Evolution of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Treatment: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Historical Perspective on Carpal Tunnel Treatment

3.1.1. Early Recognition and Initial Approaches

3.1.2. Formal Recognition and Early Surgical Management

3.1.3. Development of Surgical Techniques

3.1.4. Introduction of Conservative Treatments

- Wrist splinting: Rigid wrist splints are often worn at night to keep the wrist in a neutral position, thereby reducing pressure on the median nerve during sleep and alleviating nocturnal symptoms.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): Medications such as ibuprofen are used to manage pain and reduce inflammation in and around the carpal tunnel.

- Corticosteroid injections: Injecting a corticosteroid (a potent anti-inflammatory agent) directly into the carpal tunnel can provide temporary relief by diminishing swelling around the median nerve [14].

- Physical therapy: Therapeutic exercises and modalities have been incorporated to improve wrist and hand function. These include strength and flexibility exercises, nerve gliding techniques to enhance median nerve mobility, and ergonomic modifications to reduce strain on the wrist [15].

3.2. Evolution of Surgical Techniques

3.2.1. Open Carpal Tunnel Release

3.2.2. Mini-Open Carpal Tunnel Release

3.2.3. Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release

3.3. Comparative Studies and Outcomes

3.4. Advancements in Non-Surgical Management

3.4.1. Splinting and Bracing

3.4.2. Corticosteroid Injections

3.5. Physical Therapy and Ergonomic Modifications

3.6. Emerging Therapies and Future Directions

3.6.1. Ultrasound Therapy and Other Novel Treatments

3.6.2. Technological Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment

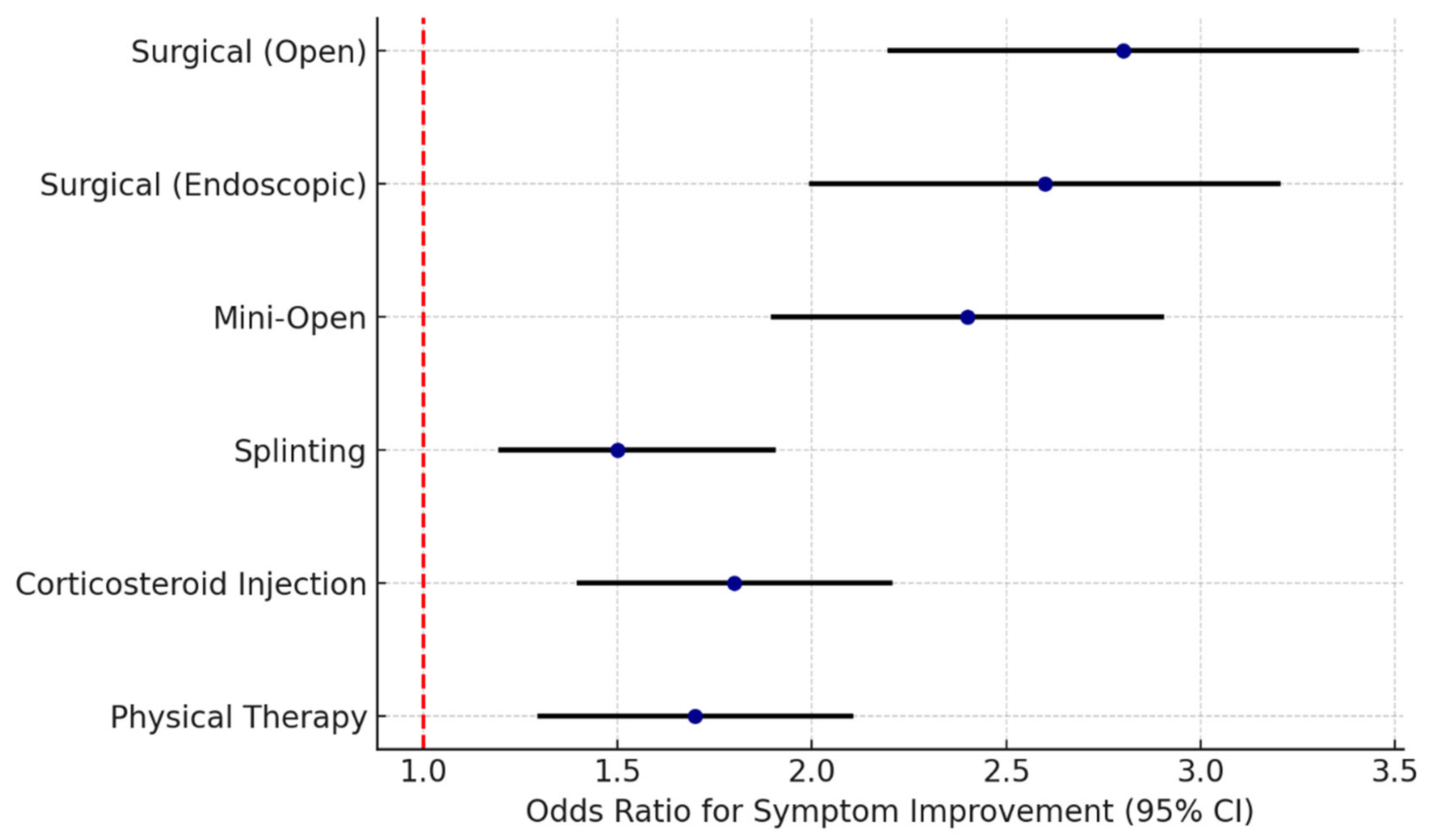

3.7. Comparative Analysis of Treatment Modalities

3.7.1. Efficacy of Surgical vs. Non-Surgical Interventions

3.7.2. Long-Term Outcomes and Recurrence Rates

3.7.3. Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life

3.8. Complications and Management Strategies

3.8.1. Surgical Complications and Their Management

- Infection: Though infrequent, post-surgical wound infections can occur. This risk is minimized by adhering to strict sterile techniques in the operating room and proper wound care after surgery. Minor infections can often be managed with oral antibiotics, whereas deeper infections may require intravenous antibiotics or, rarely, surgical drainage.

- Nerve injury: Intraoperative injury to the median nerve or its branches (such as recurrent motor branch of the median nerve, which innervates the thenar muscles) is a serious but rare complication. An injured nerve can lead to persistent numbness, loss of function, or neuropathic pain. Preventive measures include careful surgical technique and clear identification of anatomical landmarks; if an injury is recognized, nerve repair may be attempted.

- Hematoma formation: Bleeding at the surgical site can lead to a hematoma (a localized collection of blood) within the carpal tunnel or under the incision. Hematomas can cause swelling, pain, and potentially pressure on the nerve. Managing this may involve elevating the hand, applying ice, and sometimes returning to the operating room to evacuate the hematoma if it is large or compromising circulation.

- Scar tenderness: After an open carpal tunnel release, it is not uncommon for patients to experience tenderness or hypersensitivity at the scar on the palm. This usually improves over time. Management includes desensitization techniques (gentle massage, texture exposure), silicone gel pads, or steroid injections into the scar if the sensitivity is pronounced. Keeping the scar supple with massage and avoiding pressure on the heel of the hand during early recovery can help reduce scar discomfort.

3.8.2. Complications Related to Non-Surgical Treatments

- Corticosteroid injections: While often helpful for temporary relief, steroid injections can cause localized complications such as pain at the injection site, swelling, or even transient discoloration of the skin. In some cases, patients might experience a “cortisone flare” (an acute increase in pain due to crystallization of the steroid) for a day or two after the shot. Repeated injections carry a small risk of damage to structures within the carpal tunnel, and too-frequent steroid use can weaken nearby tendons or cause thinning of the skin and subcutaneous tissues.

- Extended splint use: Using a wrist splint continuously for long periods (beyond just night use or strategic daytime use) can lead to joint stiffness and reduced range of motion in the wrist. Muscular effects are also a concern—prolonged immobilization may result in weakening of the hand and forearm muscles and even atrophy from disuse [36]. It is important that patients balance rest with regular gentle movement exercises to keep the joints flexible and muscles conditioned.

- Over-aggressive physical therapy: While therapeutic exercises are usually beneficial, if they are performed incorrectly or too vigorously, they can exacerbate CTS symptoms. For example, overly strenuous wrist stretches or strengthening exercises performed in the midst of active nerve compression could increase inflammation or further irritate the median nerve. It is crucial that any exercise regimen for CTS be guided by a knowledgeable professional and tailored to the patient’s tolerance.

3.9. Strategies for Preventing Complications

- Meticulous surgical technique: For those undergoing carpal tunnel release, the surgeon’s skill and attention to detail are paramount. Identifying anatomical landmarks, using gentle tissue handling, and ensuring complete release of the transverse ligament while avoiding excessive dissection help prevent many surgical complications. Adhering strictly to sterile protocols also reduces infection risk.

- Patient selection and preoperative planning: Good outcomes begin with appropriate patient selection. Surgeons evaluate whether symptoms correlate with objective findings and confirm the diagnosis (often with nerve conduction studies) to ensure surgery is warranted. Any medical comorbidities (like coagulopathies or uncontrolled diabetes) are addressed preoperatively to decrease the risk of complications such as bleeding or poor wound healing.

- Postoperative care and rehabilitation: Effective pain management and guided rehabilitation after surgery can significantly influence recovery. Elevating the hand, using ice, and taking prescribed pain medications in the immediate postoperative period help control swelling and discomfort, potentially preventing complications like excessive scar adhesion or stiffness. Early mobilization of the fingers and thumb is encouraged while protecting the healing incision, to maintain tendon gliding and circulation. Structured hand therapy, when needed, can assist in scar management and restoring strength safely.

- Education for conservative management: When treating CTS non-surgically, educating patients is essential for complication prevention. Patients should understand how to properly wear and not overuse wrist splints, how to perform exercises with correct technique, and how to listen to their symptoms to avoid overexertion. Follow-up appointments are useful for reinforcing these points and for monitoring progress, ensuring that interventions are helping and not inadvertently causing harm.

- Use of established best practices: In navigating newer treatment options, it is often safest to rely on techniques and therapies with proven track records. For example, open carpal tunnel release is a well-established procedure with predictable outcomes and is often considered the gold standard against which newer techniques are measured [14]. By using validated methods (or adopting new ones only after sufficient evidence of safety and efficacy), clinicians can minimize unforeseen complications.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Summary of the Evolution of Carpal Tunnel Treatment

4.2. Future Directions in Carpal Tunnel Management

4.3. Current Best Practices

4.4. Future Research Needs and Opportunities

- Comparative effectiveness studies: Large-scale, long-term studies comparing surgical and non-surgical treatments (including newer interventions) are needed to determine which approaches yield the best outcomes for different patient subsets. These studies would inform guidelines on when to opt for surgery versus continued conservative care.

- Biomechanical insights: More research into the biomechanical and ergonomic factors that contribute to CTS could lead to improved preventive measures. Understanding how specific repetitive movements, wrist postures, or tool designs increase carpal tunnel pressure could drive the creation of better workplace ergonomics and protective equipment to reduce incidence.

- Predictors of treatment success: Investigations aimed at identifying which patient-specific factors (e.g., genetic markers, coexisting conditions, or imaging findings) predict a better response to certain treatments would enable personalized treatment plans. For instance, if certain imaging features predict poor response to splinting, those patients might be fast-tracked to surgery.

- Regenerative and biologic therapies: Emerging treatments like nerve wraps, stem cell injections, or gene therapy that encourage nerve healing and regeneration represent a frontier for severe cases of CTS, especially those with nerve damage. Research into these modalities, including controlled clinical trials, could open new avenues for restoring nerve function without mechanical decompression.

- Novel pharmacological approaches: There is an opportunity to explore medications that might prevent or reverse the pathologic changes in CTS. This could include drugs that reduce fibrosis in the carpal tunnel, improve microcirculation to the median nerve, or modulate inflammatory pathways more effectively and safely than current NSAIDs or steroids.

- Collaboration and data sharing: Establishing multicenter registries or databases for CTS treatment outcomes would greatly enhance the power of research. By pooling data from numerous clinics and hospitals, researchers could more rapidly identify trends, rare complications, or effective nuances in technique, thereby accelerating improvements in care. Such collaborative studies could also facilitate the development of consensus guidelines and standardized outcome measures for CTS research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTS | Carpal Tunnel Syndrome |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| PT | Physical Therapy |

| PRP | Platelet-Rich Plasma |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

References

- Ea, R. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Issues and answers. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 1995, 87, 369. [Google Scholar]

- Viera, A.J. Management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Am. Fam. Physician 2003, 68, 265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaparin, N.; Nguyen, D.; Gritsenko, K. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. In Pain Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; p. 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchino, G.; Pietramala, S.; Capece, G.; Arioli, L.; Greco, A.; Rocca, S.L.; Rocchi, L.; Fulchignoni, C. Is WALANT Really Necessary in Outpatient Surgery? J. Pers. Med. 2024, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchiyama, S.; Itsubo, T.; Nakamura, K.; Kato, H.; Yasutomi, T.; Momose, T. Current concepts of carpal tunnel syndrome: Pathophysiology, treatment, and evaluation. J. Orthop. Sci. 2010, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.S.; Siqueira, M.G. Conservative therapeutic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2017, 75, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzblau, A. What Is Carpal Tunnel Syndrome? JAMA 1999, 282, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, D.; Chhaya, S.K.; Morris, V. Carpal tunnel syndrome. Hosp. Med. 2002, 63, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi-Rad, M. A handy review of carpal tunnel syndrome: From anatomy to diagnosis and treatment. World J. Radiol. 2014, 6, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, H.; Read, J.A.; Kampa, R.; Hearnden, A.; Davey, P.A. Clinic-based nerve conduction studies reduce time to surgery and are cost effective: A comparison with formal electrophysiological testing. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2011, 93, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nancollas, M.; Peimer, C.A.; Wheeler, D.R.; Sherwin, F.S. Long-Term Results of Carpal Tunnel Release. J. Hand Surg. (Eur. Vol.) 1995, 20, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGurk, K.; Tracey, J.; Daley, D.; Daly, C.A. Diagnostic Considerations in Compressive Neuropathies. J. Hand Surg. Glob. Online 2022, 5, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrayes, M.S.; Altawili, M.A.; Alsaffar, M.H.; Alfarhan, G.Z.; Owedah, R.J.; Bodal, I.S.; Alshahrani, N.A.A.; Assiri, A.A.M.; Sindi, A.W. Surgical Interventions for the Management of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e55593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badger, S.A.; O’Donnell, M.E.; Sherigar, J.; Connolly, P.H.; Spence, R.A.J. Open carpal tunnel release—Still a safe and effective operation. Ulster. Med. J. 2008, 77, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carlson, H.L.; Colbert, A.P.; Frýdl, J.; Arnall, E.; Elliott, M.; Carlson, N.L. Current options for nonsurgical management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2010, 5, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Management of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. 18 May 2024. Available online: https://www.aaos.org/cts2cpg (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Kim, D. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Open Carpal Tunnel Release. J. Korean Neurotraumatol. Soc. 2008, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellman, H.; Kan, D.M.; Gee, V.; Kuschner, S.H.; Botte, M.J. Analysis of pinch and grip strength after carpal tunnel release. J. Hand Surg. 1989, 14, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzi, V.; Franzini, A.; Messina, G.; Broggi, G. Carpal tunnel syndrome: Matching minimally invasive surgical techniques. J. Neurosurg. 2008, 108, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.B.; Baratz, M.E. Limited Open Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Using the Safeguard System. Tech. Orthop. 2006, 21, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liawrungrueang, W.; Wongsiri, S. Effectiveness of Surgical Treatment in Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Mini-Incision Using MIS-CTS Kits: A Cadaveric Study. Adv. Orthop. 2020, 2020, 8278054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, V.; Marzano, F.; Placella, G. Update on surgical procedures for carpal tunnel syndrome: What is the current evidence and practice? What are the future research directions? World J. Orthop. 2023, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, D.; Goretti, C.; Tedeschi, R.; Boccolari, P.; Ricci, V.; Farì, G.; Vita, F.; Tarallo, L. Comparing endoscopic and conventional surgery techniques for carpal tunnel syndrome: A retrospective study. JPRAS Open. 2024, 41, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aleid, A.M.; Alanazi, S.N.; Aljabr, A.A.; Almalki, S.F.; AlAidarous, H.A.A.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Aleid, Z.M.; Alghamdi, Y.K.A.; Aldanyowi, S.N. A comparative meta-analysis of mini-transverse versus longitudinal techniques in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2024, 15, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ratnaparkhi, R.; Xiu, K.; Guo, X.; Li, Z. Changes in carpal tunnel compliance with incremental flexor retinaculum release. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2016, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Can, A.G.; Tezel, N. The effects of hand splinting in patients with early-stage thumb carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis: A randomized, controlled study. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazantzidou, V.; Lytras, D.; Kottaras, A.; Iakovidis, P.; Kottaras, I.; Chatziprodromidou, I.P. The efficacy of manual techniques in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms: A narrative review. Int. J. Orthop. Sci. 2021, 7, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, M.D.C.R. Evidence on Physiotherapeutic Treatment for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. J. Yoga Physiother. 2018, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqomi, I.T.; Widodo, A.; Ardi, Y.G. Penatalaksanaan Fisioterapi Pada Kasus Carpal Tunnel Syndrome di Klinik Fisioterapi Surabaya: Case Report. J. Innov. Res. Knowl. 2023, 3, 4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.J.; Karimi, H.; Ahmad, A.; Gillani, S.A.; Anwar, N.; Chaudhary, M.A. Comparative Efficacy of Routine Physical Therapy with and without Neuromobilization in the Treatment of Patients with Mild to Moderate Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 2155765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, S.; Naidich, T.P. The carpal tunnel: Ultrasound display of normal imaging anatomy and pathology. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2004, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaralieva, A.; Georgiev, G.P.; Karabinov, V.; Iliev, A.; Aleksiev, A. Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Approaches in Patients with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. Cureus 2020, 12, e7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michlovitz, S. Conservative Interventions for Carpal Tunnel Syndrome. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2004, 34, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeStefano, F.; Nordstrom, D.L.; Vierkant, R.A. Long-term symptom outcomes of carpal tunnel syndrome and its treatment. J. Hand Surg. 1997, 22, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaheer, S.A.; Ahmed, Z. Neurodynamic Techniques in the Treatment of Mild-to-Moderate Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, K.; Knudson, D. Change in Strength and Dexterity after Open Carpal Tunnel Release. Int. J. Sports Med. 2001, 22, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiew, F.; Florek, J.; Janowiec, S.; Florek, P. The use of orthoses in the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. A review of the literature from the last 10 years. Reumatol./Rheumatol. 2022, 60, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsiri, S.; Sarasombath, P.; Liawrungrueang, W. Minimally invasive carpal tunnel release: A clinical case study and surgical technique. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrell, N.T.; Harris, A.P.; Skjong, C.; Akelman, E. Carpal Tunnel Release: Do We Understand the Biomechanical Consequences? J. Wrist Surg. 2014, 3, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulenkamp, B.; Stacey, D.; Fergusson, D.; Hutton, B.; Mlis, R.S.; Graham, I.D. Protocol for treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures: A systematic review with network meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, P.S.; Du, A.L.; Gabriel, R.A.; Curran, B.P. Outcomes Following Distal Nerve Blocks for Open Carpal Tunnel Release: A Single-Institution Retrospective Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e41258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, T.J.; Dussik, C.M.; Clary, Z.; Hoffman, S.; Hammert, W.C.; Mahmood, B. Endoscopic Versus Open Carpal Tunnel Surgery: Risk Factors and Rates of Revision Surgery. J. Hand Surg. 2023, 48, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Technique | Incision Size | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open Carpal Tunnel Release | 3–5 cm | Direct visualization; high success rate | Larger scar; longer recovery |

| Mini-Open Release | 1.5–2 cm | Smaller incision; reduced tissue trauma | Less exposure; learning curve |

| Endoscopic Release | 1 cm (1 or 2 portals) | Minimal scarring; faster recovery; less pain | Steeper learning curve; risk of incomplete release or nerve injury |

| Conservative Modality | Mechanism | Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

| Wrist Splinting | Immobilizes wrist in neutral position to reduce median nerve pressure | Effective for mild cases; improves nocturnal symptoms |

| NSAIDs | Reduces pain and inflammation | Adjunctive symptom relief |

| Corticosteroid Injections | Reduces inflammation within carpal tunnel | Short-term relief (weeks/months) |

| Physical Therapy | Improves nerve mobility, strength, and ergonomics | Moderate short- to mid-term benefit; improves function |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Đilvesi, Đ.; Jelača, B.; Knežević, A.; Živanović, Ž.; Pantelić, V.; Golubović, J. Evolution of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Treatment: A Narrative Review. NeuroSci 2026, 7, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010010

Đilvesi Đ, Jelača B, Knežević A, Živanović Ž, Pantelić V, Golubović J. Evolution of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Treatment: A Narrative Review. NeuroSci. 2026; 7(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleĐilvesi, Đula, Bojan Jelača, Aleksandar Knežević, Željko Živanović, Veljko Pantelić, and Jagoš Golubović. 2026. "Evolution of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Treatment: A Narrative Review" NeuroSci 7, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010010

APA StyleĐilvesi, Đ., Jelača, B., Knežević, A., Živanović, Ž., Pantelić, V., & Golubović, J. (2026). Evolution of Carpal Tunnel Syndrome Treatment: A Narrative Review. NeuroSci, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci7010010