From Source to Target: The Neutron Pathway for the Clinical Translation of Boron Neutron Capture

Abstract

1. Introduction

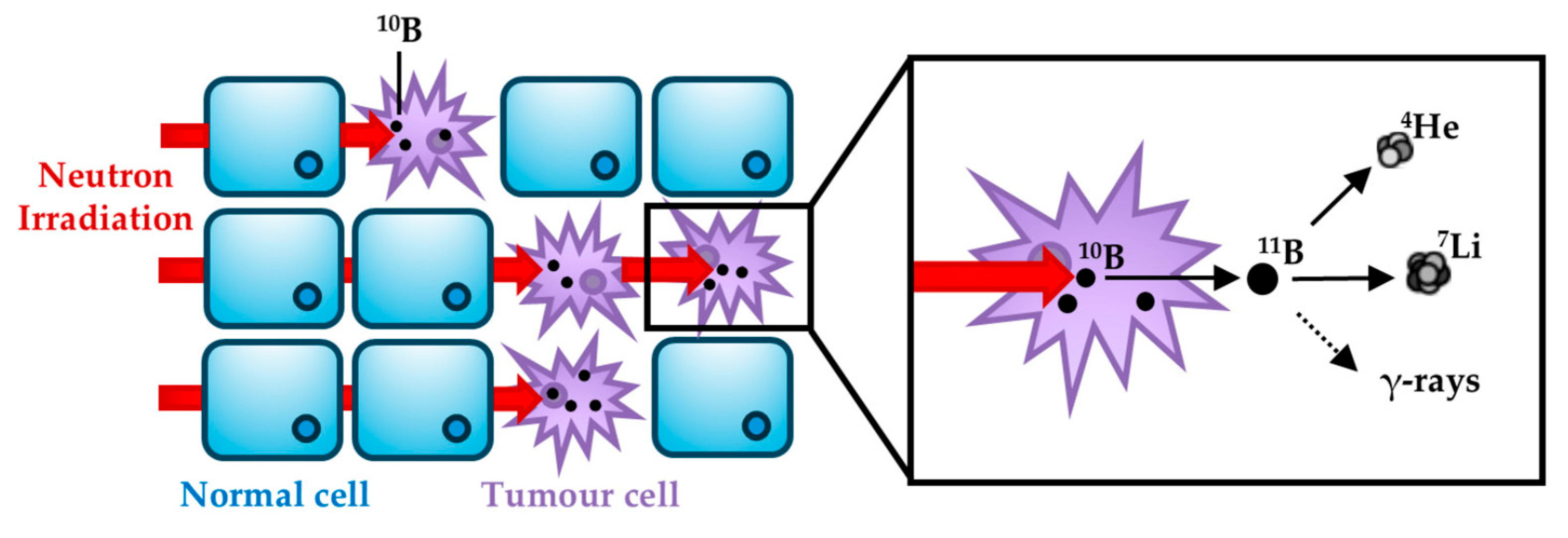

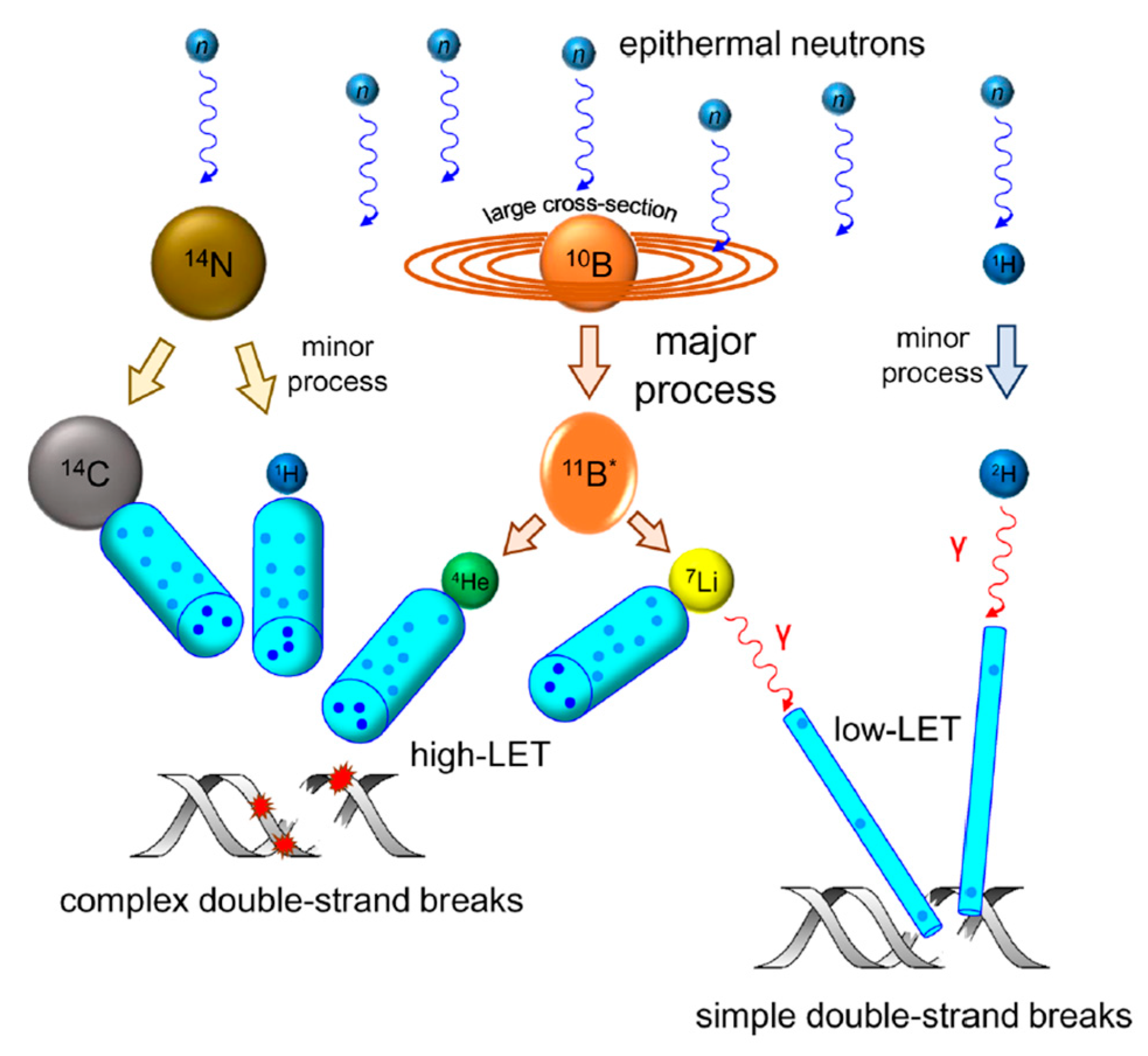

2. Physical and Biological Foundation of BNCT

3. The Physical Rationale

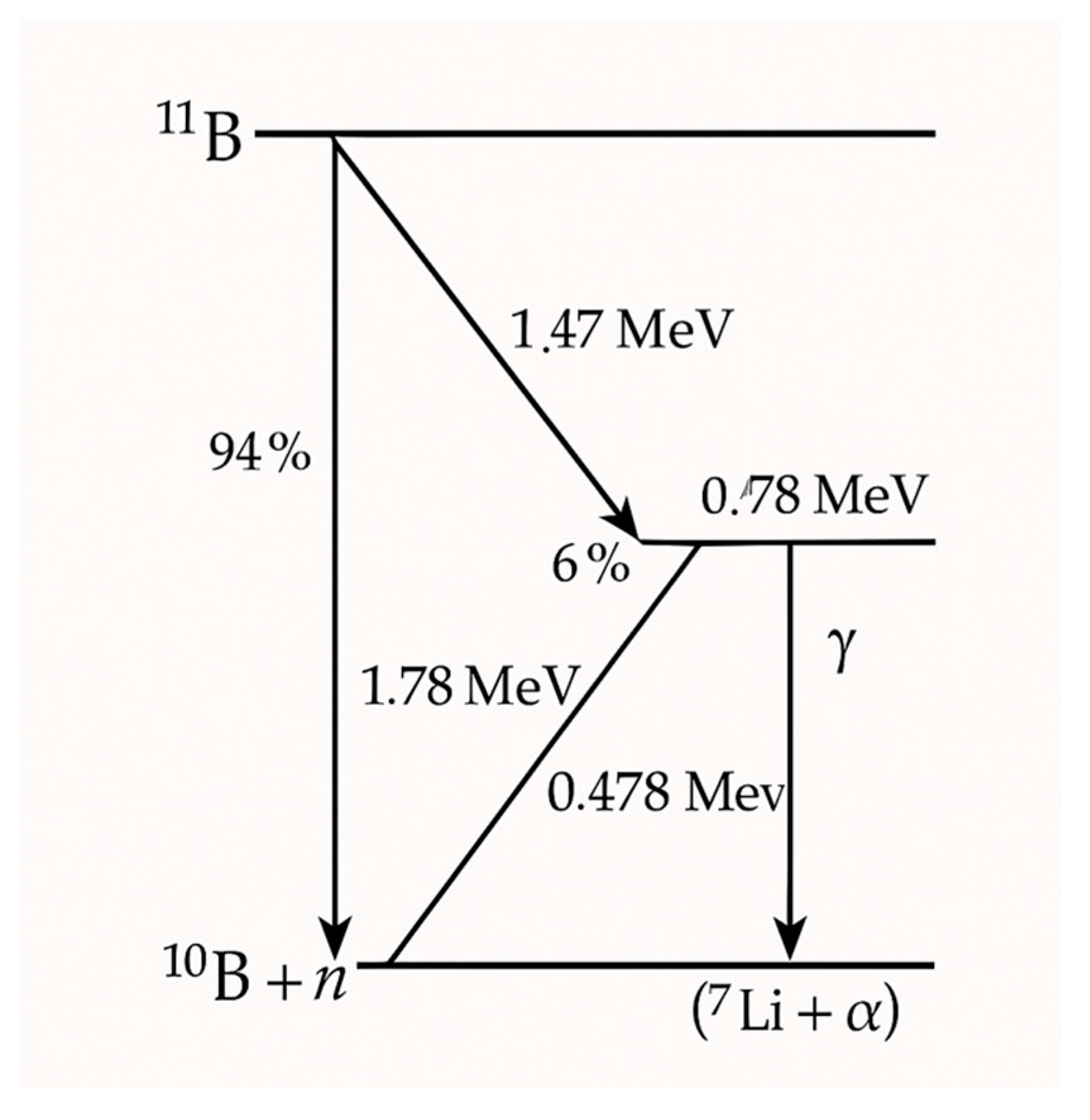

3.1. Neutron–Tissue Interactions

- 10B + n 11B*.

- 11B* α + 7Li.

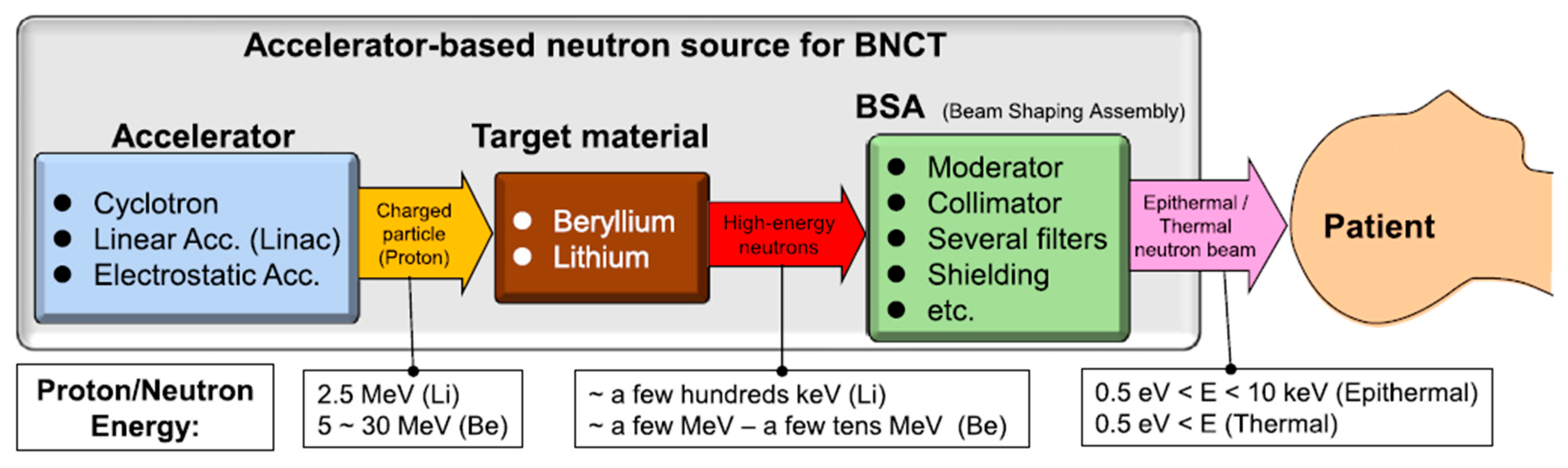

3.2. Neutron Sources and Beam Characteristics

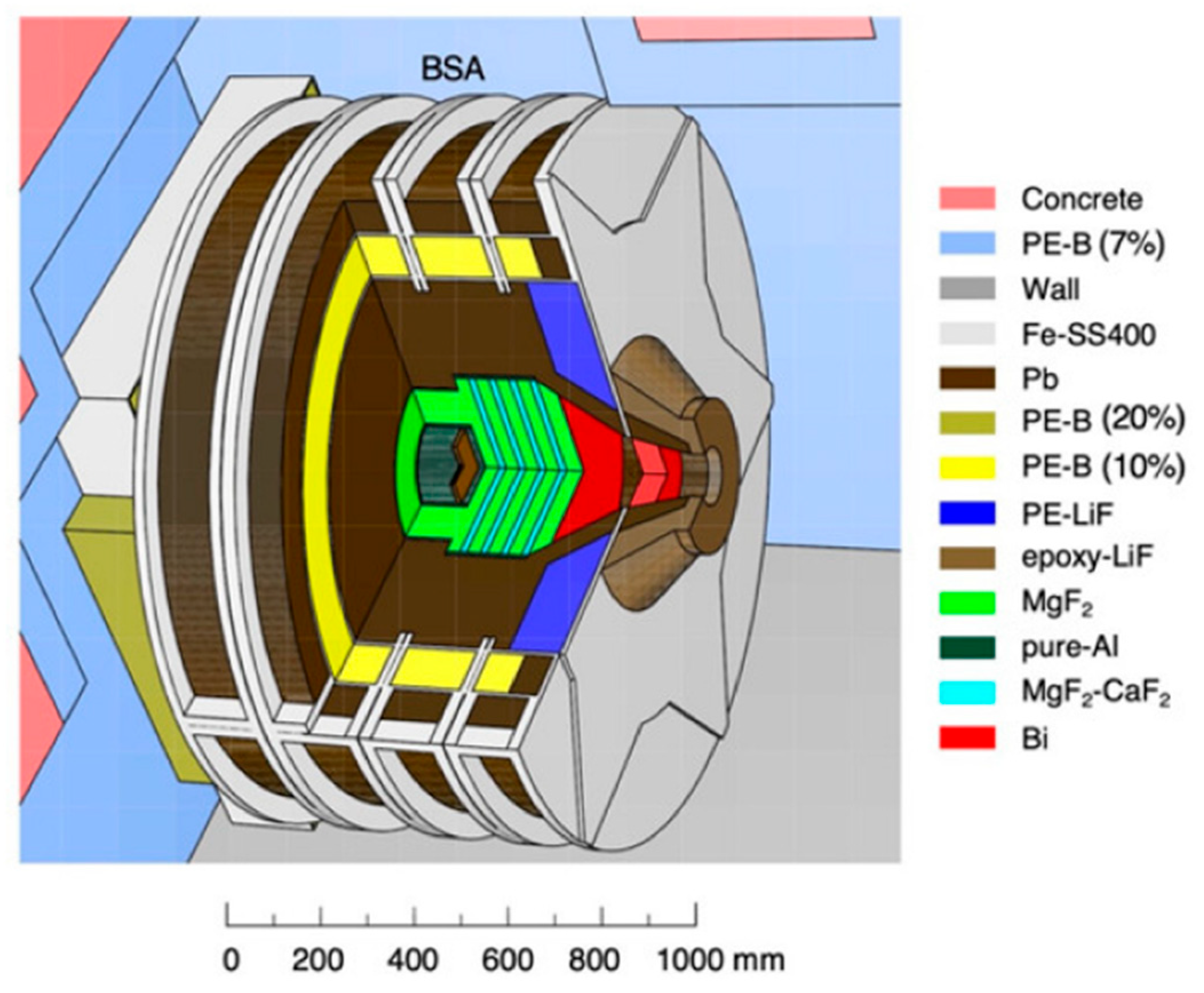

3.3. Neutron Moderation and Energy Spectrum

3.4. Dosimetry in the BNCT Radiation Field

4. The Biological Rationale

4.1. Mechanisms of DNA Damage and Cell Killing

4.2. Boron Delivering Strategies

4.3. Production and Processing of Enriched 10B

5. Closing Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, P.; Tian, S.; Wang, H.; Fan, R.; Liu, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. The basis and advances in clinical application of boron neutron capture therapy. Radiat. Oncol. 2021, 16, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, A.M.; Hu, N. Optimizing boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) to treat cancer: An updated review on the latest developments on boron compounds and strategies. Cancers 2023, 15, 4091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punshon, L.D.; Fabbrizi, M.R.; Phoenix, B.; Green, S.; Parsons, J.L. Current insights into the radiobiology of boron neutron capture therapy and the potential for further improving biological effectiveness. Cells 2024, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locher, G.L. Biological effects and therapeutic possibilities of neutrons. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. Nucl. Med. 1936, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sweet, W.H.; Javid, M. The possible use of neutron-capturing isotopes such as boron 10 in the treatment of neoplasms. I. Intracranial tumors. J. Neurosurg. 1952, 9, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatanaka, H.; Sano, K. A revised boron-neutron capture therapy for malignant brain tumours. I. Experience on terminally ill patients after Co-60 radiotherapy. Z. Neurol. 1973, 204, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairchild, R.G.; Gabel, D.; Laster, B.H.; Greenberg, D.; Kiszenick, W.; Micca, P.L. Microanalytical techniques for boron analysis using the 10B(n,α)7Li reaction. Med. Phys. 1986, 13, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Nitta, K.; Yagihashi, T.; Eide, P.; Koivunoro, H.; Sato, N.; Gotoh, S.; Shiba, S.; Omura, M.; Nagata, H.; et al. Initial Evaluation of Accelerator-Based Neutron Source System at the Shonan Kamakura General Hospital. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2023, 199, 110898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porra, L.; Wendland, L.; Seppälä, T.; Koivunoro, H.; Revitzer, H.; Tervonen, J.; Kankaanranta, L.; Anttonen, A.; Tenhunen, M.; Joensuu, H. From Nuclear Reactor-Based to Proton Accelerator-Based Therapy: The Finnish Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Experience. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2023, 38, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouff, T.D.; Seneviratne, D.S.; Ebner, D.K.; Stross, W.C.; Waddle, M.R.; Trifiletti, D.M.; Krishnan, S. Boron neutron capture therapy: A review of clinical applications. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 601820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Igawa, K.; Kasai, T.; Sadahira, T.; Wang, W.; Watanabe, T.; Bekku, K.; Katayama, S.; Iwata, T.; Hanafusa, T.; et al. The current status and novel advances of boron neutron capture therapy clinical trials. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2024, 14, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Using CICS-1 and SPM-011 for Malignant Melanoma and Angiosarcoma. Identifier: NCT04293289. Updated 2023-02-08. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04293289 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Karihtala, P. The current status and future perspectives of clinical boron neutron capture therapy trials. Health Technol. 2024, 14, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, I.; González, S.; Herrera, M.S.; Provenzano, L.; Ferrarini, M.; Magni, C.; Protti, N.; Fatemi, S.; Vercesi, V.; Battistoni, G.; et al. A Novel Approach to Design and Evaluate BNCT Neutron Beams Combining Physical, Radiobiological and Dosimetric Figures of Merit. Biology 2021, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Advances in Boron Neutron Capture Therapy; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2023; ISBN 978-92-0-132723-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hamermesh, B.; Ringo, G.R.; Wexler, S. The thermal neutron capture cross section of hydrogen. Phys. Rev. 1953, 90, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, P.; Praena, J.; Porras, I.; Sabaté-Gilarte, M.; Lederer-Woods, C.; Aberle, O.; Alcayne, V.; Amaducci, S.; Andrzejewski, J.; Audouin, L.; et al. Measurement of the N14(n,p)C14 cross section at the CERN n_TOF facility from subthermal energy to 800 keV. Phys. Rev. C 2023, 107, 064617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughabghab, S.F. Atlas of Neutron Resonances: Resonance Parameters and Thermal Cross Sections Z = 1–100, 6th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 978-0-444-63744-2. [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick, M.; Herman, M.; Obložinský, P.; Dunn, M.; Danon, Y.; Kahler, A.; Smith, D.; Pritychenko, B.; Arbanas, G.; Arcilla, R.; et al. ENDF/B-VII.1 Nuclear Data for Science and Technology: Cross Sections, Covariances, Fission Product Yields and Decay Data. Nucl. Data Sheets 2011, 112, 2887–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikchurina, M.; Bykov, T.; Ibrahim, I.; Kasatova, A.; Kasatov, D.; Kolesnikov, I.; Konovalova, V.; Kormushakov, T.; Koshkarev, A.; Kuznetsov, A.; et al. Dosimetry for boron neutron capture therapy developed and verified at the accelerator based neutron source VITA. Front. Nucl. Eng. 2023, 2, 1266562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumada, H.; Sakae, T.; Sakurai, H. Current development status of accelerator based neutron source for boron neutron capture therapy. EPJ Techn. Instrum. 2023, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, S.; Protti, N. A brief review on reactor based neutron sources for boron neutron capture therapy. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, K.; Konno, A.; Hiratsuka, J.; Yoshimoto, S.; Kato, T.; Ono, K.; Otsuki, N.; Hatazawa, J.; Tanaka, H.; Takayama, K.; et al. Boron neutron capture therapy using cyclotron-based epithermal neutron source and borofalan (10B) for recurrent or locally advanced head and neck cancer (JHN002): An open-label phase II trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 155, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.A.; Smirnov, A.N.; Taskaev, S.Y.; Bayanov, B.F.; Belchenko, Y.I.; Davydenko, V.I.; Dunaevsky, A.; Emelev, I.S.; Kasatov, D.A.; Makarov, A.N.; et al. Accelerator-based neutron source for boron neutron capture therapy. Uspekhi Fiz. Nauk. 2022, 192, 893–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskaev, S.; Berendeev, E.; Bikchurina, M.; Bykov, T.; Kasatov, D.; Kolesnikov, I.; Koshkarev, A.; Makarov, A.; Ostreinov, G.; Porosev, V.; et al. Neutron Source Based on Vacuum-Insulated Tandem Accelerator and Lithium Target. Biology 2021, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuya, Y.; Kai, T.; Sato, T.; Ogawa, T.; Hirata, Y.; Yoshii, Y.; Parisi, A.; Liamsuwan, T. Track-structure modes in particle and heavy ion transport code system (PHITS): Application to radiobiological research. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2022, 98, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, S.; Guo, H.; Qi, Y.; Yang, G.; Huang, Y. A portable fast neutron irradiation system for tumor therapy. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2020, 160, 109138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumada, H.; Takada, K.; Tanaka, S.; Matsumoto, Y.; Naito, F.; Kurihara, T.; Sugimura, T.; Sato, M.; Matsumura, A.; Sakurai, H.; et al. Evaluation of the characteristics of the neutron beam of a linac-based neutron source for boron neutron capture therapy. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2020, 165, 109246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capoulat, M.E.; Cartelli, D.; Baldo, M.; Sandín, J.S.; Del Grosso, M.; Bertolo, A.; Gaviola, P.; Igarzábal, M.; Conti, G.; Gun, M.; et al. Accelerator based-BNCT facilities worldwide and an update of the Buenos Aires project. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2025, 219, 111723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W.; Li, Q. Design of beam shaping assemblies for accelerator-based BNCT with multi-terminals. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 642561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Tanaka, H.; Akita, K.; Kakino, R.; Aihara, T.; Nihei, K.; Ono, K. Accelerator based epithermal neutron source for clinical boron neutron capture therapy. J. Neutron Res. 2022, 24, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PR Newswire. Neutron Therapeutics and Helsinki University Hospital Treat First Patients in Phase 1 Trial of Boron Neutron Capture Therapy; PR Newswire: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://go.gale.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CA839961052 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Pisent, A.; Grespan, F.; Baltador, C. ANTHEM Project, construction of a RFQ driven BNCT neutron source. In Proceedings of the 32nd Linear Accelerator Conference (LINAC 2024), Chicago, IL, USA, 25–30 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikchurina, M.; Bykov, T.; Byambatseren, E.; Ibrahem, I.; Kasatov, D.; Kolesnikov, I.; Konovalova, V.; Koshkarev, A.; Makarov, A.; Ostreinov, G.; et al. VITA high flux neutron source for various applications. J. Neutron Res. 2022, 24, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, T.; Yoshihashi, S.; Tanagami, Y.; Tsuchida, K.; Honda, S.; Yamazaki, A.; Watanabe, K.; Kiyanagi, Y.; Uritani, A. Neutronics analyses of the radiation field at the accelerator-based neutron source of Nagoya University for the BNCT study. J. Nucl. Eng. 2022, 3, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleuel, D.L.; Donahue, R.J.; Ludewigt, B.A.; Vujic, J. Designing accelerator-based epithermal neutron beams for boron neutron capture therapy. Med. Phys. 1998, 25, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonai, S.; Aoki, T.; Tahara, Y.; Manabe, M.; Hatanaka, H.; Nakagawa, K. Feasibility study on epithermal neutron field for cyclotron-based boron neutron capture therapy. Med. Phys. 2003, 30, 2021–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H.; Sakurai, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Takata, T.; Masunaga, S.; Kinashi, Y.; Kashino, G.; Liu, Y.; Mitsumoto, T.; Yajima, S.; et al. Improvement of dose distribution in phantom by using epithermal neutron source based on the Be(p,n) reaction using a 30 MeV proton cyclotron accelerator. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2009, 67, S258–S261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, M.; Sauzet, N.; Santos, D. On the epithermal neutron energy limit for accelerator-based BNCT: Study and impact of new energy limits. Phys. Med. 2021, 88, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Suzuki, M.; Masunaga, S.; Kashino, G.; Kinashi, Y.; Chen, Y.-W.; Liu, Y.; Uehara, K.; Mitsumoto, T.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Experimentally determined relative biological effectiveness of cyclotron-based epithermal neutrons designed for clinical BNCT: In vitro study. J. Radiat. Res. 2023, 64, 811–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, H.; Dian, E.; Mezei, F.; Sipos, P.; Czifrus, S. An accelerator-based neutron source design with a thermal neutron port and an epithermal neutron port for boron neutron capture therapy. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2025, 217, 111647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, N.S.; Shabani, D.; Li, J.; Zakalek, P.; Mauerhofer, E.; Dawidowski, J.; Gutberlet, T. Development of an epithermal and fast neutron target station for the High Brilliance Neutron Source. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2025, 140, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). Relative biological effectiveness (RBE), quality factor (Q), and radiation weighting factor (wR). Ann. ICRP 2003, 33, 1–117. [Google Scholar]

- International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. ICRP Publication 103. Ann. ICRP 2007, 37, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Kang, J.O. Basics of particle therapy II: Relative biological effectiveness. Radiat. Oncol. J. 2012, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa-Rivera, M.; Praena, J.; Porras, I.; Sabariego, M.P.; Köster, U.; Haertlein, M.; Forsyth, V.T.; Ramírez, J.C.; Jover, C.; Jimena, D.; et al. Thermal neutron relative biological effectiveness factors for boron neutron capture therapy from in vitro irradiations. Cells 2020, 9, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassow, J.; Sauerwein, W.; Wittig, A.; Bourhis-Martin, E.; Hideghéty, K.; Moss, R. Advantage and limitations of weighting factors and weighted dose quantities and their units in boron neutron capture therapy. Med. Phys. 2004, 31, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Masunaga, S.I.; Kumada, H.; Hamada, N. Microdosimetric modeling of biological effectiveness for boron neutron capture therapy considering intra- and intercellular heterogeneity in 10B distribution. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, H. Response of normal tissues to boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) with 10B-BSH and 10B-BPA. Cells 2021, 10, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Geng, C.; Kondo, J.N.D.; Li, M.; Méndez, J.R.; Altieri, S.; Liu, Y.; Tang, X. Microdosimetric analysis for boron neutron capture therapy via Monte Carlo track structure simulation with modified lithium cross sections. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2023, 209, 110956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.J.; Pozzi, E.C.C.; Hughes, A.M.; Provenzano, L.; Koivunoro, H.; Carando, D.G.; Thorp, S.I.; Casal, M.R.; Bortolussi, S.; Trivillin, V.A.; et al. Photon iso-effective dose for cancer treatment with mixed field radiation based on dose-response assessment from human and an animal model: Clinical application to BNCT for head and neck cancer. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 7938–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardini, G.F.P.; Bortolussi, S.; Koivunoro, H.; Provenzano, L.; Ferrari, C.; Cansolino, L.; Postuma, I.; Carando, D.G.; Kankaanranta, L.; Joensuu, H.; et al. Comparison of photon isoeffective dose models based on in vitro and in vivo radiobiological experiments for head and neck cancer treated with BNCT. Radiat. Res. 2022, 198, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, I.; Magni, C.; Marcaccio, B.; Fatemi, S.; Vercesi, V.; Ciocca, M.; Magro, G.; Orlandi, E.; Vischioni, B.; Ronchi, S.; et al. Using the photon isoeffective dose formalism to compare and combine BNCT and CIRT in a head and neck tumour. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, V.; Bianchi, A.; Selva, A. Boron neutron capture therapy: Microdosimetry at different boron concentrations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Geng, C.; Tang, X.; Tian, F.; Zhao, S.; Qi, J.; Shu, D.; Gong, C. Boron concentration prediction from Compton camera image for boron neutron capture therapy based on generative adversarial network. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2022, 186, 110302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, P.; Lerendegui-Marco, J.; Balibrea-Correa, J.; Babiano-Suárez, V.; Gameiro, B.; Ladarescu, I.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, P.; Daugas, J.-M.; Koester, U.; Michelagnoli, C.; et al. The Potential of the i-TED Compton Camera Array for Real-Time Boron Imaging and Determination during Treatments in Boron Neutron Capture Therapy. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2025, 217, 111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, S.Y.; Fu, D.; Takata, T.; Tanaka, H.; Suzuki, M. Real-time estimation of boron concentration using an improved gamma-ray telescope system for boron neutron capture therapy. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2025, 226, 112231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caracciolo, A.; Mazzucconi, D.; Ferri, T.; Grisoni, L.; Ghisio, F.; Piroddi, M.; Borghi, G.; Carminati, M.; Agosteo, S.; Tsuchida, K.; et al. Prompt Gamma-Ray Imaging in Realistic Background Conditions of a Boron Neutron Capture Therapy Facility. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedjani, A.; Abdi, R.; Boumala, D.; Belafrites, A.; Groetz, J.-E. Boron neutron capture therapy: Dosimetric evaluation of a brain tumor and surrounding healthy tissues using Monte Carlo simulation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 2022, 1040, 167240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizi, M.R.; Nickson, C.M.; Hughes, J.R.; Robinson, E.A.; Vaidya, K.; Rubbi, C.P.; Kacperek, A.; Bryant, H.E.; Helleday, T.; Parsons, J.L. Targeting OGG1 and PARG radiosensitises head and neck cancer cells to high-LET protons through complex DNA damage persistence. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melia, E.; Parsons, J.L. DNA damage and repair dependencies of ionising radiation modalities. Biosci. Rep. 2023, 43, BSR20222586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechetin, G.V.; Zharkov, D.O. DNA damage response and repair in boron neutron capture therapy. Genes. 2023, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliszewska-Olejniczak, K.; Kaniowski, D.; Araszkiewicz, M.T.; Tyminska, K.; Korgul, A. Molecular mechanisms of specific cellular DNA damage response and repair induced by the mixed radiation field during boron neutron capture therapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 676575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.H.; Seldon, C.; Butkus, M.; Sauerwein, W.; Giap, H.B. A review of boron neutron capture therapy: Its history and current challenges. Int. J. Part. Ther. 2022, 9, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; He, P.; Wei, Y.; Qu, C.; Tang, F.; Li, Y. Application and perspectives of nanomaterials in boron neutron capture therapy of tumors. Cancer Nano 2025, 16, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kang, H.G.; Xu, H.-Z.; Luo, H.; Suzuki, M.; Lan, Q.; Chen, X.; Komatsu, N.; Zhao, L. Tumor eradication by boron neutron capture therapy with 10B-enriched hexagonal boron nitride nanoparticles grafted with poly(glycerol). Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2301479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, K.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, T. Boron carbide nanoparticles for boron neutron capture therapy. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 10717–10730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luderer, M.J.; Muz, B.; Alhallak, K.; Sun, J.; Wasden, K.; Guenthner, N.; de la Puente, P.; Federico, C.; Azab, A.K. Thermal sensitive liposomes improve delivery of boronated agents for boron neutron capture therapy. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminade, A.-M.; Rodríguez, F.; Gramage-Doria, R. Dendritic structures functionalized with boron clusters, in view of BNCT. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.Y.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Huang, S.-C.; Huang, W.-Y.; Hsu, F.-T.; Lee, H.-Y.; Wang, T.-W.; Keng, P.Y. Boron neutron capture therapy enhanced by boronate ester polymer micelles: Synthesis, stability, and tumor inhibition studies. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 4215–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Ma, L.; Tong, J.; Zuo, N.; Hu, W.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J.; Liang, T.; Liu, Q. Boron-peptide conjugates with angiopep-2 for boron neutron capture therapy. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1199881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, V.G.S.S.; Kommineni, N. Peptide conjugated boron neutron capture therapy for enhanced tumor targeting. Nanotheranostics 2024, 8, 458–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyeva, M.A.; Dymova, M.A.; Novopashina, D.S.; Kuligina, E.V.; Timoshenko, V.V.; Kolesnikov, I.A.; Taskaev, S.Y.; Richter, V.A.; Venyaminova, A.G. Tumor cell-specific 2’-fluoro RNA aptamer conjugated with closo-dodecaborate as a potential agent for boron neutron capture therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudawska, A.; Szermer-Olearnik, B.; Szczygieł, A.; Mierzejewska, J.; Węgierek-Ciura, K.; Żeliszewska, P.; Kozień, D.; Chaszczewska-Markowska, M.; Adamczyk, Z.; Rusiniak, P.; et al. Functionalized boron carbide nanoparticles as active boron delivery agents dedicated to boron neutron capture therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 6637–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oloo, S.O.; Smith, K.M.; Vicente, M.D.G.H. Multi-functional boron-delivery agents for boron neutron capture therapy of cancers. Cancers 2023, 15, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranco, A.; Alberti, D.; Parisotto, S.; Renzi, P.; Lecomte, V.; Crich, S.G.; Deagostino, A. Biotinylation of a MRI/Gd BNCT theranostic agent to access a novel tumour-targeted delivery system. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2022, 20, 5342–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, A.; Demichelis, M.P.; Di Martino, G.; Postuma, I.; Bortolussi, S.; Falqui, A.; Milanese, C.; Ferrara, C.; Sommi, P.; Anselmi-Tamburini, U. Synthesis and characterization of Gd-functionalized B4C nanoparticles for BNCT applications. Life 2023, 3, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, Y.; Andoh, T.; Kawabata, S.; Hu, N.; Michiue, H.; Nakamura, H.; Nomoto, T.; Suzuki, M.; Takata, T.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Proposal of recommended experimental protocols for in vitro and in vivo evaluation methods of boron agents for neutron capture therapy. J. Radiat. Res. 2023, 64, 859–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-T.; Cheng, K.; Liu, B.; Cao, Y.-C.; Fan, J.-X.; Liu, Z.-G.; Zhao, Y.-D. Recent progress of nano-drugs in neutron capture therapy. Theranostics 2024, 14, 3193–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCandless, F.P.; Herbst, R.S. Separation of the Isotopes of Boron by Chemical Exchange Reactions. U.S. Patent 5,419,887, 30 May 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Mu, Y.; Li, X.; Bai, P. Advances in boron-10 isotope separation by chemical exchange distillation. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2010, 37, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-P. Studies on separation process and production technology of boron isotope. J. Isot. 2014, 27, 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, J.; Sun, J. Process intensification of chemical exchange method for boron isotope separation using micro-channel distillation technology. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoroshilov, A.V. Separation of boron isotopes by chemical exchange in liquid–liquid systems. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1099, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, P.I.; Khoroshilov, A.V.; Panyukova, N.S. Experimental modeling of boron-10 isotope enrichment during chemical exchange in a liquid–liquid system. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 98, 2891–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, Y.; Aida, M.; Okamoto, M.; Kakihana, H. Boron isotope separation by ion exchange chromatography using weakly basic anion exchange resin. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1980, 53, 1860–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gao, R.; Bai, P. Advances in boron isotope separation by ion exchange chromatography. Asian J. Chem. 2014, 26, 2187–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, J.F.; Chen, H.; Liang, K.; Liu, J.; Cox, S.E.; Halliday, A.N.; Yang, Y. Liquid solution centrifugation for safe, scalable, and efficient isotope separation. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg8993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letokhov, V.S. Laser-induced separation of isotopes. At. Energy 1987, 62, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Lv, X.; Fu, K. Studies of irradiation products of laser boron isotope separation by infrared absorption spectroscopy. Chin. Phys. 1982, 2, 2. [Google Scholar]

- University of California; U.S. Department of Energy. Method of Separating Boron Isotopes. U.S. Patent 4,447,303, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, G.N. Laser separation of boron isotopes: Research results and options for technological implementation. Phys.-Uspekhi 2025, 68, 452–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Times. China Achieves Breakthrough in Low-Temperature Distillation of Boron-10 Isotopes to Support Nuclear Safety. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecns.cn/news/sci-tech/2024-10-10/detail-ihehxcae7641285.shtml (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- China Nuclear Energy Association (CNEA). China’s Breakthrough in Boron-10 Isotope Separation Technology. 2024. Available online: https://en.china-nea.cn/site/content/47860.html (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Laptev, V.B.; Makarov, G.N.; Petin, A.N.; Pigul’sKii, S.V.; Ryabov, E.A. Production of a Highly Enriched 10B Isotope by a Combined Method of Laser Separation and Rectification. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophy 2025, 98, 1537–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Xu, J. Preparation and characterization of 10B boric acid with high purity for nuclear industry. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Terranova, M.L. From Source to Target: The Neutron Pathway for the Clinical Translation of Boron Neutron Capture. J. Nucl. Eng. 2026, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne7010006

Terranova ML. From Source to Target: The Neutron Pathway for the Clinical Translation of Boron Neutron Capture. Journal of Nuclear Engineering. 2026; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerranova, Maria Letizia. 2026. "From Source to Target: The Neutron Pathway for the Clinical Translation of Boron Neutron Capture" Journal of Nuclear Engineering 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne7010006

APA StyleTerranova, M. L. (2026). From Source to Target: The Neutron Pathway for the Clinical Translation of Boron Neutron Capture. Journal of Nuclear Engineering, 7(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/jne7010006