Dimethylglycine as a Potent Modulator of Catalase Stability and Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Stock Solutions

2.2. Protein Aggregation Studies for Catalase

2.3. Measurement of Catalase Activity

2.4. Calculation of Specific Activity

2.5. Thermal Denaturation Studies

2.6. Circular Dichroism (CD) Measurements

2.7. Fluorescence Spectral Measurements

2.8. Light Scattering Assay

2.9. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.10. Fluorescence Microscopy

2.11. Statistical Analysis

2.12. Molecular Docking

2.13. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

3. Results

3.1. Screening of Metabolites Having Inhibitory Effect on Catalase Aggregation

3.2. DMG Reduces the Amyloid Character of Catalase Aggregates

3.3. DMG Enhances Catalase-Mediated Decomposition of Hydrogen Peroxide

3.4. DMG Increases Tm of Catalase

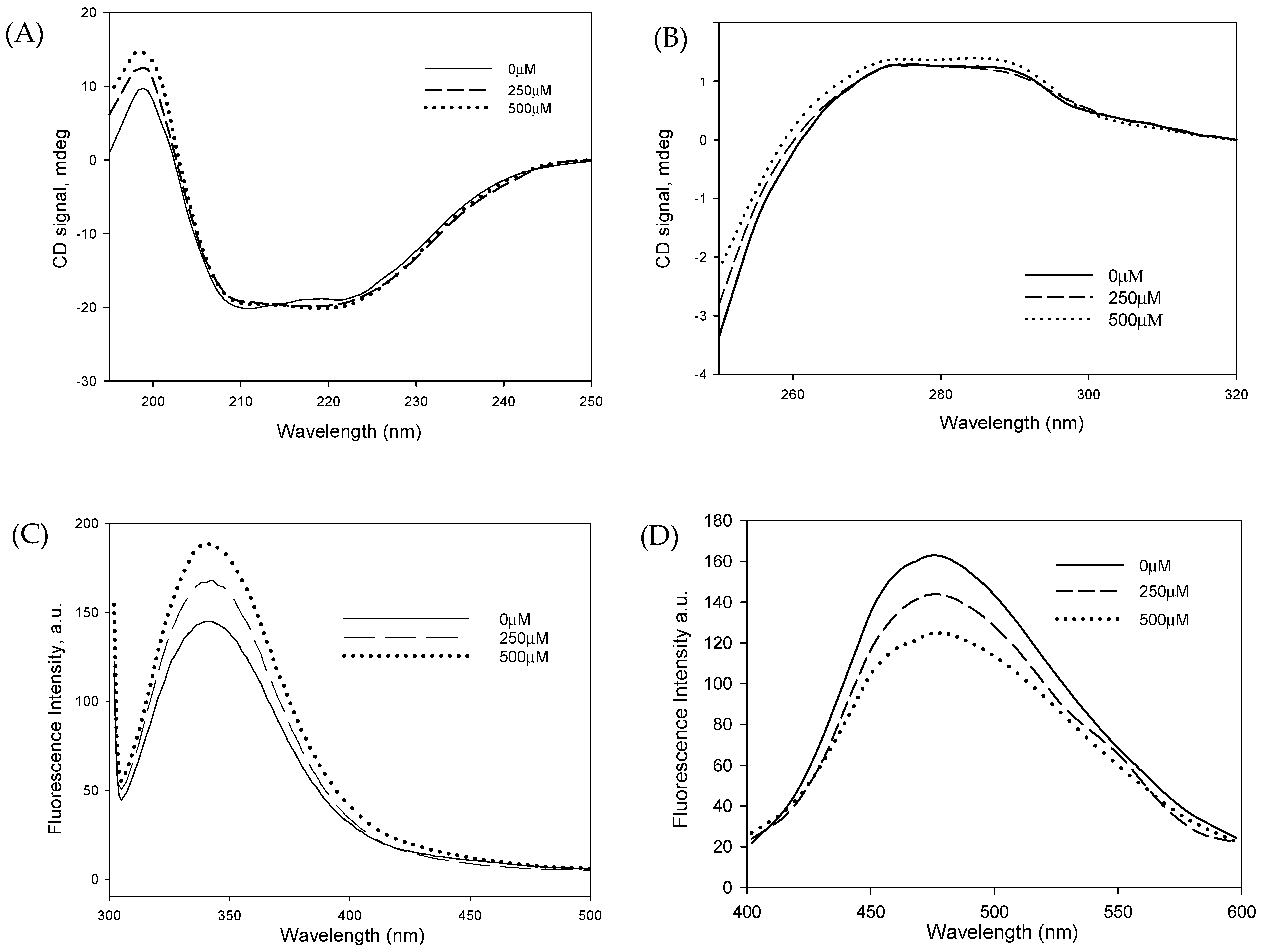

3.5. DMG Induces Significant Structural Alterations in Catalase

3.6. DMG Binds to an Allosteric Site of Catalase and May Contribute to Enhanced Activity and Stability

3.7. MD Simulations Highlight DMG-Induced Conformational Shifts

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Zhou, Q.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring the Landscape of Cognitive Decline. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 3800–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamatham, P.T.; Shukla, R.; Khatri, D.K.; Vora, L.K. Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease: Breaking the Memory Barrier. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment—PMC. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7764106/ (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Lanctôt, K.L.; Hahn-Pedersen, J.H.; Eichinger, C.S.; Freeman, C.; Clark, A.; Tarazona, L.R.S.; Cummings, J. Burden of Illness in People with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Epidemiology, Comorbidities and Mortality. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 11, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Tan, C.-C.; Xu, W.; Hu, H.; Cao, X.-P.; Dong, Q.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.-T. The Prevalence of Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 73, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocahan, S.; Doğan, Z. Mechanisms of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis and Prevention: The Brain, Neural Pathology, N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptors, Tau Protein and Other Risk Factors. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2017, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampel, H.; Hardy, J.; Blennow, K.; Chen, C.; Perry, G.; Kim, S.H.; Villemagne, V.L.; Aisen, P.; Vendruscolo, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; et al. The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 5481–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimon, M.; Takeda, S.; Post, K.L.; Svirsky, S.; Hyman, B.T.; Berezovska, O. Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation Are Upstream of Amyloid Pathology. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 84, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, P.; Sun, Z.; Gou, F.; Wang, J.; Fan, Q.; Zhao, D.; Yang, L. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Impairment: Key Drivers in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 104, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, N.; Khan, R.H. Protein Aggregation: Consequences, Mechanism, Characterization and Inhibitory Strategies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 125123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Wang, X.; Nunomura, A.; Moreira, P.I.; Lee, H.; Perry, G.; Smith, M.A.; Zhu, X. Oxidative Stress Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2008, 5, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danial, J.S.H.; Klenerman, D. Single Molecule Imaging of Protein Aggregation in Dementia: Methods, Insights and Prospects. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 153, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurutas, E.B. The Importance of Antioxidants Which Play the Role in Cellular Response against Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress: Current State. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snezhkina, A.V.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Kardymon, O.L.; Savvateeva, M.V.; Melnikova, N.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Dmitriev, A.A. ROS Generation and Antioxidant Defense Systems in Normal and Malignant Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 6175804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodičková, A.; Koren, S.A.; Wojtovich, A.P. Site-Specific Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegeneration. Mitochondrion 2022, 64, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irato, P.; Santovito, G. Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Molecules with Antioxidant Function. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimse, S.B.; Pal, D. Free Radicals, Natural Antioxidants, and Their Reaction Mechanisms. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27986–28006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.-J.; Won, Y.-S.; Kim, E.-K.; Park, S.-I.; Lee, S.J. Free Radicals and Their Impact on Health and Antioxidant Defenses: A Review. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, Z. Therapeutic Potentials of Catalase: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Health Sci. 2024, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gebicka, L.; Krych-Madej, J. The Role of Catalases in the Prevention/Promotion of Oxidative Stress. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 197, 110699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Alrumaihi, F.; Sarwar, T.; Babiker, A.Y.; Khan, A.A.; Prabhu, S.V.; Rahmani, A.H. Exploring Therapeutic Potential of Catalase: Strategies in Disease Prevention and Management. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransy, C.; Vaz, C.; Lombès, A.; Bouillaud, F. Use of H2O2 to Cause Oxidative Stress, the Catalase Issue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.V.; Javadov, S.; Sommer, N. Cellular ROS and Antioxidants: Physiological and Pathological Role. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasso, M.; Gambino, S.; Romanelli, M.G.; Donadelli, M.; Scupoli, M.T. Browsing the Oldest Antioxidant Enzyme: Catalase and Its Multiple Regulation in Cancer. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 172, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abrash, A.S.; Al-Quobaili, F.A.; Al-Akhras, G.N. Catalase Evaluation in Different Human Diseases Associated with Oxidative Stress. Saudi Med. J. 2000, 21, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Perry, G.; Lee, H.; Zhu, X. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Younus, H.; Khan, M.A. Catalase Functions and Glycation: Their Central Roles in Oxidative Stress, Metabolic Disorders, and Neurodegeneration. Catalysts 2025, 15, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, L.K.; Lee, M.T.C.; Yang, J. Inhibitors of Catalase-Amyloid Interactions Protect Cells from β-Amyloid-Induced Oxidative Stress and Toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 38933–38943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, F.G.; Pahan, K.; Khan, M.; Barbosa, E.; Singh, I. Abnormality in Catalase Import into Peroxisomes Leads to Severe Neurological Disorder. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 2961–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabbani, G.; Choi, I. Roles of Osmolytes in Protein Folding and Aggregation in Cells and Their Biotechnological Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, S.M.; Zehra, A.; Khan, R.H. Biophysical Insight into Protein Folding, Aggregate Formation and Its Inhibition Strategies. Protein Pept. Lett. 2022, 29, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, T.I.; Zaman, M.; Khan, M.V.; Ali, M.; Rabbani, G.; Ishtikhar, M.; Khan, R.H. A Mechanistic Insight into Protein-Ligand Interaction, Folding, Misfolding, Aggregation and Inhibition of Protein Aggregates: An Overview. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 106, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahban, M.; Zolghadri, S.; Salehi, N.; Ahmad, F.; Haertlé, T.; Rezaei-Ghaleh, N.; Sawyer, L.; Saboury, A.A. Thermal Stability Enhancement: Fundamental Concepts of Protein Engineering Strategies to Manipulate the Flexible Structure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 214, 642–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Chu, P.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Cao, Z.; Xu, M.; Ren, Q.; Xie, X. Dual-Scale Porous/Grooved Microstructures Prepared by Nanosecond Laser Surface Texturing for High-Performance Vapor Chambers. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 73, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Huang, J.; Song, M.; Hu, Y. Thermal Performance of a Thin Flat Heat Pipe with Grooved Porous Structure. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 173, 115215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, L.; Khurana, R.; Coats, A.; Frokjaer, S.; Brange, J.; Vyas, S.; Uversky, V.N.; Fink, A.L. Effect of Environmental Factors on the Kinetics of Insulin Fibril Formation: Elucidation of the Molecular Mechanism. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 6036–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, S.; Singh, L.R. Macromolecular Crowding Decelerates Aggregation of a β-Rich Protein, Bovine Carbonic Anhydrase: A Case Study. J. Biochem. 2014, 156, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwan, M.H. Simple Spectrophotometric Assay for Measuring Catalase Activity in Biological Tissues. BMC Biochem. 2018, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.C.; Fraaije, J.G.E.M. LINCS: A Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle Mesh Ewald: An W Log(N) Method for Ewald Sums in Large Systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vivo, M.; Masetti, M.; Bottegoni, G.; Cavalli, A. Role of Molecular Dynamics and Related Methods in Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4035–4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Karmalawy, A.A.; Dahab, M.A.; Metwaly, A.M.; Elhady, S.S.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Eissa, I.H.; Darwish, K.M. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation Revealed the Potential Inhibitory Activity of ACEIs Against SARS-CoV-2 Targeting the hACE2 Receptor. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 661230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnittali, M.; Rissanou, A.N.; Harmandaris, V. Structure Of Biomolecules Through Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 156, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, Y.; Igarashi, R.; Ushiku, Y.; Mitsutake, A. Analysis of Protein Folding Simulation with Moving Root Mean Square Deviation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H. Targeting Oxidative Stress in Disease: Promise and Limitations of Antioxidant Therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Deng, F.; Deng, Z. Oxidative Stress: Signaling Pathways, Biological Functions, and Disease. MedComm 2025, 6, e70268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warepam, M.; Mishra, A.K.; Sharma, G.S.; Kumari, K.; Krishna, S.; Khan, M.S.A.; Rahman, H.; Singh, L.R. Brain Metabolite, N-Acetylaspartate Is a Potent Protein Aggregation Inhibitor. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 617308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, N.G. Amyloid-Beta Binds Catalase with High Affinity and Inhibits Hydrogen Peroxide Breakdown. Biochem. J. 1999, 344, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, H.N.; Rolfo, M.; Ferraris, A.M.; Gaetani, G.F. Mechanisms of Protection of Catalase by NADPH. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 13908–13914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, C.D.; Arvai, A.S.; Bourne, Y.; Tainer, J.A. Active and Inhibited Human Catalase Structures: Ligand and NADPH Binding and Catalytic Mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 2000, 296, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugadev, R.; Ponnuswamy, M.N.; Sekar, K. Structural Analysis of NADPH Depleted Bovine Liver Catalase and Its Inhibitor Complexes. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 2, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- LeVine, H.; Walker, L.C. What Amyloid Ligands Can Tell Us about Molecular Polymorphism and Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 42, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Xia, W.; Zhao, Q.; Xiang, H.; Han, C.; Zhang, S.; Gu, W.; Tang, W.; Li, Y.; Tan, L.; et al. Structural Mechanism for Specific Binding of Chemical Compounds to Amyloid Fibrils. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, T.S.; Mackey, M.; Hunter, C.A. Discovery of High-Affinity Amyloid Ligands Using a Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Pipeline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15936–15950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulawa, C.E.; Connelly, S.; Devit, M.; Wang, L.; Weigel, C.; Fleming, J.A.; Packman, J.; Powers, E.T.; Wiseman, R.L.; Foss, T.R.; et al. Tafamidis, a Potent and Selective Transthyretin Kinetic Stabilizer That Inhibits the Amyloid Cascade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9629–9634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, T.; Merlini, G.; Bulawa, C.E.; Fleming, J.A.; Judge, D.P.; Kelly, J.W.; Maurer, M.S.; Planté-Bordeneuve, V.; Labaudinière, R.; Mundayat, R.; et al. Mechanism of Action and Clinical Application of Tafamidis in Hereditary Transthyretin Amyloidosis. Neurol. Ther. 2016, 5, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, E.C.; Ebert, B.L. The Novel Mechanism of Lenalidomide Activity. Blood 2015, 126, 2366–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miñarro-Lleonar, M.; Bertran-Mostazo, A.; Duro, J.; Barril, X.; Juárez-Jiménez, J. Lenalidomide Stabilizes Protein-Protein Complexes by Turning Labile Intermolecular H-Bonds into Robust Interactions. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 6037–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonso-Prieto, M.; Biarnés, X.; Vidossich, P.; Rovira, C. The Molecular Mechanism of the Catalase Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11751–11761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zenin, V.; Ivanova, J.; Pugovkina, N.; Shatrova, A.; Aksenov, N.; Tyuryaeva, I.; Kirpichnikova, K.; Kuneev, I.; Zhuravlev, A.; Osyaeva, E.; et al. Resistance to H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Cells of Different Phenotypes. Redox Biol. 2022, 50, 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Wehner, D.; Prabhu, G.R.D.; Moon, E.; Safferthal, M.; Bechtella, L.; Österlund, N.; Vos, G.M.; Pagel, K. Elucidating Reactive Sugar-Intermediates by Mass Spectrometry. Commun. Chem. 2025, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Gupta, A.; Chigurupati, S.; Singh, S.; Sehgal, A.; Badavath, V.N.; Alhowail, A.; Mani, V.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; et al. Natural and Synthetic Agents Targeting Reactive Carbonyl Species against Metabolic Syndrome. Molecules 2022, 27, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amidfar, M.; Askari, G.; Kim, Y.-K. Association of Metabolic Dysfunction with Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Metabolomic Evidence. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 128, 110848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tan, L. Association between Alzheimer’s Disease and Metabolic Syndrome: Unveiling the Role of Dyslipidemia Mechanisms. Brain Netw. Disord. 2025, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, P.I.; Ueland, P.M.; Kvalheim, G.; Lien, E.A. Determination of Choline, Betaine, and Dimethylglycine in Plasma by a High-Throughput Method Based on Normal-Phase Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2003, 49, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüls, A.; Tan, Y.; Casey, E.; Li, Z.; Gearing, M.; Levey, A.I.; Lah, J.J.; Wingo, A.P.; Jones, D.P.; Walker, D.I.; et al. Metabolic Dysregulation in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Brain Metabolomics Approach. Alzheimers Dement. 2025, 21, e70528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-Y.; Lin, Y.-R.; Tu, Y.-S.; Tseng, Y.J.; Chan, M.-H.; Chen, H.-H. Effects of Sarcosine and N, N-Dimethylglycine on NMDA Receptor-Mediated Excitatory Field Potentials. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; Qu, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, Z. New Advances in Small Molecule Drugs Targeting NMDA Receptors. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Gräslund, A.; Abrahams, J.P. Non-Chaperone Proteins Can Inhibit Aggregation and Cytotoxicity of Alzheimer Amyloid β Peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 27766–27775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, J.; Antonelli, A.C.; Afridi, A.; Vatsia, S.; Joshi, G.; Romanov, V.; Murray, I.V.J.; Khan, S.A. Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review of Pathogeneses, Novel Detection Strategies, and Potential Therapeutics. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 30, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszła, O.; Sołek, P. Misfolding and Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Protein Quality Control Machinery as Potential Therapeutic Clearance Pathways. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.T.; Awosiminiala, F.W.; Anumudu, C.K. Exploring Protein Misfolding and Aggregate Pathology in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Interventions. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolen, D.W. Effects of Naturally Occurring Osmolytes on Protein Stability and Solubility: Issues Important in Protein Crystallization. Methods 2004, 34, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahban, M.; Ahmad, F.; Piatyszek, M.A.; Haertlé, T.; Saso, L.; Saboury, A.A. Stabilization Challenges and Aggregation in Protein-Based Therapeutics in the Pharmaceutical Industry. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 35947–35963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepelnjak, M.; Velten, B.; Näpflin, N.; von Rosen, T.; Palmiero, U.C.; Ko, J.H.; Maynard, H.D.; Arosio, P.; Weber-Ban, E.; de Souza, N.; et al. In Situ Analysis of Osmolyte Mechanisms of Proteome Thermal Stabilization. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DMG | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (µm) | ΔTm (°C) | ΔHm (kcal/mol) | ΔGD° (kcal/mol) |

| 0.00 | 55.5 ± 1.1 | 85.4 ± 2.5 | 6.4 ± 0.25 |

| 50 | 56.5 ± 1.1 | 88.2 ± 2.6 | 6.8 ± 0.27 |

| 100 | 58.4 ± 1.2 | 95.6 ± 2.8 | 7.8 ± 0.31 |

| 250 | 60.1 ± 1.2 | 101.4 ± 3.1 | 8.7 ± 0.34 |

| 500 | 62.6 ± 1.3 | 107.8 ± 3.2 | 9.8 ± 0.39 |

| Site Number | Amino Acid | Site Score |

|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | Lys306, Asp307, Tyr308, Pro304 | 0.93 |

| Site 2 | Ser337, Pro359, Asp363, Pro368 | 0.81 |

| Site 3 | Pro158, Pro162, Arg72, Val73 | 0.75 |

| Site 4 | Gly118, Asp469, Val126, Ala251 | 0.69 |

| Site 5 | Gln18, Ala270, Pro7, Gln11 | 0.51 |

| Site Number | Docking Score | Glide Energy |

|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | −5.6 | −30.2 |

| Site 2 | −4.5 | −25.7 |

| Site 3 | −3.8 | −20.4 |

| Site 4 | −3.4 | −18.6 |

| Site 5 | −2.3 | −13.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Devi, A.P.; Yumlembam, S.; Singh, K.; Gupta, A.; Sarangthem, K.; Singh, L.R. Dimethylglycine as a Potent Modulator of Catalase Stability and Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biophysica 2026, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica6010002

Devi AP, Yumlembam S, Singh K, Gupta A, Sarangthem K, Singh LR. Dimethylglycine as a Potent Modulator of Catalase Stability and Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biophysica. 2026; 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica6010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleDevi, Adhikarimayum Priya, Seemasundari Yumlembam, Kuldeep Singh, Akshita Gupta, Kananbala Sarangthem, and Laishram Rajendrakumar Singh. 2026. "Dimethylglycine as a Potent Modulator of Catalase Stability and Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease" Biophysica 6, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica6010002

APA StyleDevi, A. P., Yumlembam, S., Singh, K., Gupta, A., Sarangthem, K., & Singh, L. R. (2026). Dimethylglycine as a Potent Modulator of Catalase Stability and Activity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biophysica, 6(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biophysica6010002