Anthropometric Indicators of Obesity as Screening Tools for Hypertriglyceridemia in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

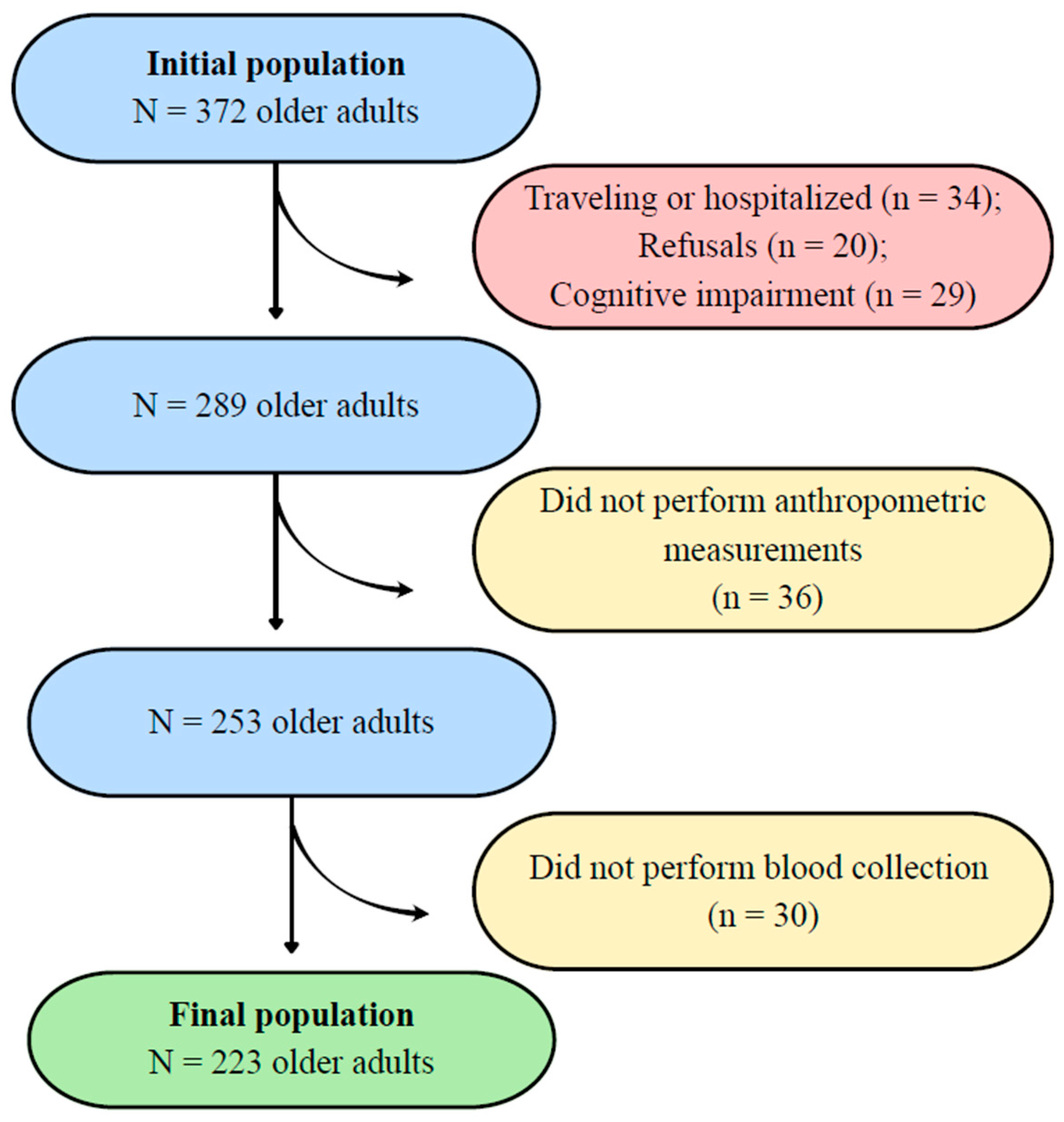

2.1. Study Design, Location, and Population

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Independent Variables (Discriminators)

2.6. Dependent Variable (Outcome)

2.7. Adjustment Variables (Covariates)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Faludi, A.; Izar, M.; Saraiva, J.; Chacra, A.; Bianco, H.; Neto, A.A.; Bertolami, A.; Pereira, A.; Lottenberg, A.; Sposito, A.; et al. Atualização da diretriz brasileira de dislipidemias e prevenção da aterosclerose–2017. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2017, 109, 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.P.; Marchena, M.B.; Rebatta, F.B.; Valladares, E.R.; Zamora, R.A. Frecuencia y factores asociados a las enfermedades crónicas no transmisibles en adultos mayores en el Perú, 2005. An. Fac. Med. 2022, 83, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Koba, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Yokota, Y.; Tsunoda, F.; Shoji, M.; Itoh, Y.; Hamazaki, Y.; Kobayashi, Y. Small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is a promising biomarker for secondary prevention in older men with stable coronary artery disease. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2018, 18, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, F.O.; Júnior, C.Q.d.L.; Siqueira, I.C.; de Oliveira, N.C.; Tavares, R.S.; Rocha, T.M.D.; de Moura, A.L.D. Avaliação do perfil lipídico de pacientes acima de 60 anos de idade atendidos em um laboratório-escola. Rev. Bras. Anal. Clin. 2017, 49, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.B.; Agostini, J.A.; Bianchi, P.D.; Garces, S.B.B.; Hansen, D.; Moreira, P.R.; Schwanke, C.H.A. Síndrome metabólica e estado nutricional de idosos cadastrados no HiperDia. Sci. Med. 2016, 26, ID23100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.; Pedreira, R.B.S.; Silva, R.R.; Barbosa, R.d.S.; Neto, P.d.F.V.; Casotti, C.A. Anthropometric indicators of adiposity as predictors of systemic arterial hypertension in older people: A cross-sectional analysis. Rev. Nutr. 2023, 36, e220137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, Y.S.; dos Santos, L.; da Silva, D.J.; Santos, E.S.; Caires, S.d.S.; Neto, P.d.F.V.; de Almeida, C.B.; Santana, P.d.S.; Barbosa, R.d.S.; Casotti, C.A. Anthropometric indicators of obesity as screening tools for low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in older adults: A cross-sectional study. Lipids 2025, 60, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, C.M.; Fernandes, M.H.; Carneiro, J.A.O.; da Silva Coqueiro, R.; Pereira, R. Increased waist circumference as an independent predictor of hypercholesterolemia in community-dwelling older people. Healthc. Low. Resour. Settings 2018, 6, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Júnior, C.A.; Coqueiro, R.d.S.; Carneiro, J.A.O.; Pereira, R.; Barbosa, A.R.; de Magalhães, A.C.M.; Oliveira, M.V.; Fernandes, M.H. Anthropometric indicators in hypertriglyceridemia discrimination: Application as screening tools in older adults. J. Nurs. Meas. 2016, 24, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuschieri, S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2019, 13, S31–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casotti, C.A.; Almeida, C.B.; Santos, L.; Valença Neto, P.F.; Carmo, T.B. Condições de saúde e estilo de vida de idosos: Métodos e desenvolvimento do estudo. Prat. Cuid. Rev. Saude Col. 2021, 2, e12643. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, D.J.; dos Santos, L.; de Souza, Y.S.; Neto, P.d.F.V.; Santana, P.d.S.; de Almeida, C.B.; Casotti, C.A. Physical fitness according to the level of physical activity in older people: A cross-sectional analysis. Fisioter. Mov. 2023, 36, e36134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icaza, M.G.; Albala, C. Minimental State Examinations (MMSE) del Estudio de Demencia en Chile: Análisis Estadístico. 1999. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/pah-28530 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Bertolucci, P.H.; Brucki, S.M.; Campacci, S.R.; Juliano, Y. O mini-exame do estado mental em uma população geral: Impacto da escolaridade. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 1994, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, Y.S.; dos Santos, L.; da Silva, D.J.; Barbosa, R.d.S.; Pinto, L.L.T.; Neto, P.d.F.V.; Casotti, C.A. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype in older adults: Prevalence and associated factors. Cad. Saude Colet. 2024, 32, e32040610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Committee. Physical Status: The Use of and Interpretation of Anthropometry, Report of a WHO Expert Committee; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37003 (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Bergman, R.N.; Stefanovski, D.; Buchanan, T.A.; Sumner, A.E.; Reynolds, J.C.; Sebring, N.G.; Xiang, A.H.; Watanabe, R.M. A better index of body adiposity. Obesity 2011, 19, 1083–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, S.; Yoshinaga, H. Waist/height ratio as a simple and useful predictor of coronary heart disease risk factors in women. Intern. Med. 1995, 34, 1147–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, R. A simple model-based index of abdominal adiposity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1991, 44, 955–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobas, R.; Rodacki, M.; Giacaglia, L.; Calliari, L.E.; Noronha, R.M.; Valerio, C.; Custódio, J.; Scharf, M.; Barcellos, C.R.G.; Tomarchio, M.P.; et al. Diagnóstico do Diabetes e Rastreamento do Diabetes Tipo 2; Diretriz Oficial da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes; Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes: São Paulo, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, T.R.B.; Antunes, P.C.; Rodriguez-Añez, C.R.; Mazo, G.Z.; Petroski, E.L. Reprodutibilidade e validade do Questionário Internacional de Atividade Física (IPAQ) em homens idosos. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2007, 13, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, T.B.; Mazo, G.Z.; Barros, M.V.G. Aplicação do questionário internacional de atividades físicas para avaliação do nível de atividades física de mulheres idosas: Validade concorrente e reprodutibilidade teste-reteste. Rev. Bras. Cien Mov. 2004, 12, 25–34. Available online: https://portalrevistas.ucb.br/index.php/rbcm/article/view/538/11870 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahm, F.S. Receiver operating characteristic curve: Overview and practical use for clinicians. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2022, 75, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delong, E.R.; Delong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Camblor, P.; Pardo-Fernández, J.C. The Youden index in the generalized receiver operating characteristic curve context. Int. J. Biostat. 2019, 15, 20180060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, L.M.S.; Scazufca, M.; Menezes, P.R. Methods for estimating prevalence ratios in cross-sectional studies. Rev. Saude Publica 2008, 42, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenland, S.; Daniel, R.; Pearce, N. Outcome modelling strategies in epidemiology: Traditional methods and basic alternatives. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 45, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behzadi, M.; Jowshan, M.R.; Shokri, S.; Hamedi-Shahraki, S.; Amirkhizi, F.; Bideshki, M.V.; Harooni, J.; Asghari, S. Association of dietary inflammatory index with dyslipidemia and atherogenic indices in Iranian adults: A cross-sectional study from the PERSIAN dena cohort. Nutr. J. 2025, 24, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Lleó, A.M.; Brito-Casillas, Y.; Martín-Santana, V.; Gil-Quintana, Y.; Tugores, A.; Scicali, R.; Riaño, M.; Hernández-Baraza, L.; Jiménez-Monzón, R.; Girona, J.; et al. Glucose metabolism in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia with a founder effect and a high diabetes prevalence: A cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2025, 24, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaresko, J.; Koch, M.; Schulze, M.B.; Nöthlings, U. Ultra-processed food consumption and human health: An umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 835–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Joung, H. Association between the Korean Healthy Diet Score and Metabolic Syndrome: Effectiveness and Optimal Cutoff of the Korean Healthy Diet Score. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, D. Association between dietary patterns and dyslipidemia in Henan rural adults: A cross-sectional study. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 29, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klop, B.; Elte, J.; Cabezas, M. Dyslipidemia in obesity: Mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1218–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassing, H.C.; Surendran, R.P.; Mooij, H.L.; Stroes, E.S.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Dallinga-Thie, G.M. Pathophysiology of hypertriglyceridemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 826–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borén, J.; Taskinen, M.R.; Björnson, E.; Packard, C.J. Metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in health and dyslipidaemia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 577–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, L.; Yu, R.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Proud, C.G.; Jiang, T. Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 2403–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). População Estimada do País Chega a 212,6 Milhões de Habitantes em 2024; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2024. Available online: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/41111-populacao-estimada-do-pais-chega-a-212-6-milhoes-de-habitantes-em-2024 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

| Authors | Equations |

|---|---|

| WHO [16] | BMI: (BM/Ht2) |

| Bergman et al. [17] | BAI: [HC (cm)/Ht (m) √Ht (m)] − 18] |

| WHO [16] | WHR: [WC (cm)/HC (cm)] |

| Hsieh and Yoshinaga [18] | WHtR: [WC (cm)/Ht (cm)] |

| Valdez [19] | CI: [WC (m)/0.109√ (BM/Ht (m))] |

| Variables | % Response | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 100.00 | ||

| Male | 96 | 43.00 | |

| Female | 127 | 57.00 | |

| Age group | 100.00 | ||

| 60–69 years | 89 | 39.90 | |

| 70–79 years | 92 | 41.30 | |

| ≥80 years | 42 | 18.80 | |

| Educational level | 98.20 | ||

| With formal education | 101 | 46.10 | |

| Without formal education | 118 | 53.90 | |

| Marital status | 100.00 | ||

| Married or in a stable relationship | 114 | 51.10 | |

| Divorced/separated | 52 | 23.30 | |

| Widowed | 57 | 25.60 | |

| Skin color | 98.70 | ||

| White | 22 | 10.00 | |

| Non-white | 198 | 90.00 | |

| Income | 99.10 | ||

| ≤1 minimum wage | 191 | 86.40 | |

| >1 minimum wage | 30 | 13.60 | |

| Alcohol consumption | 99.60 | ||

| No | 175 | 78.80 | |

| Yes | 47 | 21.20 | |

| Tobacco use | 100.00 | ||

| No | 187 | 83.90 | |

| Yes | 36 | 16.10 | |

| Level of physical activity | 100.00 | ||

| Sufficient | 127 | 57.00 | |

| Insufficient | 96 | 43.00 | |

| High sedentary behavior | 100.00 | ||

| No | 168 | 75.30 | |

| Yes | 55 | 24.70 | |

| Seeking healthcare services | 100.00 | ||

| ≥2 times/year | 178 | 79.80 | |

| 1 time/year | 19 | 8.50 | |

| Never | 26 | 11.70 | |

| Hypertension | 100.00 | ||

| No | 85 | 38.10 | |

| Yes | 138 | 61.90 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 99.10 | ||

| No | 175 | 78.20 | |

| Yes | 46 | 20.80 |

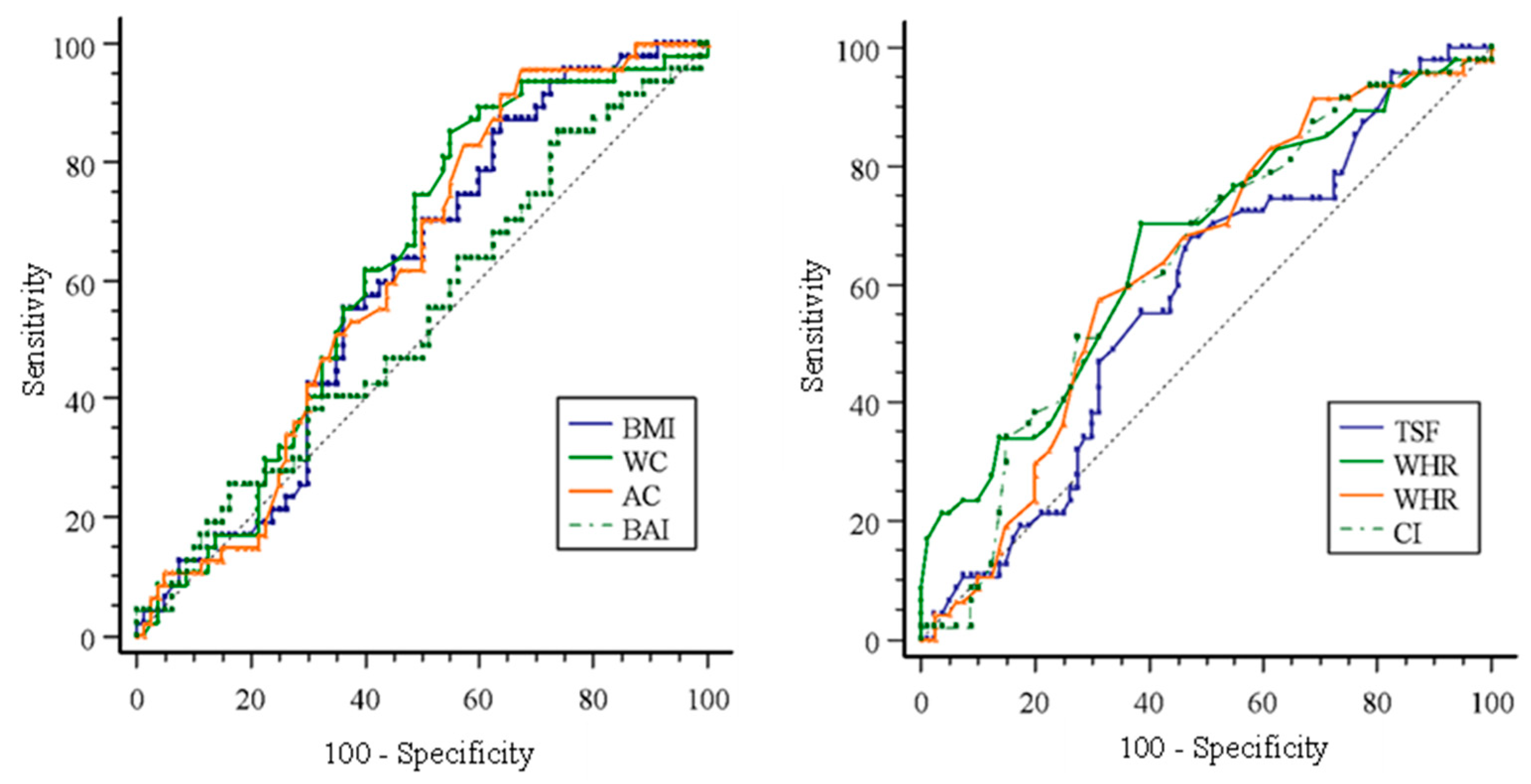

| Older Men | ||||

| Variables | Cutoff Point | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.98 | 51.61 (33.10–69.80) | 76.92 (64.80–86.50) | 0.66 (0.54–0.77) * |

| WC (cm) | 93.00 | 74.19 (55.40–88.20) | 58.46 (45.60–70.60) | 0.66 (0.55–0.78) * |

| AC (cm) | 91.00 | 88.87 (66.30–94.50) | 52.31 (39.50–64.90) | 0.66 (0.55–0.78) * |

| BAI (%) | 27.88 | 51.61 (33.10–69.80) | 70.77 (58.20–81.40) | 0.60 (0.47–0.73) |

| TSF (mm) | 16.00 | 61.29 (42.20–78.20) | 67.69 (54.90–78.80) | 0.65 (0.53–0.76) * |

| WHR | 1.04 | 48.39 (30.20–66.90) | 83.08 (71.70–91.20) | 0.68 (0.57–0.80) * |

| WHtR | 0.59 | 61.29 (42.20–78.20) | 70.77 (58.20–81.40) | 0.66 (0.54–0.78) * |

| CI | 1.33 | 77.42 (58.90–90.40) | 55.38 (42.50–67.70) | 0.62 (0.51–0.73) * |

| Older Women | ||||

| Variables | Cutoff Point | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.48 | 87.23 (74.30–95.20) | 36.25 (25.80–47.80) | 0.60 (0.51–0.70) * |

| WC (cm) | 88.00 | 85.11 (71.70–93.80) | 45.00 (33.80–56.50) | 0.62 (0.53–0.72) * |

| AC (cm) | 89.00 | 95.74 (85.50–99.50) | 32.50 (22.40–43.90) | 0.61 (0.52–0.71) * |

| BAI (%) | 30.41 | 85.11 (71.70–93.80) | 26.25 (17.00–37.30) | 0.53 (0.43–0.64) |

| TSF (mm) | 25.67 | 68.09 (52.90–80.90) | 52.50 (41.00–63.80) | 0.58 (0.48–0.68) |

| WHR | 0.95 | 70.21 (55.10–82.70) | 61.25 (49.70–71.90) | 0.66 (0.56–0.76) * |

| WHtR | 0.64 | 57.45 (42.20–71.70) | 68.75 (57.40–78.70) | 0.63 (0.53–0.73) * |

| CI | 1.38 | 51.06 (36.10–65.90) | 72.50 (61.40–81.90) | 0.64 (0.54–0.73) * |

| Variables | Older Men | ||

| Prevalence (%) | Crude PR (95% CI) | Adjusted PR (95% CI) # | |

| BMI (kg/m2) a | |||

| <26.98 kg/m2 | 23.10 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥26.98 kg/m2 | 51.60 | 2.23 (1.30–3.91) * | 1.90 (1.40–3.40) * |

| WC (cm) b | |||

| <93.00 cm | 17.40 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥93.00 cm | 46.00 | 2.64 (1.32–5.31) * | 2.38 (1.58–7.11) * |

| AC (cm) c | |||

| <91.00 cm | 12.80 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥91.00 cm | 45.60 | 3.55 (1.50–8.50) * | 4.82 (2.03–11.45) * |

| TSF (mm) b | |||

| <16.00 mm | 21.40 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥16.00 mm | 47.50 | 2.21 (1.20–4.03) * | 1.84 (1.05–3.20) * |

| WHR d | |||

| <1.04 | 22.90 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥1.04 | 57.70 | 2.52 (1.47–4.33) * | 2.49 (1.43–4.32) * |

| WHtR e | |||

| <0.59 | 20.70 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥0.59 | 50.00 | 2.41 (1.33–4.38) * | 2.32 (1.27–4.22) * |

| CI f | |||

| <1.33 | 16.30 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥1.33 | 45.30 | 2.78 (1.32–5.82) * | 2.99 (1.32–6.80) * |

| Variables | Older Women | ||

| Prevalence (%) | Crude PR (95% CI) | Adjusted PR (95% CI) # | |

| BMI (kg/m2) g | |||

| <23.48 kg/m2 | 17.10 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥23.48 kg/m2 | 44.60 | 2.60 (1.21–5.58) * | 2.60 (1.24–5.49) * |

| WC (cm) g | |||

| <88.00 cm | 16.30 | 1 | |

| ≥88.00 cm | 47.60 | 2.92 (1.43–5.98) * | 2.85 (1.45–5.58) * |

| AC (cm) g | |||

| <89.00 cm | 7.10 | 1 | |

| ≥89.00 cm | 45.50 | 6.36 (1.64–24.61) * | 6.42 (1.70–24.31) * |

| WHR g | |||

| <0.95 | 22.20 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥0.95 | 51.60 | 2.32 (1.38–3.90) * | 2.06 (1.29–3.45) * |

| WHtR g | |||

| <0.64 | 25.70 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥0.64 | 52.80 | 2.06 (1.30–3.20) * | 1.81 (1.13–2.90) * |

| CI g | |||

| <1.38 | 28.40 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥1.38 | 52.20 | 1.83 (1.18–2.86) * | 1.60 (1.02–2.52) * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolfgang Farias Paiva, M.; de Sousa Miranda, C.F.; Alves Godinho, G.; Dutra Lopes, C.D.; Souza Queiroz, T.; Jesus da Silva, D.; da Silva Caires, S.; Valença Neto, P.d.F.; Bispo de Almeida, C.; Casotti, C.A.; et al. Anthropometric Indicators of Obesity as Screening Tools for Hypertriglyceridemia in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Obesities 2025, 5, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040093

Wolfgang Farias Paiva M, de Sousa Miranda CF, Alves Godinho G, Dutra Lopes CD, Souza Queiroz T, Jesus da Silva D, da Silva Caires S, Valença Neto PdF, Bispo de Almeida C, Casotti CA, et al. Anthropometric Indicators of Obesity as Screening Tools for Hypertriglyceridemia in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Obesities. 2025; 5(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolfgang Farias Paiva, Max, Caio Felipe de Sousa Miranda, Gabriel Alves Godinho, Carlos Daniel Dutra Lopes, Tony Souza Queiroz, Débora Jesus da Silva, Sabrina da Silva Caires, Paulo da Fonseca Valença Neto, Claudio Bispo de Almeida, Cezar Augusto Casotti, and et al. 2025. "Anthropometric Indicators of Obesity as Screening Tools for Hypertriglyceridemia in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study" Obesities 5, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040093

APA StyleWolfgang Farias Paiva, M., de Sousa Miranda, C. F., Alves Godinho, G., Dutra Lopes, C. D., Souza Queiroz, T., Jesus da Silva, D., da Silva Caires, S., Valença Neto, P. d. F., Bispo de Almeida, C., Casotti, C. A., Cardoso Roriz, B., Pereira Santos, F. D. R., Franco, O. L., Buccini, D. F., Barros Fernandes, A., Ferreira Silva Pinheiro, H. D., & dos Santos, L. (2025). Anthropometric Indicators of Obesity as Screening Tools for Hypertriglyceridemia in Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Obesities, 5(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5040093