Relationship Between Brain Lesions in Patients with Post-Stroke Aphasia and Their Performance in Neuropsychological Language Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Neuropsychological Assessment

2.3. MRI Imaging and Data Analysis

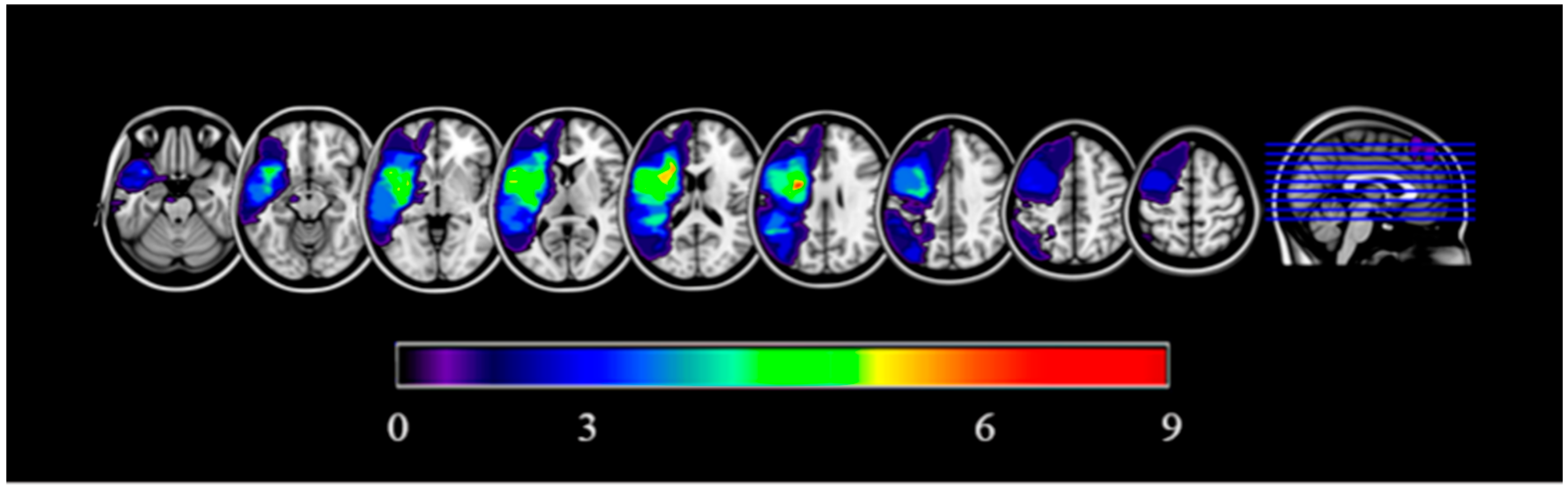

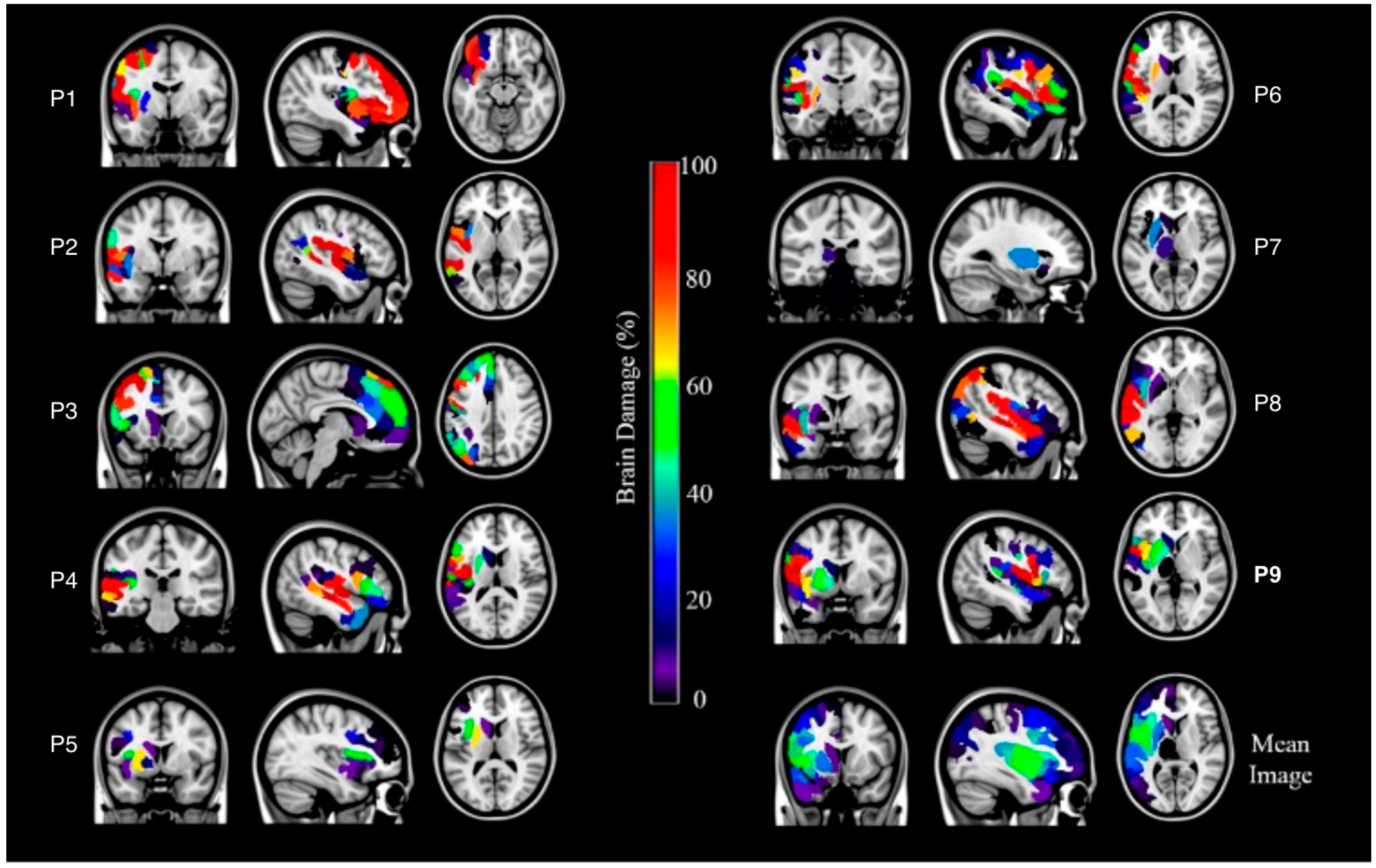

2.3.1. Lesion Data: Binary Lesion Maps Estimation

2.3.2. Gray Matter Lesion Load and White Matter Disconnections

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Grey Matter Lesion Load and White Matter Disconnection

3.2. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAL | Automated Anatomical Labeling |

| ACC | Anterior Cingulate Cortex |

| AF | Arcuate Fasciculus |

| AG | Angular Gyrus |

| ANTs | Advanced Normalization Tools |

| BDAE | Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination |

| CLSM | Connectome-based Lesion–Symptom Mapping |

| FG | Fusiform Gyrus |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| HCP | Human Connectome Project |

| IFG | Inferior Frontal Gyrus |

| IFO | Inferior Frontal Operculum |

| IFOF | Inferior Fronto-Occipital Fasciculus |

| ILF | Inferior Longitudinal Fasciculus |

| IPG | Inferior Parietal Gyrus |

| IPL | Inferior Parietal Lobule |

| LINDA | Lesion Identification with Neighborhood Data Analysis |

| MCC | Middle Cingulate Cortex |

| MFG | Middle Frontal Gyrus |

| MOG | Middle Occipital Gyrus |

| MPRAGE | Magnetization Prepared Rapid Acquisition Gradient Echo |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MTG | Middle Temporal Gyrus |

| OFC | Orbitofrontal Cortex |

| PostCG | Postcentral Gyrus |

| PreCG | Precentral Gyrus |

| PSA | Post-Stroke Aphasia |

| ROI | Region Of Interest |

| SFG | Superior Frontal Gyrus |

| SOG | Superior Occipital Gyrus |

| SPG | Superior Parietal Gyrus |

| STG | Superior Temporal Gyrus |

| VLSM | Voxel-based Lesion–Symptom Mapping |

References

- Berthier, M.L. Poststroke Aphasia. Drugs Aging 2005, 22, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, A. Las Afasias, 1st ed.; Universidad de Guadalajara: Jalisco, México, 2005; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.; Sacco, R.L.; Hacke, W.; Fisher, M.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P. World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022. Int. J. Stroke 2022, 17, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Blaha, M.J.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Das, S.R.; Deo, R.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Floyd, J.; Fornage, M.; Gillespie, C.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e146–e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthier, M.; Casares, N.G.; Dávila, G. Afasias y trastornos del habla. Med.-Programa Form. Médica Contin. Acreditado 2011, 10, 5035–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plowman, E.; Hentz, B.; Ellis, C. Post-stroke aphasia prognosis: A review of patient-related and stroke-related factors. J. Evaluation Clin. Pr. 2011, 18, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagata, S.A.; Yen, M.; McCarron, A.; Bautista, A.; Lamair-Orosco, G.; Wilson, S.M. Rapid recovery from aphasia after infarction of Wernicke’s area. Aphasiology 2016, 31, 951–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, P.M.; Vinter, K.; Olsen, T.S. Aphasia after Stroke: Type, Severity and Prognosis. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2003, 17, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menahemi-Falkov, M.; Breitenstein, C.; Pierce, J.E.; Hill, A.J.; O’HAlloran, R.; Rose, M.L. A systematic review of maintenance following intensive therapy programs in chronic post-stroke aphasia: Importance of individual response analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 44, 5811–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, J.-F.; Zhang, F.; Mirman, D. A data-driven approach to post-stroke aphasia classification and lesion-based prediction. Brain 2021, 144, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, M.P. Aphasia: Clinical and anatomic issues. In Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychology, 2nd ed.; Feinberg, T.E., Farah, M.J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Fridriksson, J.; Bonilha, L.; Rorden, C. Severe Broca’s aphasia without Broca’s area damage. Behav. Neurol. 2007, 18, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, I.; Regenbrecht, F.; Obrig, H. Lesion correlates of patholinguistic profiles in chronic aphasia: Comparisons of syndrome-, modality- and symptom-level assessment. Brain 2014, 137, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willmes, K.; Poeck, K. To what extent can aphasic syndromes be localized? Brain 1993, 116, 1527–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berthier, M.L. Unexpected brain-language relationships in aphasia: Evidence from transcortical sensory aphasia associated with frontal lobe lesions. Aphasiology 2001, 15, 99–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasselimis, D.S.; Simos, P.G.; Peppas, C.; Evdokimidis, I.; Potagas, C. The unbridged gap between clinical diagnosis and contemporary research on aphasia: A short discussion on the validity and clinical utility of taxonomic categories. Brain Lang. 2017, 164, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catani, M.; Mesulam, M. The arcuate fasciculus and the disconnection theme in language and aphasia: History and current state. Cortex 2008, 44, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catani, M.; Mesulam, M. What is a disconnection syndrome? Cortex 2008, 44, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, E.; Tononi, G. Diaschisis: Past, present, future. Brain 2014, 137, 2408–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleichgerrcht, E.; Kocher, M.; Nesland, T.; Rorden, C.; Fridriksson, J.; Bonilha, L. Preservation of structural brain network hubs is associated with less severe post-stroke aphasia. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2015, 34, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffis, J.C.; Metcalf, N.V.; Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Structural Disconnections Explain Brain Network Dysfunction after Stroke. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 2527–2540.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yourganov, G.; Fridriksson, J.; Rorden, C.; Gleichgerrcht, E.; Bonilha, L. Multivariate Connectome-Based Symptom Mapping in Post-Stroke Patients: Networks Supporting Language and Speech. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 6668–6679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilha, L.; Rorden, C.; Fridriksson, J. Assessing the Clinical Effect of Residual Cortical Disconnection After Ischemic Strokes. Stroke 2014, 45, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baboyan, V.; Basilakos, A.; Yourganov, G.; Rorden, C.; Bonilha, L.; Fridriksson, J.; Hickok, G. Isolating the white matter circuitry of the dorsal language stream: Connectome-Symptom Mapping in stroke induced aphasia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021, 42, 5689–5702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesbroek, J.M.; Lim, J.-S.; Weaver, N.A.; Arikan, G.; Kang, Y.; Kim, B.J.; Kuijf, H.J.; Postma, A.; Lee, B.-C.; Lee, K.-J.; et al. Anatomy of phonemic and semantic fluency: A lesion and disconnectome study in 1231 stroke patients. Cortex 2021, 143, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billot, A.; de Schotten, M.T.; Parrish, T.B.; Thompson, C.K.; Rapp, B.; Caplan, D.; Kiran, S. Structural disconnections associated with language impairments in chronic post-stroke aphasia using disconnectome maps. Cortex 2022, 155, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilha, L.; E Hillis, A.; Hickok, G.; Ouden, D.B.D.; Rorden, C.; Fridriksson, J. Temporal lobe networks supporting the comprehension of spoken words. Brain 2017, 140, 2370–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Gaizo, J.; Fridriksson, J.; Yourganov, G.; Hillis, A.E.; Hickok, G.; Misic, B.; Rorden, C.; Bonilha, L. Mapping Language Networks Using the Structural and Dynamic Brain Connectomes. Eneuro 2017, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridriksson, J.; Ouden, D.-B.D.; E Hillis, A.; Hickok, G.; Rorden, C.; Basilakos, A.; Yourganov, G.; Bonilha, L. Anatomy of aphasia revisited. Brain 2018, 141, 848–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, T.M.; Leff, A.P.; Price, C.J. Predicting language outcomes after stroke: Is structural disconnection a useful predictor? NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 19, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchin, W.; Ouden, D.-B.D.; Hickok, G.; E Hillis, A.; Bonilha, L.; Fridriksson, J. The Wernicke conundrum revisited: Evidence from connectome-based Lesion–Symptom mapping. Brain 2022, 145, 3916–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, N.; Rorden, C.; Fridriksson, J.; Desai, R.H. Canonical Sentence Processing and the Inferior Frontal Cortex: Is There a Connection? Neurobiol. Lang. 2022, 3, 318–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvonen, A.J.; Vadinova, V.; Garden, K.L.; Meinzer, M.; Roxbury, T.; O’Brien, K.; Copland, D.; McMahon, K.L.; Brownsett, S.L.E. Right hemispheric structural connectivity and poststroke language recovery. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 2897–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Prioris, M.J.; López-Barroso, D.; Roé-Vellvé, N.; Paredes-Pacheco, J.; Dávila, G.; Berthier, M.L. Repetitive verbal behaviors are not always harmful signs: Compensatory plasticity within the language network in aphasia. Brain Lang. 2019, 190, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Li, C.; Huang, Z.-G.; Zhao, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Wang, J. The longitudinal neural dynamics changes of whole brain connectome during natural recovery from poststroke aphasia. NeuroImage Clin. 2022, 36, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halai, A.D.; Woollams, A.M.; Ralph, M.A.L. Investigating the effect of changing parameters when building prediction models for post-stroke aphasia. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Barroso, D.; Paredes-Pacheco, J.; Torres-Prioris, M.J.; Dávila, G.; Berthier, M.L. Brain structural and functional correlates of the heterogenous progression of mixed transcortical aphasia. Anat. Embryol. 2023, 228, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souter, N.E.; Wang, X.; Thompson, H.; Krieger-Redwood, K.; Halai, A.D.; Ralph, M.A.L.; de Schotten, M.T.; Jefferies, E. Mapping lesion, structural disconnection, and functional disconnection to symptoms in semantic aphasia. Anat. Embryol. 2022, 227, 3043–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiebaut de Schotten, M.; Foulon, C.; Nachev, P. Brain disconnections link structural connectivity with function and behaviour. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Yao, D.; Liao, W.; Chen, H. Whole-brain functional connectome-based multivariate classification of post-stroke aphasia. Neurocomputing 2017, 269, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleichgerrcht, E.; Wilmskoetter, J.; Bonilha, L. Connectome-based Lesion–Symptom mapping using structural brain imaging. In Lesion-to-Symptom Mapping: Principles and Tools; Pustina, D., Mirman, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 180, pp. 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Elam, J.S.; Glasser, M.F.; Harms, M.P.; Sotiropoulos, S.N.; Andersson, J.L.; Burgess, G.C.; Curtiss, S.W.; Oostenveld, R.; Larson-Prior, L.J.; Schoffelen, J.-M.; et al. The Human Connectome Project: A retrospective. NeuroImage 2021, 244, 118543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeppel, D.; Hickok, G. Towards a new functional anatomy of language. Cognition 2004, 92, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, P.; Dick, A.S. Broca and Wernicke are dead, or moving past the classic model of language neurobiology. Brain Lang. 2016, 162, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickok, G.; Poeppel, D. Dorsal and ventral streams: A framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition 2004, 92, 67–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickok, G.; Poeppel, D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozari, N.; Dell, G.S. How damaged brains repeat words: A computational approach. Brain Lang. 2013, 126, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierpowska, J.; Gabarrós, A.; Fernández-Coello, A.; Camins, À.; Castañer, S.; Juncadella, M.; François, C.; Rodríguez-Fornells, A. White-matter pathways and semantic processing: Intrasurgical and Lesion–Symptom mapping evidence. NeuroImage Clin. 2019, 22, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kourtidou, E.; Kasselimis, D.; Angelopoulou, G.; Karavasilis, E.; Velonakis, G.; Kelekis, N.; Zalonis, I.; Evdokimidis, I.; Potagas, C.; Petrides, M. Specific disruption of the ventral anterior temporo-frontal network reveals key implications for language comprehension and cognition. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodglass, H.; Kaplan, E.; Weintraub, S. BDAE: The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Ambler, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.D. Mapping Symptoms to Brain Networks with the Human Connectome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoutio-Mazoyera, N.; Landeau, B.; Papathanassiou, D.; Crivello, F.; Etard, O.; Delcroix, N.; Tzourio-Mazoyer, B.; Joliot, M. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parcellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. NeuroImage 2002, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, B.T.; Krienen, F.M.; Sepulcre, J.; Sabuncu, M.R.; Lashkari, D.; Hollinshead, M.; Roffman, J.L.; Smoller, J.W.; Zöllei, L.; Polimeni, J.R.; et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 2011, 106, 1125–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustina, D.; Coslett, H.B.; Turkeltaub, P.E.; Tustison, N.; Schwartz, M.F.; Avants, B. Automated segmentation of chronic stroke lesions using LINDA: Lesion identification with neighborhood data analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2016, 37, 1405–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.L.; Kim, H.; Liew, S. A comparison of automated lesion segmentation approaches for chronic stroke T1-weighted MRI data. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 4669–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avants, B.B.; Tustison, N.J.; Song, G.; Cook, P.A.; Klein, A.; Gee, J.C. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. NeuroImage 2011, 54, 2033–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tustison, N.J.; Avants, B.B. Explicit B-spline regularization in diffeomorphic image registration. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffis, J.C.; Metcalf, N.V.; Corbetta, M.; Shulman, G.L. Lesion Quantification Toolkit: A MATLAB software tool for estimating grey matter damage and white matter disconnections in patients with focal brain lesions. NeuroImage Clin. 2021, 30, 102639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthier, M.L.; Ralph, M.A.L.; Pujol, J.; Green, C. Arcuate fasciculus variability and repetition: The left sometimes can be right. Cortex 2012, 48, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geschwind, N. Disconnexion Syndromes in Animals and Man. Brain 1965, 88, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartha, L.; Benke, T. Acute conduction aphasia: An analysis of 20 cases. Brain Lang. 2003, 85, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal, B.; Ardila, A. The role of the arcuate fasciculus in conduction aphasia. Brain 2009, 132, 2309–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, S.; van der Zwaag, W.; Marques, J.P.; Frackowiak, R.S.J.; Clarke, S.; Saenz, M. Human Primary Auditory Cortex Follows the Shape of Heschl’s Gyrus. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 14067–14075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, T.A. Information flow in the auditory cortical network. Hear. Res. 2011, 271, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickok, G.; Buchsbaum, B.; Humphries, C.; Muftuler, T. Auditory–Motor Interaction Revealed by fMRI: Speech, Music, and Working Memory in Area Spt. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2003, 15, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchsbaum, B.R.; Baldo, J.; Okada, K.; Berman, K.F.; Dronkers, N.; D’esposito, M.; Hickok, G. Conduction aphasia, sensory-motor integration, and phonological short-term memory—An aggregate analysis of lesion and fMRI data. Brain Lang. 2011, 119, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Kim, Y.W.; Nam, H.S.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, D.Y. Neural Substrates of Aphasia in Acute Left Hemispheric Stroke Using Voxel-Based Lesion-symptom Brain Mapping. Brain Neurorehabilit. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridriksson, J.; Kjartansson, O.; Morgan, P.S.; Hjaltason, H.; Magnusdottir, S.; Bonilha, L.; Rorden, C. Impaired Speech Repetition and Left Parietal Lobe Damage. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 11057–11061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, J.V.; Katseff, S.; Dronkers, N.F. Brain regions underlying repetition and auditory-verbal short-term memory deficits in aphasia: Evidence from voxel-based Lesion–Symptom mapping. Aphasiology 2012, 26, 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogalsky, C.; Poppa, T.; Chen, K.-H.; Anderson, S.W.; Damasio, H.; Love, T.; Hickok, G. Speech repetition as a window on the neurobiology of auditory–motor integration for speech: A voxel-based Lesion–Symptom mapping study. Neuropsychologia 2015, 71, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripamonti, E.; Frustaci, M.; Zonca, G.; Aggujaro, S.; Molteni, F.; Luzzatti, C. Disentangling phonological and articulatory processing: A neuroanatomical study in aphasia. Neuropsychologia 2018, 121, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sul, B.; Lee, K.B.; Hong, B.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.; Hwang, W.S.; Lim, S.H. Association of Lesion Location With Long-Term Recovery in Post-stroke Aphasia and Language Deficits. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Døli, H.; Helland, W.A.; Helland, T.; Specht, K. Associations between lesion size, lesion location and aphasia in acute stroke. Aphasiology 2020, 35, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geranmayeh, F.; Brownsett, S.L.E.; Wise, R.J.S. Task-induced brain activity in aphasic stroke patients: What is driving recovery? Brain 2014, 137, 2632–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almairac, F.; Herbet, G.; Moritz-Gasser, S.; de Champfleur, N.M.; Duffau, H. The left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus subserves language semantics: A multilevel lesion study. Anat. Embryol. 2014, 220, 1983–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, M.V.; Isaev, D.Y.; Dragoy, O.V.; Akinina, Y.S.; Petrushevskiy, A.G.; Fedina, O.N.; Shklovsky, V.M.; Dronkers, N.F. Diffusion-tensor imaging of major white matter tracts and their role in language processing in aphasia. Cortex 2016, 85, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Barroso, D.; de Diego-Balaguer, R.; Cunillera, T.; Camara, E.; Münte, T.F.; Rodriguez-Fornells, A. Language Learning under Working Memory Constraints Correlates with Microstructural Differences in the Ventral Language Pathway. Cereb. Cortex 2011, 21, 2742–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Barroso, D.; de Diego-Balaguer, R. Language Learning Variability within the Dorsal and Ventral Streams as a Cue for Compensatory Mechanisms in Aphasia Recovery. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.F.; Raygor, K.P.; Berger, M.S. Contemporary model of language organization: An overview for neurosurgeons. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 122, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catani, M.; Jones, D.K.; Donato, R.; Ffytche, D.H. Occipito-temporal connections in the human brain. Brain 2003, 126, 2093–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catani, M.; Thiebautdeschotten, M. A diffusion tensor imaging tractography atlas for virtual in vivo dissections. Cortex 2008, 44, 1105–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saur, D.; Kreher, B.W.; Schnell, S.; Kümmerer, D.; Kellmeyer, P.; Vry, M.-S.; Umarova, R.; Musso, M.; Glauche, V.; Abel, S.; et al. Ventral and dorsal pathways for language. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18035–18040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandonnet, E.; Nouet, A.; Gatignol, P.; Capelle, L.; Duffau, H. Does the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus play a role in language? A brain stimulation study. Brain 2007, 130, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J.; Rowley, J.; Chowdhury, R.; Jolicoeur, P.; Klein, D.; Grova, C.; Rosa-Neto, P.; Kobayashi, E. Inferior Longitudinal Fasciculus’ Role in Visual Processing and Language Comprehension: A Combined MEG-DTI Study. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, C.; Sarubbo, S.; Jovicich, J. A Missing Connection: A Review of the Macrostructural Anatomy and Tractography of the Acoustic Radiation. Front. Neuroanat. 2019, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, H.; Guo, L.; Li, K.; Li, L.; Zhang, S.; Shen, D.; Hu, X.; Liu, T. Characterization of U-shape streamline fibers: Methods and applications. Med. Image Anal. 2014, 18, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, L.; Velásquez, C.; Porrero, J.A.G.; de Lucas, E.M.; Martino, J. Heschl’s gyrus fiber intersection area: A new insight on the connectivity of the auditory-language hub. Neurosurg. Focus 2020, 48, E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, A.; Zahn, R.; Najera, O.I.; Martin, R.C. Semantic Working Memory Predicts Sentence Comprehension Performance: A Case Series Approach. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 887586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient | Age (in Years) | Sex | Years of Education | Aphasia Type | Lesion Site (Left Hemisphere) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | Male | 20 | Anomic | IFG, MFG, SFG, OFC, IFO, PreCG, PostCG, insula, rolandic operculum, caudate, putamen |

| 2 | 40 | Female | 14 | Conduction | PreCG, PostCG, rolandic operculum, IFO, insula, IPL, AG, supramarginal and Heschl’s gyri, STG and MTG |

| 3 | 79 | Female | 12 | Global | FG, MFG, SFG, OFC, precuneus, IFO, rolandic operculum, PreCG, PostCG, insula, ACC, MCC, SOG, MOG, SPG, IPG, AG, MTG and caudate |

| 4 | 46 | Male | 24 | Mixed transcortical | FG, inferior OFC, IFO, PreCG, PostCG, rolandic operculum, insula, Heschl’s gyrus, STG, MTG, caudate, putamen and pallidum |

| 5 | 77 | Male | 23 | Transcortical sensory | MFG, IFG, IFO, insula, caudate, putamen, pallidum |

| 6 | 71 | Female | 14 | Global | MFG, IFG, inferior OFC, IFO, rolandic operculum, PreCG, PostCG, insula, IPL, supramarginal, angular and Heschl’s gyri, caudate, putamen and pallidum |

| 7 | 53 | Female | 20 | Anomic | OFC, olfactory, insula, putamen, pallidus and thalamus |

| 8 | 51 | Male | 14 | Mixed transcortical | Rolandic operculum, insula, MOG, PostCG, SPG, IPG, supramarginal, angular and Heschl’s giry, STG, MTG and putamen |

| 9 | 73 | Male | 12 | Mixed transcortical | MFG, IFG, IFO, PreCG, PostCG, rolandic operculum, insula, Heschl’s gyrus, STG, caudate, putamen and pallidum |

| Category/Subtest | Patients | Group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| SEVERITY | 90 | 80 | 0 | 40 | 90 | 0 | 100 | 40 | 40 | 53.3 |

| FLUENCY | 100 | 80 | 0 | 7 | 100 | 0 | 85 | 52 | 20 | 49.3 |

| Sentence length | 100 | 100 | 0 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 30 | 20 | 51.1 |

| Melodic line | 100 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 25 | 20 | 42.8 |

| Grammatical form | 100 | 100 | 0 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 70 | 100 | 20 | 55.6 |

| CONVERSATION | 85 | 85 | 10 | 50 | 85 | 0 | 90 | 50 | 65 | 57.8 |

| Simple social responses | 100 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 20 | 50 | 65.6 |

| Complexity index | 75 | 53 | 16 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 80 | 35 | 80 | 45.4 |

| ORAL COMPREHENSION | 47 | 60 | 7 | 38 | 30 | 16 | 85 | 5 | 48 | 37.3 |

| Word discrimination | 50 | 70 | 0 | 70 | 20 | 30 | 70 | 12 | 40 | 40.2 |

| Commands | 60 | 60 | 10 | 30 | 50 | 8 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 46.8 |

| Complex material | 30 | 50 | 10 | 26 | 20 | 10 | 85 | 0 | 5 | 26.2 |

| ARTICULATION | 53 | 33 | 30 | 39 | 65 | 5 | 67 | 39 | 57 | 43.2 |

| Non-verbal agility | 30 | 30 | 50 | 70 | 15 | 15 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 42.2 |

| Verbal agility | 30 | 40 | 10 | 18 | 80 | 0 | 50 | 18 | 80 | 36.2 |

| Articulatory agility | 100 | 30 | 30 | 40 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 40 | 30 | 52.2 |

| RECITATION | 93 | 83 | 25 | 38 | 83 | 35 | 100 | 30 | 60 | 60.5 |

| Automated sequences | 70 | 70 | 20 | 10 | 70 | 0 | 100 | 18 | 50 | 45.3 |

| Recitation | 100 | 60 | 60 | 30 | 100 | 30 | 100 | 30 | 100 | 67.8 |

| Melody | 100 | 100 | 10 | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 10 | 30 | 62.2 |

| Rhythm | 100 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 60 | 10 | 100 | 60 | 60 | 66.7 |

| REPETITION | 85 | 30 | 75 | 27 | 100 | 11 | 100 | 13 | 33 | 52.5 |

| Words | 70 | 20 | 100 | 18 | 100 | 12 | 100 | 15 | 30 | 51.7 |

| Sentences | 100 | 40 | 50 | 35 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 10 | 35 | 53.3 |

| NAMING | 63 | 73 | 20 | 14 | 50 | 0 | 87 | 17 | 38 | 40.2 |

| Naming response | 80 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 80 | 28 | 28 | 46.2 |

| Boston Naming Test | 70 | 80 | 20 | 25 | 50 | 0 | 80 | 12 | 65 | 44.7 |

| Category naming | 40 | 40 | 10 | 15 | 30 | 0 | 100 | 10 | 20 | 29.4 |

| PARAPHASIA | 86 | 72 | 15 | 35 | 64 | 38 | 80 | 66 | 71 | 58.6 |

| Speech assessment | 100 | 50 | 20 | 25 | 70 | 0 | 75 | 70 | 35 | 49.4 |

| Phonemic | 60 | 30 | 10 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 80 | 40 | 80 | 48.9 |

| Verbal | 70 | 80 | 5 | 70 | 40 | 90 | 45 | 80 | 40 | 57.8 |

| Neologistic | 100 | 100 | 30 | 30 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 72.2 |

| Multiple words | 100 | 100 | 30 | 30 | 10 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 |

| READING | 77 | 83 | 2 | 59 | 75 | 12 | 94 | 26 | 3 | 47.9 |

| Writing matching | 100 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 100 | 40 | 100 | 40 | 5 | 66.1 |

| Number matching | 40 | 100 | 0 | 40 | 100 | 15 | 100 | 20 | 5 | 46.7 |

| Picture-word matching | 20 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 18 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 5 | 42.8 |

| Lexical decisión | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 10 | 5 | 59.4 |

| Word recognition | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 0 | 10 | 58.9 |

| Morphemes | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 56.1 |

| Word reading | 100 | 60 | 0 | 30 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 32 | 0 | 46.9 |

| Sentence reading | 50 | 40 | 0 | 20 | 70 | 10 | 100 | 30 | 0 | 35.6 |

| Sentence comprehension | 100 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 50 | 0 | 35.6 |

| Paragraph comprehension | 60 | 80 | 0 | 15 | 40 | 0 | 80 | 15 | 0 | 32.2 |

| WRITING | 65 | 88 | 0 | 62 | 86 | 9 | 64 | 26 | 0 | 44.3 |

| Mechanics | 10 | 100 | 0 | 40 | 100 | 0 | 5 | 45 | 0 | 33.3 |

| Letter selection | 80 | 30 | 0 | 50 | 80 | 0 | 50 | 5 | 0 | 32.8 |

| Motor skills | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 0 | 60.0 |

| Basic vocabulary | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 5 | 0 | 56.1 |

| Regular phonetics | 40 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 0 | 53.3 |

| Common irreg. words | 50 | 100 | 0 | 60 | 70 | 20 | 100 | 20 | 0 | 46.7 |

| Written picture naming | 60 | 70 | 0 | 45 | 70 | 10 | 60 | 10 | 0 | 36.1 |

| Narrative writing | 80 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 36.1 |

| Language Production | 80 | 90 | 10 | 19 | 75 | 0 | 65 | 56 | 43 | 48.6 |

| Language Comprehension | 47 | 60 | 7 | 38 | 30 | 17 | 85 | 5 | 48 | 37.4 |

| Language Competence | 63 | 75 | 8 | 29 | 53 | 8 | 75 | 31 | 45 | 43.0 |

| Brain Damage | Patients | Group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Brain Networks (Left Hemisphere) | ||||||||||

| Ventral Attentional (Temporoparietal junction, ventral frontal cortex) | 32.23 (44.61) | 27.47 (38.70) | 14.02 (25.09) | 39.80 (48.49) | 5.29 (14.71) | 44.07 (45.62) | 0.03 (0.11) | 28.28 (40.02) | 23.80 (37.04) | 23.89 (14.89) |

| Somatomotor (Precentral cortex (primary motor area), postcentral cortex (primary somatosensory area), auditory-related regions in the temporal lobe) | 12.09 (27.45) | 30.04 (43.74) | 12.38 (24.24) | 16.13 (32.78) | 0.00 (0.01) | 26.61 (37.77) | 0 (0) | 19.45 (36.02) | 16.50 (29.04) | 14.80 (10.30) |

| Default Mode Network (Medial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus) | 14.49 (32.27) | 16.05 (33.36) | 25.74 (35.05) | 15.71 (31.51) | 0 (0) | 7.54 (19.95) | 0.01 (0.04) | 26.07 (41.22) | 1.02 (5.34) | 11.85 (10.32) |

| Control (Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, lateral parietal regions) | 35.54 (46.47) | 2.07 (7.72) | 14.37 (28.21) | 4.48 (20.41) | 1.99 (5.51) | 14.95 (31.77) | 0.11 (0.51) | 11.37 (19.67) | 2.41 (6.28) | 9.70 (11.24) |

| Dorsal Attentional (Intraparietal sulcus, frontal eye fields) | 19.16 (36.79) | 0.75 (3.14) | 26.17 (41.13) | 0.09 (0.42) | 0.14 (0.68) | 9.49 (26.86) | 0 (0) | 7.59 (24.41) | 4.03 (17.01) | 7.49 (9.43) |

| Limbic (Orbitofrontal cortex, anterior temporal áreas) | 1.81 (5.65) | 0 (0) | 0.40 (1.39) | 6.93 (14.16) | 0 (0) | 1.21 (2.84) | 0 (0) | 2.27 (5.72) | 0.42 (1.31) | 1.45 (2.22) |

| Visual (Occipital cortex, primary and secondary visual areas, occipital lobe regions) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.98 (4.12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.52 (5.80) | 0 (0) | 0.28 (0.57) |

| Left Subcortical Areas | ||||||||||

| Pallidum (Lenticular nucleus) | 24.8 | 0.39 | 0.1 | 46.35 | 64.1 | 68.53 | 33.9 | 5.05 | 53.2 | 32.94 (26.95) |

| Thalamus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.42 | 15.97 | 21.76 | 2.26 | 0.04 | 43.39 | 9.43 (15.08) |

| Putamen (Lenticular nucleus) | 1.26 | 0 | 4.58 | 13.55 | 6.07 | 4.59 | 2.25 | 0 | 13.94 | 5.14 (5.31) |

| Caudate nucleus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0 | 9.01 | 0 | 0.07 | 1.02 (3.00) |

| Cerebellum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 (0.00) |

| Brainstem | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.48 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 (0.16) |

| White Matter Tracts (Left Hemisphere) | Patients | Group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Association Pathways | ||||||||||

| Arcuate Fasciculus (AF) | 100 | 70.36 | 100 | 100 | 83.42 | 100 | 95.04 | 100 | 100 | 94.31 (10.53) |

| Inferior Fronto Occipital Fasciculus (IFOF) | 98.62 | 92.69 | 51.76 | 100 | 99.34 | 100 | 98.24 | 97.82 | 79.72 | 90.91 (16.04) |

| Extreme Capsule (EMC) | 92.63 | 92.63 | 60.66 | 100 | 45.49 | 100 | 68.57 | 100 | 100 | 84.44 (20.73) |

| Middle Longitudinal Fasciculus (MdLF) | 44.90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 71.66 (44.45) |

| Frontal Aslant Tract (AST) | 100 | 0 | 100 | 99.71 | 95.90 | 100 | 24.20 | 11.96 | 98.31 | 70.01 (43.91) |

| Superior Longitudinal Fasciculus (SLF) | 89.39 | 14.99 | 94.38 | 54.26 | 28.03 | 95.81 | 47.22 | 33.03 | 77.92 | 59.45 (30.86) |

| U-fibers (U) | 29.92 | 31.27 | 70.99 | 41.15 | 17.89 | 69.14 | 3.72 | 48.34 | 50.20 | 40.29 (22.27) |

| Inferior Longitudinal Fasciculus (ILF) | 3.00 | 68.34 | 26.27 | 75.39 | 0 | 79.40 | 0 | 69.12 | 34.19 | 39.52 (34.00) |

| Uncinate Fasciculus (UF) | 62.50 | 1.44 | 0 | 94.15 | 19.06 | 92.54 | 22.75 | 36.60 | 23.56 | 39.18 (35.88) |

| Cingulum (C) | 4.87 | 0 | 80.90 | 0 | 0.95 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9.64 (26.77) |

| Vertical Occipital Fasciculus (VOF) | 0 | 0 | 19.74 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0 | 2.21 (6.58) |

| Commisural Pathways | ||||||||||

| Anterior Commisure (AC) | 58.90 | 30.37 | 0.61 | 98.96 | 92.00 | 99.06 | 93.79 | 33.47 | 98.96 | 67.35 (37.67) |

| Corpus Callosum MidAnterior (CCMidAnterior) | 83.62 | 0.98 | 99.89 | 38.74 | 72.00 | 44.31 | 6.01 | 4.96 | 42.39 | 43.66 (35.92) |

| Corpus Callosum Central (CCCentral) | 65.69 | 0.41 | 88.69 | 53.01 | 7.39 | 51.79 | 75.97 | 0 | 47.91 | 43.43 (33.20) |

| Corpus Callosum Posterior (CCPosterior) | 0.74 | 45.87 | 61.82 | 42.15 | 0.42 | 61.89 | 0.49 | 64.75 | 46.98 | 36.12 (27.82) |

| Corpus Callosum Anterior (CCAnterior) | 60.01 | 0 | 85.32 | 18.31 | 59.27 | 23.32 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 2.88 | 27.71 (32.34) |

| Corpus Callosum MidPosterior (CCMidPost) | 3.03 | 0.22 | 16.82 | 21.76 | 0 | 19.85 | 63.52 | 1.12 | 23.56 | 16.65 (20.17) |

| Posterior Commisure (PC) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Projection Pathways | ||||||||||

| Frontopontine Tract (FPT) | 91.77 | 0 | 99.92 | 99.92 | 91.19 | 100 | 94.81 | 0 | 99.84 | 75.27 (42.82) |

| Acoustic Radiation (AR) | 0 | 97.78 | 81.31 | 91.12 | 0 | 100 | 16.07 | 100 | 96.31 | 64.73 (45.13) |

| Corticospinal Tract (CST) | 52.22 | 2.02 | 76.82 | 95.33 | 32.63 | 100 | 100 | 5.50 | 95.61 | 62.24 (40.46) |

| Corticostriatal Pathway (CS) | 79.36 | 13.83 | 79.87 | 74.84 | 81.82 | 80.38 | 61.79 | 15.27 | 63.64 | 61.20 (27.43) |

| Corticothalamic Pathway (CT) | 46.32 | 11.80 | 74.75 | 54.59 | 41.65 | 88.51 | 30.86 | 33.66 | 61.41 | 49.28 (23.50) |

| Temporopontine Tract (TPT) | 0 | 28.45 | 99.14 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 99.14 | 100 | 15.52 | 49.14 (48.70) |

| Occipitopontine Tract (OPT) | 0 | 15.59 | 91.31 | 14.48 | 0 | 100 | 82.85 | 96.44 | 40.31 | 49.00 (43.26) |

| Parietopontine Tract (PPT) | 0.35 | 5.85 | 30.63 | 74.17 | 0 | 98.25 | 97.82 | 23.82 | 75.65 | 45.17 (41.27) |

| Optic Radiation (OR) | 0 | 8.57 | 37.55 | 6.12 | 0 | 94.29 | 1.22 | 88.57 | 0 | 26.26 (38.21) |

| Fornix (F) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Cerebellum | ||||||||||

| Superior Cerebellar Peduncle (SCP) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18.52 | 0 | 19.66 | 0 | 0 | 4.24 (8.42) |

| Middle Cerebellar Peduncle (MCP) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Cerebellum (CB) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Inferior Cerebellar Peduncle (ICP) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Vermis (V) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Brainstem | ||||||||||

| Medial Lemniscus (ML) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 79.61 | 0 | 0 | 8.85 (26.54) |

| Spinothalamic Tract (STT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 47.69 | 0 | 0 | 5.30 (15.90) |

| Central Tegmental Tract (CTT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Dorsal Longitudinal Fasciculus (DLF) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Lateral Lemniscus (LL) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus (MLF) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Rubrospinal Tract (RST) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Castillo, J.; Rivas-Fernández, M.Á.; Varela-López, B.; Cid-Fernández, S.; Galdo-Álvarez, S. Relationship Between Brain Lesions in Patients with Post-Stroke Aphasia and Their Performance in Neuropsychological Language Assessment. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040122

Romero-Castillo J, Rivas-Fernández MÁ, Varela-López B, Cid-Fernández S, Galdo-Álvarez S. Relationship Between Brain Lesions in Patients with Post-Stroke Aphasia and Their Performance in Neuropsychological Language Assessment. NeuroSci. 2025; 6(4):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040122

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Castillo, Jorge, Miguel Ángel Rivas-Fernández, Benxamín Varela-López, Susana Cid-Fernández, and Santiago Galdo-Álvarez. 2025. "Relationship Between Brain Lesions in Patients with Post-Stroke Aphasia and Their Performance in Neuropsychological Language Assessment" NeuroSci 6, no. 4: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040122

APA StyleRomero-Castillo, J., Rivas-Fernández, M. Á., Varela-López, B., Cid-Fernández, S., & Galdo-Álvarez, S. (2025). Relationship Between Brain Lesions in Patients with Post-Stroke Aphasia and Their Performance in Neuropsychological Language Assessment. NeuroSci, 6(4), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurosci6040122