Covalent Arabinoxylans Nanoparticles Enable Oral Insulin Delivery and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cross-Linking Process

2.2. Phenolic Acid Analysis

2.3. Nanoparticle Fabrication

2.4. Characterization of Nanoparticles

2.5. Bioassay

2.6. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.6.1. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.6.2. Sequence Data Preprocessing and Diversity Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Cross-Linking Process

3.2. Phenolic Acid Analysis

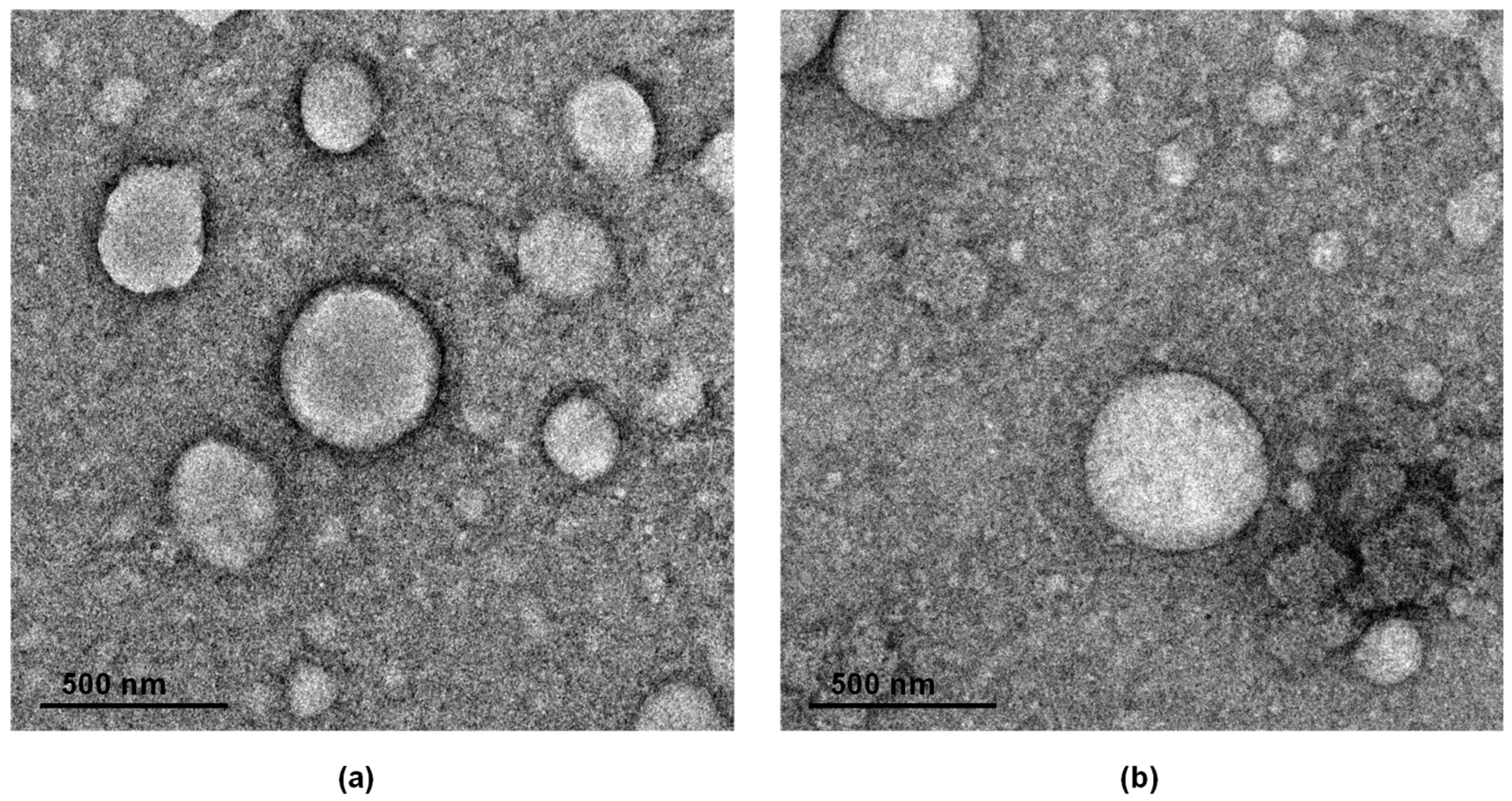

3.3. Nanoparticle Fabrication and Characterization

3.4. Bioassay

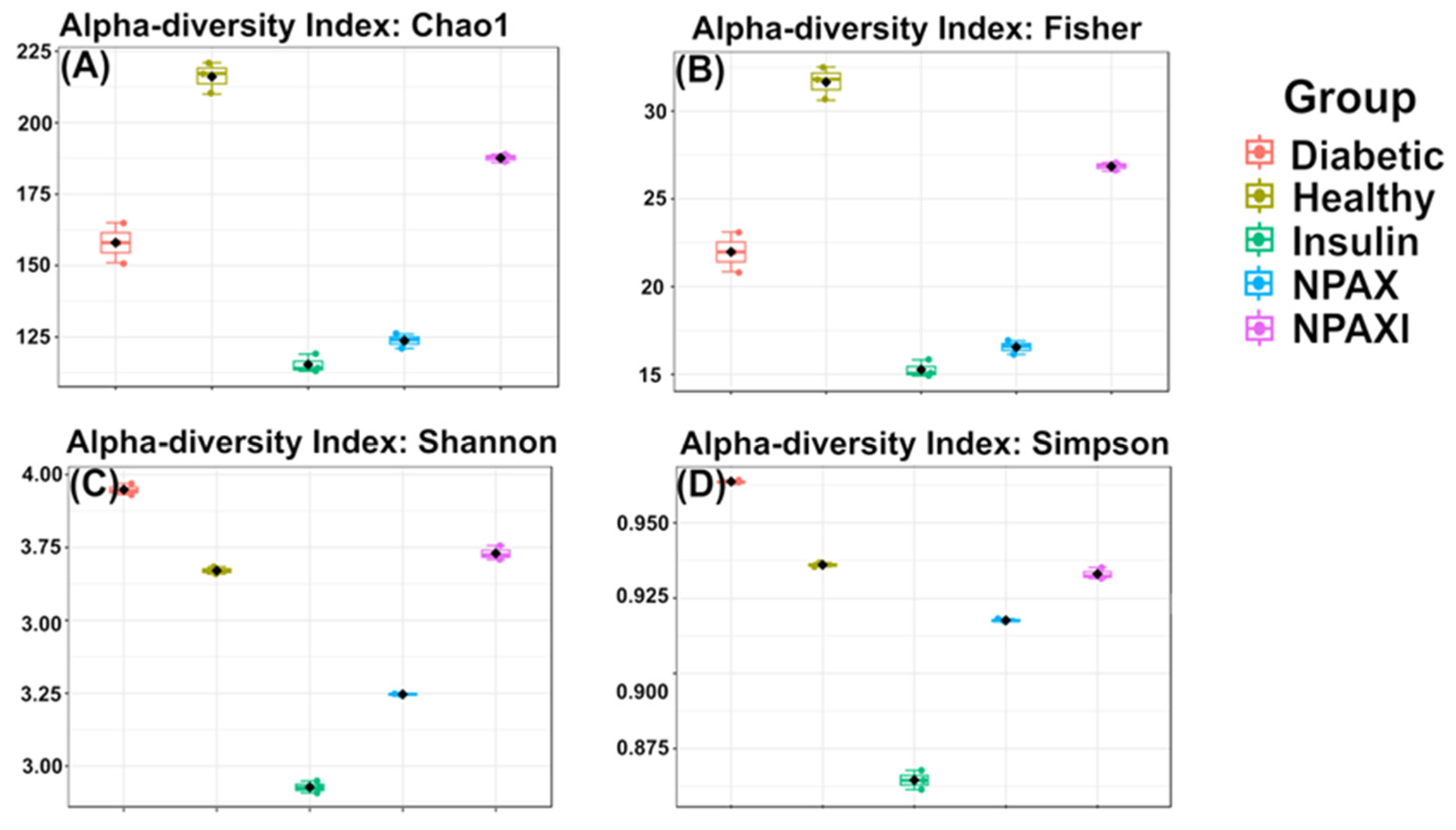

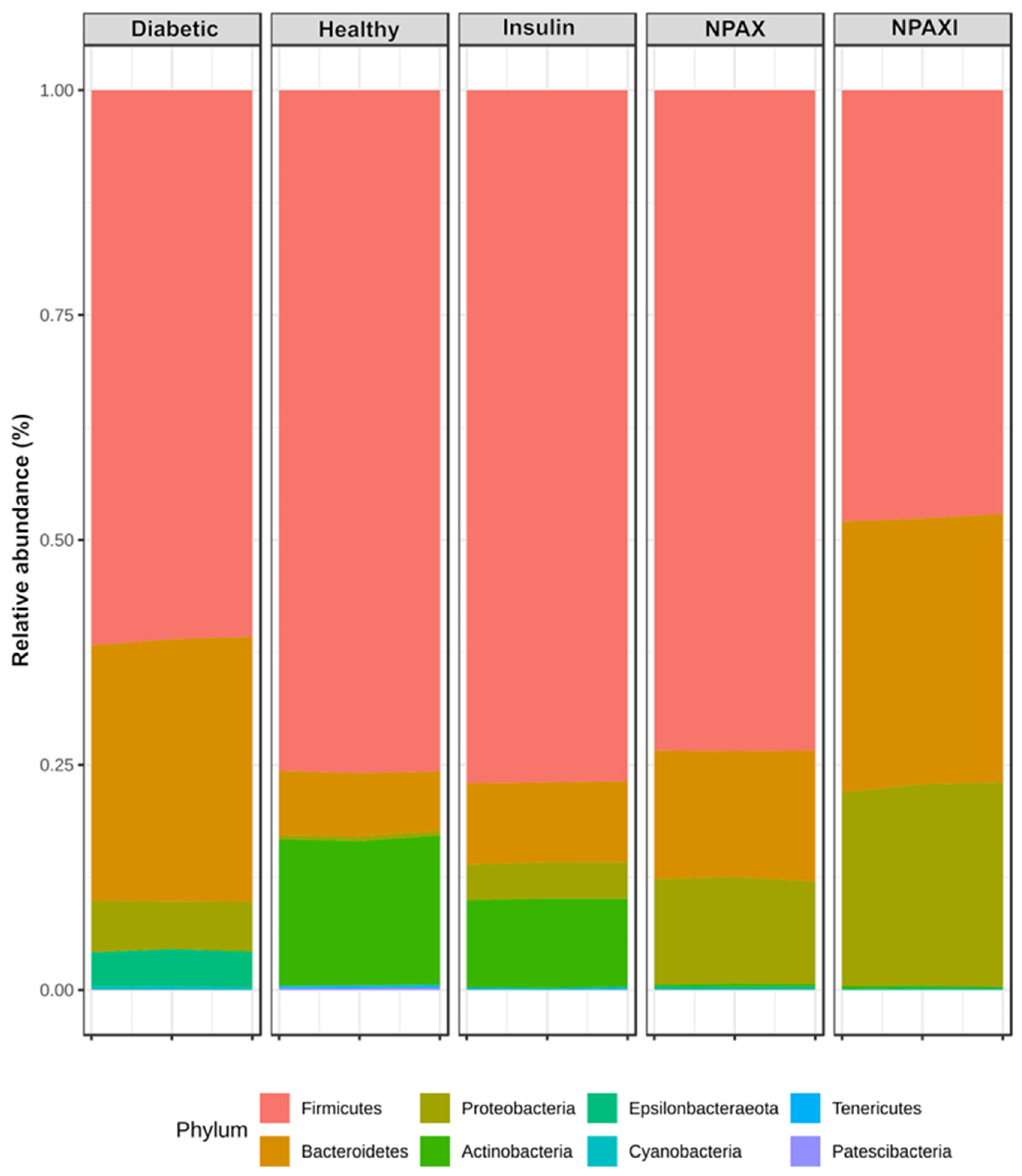

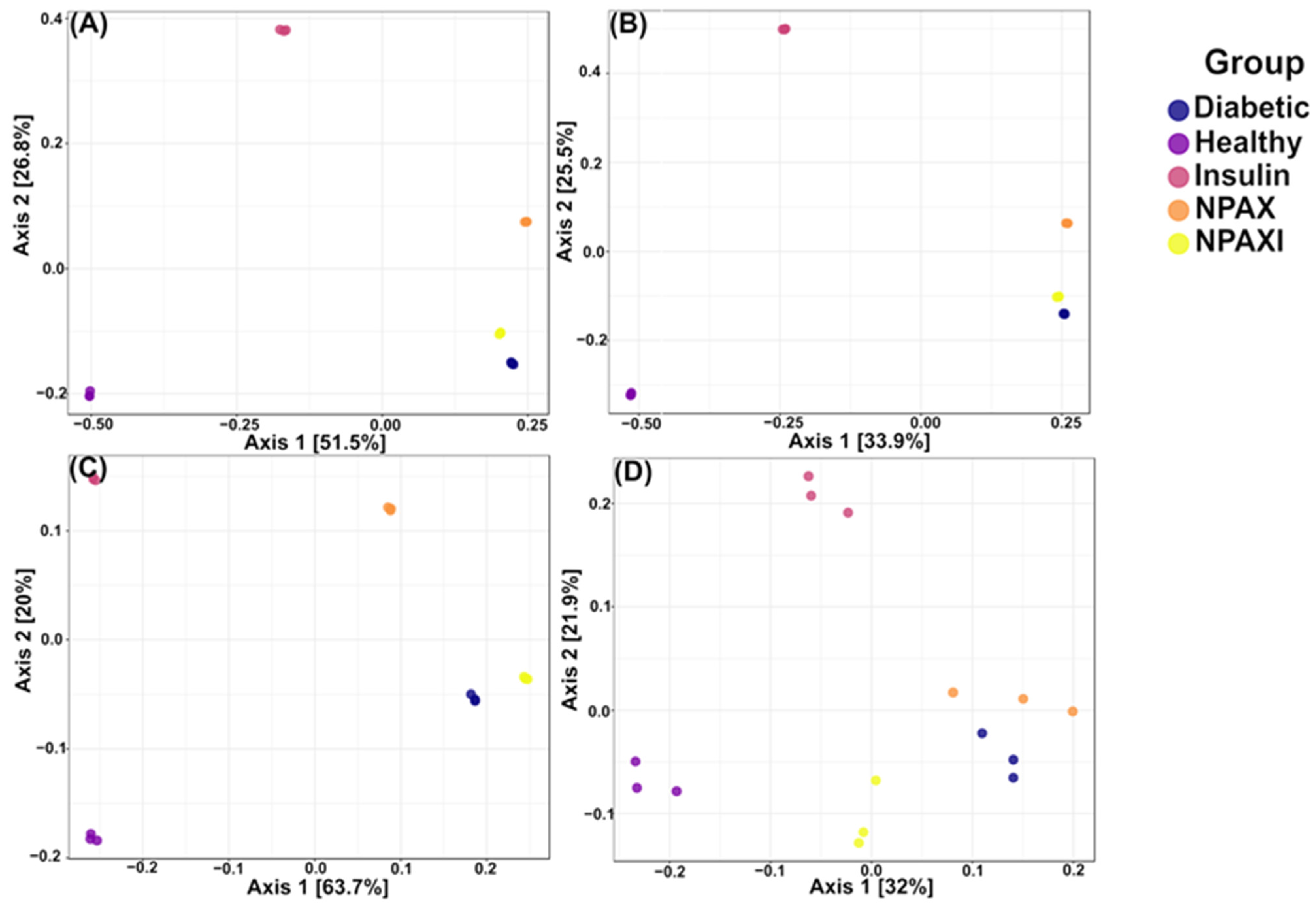

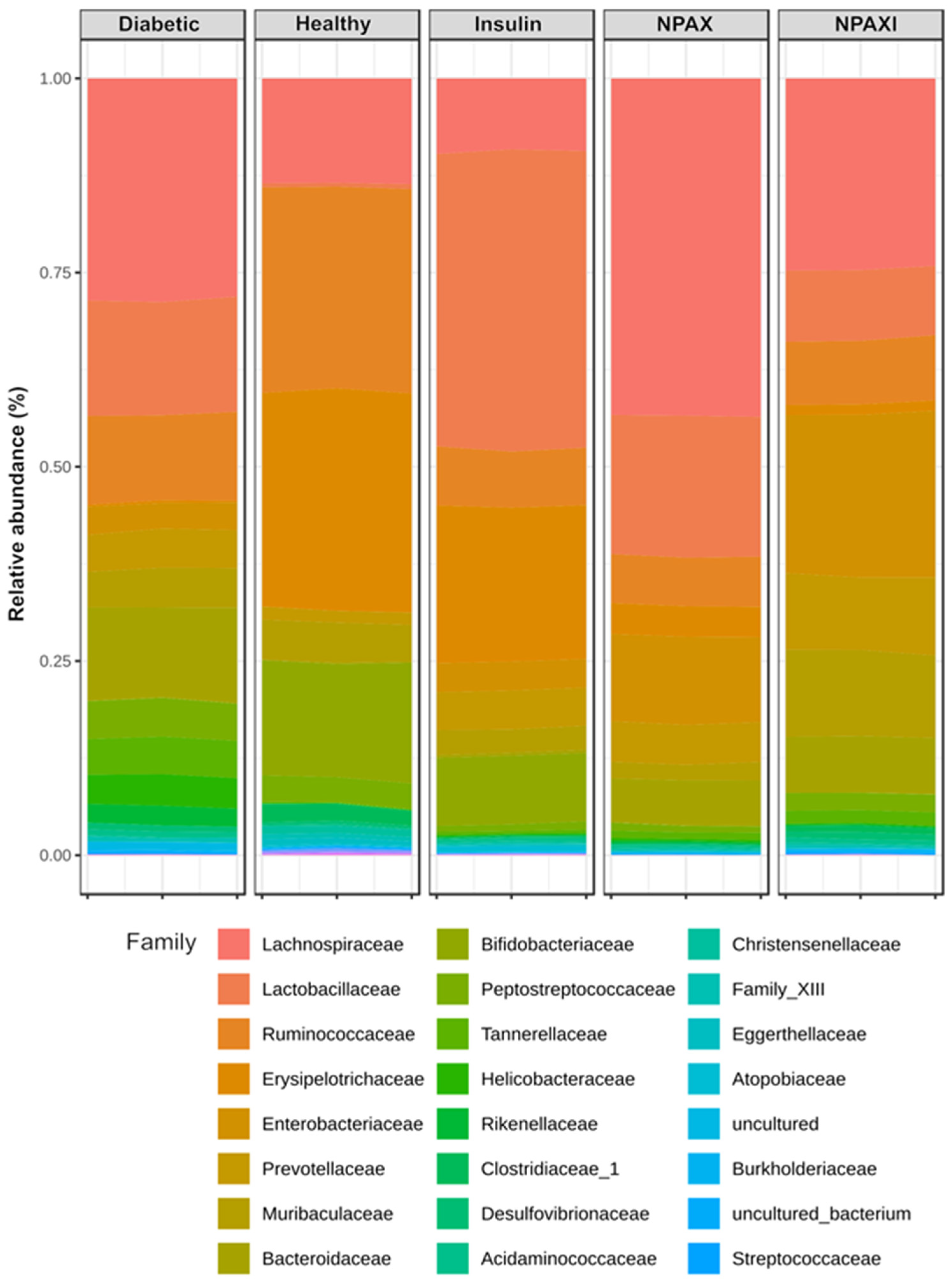

3.5. Gut Microbiota Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública (INSP). Prevalencia de Prediabetes y Diabetes En México: Ensanut. 2022. Available online: https://www.insp.mx/avisos/prevalencia-de-prediabetes-y-diabetes-en-mexico-ensanut-2022 (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Magliano, D.J.; Boyko, E.J.; Genitsaridi, I.; Piemonte, L.; Riley, P.; Salpea, P. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 11th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Souto, E.B.; Souto, S.B.; Campos, J.R.; Severino, P.; Pashirova, T.N.; Zakharova, L.Y.; Silva, A.M.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Izzo, A.A.; et al. Nanoparticle delivery systems in the treatment of diabetes complications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, C.Y.; Gan, W.L.; Lai, S.J.; Tam, R.S.M.; Tan, J.F.; Dietl, S.; Chuah, L.H.; Voelcker, N.; Bakhtiar, A. Critical updates on oral insulin drug delivery systems for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaklotar, D.; Agrawal, P.; Abdulla, A.; Singh, R.P.; Mehata, A.K.; Singh, S.; Mishra, B.; Pandey, B.L.; Trigunayat, A.; Muthu, M.S. Transition from passive to active targeting of oral insulin nanomedicines: Enhancement in bioavailability and glycemic control in diabetes. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 1465–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, S.; Chandran, S.V.; Selvamurugan, N.; Nazeer, R.A. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of thiolated chitosan nanoparticles for oral delivery of insulin in vivo. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyam, S.; Choukaife, H.; Al Rahal, O.; Alfatama, M. Colonic targeting insulin-loaded trimethyl chitosan nanoparticles coated pectin for oral delivery: In Vitro and In Vivo studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, H.; Moustafa, N.; Ahmed, R.R.; El-Shahawy, A.A.G.; Eldin, Z.E.; Al-Jameel, S.S.; Amin, K.A.; Ahmed, O.M.; Abdul-Hamid, M. Therapeutic effect of oral insulin-chitosan nanobeads pectin-dextrin shell on streptozotocin-diabetic male albino rats. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Millan, E.; Landillon, V.; Morel, M.-H.; Rouau, X.; Doublier, J.-L.; Micard, V. Arabinoxylan gels: Impact of the feruloylation degree on their structure and properties. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhong, W.; Su, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, S.; Lu, X.; Qin, W. Hydrogel formation of enzymatically solubilized corn bran feruloylated arabinoxylan by laccase-catalyzed cross-linking. Foods 2025, 14, 2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Millan, E.; Vargas-Albores, F.; Fierro-Islas, J.M.; Gollas-Galván, T.; Magdaleno-Moncayo, D.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Martínez-Porchas, M.; Lago-Lestón, A. Arabinoxylans and gelled arabinoxylans used as anti-obesogenic agents could protect the stability of intestinal microbiota of rats consuming high-fat diets. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 71, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudan, S.; Ishibashi, R.; Nishikawa, M.; Tabuchi, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Ikushiro, S.; Furusawa, Y. Effect of wheat-derived arabinoxylan on the gut microbiota composition and colonic regulatory T cells. Molecules 2023, 28, 3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, H.; Iftikhar, A.; Muzaffar, H.; Almatroudi, A.; Allemailem, K.S.; Navaid, S.; Saleem, S.; Khurshid, M. Biodiversity of gut microbiota: Impact of various host and environmental factors. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5575245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckburg, P.B.; Bik, E.M.; Bernstein, C.N.; Purdom, E.; Dethlefsen, L.; Sargent, M.; Gill, S.R.; Nelson, K.E.; Relman, D.A. Diversity of the Human Intestinal Microbial Flora. Science 2005, 308, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, M.; Li, Z.; You, H.; Rodrigues, R.; Jump, D.B.; Morgun, A.; Shulzhenko, N. Role of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology. EBioMedicine 2020, 51, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huttenhower, C.; Gevers, D.; Knight, R.; Abubucker, S.; Badger, J.H.; Chinwalla, A.T.; Creasy, H.H.; Earl, A.M.; Fitzgerald, M.G.; Fulton, R.S.; et al. The Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasain, Z.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Kamaruddin, N.A.; Mohamed Ismail, N.A.; Razalli, N.H.; Gnanou, J.V.; Raja Ali, R.A. Gut microbiota and gestational diabetes mellitus: A review of host-gut microbiota interactions and their therapeutic potential. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, N.; Vogensen, F.K.; Van Den Berg, F.W.J.; Nielsen, D.S.; Andreasen, A.S.; Pedersen, B.K.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Sørensen, S.J.; Hansen, L.H.; Jakobsen, M. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, Z.C.; Villa, M.M.; Durand, H.K.; Jiang, S.; Dallow, E.P.; Petrone, B.L.; Silverman, J.D.; Lin, P.H.; David, L.A. Microbiota responses to different prebiotics are conserved within individuals and associated with habitual fiber intake. Microbiome 2022, 10, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Fan, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, P.; Chang, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, L.; Yin, Q. Effects of physicochemical and biological treatment on structure, functional and prebiotic properties of dietary fiber from corn straw. Foods 2024, 13, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, E.S.V.; Lima, G.C.; Naves, M.M.V. Dietary fibers as beneficial microbiota modulators: A proposed classification by prebiotic categories. Nutrition 2021, 89, 111217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas Pedrosa, L.; de Vos, P.; Fabi, J.P. From structure to function: How prebiotic diversity shapes gut integrity and immune balance. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Hu, J.; Chen, H.; Geng, F.; Nie, S. Arabinoxylan ameliorates type 2 diabetes by regulating the gut microbiota and metabolites. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schupfer, E.; Pak, S.C.; Wang, S.; Micalos, P.S.; Jeffries, T.; Ooi, S.L.; Golombick, T.; Harris, G.; El-Omar, E. The effects and benefits of arabinoxylans on human gut microbiota—A narrative review. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Hu, J.; Gao, H.; Li, M.; Sun, Y.; Chen, H.; Zuo, S.; Fang, Q.; Huang, X.; Yin, J.; et al. Bioactive dietary fibers selectively promote gut microbiota to exert antidiabetic effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7000–7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. GRN No. 1073 Corn Bran Arabinoxylan. 2022. Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=1073 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Izydorczyk, M.S.; Biliaderis, C.G. Cereal arabinoxylans: Advances in structure and physicochemical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 1995, 28, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.J.; Qiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Ou, X.; Wang, X. Isolation, structural, functional, and bioactive properties of cereal arabinoxylan—A critical review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 15437–15457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elschner, T.; Fischer, S. Reconsidering the feruoylation of arabinoxylan by Mitsunobu reaction with a di-arabinofuranosyl-xylotriose model. Cellulose 2023, 30, 7389–7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, A.L.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Micard, V.; Rascón-Chu, A.; Brown-Bojorquez, F.; Sotelo-Cruz, N.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J. In vitro degradation of covalently cross-linked arabinoxylan hydrogels by bifidobacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 144, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Encinas, M.A.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Astiazaran-Garcia, H.F.; Valencia-Rivera, D.E. Ferulated arabinoxylans and their gels: Functional properties and potential application as antioxidant and anticancer agent. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 2314759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, A.L.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Sotelo-Cruz, N.; Micard, V.; Rascón-Chu, A.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Canett-Romero, R. Enzymatically cross-linked arabinoxylan microspheres as oral insulin delivery system. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Burgos, A.M.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Rascón-Chu, A.; Martínez-López, A.L.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Brown-Bojorquez, F. Tailoring reversible insulin aggregates loaded in electrosprayed arabinoxylan microspheres intended for colon-targeted delivery. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Samaniego, R.; Rascón-Chu, A.; Brown-Bojorquez, F.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Pedroza-Montero, M.; Silva-Campa, E.; Sotelo-Cruz, N.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J. Electrospray- assisted fabrication of core-shell arabinoxylan gel particles for insulin and probiotics entrapment. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astiazarán-Rascón, I. Obtención y Caracterización Parcial de Nanopartículas de Arabinoxilanos Cargadas con Insulina. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Sonora, Hermosillo, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal-Millan, E.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Morales-Burgos, A.M.; Campa-Mada, A.C.; Martinez-Robinson, K.G.; Marquez-Escalante, J.A.; Toledo-Guillen, A.R. Method for Obtaining Functionalized Arabinoxylans to Form Covalent Gelled Nanoparticles and Enhance Beneficial Health Effects. Mexican Patent 392,415, 28 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Encinas, M.A.; Valencia-Rivera, D.E.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Astiazaran-Garcia, H.; Micard, V.; Rascón-Chu, A. Fermentation of ferulated arabinoxylan recovered from the maize bioethanol industry. Processes 2021, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Anda-Flores, Y.B.; Carvajal-Millán, E.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Rascón-Chu, A.; Martinez-López, A.L.; Marquez-Escalante, J.A.; Brown, F.; Tánori-Córdova, J.C. Covalently cross-linked nanoparticles based on ferulated arabinoxylans recovered from a distiller’s dried grains byproduct. Processes 2020, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Anda-Flores, Y.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Tanori-Cordova, J.; Martínez-López, A.L.; Burgara-Estrella, A.J.; Pedroza-Montero, M.R. Conformational behavior, topographical features, and antioxidant activity of partly de-esterified arabinoxylans. Polymers 2021, 13, 2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, E.; Babot, C.; Rouau, X.; Micard, V. Oxidative gelation of feruloylated arabinoxylan as affected by protein. Influence on protein enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2004, 18, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-062-ZOO-1999; Especificaciones Técnicas Para La Producción, Cuidado y Uso de Los Animales de Laboratorio. NOM Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación: Mexico City, Mexico, 1999.

- Martínez-López, A.L.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Sotelo-Cruz, N.; Micard, V.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Prakash, S.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Cannet-Romero, R.; Toledo-Guillén, A.R. Biodegradable Covalent Matrices for Insulin Delivery by Oral Route Directed to the Colon Activated by the Microbiota and Process for its Obtaining. European Patent EP3666264, 29 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-López, A.L.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Canett-Romero, R.; Prakash, S.; Rascón-Chu, A.; López-Franco, Y.L.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Micard, V. Arabinoxylans-based oral insulin delivery system targeting the colon: Simulation in a human intestinal microbial ecosystem and evaluation in diabetic rats. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree 2—Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.; Liu, P.; Zhou, G.; Xia, J. Using MicrobiomeAnalyst for comprehensive statistical, functional, and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 799–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhariwal, A.; Chong, J.; Habib, S.; King, I.L.; Agellon, L.B.; Xia, J. MicrobiomeAnalyst: A web-based tool for comprehensive statistical, visual and meta-analysis of microbiome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W180–W188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niño-Medina, G.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Marquez-Escalante, J.A.; Guerrero, V.; Salas-Muñoz, E. Feruloylated arabinoxylans and arabinoxylan gels: Structure, sources and applications. Phytochem. Rev. 2010, 9, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doublier, J.-L.; Garnier, C.; Cuvelier, G. Gums and Hydrocolloids: Functional Aspects. In Carbohydrates in Food, 3rd ed.; Eliasson, A.-C., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 285–332. [Google Scholar]

- Ow, V.; Lin, Q.; Wong, J.H.M.; Sim, B.; Tan, Y.L.; Leow, Y.; Goh, R.; Loh, X.J. Understanding the interplay between pH and charges for theranostic nanomaterials. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 6960–6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendayan, M.; Ziv, E.; Gingras, D.; Ben-Sasson, R.; Bar-On, H.; Kidron, M. Biochemical and morpho-cytochemical evidence for the intestinal absorption of insulin in control and diabetic rats. Comparison between the effectiveness of duodenal and colon mucosa. Diabetologia 1994, 37, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Anda-Flores, Y.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Campa-Mada, A.C.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Tanori-Cordova, J.; Martínez-López, A.L. Polysaccharide-based nanoparticles for colon-targeted drug delivery systems. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 626–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, N.; Schreiner, J.; Baur, F.; Vogel-Kindgen, S.; Windbergs, M. Predicting nanocarrier permeation across the human intestine in vitro: Model matters. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 5775–5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B.L. Streptozotocin -induced diabetic models in mice and rats. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinna, N.A.; Badwan, A.A. Impact of streptozotocin on altering normal glucose homeostasis during insulin testing in diabetic rats compared to normoglycemic rats. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2015, 9, 2515–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.L.; Kiersgaard, M.K.; Sørensen, D.B.; Mikkelsen, L.F. Fasting of mice: A review. Lab. Anim. 2013, 47, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.D.; Maratou, E.; Kountouri, A.; Board, M.; Lambadiari, V. Regulation of postabsorptive and postprandial glucose metabolism by insulin-dependent and insulin-independent mechanisms: An integrative approach. Nutrients 2021, 13, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, B.; Chou, M.C.Y.; Field, J.B. Time-action characteristics of regular and NPH insulin in insulin-treated diabetics. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1980, 50, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, I.B.; Juneja, R.; Beals, J.M.; Antalis, C.J.; Wright, E.E. The evolution of insulin and how it informs therapy and treatment choices. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 733–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.R.M.K.; Dkhar, S.A.; Ramaswamy, S.; Naveen, A.T.; Shewade, D.G. An inherent acceleratory effect of insulin on small intestinal transit and its pharmacological characterization in normal mice. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 2593–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rains, J.L.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative stress, insulin signaling, and diabetes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 50, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X. Gut Microbiota alteration is associated with cognitive deficits in genetically diabetic (Db/db) mice during aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 13, 815562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, H.; Yao, M.; Cao, L.; Sferra, T.J.; Ke, X.; Peng, J.; Shen, A. Qing Hua Chang Yin alleviates chronic colitis of mice by protecting intestinal barrier function and improving colonic microflora. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1176579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Huang, F.; Shen, G.X. Dose-responses relationship in glucose lowering and gut dysbiosis to Saskatoon berry powder supplementation in high fat-high sucrose diet-induced insulin resistant mice. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, B.A.; O’Hara, C.; Wu, L.; El-Rassi, G.D.; Ritchey, J.W.; Chowanadisai, W.; Lin, D.; Smith, B.J.; Lucas, E.A. Wheat germ supplementation increases Lactobacillaceae and promotes an anti-inflammatory gut milieu in C57BL/6 mice fed a high-fat, high-sucrose diet. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, V.; Scaldaferri, F.; Putignani, L.; Del Chierico, F. The role of Enterobacteriaceae in gut microbiota dysbiosis in inflammatory bowel diseases. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Xu, X.; He, Z.; Li, N.; Ouyang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, N.; He, C. Helicobacter pylori infection worsens impaired glucose regulation in high-fat diet mice in association with an altered gut microbiome and metabolome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 2081–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cross-Linking Structure | Content (µg/mg) | |

|---|---|---|

| NPAX | NPAXI | |

| Dimers of ferulic acid isomers (di-FA) | ||

| 8-5′ | 1.10 ± 0.12 a | 1.39 ± 0.08 a |

| 8-O-4′ | 0.22 ± 0.04 a | 0.28 ± 0.03 a |

| 5-5′ | 0.17 ± 0.03 a | 0.24 ± 0.04 a |

| Total of di-FA | 1.49 ± 0.32 b | 1.91 ± 0.05 a |

| Trimer of ferulic acid (tri-FA) | 0.31 ± 0.07 b | 0.42 ± 0.04 a |

| Material | Size Range (nm) | Polydispersity Index Range (%) | Zeta Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPAX | 346–1115 | 12–198 | −41 ± 5 a |

| NPAXI | 191–1131 | 12–220 | −31 ± 7 a |

| Pair Comparison | Chao1 | Fisher | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy vs. Diabetic | 4.628 × 10−4 | 4.0396 × 10−4 | 1.0427 × 10−4 | 4.0617 × 10−6 |

| Healthy vs. Insulin | 7.0322 × 10−5 | 1.2223 × 10−4 | 6.3367 × 10−6 | 3.9715 × 10−4 |

| Healthy vs. NPAX | 7.0322 × 10−5 | 3.1141 × 10−4 | 2.5006 × 10−4 | 9.646 × 10−6 |

| Healthy vs. NPAXI | 7.0322 × 10−5 | 0.0091612 | 0.034011 | 0.10046 |

| Diabetic vs. Insulin | 0.0031449 | 0.0091612 | 4.3355 × 10−7 | 2.774 × 10−4 |

| Diabetic vs. NPAX | 0.0075845 | 0.0091612 | 2.4175 × 10−4 | 2.8435× 10−8 |

| Diabetic vs. NPAXI | 0.014702 | 0.0091612 | 3.5553 × 10−4 | 8.4495 × 10−4 |

| Insulin vs. NPAX | 0.02644 | 0.026195 | 0.0013696 | 9.6871 × 10−4 |

| Insulin vs. NPAXI | 7.3359 × 10−5 | 4.5554 × 10−5 | 2.2479 × 10−6 | 3.2062 × 10−5 |

| NPAX vs. NPAXI | 1.8496 × 10−5 | 1.1479 × 10−5 | 8.2555 × 10−4 | 0.0035253 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

De Anda-Flores, Y.B.; Carvajal-Millan, E.; Martínez-Porchas, M.; Rascon-Chu, A.; Martinez-Robinson, K.G.; Lizardi Mendoza, J.; Tanori-Cordova, J.; Martínez-López, A.L.; Garibay-Valdez, E.; Mendez-Romero, J.I. Covalent Arabinoxylans Nanoparticles Enable Oral Insulin Delivery and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Diabetes. Polysaccharides 2026, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010003

De Anda-Flores YB, Carvajal-Millan E, Martínez-Porchas M, Rascon-Chu A, Martinez-Robinson KG, Lizardi Mendoza J, Tanori-Cordova J, Martínez-López AL, Garibay-Valdez E, Mendez-Romero JI. Covalent Arabinoxylans Nanoparticles Enable Oral Insulin Delivery and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Diabetes. Polysaccharides. 2026; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Anda-Flores, Yubia Berenice, Elizabeth Carvajal-Millan, Marcel Martínez-Porchas, Agustin Rascon-Chu, Karla G. Martinez-Robinson, Jaime Lizardi Mendoza, Judith Tanori-Cordova, Ana Luisa Martínez-López, Estefanía Garibay-Valdez, and José Isidro Mendez-Romero. 2026. "Covalent Arabinoxylans Nanoparticles Enable Oral Insulin Delivery and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Diabetes" Polysaccharides 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010003

APA StyleDe Anda-Flores, Y. B., Carvajal-Millan, E., Martínez-Porchas, M., Rascon-Chu, A., Martinez-Robinson, K. G., Lizardi Mendoza, J., Tanori-Cordova, J., Martínez-López, A. L., Garibay-Valdez, E., & Mendez-Romero, J. I. (2026). Covalent Arabinoxylans Nanoparticles Enable Oral Insulin Delivery and Gut Microbiota Modulation in Diabetes. Polysaccharides, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides7010003