Exploring the Neural Pathways of Faith: A Review and Case Study on Hyperreligiosity in Epilepsy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Review the historical and clinical literature on the relationship between epilepsy and religion.

- Describe the different forms of manifestation of hyperreligiosity in TLE.

- Analyze the main neurobiological models proposed.

- Present an illustrative clinical case, documenting a structural alteration of the uncinate fasciculus in a patient with episodes of religious conviction.

2. Epilepsy and Religion Throughout History

2.1. Antiquity: From the Divine to the Pathological

2.2. Middle Ages and Renaissance

2.3. Paradigmatic Cases in Religious History

- The Apostle Paul: His visions, recounted in the letters of the New Testament, such as the rapture to the “third heaven” (2 Corinthians 12:2–4), have been reinterpreted by modern neurology as possible psychic auras characteristic of temporal epilepsy [2]. This interpretation is further supported by Brorson and Brewer [15], who provide a detailed neurological reassessment of Paul’s visionary episodes, arguing that several features are compatible with psychic auras characteristic of temporal lobe epilepsy.

- Saint Teresa of Ávila: Her mystical ecstasies, described in detail in The Book of Her Life, display features compatible with “ecstatic epilepsy”: alterations of consciousness, sensations of levitation, and union with God [3]. A recent neurological reassessment by Huberfeld et al. [16] further explores the ecstatic episodes described by Teresa of Ávila, arguing that several phenomenological elements may align with temporal lobe epileptic activity while acknowledging the difficulty of distinguishing between epilepsy and genuine mystical ecstasy.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky: The Russian novelist suffered from temporal epilepsy and described in his works experiences of absolute fullness preceding seizures. Gastaut [7] described this as the clearest example of ecstatic epilepsy in literature.

2.4. Modern Interpretations

3. Phenomenology of Hyperreligiosity in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

3.1. Ictal Experiences

- Subjective sensations of divine presence: patients describe the certainty that a transcendent entity is next to them, without requiring vision or voice.

- Religious visions: appearance of images with spiritual content, such as angelic figures, saints, or sacred symbols.

- Mystical or emotional ecstasy: feelings of unity with the universe, absolute fullness, or indescribable peace.

- Auditory phenomena: voices transmitting religious messages or divine commands.

3.2. Postictal Experiences

- Religious delusions: beliefs of divine mission, messianic convictions, or persecutory ideas with spiritual content.

- Prolonged mystical states: sensations of enlightenment, certainty of having received revelations, or a compulsive need to preach.

- Thought disturbances: discourse centered on transcendental topics, with heavy emotional charge and poor critical capacity.

3.3. Interictal Religiosity

- Hyperreligiosity: intense convictions, increased spiritual practice, sense of transcendent mission.

- Hypergraphia: compulsion to write, often on philosophical, moral, or religious topics.

- Moralizing and circumstantial discourse: tendency to elaborate lengthy ethical and spiritual reasoning, with difficulty in synthesizing.

- Decreased sexual interest: displacement of libido toward spiritual or abstract interests.

4. Neurobiological Models of Hyperreligiosity

4.1. Limbic Marker Hypothesis

- Sense of supreme reality: the patient perceives the episode as more “real” than everyday life.

- Unity and harmony: integration of internal and external stimuli into a totalizing experience.

- Ecstasy and serenity: intense emotions of peace, joy, or fullness.

- Ineffability: difficulty or impossibility of verbally expressing the experience.

4.2. Theory of Mind and Brain Networks

4.2.1. Theory of Mind (ToM)

4.2.2. Triple Network Model (TNM)

- Default Mode Network (DMN): involves the medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and precuneus. It is activated during introspection, autobiographical memory, and self-referential thought. In religion, it contributes to spiritual reflection and the sense of continuity of the self.

- Salience Network (SN): includes the anterior insula and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex. It detects relevant internal and external stimuli, granting them emotional priority. In hyperreligiosity, it may attribute transcendent value to neutral perceptions.

- Central Executive Network (CEN): formed by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal regions. It is responsible for cognitive control and critical evaluation. Its dysfunction in pathological contexts may favor the uncritical acceptance of mystical experiences.

4.2.3. Clinical and Experimental Evidence

- In bipolar disorder, manic episodes are associated with hyperactivation of the DMN, which may generate grandiose religious ideas [20].

- In schizophrenia, ToM and SN dysfunction contribute to the genesis of delusions with religious content [18].

- In studies with psilocybin and other psychedelics, disruption of DMN connectivity correlates with experiences of ego dissolution and mystical visions [21].

4.3. The Uncinate Fasciculus as a Possible Integrative Pathway

- Bidirectionality: allows emotional stimuli from the limbic system to be modulated by frontal regions.

- Valuation and meaning: facilitates perceptual experiences, acquiring affective and moral connotation.

4.3.1. Anatomical and Functional Evidence

4.3.2. Clinical Studies

4.3.3. Relation to Hyperreligiosity

5. Illustrative Clinical Case

5.1. Background

5.2. Clinical History

5.3. Complementary Studies

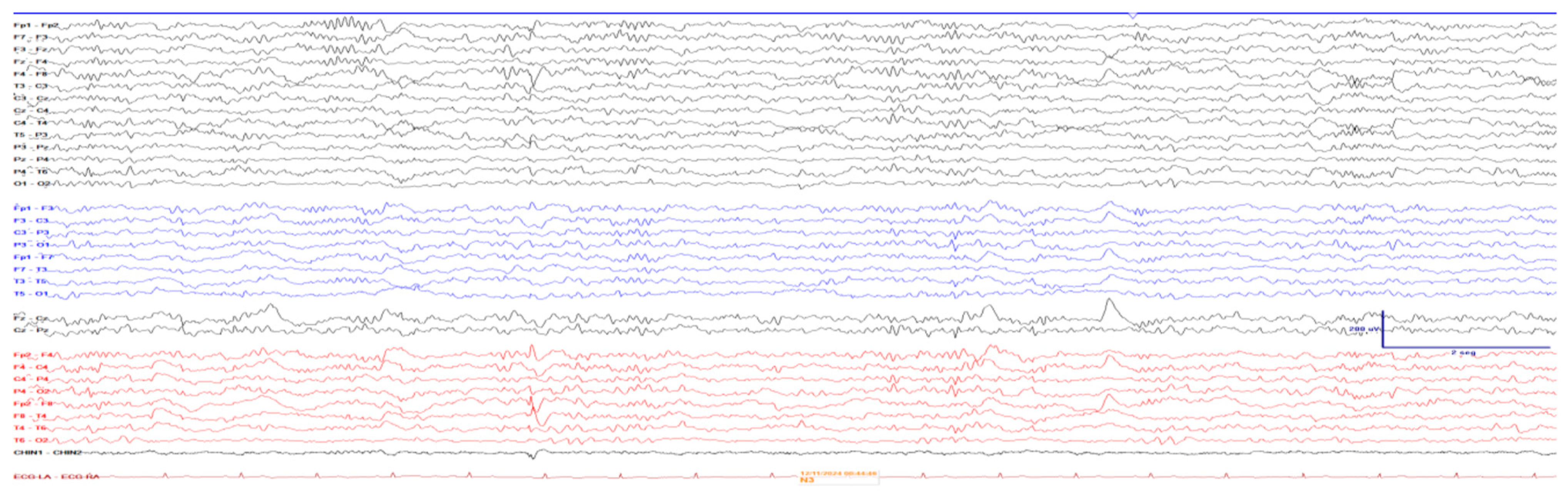

5.3.1. Video-EEG

5.3.2. Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) Tractography

5.4. Surgical Intervention

5.5. Postoperative Course

- The paroxysmal episodes of divine conviction were directly related to epileptic activity and alteration of the uncinate fasciculus.

- The patient’s spiritual transformation persisted beyond the cessation of seizures, reflecting how intense ictal experiences can induce lasting changes in the belief system.

5.6. Case Commentary

- At the ictal level, the patient presented with brief episodes of absolute certainty of the existence of God.

- At the interictal level, she developed sustained religiosity that persisted even after surgery.

- The correlation with alteration of the right uncinate fasciculus supports the hypothesis that this white matter tract may act as a key modulator in the propagation of epileptic activity toward frontal regions involved in meaning attribution.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramachandran, V.S.; Blakeslee, S. Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind; Wil-liam Morrow: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Landsborough, D. St Paul and temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1987, 50, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albea, E.G. The ecstatic epilepsy of Teresa of Jesus. Rev. Neurol. 2003, 37, 879–887. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Devinsky, O.; Lai, G. Spirituality and Religion in Epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2008, 12, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bear, D.M.; Fedio, P. Quantitative Analysis of Interictal Behavior in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Arch. Neurol. 1977, 34, 454–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waxman, S.G.; Geschwind, N. The Interictal Behavior Syndrome of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1975, 32, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gastaut, H. Fyodor Mikhailovitch Dostoevski’s Involuntary Contribution to the Symptomatology and Prognosis of Epilepsy. Epilepsia 1978, 19, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saver, J.L.; Rabin, J. The neural substrates of religious experience. J. Neuropsychiatry 1997, 9, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gschwind, M.; Picard, F. Ecstatic Epileptic Seizures: A Glimpse into the Multiple Roles of the Insula. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temkin, O. The Falling Sickness: A History of Epilepsy from the Greeks to the Beginnings of Modern Neurology; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, S. Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brigo, F.; Trinka, E.; Brigo, B.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Ragnedda, G.; Nardone, R.; Martini, M. Epilepsy in Hildegard of Bingen’s writings: A comprehensive overview. Epilepsy Behav. 2018, 80, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildkrout, B. What caused Joan of Arc’s neuropsychiatric symptoms? Medical hypotheses from 1882 to 2016. J. Hist. Neurosci. 2023, 32, 332–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, J.; Bachrach, B. The Mystic Mind: The Psychology of Medieval Mystics and Ascetics; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brorson, J.R.; Brewer, K. St Paul and temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1988, 51, 886–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huberfeld, G.; Pallud, J.; Drouin, E.; Hautecoeur, P. On St Teresa of Avila’s mysticism: Epilepsy and/or ecstasy? Brain A J. Neurol 2022, 145, 2621–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, M.R. The Psychoses of Epilepsy; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/1991-97586-000.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Menon, B. Towards a new model of understanding—The triple network, psychopathology and the structure of the mind. Med. Hypotheses 2019, 133, 109385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, P.; Grafman, J. Advances in brain and religion studies: A review and synthesis of recent representative studies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1495565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Du, J.-L.; Fang, X.-Y.; Ni, L.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-Y.; Yan, W.; Lu, S.-P.; Zhang, R.-R.; Xie, S.-P. Shared and distinct structural brain alterations and cognitive features in drug-naïve schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 82, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollenweider, F.X.; Preller, K.H. Psychedelic drugs: Neurobiology and potential for treatment of psychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, C.; Iacoboni, M.; Gordon, C.; Proksch, S.; Balasubramaniam, R. Posterior medial frontal cortex and threat-enhanced religious belief: A replication and extension. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2020, 15, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nencha, U.; Spinelli, L.; Vulliemoz, S.; Seeck, M.; Picard, F. Insular Stimulation Produces Mental Clarity and Bliss. Ann. Neurol. 2021, 91, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Der Heide, R.J.; Skipper, L.M.; Klobusicky, E.; Olson, I.R. Dissecting the uncinate fasciculus: Disorders, controversies and a hypothesis. Brain 2013, 136, 1692–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, S.; Sasaki, M.; Kanbara, Y.; Inoue, T.; Hirooka, R.; Ogawa, A. Feasibility of 1.6-mm isotropic voxel diffusion tensor tractography in depicting limbic fibers. Neuroradiology 2007, 50, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heimer, L.; Van Hoesen, G.; Trimble, M. The Anatomy of Neuropsychiatry: The New Anatomy of the Basal Forebrain and and Its Implication for the Neuropsychiatric Illness, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 9780123742391. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, K.; Henderson, L.; Yim, M.; Hsu, E.; Dhaliwal, R. Diffusion Tensor Imaging Investigation of Uncinate Fasciculus Anatomy in Healthy Controls: Description of a Subgenual Stem. Neuropsychobiology 2017, 75, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudebeck, P.H.; Rich, E.L. Orbitofrontal cortex. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R1083–R1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, J.-C.; Koechlin, E.; Tierney, M.; Grafman, J. Damage to the Fronto-Polar Cortex Is Associated with Impaired Multitasking. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeling, U.; Cramon, D.V. Topography of the uncinate fascicle and adjacent temporal fiber tracts. Acta Neurochir. 1992, 115, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, J.; Zuo, J.X.; Lyall, A.E.; Makris, N.; Kikinis, Z.; Bouix, S.; Pasternak, O.; Fredman, E.; Duskin, J.; Goldstein, J.M.; et al. Tractography Analysis of 5 White Matter Bundles and Their Clinical and Cognitive Correlates in Early-Course Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2016, 42, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Miranda, J.C.; Pathak, S.; Engh, J.; Jarbo, K.; Verstynen, T.; Yeh, F.-C.; Wang, Y.; Mintz, A.; Boada, F.; Schneider, W.; et al. High-Definition Fiber Tractography of the Human Brain. Neurosurgery 2012, 71, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, R.J.; Paloutzian, R.F.; Angel, H.-F. From Believing to Belief: A General Theoretical Model. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2018, 30, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-A.; Ko, M.-A.; Choi, E.-J.; Jeon, J.-Y.; Ryu, H.U. High spirituality may be associated with right hemispheric lateralization in Korean adults living with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. EB 2017, 76, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmstaedter, C.; Witt, J.-A. Cognitive outcome of antiepileptic treatment with levetiracetam versus carbamazepine monotherapy: A non-interventional surveillance trial. Epilepsy Behav. EB 2010, 18, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; McCormack, M.; Patel, S.; Stapleton, C.; Bobbili, D.; Krause, R.; Depondt, C.; Sills, G.J.; Koeleman, B.P.; Striano, P.; et al. A pharmacogenomic assessment of psychiatric adverse drug reactions to levetiracetam. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1563–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wang, X. Levetiracetam induces severe psychiatric symptoms in people with epilepsy. Seizure J. Br. Epilepsy Assoc. 2024, 116, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bazarra Castro, G.J.; Martínez Macho, C.; Mantecón Zorrilla, R.; Barbero Pablos, E.; Torres Díaz, C.V.; Fernández-Alén, J.A.; Gil Simoes, R. Exploring the Neural Pathways of Faith: A Review and Case Study on Hyperreligiosity in Epilepsy. NeuroSci 2026, 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010004

Bazarra Castro GJ, Martínez Macho C, Mantecón Zorrilla R, Barbero Pablos E, Torres Díaz CV, Fernández-Alén JA, Gil Simoes R. Exploring the Neural Pathways of Faith: A Review and Case Study on Hyperreligiosity in Epilepsy. NeuroSci. 2026; 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleBazarra Castro, Guillermo José, Carlos Martínez Macho, Ricardo Mantecón Zorrilla, Enrique Barbero Pablos, Cristina V. Torres Díaz, Jose Antonio Fernández-Alén, and Ricardo Gil Simoes. 2026. "Exploring the Neural Pathways of Faith: A Review and Case Study on Hyperreligiosity in Epilepsy" NeuroSci 7, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010004

APA StyleBazarra Castro, G. J., Martínez Macho, C., Mantecón Zorrilla, R., Barbero Pablos, E., Torres Díaz, C. V., Fernández-Alén, J. A., & Gil Simoes, R. (2026). Exploring the Neural Pathways of Faith: A Review and Case Study on Hyperreligiosity in Epilepsy. NeuroSci, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010004