Screening and Treating Disordered Eating in Weight Loss Surgery: A Rapid Review of Current Practices and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

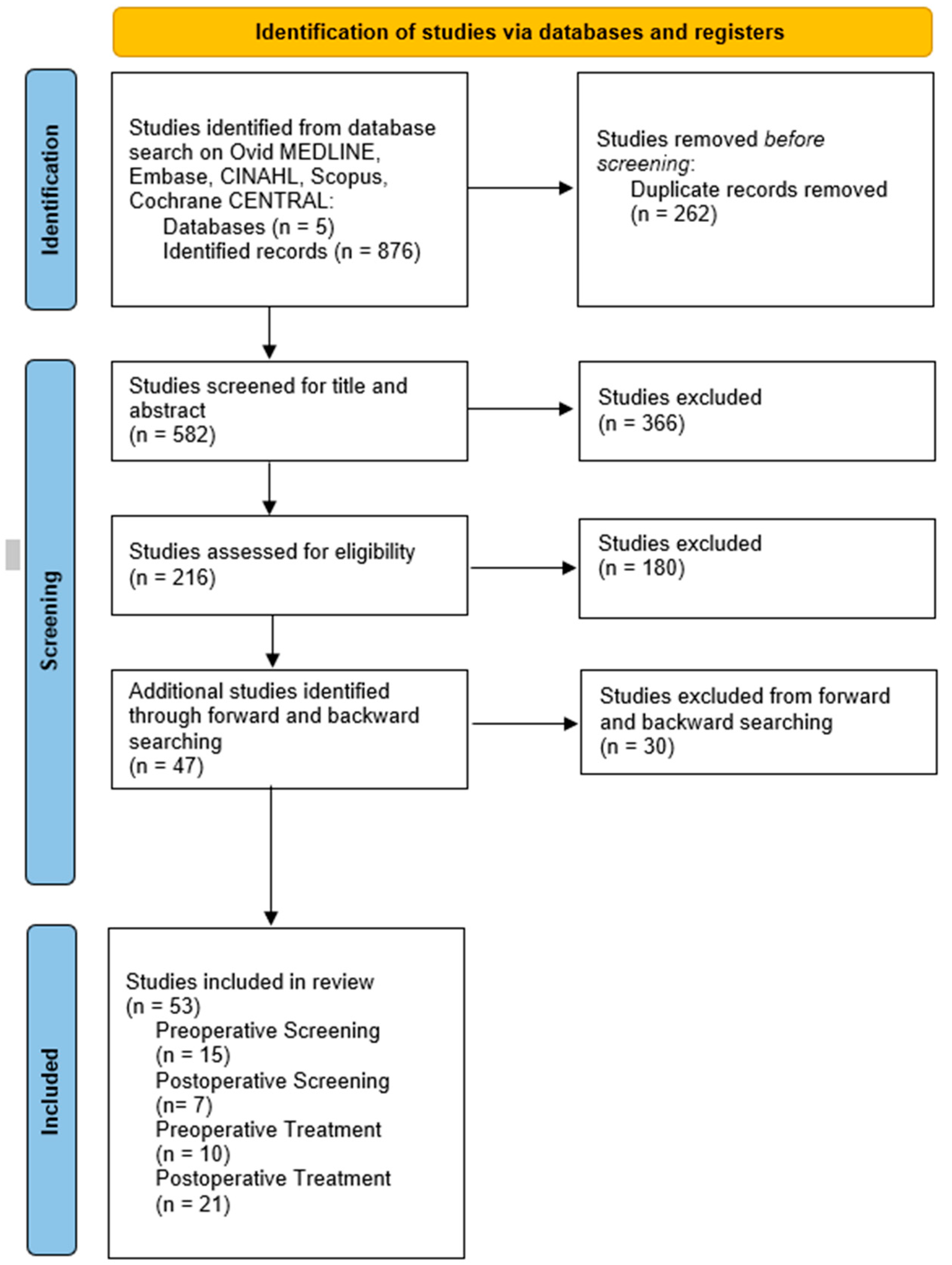

2. Methods

3. Findings

3.1. Current Evidence for Screening and Diagnosis

| Screening Measure | Studies | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-WLS Screening | ||

| Binge Eating Scale (BES) | Jeong et al., 2023 [23]; Marek et al., 2015 [24]; Grupski et al., 2013 [25]; Hood et al., 2013 [26] | The BES is reliable in identifying binge-eating symptoms in WLS-seeking patients. The BES has good internal consistency, concordance validity, and reliability in WLS patients pre-surgery. |

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 2—Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF) | Martin-Fernandez et al., 2021 [35]; Marek et al., 2014a [36]; Marek et al., 2014b [37]; Marek et al., 2013 [38] | Higher scores on demoralization, emotional dysfunction, antisocial, hypomanic, and impulsive subscales were associated with higher rates of disordered eating or BED diagnosis. |

| Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory 3 (MMPI-3) | Marek et al., 2024 [39]; Marek et al., 2021 [40] | Internalizing, externalizing, and somatic/cognitive dysfunction were associated with binge-eating and LOCE. An additional Eating Concerns Subscale was found to have good clinical utility in capturing eating psychopathology in WLS patients. |

| Eating Disorder Examination—Questionnaire (EDE-Q) | Parker et al., 2015 [41]; Grilo et al., 2013 [42] | The EDE-Q was found to be a poor fit to WLS patients; when the EDE-Q was modified, validity and reliability improved in both studies. |

| Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS) | Williams et al., 2017 [43] | The EDDS was found to have good clinical utility in identifying binge-eating behaviors in WLS patients. |

| Eating Expectancies Inventory (EEI) | Williams-Kerver et al., 2019 [44] | The EEI had good to excellent fit in its original factor structure. EEI scores were positively associated with EDDS symptom scores, BES scores, and binge-eating frequency. |

| Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) | Parker et al., 2015 [41] | A revised three-factor structure demonstrated good fit in identifying disordered eating in WLS patients pre-surgery. |

| Post-WLS Screening | ||

| Eating Disorder Examination—Bariatric Surgery Version (EDE-BSV) | Ivezaj et al., 2022 [21]; Wiedemann et al., 2020 [20]; de Zwaan et al., 2010 [19] | The EDE-BSV has high interrater reliability with the original EDE global and subscales, with excellent agreement for identifying LOCE episodes and associated disordered eating behaviors in WLS patients. |

| Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders—5th Edition (DSM-V) Clinical Assessment | Yu et al., 2023 [45]; Conceição et al., 2020 [46] | Due to dietary recommendations and anatomical changes post-surgery, DSM-V criteria for eating disorders, such as BED, are less applicable to WLS populations (e.g., “consuming large amounts of food when not physically hungry”). |

| Eating Loss of Control Scale (ELOCS) | Carr et al., 2019 [33] | A two-factor modified ELOCS was found to have good fit to a post-WLS sample. Correlations with the EDE-BSV suggested good construct validity in identifying disordered eating. |

| Eating Disorder After Bariatric Surgery—Questionnaire (EDABS-Q) | Globus et al., 2021 [29] | When compared to the EDE-BSV, the EDABS-Q significantly agreed with all items with high construct concordance. |

3.2. Current Evidence for Treatment

| Treatment Type | Studies | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-WLS Treatment | ||

| Individual Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Abiles et al., 2013 [48]; Gade et al., 2014 [62]; Gade et al., 2015 [63]; Cassin et al., 2016 [64]; Hjelmsæth et al., 2019 [65]; Paul et al., 2021 [49]; Paul et al., 2022 [50] | In general, CBT interventions were found to significantly improve binge-eating, eating disorder psychopathology, weight loss, and anxiety/mood symptoms post-intervention. Studies including follow-ups post-surgery found that these improvements were not maintained post-WLS. |

| Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Ashton et al., 2011 [66] | Group CBT had significant weight loss at 6- and 12-month follow-ups post-WLS; moreover, group CBT led to reductions in eating disorder symptomatology for those with and without BED, but the effect was not significant. |

| Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) | Delparte et al., 2019 [67] | DBT showed reductions in binge-eating, emotional eating, eating pathology, and clinical impairment as compared to treatment-as-usual at pre-surgery and at 6-month follow-ups. Weight was not reported. |

| Mindfulness-Based Intervention (MBI) | Felske et al., 2020 [68] | MBI showed improvements in eating behaviors and were maintained for 12 weeks; however, improvements deteriorated with time. Weight was not reported. |

| Post-WLS Treatment | ||

| Individual Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Sockalingam et al., 2017 [52] Sockalingam et al., 2019 [53] Rudolph & Hilbert, 2020 [56] Grilo et al., 2022 [69]; Sockalingam et al., 2022 [54] Smith et al., 2023 [70]; Sockalingam et al., 2023 [55] | In general, individual CBT was associated with significant improvements in disordered eating behaviors, eating-related psychopathology, anxiety/depression symptoms, and weight loss. In several cases, these improvements were found to be maintained for up to 1 year following the intervention. |

| Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | Lent et al., 2019 [71]; Himes et al., 2015 [57] | Group CBT had mixed findings. One study found no improvements in eating behaviors, weight, or mood as compared to controls. However, another study found significant reductions in eating behaviors and decreases in weight regain. Follow-up data were not recorded. |

| Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) | Gallé et al., 2017a [61]; Gallé et al., 2017b [72]; Himes et al., 2015 [57]; Hany et al., 2022 [60] | DBT has shown significant improvements in eating behaviors, emotional eating, weight, and psychiatric comorbidities post-intervention. These improvements were maintained for up to 1 year following the intervention. |

| Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBI) | Chacko et al., 2016 [73]; Wnuk et al., 2018 [74] | MBIs have shown significant improvements in eating behaviors, eating disorder psychopathology, and depressive symptoms; however, perceived stress has been found to increase post-intervention. One study found that improvements were maintained at a 4-month follow-up. Weight outcomes were not reported |

| Acceptance and Commitment Therapy or Acceptance-Based Therapy (ACT; ABT) | Weineland et al., 2012a [58] Weineland et al., 2012b [59] Bradley et al., 2017 [75] | ACT was found to significantly improve disordered eating behaviors, body dissatisfaction, quality of life, and weight acceptance; these improvements were maintained at a 6-month follow-up. Weight outcomes were not reported. |

| Schema Therapy | Sobhani et al., 2023 [76] | Those receiving schema therapy reported less maladaptive cognitive reasoning, more adaptive cognitive reasoning, and reductions in weight. This effect was maintained at a 6-month follow-up. Eating disorder behaviors were not reported. |

| Bariatric Surgery and Education (BaSE) Psychoeducational Group | Wild et al., 2015 [77] | There were no differences between the intervention and control groups in weight loss, health-related quality of life, or depression scores. Improvements were not maintained at a 1-year follow-up. Those with higher depression scores in the intervention showed slight improvements in quality of life and depressive symptoms. |

| Postbariatric Surgery (PBS) Protocol for Inpatient Eating Disorder Treatment | Schreyer et al., 2019 [78] | Preliminary findings suggest a positive association with the intervention, weight maintenance, and weight regain for those with restrictive eating disorders post-WLS. Eating disorder outcomes were not reported. Follow-up data were not reported. |

| Adapted Motivational Interviewing Intervention (AMI) | David et al., 2016 [79] | The intervention group showed significant improvements in binge-eating symptoms and dietary adherence across 12-week follow-ups as compared to the control group. AMI increased reported readiness, confidence, and self-efficacy in post-WLS guidelines. |

4. Future Directions for Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0096-01 Health Characteristics, Annual Estimates, Inactive. 2023. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009601 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Must, A.; Spadano, J.; Coakley, E.H.; Field, A.E.; Colditz, G.; Dietz, W.H. The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA 1999, 282, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimäki, M.; Strandberg, T.; Pentti, J.; Nyberg, S.T.; Frank, P.; Jokela, M.; Ervasti, J.; Suominen, S.B.; Vahtera, J.; Sipilä, P.N.; et al. Body-mass index and risk of obesity-related complex multimorbidity: An observational multicohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022, 10, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G.E.; Von Korff, M.; Saunders, K.; Miglioretti, D.L.; Crane, P.K.; van Belle, G.; Kessler, R.C. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwald, H.; Avidor, Y.; Braunwald, E.; Jensen, M.D.; Pories, W.; Fahrbach, K.; Schoelles, K. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004, 292, 1724–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Bariatric Surgery in Canada; CIHI: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Courcoulas, A.P.; King, W.C.; Belle, S.H.; Berk, P.; Flum, D.R.; Garcia, L.; Gourash, W.; Horlick, M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Pomp, A.; et al. Seven-Year Weight Trajectories and Health Outcomes in the Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) Study. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, L.; Lindroos, A.K.; Peltonen, M.; Torgerson, J.; Bouchard, C.; Carlsson, B.; Dahlgren, S.; Larsson, B.; Narbro, K.; Sjöström, C.D.; et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2683–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.G.; Moreira, L.; Carvalho, L.; Tianeze de Castro, C.; Vieira, R.A.L.; Guimarães, N.S. Weight regain after bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obes. Med. 2023, 45, 100528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, D.P.; Liu, L.; Arterburn, D.; Coleman, K.J.; Courcoulas, A.; Haneuse, S.; Johnson, E.; Li, R.A.; Theis, M.K.; Taylor, B.; et al. Remission and Relapse of Hypertension After Bariatric Surgery: A Retrospective Study on Long-Term Outcomes. Ann. Surg. Open 2022, 3, e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.M.; Lins, D.C.; Silva, L.B.; Araujo-Junior, J.G.C.; Zeve, J.L.M.; Ferraz, A.A.B. Metabolic surgery, weight regain and diabetes reemergence. Braz. Arch. Dig. Surg. 2013, 26 (Suppl. S1), 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meany, G.; Conceição, E.; Mitchell, J.E. Binge eating, binge eating disorder and loss of control eating: Effects on weight outcomes after bariatric surgery. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2014, 22, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezaj, V.; Carr, M.M.; Brode, C.; Devlin, M.; Heinberg, L.J.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Sysko, R.; Williams-Kerver, G.; Mitchell, J.E. Disordered eating following bariatric surgery: A review of measurement and conceptual considerations. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2021, 17, 1510–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Masheb, R.M.; Marcus, M.D.; Grilo, C.M. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery patients: A prospective, 24-month follow-up study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Orcutt, M.; Steffen, K.J.; Crosby, R.D.; Cao, L.; Garcia, L.; Mitchell, J.E. Loss of Control Eating and Binge Eating in the 7 Years Following Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Heinberg, L.J. A review of the psychosocial aspects of clinically severe obesity and bariatric surgery. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targowski, K.; Bank, S.; Carter, O.; Campbell, B.; Raykos, B. Break Free from ED; Centre for Clinical Interventions: Perth, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Z.; Fairburn, C. Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) [Database Record]; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zwaan, M.; Hilbert, A.; Swan-Kremeier, L.; Simonich, H.; Lancaster, K.; Howell, L.M.; Monson, T.; Crosby, R.D.; Mitchell, J.E. Comprehensive interview assessment of eating behavior 18-35 months after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2010, 6, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, A.A.; Ivezaj, V.; Lawson, J.L.; Lydecker, J.A.; Cooper, Z.; Grilo, C.M. Interrater reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination among postbariatric patients. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2020, 16, 1988–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezaj, V.; Kalarchian, M.A.; King, W.C.; Devlin, M.J.; Mitchell, J.E.; Crosby, R.D. Interrater reliability and internal consistency of the eating disorder examination in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2022, 18, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormally, J.; Black, S.; Daston, S.; Rardin, D. Binge Eating Scale (BES) [Database Record]; APA PsycTests: Washington, DC, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Hapenciuc, G.; Meza, E.; Le, J.T.; Heinberg, L.J.; Marek, R.J. Reevaluating the Binge Eating Scale cut-off using DSM-5 criteria: Analysis and replication in preoperative metabolic and bariatric surgery samples. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2023, 19, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, R.J.; Tarescavage, A.M.; Ben-Porath, Y.S.; Ashton, K.; Heinberg, L.J. Replication and evaluation of a proposed two-factor Binge Eating Scale (BES) structure in a sample of bariatric surgery candidates. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2015, 11, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupski, A.E.; Hood, M.M.; Hall, B.J.; Azarbad, L.; Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Corsica, J.A. Examining the Binge Eating Scale in screening for binge eating disorder in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, M.M.; Grupski, A.E.; Hall, B.J.; Ivan, I.; Corsica, J. Factor structure and predictive utility of the Binge Eating Scale in bariatric surgery candidates. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2013, 9, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, D.; Shikora, S.A.; Aarts, E.; Aminian, A.; Angrisani, L.; Cohen, R.V.; de Luca, M.; Faria, S.L.; Goodpaster, K.P.S.; Haddad, A.; et al. 2022 American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity and Metabolic Disorders (IFSO) Indications for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kops, N.L.; Vivan, M.A.; Fülber, E.R.; Fleuri, M.; Fagundes, J.; Friedman, R. Preoperative Binge Eating and Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Globus, I.; Kissileff, H.R.; Hamm, J.D.; Herzog, M.; Mitchell, J.E.; Latzer, Y. Comparison of Interview to Questionnaire for Assessment of Eating Disorders after Bariatric Surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, J.; Spirou, D.; Gascoigne, M.; Raman, J. Loss of control as a transdiagnostic feature in obesity-related eating behaviours: A systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2023, 31, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainik, U.; García-García, I.; Dagher, A. Uncontrolled eating: A unifying heritable trait linked with obesity, overeating, personality and the brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 50, 2430–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, K.K.; Roberto, C.A.; Barnes, R.D.; White, M.A.; Masheb, R.M.; Grilo, C.M. Development and validation of the eating loss of control scale. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.M.; Lawson, J.L.; Ivezaj, V.; Blomquist, K.K.; Grilo, C.M. Psychometric properties of the eating loss of control scale among postbariatric patients. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latner, J.D.; Mond, J.M.; Kelly, M.C.; Haynes, S.N.; Hay, P.J. The Loss of Control Over Eating Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, K.W.; Marek, R.J.; Heinberg, L.J.; Ben-Porath, Y.S. Six-year bariatric surgery outcomes: The predictive and incremental validity of presurgical psychological testing. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2021, 17, 1008–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, R.J.; Ben-Porath, Y.S.; Ashton, K.; Heinberg, L.J. Impact of using DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing binge eating disorder in bariatric surgery candidates: Change in prevalence rate, demographic characteristics, and scores on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–2 restructured form (MMPI-2-RF). Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek, R.J.; Ben-Porath, Y.S.; Ashton, K.; Heinberg, L.J. Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory-2 restructured form (MMPI-2-RF) scale score differences in bariatric surgery candidates diagnosed with binge eating disorder versus BMI-matched controls. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 47, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek, R.J.; Ben-Porath, Y.S.; Windover, A.; Tarescavage, A.M.; Merrell, J.; Ashton, K.; Lavery, M.; Heinberg, L.J. Assessing psychosocial functioning of bariatric surgery candidates with the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory-2 restructured form (MMPI-2-RF). Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 1864–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, R.J.; Ben-Porath, Y.S.; Heinberg, L.J. Six-year postoperative associations between the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory–3 (MMPI-3) and weight recurrence, eating behaviors, adherence, alcohol misuse, and quality of life. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2024, 20, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, R.J.; Martin-Fernandez, K.W.; Heinberg, L.J.; Ben-Porath, Y.S. An investigation of the eating concerns scale of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory -3 (MMPI-3) in a postoperative bariatric surgery sample. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 2335–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.; Mitchell, S.; O’Brien, P.; Brennan, L. Psychometric evaluation of disordered eating measures in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes. Surg. 2015, 26, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; Henderson, K.E.; Bell, R.L.; Crosby, R.D. Eating disorder examination-questionnaire factor structure and construct validity in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.A.; Hawkins, M.A.W.; Duncan, J.; Rummell, C.M.; Perkins, S.; Crowther, J.H. Maladaptive eating behavior assessment among bariatric surgery candidates: Evaluation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1183–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Kerver, G.A.; Schaefer, L.M.; Hawkins, M.A.W.; Crowther, J.H.; Duncan, J. Eating expectancies before bariatric surgery: Assessment and associations with weight loss trajectories. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yeh, K.-L.; Kalarchian, M.A.; Groth, S. Experiences of loss of control eating in women after bariatric surgery: A qualitative study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.M.; de Lourdes, M.; Peixoto, A.P.; Pinto-Bastos, A.; Goldschmidt, A.B.; Vaz, A.R. The utility of DSM-5 indicators of loss of control eating for the bariatric surgery population. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2020, 28, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A.K.R.; Herbozo, S.; Russell, A.; Eisele, H.; Zasadzinski, L.; Hassan, C.; Sanchez-Johnsen, L. Psychosocial interventions to reduce eating pathology in bariatric surgery patients: A systematic review. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 44, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abilés, V.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, S.; Abilés, J.; Obispo, A.; Gandara, N.; Luna, V.; Fernández-Santaella, M.C. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy in morbidity obese candidates for bariatric surgery with and without binge eating disorder. Nutr. Hosp. 2013, 28, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, L.; van der Heiden, C.; van Hoeken, D.; Deen, M.; Vlijm, A.; Klaassen, R.A.; Biter, L.U.; Hoek, H.W. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Versus Usual Care Before Bariatric Surgery: One-Year Follow-Up Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes. Surg. 2021, 31, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, L.; van der Heiden, C.; van Hoeken, D.; Deen, M.; Vlijm, A.; Klaassen, R.; Biter, L.U.; Hoek, H.W. Three- and five-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial on the effects of cognitive behavioral therapy before bariatric surgery. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 1824–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivezaj, V.; Kessler, E.E.; Lydecker, J.A.; Barnes, R.D.; White, M.A.; Grilo, C.M. Loss-of-control eating following sleeve gastrectomy surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2017, 13, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockalingam, S.; Cassin, S.E.; Wnuk, S.; Du, C.; Jackson, T.; Hawa, R.; Parikh, S.V. A Pilot Study on Telephone Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Patients Six-Months Post-Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockalingam, S.; Leung, S.E.; Hawa, R.; Wnuk, S.; Parikh, S.V.; Jackson, T.; Cassin, S.E. Telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy for female patients 1-year post-bariatric surgery: A pilot study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 13, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockalingam, S.; Leung, S.E.; Ma, C.; Hawa, R.; Wnuk, S.; Dash, S.; Jackson, T.; Cassin, S.E. The Impact of Telephone-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Mental Health Distress and Disordered Eating Among Bariatric Surgery Patients During COVID-19: Preliminary Results from a Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 1884–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockalingam, S.; Leung, S.E.; Ma, C.; Tomlinson, G.; Hawa, R.; Wnuk, S.; Jackson, T.; Urbach, D.; Okrainec, A.; Brown, J.; et al. Efficacy of telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy for weight loss, disordered eating, and psychological distress after bariatric surgery, a randomized clinical trial. Nutr. Obes. Exerc. 2023, 6, e2327099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, A.; Hilbert, A. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Postbariatric Surgery Patients with Mental Disorders: A Pilot Study. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himes, S.M.; Grothe, K.B.; Clark, M.M.; Swain, J.M.; Collazo-Clavell, M.L.; Sarr, M.G. Stop Regain: A Pilot Psychological Intervention for Bariatric Patients Experiencing Weight Regain. Obes. Surg. 2015, 25, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weineland, S.; Arvidsson, D.; Kakoulidis, T.P.; Dahl, J. Acceptance and commitment therapy for bariatric surgery patients, a pilot RCT. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 6, e1–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weineland, S.; Hayes, S.C.; Dahl, J. Psychological flexibility and the gains of acceptance-based treatment for post-bariatric surgery: Six-month follow-up and a test of the underlying model. Clin. Obes. 2012, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hany, M.; Elfiky, S.; Mansour, N.; Zidan, A.; Ibrahim, M.; Samir, M.; Allam, H.E.; Yassin, H.A.A.; Torensma, B. Dialectical behavioral therapy for emotional and mindless eating after bariatric surgery: A prospective exploratory cohort study. Obes. Surg. 2022, 32, 1570–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallé, F.; Cirella, A.; Salzano, A.M.; Di Onofrio, V.; Belfiore, P.; Liguori, G. Analyzing the effects of psychotherapy on weight loss after laparoscopic gastric bypass or laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in patients with borderline personality disorder: A prospective study. Scandanavian J. Surg. 2017, 106, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, H.; Hjelmesæth, J.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Friborg, O. Effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral therapy for dysfunctional eating among patients admitted for bariatric surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 127936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, H.; Friborg, O.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Småstuen, M.C.; Hjelmesæth, J. The Impact of a Preoperative Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) on Dysfunctional Eating Behaviours, Affective Symptoms and Body Weight 1 Year after Bariatric Surgery: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Obes. Surg. 2015, 25, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassin, S.E.; Sockalingam, S.; Du, C.; Wnuk, S.; Hawa, R.; Parikh, S.V. A pilot randomized controlled trial of telephone-based cognitive behavioural therapy for preoperative bariatric surgery patients. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 80, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelmesæth, J.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Gade, H.; Friborg, O. Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Eating Behaviors, Affective Symptoms, and Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, K.; Heinberg, L.J.; Windover, A.; Merrell, J. Positive response to binge eating intervention enhances postoperative weight loss. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2011, 7, 315–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delparte, C.A.; Power, H.A.; Gelinas, B.L.; Oliver, A.M.; Hart, R.D.; Wright, K.D. Examination of the effectiveness of a brief, adapted dialectical behavior therapy-skills training group for bariatric surgical candidates. Obes. Surg. 2019, 29, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felske, A.N.; Williamson, T.M.; Rash, J.A.; Telfer, J.A.; Toivonen, K.I.; Campbell, T. Proof of Concept for a Mindfulness-Informed Intervention for Eating Disorder Symptoms, Self-Efficacy, and Emotion Regulation among Bariatric Surgery Candidates. Behav. Med. 2020, 48, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; Ivezaj, V.; Duffy, A.J.; Gueorguieva, R. 24-Month follow-up of randomized controlled trial of guided-self-help for loss-of-control eating after bariatric surgery. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.E.; Dilip, A.; Ivezaj, V.; Duffy, A.J.; Grilo, C.M. Predictors of early weight loss in post-bariatric surgery patients receiving adjunctive behavioural treatments for loss-of-control eating. Clin. Obes. 2023, 13, e12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, M.R.; Campbell, L.K.; Kelly, M.C.; Lawson, J.L.; Murakami, J.M.; Gorrell, S.; Wood, G.C.; Yohn, M.M.; Ranck, S.; Petrick, A.T.; et al. The feasibility of a behavioral group intervention after weight-loss surgery: A randomized pilot trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallé, F.; Maida, P.; Assunta, C.; Giuliano, E.; Belfiore, P.; Liguori, G. Does post-operative psychotherapy contribute to improved comorbidities in bariatric patients with borderline personality disorder traints and bulimia tendencies? A prospective study. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 1872–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacko, S.A.; Yeh, G.Y.; Davis, R.B.; Wee, C.C. A mindfulness-based intervention to control weight after bariatric surgery: Preliminary results from a randomized controlled pilot trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 28, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wnuk, S.M.; Du, C.T.; Exan, J.V.; Wallwork, A.; Warwick, K.; Tremblay, L.; Kowgier, M.; Sockalingam, S. Mindfulness-based eating and awareness training for post-bariatric surgery patients: A feasibility pilot study. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 949–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, L.E.; Forman, E.M.; Kerrigan, S.G.; Goldstein, S.P.; Butryn, M.L.; Thomas, J.G.; Herbert, J.D.; Sarwer, D.B. Project HELP: A Remotely Delivered Behavioral Intervention for Weight Regain after Bariatric Surgery. Obes. Surg. 2017, 27, 586–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, Z.; Hosseini, S.V.; Honarparvaran, N.; Khazraei, H.; Amini, M.; Hedayati, A. The effectiveness of an online video-based group schema therapy in improvement of the cognitive emotion regulation strategies in women who have undergone bariatric surgery. BMC Surg. 2023, 23, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, B.; Hünnemeyer, K.; Sauer, H.; Hain, B.; Mack, I.; Schellberg, D.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; Weiner, R.; Meile, T.; Rudofsky, G.; et al. A 1-year videoconferencing-based psychoeducational group intervention following bariatric surgery: Results of a randomized controlled study. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bariatr. Surg. 2015, 11, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreyer, C.C.; Guarda, A.S.; Pletch, A.W.; Redgrave, G.W.; Salwen-Deremer, J.K.; Coughlin, J.W. A modified inpatient eating disorders treatment protocol for postbariatric surgery patients: Patient characteristics and treatment response. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 1612–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Sockalingam, S.; Wnuk, S.; Cassin, S.E. A pilot randomized controlled trial examining the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of Adapted Motivational Interviewing for post-operative bariatric surgery patients. Eat. Behav. 2016, 22, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Menezes, S.; Franco, A.J.; Marcolin, P.; Tomera, M. Role of GLP1-RA in Optimizing Weight Loss Post-Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Surg. 2024, 34, 3888–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, S.; McElroy, S.L.; Levangie, D.; Keshen, A. Use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in eating disorder populations. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2024, 57, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshen, A.; Kaplan, A.S.; Masson, P.; Ivanova, I.; Simon, B.; Ward, R.; Ali, S.I.; Carter, J.C. Binge eating disorder: Updated overview for primary care practitioners. Can. Fam. Physician Med. De Fam. Can. 2022, 68, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; Ivezaj, V.; Tek, C.; Yurkow, S.; Wiedemann, A.A.; Gueorguieva, R. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Lisdexamfetamine, Alone and Combined, for Binge-Eating Disorder With Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2024, 182, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, C.M.; Ivezaj, V.; Yurkow, S.; Tek, C.; Wiedemann, A.A.; Gueorguieva, R. Lisdexamfetamine maintenance treatment for binge-eating disorder following successful treatments: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 3334–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Price, C.; Fraser, K.; Bartel, S.; Vallis, M.; Jad, A.; Keshen, A. Screening and Treating Disordered Eating in Weight Loss Surgery: A Rapid Review of Current Practices and Future Directions. Obesities 2025, 5, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020019

Price C, Fraser K, Bartel S, Vallis M, Jad A, Keshen A. Screening and Treating Disordered Eating in Weight Loss Surgery: A Rapid Review of Current Practices and Future Directions. Obesities. 2025; 5(2):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020019

Chicago/Turabian StylePrice, Colby, Kaela Fraser, Sara Bartel, Michael Vallis, Ahmed Jad, and Aaron Keshen. 2025. "Screening and Treating Disordered Eating in Weight Loss Surgery: A Rapid Review of Current Practices and Future Directions" Obesities 5, no. 2: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020019

APA StylePrice, C., Fraser, K., Bartel, S., Vallis, M., Jad, A., & Keshen, A. (2025). Screening and Treating Disordered Eating in Weight Loss Surgery: A Rapid Review of Current Practices and Future Directions. Obesities, 5(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/obesities5020019