Disparities in Spinal Muscular Atrophy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2018–2023

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

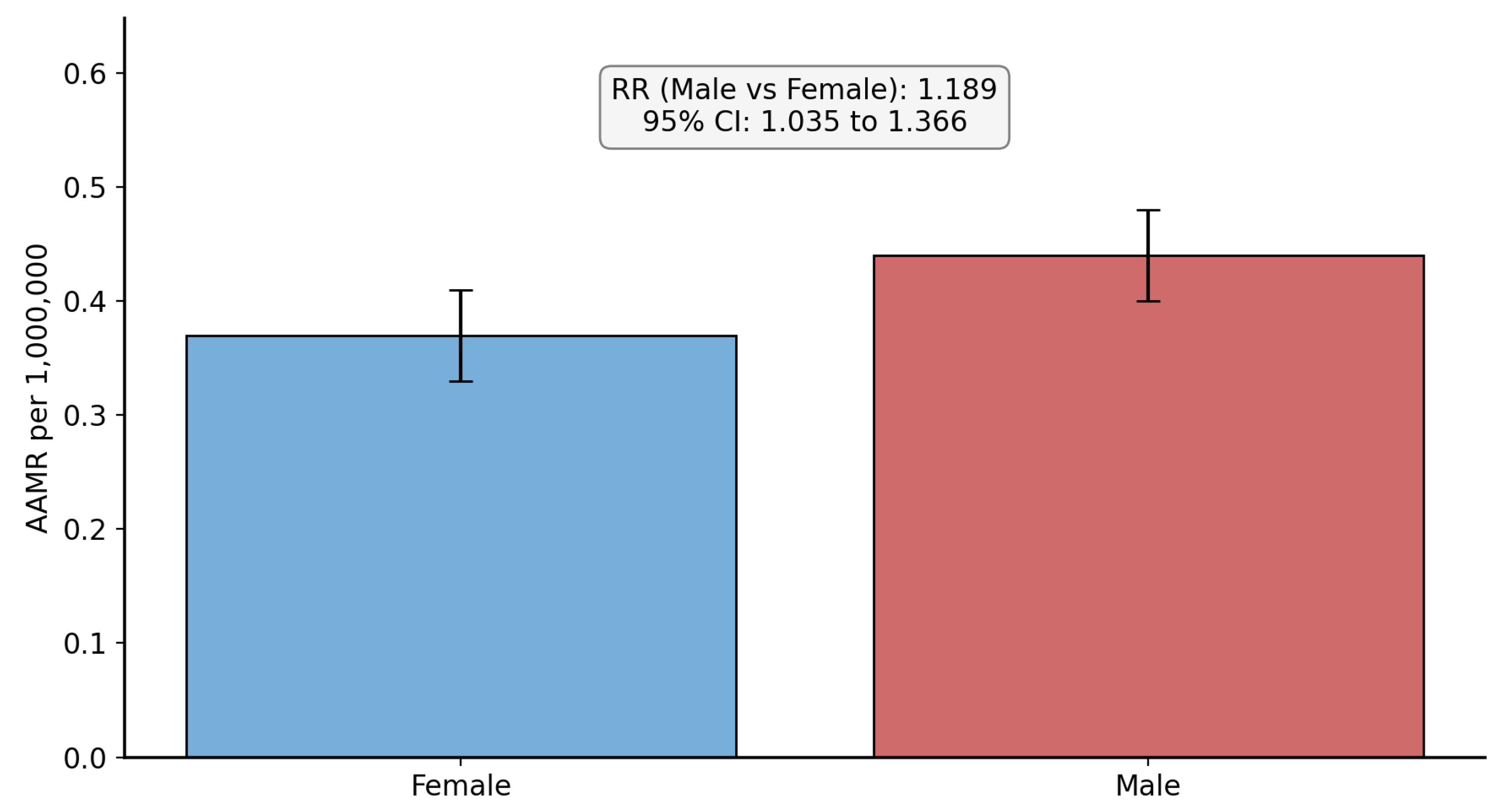

3.1. Overall Mortality and Sex-Based Disparities

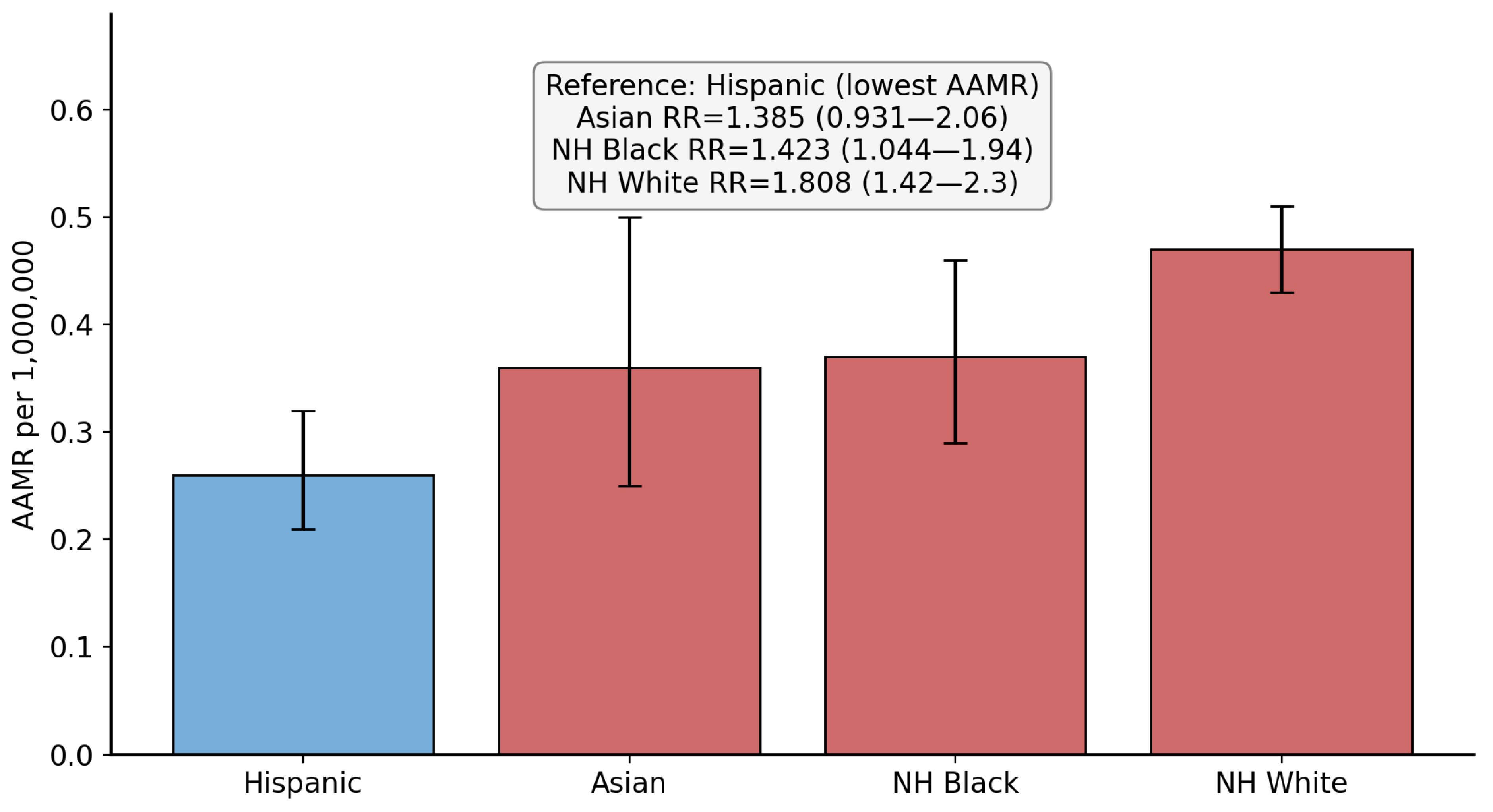

3.2. Race/Ethnicity-Based Disparities

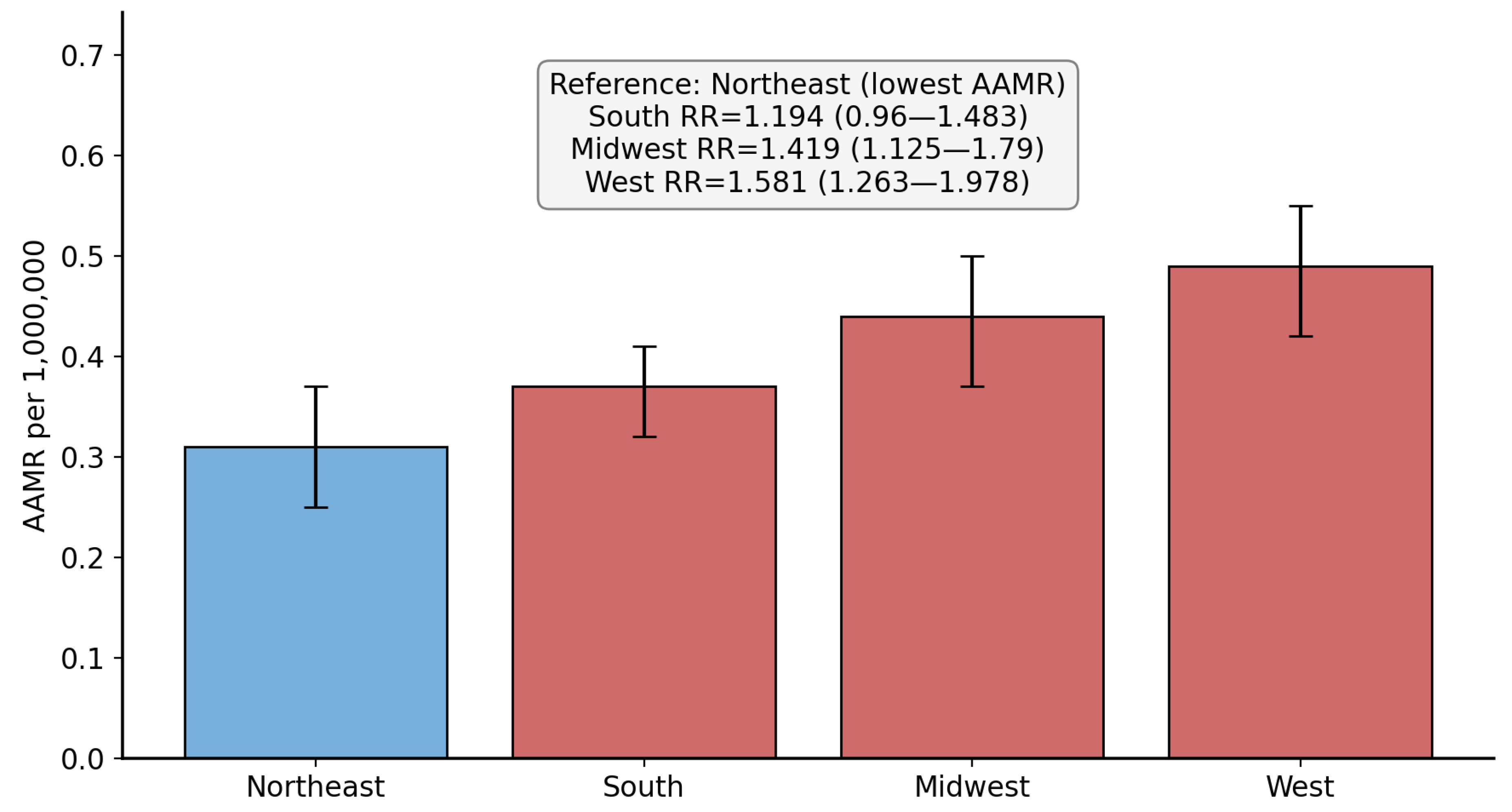

3.3. Region-Based Disparities

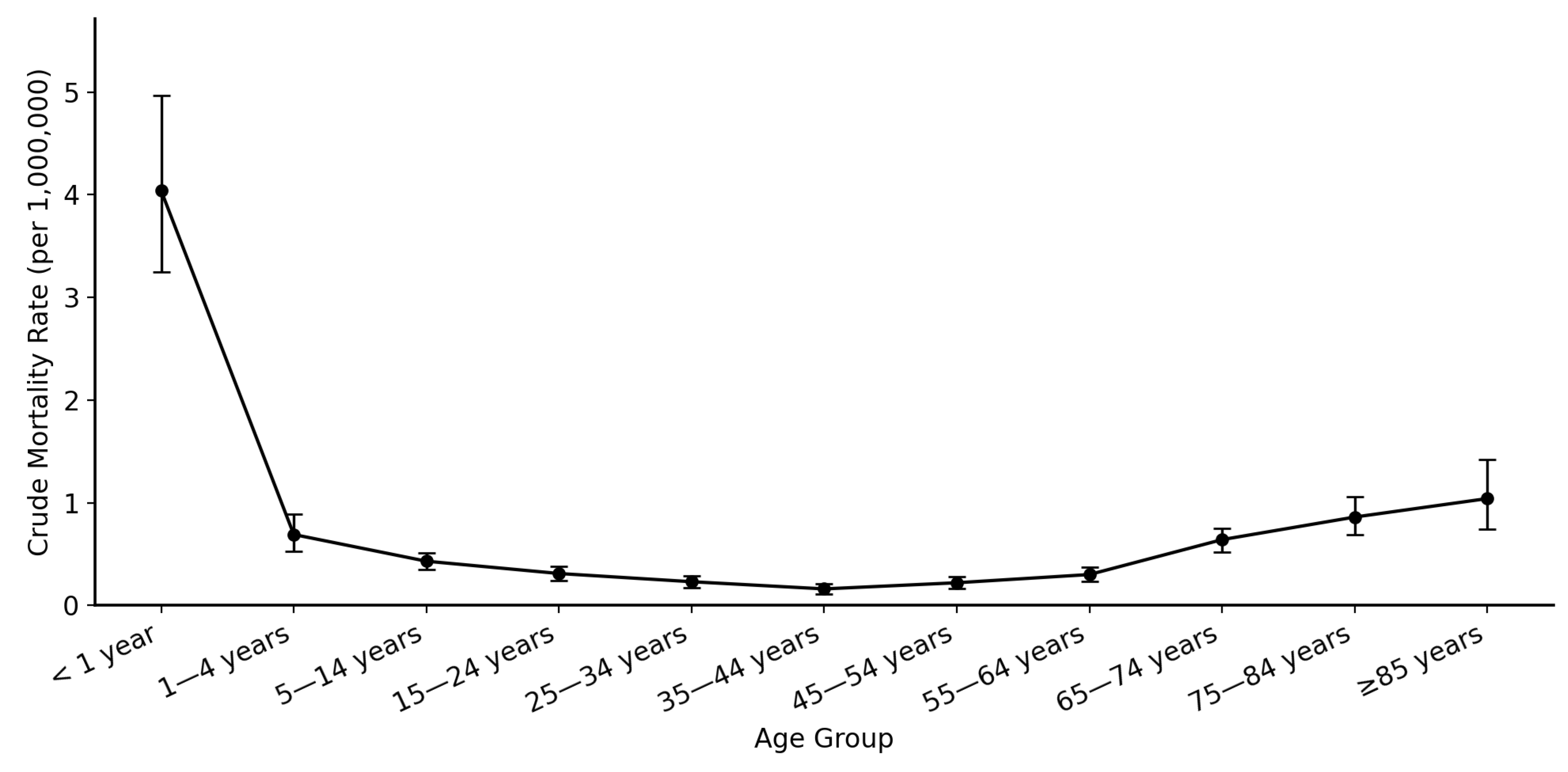

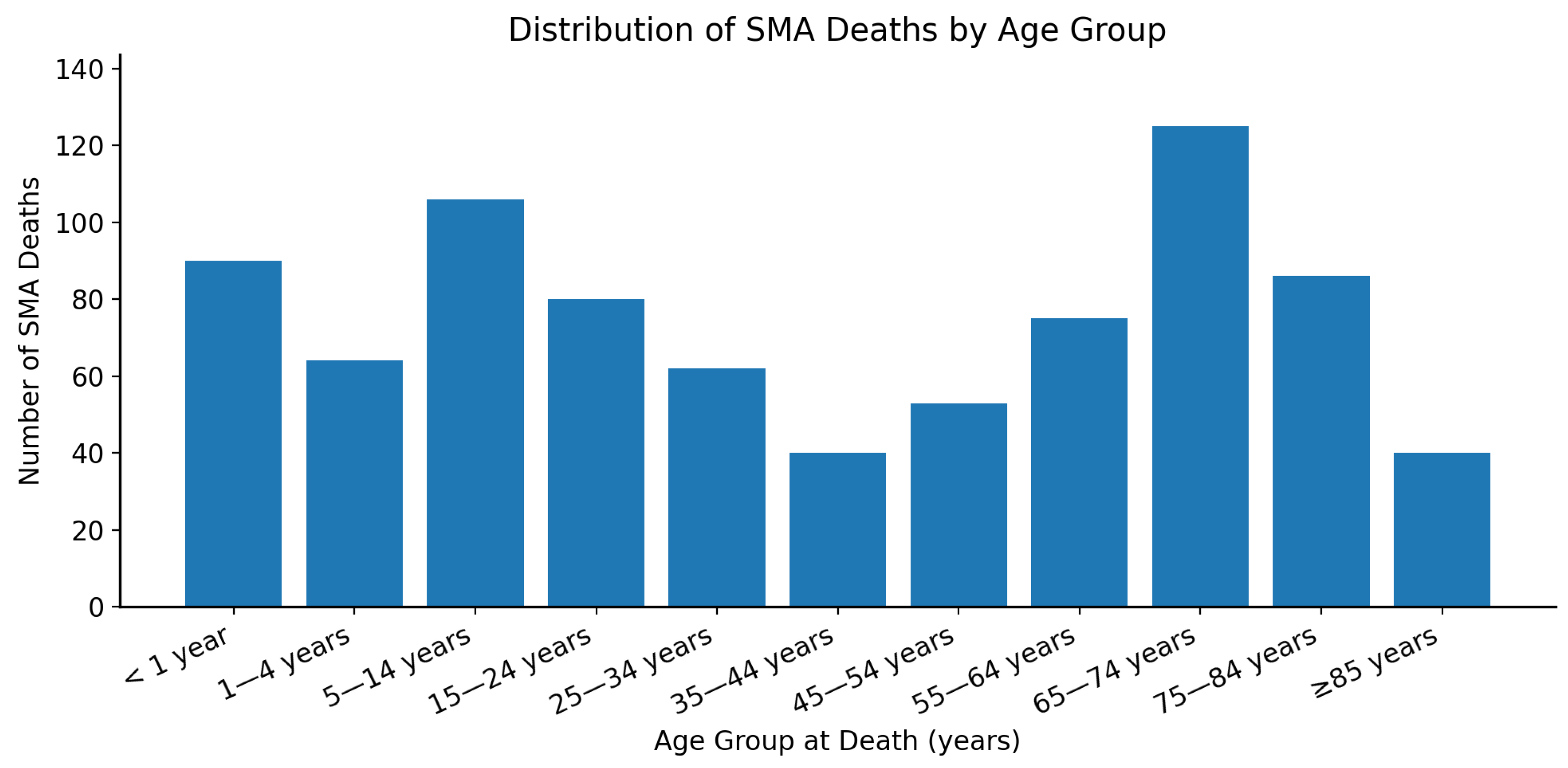

3.4. Age-Group Based Comparison

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mercuri, E.; Pera, M.C.; Scoto, M.; Finkel, R.; Muntoni, F. Spinal muscular atrophy—Insights and challenges in the treatment era. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2020, 16, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angilletta, I.; Ferrante, R.; Giansante, R.; Lombardi, L.; Babore, A.; Dell’Elice, A.; Alessandrelli, E.; Notarangelo, S.; Ranaudo, M.; Palmarini, C.; et al. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: An Evolving Scenario through New Perspectives in Diagnosis and Advances in Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lally, C.; Jones, C.; Farwell, W.; Reyna, S.P.; Cook, S.F.; Flanders, W.D. Indirect estimation of the prevalence of spinal muscular atrophy Type I, II, and III in the United States. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2016 Motor Neuron Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of motor neuron diseases 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishio, H.; Niba, E.T.E.; Saito, T.; Okamoto, K.; Takeshima, Y.; Awano, H. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: The Past, Present, and Future of Diagnosis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zeng, H.; Wei, Y.; Ma, X.; He, Z. An Overview of the Therapeutic Strategies for the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023, 34, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, C.J.J.; Tizzano, E.F.; Darras, B.T. Challenges and opportunities in spinal muscular atrophy therapeutics. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjartarson, H.T.; Nathorst-Böös, K.; Sejersen, T. Disease Modifying Therapies for the Management of Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (5q SMA): An Update on the Emerging Evidence. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, 16, 1865–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadman, R.I.; Bosboom, W.M.; van der Pol, W.L.; van den Berg, L.H.; Wokke, J.H.; Iannaccone, S.T.; Vrancken, A.F. Drug treatment for spinal muscular atrophy type I. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 4, CD006281, Update in Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 12, CD006281. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006281.pub5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.W.; Finkel, R.S.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Connolly, A.M.; Crawford, T.O.; Darras, B.T.; Iannaccone, S.T.; Kuntz, N.L.; Peña, L.D.M.; Shieh, P.B.; et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec gene therapy for symptomatic infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy in patients with two copies of SMN2 (STR1VE): An open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viscidi, E.; Juneja, M.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.; Li, L.; Farwell, W.; Bhan, I.; Makepeace, C.; Laird, K.; Kupelian, V.; et al. Comparative All-Cause Mortality Among a Large Population of Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy Versus Matched Controls. Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 449–457, Erratum in Neurol. Ther. 2022, 11, 929–930. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00357-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, K.D.; Murphy, S.L.; Xu, J.; Arias, E. Deaths: Final Data for 2020. Natl. Vital Stat. Rep. 2023, 72, 1–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, F.B.; Cisewski, J.A.; Xu, J.; Anderson, R.N. Provisional Mortality Data—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Ar Rochmah, M.; Shima, A.; Harahap, N.I.F.; Niba, E.T.E.; Morisada, N.; Yanagisawa, S.; Saito, T.; Kaneko, K.; Saito, K.; Morioka, I.; et al. Gender Effects on the Clinical Phenotype in Japanese Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2017, 63, E41–E44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zerres, K.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S. Natural history in proximal spinal muscular atrophy. Clinical analysis of 445 patients and suggestions for a modification of existing classifications. Arch Neurol. 1995, 52, 518–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipnick, S.L.; Agniel, D.M.; Aggarwal, R.; Makhortova, N.R.; Finlayson, S.G.; Brocato, A.; Palmer, N.; Darras, B.T.; Kohane, I.; Rubin, L.L. Systemic nature of spinal muscular atrophy revealed by studying insurance claims. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickson, B.C.; Donohoe, C.; Akmaev, V.R.; Sugarman, E.A.; Labrousse, P.; Boguslavskiy, L.; Flynn, K.; Rohlfs, E.M.; Walker, A.; Allitto, B. Differences in SMN1 allele frequencies among ethnic groups within North America. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 46, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarman, E.A.; Nagan, N.; Zhu, H.; Akmaev, V.R.; Zhou, Z.; Rohlfs, E.M.; Flynn, K.; Hendrickson, B.C.; Scholl, T.; Sirko-Osadsa, D.A. Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: Clinical laboratory analysis of >72,400 specimens. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 20, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, W.K.; Hamilton, D.; Kuhle, S. SMA carrier testing: A meta-analysis of differences in test performance by ethnic group. Prenat. Diagn. 2014, 34, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahungu, A.C.; Monnakgotla, N.; Nel, M.; Heckmann, J.M. A review of the genetic spectrum of hereditary spastic paraplegias, inherited neuropathies and spinal muscular atrophies in Africans. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaart, I.E.C.; Robertson, A.; Wilson, I.J.; Aartsma-Rus, A.; Cameron, S.; Jones, C.C.; Cook, S.F.; Lochmüller, H. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q-linked spinal muscular atrophy—A literature review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, V.J.; Puffenberger, E.G.; Bowser, L.E.; Brigatti, K.W.; Young, M.; Korulczyk, D.; Rodrigues, A.S.; Loeven, K.K.; Strauss, K.A. Spinal muscular atrophy within Amish and Mennonite populations: Ancestral haplotypes and natural history. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballreich, J.; Ezebilo, I.; Khalifa, B.A.; Choe, J.; Anderson, G. Coverage of genetic therapies for spinal muscular atrophy across fee-for-service Medicaid programs. J. Manag. Care Spéc. Pharm. 2022, 28, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Deng, S.; Chiriboga, C.A.; Kay, D.M.; Irumudomon, O.; Laureta, E.; Delfiner, L.; Treidler, S.O.; Anziska, Y.; Sakonju, A.; et al. Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in New York State: Clinical Outcomes from the First 3 Years. Neurology 2022, 99, e1527–e1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baker, M.; Griggs, R.; Byrne, B.; Connolly, A.M.; Finkel, R.; Grajkowska, L.; Haidet-Phillips, A.; Hagerty, L.; Ostrander, R.; Orlando, L.; et al. Maximizing the Benefit of Life-Saving Treatments for Pompe Disease, Spinal Muscular Atrophy, and Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Through Newborn Screening: Essential Steps. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Astudillo, C.; Byrne, B.J.; Salloum, R.G. Addressing the implementation gap in advanced therapeutics for spinal muscular atrophy in the era of newborn screening programs. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1064194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Deaths | AAMR per 1,000,000 | RR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 821 | 0.4 | NA | NA |

| Biological Sex | ||||

| Female (Ref) | 376 | 0.33 | 1 | NA |

| Male | 445 | 0.44 | 1.189 (1.035 to 1.366) | 0.014 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic (Ref) | 99 | 0.26 | 1 | NA |

| NH White | 574 | 0.47 | 1.808 (1.420 to 2.300) | <0.0001 |

| NH Black | 86 | 0.37 | 1.4230 (1.0438 to 1.9400) | 0.0257 |

| Asian | 36 | 0.36 | 1.3846 (0.9306 to 2.0600) | 0.1084 |

| Census Region | ||||

| Northeast (Ref) | 113 | 0.31 | 1 | NA |

| South | 289 | 0.37 | 1.1935 (0.9604 to 1.4831) | 0.1104 |

| Midwest | 191 | 0.44 | 1.4193 (1.1254 to 1.7900) | 0.003 |

| West | 228 | 0.49 | 1.5806 (1.2629 to 1.9783) | <0.0001 |

| Age Groups | Deaths | CMR per 1,000,000 | RR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 90 | 4.04 | 25.25 (18.30 to 34.83) | <0.000001 |

| 1–4 years | 64 | 0.69 | 4.31 (3.03 to 6.14) | <0.000001 |

| 5–14 years | 106 | 0.43 | 2.69 (1.98 to 3.65) | <0.000001 |

| 15–24 years | 80 | 0.31 | 1.94 (1.42 to 2.64) | <0.000001 |

| 25–34 years | 62 | 0.23 | 1.44 (1.01 to 2.05) | 0.045 |

| 35–44 years (Ref) | 40 | 0.16 | 1 | NA |

| 45–54 years | 53 | 0.22 | 1.38 (0.96 to 1.98) | 0.085 |

| 55–64 years | 75 | 0.3 | 1.88 (1.37 to 2.57) | <0.0001 |

| 65–74 years | 125 | 0.64 | 4 (2.94 to 5.43) | <0.000001 |

| 75–84 years | 86 | 0.86 | 5.38 (3.90 to 7.40) | <0.000001 |

| 85+ years | 40 | 1.04 | 6.50 (4.41 to 9.59) | <0.000001 |

| Total | 821 | 0.41 | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Al-Salahat, A.; Sharma, R. Disparities in Spinal Muscular Atrophy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2018–2023. NeuroSci 2026, 7, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010022

Al-Salahat A, Sharma R. Disparities in Spinal Muscular Atrophy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2018–2023. NeuroSci. 2026; 7(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Salahat, Ali, and Rohan Sharma. 2026. "Disparities in Spinal Muscular Atrophy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2018–2023" NeuroSci 7, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010022

APA StyleAl-Salahat, A., & Sharma, R. (2026). Disparities in Spinal Muscular Atrophy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2018–2023. NeuroSci, 7(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010022