Is Crime Associated with Obesity and High Blood Pressure? Repeated Cross-Sectional Evidence from a Peruvian Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Conceptual Connection Between Crime, Obesity, and High Blood Pressure

2.2. Relation Between Crime and Obesity

2.3. Connection Between Crime and High Blood Pressure

2.4. Connection Between Crime, Obesity, and High Blood Pressure

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Population

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Crime Incidence

3.3.2. High Blood Pressure and Obesity

3.3.3. Covariates

3.4. Statistical Analysis

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Cross-Sectional Descriptive Statistics

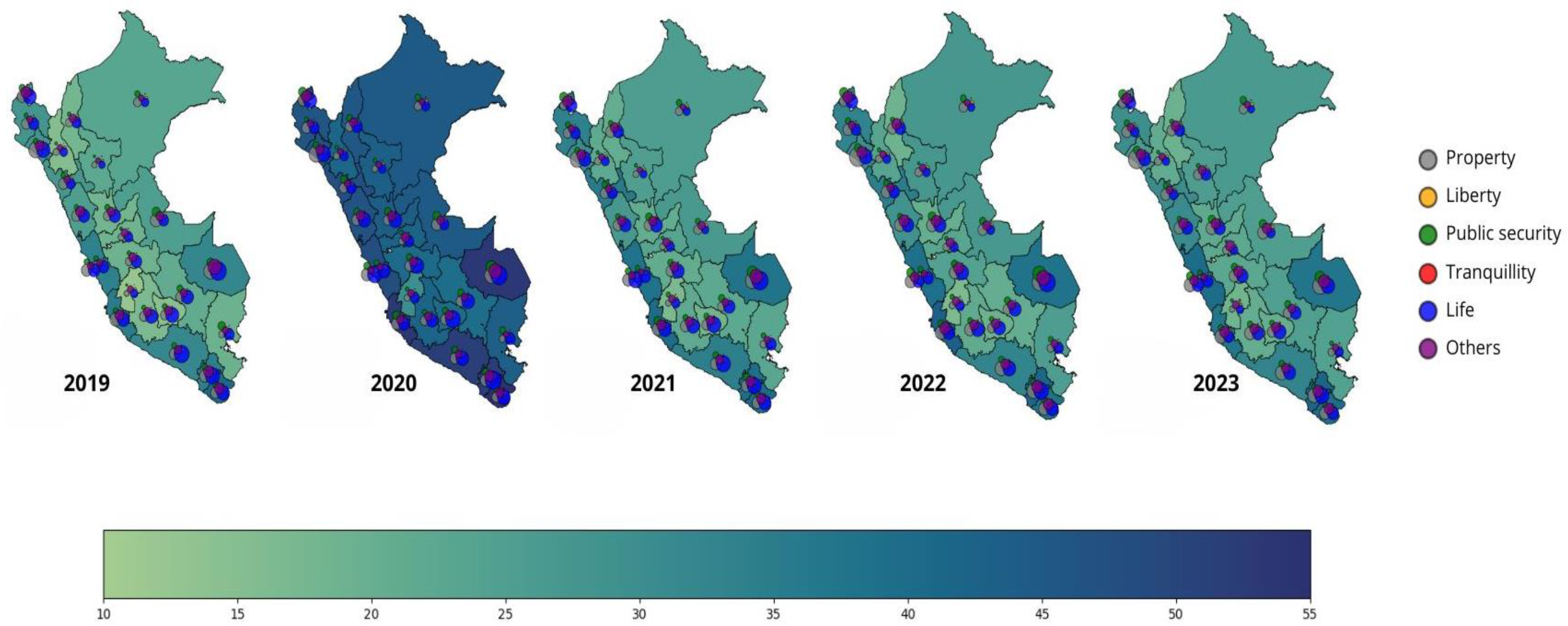

4.2. Region-Level High Blood Pressure, Obesity Prevalence, and Crime Rates (2019–2023)

4.3. Correlation Analyses

4.4. Regression Coefficients

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Public Policy

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| WC | Waist Circumference |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal |

| ENDES | Demographic and Family Health Survey |

| INEI | National Institute of Statistics and Informatics |

| RCS | Repeated Cross-Sections |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Study on Homicide 2023; United Nations: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC). Global Organized Crime Index 2023; GI-TOC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bisca, P.M.; Chau, V.; Dudine, P.; Espinoza, R.A.; Fournier, J.-M.; Guérin, P.; Hansen, N.-J.; Salas, J. Violent Crime and Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernet Kempers, E. Between informality and organized crime: Criminalization of small-scale mining in the Peruvian rainforest. In Illegal Mining; Zabyelina, Y., van Uhm, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inquilla, J.; López, M.; Catacora, E.; Flores, E. La morfología de la criminalidad urbana en el Perú: Un análisis de tendencias, niveles y factores de riesgo. Andamios 2024, 21, 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- FAO; IFAD; PAHO; UNICEF; WFP. Latin America and the Caribbean–Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition 2023: Statistics and Trends; FAO: Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bazoukis, G.; Loscalzo, J.; Hall, J.L.; Bollepalli, S.C.; Singh, J.P.; Armoundas, A.A. Impact of social determinants of health on cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e039031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.E.; Elorriaga, N.; Gibbons, L.; Melendi, S.; Chaparro, M.; Calandrelli, M.; Lanas, F.; Mores, N.; Ponzo, J.; Poggio, R.; et al. Attributes of the food and physical activity built environments from the Southern Cone of Latin America. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metkus, T.S. New dimensions assessing poverty and cardiovascular disease. JACC Adv. 2024, 3, 100931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebar, W.R.; Gil, F.C.S.; Delfino, L.D.; Souza, J.M.; Mota, J.; Christofaro, D.G.D. Relationship of obesity with lifestyle and comorbidities in public school teachers—A cross-sectional study. Obesities 2022, 2, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena Chávez, J.E. Prevalencia de sobrepeso y obesidad en el Perú. Rev. Peru. Ginecol. Obstet. 2017, 63, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Ocon, V.; Cueva-Peredo, F.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A. Prevalence, trends, and factors associated with hypertensive crisis among Peruvian adults. Cad. Saude Publica 2024, 40, e00155123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal-Zegarra, D.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Bernabe-Ortiz, A. Short-term trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of arterial hypertension in Peru. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021, 35, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavero, V.; Hernández-Vásquez, A.; Miranda, J.J.; Alata, P.; Alegre, M.; Diez-Canseco, F. Satisfacción y percepciones sobre aspectos de la ciudad que afectan la salud en Lima Metropolitana, 2010–2019. Rev. Peru. Med. Exp. Salud Publica 2022, 39, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, A.; Asante, S.A. Neighbourhood crime and obesity: Longitudinal evidence from Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 337, 116289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolzenberg, L.; D’Alessio, S.J.; Flexon, J.L. The impact of violent crime on obesity. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.M.; Blanco, E.; Delva, J.; Burrows, R.; Reyes, M.; Lozoff, B.; Gahagan, S. Perception of neighborhood crime and drugs increases cardiometabolic risk in Chilean adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topel, M.L.; Kelli, H.M.; Lewis, T.T.; Dunbar, S.B.; Vaccarino, V.; Taylor, H.A.; Quyyumi, A.A. High neighborhood incarceration rate and cardiometabolic disease in nonincarcerated Black individuals. Ann. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, A.J.; Matthews, K.A. Childhood poly-victimization and body mass index in college women. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurito, A.; Schwartz, A.E.; Elbel, B. Exposure to local violent crime and childhood obesity and fitness. Health Place 2022, 78, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, C.R.; Winata, F.; Adams, A.M.; McLafferty, S.L.; Sheehan, K.M.; Zenk, S.N. County-level associations between food retailer availability and violent crime rate. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 14415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letarte, L.; Samadoulougou, S.; McKay, R.; Quesnel-Vallée, A.; Waygood, E.O.D.; Lebel, A. Neighborhood deprivation and obesity: Sex-specific effects. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 306, 115049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yip, C.; Sarma, S.; Wilk, P. Association between social cohesion and physical activity in Canada: A multilevel analysis. SSM–Popul. Health 2016, 2, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangerfield, F.; Ball, K.; Dickson-Swift, V.; Thornton, L.E. Understanding regional food environments. Health Place 2021, 71, 102652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivara, F.; Adhia, A.; Lyons, V.; Massey, A.; Mills, B.; Morgan, E.; Simckes, M.; Rowhani-Rahbar, A. The effects of violence on health. Health Aff. 2019, 38, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, E.L.; Wroblewski, K.E.; Boyd, K.; Makelarski, J.A.; Peek, M.E.; Lindau, S.T. Police-recorded crime and disparities in obesity and blood pressure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, M.D.; Mair, C.F.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Brooks, M.M.; Méndez, D.D.; Naimi, A.I.; Reeves, A.; Hedderson, M.; Janssen, I.; Fabio, A. Neighborhood socioeconomic vulnerability and midlife blood pressure. Health Place 2023, 82, 103033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, G.M.; Posick, C. Risk factors for direct vs. indirect exposure to violence. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dustmann, C.; Fasani, F. The effect of local area crime on mental health. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2013, 85, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Perú–Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud 2019; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2020. Available online: https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Perú–Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud 2020; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2021. Available online: https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Perú–Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud 2021; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2022. Available online: https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Perú–Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud 2022; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2023. Available online: https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática (INEI). Perú–Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud 2023; INEI: Lima, Peru, 2024. Available online: https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Peruvian National Open Data Platform. Cantidad de Delitos Denunciados en el Ministerio Público a Nivel Nacional 2019–2023. Available online: https://www.datosabiertos.gob.pe (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Ferrer, M.; del Prado González, N. Medidas de frecuencia y de asociación en epidemiología clínica. An. Pediatr. Contin. 2013, 11, 346–349. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD (PHQ). JAMA 1999, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, H.E.; Johnston, R. Repeated cross-sections in survey data. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igual, L.; Seguí, S. Introduction to Data Science: A Python Approach to Concepts, Techniques and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aleixandre-Benavent, R.; Sapena, A.F.; Peset, F. Compartir recursos útiles para la investigación: Datos abiertos. Educ. Med. 2019, 22, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnau, J.; Bono, R. Estudios longitudinales: Modelos de diseño y análisis. Escr. Psicol. 2008, 2, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Khatib, M.N.; Balaraman, A.K.; Kaur, M.; Srivastava, M.; Barwal, A.; Prasad, G.V.S.; Rajput, P.; Syed, R.; Sharma, G.; et al. Association of exposure to violence and risk of hypertension. Public Health 2025, 243, 105722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamm, A.; Karayeva, E.; Oliveira, M.L.; Kahouadji, N.; Grippo, P.; Wolf, P.G.; Mutlu, E.; Tussing-Humphreys, L.; Kim, S.J. Neighborhood homicide rate and colorectal adenoma. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2024, 8, pkae110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, S.M.; Heinze, J.E.; Miller, A.L.; Stoddard, S.A.; Zimmerman, M.A. Exposure to violence and cortisol response. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión-Mena, F.; Gottsbacher, M. Border violence in Latin America: An expression of complementary asymmetries. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Latin America; Bada, X., Rivera-Sánchez, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, V.D.; Xavier-Gomes, L.M.; Barbosa, T.L.D.A. Mortalidade por homicídios em linha de fronteira no Paraná, Brasil. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 3107–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widner, B.; Reyes-Loya, M.L.; Enomoto, C.E. Crimes and violence in Mexico: Evidence from panel data. Soc. Sci. J. 2011, 48, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, L.U.T.; Anderson, C.; Thomas, S.; Vernia, H.; Howe, J.K.; Tyroch, A.H.; Fitzgerald, T.N. Penetrating trauma in children on the United States-Mexico border: Hispanic ethnicity is not a risk factor. Injury 2018, 49, 1358–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.H.; Fone, D.L.; Chiaradia, A.J. Impact of spatial network layout on social cohesion. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman-Smith, D.; Garthe, R.C.; Schoeny, M.E.; Cosey-Gay, F.N.; Harris, C.; Brown, C.H.; Villamar, J.A. Impact of the Communities That Care approach. Prev. Sci. 2024, 25, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylona, E.K.; Shehadeh, F.; Fleury, E.; Kalligeros, M.; Mylonakis, E. Accessibility to fast food/open green spaces and obesity. Am. J. Med. 2020, 133, 340–346.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Lin, H.; Tan, H.; Liu, X. Aging and mortality risk among hypertensive individuals. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, X.; Kong, Y. Biological aging and cardiovascular health. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 132, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed | High blood pressure | Obesity | High blood pressure | Obesity | High blood pressure | Obesity | High blood pressure | Obesity | High blood pressure | Obesity |

| Sex | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.31 |

| Age | 57.80 | 42.27 | 58.03 | 42.75 | 55.72 | 40.69 | 55.97 | 41.35 | 57.52 | 41.58 |

| High blood pressure category | 2.65 | 2.10 | 2.67 | 2.17 | 2.65 | 2.20 | 2.62 | 2.25 | 2.56 | 2.11 |

| Mental Health | 2.24 | 1.85 | 2.26 | 1.91 | 2.25 | 1.85 | 2.32 | 1.95 | 2.33 | 1.93 |

| BMI category | 3.32 | 4.29 | 3.39 | 4.32 | 3.38 | 4.32 | 3.36 | 4.32 | 3.31 | 4.32 |

| Residential area | 1.65 | 1.77 | 1.69 | 1.76 | 1.68 | 1.76 | 1.65 | 1.75 | 1.62 | 1.75 |

| Location of residence | 2.81 | 2.63 | 2.71 | 2.63 | 2.76 | 2.64 | 2.81 | 2.65 | 2.90 | 2.67 |

| Years | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | High BLOOD Pressure Prevalence | Obesity Prevalence | |||||||||

| r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | r | ||

| Covariates | Geographic location | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.11 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.39 | 0.37 | 0.32 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | |

| Sex | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Mental health | −0.03 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.06 | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | |

| BMI | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.19 | |

| Typology crime rate | Liberty | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.16 | −0.04 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.20 |

| Other | 0.02 | −0.40 | −0.34 | −0.28 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.08 | |

| Property | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.38 | |

| Public security | −0.24 | −0.38 | −0.23 | −0.26 | −0.25 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.22 | |

| Tranquility | 0.34 | 0.07 | 0.18 | −0.12 | −0.44 | 0.61 | 0.23 | 0.00 | −0.09 | −0.30 | |

| Life, body, and health offenses | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.19 | −0.07 | 0.03 | 0.45 | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.35 | |

| Variables | High Blood Pressure Prevalence | Obesity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | |||

| Coefficient p > |β| | Coefficient p > |β| | ||

| Individual characteristics | Sex (female) | −0.001 | 0.083 * |

| Age | −0.004 *** | 0.003 ** | |

| BMI | 0.010 *** | 0.008 * | |

| Mental health | No depression | −0.0003 | 0.0153 |

| Minimal depression | 0.0622 | −0.105 * | |

| Moderate depression | 0.0814 | −0.0305 | |

| Moderately severe depression | 0.1742 | −0.016 | |

| Severe depression | −0.0783 | 0.1786 | |

| Geographic location | Ancash | 1.277 *** | 13.267 *** |

| Apurimac | −6.988 *** | 6.185 *** | |

| Arequipa | −0.0702 | 26.8246 *** | |

| Ayacucho | −0.325 *** | 7.756 *** | |

| Cajamarca | 6.177 *** | −8.861 *** | |

| Callao | 3.762 *** | 27.660 *** | |

| Cusco | −4.711 *** | 5.025 *** | |

| Huancavelica | −4.001 *** | −14.893 *** | |

| Huánuco | −3.643 *** | 7.750 *** | |

| Ica | 3.257 *** | 27.291 *** | |

| Junín | −3.818 *** | 6.728 *** | |

| La Libertad | 0.965 *** | 10.737 *** | |

| Lambayeque | 4.678 *** | 31.913 *** | |

| Lima | 6.087 *** | 19.045 *** | |

| Loreto | 2.633 *** | −2.323 *** | |

| Madre de Dios | −15.084 *** | 46.497 *** | |

| Moquegua | −3.429 *** | 36.004 *** | |

| Pasco | 2.174 *** | −6.811 *** | |

| Piura | 4.401 *** | 10.319 *** | |

| Puno | 0.460 *** | −2.202 *** | |

| San Martin | 0.539 *** | −3.837 *** | |

| Tacna | 4.166 *** | 27.380 *** | |

| Tumbes | −0.996 *** | 16.756 *** | |

| Ucayali | −5.289 *** | 5.253 *** | |

| Residential area (urban) | 0.0068 | −0.0142 | |

| Typology crime rate | Property | −0.004 *** | −0.011 *** |

| Public security | 0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | |

| Tranquility | 0.005 * | −0.051 *** | |

| Life, body and health offenses | 0.008 *** | −0.012 *** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramos-Sandoval, R.; Palacios, J.B.; Ramos, M.L.; Baca Marroquín, E.; Peche, A.F.V.; Arias, N.I.A. Is Crime Associated with Obesity and High Blood Pressure? Repeated Cross-Sectional Evidence from a Peruvian Study. Obesities 2025, 5, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040095

Ramos-Sandoval R, Palacios JB, Ramos ML, Baca Marroquín E, Peche AFV, Arias NIA. Is Crime Associated with Obesity and High Blood Pressure? Repeated Cross-Sectional Evidence from a Peruvian Study. Obesities. 2025; 5(4):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040095

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamos-Sandoval, Rosmery, Janina Bazalar Palacios, Milagros Leonardo Ramos, Emily Baca Marroquín, Arelly Fernanda Vega Peche, and Nicolas Ismael Alayo Arias. 2025. "Is Crime Associated with Obesity and High Blood Pressure? Repeated Cross-Sectional Evidence from a Peruvian Study" Obesities 5, no. 4: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040095

APA StyleRamos-Sandoval, R., Palacios, J. B., Ramos, M. L., Baca Marroquín, E., Peche, A. F. V., & Arias, N. I. A. (2025). Is Crime Associated with Obesity and High Blood Pressure? Repeated Cross-Sectional Evidence from a Peruvian Study. Obesities, 5(4), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040095