Sustainable Production of Chitin from Supercritical CO2 Defatted Domestic Cricket (Acheta domesticus L.) Meal: One-Pot Preparation, Characterization, and Effects of Different Deep Eutectic Solvents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Obtaining Domestic Cricket Meal

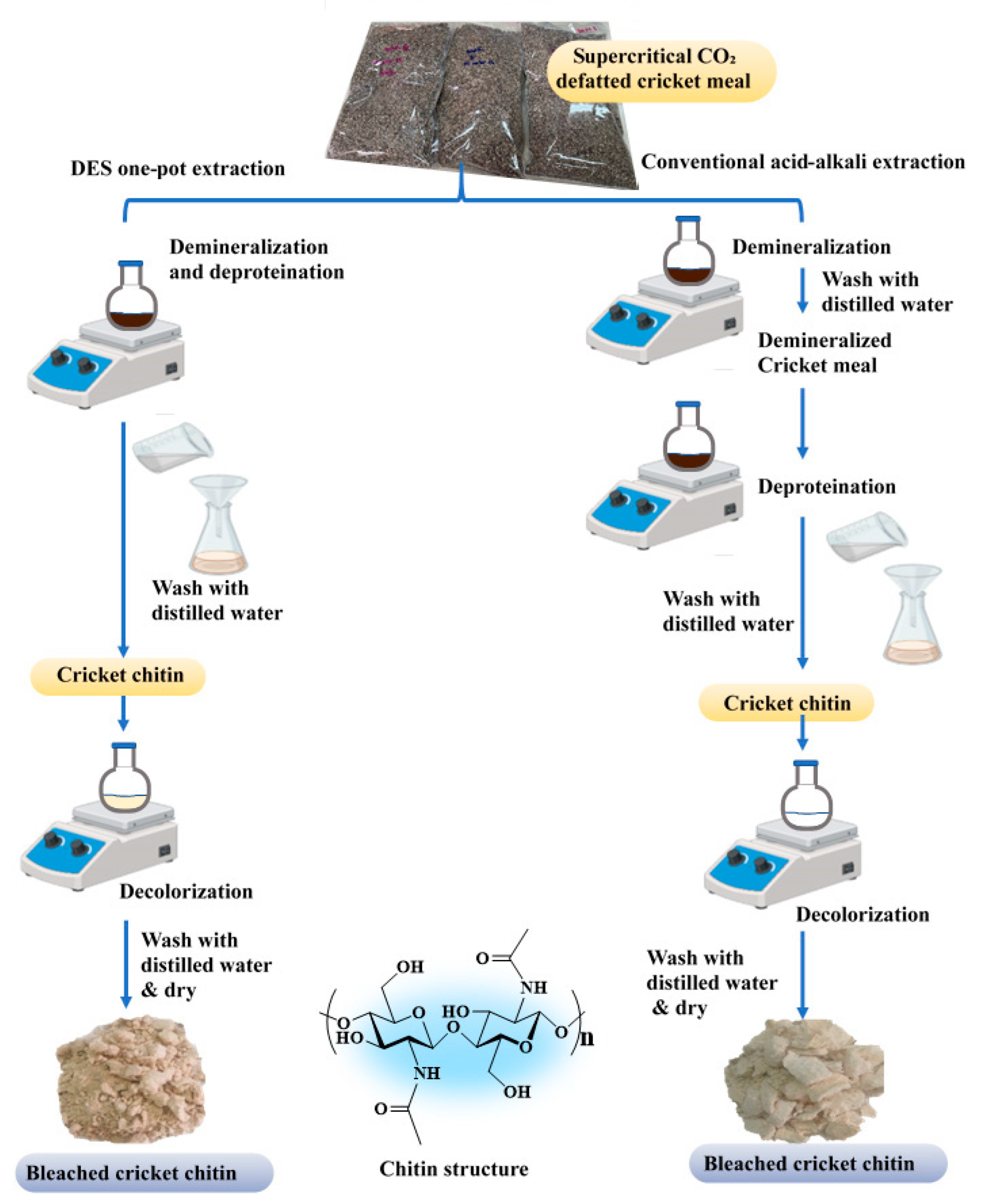

2.3. Preparation of Cricket Chitin

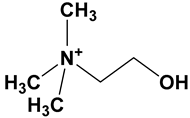

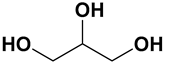

2.3.1. Preparation of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs)

2.3.2. Extraction of Cricket Chitin

2.3.3. Recovery of Deep Eutectic Solvents

2.3.4. Preparation of Chitin by Conventional Extraction

2.4. Chemical Composition Analysis of Cricket Chitin

2.4.1. Moisture Content

2.4.2. Ash Content

2.4.3. Protein Content

2.5. Evaluation of Chitin Yield and Purity

2.6. Determination of Physical Characterization of Cricket Chitin

2.6.1. Colorimetric Analysis

2.6.2. FTIR Analysis

2.6.3. X-Ray Diffraction

2.6.4. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Analysis

2.6.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preparation of Cricket Protein from Cricket Powder

3.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Cricket Chitin

3.2.1. Physical Appearance of Cricket Chitin

3.2.2. FTIR Analysis of Domestic Cricket Chitin

3.2.3. XRD Analysis of Domestic Cricket Chitin

3.2.4. XPS Analysis

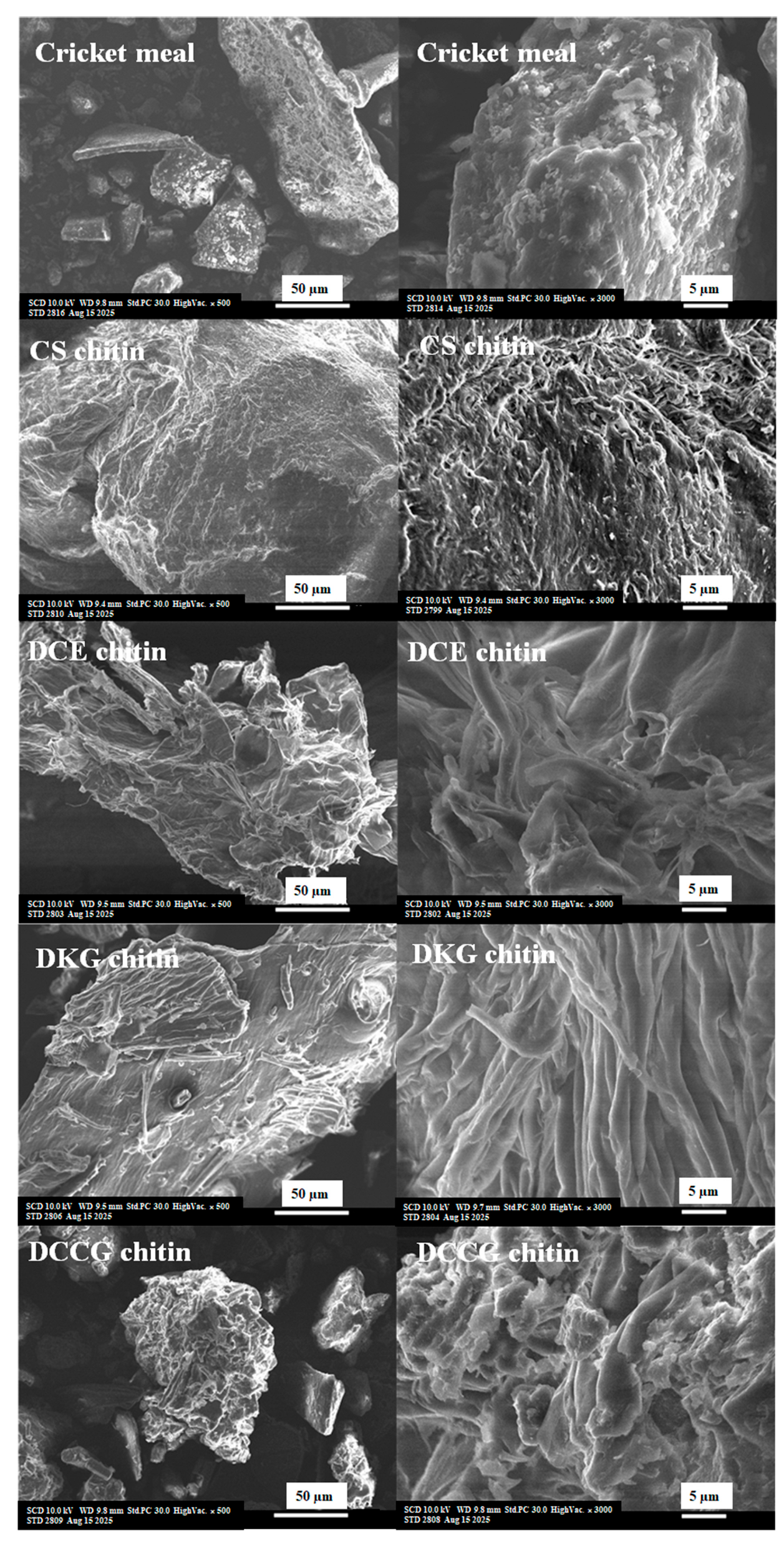

3.3. Microstructure Morphology of Cricket Chitin

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elouali, S.; Ait Hamdan, Y.; Benali, S.; Lhomme, P.; Gosselin, M.; Raquez, J.-M.; Rhazi, M. Extraction of Chitin and Chitosan from Hermetia illucens Breeding Waste: A Greener Approach for Industrial Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 285, 138302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K.; Conway, C.; Faherty, S.; Quigley, C. A Comparative Analysis of Conventional and Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES)-Mediated Strategies for the Extraction of Chitin from Marine Crustacean Shells. Molecules 2021, 26, 7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainol Abidin, N.A.; Kormin, F.; Zainol Abidin, N.A.; Mohamed Anuar, N.A.F.; Abu Bakar, M.F. The Potential of Insects as Alternative Sources of Chitin: An Overview on the Chemical Method of Extraction from Various Sources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzani, C.; Righi, L.; Vescovi, F.; Maistrello, L.; Caligiani, A. Black Soldier Fly as a New Chitin Source: Extraction, Purification and Molecular/Structural Characterization. LWT 2024, 191, 115618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.; Ruan, L.; Ye, K.; Huang, Z.; Yu, C. Extraction of Chitin from Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) and Its Puparium by Using Biological Treatment. Life 2023, 13, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigode, C.; Hobbi, P.; Jafari, H.; Verwilghen, F.; Baeten, E.; Shavandi, A. Isolation and Physicochemical Properties of Chitin Polymer from Insect Farm Side Stream as a New Source of Renewable Biopolymer. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, E.B.; Lokman, I.H.; Hezmee, M.N.M.; Goh, Y.M.; Zuki, A.B.Z.; Jimoh, A.A. Extraction and Physicochemical Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan Isolated from House Cricket. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 13, 025009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, G.; Mizuta, T.; Akamatsu, M.; Ifuku, S. High-Yield Chitin Extraction and Nanochitin Production from Cricket Legs. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, L.-N. A Review of Chitin Solvents and Their Dissolution Mechanisms. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 38, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmane, E.M.; Taourirte, M.; Eladlani, N.; Rhazi, M. Extraction and Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan from Parapenaeus longirostris from Moroccan Local Sources. Int. J. Polym. Anal. Charact. 2014, 19, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Hong, S.; Lian, H.; Mei, C.; Lee, J.; Wu, Q.; Hubbe, M.A.; Li, M.-C. Recent Advances in Extraction and Processing of Chitin Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 136953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, A.; Olatunde, O.O.; Nimalaratne, C.; House, J.D.; Aluko, R.E.; Bandara, N. Improved Protein Extraction Technology Using Deep Eutectic Solvent System for Producing High Purity Fava Bean Protein Isolates at Mild Conditions. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Zeng, X.; Tang, X.; Sun, Y.; Lei, T.; Lin, L. Extraction of Cellulose Nanocrystals Using a Recyclable Deep Eutectic Solvent. Cellulose 2020, 27, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Su, S.; Xiao, L.-P.; Wang, B.; Sun, R.-C.; Song, G. Catechyl Lignin Extracted from Castor Seed Coats Using Deep Eutectic Solvents: Characterization and Depolymerization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7031–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Hsueh, P.-H.; Ulfadillah, S.A.; Wang, S.-T.; Tsai, M.-L. Exploring the Sustainable Utilization of Deep Eutectic Solvents for Chitin Isolation from Diverse Sources. Polymers 2024, 16, 3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Li, J.; Yan, T.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Kuang, Z.; Ye, M.; Pan, M. Selectivity of Deproteinization and Demineralization Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Production of Insect Chitin (Hermetia illucens). Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 225, 115255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huet, G.; Hadad, C.; González-Domínguez, J.M.; Courty, M.; Jamali, A.; Cailleu, D.; van Nhien, A.N. IL versus DES: Impact on Chitin Pretreatment to Afford High Quality and Highly Functionalizable Chitosan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 269, 118332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarianos, M.; Ojha, S.; Schneider, R.; Schlüter, O.K. Chitin Isolation and Chitosan Production from House Crickets (Acheta domesticus) by Environmentally Friendly Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.A.; Radojčić Redovniković, I.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Matias, A.A.; Paiva, A. Low-Phytotoxic Deep Eutectic Systems as Alternative Extraction Media for the Recovery of Chitin from Brown Crab Shells. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 28729–28741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, W.-R.; Zhang, Y.-C. Facile Production of Chitin from Shrimp Shells Using a Deep Eutectic Solvent and Acetic Acid. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 22631–22638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, D. CO2 Capture by 1,2,3-Triazole-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents: The Unexpected Role of Hydrogen Bonds. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 7376–7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, M.; Dong, X.; Yang, D. The Reaction between K2CO3 and Ethylene Glycol in Deep Eutectic Solvents. Molecules 2024, 29, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banjare, M.K.; Behera, K.; Rub, M.A.; Ghosh, K.K. Micellization Behavior of an Imidazolium Surface-Active Ionic Liquid within Aqueous Solutions of Deep Eutectic Solvents: A Comparative Spectroscopic Study. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 15879–15892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triunfo, M.; Tafi, E.; Guarnieri, A.; Salvia, R.; Scieuzo, C.; Hahn, T.; Zibek, S.; Gagliardini, A.; Panariello, L.; Coltelli, M.B.; et al. Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan Derived from Hermetia illucens, a Further Step in a Circular Economy Process. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, F.N.; Jayeoye, T.J.; Eze, R.C.; Ovatlarnporn, C. Construction of Carboxymethyl Chitosan/PVA/Chitin Nanowhiskers Multicomponent Film Activated with Cotylelobium Lanceolatum Phenolics and in Situ SeNP for Enhanced Packaging Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 128073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishida, K.; Mizuta, T.; Izawa, H.; Ifuku, S. Preparation of Nanochitin from Crickets and Comparison with That from Crab Shells. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, O.; Zor, T. Linearization of the Bradford Protein Assay. J. Vis. Exp. 2010, 38, e1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, F.N.; Muangrat, R.; Singh, S.; Jirarattanarangsri, W.; Siriwoharn, T.; Chalermchat, Y. Upcycling of Defatted Sesame Seed Meal via Protein Amyloid-Based Nanostructures: Preparation, Characterization, and Functional and Antioxidant Attributes. Foods 2024, 13, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J. Gradient Heating Activated Ammonium Persulfate Oxidation for Efficient Preparation of High-Quality Chitin Nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 340, 122308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and Chitosan: Properties and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Goswami, P.; Paritosh, K.; Kumar, M.; Pareek, N.; Vivekanand, V. Seafood Waste: A Source for Preparation of Commercially Employable Chitin/Chitosan Materials. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2019, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, J.; Suenaga, S.; Osada, M. Effect of the Degree of Acetylation on the Physicochemical Properties of α-Chitin Nanofibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J. Effects of Degree of Deacetylation on Hemostatic Performance of Partially Deacetylated Chitin Sponges. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdini, B.; Biancarosa, I.; Cardinaletti, G.; Illuminati, S.; Annibaldi, A.; Girolametti, F.; Fanelli, M.; Tulli, F.; Pinto, T.; Truzzi, C. Modulating the Nutritional Value of Acheta domesticus (House Cricket) through the Eco-Sustainable Ascophyllum nodosum Dietary Supplementation. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 140, 107263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.K.P.; Brück, D.W.; Brück, W.M. Isolation of Proteolytic Bacteria from Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) Exoskeletons to Produce Chitinous Material. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364, fnx177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nessa, F.; Masum, S.M.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Roy, S.K.; Hossain, M.M.; Jahan, M.S. A Process for the Preparation of Chitin and Chitosan from Prawn Shell Waste. Bangladesh J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2010, 45, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Tafi, E.; Paul, A.; Salvia, R.; Falabella, P.; Zibek, S. Current State of Chitin Purification and Chitosan Production from Insects. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 2775–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popadić, A.; Tsitlakidou, D. Regional Patterning and Regulation of Melanin Pigmentation in Insects. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2021, 69, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayrova, A.; Lopatin, S.; Varlamov, V. Obtaining Chitin, Chitosan and Their Melanin Complexes from Insects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 167, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, F.N.; Eze, R.C.; Singh, S.; Okpara, K.E. Fabrication of a Versatile and Efficient Ultraviolet Blocking Biodegradable Composite Film Consisting of Tara Gum/PVA/Riceberry Phenolics Reinforced with Biogenic Riceberry Phenolic-Rich Extract-Nano-silver. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, M.-T.; Yang, J.-H.; Mau, J.-L. Physicochemical Characterization of Chitin and Chitosan from Crab Shells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 75, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Sofi, K.; Sargin, I.; Mujtaba, M. Changes in Physicochemical Properties of Chitin at Developmental Stages (Larvae, Pupa and Adult) of Vespa crabro (wasp). Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 145, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Hamdan, Y.; Oudadesse, H.; Elouali, S.; Eladlani, N.; Lefeuvre, B.; Rhazi, M. Exploring the Potential of Chitosan from Royal Shrimp Waste for Elaboration of Chitosan/Bioglass Biocomposite: Characterization and “in Vitro” Bioactivity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, G.; Cabrera, G.; Taboada, E.; Miranda, S.P. Chitin Characterization by SEM, FTIR, XRD, and 13C Cross Polarization/Mass Angle Spinning NMR. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 93, 1876–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Huang, W.-C.; Guo, N.; Zhang, S.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. Two-Step Separation of Chitin from Shrimp Shells Using Citric Acid and Deep Eutectic Solvents with the Assistance of Microwave. Polymers 2019, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Baran, T.; Erdoğan, S.; Menteş, A.; Özüsağlam, M.A.; Çakmak, Y.S. Physicochemical Comparison of Chitin and Chitosan Obtained from Larvae and Adult Colorado Potato Beetle (Leptinotarsa decemlineata). Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2014, 45, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witono, J.R.B.; Tan, D.; Deandra, P.P.; Miryanti, Y.I.P.A.; Wanta, K.C.; Santoso, H.; Bulin, C.D.Q.M.; Astuti, D.A. Strategic Advances in Efficient Chitin Extraction from Black Soldier Fly Puparia: Uncovering the Potential for Direct Chitosan Production. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.-K.; Kong, B.-G.; Jeong, Y.-I.; Lee, C.H.; Nah, J.-W. Physicochemical Characterization of α-Chitin, β-Chitin, and γ-Chitin Separated from Natural Resources. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 3423–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Erdogan, S.; Mol, A.; Baran, T. Comparison of Chitin Structures Isolated from Seven Orthoptera Species. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebora, M.; Salerno, G.; Piersanti, S.; Saitta, V.; Morelli Venturi, D.; Li, C.; Gorb, S. The Armoured Cuticle of the Black Soldier Fly Hermetia illucens. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, P.; Lian, H. Versatile Acid Base Sustainable Solvent for Fast Extraction of Various Molecular Weight Chitin from Lobster Shell. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 201, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowski, B.; Marzec, A. Chitosan vs. Chitin: Comparative Study of Functional pH Bioindicators Synthesized from Natural Red Dyes and Biopolymers as Potential Packaging Additives. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 150, 109670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozel, N.; Elibol, M. Chitin and Chitosan from Mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) Using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Nie, L.; Pei, X.; Zhang, L.; Long, S.; Li, Y.; Jiao, H.; Gong, W. Seafood Waste Derived Pt/Chitin Nanocatalyst for Efficient Hydrogenation of Nitroaromatic Compounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Ratner, B.D. Differentiating Calcium Carbonate Polymorphs by Surface Analysis Techniques—An XPS and TOF-SIMS Study. Surf. Interface Anal. 2008, 40, 1356–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Lu, X.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, J.; Xin, J.; Shi, C.; Wang, K.; Zhang, S. One-Step Preparation of an Antibacterial Chitin/Zn Composite from Shrimp Shells Using Urea-Zn(OAc)2·2H2O Aqueous Solution. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 2212–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-C.; Zhao, D.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. An Efficient Method for Chitin Production from Crab Shells by a Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2022, 4, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazali, A.L.; AlMasoud, N.; Amran, S.K.; Alomar, T.S.; Pa’ee, K.F.; El-Bahy, Z.M.; Yong, T.-L.K.; Dailin, D.J.; Chuah, L.F. Physicochemical and Thermal Characteristics of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Fang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wu, M.; Zhang, W.; Ou, X.; Li, H.; Shang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y. Green Preparation of β-Chitins from Squid Pens by Using Alkaline Deep Eutectic Solvents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DES | Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | Hydrogen Bond Donor | Molar Ratio | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium carbonate: glycerol (KG DES) | Potassium carbonate | Glycerol | 1:7 | 11 |

| Choline chloride: glycerol (CCG DES) | Choline chloride | Glycerol | 1:2 | 5.5 |

| Chitin Abbreviation | Description of Chitin Sample | Concise Method of Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| CS chitin | Crab shell chitin flakes obtained commercially from Sigma-Aldrich. | Commercially obtained crab shell chitin flakes. |

| CE chitin | Cricket chitin obtained using conventional extraction (without decolorization). | Cricket meal → Demineralization (1 M HCl) → Deproteinization (2 M NaOH) → CE chitin. |

| KG chitin | Cricket chitin obtained using potassium carbonate/glycerol deep eutectic solvent (without decolorization). | Cricket meal → one-pot extraction with freshly prepared KG DES → KG chitin. |

| CCG chitin | Cricket chitin obtained using choline chloride: glycerol deep eutectic solvent (without decolorization). | Cricket meal → one-pot extraction with freshly prepared CCG DES → CCG chitin. |

| RKG chitin | Cricket chitin obtained using recovered potassium carbonate/glycerol deep eutectic solvent (without decolorization). | Cricket meal → one-pot extraction with recovered KG DES (i.e., RKG DES) → RKG chitin. |

| RCCG chitin | Cricket chitin obtained using recovered choline chloride/glycerol deep eutectic solvent (without decolorization). | Cricket meal → one-pot extraction with recovered CCG DES (i.e., RCCG DES) → RCCG chitin. |

| DCE chitin | Decolorized cricket chitin obtained using conventional extraction and decolorization. | Cricket meal → Demineralization (1 M HCl) → Deproteinization (2 M NaOH) → CE chitin → Decolorization (aqueous NaOCl: 1% v/v) → DCE chitin |

| DKG chitin | Decolorized cricket chitin obtained using potassium carbonate/glycerol deep eutectic solvent and decolorization. | Cricket meal → one-pot extraction with freshly prepared KG DES → KG chitin → Decolorization (5% v/v H2O2) → DKG chitin |

| DCCG chitin | Decolorized cricket chitin obtained using choline chloride/glycerol deep eutectic solvent with decolorization. | Cricket meal → one-pot extraction with freshly prepared CCG DES → CCG chitin → Decolorization (5% v/v H2O2) → DCCG chitin. |

| Sample | Yield (%) | DA (%) | Moisture (%) | Ash (%) | Protein (%) | Purity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS chitin | *** | 79.42 ± 1.02 b | 4.56 ± 0.03 g | 1.87 ± 0.05 e | 2.64 ± 0.03 a | 89.93 ± 0.04 f |

| CE chitin | 8.74 ± 0.13 b | 77.22 ± 2.89 a | 4.04 ± 0.01 c | 0.41 ± 0.02 b | 3.29 ± 0.01 c | 92.26 ± 0.01 h |

| KG chitin | 9.94 ± 0.21 c | 77.97 ± 1.41 a | 3.75 ± 0.02 a | 1.41 ± 0.07 d | 5.54 ± 0.04 e | 89.3 ± 0.14 e |

| CCG chitin | 18.17 ± 0.50 d | 81.28 ± 2.13 b | 4.14 ± 0.01 d | 0.73 ± 0.07 c | 22.18 ± 0.52 h | 72.95 ± 0.20 b |

| RKG chitin | 10.33 ± 0.32 c | 78.27 ± 1.07 ab | 4.27 ± 0.05 e | 1.39 ± 0.01 d | 5.72 ± 0.06 f | 88.62 ± 0.03 d |

| RCCG chitin | 22.94 ± 0.42 e | 84.27 ± 1.21 c | 5.82 ± 0.03 h | 0.80 ± 0.02 c | 22.49 ± 0.83 h | 70.89 ± 0.30 a |

| DCE chitin | 6.54 ± 0.16 a | 77.08 ± 0.98 a | 3.89 ± 0.01 b | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 2.86 ± 0.03 b | 93.16 ± 0.02 i |

| DKG chitin | 8.65 ± 0.21 b | 77.71 ± 1.61 a | 4.45 ± 0.02 f | 0.62 ± 0.03 c | 4.37 ± 0.05 d | 90.56 ± 0.03 g |

| DCCG chitin | 17.00 ± 0.53 d | 81.48 ± 0.77 b | 5.78 ± 0.03 h | 0.39 ± 0.07 b | 20.62 ± 1.38 g | 73.21 ± 0.50 c |

| Samples | Color Parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | WI | ΔE | |

| CS chitin | 74.31 ± 0.33 f | 2.66 ± 0.04 b | 23.93 ± 0.9 g | 64.78 ± 0.38 g | |

| CE chitin | 51.32 ± 0.22 d | 3.34 ± 0.08 cd | 1.83 ± 0.09 a | 51.17 ± 0.22 d | 31.9 ± 0.72 d |

| KG chitin | 50.45 ± 0.14 c | 2.85 ± 0.02 bc | 1.54 ± 0.07 a | 50.34 ± 0.14 c | 32.72 ± 0.97 d |

| CCG chitin | 51.68 ± 0.14 d | 4.39 ± 0.23 e | 4.63 ± 0.42 d | 51.26 ± 0.20 d | 29.79 ± 0.67 c |

| RKG chitin | 46.07 ± 0.91 b | 3.08 ± 0.10 c | 3.58 ± 0.32 b | 45.87 ± 0.88 b | 34.81 ± 0.85 e |

| RCCG chitin | 43.41 ± 0.25 a | 3.69 ± 0.37 d | 4.03 ± 0.58 c | 43.14 ± 0.20 a | 36.77 ± 0.48 f |

| DCE chitin | 83.81 ± 0.05 f | 1.16 ± 0.09 a | 13.60 ± 0.12 e | 78.83 ± 0.03 h | 14.13 ± 0.45 b |

| DKG chitin | 65.41 ± 0.51 e | 4.59 ± 0.38 e | 14.25 ± 0.23 e | 62.31 ± 0.60 f | 13.30 ± 1.00 b |

| DCCG chitin | 64.78 ± 0.50 e | 6.09 ± 0.19 f | 19.60 ± 0.29 f | 59.24 ± 0.39 e | 11.03 ± 0.15 a |

| C 1s | N 1s | O 1s | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Energy (eV) | 285.0 | 286.5 | 288.1 | 289.5 | 400.0 | 401.1 | 531.4 | 532.5 | 533.2 | 534.5 |

| Bonds/functional group | C-C; C=C | C-OH; C-O; C-N; C-Cl | C=O; N-C=O; C-O-C | -COOH; O-C=O | C-NH2; N-C=O | -NH3+ | O=C; O-Si | C-O-C | O-C | -OH; H2Oads |

| CS chitin | 21.4% | 48.8% | 25.6% | 4.2% | 83.9% | 16.1% | 18.5% | 24.3% | 52.8% | 4.4% |

| DCE chitin | 50.3% | 34.1% | 15.6% | - | 100% | - | 23.4% | 24.7% | 48.6% | 3.3% |

| DKG chitin | 55.1% | 31.4% | 13.5% | - | 100% | - | 19.6% | 32.1% | 44% | 4.4% |

| DCCG chitin | 65.1% | 16.5 + 8.5% | 7.1% | 2.7% | 100% | - | 28.6% | 24.9% | 21.1% | 3.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eze, F.N.; Muangrat, R.; Jirarattanarangsri, W.; Siriwoharn, T.; Chalermchat, Y. Sustainable Production of Chitin from Supercritical CO2 Defatted Domestic Cricket (Acheta domesticus L.) Meal: One-Pot Preparation, Characterization, and Effects of Different Deep Eutectic Solvents. Polysaccharides 2025, 6, 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040115

Eze FN, Muangrat R, Jirarattanarangsri W, Siriwoharn T, Chalermchat Y. Sustainable Production of Chitin from Supercritical CO2 Defatted Domestic Cricket (Acheta domesticus L.) Meal: One-Pot Preparation, Characterization, and Effects of Different Deep Eutectic Solvents. Polysaccharides. 2025; 6(4):115. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040115

Chicago/Turabian StyleEze, Fredrick Nwude, Rattana Muangrat, Wachira Jirarattanarangsri, Thanyaporn Siriwoharn, and Yongyut Chalermchat. 2025. "Sustainable Production of Chitin from Supercritical CO2 Defatted Domestic Cricket (Acheta domesticus L.) Meal: One-Pot Preparation, Characterization, and Effects of Different Deep Eutectic Solvents" Polysaccharides 6, no. 4: 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040115

APA StyleEze, F. N., Muangrat, R., Jirarattanarangsri, W., Siriwoharn, T., & Chalermchat, Y. (2025). Sustainable Production of Chitin from Supercritical CO2 Defatted Domestic Cricket (Acheta domesticus L.) Meal: One-Pot Preparation, Characterization, and Effects of Different Deep Eutectic Solvents. Polysaccharides, 6(4), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/polysaccharides6040115