In Patients with Dysimmune Motor and Sensorimotor Mononeuropathies, the Degree of Nerve Swelling Correlates with Clinical and Electrodiagnostic Findings

Abstract

1. Introduction

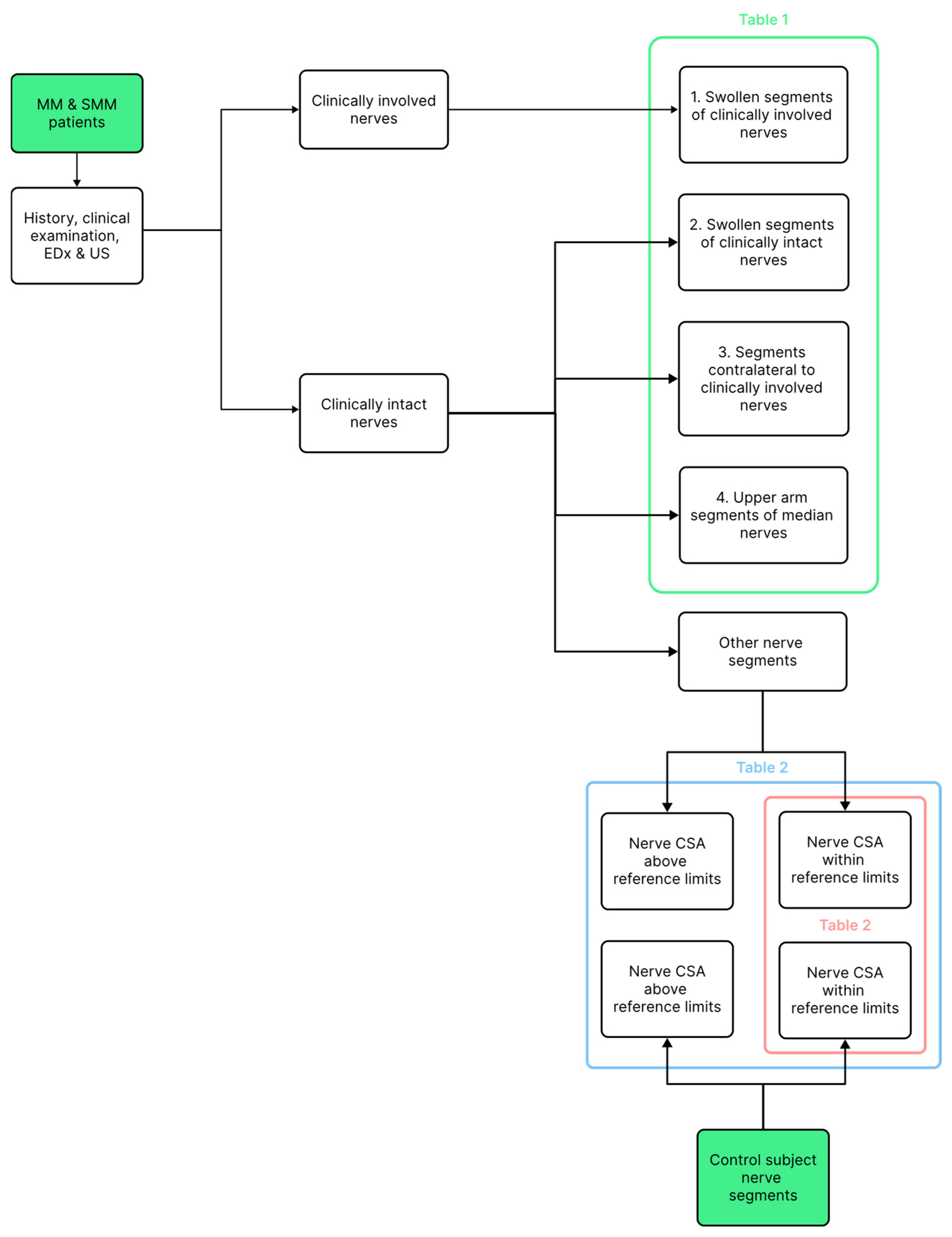

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Controls

2.2. History and Clinical Neurologic Examination

2.3. Electrodiagnostic Studies

2.4. Ultrasonography (US)

2.5. Statistics

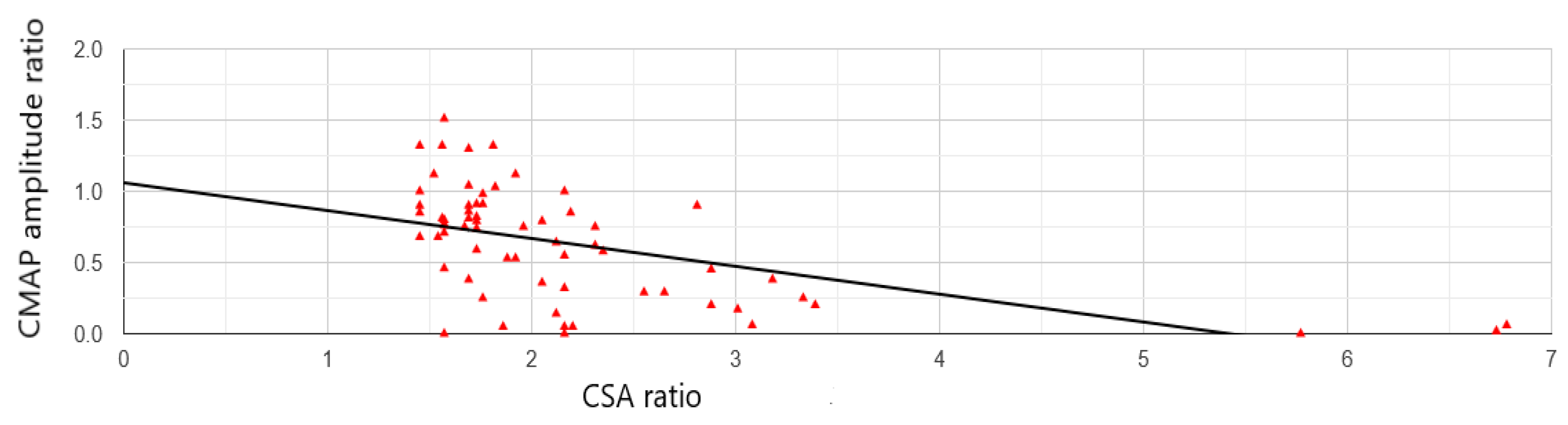

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIDP | Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy |

| CMAP | Compound muscle action potential |

| CSA | Cross-sectional area |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| EDx | Electrodiagnostic |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| MM | Motor mononeuropathy |

| MMN | Multifocal motor neuropathy |

| MRC | Medical Research Council |

| NCSs | Nerve conduction studies |

| SMM | Sensorimotor mononeuropathy |

| SNAP | Sensory nerve action potential |

| US | Ultrasonography |

References

- Van den Bergh, P.Y.K.; van Doorn, P.A. European Academy of Neurology/Peripheral Nerve Society guideline on diagnosis and treatment of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy: Report of a joint Task Force-Second revision. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 3556–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podnar, S. Ultrasonographic abnormalities in clinically unaffected nerves of patients with nonvasculitic motor and sensorimotor mononeuropathies. Muscle Nerve 2024, 70, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beekman, R.; Berg, L.H.v.D.; Franssen, H.; Visser, L.H.; van Asseldonk, J.; Wokke, J.H. Ultrasonography shows extensive nerve enlargements in multifocal motor neuropathy. Neurology 2005, 65, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, A.; Décard, B.F.; Bischof, A.; Axer, H. Ultrasound of the peripheral nerves in systemic vasculitic neuropathies. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014, 347, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arányi, Z.; Csillik, A.; Dévay, K.; Rosero, M.; Barsi, P.; Böhm, J.; Schelle, T. Ultrasonography in neuralgic amyotrophy: Sensitivity, spectrum of findings, and clinical correlations. Muscle Nerve 2017, 56, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, M. Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 5th ed.; Saunders Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Omejec, G.; Podnar, S. Precise localization of ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 126, 2390–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podnar, S.; Sarafov, S.; Tournev, I.; Omejec, G.; Zidar, J. Peripheral nerve ultrasonography in patients with transthyretin amyloidosis. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2017, 128, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisse, A.L.; Katsanos, A.H.; Gold, R.; Pitarokoili, K.; Krogias, C. Cross-sectional area reference values for peripheral nerve ultrasound in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis-Part I: Upper extremity nerves. Eur. J. Neurol. 2021, 28, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Kingdom. Statistical Tests and Calculators [Internet]; *Statistics Kingdom*: Melbourne, Australia, 2017–2025. Available online: https://www.statskingdom.com/ (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- van Rosmalen, M.; Lieba-Samal, D.; Pillen, S.; van Alfen, N. Ultrasound of peripheral nerves in neuralgic amyotrophy. Muscle Nerve 2019, 59, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.A.; Sumner, A.J.; Brown, M.J.; Asbury, A.K. Multifocal demyelinating neuropathy with persistent conduction block. Neurology 1982, 32, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viala, K.; Renié, L.; Maisonobe, T.; Béhin, A.; Neil, J.; Léger, J.M.; Bouche, P. Follow-up study and response to treatment in 23 patients with Lewis-Sumner syndrome. Brain 2004, 127, 2010–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Federation of Neurological Societies/Peripheral Nerve; Society guideline on management of multifocal motor neuropathy. Report of a joint task force of the European Federation of Neurological Societies and the Peripheral Nerve Society--first revision. J. Peripher. Nerve Syst. 2010, 15, 295–301.

- Kerasnoudis, A.; Pitarokoili, K.; Behrendt, V.; Gold, R.; Yoon, M.S. Correlation of nerve ultrasound, electrophysiological and clinical findings in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. J. Neuroimaging 2015, 25, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Niu, J.; Liu, T.; Ding, Q.; Wu, S.; Guan, Y.; Cui, L.; Liu, M. Conduction Block and Nerve Cross-Sectional Area in Multifocal Motor Neuropathy. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Ding, Q.; Cui, L.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M. Serial nerve ultrasound and motor nerve conduction studies in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2019, 60, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.H.; Cho, C.S.; Yang, K.-S.; Seok, H.Y.; Kim, B.-J. Pattern analysis of nerve enlargement using ultrasonography in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goedee, H.S.; van der Pol, W.L.; van Asseldonk, J.-T.H.; Franssen, H.; Notermans, N.C.; Vrancken, A.J.; van Es, M.A.; Nikolakopoulos, S.; Visser, L.H.; van den Berg, L.H. Diagnostic value of sonography in treatment-naive chronic inflammatory neuropathies. Neurology 2017, 88, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerasnoudis, A.; Pitarokoili, K.; Behrendt, V.; Gold, R.; Yoon, M.S. Multifocal motor neuropathy: Correlation of nerve ultrasound, electrophysiological, and clinical findings. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2014, 19, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podnar, S. Length of affected nerve segment in ulnar neuropathies at the elbow. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022, 133, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Nerve CSA Ratio Median (Range) | p-Value: * < 0.01, ** < 0.001 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Clinically involved nerve segments | 21 | 2.35 (1.54–6.78) | 1 vs. 2 *, 1 vs. 3 ** |

| 2. Swollen clinically uninvolved nerve segments | 18 | 1.76 (1.56–2.71) | 2 vs. 3 = 0.17, |

| 3. Nerves contralateral to the involved nerves | 20 | 1.62 (0.91–4.07) | 3 vs. 4 = 0.21 |

| 4. Median nerves in the upper arm | 42 | 1.45 (0.96–2.05) | 1 vs. 4 **, 2 vs. 4 * |

| All Nerve Segments | Non-Swollen Nerve Segments | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Controls | Patients | Controls | |||||||

| N | Median (25–75 Perc.) | N | Median (25–75 Perc.) | p-Value | N | Median (25–75 Perc.) | N | Median (25–75 Perc.) | p-Value | |

| Median wrist | 44 | 13 (11–15.25) | 50 | 10 (8–11.75) | <0.001 | 12 | 11 (10–11) | 37 | 9 (8–10) | <0.001 |

| Median forearm | 44 | 8 (7–9) | 50 | 7 (6–8) | <0.001 | 38 | 7.50 (7–8.75) | 47 | 6 (6–8) | 0.002 |

| Median elbow | 44 | 12 (10–14) | 50 | 11.50 (10–13) | <0.001 | 42 | 12 (10–14) | 48 | 11 (10–13) | <0.001 |

| Median upper arm | 44 | 11.50 (10–13) | 50 | 7 (6–8) | <0.001 | 22 | 11 (9–11) | 49 | 7 (6–8) | <0.001 |

| Ulnar wrist | 43 | 7 (6–8) | 50 | 6 (5–7) | 0.008 | 43 | 7 (6–8) | 49 | 6 (5–7) | 0.004 |

| Ulnar forearm | 42 | 9 (8–9.75) | 50 | 6 (5–7) | <0.001 | 31 | 8 (7–9) | 49 | 6 (5–7) | <0.001 |

| Ulnar elbow | 43 | 11 (8.50–12.50) | 50 | 8 (7–9.75) | <0.001 | 21 | 8 (8–9) | 44 | 8 (7–9) | 0.38 |

| Ulnar upper arm | 43 | 8 (7–10) | 50 | 10 (9–11) | <0.001 | 30 | 7.50 (7–8) | 23 | 9 (8–9) | <0.001 |

| Fibular head | 20 | 11 (10–12.50) | 48 | 10 (8–12) | 0.038 | 15 | 11 (9.50–11) | 45 | 10 (8–11) | 0.02 |

| Fibular knee | 20 | 8 (6.75–9) | 48 | 7 (6–9.25) | 0.41 | 20 | 8 (6.75–9) | 44 | 7 (6–8) | 0.10 |

| Tibial ankle | 16 | 13 (12–13.25) | 48 | 11 (9–13.25) | 0.053 | 16 | 13 (12–13.25) | 46 | 11 (9–12.75) | 0.015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Podnar, S. In Patients with Dysimmune Motor and Sensorimotor Mononeuropathies, the Degree of Nerve Swelling Correlates with Clinical and Electrodiagnostic Findings. NeuroSci 2026, 7, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010005

Podnar S. In Patients with Dysimmune Motor and Sensorimotor Mononeuropathies, the Degree of Nerve Swelling Correlates with Clinical and Electrodiagnostic Findings. NeuroSci. 2026; 7(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010005

Chicago/Turabian StylePodnar, Simon. 2026. "In Patients with Dysimmune Motor and Sensorimotor Mononeuropathies, the Degree of Nerve Swelling Correlates with Clinical and Electrodiagnostic Findings" NeuroSci 7, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010005

APA StylePodnar, S. (2026). In Patients with Dysimmune Motor and Sensorimotor Mononeuropathies, the Degree of Nerve Swelling Correlates with Clinical and Electrodiagnostic Findings. NeuroSci, 7(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010005