Effect of Inhalation of Hydrogen Gas on Postoperative Recovery After Hepatectomy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Oversight

2.2. Participants

2.3. Randomization and Masking

2.4. Interventions

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Sample Size and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Perioperative Course

3.3. Early Postoperative Outcomes (Postoperative Day 3)

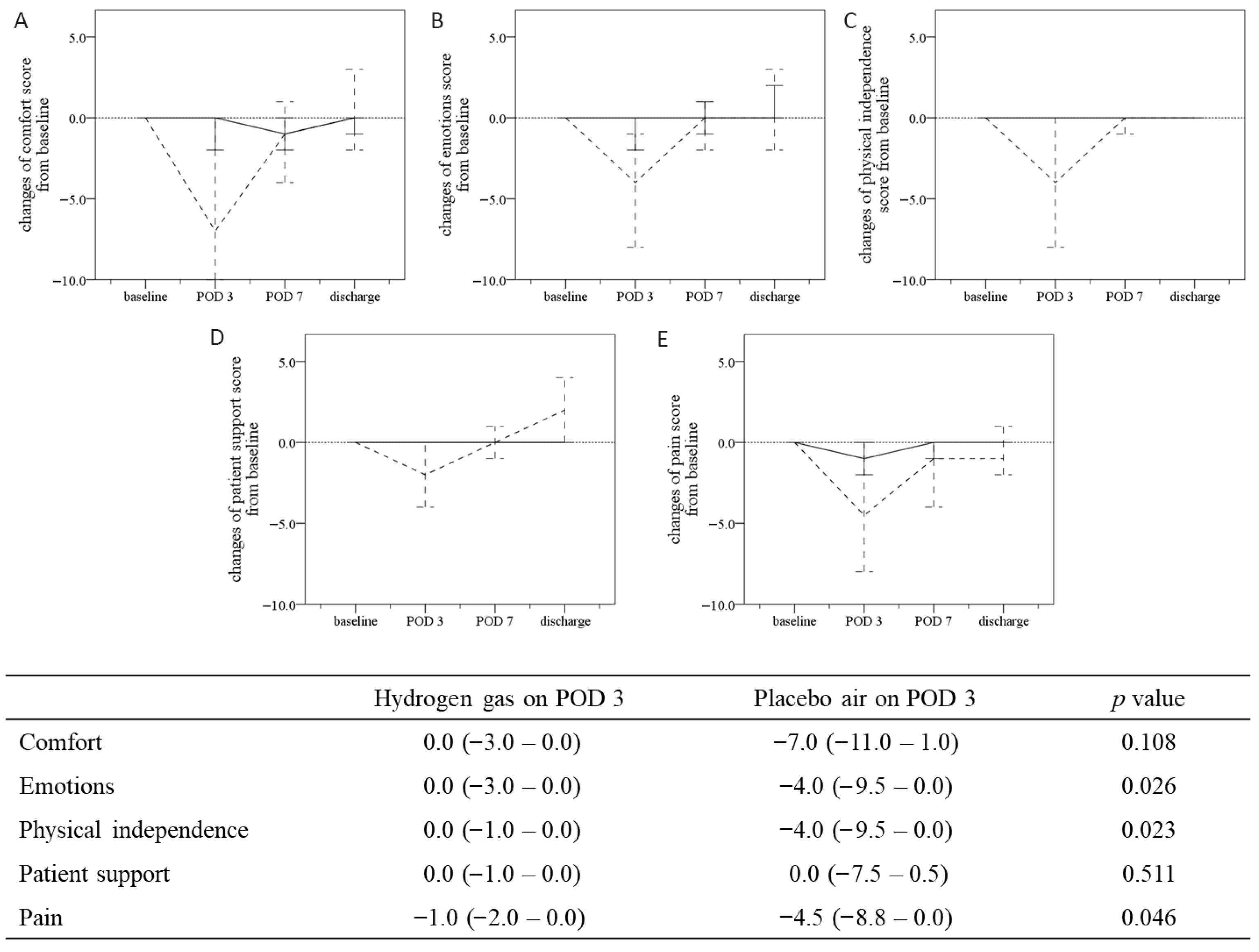

3.4. QoR-40 at Postoperative Day 3 and Subsequent Time Course

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peralta, C.; Jiménez-Castro, M.B.; Gracia-Sancho, J. Hepatic ischemia–reperfusion injury: Pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Petrowsky, H.; Hong, J.C.; Busuttil, R.W.; Kupiec-Weglinski, J.W. Ischaemia–reperfusion injury in liver transplantation—From bench to bedside. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serracino-Inglott, F.; Habib, N.A.; Mathie, R.T. Hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Surg. 2001, 181, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsawa, I.; Ishikawa, M.; Takahashi, K.; Watanabe, M.; Nishimaki, K.; Yamagata, K.; Katsura, K.-I.; Katayama, Y.; Asoh, S.; Ohta, S. Hydrogen acts as a therapeutic antioxidant by selectively reducing cytotoxic oxygen radicals. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, K.; Sano, M.; Ohsawa, I.; Shinmura, K.; Tamaki, K.; Kimura, K.; Endo, J.; Katayama, T.; Kawamura, A.; Kohsaka, S.; et al. Inhalation of hydrogen gas reduces infarct size in the rat model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 373, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, K.; Cho, S.; Shibata, I.; Yoshitomi, O.; Maekawa, T.; Sumikawa, K. Inhalation of hydrogen gas protects against myocardial stunning and infarction in swine. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2012, 46, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Suzuki, M.; Hayashida, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yoshizawa, J.; Shibusawa, T.; Sano, M.; Hori, S.; Sasaki, J. Hydrogen gas inhalation alleviates oxidative stress in patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2020, 67, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Hayashida, K.; Sano, M.; Suzuki, M.; Shibusawa, T.; Yoshizawa, J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Ohta, S.; Morisaki, H.; et al. Feasibility and safety of hydrogen gas inhalation for patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome: A first-in-human pilot study. Circ. J. 2016, 80, 1870–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, R.T.; Fan, S.T.; Yu, W.C.; Lam, B.K.; Chan, F.Y.; Wong, J. A prospective longitudinal study of quality of life after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Arch. Surg. 2001, 136, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.C.; Eid, S.; Scoggins, C.R.; McMasters, K.M. Health-related quality of life: Return to baseline after major and minor liver resection. Surgery 2007, 142, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banz, V.M.; Inderbitzin, D.; Fankhauser, R.; Studer, P.; Candinas, D. Long-term quality of life after hepatic resection: Health is not simply the absence of disease. World J. Surg. 2009, 33, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Bruns, H.; Krätschmer, K.; Hinz, U.; Brechtel, A.; Keller, M.; Büchler, M.W.; Schemmer, P. Quality of life after curative liver resection: A single-center analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2388–2395. [Google Scholar]

- Myles, P.S.; Weitkamp, B.; Jones, K.; Melick, J.; Hensen, S. Validity and reliability of a postoperative quality of recovery score: The QoR-40. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000, 84, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornall, B.F.; Myles, P.S.; Smith, C.L.; Burke, J.A.; Leslie, K.; Pereira, M.J.; Bost, J.E.; Kluivers, K.B.; Nilsson, U.G.; Tanaka, Y.; et al. Measurement of quality of recovery using the QoR-40: A quantitative systematic review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2013, 111, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myles, P.S.; Myles, D.B.; Galagher, W.; Chew, C.; Macdonald, N.; Dennis, A. Minimal clinically important difference for three quality of recovery scales. Anesthesiology 2016, 125, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, A.; Takahashi, S.; Goto, T. Effect of preoperative oral carbohydrate or oral rehydration solution on postoperative quality of recovery: A randomized controlled trial using QoR-40. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaibori, M.; Kosaka, H. Effect of hydrogen gas inhalation on patient QOL after hepatectomy: Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, S. Recent progress toward hydrogen medicine: Potential of molecular hydrogen for preventive and therapeutic applications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 2241–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Yang, M.; Yang, N.N.; Yin, X.X.; Song, W.G. Molecular hydrogen: A preventive and therapeutic medical gas for various diseases. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 102653–102673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, H.; Gould, R.L.; Abrol, E.; Howard, R. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between peripheral inflammatory cytokines and generalised anxiety disorder. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.G.; Cheon, E.J.; Bai, D.S.; Lee, Y.H.; Koo, B.H. Stress and heart rate variability: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graille, M.; Wild, P.; Sauvain, J.-J.; Hemmendinger, M.; Guseva Canu, I.; Hopf, N.B. Urinary 8-OHdG as a Biomarker for Oxidative Stress: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, M.; Kobashi, G.; Umesawa, M.; Cui, R.; Yamagishi, K.; Imano, H.; Okada, T.; Kiyama, M.; Kitamura, A.; Sairenchi, T.; et al. Urinary 8-Hydroxy-2′-Deoxyguanosine Levels and Cardiovascular Disease Incidence in Japan. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2020, 27, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dang, P.; Xue, H.; Li, T.; Zhou, M.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y. Alpha-Lipoic Acid Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Brain Damage in Patients with Sevoflurane Anesthesia. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1572156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | n (%) or Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Gas n = 31 | Placebo Air n = 33 | |

| Age | 74.0 (67.0–79.0) | 71.0 (61.0–77.0) |

| Gender, male | 17 (54.8) | 21 (63.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.6 (19.9–25.3) | 23.6 (21.4–26.7) |

| Smoking status, yes | 5 (16.1) | 6 (18.2) |

| Alcohol consumption, none/occasional/habitual | 24/1/6 (77.4/3.2/19.4) | 25/4/4 (75.8/12.1/12.1) |

| Diagnosis: HCC/CRLM/ICC/Others | 16/7/5/3 (51.6/22.6/16.1/9.7) | 17/8/4/4 (51.5/12.1/24.2/12.1) |

| WBC counts (×102/µL) | 50.0 (42.0–62.0) | 52.0 (46.5–67.0) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.7 (11.9–14.2) | 13.1 (11.4–14.0) |

| Platelet count (×104/µL) | 18.1 (16.0–21.4) | 19.0 (15.1–21.6) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.2 (3.8–4.4) | 4.2 (3.7–4.6) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| AST, U/L | 26.0 (20.0–33.0) | 24.0 (20.0–37.0) |

| ALT, U/L | 22.0 (14.0–35.0) | 19.0 (14.0–40.5) |

| ALP, U/L | 84.0 (66.0–96.0) | 79.0 (69.0–108.5) |

| GGT, U/L | 35.0 (16.0–72.0) | 48.0 (31.5–86.0) |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.11 (0.03–0.34) | 0.08 (0.05–0.22) |

| PT activity, % | 102.7 (95.2–112.1) | 100.6 (89.3–107.5) |

| ALBI index | −2.87 (−3.07–−2.53) | −2.99 (−3.22–−2.42) |

| Surgical approach: laparoscopic/open | 23/8 (74.2/25.8) | 23/10 (69.7/30.3) |

| Liver resection extent: ≥section/≤segment | 12/19 (38.7/61.3) | 15/18 (45.5/54.5) |

| Diagnosis: HCC/non-HCC | 16/15 (51.6/48.4) | 17/16 (51.5/48.5) |

| Parameters | n (%) or Median (IQR) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Gas n = 31 | Placebo Air n = 33 | ||

| Operative time, min | 311.0 (240.0–374.0) | 325.0 (256.0–362.0) | 0.712 |

| Blood loss, mL | 357.0 (56.0–598.0) | 326.0 (107.0–658.0) | 0.920 |

| Pringle maneuver time, min | 60.0 (0.0–86.0) | 61.0 (30.5–88.5) | 0.716 |

| Clavien-Dindo score, IIIa and more | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.1) | 0.704 |

| Postoperative hospital stay, days | 13.0 (11.0–20.0) | 13.0 (11.0–17.0) | 0.746 |

| Parameters | n (%) or Median (IQR) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Gas n = 31 | Placebo Air n = 33 | ||

| Body temperature, °C | 36.8 (36.5–36.9) | 36.8 (36.6–37.2) | 0.418 |

| Maximum NRS, 0–10 | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.151 |

| Food intake, % | 70.0 (50.0–100.0) | 70.0 (40.0–80.0) | 0.349 |

| Steps per day | 243.0 (42.0–1307.0) | 87.5 (30.3–806.0) | 0.165 |

| Urine volume, L | 2.7 (1.7–3.2) | 2.9 (1.9–3.1) | 0.788 |

| Body weight, kg | 63.6 (55.2–72.6) | 66.7 (53.7–77.2) | 0.724 |

| WBC counts (×102/µL) | 74.0 (66.0–86.0) | 86.0 (67.0–100.0) | 0.136 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.1 (9.1–12.7) | 10.9 (10.0–11.6) | 0.856 |

| Platelet count (×104/µL) | 12.2 (9.8–14.8) | 12.1 (8.6–14.9) | 0.573 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9 (2.6–3.2) | 3.0 (2.5–3.3) | 0.962 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.200 |

| AST, U/L | 146.0 (97.0–187.0) | 150.0 (93.5–280.5) | 0.472 |

| ALT, U/L | 238.0 (161.0–329.0) | 262.0 (160.5–503.5) | 0.307 |

| ALP, U/L | 74.0 (56.0–85.0) | 82.0 (51.5–109.0) | 0.279 |

| GGT, U/L | 35.0 (22.0–63.0) | 51.0 (27.0–83.0) | 0.110 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 7.4 (4.1–14.9) | 8.8 (4.7–11.8) | 0.930 |

| PT activity, % | 85.0 (77.7–95.3) | 76.2 (67.8–86.1) | 0.005 |

| ALBI index | −1.71 (−1.97–−1.51) | −1.79 (−1.98–−1.41) | 0.788 |

| QoR-40 score | 192.0 (184.0–198.0) | 163.0 (140.0–190.0) | <0.001 |

| ΔQoR-40 score | −2.0 (−9.0–0.0) | −19.0 (−41.0–−0.5) | 0.022 |

| Urinary 8-OHdG | 7.6 (5.1–10.4) | 5.7 (3.7–9.0) | 0.382 |

| Δ Urinary 8-OHdG | −0.5 (−2.6–1.6) | −2.3 (−4.4–1.8) | 0.322 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kosaka, H.; Nguyen, K.V.; Matsui, K.; Matsushima, H.; Miyauchi, T.; Kiguchi, G.; Yamamoto, H.; Lai, T.T.; Duong, H.H.; Mori, K.; et al. Effect of Inhalation of Hydrogen Gas on Postoperative Recovery After Hepatectomy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Hydrogen 2025, 6, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040124

Kosaka H, Nguyen KV, Matsui K, Matsushima H, Miyauchi T, Kiguchi G, Yamamoto H, Lai TT, Duong HH, Mori K, et al. Effect of Inhalation of Hydrogen Gas on Postoperative Recovery After Hepatectomy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Hydrogen. 2025; 6(4):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040124

Chicago/Turabian StyleKosaka, Hisashi, Khanh Van Nguyen, Kosuke Matsui, Hideyuki Matsushima, Takumi Miyauchi, Gozo Kiguchi, Hidekazu Yamamoto, Tung Thanh Lai, Hoang Hai Duong, Keita Mori, and et al. 2025. "Effect of Inhalation of Hydrogen Gas on Postoperative Recovery After Hepatectomy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial" Hydrogen 6, no. 4: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040124

APA StyleKosaka, H., Nguyen, K. V., Matsui, K., Matsushima, H., Miyauchi, T., Kiguchi, G., Yamamoto, H., Lai, T. T., Duong, H. H., Mori, K., Ishikawa, H., & Kaibori, M. (2025). Effect of Inhalation of Hydrogen Gas on Postoperative Recovery After Hepatectomy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Hydrogen, 6(4), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/hydrogen6040124