3.1. Model Validation and Comparative Analysis

The above simulation results were compared against the published findings of Wang et al. [

6], as shown in

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7. Wang’s study used a very similar geometry (a 1:10-scaled model based on the CORRIDA loop) and likewise treated the gas–liquid interface as a constant-concentration boundary. They explored the effects of inlet oxygen content, interface oxygen concentration, flow rate, and temperature on oxygen mass transfer, ultimately formulating an empirical correlation for oxygen transport [

6]. Overall, our simulation agrees with Wang et al. on the qualitative trends: increasing flow rate and temperature both enhance oxygen transfer, whereas the initial oxygen content in the liquid and the exact value of the interface concentration have relatively minor influence on the mass transfer coefficient (provided the interface is maintained at saturation) [

6]. These parallels indicate that our model captures the fundamental physics similarly to Wang’s work. The present study extends Wang et al.’s work by investigating a broader range of inlet flow velocities and temperature conditions. Additionally, the legend resolution in all parametric study tables (

Table 5 and

Table 6) has been enhanced for improved readability, and differences in legend positioning reflect the default visualization settings of ANSYS Fluent and STAR-CCM+.

Table 7 shows the comparison of average mass transfer coefficients between literature results and present computational results, including mass flow rate, interface area, inlet average oxygen concentration, outlet average oxygen concentration, bulk average oxygen concentration, interfacial oxygen concentration, and average mass transfer coefficient. Quantitatively, however, there are some discrepancies. Our steady-state results tend to predict slightly lower oxygen concentrations in the LBE than those reported by Wang et al. under comparable conditions [

6]. For example, for a given flow rate (0.1 kg/s in the loop) and inlet oxygen of

wt%, we obtained an outlet oxygen concentration on the order of

wt%, whereas Wang’s correlation implies a somewhat higher value (the exact number is not directly stated in their paper) [

6]. One likely reason is a difference in the assumed interface oxygen concentration. Wang et al. mention that they varied the boundary oxygen concentration in their parametric study, but the specific value used for each scenario is not clearly stated. If their simulation for the comparable case used a higher oxygen partial pressure in the cover gas (leading to an interface concentration above the

wt% that we used), it would naturally result in a higher oxygen uptake in the liquid. In other words, our simulation may be operating with a smaller driving concentration difference than in Wang’s case, hence the lower oxygen levels. Indeed, in a related study by Li et al. [

22], the interface oxygen concentration was set as high as

wt%, which significantly boosts the oxygen transfer compared to our

wt%. Aside from boundary conditions, scaling assumptions could also play a role. Both studies use a scaled-down model of the oxygen contact device, but Wang et al. did not elaborate on whether parameters such as flow velocity or surface roughness were adjusted to reflect full-scale conditions. If those details differ, they could affect the mass transfer outcomes. Despite these differences, the order of magnitude of all results is the same, and the Sherwood number or mass transfer coefficients obtained are in reasonable agreement (within a factor of about 1.5–2). Wang et al. reported that their proposed 1D correlation predicts the 3D simulation results within

uncertainty, which gives a sense of the expected variation. The deviations between our findings and Wang’s thus fall within a not-unexpected range, given the sensitivity of oxygen transport to exact operating conditions [

6].

To verify the reliability of the above results, steady-state calculations are performed using STAR-CCM+ software and the results are compared with those in Li et al. [

22] study, as shown in

Table 8,

Table 9 and

Table 10. The numerical models implemented in STAR-CCM+ and ANSYS Fluent are essentially the same: both employ the finite volume method to solve the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations coupled with the species transport equation, and both use the standard

k–

turbulence model with Enhanced Wall Treatment. The primary difference lies in their discretization schemes and solver algorithms. STAR-CCM+ and Fluent simulations serve as cross-validation to ensure model accuracy and robustness, rather than to explore fundamentally different physical models. In many respects, our work and Li’s study arrive at similar conclusions. Both emphasize that oxygen transport in flowing LBE is governed by convection-enhanced diffusion and that the overall mass transfer coefficient increases with flow rate and temperature [

22]. Li et al. also found that the gas–liquid interface concentration has little effect on the mass transfer coefficient and that lower initial oxygen content in the LBE yields a slightly higher average mass transfer coefficient—observations that our simulation supports, as discussed above [

22]. Furthermore, Li’s simulation of an oxygen control loop (also based on the CORRIDA design) produced outlet oxygen concentration levels on the order of

wt%, comparable to what we predict when operating under similar conditions (e.g., at an inlet oxygen of

wt% and an interface of

wt%, Li et al. reported

wt% at the outlet, whereas we obtained

wt%) [

22]. This close agreement in magnitude is encouraging.

Despite the generally consistent trends, there are some quantitative gaps between our results and Li’s. Notably, the average mass transfer coefficient inferred from our simulations is slightly lower than that reported by Li et al. [

22]. For the scenario mentioned above, our two CFD codes yielded average oxygen mass transfer coefficients of approximately 0.6–0.7 (in normalized units), whereas Li et al. [

22] reported about 0.86. This indicates that our model predicts a somewhat more conservative (lower) oxygen transfer rate. The discrepancy may stem from differences in turbulence modeling details. Li’s study does not explicitly specify the turbulence model or certain parameters like the turbulent Schmidt number, turbulence intensity, etc. In our simulations, we used the standard

k–

turbulence model with Enhanced Wall Treatment and set a turbulent Schmidt number of 0.9 (as noted earlier in the methodology). If Li et al. used a different turbulence approach or default parameters, the resulting mixing intensity in the near-interface region could differ, leading to a higher mass transfer coefficient in their case [

22]. Oxygen transfer in LBE is highly sensitive to how turbulence convects species from the interface into the bulk (since it is a convection–diffusion process), so even relatively small differences in turbulence assumptions can cause noticeable changes in the outcome. Another factor could be numerical resolution: our model employed an adaptive hexahedral mesh with about 1.5 million cells and was validated for grid independence, which might not have been the case in earlier studies—if a coarser mesh was used by Li et al. [

22], it could under-resolve steep concentration gradients, ironically possibly necessitating a higher effective diffusion (or turbulence) to match experimental data, thus altering the calibrated mass transfer coefficient. In any event, when we implemented the same inlet flow (0.5 kg/s) and boundary conditions as Li’s case, our predictions were within ∼15–20% of Li’s results for outlet oxygen level and mass transfer coefficient. This level of agreement is quite reasonable in engineering terms [

22]. Sensitivity to turbulence model selection (standard vs. realizable

k–

vs. SST

k–

) will be addressed in future work.

In summary, the present computational model demonstrates good qualitative and quantitative agreement with the existing literature on oxygen diffusion in LBE loops, with some improvements in certain aspects. For example, our approach provides a clearer handling of the gas–liquid interface (by firmly linking it to equilibrium thermodynamics) and uses well-defined turbulence parameters, which lend confidence to the predictive capability of the model. Indeed, our model showed improved accuracy in calculating the oxygen content distribution in the CORRIDA loop compared to Li’s earlier simulation [

22]. Remaining discrepancies between our results and prior studies can be explained by differences in boundary conditions and modeling assumptions, as discussed above. By reconciling these differences, the validity of the proposed model is strengthened. Therefore, this model can be confidently utilized for further investigation into the detailed transport phenomena within the system.

3.2. Steady-State Analysis of Flow Field and Oxygen Distribution

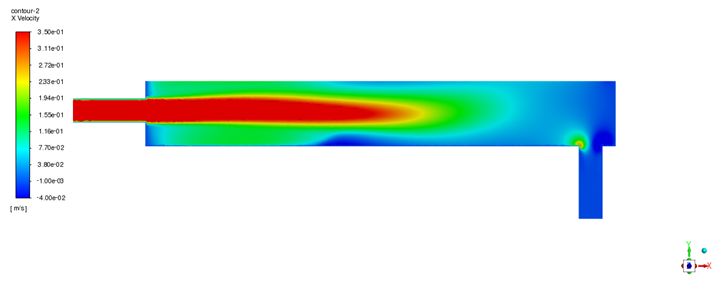

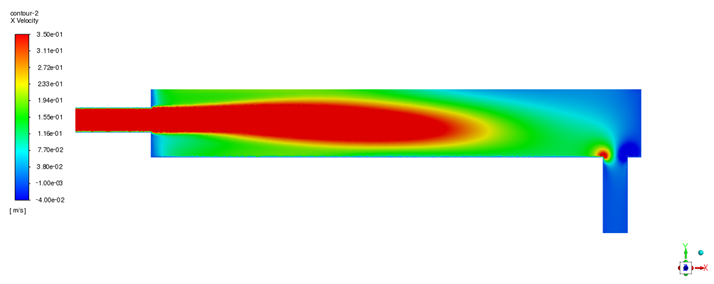

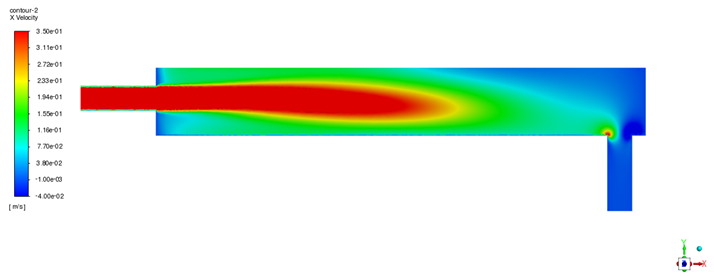

Having established the model’s predictive capability, steady-state simulations were performed using both ANSYS Fluent and STAR-CCM+ to analyze the baseline flow field and oxygen distribution within the device. The velocity field obtained from both solvers (illustrated in

Figure 5 for Fluent and

Figure 6 for STAR-CCM+) shows a consistent flow pattern through the oxygen transfer device. All figure legends have been enhanced for improved legibility. The apparent differences in legend positions between

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 (and other solver comparison figures) reflect the default legend placement settings of ANSYS Fluent and STAR-CCM+; however, the actual scale ranges and legend sizes are comparable between the two solvers. LBE enters through the inlet pipe and spreads horizontally along the bottom of the container toward the outlet. The flow is predominantly uniform in the bulk of the liquid region, but a small recirculation zone is observed near the inlet. This recirculation eddy keeps fluid circulating close to the gas–liquid interface in the inlet region, thereby prolonging its contact with the oxygen source. As a result, there is a tendency for oxygen enrichment in the upper layer of LBE near the inlet side. Overall, the velocity distributions from Fluent and STAR-CCM+ are in good agreement, with only minor quantitative differences in the turbulence details. This cross-validation of the flow field builds confidence that the hydrodynamic behavior is captured accurately by the model.

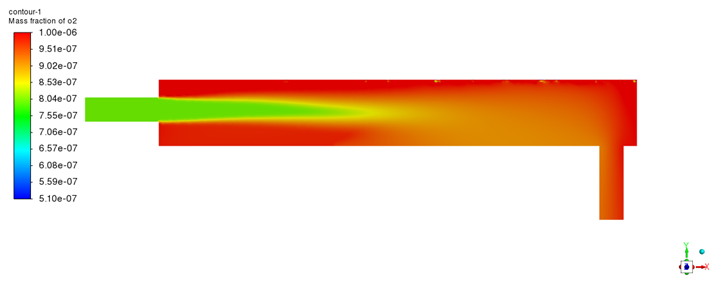

The steady-state oxygen concentration distribution in the LBE is shown in

Figure 7 (Fluent) and

Figure 8 (STAR-CCM+). Both simulations reveal that oxygen dissolves from the interface into the liquid, creating a pronounced concentration gradient in the vertical direction. As expected, the highest oxygen concentration occurs at the gas–liquid interface, where the liquid is in equilibrium with the oxygen gas. In our model, the interface oxygen content is fixed at the equilibrium concentration for the operating temperature. This boundary condition is justified by the much faster diffusion of oxygen in the gas phase compared to liquid LBE, allowing the interface to be instantaneously replenished with oxygen from the gas.

From the interface, the oxygen concentration decreases markedly with depth into the LBE, indicating that diffusion into the bulk liquid is relatively slow. Indeed, oxygen transport in LBE is limited by the low diffusivity, so a high concentration remains localized near the interface while the bulk of the fluid is less oxygen-rich. By the time the fluid reaches the outlet, the average oxygen concentration in the liquid has dropped to the order of

wt%. Quantitatively, Fluent predicts an outlet oxygen concentration of about

wt%, whereas STAR-CCM+ predicts about

wt%. Color scales between

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 have been standardized for direct comparison; differences remaining are attributable to discretization schemes (second-order upwind in Fluent vs. hybrid in STAR-CCM+). This slight discrepancy (30%) can be attributed to inherent differences in the numerical schemes and turbulence models of the two solvers. Nevertheless, the close agreement in both the order of magnitude and the qualitative trends shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 confirms the robustness of the steady-state simulation results. The peak oxygen concentration at the interface (∼

wt%) lies within a controlled range, supporting protective oxide stability without exceeding solubility limits. We relocate this rationale earlier (boundary condition justification) to emphasize that CFD resolves spatial gradients and transient equilibration times beyond thermodynamic bounds alone.

3.3. Transient Dynamics and Parametric Study

Beyond the steady-state behavior, transient simulations were performed to investigate the dynamic evolution of oxygen concentration and to evaluate the system’s response to variations in key operational parameters, such as inlet velocity and temperature. All transient cases assumed that initially the liquid alloy contains a uniform dissolved oxygen content of

wt% (i.e., essentially oxygen-starved), and at time

the gas-phase oxygen source at the interface is activated (providing a fixed equilibrium concentration at the boundary). The simulations were run with a time step of 0.05 s up to a physical time of 150 s, which is sufficient for the system to approach steady state.

Figure 9 plots the oxygen content as a function of time at several representative locations (Points 1–6) in the LBE domain. In general, we observe that regions closer to the interface respond the fastest to the imposed oxygen supply, while regions farther downstream or deeper in the liquid respond more slowly. For example, the probe near the interface close to the inlet (Point 1) shows a rapid rise in oxygen concentration shortly after

, as convection quickly carries oxygenated fluid from the interface into this region. In contrast, a probe located near the outlet (Point 5 or Point 6) exhibits a noticeable time lag before the oxygen level starts to increase, indicating that oxygen must first be transported from the interface to that far end of the loop. Eventually, however, all monitoring points asymptotically approach constant values, signifying that a new equilibrium has been reached in the loop. By roughly 150 s, the spatial distribution of oxygen stabilizes and matches the steady-state profile discussed earlier. This transient behavior highlights the interplay between convection and diffusion in the system: convection carries oxygen-laden fluid away from the interface, while diffusion slowly spreads oxygen into regions that the bulk flow may not immediately reach. Without any flow (a purely stagnant case), oxygen would rely solely on molecular diffusion and would take an exceedingly long time to penetrate the LBE coolant [

23]. In our dynamic flow scenario, however, the presence of circulation reduces the characteristic oxygen transport time from the order of weeks (for pure diffusion over centimeter scales) to the order of tens of seconds, illustrating the dramatic improvement in oxygen delivery achieved by active flow.

Five different inlet flow velocities (0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 0.9, and 1.1 m/s) were tested to evaluate how flow rate influences oxygen transport, as illustrated in

Table 11. The resulting oxygen concentration fields and time histories indicate a non-monotonic dependence on flow velocity. As the inlet velocity increases from the lowest value, the overall oxygen level in the LBE initially increases, reaching a maximum around an intermediate velocity (0.7–0.9 m/s), and then decreases slightly at the highest velocity tested. This trend can be understood by considering the competing effects of convective mixing versus residence time. At low flow speeds, the LBE spends a long time at the interface (high residence time), which is favorable for oxygen uptake; however, the convective transport is weak, so oxygen tends to accumulate only near the interface and does not disperse efficiently through the bulk. This leads to lower oxygen delivery to the outlet despite the long contact time. As the flow rate increases, convection becomes more vigorous and can carry oxygen deeper into the fluid and toward the outlet—effectively enhancing mass transfer by thinning the diffusion boundary layer and renewing low-oxygen liquid at the interface [

23]. Up to a point, a faster flow thus improves the oxygen absorption per cycle. However, beyond the optimal point, if the flow is too fast, the time each fluid element spends in contact with the interface is shortened so much that the liquid leaves the oxygen source region before it can uptake sufficient oxygen. In that extreme, the oxygen content of the outflow can actually drop slightly, as observed at 1.1 m/s.

Table 11 shows the spatial distributions of oxygen concentration and velocity for each tested flow rate, clearly demonstrating how the concentration field evolves from a highly stratified pattern at low velocities to a more uniform distribution at intermediate velocities, before the residence time limitation becomes dominant at the highest velocity. In our simulations, the peak oxygen concentration at the outlet was achieved at an intermediate velocity, indicating an optimal balance between mixing intensity and exposure time. Importantly, the velocity field for all cases remained qualitatively similar (all were turbulent flows with a Reynolds number on the order of

in the inlet pipe). Higher inlet velocity simply produced higher turbulence kinetic energy and flatter velocity profiles in the bulk, which improved oxygen dispersion. The positive correlation between flow rate and oxygen transfer (up to the optimum) is consistent with findings from other researchers [

22]. This refinement highlights a velocity window rather than monotonic increase, informing operational setpoint selection.

The influence of temperature on oxygen diffusion was examined by varying the LBE inlet temperature from 573 K up to 823 K (in six increments) while keeping the inlet flow rate constant, as summarized in

Table 12. Temperature affects two critical parameters in the simulations: (i) the equilibrium oxygen concentration at the gas–liquid interface through the temperature-dependent solubility Equation (

7) and (ii) the oxygen diffusion coefficient Equation (

9). Both parameters increase with temperature, thereby enhancing oxygen transport. In contrast to flow rate, the oxygen uptake showed a monotonic trend with temperature. Higher temperatures led to universally higher oxygen concentrations throughout the LBE. The temperature-dependent solubility Equation (

7) governs the equilibrium interfacial concentration

, which increases with temperature and enlarges the concentration driving force for mass transfer. At 823 K, the outlet oxygen concentration and overall oxygen distribution were significantly greater than those at 573 K, indicating that elevated temperature facilitates oxygen diffusion. This behavior is expected because increasing temperature raises both molecular diffusivity and equilibrium solubility. As shown in

Table 12, the oxygen concentration fields exhibit progressively higher penetration depths and stronger gradients as temperature increases, while the velocity field remains virtually unchanged across all temperature cases.

The temporal evolution of oxygen concentration at different spatial locations under varying temperature conditions is presented in

Figure 10. These time-series measurements reveal how temperature influences both the rate of oxygen uptake and the final steady-state concentrations achieved at each monitoring point. At lower temperatures (573 K), the oxygen concentration rises more gradually and plateaus at lower levels, reflecting the combined effects of reduced interfacial equilibrium concentration and slower diffusion kinetics. Conversely, at higher temperatures (823 K), all monitoring points exhibit steeper initial rise rates and achieve significantly higher asymptotic values, demonstrating enhanced oxygen transport efficiency.

The flow pattern and velocity magnitude are imposed by the pump (inlet boundary condition) and geometry, so changing the fluid temperature had a negligible effect on the hydrodynamics in our model. There may be minor changes in fluid properties (e.g., viscosity decreases with temperature, which could slightly increase the Reynolds number for the same mass flow rate), but within this temperature range those changes did not produce any noticeable alteration in the flow structure. Thus, we can isolate the temperature effect on oxygen transport as purely a diffusion/solubility effect rather than a flow effect. The outcome reinforces that higher coolant temperatures promote oxygen diffusion and could be used to improve oxygenation efficiency if the material constraints allow. This trend aligns with experimental and modeling observations that mass transfer coefficients for oxygen increase with temperature in LBE systems [

23]. It also implies that in a real reactor system, oxygen control might become more challenging at lower temperatures (due to sluggish diffusion), whereas at higher operating temperatures the oxygen distribution can equilibrate more quickly—albeit at the risk of exceeding solubility limits if not carefully controlled.

It should be noted that in all the parametric cases above, the initial dissolved oxygen in the LBE was set very low (

wt%). This represents a conservative scenario with the maximum driving force for oxygen absorption. The literature suggests that starting from such a low oxygen baseline yields a slightly higher effective mass transfer rate, whereas if the bulk fluid already contains more oxygen, the relative gain (and the mass transfer coefficient) would be smaller [

22]. In our study, the initial condition ensures the worst case (highest gradient) for oxygen diffusion, which is appropriate for designing control systems, since any pre-oxygenation of the coolant would only make the mass transfer easier. Meanwhile, the gas-phase oxygen concentration (and thus the interface equilibrium concentration) was kept constant in each case; prior studies indicate that once the interface is maintained at saturation, further increasing the oxygen partial pressure in the cover gas has a minimal effect on the mass transfer coefficient [

22]. This justifies our approach of using a fixed equilibrium boundary condition—it captures the physics without needing to model the gas phase in detail.