Caecal Volvulus: A District General Hospital Experience and Review of the Literature

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Demography

4.2. Clinical Presentation

4.3. Aetiology

4.4. Radiological Investigations

4.4.1. Conventional Radiography

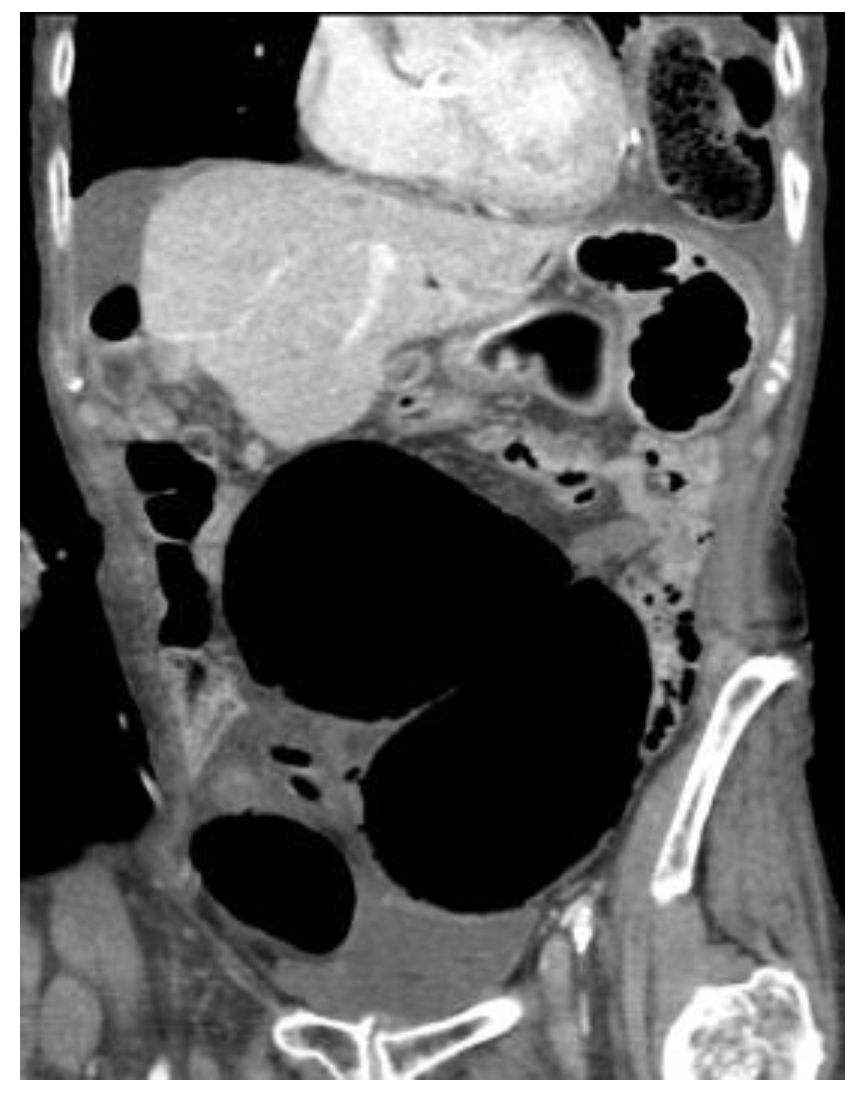

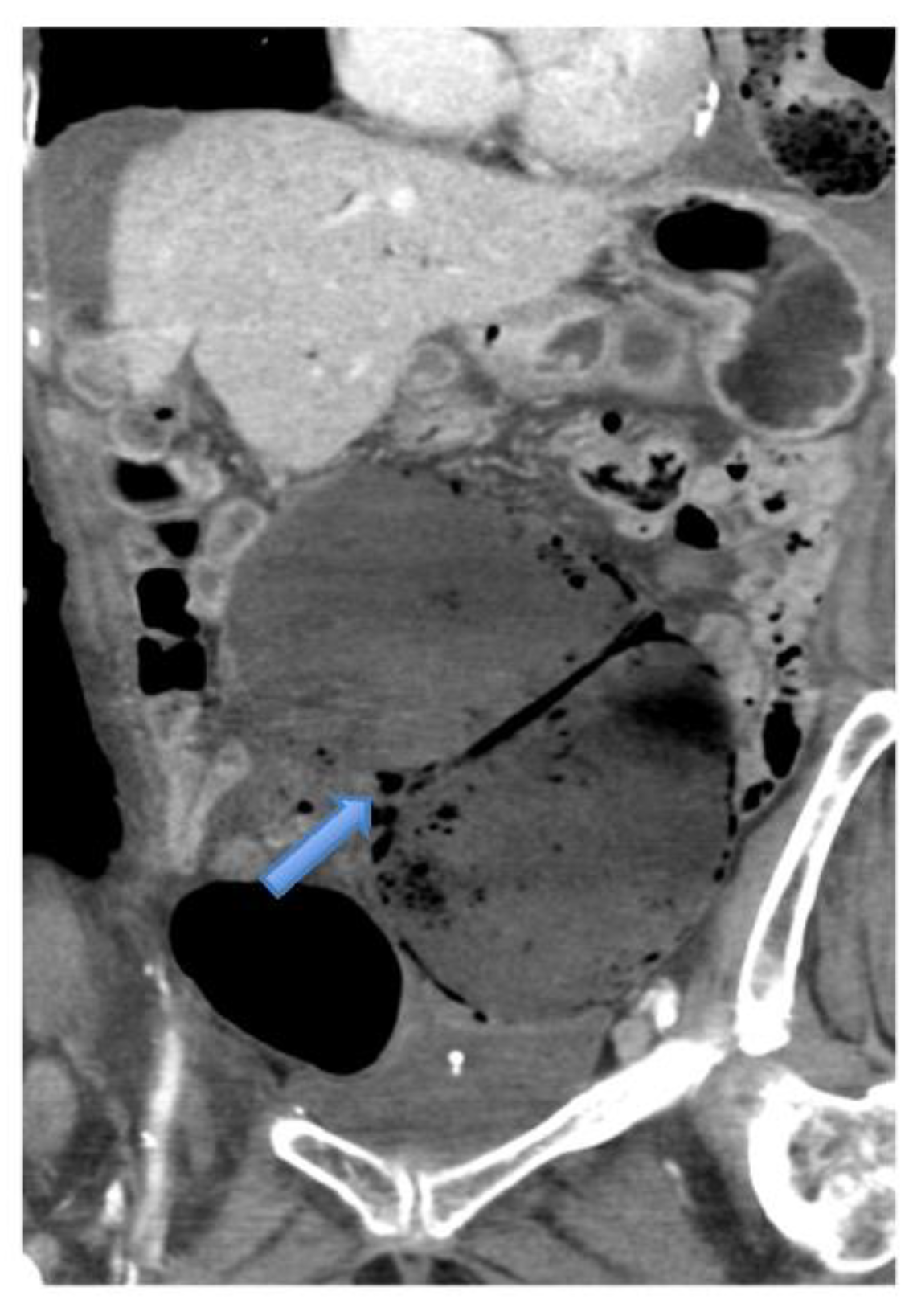

4.4.2. Computerised Tomography (CT) Scan

4.5. Management

5. Learning Points/Highlights

- Variable clinical presentation in different population

- CT scan confirms diagnosis in >90%

- Typical Radiological Signs are described

- Representative X-ray and CT images presented

- Resectional procedures are favoured

- Secondary pathology as cancer might be the cause

- Significant morbidity expected but mortality is declining.

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster Inc. Available online: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/volvulus (accessed on 14 July 2020).

- Gingold, D.; Murrell, Z. Management of colonic volvulus. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg. 2012, 25, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ballantyne, G.H.; Brandner, M.D.; Beart, R.W., Jr.; Ilstrup, D.M. Volvulus of the colon. Incidence and mortality. Ann. Surg. 1985, 202, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horesh, N.; Nadler, R.; Pery, R.; Gravetz, A.; Amitai, M.M.; Rosin, D. Surgical Treatment of Caecal Volvulus. Clin. Surg. 2017, 2, 1346. [Google Scholar]

- Consorti, E.T.; Liu, T.H. Diagnosis and treatment of caecal volvulus. Postgrad. Med. J. 2005, 81, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoor, K.; Al Hamidi, S.; Khan, A.M.; Samujh, R. Rare case of pediatric cecal volvulus. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2009, 14, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shehata, A.E.; Helal, M.A.; Ibrahim, E.A.; Magdy, B.; El Seoudy, M.; Shaban, M.; Taher, H. Cecal volvulus in a child with congenital dilated cardiomyopathy: A case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2020, 66, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, T.; Shigemori, T.; Fukaya, R.; Suzuki, H. Cecal volvulus: Report of a case and review of Japanese literature. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2009, 15, 2547–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, S.K. Acute caecal volvulus: Report of 22 cases and review of literature. Ital. J. Gastroenterol. 1993, 25, 380–384. [Google Scholar]

- Khaniya, S.; Shakya, V.C.; Koirala, R.; Pokharel, K.; Regmi, R.; Adhikary, S.; Agrawal, C.S. Caecal volvulus: A twisted tale. Trop. Doctor. 2010, 40, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, D.A.; Reasebeck, P.G.; Reasbeck, J.C.; Effeney, D.J. Caecal volvulus: Ten-year experience in an Australian teaching hospital. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 1987, 69, 283–285. [Google Scholar]

- Madiba, T.E.; Thomson, S.R. The management of cecal volvulus. Dis. Colon Rectum 2002, 45, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfer, J.A. Volvulus of the cecum. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1942, 74, 882–894. [Google Scholar]

- Donhauser, J.L.; Atwell, S. Volvulus of The Cecum: With a Review of One Hundred Cases in the Literature and a Report of Six New Cases. Arch. Surg. 1949, 58, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, S.A.; Ravichandran, D.; Wilmink, A.B.M.; Baker, A.; Purushotham, A.D. Cecal Volvulus Occurring after Laparoscopic Appendectomy. JSLS 2001, 5, 317–318. [Google Scholar]

- Caecal Volvulus Following Left-Side Laparoscopic Retroperitoneal Nephroureterectomy|BMJ Case Reports. Available online: https://casereports.bmj.com/content/12/7/e228878 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Rakinic, J. The ASCRS Textbook of Colon and Rectal Surgery, 2nd ed.; Beck, D.E., Roberts, P.L., Saclaride, T.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 395–406. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovici, R.; Simansky, D.A.; Kaplan, O.; Mavor, E.; Manny, J. Cecal volvulus. Dis. Colon Rectum 1990, 33, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figiel, L.S.; Figiel, S.J. Volvulus of the cecum and ascending colon. Radiology 1953, 61, 496–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.S. Further radiological observations in caecal volvulus. Clin. Radiol. 1980, 31, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Mills, J.O. Caecal volvulus: A frequently missed diagnosis? Clin. Radiol. 1984, 35, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.D.; Odland, M.D.; Bubrick, M.P. Experience with colonic volvulus. Dis. Colon Rectum 1989, 32, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, B.; Hindman, N.; Johnson, E.; Rosenkrantz, A.B. Utility of CT Findings in the Diagnosis of Cecal Volvulus. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 209, 762–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblat, J.M.; Rozenblit, A.M.; Wolf, E.L.; DuBrow, R.A.; Den, E.I.; Levsky, J.M. Findings of Cecal Volvulus at CT. Radiology 2010, 256, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara, C.S.; Wilson, T.H.; Stonesifer, G.L.; Cameron, J.L. Cecal volvulus: Analysis of 50 patients with long-term follow-up. Curr. Surg. 1980, 37, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R.; Welch, G.H. Acute volvulus of the right colon: An analysis of 69 patients. World J. Surg. 1986, 10, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzulli, P.; Maurer, C.A.; Netzer, P.; Büchler, M.W. Preoperative colonoscopic derotation is beneficial in acute colonic volvulus. Dig. Surg. 2002, 19, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirol, F.T. Cecocolic Torsion: Classification, Pathogenesis, and Treatment. JSLS 2005, 9, 328–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, Z.M.; Evans, C.H. Volvulus. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 98, 973–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Tovar, J.; Calero García, P.; Morales Castiñeiras, V.; Martínez Molina, E. Caecal volvulus: Presentation of 18 cases and review of literature. Cir. Esp. 2009, 85, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostergaard, E.; Halvorsen, J.F. Volvulus of the caecum. An evaluation of various surgical procedures. Acta Chir. Scand. 1990, 156, 629–631. [Google Scholar]

- Majeski, J. Operative therapy for cecal volvulus combining resection with colopexy. Am. J. Surg. 2005, 189, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R.S.; Catto, J. Cecal volvulus: A case for non-resectional therapy. Arch. Surg. 1980, 115, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuech, J.J.; Becouarn, G.; Cattan, F.; Arnaud, J.P. Volvulus of the right colon. Plea for right hemicolectomy. Apropos of a series of 23 cases. J. Chir. 1996, 133, 267–269. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Number, (Range or Percentage) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | 16 | |

| Gender, M:F | 5:11 | |

| Median Age, years | 64 (33–80) |

| Variables | Number, (Range or Percentage) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| ASA Grade | ||

| I | 5 (31.2%) | |

| II | 3 (18.8%) | |

| III | 7 (43.7%) | |

| IV | 1 (6.3%) | |

| Co-morbidities | Hypertension, ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, COPD, and depression. | |

| None | 5 (31.2%) | |

| Single or Multiple | 11 (68.8%) | |

| Use of psychotropic drugs | 6 (37.5%) | |

| Abdomen pain, distension, and vomiting | 16 (100%) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery | Nephrectomy, laparoscopic sterilisation, sigmoid colectomy, hysterectomy. | |

| None | 11 (68.7%) | |

| One | 3 | |

| Multiple | 2 | |

| History of large bowel volvulus | 1 (6.8%) | Sigmoid resection for volvulus 4 years before this admission. |

| Initial diagnosis by emergency physician: | ||

| Large bowel obstruction | 6 (37.5%) | |

| Small bowel obstruction | 2 (12.5%) | |

| Others | 8 (50.0%) | |

| Acute appendicitis | 2 | |

| Post-op collection | 1 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | |

| Viscus perforation | 1 | |

| Pancreatitis | 1 | |

| Biliary colic | 1 | |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 |

| Variables | Number, (Range or Percentage) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal radiograph | 11 (68.75%) | Five patients had CT as the only imaging. |

| Non-specific bowel loops/SBO | 5 (46%) | |

| Classical single loop of large bowel | 6 (54%) | |

| CT Abdomen and pelvis | 15 | One patient operated without CT. |

| CV not described | 1 | |

| CV correctly identified | 14 (93.3%) | |

| Caecal diameter >10 cm | 10 (67%) | |

| Whirl sign | 12 (80%) | |

| Split-wall sign | 13 (86.6%) | |

| X-marks-the-spot sign | 14 (93.3%) | |

| Double transition point | 13 (86.6%) | |

| Ileocaecal twist | 13 (86.6%) | |

| Central appendix | 11 (73.3%) |

| Variables | Number, (Range or Percentage) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | ||

| Conservative Management | 1 (6.25%) | |

| Surgery | 15 (93.7%) | |

| Laparoscopic | 1 (6.25%) | |

| Open | 14 (93.3%) | |

| Intraoperative Findings | ||

| Gangrenous Caecum | 1 (6.7%) | |

| Patchy ischaemia | 12 (80%) | |

| No ischaemia | 2 | |

| Procedure | ||

| Resection and primary anastomosis | 14 (93.3%) | |

| Resection, ileostomy, and mucous fistula | 1 | |

| Complications | ||

| 30-day mortality in conservatively managed | 1 (100%) | |

| 30-day mortality in operated patients | None | |

| Uneventful recovery | 3 (20%) | |

| Morbidity | 12 (80%) | |

| Postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo) | ||

| I | 5 | |

| II | 3 | |

| III | 7 | |

| IV | 1 | |

| Major Morbidity | ||

| Anastomosis Leak | 2 | |

| CT guided Drainage | 1 | |

| Re-operation and ileostomy | 1 | |

| Reoperation | 3 | |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 | |

| Fascial Dehiscence | 1 | |

| Bowel Obstruction/suspicion of ischaemia | 1 | |

| Median Length of stay (days) | 10 (1–49) | |

| Histopathology | ||

| Low grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm (LAMN) | 1 | |

| Tubular Adenoma | 1 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 | |

| No additional pathology | 12 | |

| Median follow-up | 20 months (6–31) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pangeni, A.; Chowdhury, A.; Rai, S.; Colledge, J.Y.; Shrestha, A.K. Caecal Volvulus: A District General Hospital Experience and Review of the Literature. Surgeries 2022, 3, 78-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries3020010

Pangeni A, Chowdhury A, Rai S, Colledge JY, Shrestha AK. Caecal Volvulus: A District General Hospital Experience and Review of the Literature. Surgeries. 2022; 3(2):78-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries3020010

Chicago/Turabian StylePangeni, Anang, Ashim Chowdhury, Sujata Rai, Jann Yee Colledge, and Ashish Kiran Shrestha. 2022. "Caecal Volvulus: A District General Hospital Experience and Review of the Literature" Surgeries 3, no. 2: 78-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries3020010

APA StylePangeni, A., Chowdhury, A., Rai, S., Colledge, J. Y., & Shrestha, A. K. (2022). Caecal Volvulus: A District General Hospital Experience and Review of the Literature. Surgeries, 3(2), 78-91. https://doi.org/10.3390/surgeries3020010