mohammad Aghaei, A.; Mardaneh Jobehdar, M.; Ardeshir, M.; Sangchooli, A.; Amin-Esmaeili, M.; Taj, M.; Saeed, K.; et al. Alcohol use, alcohol use disorder and heavy episodic drinking in the Eastern Mediterranean region: A systematic review. Addiction 2024, 119, 984–997. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/alcohol-use-alcohol-use-disorder-and-heavy-episodic-drinking-3u03fw5eet (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaidan, Z.A.J.; Dorvlo, A.S.S.; Viernes, N.; Al-Suleimani, A.; Al-Adawi, S. Hazardous and Harmful Alcohol Consumption Among Non-Psychotic Psychiatric Clinic Attendees in Oman. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2007, 5, 3–15. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/hazardous-and-harmful-alcohol-consumption-among-non-2tcodx4a8v (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Wang, F.; Wong, N.K.; Lv, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, J.; Chen, S.; Li, W.; Koike, K.; Liu, X.; et al. Epidemiological Realities of Alcoholic Liver Disease: Global Burden, Research Trends, and Therapeutic Promise. Gene Expr. 2020, 20, 105–118. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/epidemiological-realities-of-alcoholic-liver-disease-global-254mpwfl7o (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Xiao, P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Gao, Y. Curbing alcohol-associated liver disease by increasing alcohol excise taxes. Chin. Med. J. 2024, 137, 2412. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11479448 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Arab, J.P.; Dunn, W.; Im, G.; Singal, A.K. Changing landscape of alcohol-associated liver disease in younger individuals, women, and ethnic minorities. Liver Int. 2024, 44, 1537–1547. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/changing-landscape-of-alcohol-associated-liver-disease-in-1unqcuyuvb (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Narro, G.E.C.; Díaz, L.A.; Ortega, E.K.; Garín, M.F.B.; Reyes, E.C.; Delfin, P.S.M.; Arab, J.P.; Bataller, R. Alcohol-Related liver disease: A global perspective. Ann. Hepatol. 2024, 29, 101499. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/alcohol-related-liver-disease-a-global-perspective-5fi125h67q (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Amonker, S.; Houshmand, A.; Hinkson, A.; Rowe, I.; Parker, R. Prevalence of alcohol-associated liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatol. Commun. 2023, 7, e0133. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/prevalence-of-alcohol-associated-liver-disease-a-systematic-q1lebzp9 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waghmare, G.R.; Katekar, V.A.; Deshmukh, S.P. A review: Alcoholic liver disease pathophysiology, current molecular and clinical perspectives. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 25, 014–024. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/a-review-alcoholic-liver-disease-pathophysiology-current-2txwgabyu1 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Noori, M.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Collins, G.S.; Kaufman, J.S.; Kolahi, A.-A. Burden of diseases and injuries attributable to alcohol consumption in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990–2019. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19301. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36369336 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Abbas, D.; Ciricillo, J.A.; Elom, H.A.; Moon, A.M. Extrahepatic Health Effects of Alcohol Use and Alcohol-associated Liver Disease. Clin. Ther. 2023, 45, 1201–1211. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0149291823003223 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Al Kaabi, H.; Al Alawi, A.M.; Al Falahi, Z.; Al-Naamani, Z.; Al Busafi, S.A. Clinical Characteristics, Etiology, and Prognostic Scores in Patients with Acute Decompensated Liver Cirrhosis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5756. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/clinical-characteristics-etiology-and-prognostic-scores-in-2lw5s4q2ey (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ghavimi, S.; Azimi, H.; Patel, N.; Shulik, O. Geriatric Hepatology: The Hepatic Diseases of the Elderly and Liver. J. Dig. Dis. Hepatol. 2019, 3, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Smadi, K.; Qureshi, A.; Buitrago, M.; Ashouri, B.; Kayali, Z. Survival and Disease Progression in Older Adult Patients With Cirrhosis: A Retrospective Study. Int. J. Hepatol. 2024, 2024, 5852680. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/survival-and-disease-progression-in-older-adult-patients-6v94kdthy1lu (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, E.; Torres, S.; Liu, B.; Baden, R.; Bhuket, T.; Wong, R.J. High Prevalence of Cirrhosis at Initial Presentation Among Safety-Net Adults with Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2017, 8, 235–240. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/high-prevalence-of-cirrhosis-at-initial-presentation-among-28l430wzeq (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Papić, N.; Radmanić, L.; Dušek, D.; Kurelac, I.; Lepej, S.Z.; Vince, A. Trends of Late Presentation to Care in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C during a 10-Year Period in Croatia. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2020, 12, 74–81. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/trends-of-late-presentation-to-care-in-patients-with-chronic-2dypt0lvaj (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Toyoda, H. Low surveillance receipt in cirrhotic patients with cured HCV: Where are the barriers? Liver Int. 2023, 43, 962–963. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/low-surveillance-receipt-in-cirrhotic-patients-with-cured-33xecxs5 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütte, K.; Bornschein, J.; Kahl, S.; Seidensticker, R.; Arend, J.; Ricke, J.; Malfertheiner, P. Delayed Diagnosis of HCC with Chronic Alcoholic Liver Disease. Liver Cancer 2012, 1, 257–266. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/delayed-diagnosis-of-hcc-with-chronic-alcoholic-liver-3njz3vd7l3 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Doshi, S.D.; Stotts, M.J.; Hubbard, R.A.; Goldberg, D.S. The Changing Burden of Alcoholic Hepatitis: Rising Incidence and Associations with Age, Gender, Race, and Geography. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 1707–1714. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/the-changing-burden-of-alcoholic-hepatitis-rising-incidence-3ajnt2x21w (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Otete, H.E.; Orton, E.; West, J.; Fleming, K.M. Sex and age differences in the early identification and treatment of alcohol use: A population-based study of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Addiction 2015, 110, 1932–1940. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/sex-and-age-differences-in-the-early-identification-and-vyu4qkpkf6 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Rong, Y.; Zang, H.; Liu, W.; You, S.; Xin, S. Clinical characteristics of 4132 patients with alcoholic liver disease. Chin. J. Hepatol. 2015, 23, 680–683. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/clinical-characteristics-of-4132-patients-with-alcoholic-1flgul4uu2 (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Shimizu, I.; Kamochi, M.; Yoshikawa, H.; Nakayama, Y. Gender Difference in Alcoholic Liver Disease. In Trends in Alcoholic Liver Disease Research—Clinical and Scientific Aspects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/gender-difference-in-alcoholic-liver-disease-3ussghfiab (accessed on 6 April 2025).

- Bizzaro, D.; Becchetti, C.; Trapani, S.; Lavezzo, B.; Zanetto, A.; D’Arcangelo, F.; Merli, M.; Lapenna, L.; Invernizzi, F.; Taliani, G.; et al. Influence of sex in alcohol-related liver disease: Pre-clinical and clinical settings. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2023, 11, 218–227. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/influence-of-sex-in-alcohol-related-liver-disease-pre-2ia9j1eh (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Anouti, A.; Mellinger, J.L. The Changing Epidemiology of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: Gender, Race, and Risk Factors. Semin. Liver Dis. 2022, 43, 050–059. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/the-changing-epidemiology-of-alcohol-associated-liver-nf6kdja3 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, L.M.; Likhitsup, A.; Winder, G.S.; Saeed, N.; Hassan, A.; Sonnenday, C.J.; Fontana, R.J.; Mellinger, J. Gender Disparities in Patients With Alcoholic Liver Disease Evaluated for Liver Transplantation. Transplantation 2020, 104, 293–298. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/gender-disparities-in-patients-with-alcoholic-liver-disease-1npsyeiig5 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mirowski, K.; Balicka-Ślusarczyk, B.; Hydzik, P.; Zwolińska-Wcisło, M. Alcohol-associated liver disease—A current overview. Folia Med. Cracov. 2024, 64, 93–104. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/alcohol-associated-liver-disease-a-current-overview-5zz88cxy6qxs (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parate, T.; Chavan, P.; Parate, R. A Clinical Study of Spectrum of Liver Diseases in Alcoholic with Respect to Predictors of Severity and Prognosis. Vidarbha J. Intern. Med. 2022, 32, 100–107. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/a-clinical-study-of-spectrum-of-liver-diseases-in-alcoholic-of1exrvi (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tapper, E.B.; Parikh, N.D.; Liangpunsakul, S. Attacking Alcohol-Related Liver Disease by Taxing Alcohol Sales. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 45, 51–53. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/attacking-alcohol-related-liver-disease-by-taxing-alcohol-j2xfdkfhvn (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- El-Menyar, A.; Consunji, R.; Mekkodathil, A.; Peralta, R.; Al-Thani, H. Alcohol Screening in a National Referral Hospital: An Observational Study from Qatar. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 6082–6088. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/alcohol-screening-in-a-national-referral-hospital-an-1my3ul3ugy (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahboub-Schulte, S.; Ali, A.Y.; Khafaji, T. Treating Substance Dependency in the UAE: A Case Study. J. Muslim. Ment. Health 2009, 4, 67–75. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/treating-substance-dependency-in-the-uae-a-case-study-4sov90v0d7 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S.S.; Al-Lawati, A.; Al-Shafaee, M.A.; Duttagupta, K.K. Epidemiological transition of some diseases in Oman: A situational analysis. World Hosp. Health Serv. 2009, 45, 26–31. Available online: https://squ.elsevierpure.com/en/publications/epidemiological-transition-of-some-diseases-in-oman-a-situational-2 (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariffin, N.H.M.; Yusoff, F.H.; Mansor, N.N.A.; Javed, S.; Nazir, S. Assessment of sustainable healthcare management policies and practices in Oman: A comprehensive analysis using an ai-based literature review. Multidiscip. Rev. 2024, 7, 2024257. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/assessment-of-sustainable-healthcare-management-policies-and-5glhwqp5m72r (accessed on 6 April 2025). [CrossRef]

| ALD Stage | Total, n (%) | Age < 50, n/N (%) | Age ≥ 50, n/ (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty liver | 29 (34.5%) | 17/38 (44.7%) | 12/46 (26.1%) | 0.08 |

| Alcoholic hepatitis | 17 (20.2%) | 10/38 (26.3%) | 7/46 (15.2%) | 0.21 |

| Cirrhosis | 34 (40.5%) | 11/38 (28.9%) | 23/46 (50.0%) | 0.048 * |

| HCC | 4 (4.8%) | 0/38 (0.0%) | 4/46 (8.7%) | 0.10 |

| Presentation | Fatty Liver (n = 29), n (%) | Alcoholic Hepatitis (n = 17), n (%) | Cirrhosis (n = 34), n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 13 (44.8%) | 7 (41.2%) | 15 (44.1%) | 0.93 |

| UGIB | 3 (10.3%) | 5 (29.4%) | 10 (29.4%) | 0.21 |

| Abdominal distention | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 5 (14.7%) | 0.030 * |

| Jaundice | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (47.1%) | 3 (8.8%) | 0.001 * |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.61 |

| Trauma (fall) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (17.6%) | 1 (2.9%) | 0.17 |

| Complication | Fatty Liver (n = 29) | Alcoholic Hepatitis (n = 17) | Cirrhosis (n = 34) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No complication (first) | 8 (27.6%) | 6 (35.3%) | 2 (5.9%) | 0.019 * |

| Ascites | 0 (0.0%) → 0 (0.0%) | 3 (17.6%) → 9 (52.9%) | 11 (32.4%) → 26 (76.5%) | <0.001 * |

| UGIB | 2 (6.9%) → 6 (20.7%) | 2 (11.8%) → 5 (29.4%) | 15 (44.1%) → 20 (58.8%) | <0.001 * |

| HE | 0 (0.0%) → 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) → 2 (11.8%) | 1 (2.9%) → 10 (29.4%) | 0.002 * |

| Portal hypertension | 0 (0.0%) → 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) → 6 (35.3%) | 0 (0.0%) → 28 (82.4%) | <0.001 * |

| SBP | — → 0 (0.0%) | — → 2 (11.8%) | — → 9 (26.5%) | 0.064 |

| HCC | 0 (0.0%) → 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) → 1 (5.9%) | 3 (8.8%) → 3 (8.8%) | 0.072 |

| Outcome | Fatty Liver (n = 29), n (%) | Alcoholic Hepatitis (n = 17), n (%) | Cirrhosis (n = 34), n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive | 26 (89.7%) | 10 (58.8%) | 15 (44.1%) | <0.001 * |

| Deceased | 3 (10.3%) | 6 (35.3%) | 15 (44.1%) | |

| Unknown † | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.9%) | 4 (11.8%) |

| Cause | Fatty Liver (n = 3), n (%) | Alcoholic Hepatitis (n = 6), n (%) | Cirrhosis (n = 15), n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 6 (40.0%) | 0.95 |

| Massive UGIB | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 0.89 |

| HRS | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 0.47 |

| Perforated PUD | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0.99 |

| Trauma (fall) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.18 |

| Unknown | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Busafi, S.A.; Al Baluki, T.A.; Alwassief, A. Patterns and Outcomes of Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD) in Oman: A Retrospective Study in a Culturally Conservative Context. Livers 2025, 5, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030038

Al-Busafi SA, Al Baluki TA, Alwassief A. Patterns and Outcomes of Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD) in Oman: A Retrospective Study in a Culturally Conservative Context. Livers. 2025; 5(3):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030038

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Busafi, Said A., Thuwiba A. Al Baluki, and Ahmed Alwassief. 2025. "Patterns and Outcomes of Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD) in Oman: A Retrospective Study in a Culturally Conservative Context" Livers 5, no. 3: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030038

APA StyleAl-Busafi, S. A., Al Baluki, T. A., & Alwassief, A. (2025). Patterns and Outcomes of Alcoholic Liver Disease (ALD) in Oman: A Retrospective Study in a Culturally Conservative Context. Livers, 5(3), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/livers5030038