Weight Stigma in Physical and Occupational Therapy: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

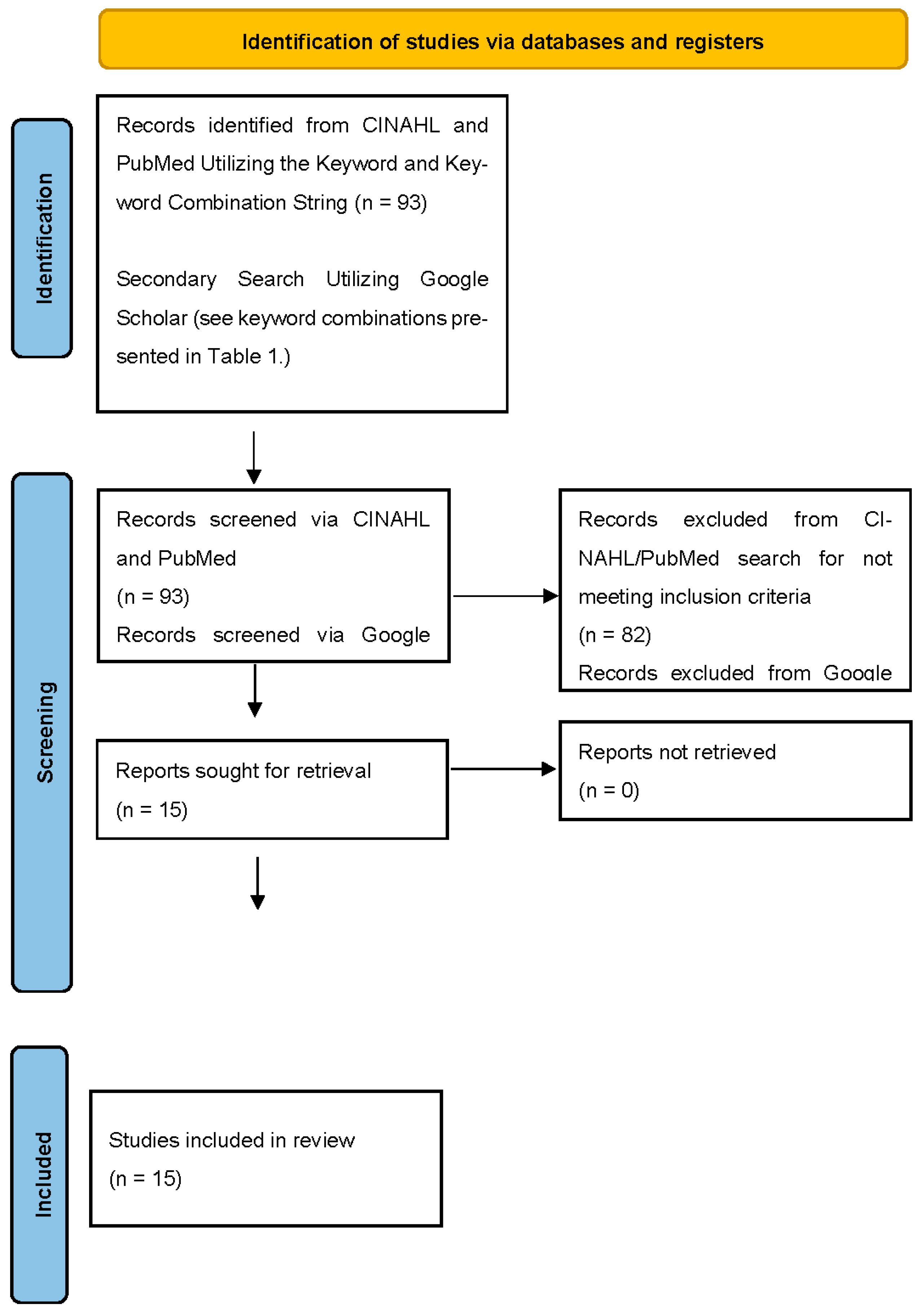

2. Materials and Methods

| Scale | Description | Interpretation of Scores |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-fat Attitudes Questionnaire [43,44,45] | 13-item tool utilizing a 10-point Likert scale. Subjects rate statements regarding individuals who are overweight or with obesity (0 = very strongly disagree to 9 = very strongly agree). | Total and subdomain scores are calculated Scores above 0 identify anti-fat bias |

| Attitudes Towards Obese Persons Scale (ATOP) [46,47] | 20-item tool utilizing a 6-point Likert scale. Questions assess one’s agreement or disagreement with a statement (range +3 “agree” to −3 “disagree”). Scores range from 0 to 120. | Scores of 61 to 120 indicate a positive attitude toward people with obesity |

| Attitudes Toward Obesity—Prejudicial Evaluation and Social Interaction Scale (AO-PESIS) [48] | 22-item tool utilizing 10-point Likert scale Assesses healthcare provider prejudicial attitudes. The two subscales are prejudicial evaluation and social interaction. Scores range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). | Higher total or subscale scores indicated a greater negative attitude toward people with obesity |

| Beliefs About Obese Persons (BAOP) [46] | Eight-item tool utilizing a six-point Likert-type scale (scores range from −3 “I strongly disagree” to +3 “I strongly agree”). Scores range from 0 to 48. | Higher scores indicate one believes that obesity is not under control of the patient |

| Fat Attitudes Assessment Toolkit [49] | 49-item tool utilizing a 7-point Likert scale. Scores range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The survey has five subscales, two complexity scales, two composite scores, and two independent domains. | Lower scores are associated with a negative view of individuals with obesity Higher subscale scores [49]: Fat acceptance subscale = “beliefs that are positive toward fat people” Complexity scales = “beliefs that factors beyond an individual control contribute to fatness” Responsibility subscale = “respondents do not attribute fatness to be an individual’s responsibility” Self-reflection subscale = “appraisal of own body weight…with higher scores indicating positive self-assessment” |

| Fat Phobia Scale [50] | 14-item tool utilizing 5-point Likert scale. | Scores above 2.5 are associated with weight stigma, with higher scores indicating greater bias |

| Modified Weight Bias Internalization Scale [51] | 11-item tool utilizing a 7-item Likert scale (range: strongly agree to strongly disagree). Average scores range from 1 to 7. | Higher scores are associated with internalized weight bias |

| NEW (Nutrition, Exercise, and Weight management) Attitudes Scale [52] | 31-item tool utilizing a 5-point Thurstone scale. Items are related to exercise, nutrition, weight management, and non-specific domains. Scores range from −118 to 118. | Higher scores indicate positive attitude toward people with obesity |

| Perceived Weight Bias in Healthcare [47,53] | 7-item tool utilizing a 5-point Likert-scale. Assesses one’s perception of weight bias in their peers, teachers, and clinicians (range: strongly agree to strongly disagree). | |

| Weight Implicit Association Test [54] | Scores determine strength of preference for fat or thin people. Scores range from −2.0 to 2.0. | −0.14 to 0.14, no preference 0.15 to 0.34, slight preference for thin people 0.35 to 0.64, moderate preference for thin people 0.65 or higher, strong preference for thin people |

3. Results

3.1. Weight Stigma Scores for Physical Therapy Professionals

3.2. Weight Stigma Scores Post Intervention in Physical Therapy Professionals

3.3. Weight Stigma Scores for Occupational Therapy Professionals

3.4. Weight Stigma Scores Post Intervention in Occupational Therapy Professionals

4. Discussion

4.1. Weight Stigma in Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy Professionals and Students

4.2. Educational Interventions for Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy Professionals and Students

4.3. Effectiveness of Interventions to Reduce Weight Stigma in Healthcare Professionals

4.4. Strengths and Weaknesses of Current Studies

4.5. Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFA | Anti-Fat Attitudes Questionnaire |

| ATOP | Attitudes Towards Obese Persons Scale |

| AO-PESIS | Attitudes Toward Obesity—Prejudicial Evaluation and Social Interaction Scale |

| BAOPs | Beliefs About Obese Persons |

| FAAT | Fat Attitudes Assessment Toolkit |

| PT | Physical Therapy or Physical Therapist or Physiotherapist |

| OT | Occupational Therapy or Occupational Therapist |

| NEW | Nutrition, Exercise, and Weight management |

| WIAT | Weight Implicit Association Test |

References

- Berryman, D.E.; Dubale, G.M.; Manchester, D.S.; Mittelstaedt, R. Dietetics students possess negative attitudes toward obesity similar to nondietetics students. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1678–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, I. Nurses’s attitudes towards adult patients who are obese: Literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 53, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creel, E.; Tillman, K. Stigmatization of overweight patients by nurses. Qual. Rep. 2011, 16, 1330–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, J.M.; Seaman, K.; Bator, A.; Ohman-Strickland, P.; Gundersen, D.; Clemow, L.; Puhl, R. Impact of perceived weight stigma among underserved women on doctor-patient relationships. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2016, 2, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.P., Jr.; Spangler, J.G.; Vitolins, M.Z.; Davis, S.W.; Ip, E.H.; Marion, G.S.; Crandall, S.J. Are medical students aware of their anti-obesity bias? Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, G.A.; Armstrong, L.E.; Taylor, B.A.; Puhl, R.M.; Livingston, J.; Pescatello, L.S. Weight bias among exercise and nutrition professionals: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1492–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, J.A.; Panza, E.A.; Selby, E.; Feinstein, B. Lifetime and daily weight stigma among higher weight sexual minority women: Links to daily weight-based concerns, avoidance, and negative affect. Stigma Health 2024, 9, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, E.; Olson, K.; Goldstein, C.M.; Selby, E.A.; Lillis, J. Characterizing lifetime and daily experiences of weight stigma among sexual minority women with overweight and obesity: A descriptive study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, G.A.; Puhl, R.M.; Taylor, B.A.; Zaleski, A.L.; Livingston, J.; Pescatello, L.S. Links between discrimination and cardiovascular health among socially stigmatized groups: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e021763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, A.M.; Flint, S.W.; Clare, K.; Kousoulis, A.A.; Rothwell, E.R.; Bould, H.; Howe, L.D. Demographic, socioeconomic and life-course risk factors for internalized weight stigma in adulthood: Evidence from an English birth cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 15, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnick, J.L.; Darling, K.E.; West, C.E.; Jones, L.; Jelalian, E. Weight stigma and mental health in youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 5, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearl, R.L.; Groshon, L.C.; Hernandez, M.; Bach, C.; LaFata, E.M.; Fitterman-Harris, H.F.; Leget, D.L.; Sheynblyum, M.; Wadden, T.A. Characterising first, recent and worst experiences of weight stigma in a clinical sample of adults with high body weight and high internalised stigma. Clin. Obes. 2025, 3, e70005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Brownell, K.D. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: An investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity 2006, 14, 1802–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; King, K.M. Weight discrimination and bullying. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 27, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, S.M.; Dovidio, J.F.; Puhl, R.M.; Burgess, D.J.; Nelson, D.B.; Yeazel, M.W.; Hardeman, R.; Perry, S.; van Ryn, M. Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4,732 medical students: The medical student CHANGES study. Obesity 2014, 22, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, B.J.; Deborah, K.; Pollard, C.M.; Theophilus, M.; Alexander, E.; Haywood, D.; O’Connor, M. Weight bias among health care professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity 2021, 29, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, K.; Engel, H.; Timperio, A.; Cooper, C.; Crawford, D. Obesity management: Australian general practitioners’ attitudes and practices. Obes. Res. 2000, 8, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.; Brownell, K.D. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes. Res. 2001, 9, 788–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertakis, K.D.; Azari, R. The impact of obesity on primary care visits. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquier, A.; Verger, P.; Basdevant, A.; Andreotti, G.; Baretge, J.; Villani, P.; Paraponaris, A. Overweight and obesity: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of general practitioners in France. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persky, S.; Eccleston, C.P. Medical student bias and care recommendations for an obese versus non-obese virtual patient. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amy, N.K.; Aalborg, A.; Lyons, P.; Keranen, L. Barriers to routine gynecological cancer screening for White and African-American obese women. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudzune, K.A.; Bennett, W.L.; Cooper, L.A.; Bleich, S.N. Perceived judgment about weight can negatively influence weight loss: A cross-sectional study of overweight and obese patients. Prev. Med. 2014, 62, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudzune, K.A.; Bennett, W.L.; Cooper, L.A.; Bleich, S.N. Patients who feel judged about their weight have lower trust in their primary care providers. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 97, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Latner, J.D. Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation’s children. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Peterson, J.L.; Luedicke, J. Weight-based victimization: Bullying experiences of weight loss treatment-seeking youth. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchianeri, M.M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Body dissatisfaction: An overlooked public health concern. J. Public Ment. Health 2014, 13, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madowitz, J.; Knatz, S.; Maginot, T.; Crow, S.J.; Boutelle, K.N. Teasing, depression and unhealthy weight control behaviour in obese children. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 7, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonneville, K.R.; Thurston, I.B.; Gordon, A.R.; Richmond, T.K.; Weeks, H.M.; Lipson, S.K. Weight stigma associated with mental health concerns among college students. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 66, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timkova, V.; Mikula, P.; Nagyova, I. Psychological distress in people with overweight and obesity: The role of weight stigma and social support. Front. Psychol. 2025, 15, 1474844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Terracciano, A. Perceived weight discrimination and obesity. PLoS ONE 2013, 24, e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.E.; Steptoe, A.; Beeken, R.J.; Kivimaki, M.; Wardle, J. Psychological changes following weight loss in overweight and obese adults: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Stephan, Y.; Luchetti, M.; Terracciano, A. Perceived weight discrimination and C-reactive protein. Obesity 2014, 22, 1959–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, J.M.; Major, B. Weight stigma mediates the association between BMI and self-reported health. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Stephan, Y.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Robinson, E.; Daly, M.; Terracciano, A. Perceived weight discrimination, changes in health, and daily stressors. Obesity 2016, 24, 2202–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schvey, N.A.; Puhl, R.M.; Brownell, K.D. The impact of weight stigma on caloric consumption. Obesity 2011, 19, 1957–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, C.; Leclair, L.; Hand, C.; Wener, P.; Letts, L. Occupational therapy services in primary care: A scoping review. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2023, 24, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.K.; Rothberg, M.B.; Adams, K.; Lapin, B.; Keeney, T.; Stilphen, M.; Bethoux, F.; Freburger, J.K. Association of physical therapy treatment frequency in the acute care hospital with improving functional status and discharging home. Med. Care 2022, 60, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodoehl, J.; Kraus, S.; Stein, A.B. Predicting the number of physical therapy visits and patient satisfaction in individuals with temporomandibular disorder: A cohort study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 49, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.Y.; Trivedi, A.N.; Grabowski, D.C.; Mor, V. Does more therapy in skilled nursing facilities lead to better outcomes with hip fracture? Phys. Ther. 2015, 96, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusynski, R.A.; Gustavson, A.M.; Shrivastav, S.R.; Mroz, T.M. Rehabilitation intensity and patient outcomes in skilled nursing facilities in the United States: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzaa230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchell, J.; Watson, B.; Jones, L.; Gard, M.; Briffa, K. Physiotherapists demonstrate weight stigma: A cross-sectional survey of Australian physiotherapists. J. Physiother. 2014, 60, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crandall, C.S. Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elboim-Gabyzon, M.; Attar, K.; Peleg, S. Weight Stigmatization among Physical Therapy Students and Registered Physical Therapists. Obes. Facts. 2020, 13, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, D.B.; Basile, V.C.; Yuker, H.E. The measurement of attitudes toward and beliefs about obese persons. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991, 10, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, G.; McMahon, S.; Holt, A.; Nedai, M.; Nybo, T.; Peiris, C.L. Obesity bias and stigma, attitudes and beliefs among entry-level physiotherapy students in the Republic of Ireland: A cross sectional study. Physiotherapy 2021, 112, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroman, K.; Cote, S. Prejudicial attitudes toward clients who are obese: Measuring implicit attitudes of occupational therapy students. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2011, 25, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, P.; Donaghue, N.; Ditchburn, G. Development and validation of the Fat Attitudes Assessment Toolkit (FAAT): A multidimensional nonstigmatizing measure of contemporary attitudes toward fatness and fat people. J. Appl. Social Psych. 2022, 52, 1121–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B.E.; Bacon, J.G.; O’Reilly, J. Fat phobia: Measuring, understanding, and changing anti-fat attitudes. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1993, 14, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R.L.; Puhl, R.M. Measuring internalized weight attitudes across body weight categories: Validation of the modified weight bias internalization scale. Body Image. 2014, 11, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, E.H.; Marshall, S.; Vitolins, M.; Crandall, S.J.; Davis, S.; Miller, D.; Kronner, D.; Vaden, K.; Spangler, J. Measuring medical student attitudes and beliefs regarding patients who are obese. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhl, R.M.; Luedicke, J.; Grilo, C.M. Obesity bias in training: Attitudes, beliefs, and observations among advanced trainees in professional health disciplines. Obesity 2014, 22, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A.G.; Nosek, B.A.; Banaji, M.R. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. J. Pers. Soc. Psych. 2003, 85, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchell, J.; Watson, B.M.; Gard, M.; Jones, L. Physical therapists’ ways of talking about overweight and obesity: Clinical implications. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.A.; Forhan, M. Addressing weight bias and stigma of obesity amongst physiotherapists. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2021, 37, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, C.; Feldner, H.; VanPuymbrouck, L. Anti-fat biases of occupational and physical therapy assistants. Occup. Ther. Health Care 2022, 36, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, A.J.; Ng, C.L.W.; Lim, C.J.; Jones, L.E.; Lee, Y.; Tham, K.W. Qualified and student healthcare professionals in Singapore display explicit weight bias. A cross-sectional survey. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 18, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rompolski, K.; Pascoe, M.A. Does dissection influence weight bias among doctor of physical therapy students? Anat. Sci. Educ. 2024, 17, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, S.C.; Thille, P.; Liu, K.; Wittmeier, K.; Cain, P. Determining associations among health orientation, fitness orientation, and attitudes toward fatness in physiotherapists and physiotherapy students using structural equation modeling. Physiother. Can. 2024, 76, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forhan, M.; Law, M. An Evaluation of a Workshop about Obesity Designed for Occupational Therapists. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2009, 76, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemhuis, K.; Cozzolino, M. Obesity, stigma, and occupational therapy. Phys. Disabil. Spec. Interest Q. 2010, 33, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, C.; VanPuymbrouck, L.H. Anti-fat bias of occupational therapy students. J. Occup. Ther. Educ. 2019, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, A.; Foy, M.; White, C. Working with clients of higher weight in Australia: Findings from a national survey exploring occupational therapy practice. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2022, 69, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, K.; Beattie, O.; Hitch, D.; Pepin, G. Occupational therapy in overweight and obesity care: Australian perspectives from a mixed methods study. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2024, 31, 2432285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.H.; Oliver, T.L.; Randolph, J.; Dowdell, E.B. Interventions for reducing weight bias in healthcare providers: An interprofessional systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Obes. 2022, 12, e12545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Murley, W.D.; Panda, S.; Stiver, C.A.; Garell, C.L.; Moin, T.; Crandall, A.K.; Tomiyama, A.J. Assessing weight stigma interventions: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2025, 14, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, M.I.; Hegel, M.T. Weight bias education for medical school faculty: Workshop and assessment. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 605–606.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayer, G.G.; Weiss, J.; Clearfield, M. Fundamentals for an osteopathic obesity designed study: The effects of education on osteopathic medical students’ attitudes regarding obesity. J. Osteopath. Med. 2017, 117, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barra, M.; Singh Hernandez, S.S. Too big to be seen: Weight-based discrimination among nursing students. Nurs. Forum. 2018, 53, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords or Keyword Combinations | Articles Identified in Initial Literature Search |

|---|---|

| Weight bias | 3027 |

| Weight bias OR weight stigma OR fatphobia OR anti-fat bias | 2389 |

| Weight stigma | 2086 |

| Weight stigma | 2077 |

| Anti-fat bias | 564 |

| Fat phobia | 291 |

| Weight stigma AND physical therapy | 39 |

| Weight stigma AND occupational therapy | 38 |

| Weight bias AND physical therapy | 30 |

| Weight bias AND occupational therapy | 27 |

| Anti-fat bias AND occupational therapy | 12 |

| Fatphobia AND occupational therapy | 10 |

| Anti-fat bias AND physical therapy | 9 |

| Fatphobia AND physical therapy | 7 |

| Author (Year) | Country | Study Design | Population | Selected Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setchell et al. (2014) [43] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | 256 physiotherapists (mean age 42 (11) y; female = 194) completed the AFA and provided free-text responses after the review of case studies | AFA Mean score 3.2 (1.1) Free-text responses to cases of overweight patients generated five themes: “negative language when speaking about weight in overweight patients”, “focus on weight management to the detriment of other important considerations”, “weight assumed to be individually controllable”, “directive or prescriptive responses rather than collaborative”, and “complexity of weight management not recognized” |

| Setchell et al. (2016) [55] | Australia | Discourse analysis (inductive qualitative design): data collected during 6 focus groups (4 to 6 participants per group) | 27 physiotherapists (mean age 39 (range 23–72); females = 18) | Four discourses developed from the focus group interviews:

|

| Elboim-Gabyzon et al. (2020) [45] | Israel | Cross-sectional survey | 285 physical therapists (mean age 39.6 (10.1) y; female = 223) 115 physical therapy students (mean age 26.4 (4.9); female = 68) | PT clinicians Fat Phobia Scale mean score = 3.6 (0.5) AFA mean score = 3.3 (1.2) BAOPs mean score = 16.4 (5.6) PT students Fat Phobia Scale mean score = 3.6 (0.4) AFA mean score = 3.0 (1.2) BAOPs mean score = 18 (5.7) Women (PT clinicians and students) had significantly higher AFA scores than men (p = 0.005; 0.039) Women (PT students) had significantly higher AFA fear of fat subscale score (p < 0.001) Women (PT clinicians) had significantly higher AFA fear of fat subscale score (p < 0.002) and lower BAOPs scores than male counterparts (p = 0.013) |

| Jones et al. (2021) [56] | Canada | Single-group pretest–posttest and an online cross-sectional survey | 27 physiotherapists participated in an 8 h interactive seminar (intervention) (mean age not provided; females = 22) 383 physiotherapists completed online surveys (mean age not provided; females = 321) | Seminar cohort ATOP Pre-seminar mean score = 71.3 (13.7) Post-seminar mean score = 63.5 (15.9) p < 0.001 BAOPs Pre-seminar mean score = 17.4 (6.4) Post-seminar mean score = 22.3 (7.6) p < 0.001 Both groups ATOP and BAOPs scores were statistically similar at baseline |

| O’Donoghue et al. (2021) [47] | Republic of Ireland | Cross-sectional survey | 179 final-year physiotherapy students (mean age 22.7 (2.8) y; female = 125) | ATOP Mean score 69.4 (14.3) 29% scored below 60 Causes of obesity N = 132 identified food addiction or psychological problems as “very important” or “extremely important” causes NEW Attitudes Scale Mean score = 20 (20.5) 24% had a negative attitude toward treating people with obesity PWBH 40% believed peers had negative attitudes towards patients with obesity 45% reported observing peers making jokes about patients who were obese |

| Friedman et al. (2022) [57] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | 5671 occupational therapy assistants and physical therapy assistants (mean age = 26.5 (8.8); female = 4403) completed the WIAT | WIAT Mean score = 0.50 (0.40) Majority of COTA/PTA “preferred thin people” (82.4%) Older individuals had higher anti-fat bias Females had lower anti-fat bias |

| Goff et al. (2024) [58] | Singapore | Cross-sectional | 525 healthcare providers (clinicians or students; mean age 31.58 (9.78) y) 57 occupational therapy professionals (clinicians = 26, students = 31) 129 physical therapy professionals (clinicians = 67, students = 62) | Scores provided for the entire sample of healthcare providers Fat Phobia Scale Mean score = 3.19 (0.20) Anti-fat Attitudes Questionnaire Mean score = 3.20 (1.25) |

| Rompolski et al. (2024) [59] | United States | Quasi-experimental pretest–posttest | Two US-based DPT cohorts (females = 71.6%) Cadaver (experimental) cohort participated in an anatomy dissection lab using donor bodies Control cohort participated in an anatomy lab using surface palpation, plastic models, and virtual anatomy | Cadaver cohort Baseline mean ATOP = 71.5 (16.0) Baseline mean M-WBIS = 2.7 (1.3) Control cohort Baseline mean ATOP = 77.2 (14.7) Baseline mean M-WBIS = 3.1 (1.3) No change in scores at the conclusion of the course |

| Webber et al. (2024) [60] | Canada | Cross-sectional survey | 184 physiotherapists (mean age not provided) and 34 physiotherapy students (mean age not provided) (females = 165) completed online surveys | Fat Attitudes Assessment Toolkit Positive attitudes toward people who are obese except on the following subscales: Attractiveness (72% had neutral or disagree scores) Responsibility (82% had neutral or disagree scores) Discrimination (38% had neutral or disagree scores) |

| Author (Year) | Country | Study Design | Population | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forhan and Law (2009) [61] | Canada | Nonexperimental pretest–posttest | 42 occupational therapists (mean age not provided; professional experience ranging from 0 to ≥15 years) Two cohorts (2006 n = 22; 2007 n = 20) participated in a workshop and completed ATOP and BAOPs measures | After completing the workshop: ATOP No change in attitudes (either cohort) BAOPs 2007 cohort had a significant change post workshop, reflecting improved beliefs |

| Leemhuis et al. (2010) [62] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | 145 members (mean age 42.35 (10.456) y; women = 137) of the American Occupational Therapy Association (OT = 125; COTA = 18; other = 1). | ATOP Mean score 68.6 (14.3) 20.7% scored below 60 Open-ended questions (Some) Barriers to treatment: negative attitudes, lack of facility resources, safety, and lack of education |

| Vroman and Cote (2011) [48] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | 189 occupational therapy students (mean age 24 years; females = 181; undergraduates n = 122) | AO-PESIS Obese clients received a significantly greater negative rating for the judgement and social distance scales compared to those who were of average weight ATOP Undergraduates = mean score 72.8 (15.4) Graduates = mean score 73.3 (13.9) 16% of all students scored below 60 BAOPs Undergraduates = mean score 19.5 (6.9) Graduates = mean score 20 (7.9) |

| Friedman et al. (2019) [63] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | 58 occupational therapy students (mean age 25.47 (5.09) years; women = 53) from 3 Midwestern universities completed the Weight Implicit Association Test | Weight Implicit Association Test Mean WIAT score = 0.33 (0.38) Majority “preferred thin people” (69%) |

| Lunt et al. (2022) [64] | Australia | Cross-sectional survey | 80 occupational therapists (0–21 years of experience) completed a novel survey (24 questions utilizing a 5-point Likert scale) | Knowledge of factors that cause obesity: 94% rated good to excellent Knowledge of weight management strategies: 56% good to excellent knowledge of OT role Conduct occupational assessments and interventions: 74% Assessments and interventions related to weight management: 23% Entry-level education related to working with patients of higher weight: 10% Top barriers to delivering care: lack of training, equipment (access and cost), environmental barriers, and weight bias |

| Friedman et al. (2022) [57] | United States | Cross-sectional survey | 5671 occupational therapy and physical therapy assistants (mean age = 26.5 (8.8); female = 4403) completed the WIAT | WIAT Mean score = 0.50 (0.40) Majority of COTA/PTA “preferred thin people” (82.4%) Older individuals had higher anti-fat bias Females had lower anti-fat bias |

| Goff et al. (2024) [58] | Singapore | Cross-sectional | 525 healthcare providers (clinicians or students; mean age 31.58 (9.78) y) 57 occupational therapy professionals (clinicians = 26, students = 31) 129 physical therapy professionals (clinicians = 67, students = 62) | Scores provided for the entire sample of healthcare providers Fat Phobia Scale Mean score = 3.19 (0.20) Anti-fat Attitudes Questionnaire Mean score = 3.20 (1.25) |

| Richards et al. (2024) [65] | Australia | Mixed methods Qualitative: reflexive thematic analysis Quantitative: 5-point Likert scale | 11 occupational therapists (mean age 39 y; female = 10) | Three themes associated with qualitative interviews: “exploring the client’s needs for weight management, incorporating weight management strategies in occupational therapy interventions, organization of current occupational therapy practice for people with obesity” OTs rated numerous interventions based on their effectiveness (1–5 scale) Examples include healthy eating advice = 3; physical activity advice = 4; client education = 2; and motivational training = 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brumitt, J.; Turner, K. Weight Stigma in Physical and Occupational Therapy: A Scoping Review. Obesities 2025, 5, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020046

Brumitt J, Turner K. Weight Stigma in Physical and Occupational Therapy: A Scoping Review. Obesities. 2025; 5(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrumitt, Jason, and Katherine Turner. 2025. "Weight Stigma in Physical and Occupational Therapy: A Scoping Review" Obesities 5, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020046

APA StyleBrumitt, J., & Turner, K. (2025). Weight Stigma in Physical and Occupational Therapy: A Scoping Review. Obesities, 5(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020046