Rethinking Coastal Areas Through Youth Perceptions and the Coastality Gap Index: A Case Study of the Island of Mallorca

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Coastality as a Framework for Understanding Symbolic Connections to the Ocean

1.2. Contextual Focus: The Case of Mallorca

1.3. The Coastality Gap Index: A Tool for Measuring Spatial-Symbolic Disconnect

1.4. Research Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Context

2.2. Instruments

- b1. Self-identification of territoriality and personal information: this section was designed to explore how students perceive their place of residence in relation to the coast. Students were asked to indicate their gender, municipality of residence, and whether they considered it to be coastal or inland. They also provided information about their current grade level and school name.

- b2. Symbolic representation: These questions draw on established methodologies in tourism research, particularly the use of image-based preference tests to explore affective and motivational responses to landscapes [56]. These techniques aim to reveal the symbolic meanings and emotional associations that individuals attach to different environments, offering insights into how people perceive, idealize, or identify with landscape types. Students were shown a series of standardized images and asked two questions. First, they were asked to choose the image they liked the most. Second, they were asked to indicate in which landscape they would prefer to live. All images were generated using artificial intelligence to deliberately avoid depicting specific, recognizable locations in Mallorca. This approach was chosen to ensure neutrality, preventing students from being influenced by personal familiarity or associations with particular towns.

- b3. Emotional connection to the marine environment: Students reported their emotional responses toward the sea, choosing among a list of positive, neutral and negative feelings.

- b4. Experiential interaction: Students described the frequency of their visits to the coast and the activities they engaged in (e.g., leisure, fishing, or sport-related practices).

- b5. Communication and information sources: Students identified their main sources of communication and information about the sea (family, friends, school, internet, books, television).

- b6. Marine knowledge indicators: Two dimensions of marine knowledge were assessed.

- General OL was evaluated through students’ self-perceived knowledge, their level of agreement with key OL principles, and their perceptions of human–ocean interactions. This approach focused on subjective understandings aligned with the OL Framework, rather than factual recall, to capture how students internalize and relate to marine concepts.

- Local marine knowledge was measured through the recognition of culturally and environmentally significant elements of the Mallorcan marine environment. These included Posidonia oceanica (a key seagrass species), the traditional fishing boat (llaüt), and common fish species such as Coryphaena hippurus (llampuga) and Pagellus erythrinus (pagell). Other indicators of place-based familiarity included terms like embat (local sea breeze), rissaga (meteotsunami), albufera (coastal lagoon), and species of ecological importance such as the endangered bivalve nacra (Pinna nobilis). Additionally, elements of maritime craftsmanship, such as the role of the mestre d’aixa (master boatbuilder), and traditional small boats like the batel, were used to capture deeper layers of local marine heritage.

- The final version of the questionnaire is provided in the Appendix A.

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

- (a)

- Descriptive and comparative analysis

- The distribution of objective versus perceived coastality,

- Potential mismatches between physical proximity and symbolic identification,

- Differences by municipality and school center.

- (b)

- Spatial Analysis: Coastality Gap Index

- Distance to Coastline: A Euclidean distance raster was generated from the official coastline of Mallorca using a 250 m resolution. The values were normalized to a 0–1 scale, with 1 representing the point farthest from the sea on the island.

- Symbolic Inlandness: For each populated nucleus with survey data, the percentage of students who identified their municipality as “inland” was calculated and rasterised using the same 1 km grid.

- Index Formula: The Coastality Gap Index was derived by subtracting the normalized distance from the symbolic inlandness value:

- CGIi = Coastality Gap Index for location i (dimensionless, range: −1 to +1)

- P.inlandi = Proportion of students in location i who self-identify as “inland” (range: 0 to 1, where 0 = all students identify as coastal, 1 = all identify as inland)

- D.normi = Normalized Euclidean distance from location i to the nearest coastline (range: 0 to 1, where 0 = at the coast, 1 = maximum inland distance on the island, approximately 25 km).

- Positive values indicate areas where inland identification exceeds expectations based on distance.

- Negative values represent zones where students feel coastal despite being relatively inland.

- Values near zero suggest symbolic–spatial alignment.

- 4.

- Classification Thresholds and Justification: The CGI was grouped into three interpretative zones:

- Symbolically coastal (Gap Index < −0.05)

- Spatial-symbolic alignment (−0.05 to +0.20)

- Inland identification gap (>+0.20)

- (c)

- Cluster analysis

3. Results

3.1. Visual Exploration of Real vs. Perceived Coastality

3.1.1. Coastal-Inland Divide

3.1.2. Symbolic Landscape Preferences: Image and Place Identity

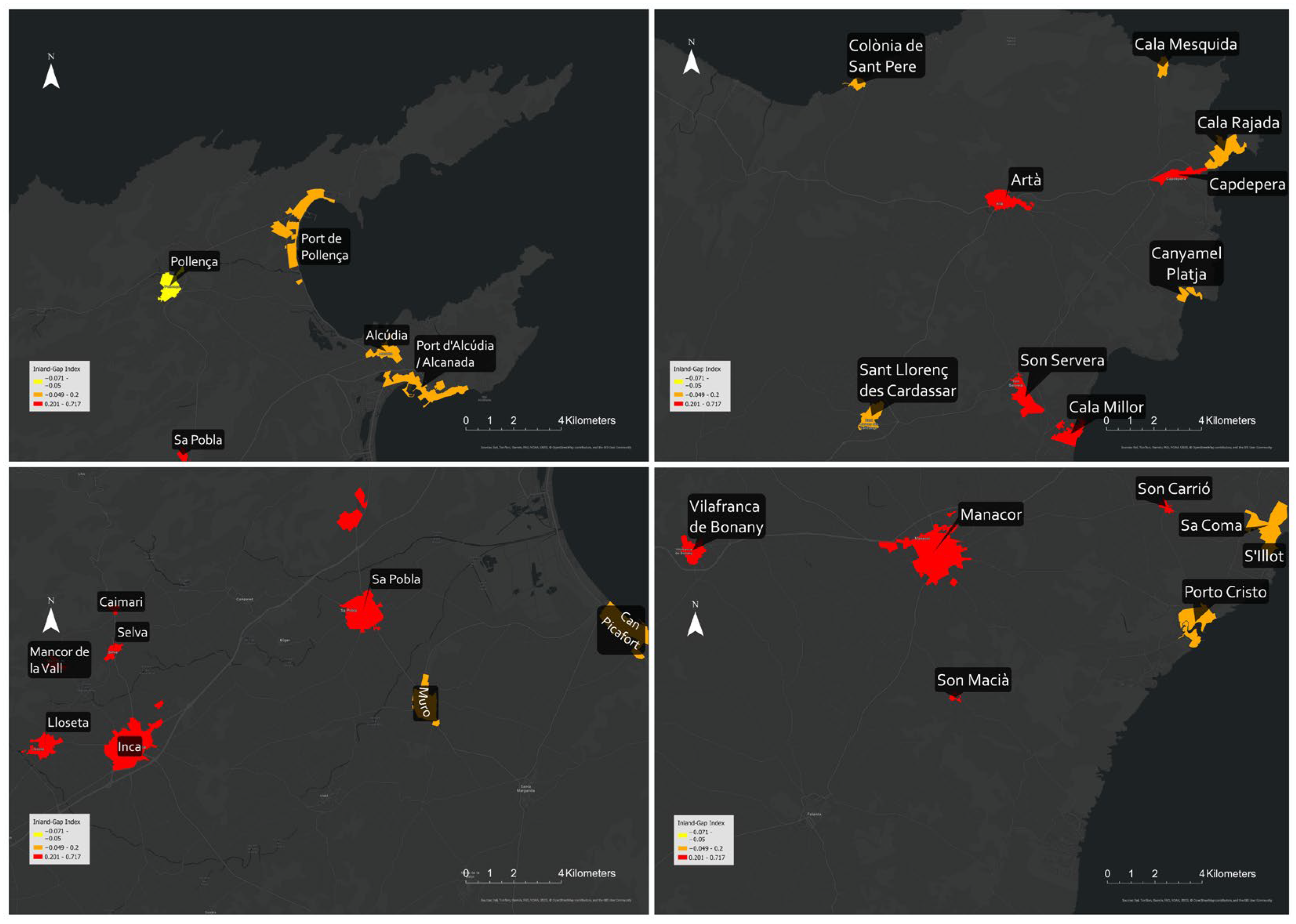

3.2. Results of the Index Gap

- Symbolically coastal (Index < −0.05): This category includes only Pollença (−0.07) where students expressed a strong symbolic attachment to the ocean despite moderate inland distances. These cases suggest that local culture, traditions, or family engagement with the sea may shape symbolic identity more strongly than geography.

- Symbolic–geographic alignment (−0.05 to +0.20): The majority of centers fell into this zone, showing consistency between perceived inlandness and actual distance to the coast. Examples include port areas such as Portocolom (0.00), Port de Pollença (0.00) and Cala Rajada (0.09), and presents interesting results in Muro (0.17) and Sant Llorenç (0.15). These locations typically lie within 11 km of the coastline and show moderate levels of inland self-identification.

- Coastality gap zone (Index > +0.20): This group reveals a notable divergence between physical proximity and symbolic perception. Despite being only 6–10 km from the coast, students in centers such as Son Macià (0.72), Sa Pobla (0.67) and Son Carrió (0.64), reported high rates of inland self-identification. The highest value, found in Son Macià, suggests a symbolic detachment from the marine environment even in relatively accessible coastal areas.

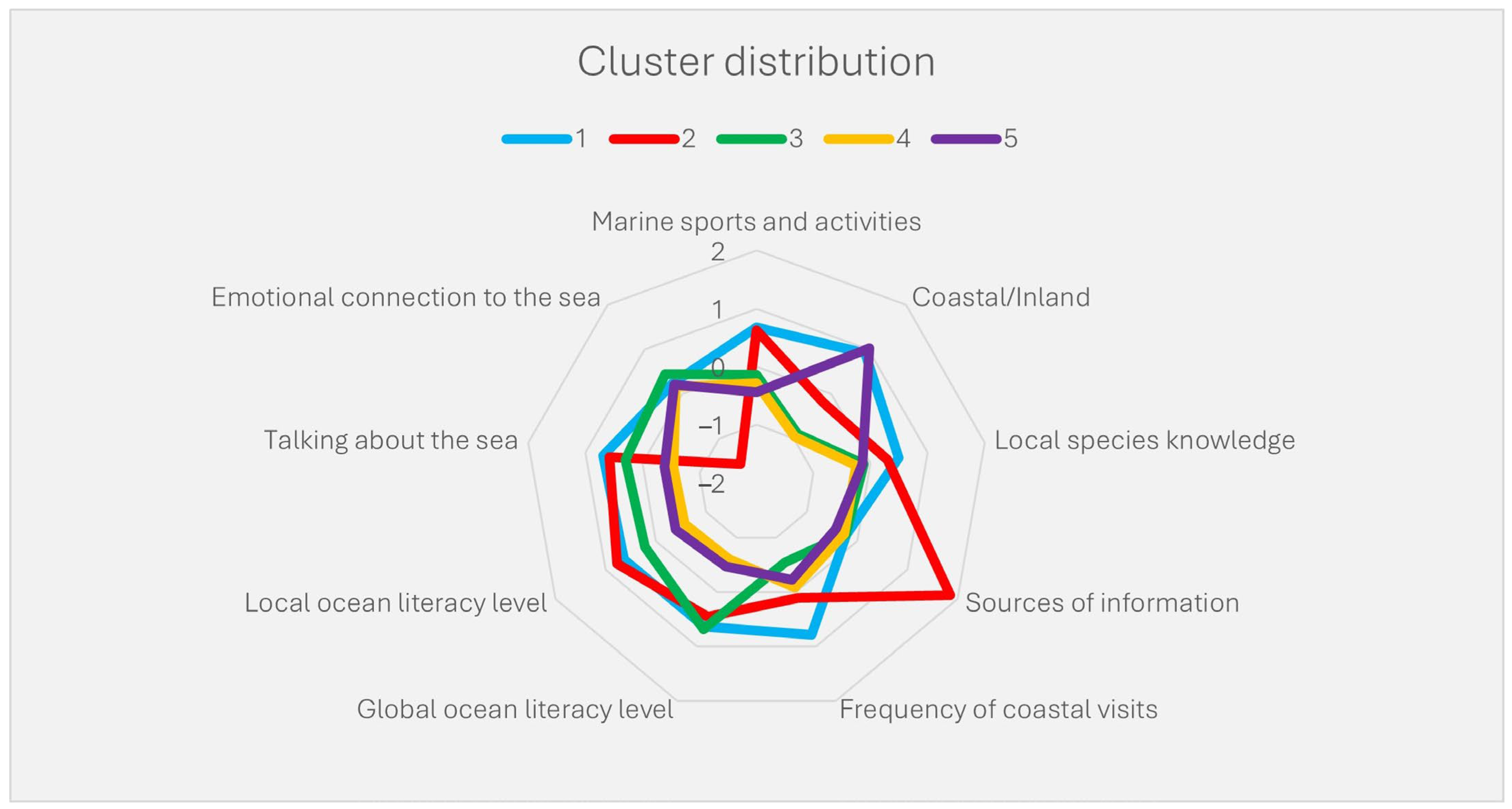

3.3. Clustering

- Cluster 1—Connected Coastal Engagers: This group represents students who self-identify as coastal (0.92) and exhibit strong integration of marine experience and knowledge. They frequently visit the sea (0.78), engage in marine sports (0.67), and demonstrate high global (0.63) and local (0.63) OL. They actively talk about the sea (0.68), express a positive emotional connection (0.24), and have above-average knowledge of local marine species (0.48). This profile reflects a balanced and well-developed marine identity.

- Cluster 2—Informed but Emotionally Disconnected: These students tend to perceive their environment as inland (−0.20) but demonstrate high local OL (0.77) and moderate global OL (0.45). Despite marine sports engagement (0.63) and low frequency of sea visits (0.11), they access a wide range of information sources (1.85) and frequently talk about the sea (0.57). However, their emotional connection is strongly negative (−1.57), pointing to a disconnect between knowledge and emotional experience.

- Cluster 3—Curious Distant Observers: Students in this cluster perceive their municipality as more inland (−0.89) and report low frequency of coastal visits (−0.54). They engage little in marine sports (−0.13) and have limited species knowledge (−0.12). Despite these limitations, they show moderately high global OL (0.68), but only low local OL (0.21). Their emotional connection is slightly positive (0.44), and their conversations about the sea are infrequent (0.29). This group demonstrates cognitive potential but remains physically and socially distant from the sea.

- Cluster 4—Disconnected and Unaware: These students strongly perceive their region as inland (−0.96) and exhibit the lowest scores in nearly every dimension. They rarely visit the sea (−0.07), do not engage in marine sports (−0.28), and show low global (−0.60) and local (−0.57) OL. Knowledge of species is minimal (−0.26), discussions about the sea are rare (−0.54), and they consult very few sources (−0.25). Their emotional connection is neutral (0.1613), reinforcing a general detachment.

- Cluster 5—Passive Coastal Residents: This group perceives their municipality as coastal (1.03) but shows low levels of marine activity and knowledge. Their participation in marine sports is low (−0.44), sea visits are infrequent (−0.22), and they show limited global (−0.45) and local (−0.39) OL. They rarely discuss marine topics (−0.38), use few information sources (−0.41), and their emotional connection is only slightly positive (0.20). Their perceived coastal identity is not reflected in active engagement.

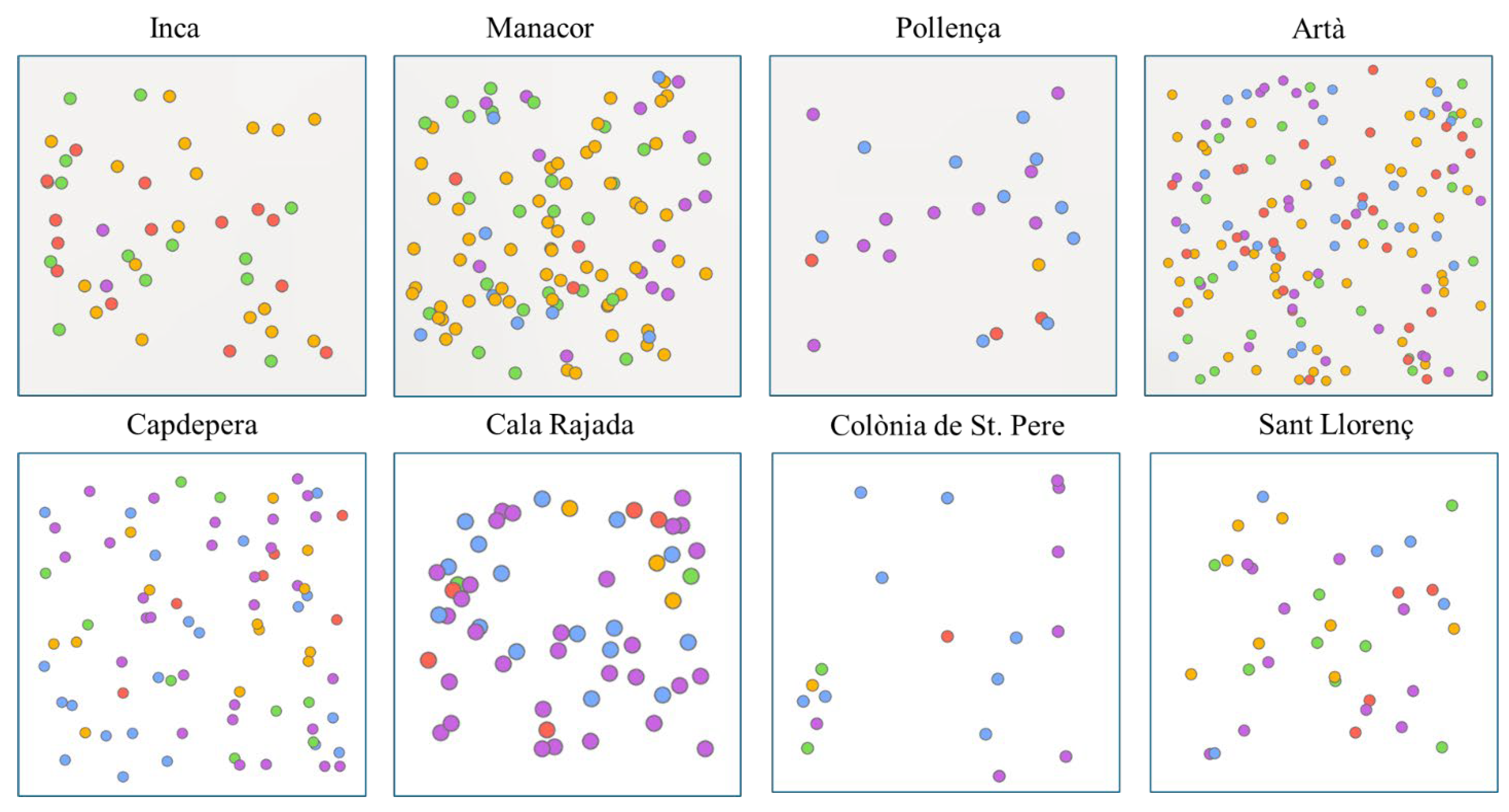

- Pollença stands out as the clearest example of active coastal engagement, with most students falling into Cluster 1 (Connected Coastal Engagers) and Cluster 5 (Passive Coastal Residents). This distribution reflects a population that predominantly identifies as coastal, where a significant portion not only lives near the sea but also integrates marine experiences, sports, and knowledge into their identity. The presence of Cluster 5 suggests that while coastal identity is strong, it does not always translate into active participation. A similar duality appears in Cala Rajada, Capdepera, and Colònia de Sant Pere. These municipalities show a dominant presence of Cluster 5, indicating students who perceive themselves as coastal but lack strong emotional connection, knowledge, or regular engagement with the sea. Cluster 1 also appears in each of these locations, though to a lesser extent than in Pollença, suggesting that while some students are actively involved, the broader trend is one of passive affiliation with the marine environment. This pattern points to a coastal but disengaged identity, where proximity to the sea does not necessarily foster deeper involvement.

- Artà and Manacor share a different profile: one of diverse and fragmented engagement. Both municipalities display a wide distribution across all five clusters, with no single dominant group. In Artà, Cluster 4 (Disconnected and Unaware) is the most prevalent, while Clusters 1, 2, and 3 also have strong representation. Manacor shows a similar spread, with moderate presence across Clusters 2, 3, 4, and 5. This distribution indicates communities where students’ relationships with the sea are highly variable, some informed, others curious but distant, and many with low awareness or connection, reflecting internal heterogeneity in marine identity and literacy.

- Inca and Sant Llorenç des Cardessar represent a third group, characterized by inland-informed but emotionally disconnected profiles. In both cases, Cluster 1 is nearly absent, while Clusters 2 (Informed but Emotionally Disconnected), 3 (Curious Distant Observers), and 4 dominate. Students in these areas may access information about the sea and demonstrate some cognitive understanding especially global and local OL, but lack direct experiences, emotional resonance, or regular interaction with marine environments. These patterns reflect a geographic and symbolic distance from the sea, where knowledge exists in the absence of personal or cultural connection.

4. Discussion

4.1. Symbolic Detachment in Geographically Coastal Areas

4.2. Youth Profiles Show Diverse Relationships with the Sea

4.3. Territorial Patterns and Local Contrasts

4.4. Implications for Educational and Policy Strategies

4.5. Methodological Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

- Scientific contributions

- New indicator: The CGI provides a measurable way to detect divergences between geographical location and symbolic identification with the sea.

- New typology: The five-cluster model introduces perceptual categories that move beyond binary coastal/inland distinctions.

- New integration: The combination of spatial analysis with perceptual profiling offers a scalable method for linking subjective identity to territorial patterns.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OL | Ocean Literacy |

| CGI | Coastality Gap Index |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| EEZ | Exclusive Economic Zone |

| UNCLOS | United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea |

| SDG(s) | Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

| OLP | Ocean Literacy Principles (si lo mencionas explícitamente) |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| EU | European Union |

| VET | Vocational Education and Training |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| LOPDGDD | Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos y Garantía de los Derechos Digitales |

| HE | Higher Education |

Appendix A

- 1.

- Gender☐ Female☐ Male☐ Non-binary☐ Prefer not to say

- 2.

- Municipality (town/city) where you live:____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 3.

- Would you describe your area as…☐ Coastal☐ Inland

- 4.

- What grade are you in?☐ 5th Primary☐ 6th Primary☐ 1st ESO☐ 2nd ESO☐ 3rd ESO☐ 4th ESO☐ Other: ________________________________

- 5.

- Which school do you attend? _________________________________

- 6.

- Write the first three words that come to mind when you think of the sea:____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- 7.

- Which image do you like the most? (see images on the table)A ☐ B ☐ C ☐

- 8.

- Which of the following towns in Mallorca would you choose to live in?A ☐ B ☐ C ☐

- 9.

- How would you rate your knowledge about the following?(Mark with a cross: 1 = I know almost nothing, 5 = I know a lot)

- The ocean: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Climate change: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Marine conservation: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Currents and winds: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Dune systems: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Ecosystem services: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Eutrophication: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Freshwater systems: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- The Balearic Sea: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Marine biodiversity: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Marine pollution: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Blue carbon: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Carbon sinks: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- One Health: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Blue economy: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Streams: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- 10.

- Do you know the following words?☐ Llaüt☐ Embat☐ Albufera☐ Mestre d’aixa☐ Posidonia☐ Rissaga☐ Batel☐ Llampuga☐ Nacra☐ Pagell

- 11.

- Read the following statements and indicate your level of agreement:(1 = disagree, 2 = neutral, 3 = agree)

- The Earth has a large ocean with varied characteristics. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- The ocean and its life shape the Earth’s properties. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- The ocean has a strong influence on weather and climate. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- The ocean made Earth habitable. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- The ocean supports high biodiversity and ecosystems. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- The ocean and humanity are inextricably connected. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- The ocean remains largely unexplored. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- Protecting the ocean requires studying and understanding it. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- The sea influences my life. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- My daily actions affect the sea, even if I live inland. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- If everyone made small changes to help the ocean/environment, it would have global effects. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- I miss the sea when I haven’t been there for a long time. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- There is a special place for me on the coast or at sea. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- I enjoy going to coastal areas/the sea. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- In general, people do not know enough about marine ecosystems in Mallorca. ☐1 ☐2 ☐3

- 12.

- What do you usually feel when you go to the sea? (Select up to 5)☐ Worry☐ Wonder☐ Curiosity☐ Calm/Relaxation☐ Happiness☐ Joy☐ Shame☐ Anger☐ Anxiety☐ Motivation☐ Guilt☐ Fear☐ Enthusiasm☐ Surprise☐ Fulfillment☐ Boredom☐ Sadness☐ Insecurity☐ Confidence☐ Confusion☐ Loneliness☐ Indifference☐ Inspiration☐ Connection with nature☐ Connection with myself☐ Other: ___________________

- 13.

- How often do you visit the sea or coastal areas in Mallorca?☐ Every day☐ Once a week☐ Every 15 days☐ Once a month☐ During holidays (especially summer)☐ Weekends in general☐ Weekends and holidays☐ Almost never☐ Never

- 14.

- Can you name at least five marine species you can see on the coasts of Mallorca?(Avoid generic names like “fish”; if unsure, give as much detail as possible.)1. __________ 2. __________ 3. __________ 4. __________ 5. __________

- 15.

- If you need to look up information about the sea, which source would you prefer?☐ Books and magazines☐ Internet search☐ Social media☐ Documentaries and films☐ Personal experience☐ Ask experts☐ Ask family or teachers☐ Talks and workshops☐ Other: _____________________________

- 16.

- Do you usually talk about the sea with other people? If yes, with whom?☐ Family☐ Friends☐ Teachers☐ Neighbors☐ I don’t usually talk about the sea☐ I post on social media☐ Other: _____________________________

- 17.

- Do you practice any sea-related sport? If yes, which?☐ Snorkeling☐ Swimming☐ Surf/Windsurf☐ Paddleboarding☐ Kayaking☐ Rowing☐ Sailing☐ Scuba diving☐ I do not practice sea sports☐ Other: _____________________________

- 18.

- What other activities do you usually do at the sea/beach? (e.g., photography, family picnic, etc.)________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

- Duration: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Materials used: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Explanations: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Interesting: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Surprising: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Boring: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Repetitive: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Useful for learning new things: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Would recommend it: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- There are forests in the sea. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- There are many similarities between marine and terrestrial forests. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Most marine forests are composed of animals. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- There is so much life in underwater darkness. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Corals and gorgonians are animals. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Posidonia is a plant, not an algae. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Marine forests act as nurseries for commercially valuable species. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Some animals live attached to the seafloor. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Duration: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Materials used: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Explanations: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Interesting: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Surprising: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Boring: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Repetitive: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Useful for learning new things: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Would recommend it: ☐1 ☐2 ☐3 ☐4 ☐5

- Thanks to technological advances, there are now less harmful ways to study the ocean. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- There are special robots for exploring the sea. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Seawater contains microscopic life that appears as “marine snow.” ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Teamwork is essential to study the sea well. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- There is high biodiversity in the Balearic Sea. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Some algae look like rocks (grapissar). ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Did you know about trawling? ☐ Yes ☐ No

- Marine forests are seriously threatened by trawling. ☐ Yes ☐ No

- When you return to the water, will you notice more than before? ☐ Yes, a lot ☐ Yes, a little ☐ No

- Will you see the sea differently? ☐ Yes, a lot ☐ Yes, a little ☐ No

- Do you want to learn more about the sea? ☐ Yes, a lot ☐ Yes, a little ☐ No

- Would you like to tell others about the sea? ☐ Yes, a lot ☐ Yes, a little ☐ No

- Did it help you learn about the sea? ☐ Yes, a lot ☐ Yes, a little ☐ No

References

- Kiousopoulos, J. Exploring Littoral Space by means of ‘Coastality’. Mar. J. 2014, 1, 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall, C. Backs to the sea? Least-cost paths and coastality in the Southern Early Bronze Age IIA Aegean. In Islands in Dialogue (Islandia): Proceedings of the First Postgraduate Conference in the Prehistory and Protohistory of the Mediterranean Islands, Turin, Italy, 14–16 November 2018; Torrossa Open: Florence, Italy, 2021; pp. 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Integrated Coastal Area Management and Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/a0266e/a0266e07.htm (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- United States Commission on Marine Science, Engineering and Resources. Our Nation and the Sea A Plan for National Action. 1969. Available online: https://www.coastalstates.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Stratton-Comm-Report.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Coastal Area. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:Coastal_area (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Copernicus Land Monitoring Service. Coastal Zones. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/coastal-zones?tab=technical_summary (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- EU4Ocean Coalition. EU Blue Schools Application Guidelines. Available online: https://maritime-forum.ec.europa.eu/form/become-european-blue-school_en (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Proshansky, H.M. The City and Self-Identity. Environ. Behav. 1978, 10, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, P.M.; Glithero, L.D.; McKinley, E.; Strand, M.; Champion, G.; Kochalski, S.; Velentza, K.; Praptiwi, R.A.; Jung, J.; Márquez, M.C.; et al. A transdisciplinary co-conceptualisation of marine identity. People Nat. 2024, 6, 2300–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, C.M.; Rivera, M.A.J. A longitudinal analysis of developing marine science identity in a place-based, undergraduate research experience. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.; Garriga, A.; Bosch, M.T.; Bosch, M.; Villasante, S.; Salazar, J. Ocean literacy in managing marine protected areas: Bridging natural and cultural heritage. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1540163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.F. Space and Place the Perspective of Experience. 1977. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/19846369/Yi_Fu_Tuan_Space_and_Place (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Nuttall, C. Seascape Dialogues: Human-Sea Interaction in the Aegean from Late Neolithic to Late Bronze Age. Ph.D. Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lištiaková, I.L.; Preece, D. The Experiences of Families on the Autism Spectrum in Rural Coastal Communities in England. In Including Voices: Respecting the Experiences of People From Marginalised Communities; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larjosto, V. Islands of the Anthropocene. Area 2020, 52, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodini, A.-A.; Vouza, A.-R.; Kalergis, D.; Kyvelou, S.S. Strategic Participatory Planning and Social Management for Clustering Maritime Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of the West Pagasetic Gulf, Greece. Heritage 2025, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R. Political geography I: Blue geopolitics. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2024, 48, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, S.; Talhelm, T.; Lee, M. Personality and geography: Introverts prefer mountains. J. Res. Pers. 2015, 58, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terradas i Saborit, I. La Contradicción Entre Identidad Vivida e Identificación Jurídico. 2004. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/QuadernsICA/article/view/95585/165160 (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Cebrián, G.; Junyent, M.; Mulà, I. Current Practices and Future Pathways towards Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut Cartogràfic i Geogràfic de les Illes Balears. Litoral de les Illes Balears. Available online: https://apps.caib.es/sites/icgibinfo/es/inici/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Govern de les Illes Balears. Instituto de Estadística de les Illes Balears. Territorio y Medio Ambiente. Available online: https://ibestat.es/estadistica/territorio-medio-ambiente/territorio (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Agència d’Estratègia Turística de les Illes Balears. Lloret de Vistalegre. Available online: https://www.illesbalears.travel/es/mallorca/municipios/lloret-de-vistalegre (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- United Nations. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. 1982. Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Govern de les Illes Balears. Llei 6/2013, de 7 de novembre, de pesca marítima, marisqueig i aqüicultura a les Illes Balears 1. 2013. Available online: https://intranet.caib.es/sites/institutestudisautonomics/f/300047 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Goffriller, M. The castral territory of the Balearic islands: The evolution of territorial control in Mallorca during the middle ages. In Chateau et Représentations; Actes du Colloque International de Stirling (Ecosse); Centre de Recherches Archéologiques et Historiques Médiévales (CRAHM): Caen, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Goffriller, M. The Castles of Mallorca A Diachronic Perspective of the Dynamics of Territorial Control on an Islamic Island; University of Exeter: Exeter, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Armas-Díaz, A.; Murray, I.; Sabaté-Bel, F.; Blázquez-Salom, M. Environmental struggles and insularity: The right to nature in Mallorca and Tenerife. Environ. Plan. C: Politics Space 2024, 42, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, M.; Molina, D.J.; Santacreu, D.A.; Rossello, J.G. Enhancing ‘Places’ Through Archaeological Heritage in Sun, Sand, and Sea Touristic Coastal Areas: A Case Study From Mallorca (Spain). J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2014, 9, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picornell, M. Insular identity and urban contexts: Representations of the local in the construction of an image of Palma (Mallorca, Balearic Islands). Isl. Stud. J. 2014, 9, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián, J.B.; Garau, A.O. Alfabetización en Geografía y mapas mentales. Los conocimientos mínimos entre los estudiantes universitarios de Educación Primaria. Cuad. Geográficos 2018, 57, 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián, J.B.; Garau, A.O.; Pérez, M.R. Assessing geography knowledge in primary education with mental map analysis: A Balearic Islands case study. Educ. Stud. 2024, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Gili, J.-M.; Millán, L.; Vendrell-Simón, B.; Gómez, S. Ocean Literacy Opportunities in Urban Marine Ecosystems: Gorgonian Populations in Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain). Ocean. Soc. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Marambio, M.; Ballesteros, A.; Vendrell-Simón, B.; Gili, J.-M. Reframing jellyfish perception from ‘enemies’ to ‘helpers’ through Ocean Literacy. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1636803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBESTAT. Institut d’Estadística de les Illes Balears. Available online: https://ibestat.es/aviso-legal/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Cifras oficiales de población de los municipios españoles: Revisión del Padrón Municipal a 1 de enero de 2024. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?L=0&t=2860 (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Associacions de Can Picafort. Can Picafort; Associacions de Can Picafort: Can Picafort, Mallorca, Spain, 1991; No. 107; Available online: https://ibdigital.uib.es/greenstone/collect/premsaForanaMallorca/index/assoc/Can_Pica/fort_199/1_mes08_.dir/Can_Picafort_1991_mes08_n0107.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2025).

- European Commission. Become a European Blue School. Available online: https://maritime-forum.ec.europa.eu/theme/ocean-literacy-and-blue-skills/ocean-literacy/network-european-blue-schools/become-european-blue-school_en (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Esteva-Burgos, C.; Ruiz-Pérez, M. Modeling Spatial Determinants of Blue School Certification: A Maxent Approach in Mallorca. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2025, 14, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU4Ocean Coalition—European Commission. Som Escoles Blaves—A Beacon for Ocean Literacy in the Balearic Islands. Available online: https://maritime-forum.ec.europa.eu/som-escoles-blaves-beacon-ocean-literacy-balearic-islands_en (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Sánchez-Cuenca, P. Conducta Ètica/Bloc A (Ethical Conduct/Block A); Escola Balear d’Administració Pública (EBAP), Govern de les Illes Balears: Palma de Mallorca, Spain, 2016. Available online: https://ebapenobert.caib.es/pluginfile.php/4336/mod_resource/content/6/Competencies_1_i_2_PDF.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation). Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L 119, 1–88. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/679/oj (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- BOE. Ley Orgánica 3/2018, de 5 de diciembre, de Protección de Datos Personales y garantía de los derechos digitales. Boletín Off. Estado 2018, 294, 119875–120022. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2018/12/05/3/con (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- McKinley, E.; Burdon, D.; Shellock, R.J. The evolution of ocean literacy: A new framework for the United Nations Ocean Decade and beyond. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, F.; Schoedinger, S.; Strang, C.; Tuddenham, P. Science Content and Standards for Ocean Literacy: A Report on Ocean Literacy; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); National Geographic Society; COSEE; NMEA: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.coexploration.org/oceanliteracy/documents/OLit2004-05_Final_Report.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Schoedinger, S.; Cava, F.; Strang, C.; Tuddenham, P. Ocean literacy through science standards. In Proceedings of the MTS/IEEE OCEANS, Washington, DC, USA, 17–23 September 2005; IEEE Computer Society. pp. 736–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- United Nations. United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development 2021–2030 (A/RES/72/73). Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/decades/ocean-decade (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- United Nations. United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development Implementation Plan. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377082 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Fauville, G.; Strang, C.; Cannady, M.A.; Chen, Y.-F. Development of the International Ocean Literacy Survey: Measuring knowledge across the world. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 238–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markos, A.; Boubonari, T.; Mogias, A.; Kevrekidis, T. Measuring ocean literacy in pre-service teachers: Psychometric properties of the Greek version of the Survey of Ocean Literacy and Experience (SOLE). Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Coral, E.; Deprez, T.; Mokos, M.; Vanreusel, A.; Roose, H. The Blue Survey: Validation of an instrument to measure ocean literacy among adults. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2022, 23, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoors, F.; Leakey, C.D.B.; James, M.A. Piloting a Regional Scale Ocean Literacy Survey in Fife. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 858937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs. Ocean Literacy Headline Report. 2022. Available online: www.gov.uk/defra (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Macneil, S. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education. Yumagulova. 2019. Available online: http://www.colcoalition.ca (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Ortanderl, F.; Bausch, T. Wish you were here? Tourists’ perceptions of nature-based destination photographs. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2023, 29, 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Dominguez-Carrió, C.; Gili, J.-M.; Ambroso, S.; Grinyó, J.; Vendrell-Simón, B. Building a New Ocean Literacy Approach Based on a Simulated Dive in a Submarine: A Multisensory Workshop to Bring the Deep Sea Closer to People. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, D.; Smith, J.L. GIS for Coastal Zone Management; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttall, C. A GIS Analysis of Coastal Proximity with a Prehistoric Greek Case Study. J. Comput. Appl. Archaeol. 2024, 7, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Systems Research Institute. Esri, ArcGIS Pro, Version 3.4. Available online: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Power BI. Available online: https://powerbi.microsoft.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Swami, V.; White, M.P.; Voracek, M.; Tran, U.S.; Aavik, T.; Ranjbar, H.A.; Adebayo, S.O.; Afhami, R.; Ahmed, O.; Aimé, A.; et al. Exposure and connectedness to natural environments: An examination of the measurement invariance of the Nature Exposure Scale (NES) and Connectedness to Nature Scale (CNS) across 65 nations, 40 languages, gender identities, and age groups. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 99, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.J.; White, M.P.; Davison, S.M.; Zhang, L.; McMeel, O.; Kellett, P.; Fleming, L.E. Coastal proximity and visits are associated with better health but may not buffer health inequalities. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional Affinity toward Nature as a Motivational Basis to Protect Nature. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P. Dispositional empathy with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 35, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umargono, E.; Suseno, J.E.; Gunawan, S.K.V. K-Means Clustering Optimization Using the Elbow Method and Early Centroid Determination Based on Mean and Median Formula. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Seminar on Science and Technology (ISSTEC 2019), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 25 November 2019; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, L.; Gifford, R. Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, L.; Donald, N.-S. The Production of Space; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Yemini, M.; Engel, L.; Simon, A.B. Place-based education—A systematic review of literature. Educ. Rev. 2023, 77, 640–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikner, T.; Piwowarczyk, J.; Ruskule, A.; Printsmann, A.; Veidemane, K.; Zaucha, J.; Vinogradovs, I.; Palang, H. Sociocultural Dimension of Land–Sea Interactions in Maritime Spatial Planning: Three Case Studies in the Baltic Sea Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.; Gupta, A. Connecting to the Sea: A Place-Based Study of the Potential of Digital Engagement to Foster Marine Citizenship. Urban Plan. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak-Brown, J. Gaps and Opportunities for Local Resilience Planning in Connecticut. UConn Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation. 2022. Available online: https://resilientconnecticut.uconn.edu/localresilienceplanning/ (accessed on 25 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.C.; Camerin, F. The application of ecosystem assessments in land use planning: A case study for supporting decisions toward ecosystem protection. Futures 2024, 161, 103399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepath, C.M. Marine education: Learning evaluations. J. Mar. Educ. 2007, 23, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- O’Halloran, C. Impact of ocean connectedness, environmental identity, emotions, and ocean activities on pro-environmental behaviors. Front. Ocean. Sustain. 2025, 3, 1518099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| School | Primary 5th 10-Years | Primary 6th 11-Years | 1st Year of Secondary Education 12-Years | 2nd Year of Secondary Education 13-Years | 3rd Year of Secondary Education 14-Years | 4th Year of Secondary Education 15-Years | 1st Year of Upper Secondary Education | 1st Year of VET (Vocational Education Traing) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEIP Miquel Capllonch | 9 | 9 | |||||||

| CEIP Na Caragol | 40 | 14 | 54 | ||||||

| CEIP s’Alzinar | 15 | 15 | |||||||

| IES Artà | 37 | 45 | 1 | 83 | |||||

| IES Capdepera | 16 | 19 | 26 | 12 | 27 | 15 | 115 | ||

| IES Guillem C. de Colonya | 24 | 1 | 25 | ||||||

| IES Manacor | 34 | 34 | |||||||

| Sant Bonaventura | 24 | 14 | 23 | 19 | 80 | ||||

| Sant Francesc d’Assís | 24 | 1 | 25 | 19 | 16 | 85 | |||

| Sant Salvador | 17 | 19 | 22 | 15 | 73 | ||||

| Santo Tomás de Aquino | 21 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 1 | 72 | |||

| Total | 78 | 97 | 153 | 77 | 137 | 64 | 27 | 15 | 645 |

| Variable | Description | Type and Coding |

|---|---|---|

| coastal-inland identification | Student coastal-inland identification of their hometown | Ordinal 0 to 1 |

| Emotional connection to the sea | Emotional polarity and intensity toward the sea | Ordinal (−2 to +3) |

| Frequency of coastal visits | Frequency of visits to coastal areas | Continuous (0 to 10) |

| Local ocean literacy level | Knowledge of local marine terms | Continuous (0 to 10) |

| Global ocean literacy level | General ocean literacy knowledge | Continuous (0 to 10) |

| Marine sports and activities | Number of different marine activities practiced | Continuous (0 to 6) |

| Talking about the sea | Number of social agents discussing the sea | Continuous (0 to 10) |

| Sources of information | Number of information sources regarding the sea | Continuous (0 to 10) |

| Local species knowledge | Ability to identify local marine species | Continuous (0 to 10) |

| Municipality | Coastal | Coastal and Inland | Inland | Not Specified | Distance to Coast in km |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artà | 33.72% | 3.49% | 54.65% | 8.14% | 12.8 |

| Cala rajada | 83.61% | 1.64% | 8.20% | 6.56% | 0 |

| Capdepera | 64.29% | 2.38% | 27.38% | 5.95% | 2.6 |

| Colònia de sant pere | 85.00% | 10.00% | 5.00% | 0 | |

| Inca | 6.52% | 4.35% | 89.13% | 23.4 | |

| Manacor | 18.58% | 0.88% | 75.22% | 5.31% | 11.8 |

| Pollença | 88.00% | 4.00% | 8.00% | 6.68 | |

| Sant llorenç des cardessar | 40.91% | 4.55% | 40.91% | 13.64% | 11.5 |

| Total | 43.19% | 2.65% | 47.79% | 6.37% |

| Population Center | Inland Gap Index | Population Center | Inland Gap Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Son macià | 0.717 | Muro | 0.167 |

| Sa pobla | 0.667 | Sant llorenç des cardassar | 0.159 |

| Son carrió | 0.639 | Colònia de sant pere | 0.105 |

| Caimari | 0.554 | Cala rajada | 0.089 |

| Mancor de la vall | 0.497 | Portocolom | 0 |

| Selva | 0.483 | Cala mesquida | 0 |

| Manacor | 0.411 | Canyamel platja | 0 |

| Lloseta | 0.383 | Can picafort | 0 |

| Artà | 0.338 | Porto cristo | 0 |

| Inca | 0.295 | Port d’alcúdia/alcanada | 0 |

| Capdepera | 0.267 | Port de pollença | 0 |

| Son servera | 0.260 | Sa coma | −0.010 |

| Cala millor | 0.25 | S’illot | −0.010 |

| Vilafranca de bonany | 0.215255439 | Alcúdia | −0.014 |

| Pollença | −0.071 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esteva-Burgos, C.; Salazar, J.; Vendrell-Simón, B.; Gili, J.M.; Ruiz-Pérez, M. Rethinking Coastal Areas Through Youth Perceptions and the Coastality Gap Index: A Case Study of the Island of Mallorca. World 2025, 6, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040158

Esteva-Burgos C, Salazar J, Vendrell-Simón B, Gili JM, Ruiz-Pérez M. Rethinking Coastal Areas Through Youth Perceptions and the Coastality Gap Index: A Case Study of the Island of Mallorca. World. 2025; 6(4):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040158

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsteva-Burgos, Christian, Janire Salazar, Begoña Vendrell-Simón, Josep Maria Gili, and Maurici Ruiz-Pérez. 2025. "Rethinking Coastal Areas Through Youth Perceptions and the Coastality Gap Index: A Case Study of the Island of Mallorca" World 6, no. 4: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040158

APA StyleEsteva-Burgos, C., Salazar, J., Vendrell-Simón, B., Gili, J. M., & Ruiz-Pérez, M. (2025). Rethinking Coastal Areas Through Youth Perceptions and the Coastality Gap Index: A Case Study of the Island of Mallorca. World, 6(4), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040158