“Super-Responders” to Liraglutide Monotherapy and the Growing Evidence of Efficacy of GLP-1 Analogues in Obesity Management: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Subjects, Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients and Their Weight Status at Baseline

3.2. Adherence with Treatment and Lifestyle Modifications Recommendations

3.3. Benefits and Side Effects of Liraglutide

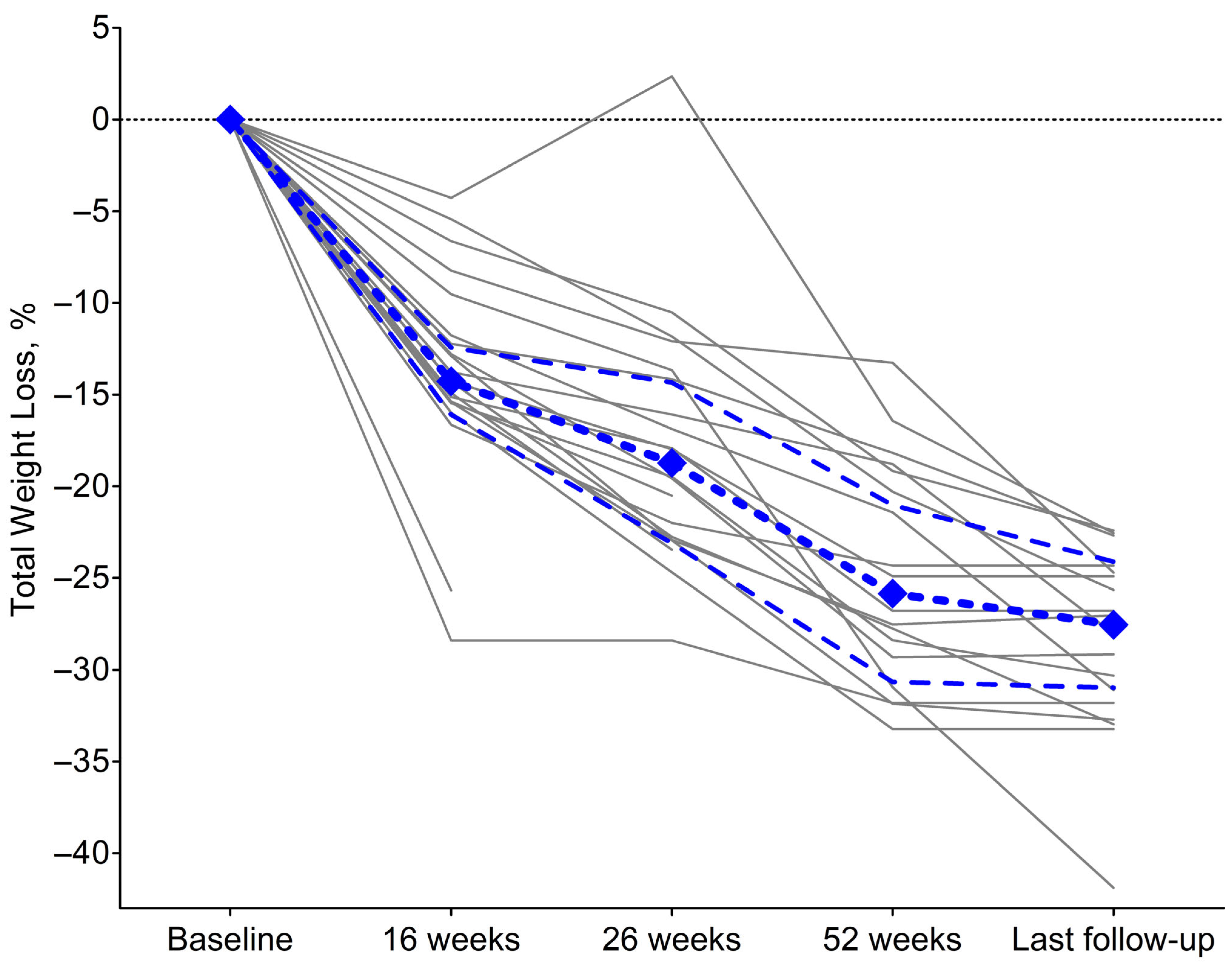

3.4. Changes in Weight Status During Treatment

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- GBD 2021 Adult BMI Collaborators. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytvyak, E.; Straube, S.; Modi, R.; Lee, K.K. Trends in Obesity across Canada from 2005 to 2018: A Consecutive Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study. CMAJ Open 2022, 10, E439–E449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guh, D.P.; Zhang, W.; Bansback, N.; Amarsi, Z.; Birmingham, C.L.; Anis, A.H. The Incidence of Co-Morbidities Related to Obesity and Overweight: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, A.; Pisani, P.; Tenet, V.; Wolk, A.; Adami, H.O. Overweight as an Avoidable Cause of Cancer in Europe. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 91, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotnikoff, R.; Karunamuni, N.; Lytvyak, E.; Penfold, C.; Schopflocher, D.; Imayama, I.; Johnson, S.T.; Raine, K. Osteoarthritis Prevalence and Modifiable Factors: A Population Study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Avenell, A.; Bolland, M.; Hudson, J.; Stewart, F.; Robertson, C.; Sharma, P.; Fraser, C.; MacLennan, G. Effects of Weight Loss Interventions for Adults Who Are Obese on Mortality, Cardiovascular Disease, and Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2017, 359, j4849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rijswijk, A.-S.; van Olst, N.; Schats, W.; van der Peet, D.L.; van de Laar, A.W. What Is Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery Expressed in Percentage Total Weight Loss (%TWL)? A Systematic Review. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 3833–3847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroda, V.R. A Review of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Evolution and Advancement, Through the Lens of Randomised Controlled Trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20 (Suppl. S1), 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.F.E.; Hansen, T.; Idorn, T.; Leiter, L.A.; Marso, S.P.; Rossing, P.; Seufert, J.; Tadayon, S.; Vilsbøll, T. Effects of Once-Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide on Kidney Function and Safety in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Post-Hoc Analysis of the SUSTAIN 1–7 Randomised Controlled Trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 880–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi-Sunyer, X.; Astrup, A.; Fujioka, K.; Greenway, F.; Halpern, A.; Krempf, M.; Lau, D.C.W.; le Roux, C.W.; Violante Ortiz, R.; Jensen, C.B.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of 3.0 mg of Liraglutide in Weight Management. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Tronieri, J.S.; Sugimoto, D.; Lund, M.T.; Auerbach, P.; Jensen, C.; Rubino, D. Liraglutide 3.0 mg and Intensive Behavioral Therapy (IBT) for Obesity in Primary Care: The SCALE IBT Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity 2020, 28, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Bailey, T.S.; Billings, L.K.; Davies, M.; Frias, J.P.; Koroleva, A.; Lingvay, I.; O’Neil, P.M.; Rubino, D.M.; Skovgaard, D.; et al. Effect of Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo as an Adjunct to Intensive Behavioral Therapy on Body Weight in Adults with Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastreboff, A.M.; Aronne, L.J.; Ahmad, N.N.; Wharton, S.; Connery, L.; Alves, B.; Kiyosue, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, B.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, P.M.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; McGowan, B.; Mosenzon, O.; Pedersen, S.D.; Wharton, S.; Carson, C.G.; Jepsen, C.H.; Kabisch, M.; Wilding, J.P.H. Efficacy and Safety of Semaglutide Compared with Liraglutide and Placebo for Weight Loss in Patients with Obesity: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo and Active Controlled, Dose-Ranging, Phase 2 Trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrén, B.; Atkin, S.L.; Charpentier, G.; Warren, M.L.; Wilding, J.P.H.; Birch, S.; Holst, A.G.; Leiter, L.A. Semaglutide Induces Weight Loss in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes Regardless of Baseline BMI or Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in the SUSTAIN 1 to 5 Trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2018, 20, 2210–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, W.T.; Frias, J.P.; Jastreboff, A.M.; le Roux, C.W.; Sattar, N.; Aizenberg, D.; Mao, H.; Zhang, S.; Ahmad, N.N.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Tirzepatide Once Weekly for the Treatment of Obesity in People with Type 2 Diabetes (SURMOUNT-2): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Multicentre, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez Medina, S.; Sánchez Campayo, E.; Guadalix, S.; Escalada, J. Super Response to Liraglutide in People with Obesity: A Case Report and Literature Review. Endocrinol. Diabetes Y Nutr. 2024, 71, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.M.; Kushner, R.F. A Proposed Clinical Staging System for Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, A.; Maldonado, J.M.; Wang, H.U.I.; Rasouli, N.; Wilding, J. 719-P: Tirzepatide Induces Weight Loss in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Regardless of Baseline BMI: A Post Hoc Analysis of SURPASS-1 through -5 Studies. Diabetes 2022, 71 (Suppl. S1), 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, M.; Wang, R.; Du, L.; Ji, L. Efficacy and Safety of Tirzepatide in People with Type 2 Diabetes by Baseline Body Mass Index: An Exploratory Subgroup Analysis of SURPASS-AP-Combo. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 1454–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- le Roux, C.; Aroda, V.; Hemmingsson, J.; Cancino, A.P.; Christensen, R.; Pi-Sunyer, X. Comparison of Efficacy and Safety of Liraglutide 3.0 mg in Individuals with BMI above and below 35 Kg/M2: A Post-Hoc Analysis. Obes. Facts 2017, 10, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, K.; O’Neil, P.M.; Davies, M.; Greenway, F.; Lau, D.C.W.; Claudius, B.; Skjøth, T.V.; Bjørn Jensen, C.; Wilding, J.P.H. Early Weight Loss with Liraglutide 3.0 mg Predicts 1-Year Weight Loss and Is Associated with Improvements in Clinical Markers. Obesity 2016, 24, 2278–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadegiani, F.A.; Diniz, G.C.; Alves, G. Aggressive Clinical Approach to Obesity Improves Metabolic and Clinical Outcomes and Can Prevent Bariatric Surgery: A Single Center Experience. BMC Obes. 2017, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilding, J.P.H.; Batterham, R.L.; Calanna, S.; Davies, M.; Van Gaal, L.F.; Lingvay, I.; McGowan, B.M.; Rosenstock, J.; Tran, M.T.D.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Once-Weekly Semaglutide in Adults with Overweight or Obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhassan, S.; Kim, S.; Bersamin, A.; King, A.C.; Gardner, C.D. Dietary Adherence and Weight Loss Success among Overweight Women: Results from the A to Z Weight Loss Study. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Neiberg, R.H.; Wing, R.R.; Clark, J.M.; Delahanty, L.M.; Hill, J.O.; Krakoff, J.; Otto, A.; Ryan, D.H.; Vitolins, M.Z.; et al. Four-Year Weight Losses in the Look AHEAD Study: Factors Associated with Long-Term Success. Obesity 2011, 19, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Færch, L.; Jeppesen, O.K.; Pakseresht, A.; Pedersen, S.D.; Perreault, L.; Rosenstock, J.; Shimomura, I.; Viljoen, A.; Wadden, T.A.; et al. Semaglutide 2 4 mg Once a Week in Adults with Overweight or Obesity, and Type 2 Diabetes (STEP 2): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.; Bailey, T.; Billings, L.; Frias, J.; Koroleva, A.; O’Neil, P.; Rubino, D.; Skovgaard, D.; Wallenstein, S.; Garvey, W.T. Semaglutide 2.4 mg and Intensive Behavioral Therapy in Subjects with Overweight or Obesity (STEP 3). In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of The Obesity Society (TOS) Held at ObesityWeek®, Online, 2–6 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rubino, D.; Abrahamsson, N.; Davies, M.; Hesse, D.; Greenway, F.L.; Jensen, C.; Lingvay, I.; Mosenzon, O.; Rosenstock, J.; Rubio, M.A.; et al. Effect of Continued Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Placebo on Weight Loss Maintenance in Adults with Overweight or Obesity: The STEP 4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoff, A.M.; Brown-Frandsen, K.; Colhoun, H.M.; Deanfield, J.; Emerson, S.S.; Esbjerg, S.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.; Hovingh, G.K.; Kahn, S.E.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Chao, A.M.; Machineni, S.; Kushner, R.; Ard, J.; Srivastava, G.; Halpern, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, J.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Author Correction: Tirzepatide After Intensive Lifestyle Intervention in Adults with Overweight or Obesity: The SURMOUNT-3 Phase 3 Trial. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronne, L.J.; Sattar, N.; Horn, D.B.; Bays, H.E.; Wharton, S.; Lin, W.-Y.; Ahmad, N.N.; Zhang, S.; Liao, R.; Bunck, M.C.; et al. Continued Treatment with Tirzepatide for Maintenance of Weight Reduction in Adults with Obesity: The SURMOUNT-4 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024, 331, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, K.; Telesford, I.; Singh, R.; Cox, C. Health System Tracker: How Do Prices of Drugs for Weight Loss in the U.S. Compare to Peer Nations’ Prices? Available online: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/how-do-prices-of-drugs-for-weight-loss-in-the-u-s-compare-to-peer-nations-prices (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Buntz, B. Teva Readies First Generic Version of GLP-1 Drug Victoza in U.S. Available online: https://www.drugdiscoverytrends.com/teva-launches-first-generic-glp1-drug-us-market/#:~:text=Teva%20introduces%20first%20U.S.%20generic,space%2C%E2%80%9D%20a%20spokesperson%20said (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- O’Brien, P.E.; Hindle, A.; Brennan, L.; Skinner, S.; Burton, P.; Smith, A.; Crosthwaite, G.; Brown, W. Long-Term Outcomes After Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Weight Loss at 10 or More Years for All Bariatric Procedures and a Single-Centre Review of 20-Year Outcomes After Adjustable Gastric Banding. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obesity Canada-Obésité Canada. Report Card on Access to Obesity Treatment for Adults in Canada 2019; Springer: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald, H.; Oien, D.M. Metabolic/Bariatric Surgery Worldwide 2011. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, M.; Wharton, S.; Macpherson, A.; Kuk, J.L. Receptivity to Bariatric Surgery in Qualified Patients. J. Obes. 2016, 2016, 5372190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, R.; Febres, G.; Cheng, B.; Krikhely, A.; Bessler, M.; Korner, J. Prospective Study of Gut Hormone and Metabolic Changes After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, J.J.; Madsbad, S.; Bojsen-Møller, K.N.; Svane, M.S.; Jørgensen, N.B.; Dirksen, C.; Martinussen, C. Mechanisms in Bariatric Surgery: Gut Hormones, Diabetes Resolution, and Weight Loss. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2018, 14, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytvyak, E.; Zarrinpar, A.; Dalle Ore, C.; Lee, E.; Yazdani-Boset, K.; Hordan, S.; Grunvald, E. Control of Eating Attributes and Weight Loss Outcomes over One Year After Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 1618–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Docimo, S.; Shah, J.; Warren, G.; Ganam, S.; Sujka, J.; DuCoin, C. A Cost Comparison of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists and Bariatric Surgery: What Is the Break Even Point? Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 6560–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Nagendra, L.; Joshi, A.; Krishnasamy, S.; Sharma, M.; Parajuli, N. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists in Post-Bariatric Surgery Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 1653–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, P.; Modi, R.; Cawsey, S.; Sharma, A.M. Efficacy of High-Dose Liraglutide as an Adjunct for Weight Loss in Patients with Prior Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 3553–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, J.; Adeleke, M.O.; Brown, A.; Magee, C.G.; Firman, C.; Makahamadze, C.; Jassil, F.C.; Marvasti, P.; Carnemolla, A.; Devalia, K.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Liraglutide, 3.0 mg, Once Daily vs Placebo in Patients with Poor Weight Loss Following Metabolic Surgery: The BARI-OPTIMISE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2023, 158, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, S.; Lee, J.; Christensen, R.A.G. Weight Loss Medications in Canada—A New Frontier or a Repeat of Past Mistakes? Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, S.; Lau, D.C.W.; Vallis, M.; Sharma, A.M.; Biertho, L.; Campbell-Scherer, D.; Adamo, K.; Alberga, A.; Bell, R.; Boulé, N.; et al. Obesity in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2020, 192, E875–E891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, W.T.; Mechanick, J.I.; Brett, E.M.; Garber, A.J.; Hurley, D.L.; Jastreboff, A.M.; Nadolsky, K.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Plodkowski, R. American association of clinical endocrinologists and american college of endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr. Pract. 2016, 22 (Suppl. S3), 1–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadden, T.A.; Walsh, O.A.; Berkowitz, R.I.; Chao, A.M.; Alamuddin, N.; Gruber, K.; Leonard, S.; Mugler, K.; Bakizada, Z.; Tronieri, J.S. Intensive Behavioral Therapy for Obesity Combined with Liraglutide 3.0 mg: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity 2019, 27, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Median (IQR) or % (n) n = 21 |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Female sex | 90.5% (19) |

| Age at liraglutide initiation, years | 50 (17) |

| Age ≥ 50 years old at liraglutide initiation | 52.4% (11) |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 90.5% (19) |

| Weight Status | |

| Peak weight, kg | 127.6 (34.7) |

| Peak BMI, kg/m2 | 48.0 (17.1) |

| Class II or III obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) | 100% (21) |

| BMI ≥ 50 kg/m2 | 42.9% (9) |

| EOSS stage | |

| 0 | 0% (0) |

| 1 | 4.8% (1) |

| 2 | 90.5% (19) |

| 3 | 4.8% (1) |

| 4 | 0% (0) |

| Medical History | |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 57.1% (12) |

| Hypothyroidism | 42.9% (9) |

| Hypertension | 42.9% (9) |

| Osteoarthritis | 28.6% (6) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 23.8% (5) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 23.8% (5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 23.8% (5) |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome a | 15.8% (3) |

| Endometrial cancer a | 10.5% (2) |

| History of pulmonary embolism/deep vein thrombosis | 9.5% (2) |

| Steatotic liver disease | 9.5% (2) |

| Mental Health History and Psychological Evaluation | |

| MDD | 42.9% (9) |

| GAD | 23.8% (5) |

| Binge eating disorder | 9.5% (2) |

| ADHD | 9.5% (2) |

| Personality disorder | 4.8% (1) |

| History of abuse, incl. sexual, physical, emotional | 28.6% (6) |

| History of addiction, incl. alcohol, recreational drugs | 9.5% (2) |

| Bariatric Surgery-related | |

| History of bariatric surgery before liraglutide initiation | 14.3% (3) |

| Interested in bariatric surgery | 66.7% (14) |

| Proceeded with bariatric surgery post-liraglutide treatment, out of those interested | 78.6% (11) |

| Type of bariatric surgery performed | |

| Roux-en-Y gastric bypass | 54.5% (6) |

| Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy | 45.5% (5) |

| Parameter | Median (IQR) or % (n) |

|---|---|

| Pre-treatment (n = 21) | |

| Weight, at liraglutide initiation (baseline), kg | 123.6 (34.9) |

| BMI, at liraglutide initiation, kg/m2 | 45.7 (7.4) |

| At their peak weight, at liraglutide initiation | 47.6% (10) |

| Lifestyle Modifications (n = 21) | |

| Consistently tracking calorie intake | 95.2% (20) |

| Consistently tracking protein intake | 90.5% (19) |

| Established regulated meal pattern | 85.7% (18) |

| Calorie deficit achieved, kcal per day | −651 (−323) |

| Met protein target | 85.7% (18) |

| Engaged in regular physical activity as tolerated | 80.9% (17) |

| Treatment Outcomes—Weight Status | |

| 16 weeks (n = 21) | |

| Weight, kg | 109.1 (23.3) |

| Total Weight Loss, % from the baseline | 14.3% (3.7) |

| 26 weeks (n = 20) | |

| Weight, kg | 99.3 (19.6) |

| Total Weight Loss, % from the baseline | 18.7% (8.8) |

| 52 weeks (n = 18) | |

| Weight, kg | 91.3 (18.4) |

| Total Weight Loss, % from the baseline | 25.9% (9.6) |

| Last follow-up (n = 18) | |

| Weight, kg | 87.7 (16.1) |

| Total Weight Loss, % from the baseline | 27.5% (7.4) |

| Benefits * | |

| Appetite reduction | 95.2% (20) |

| Smaller portions | 95.2% (20) |

| Healthier food choices | 90.5% (19) |

| Increased satiety | 81.0% (17) |

| Lower frequency and intensity of cravings | 66.7% (14) |

| Improved control over eating | 19.0% (4) |

| Decreased food pre-occupation | 14.3% (3) |

| Adverse events * | |

| GI-related | |

| Constipation | 47.6% (10) |

| Nausea | 42.9% (9) |

| Dysgeusia | 33.3% (7) |

| Belching | 14.3% (3) |

| Dyspepsia | 14.3% (3) |

| Systemic | |

| Headache | 23.8% (5) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lytvyak, E.; Grunvald, E.; Shreekumar, D.; Rye, P.; Troshyn, O.; Cawsey, S.; Montano-Loza, A.J.; Sharma, A.M.; Modi, R. “Super-Responders” to Liraglutide Monotherapy and the Growing Evidence of Efficacy of GLP-1 Analogues in Obesity Management: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Obesities 2025, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030063

Lytvyak E, Grunvald E, Shreekumar D, Rye P, Troshyn O, Cawsey S, Montano-Loza AJ, Sharma AM, Modi R. “Super-Responders” to Liraglutide Monotherapy and the Growing Evidence of Efficacy of GLP-1 Analogues in Obesity Management: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Obesities. 2025; 5(3):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030063

Chicago/Turabian StyleLytvyak, Ellina, Eduardo Grunvald, Devika Shreekumar, Peter Rye, Olexandr Troshyn, Sarah Cawsey, Aldo J. Montano-Loza, Arya M. Sharma, and Renuca Modi. 2025. "“Super-Responders” to Liraglutide Monotherapy and the Growing Evidence of Efficacy of GLP-1 Analogues in Obesity Management: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study" Obesities 5, no. 3: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030063

APA StyleLytvyak, E., Grunvald, E., Shreekumar, D., Rye, P., Troshyn, O., Cawsey, S., Montano-Loza, A. J., Sharma, A. M., & Modi, R. (2025). “Super-Responders” to Liraglutide Monotherapy and the Growing Evidence of Efficacy of GLP-1 Analogues in Obesity Management: A Longitudinal Prospective Cohort Study. Obesities, 5(3), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5030063