1. Introduction

The decision of migrants to select particular routes into Europe is profoundly influenced by a multifaceted array of demographic, socioeconomic, and institutional dynamics, among which the Western Balkan corridor stands out as a pivotal conduit due to its geographical proximity to the European Union, longstanding historical usage, and the entrenched networks that facilitate passage [

1]. This pathway, channeling flows primarily from the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, has evolved into a resilient artery for those seeking asylum and opportunity in the EU, underscoring the interplay between structural barriers and adaptive human strategies. Our analysis zeroes in on the divergent choices between two primary entry points along this route (Bulgaria and Greece), drawing on comprehensive data from the International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) Flow Monitoring Survey spanning August 2022 to June 2025 (

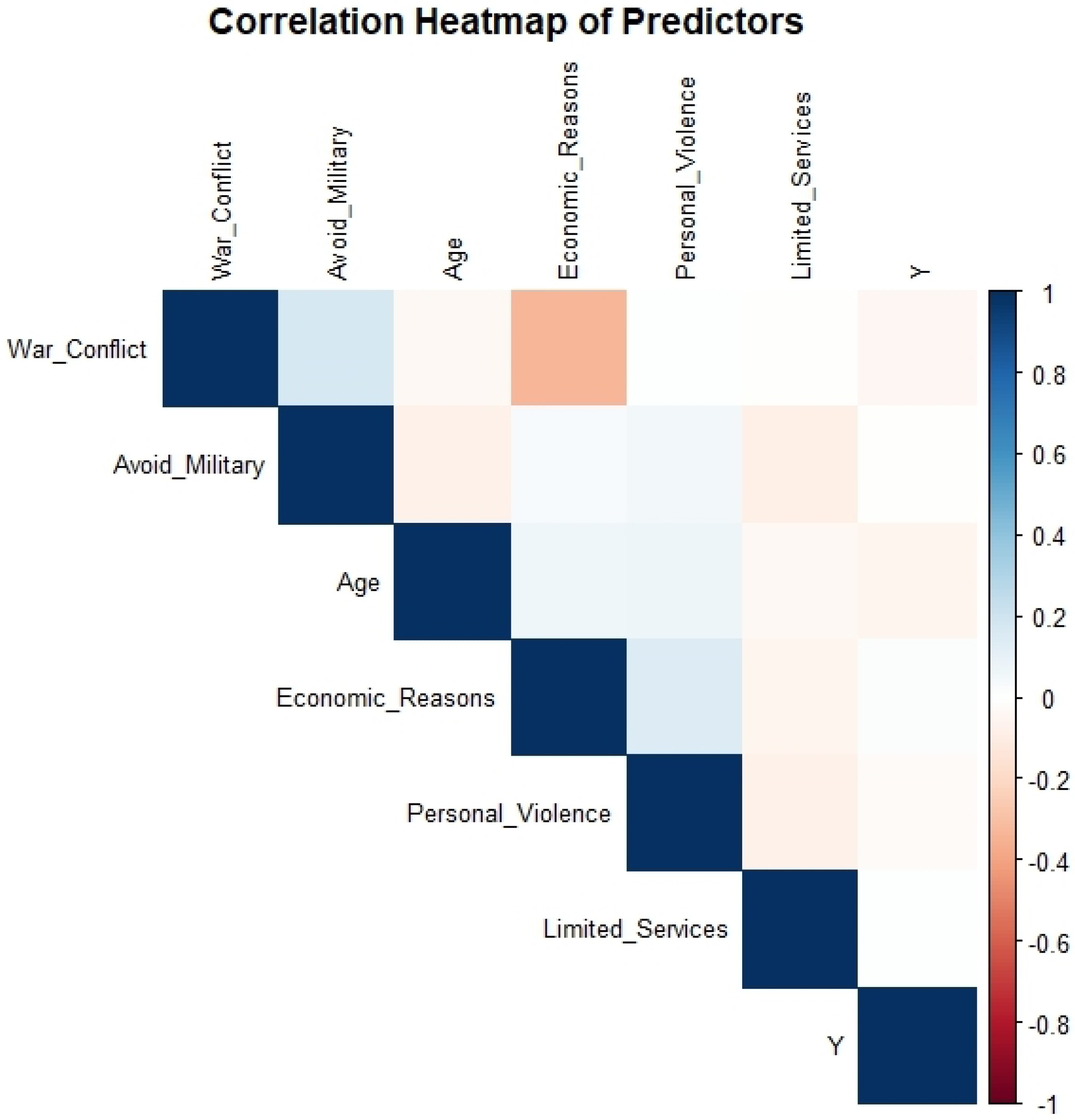

). Employing a logistic regression framework, we model the binary outcome of route selection (Bulgaria = 1, Greece = 0) by integrating key demographic variables (such as age), push factors (including economic hardship, war and conflict, personal violence, limited access to services, and avoidance of military service), and governance clusters derived from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators. These clusters, informed by k-means analysis of corruption control, government effectiveness, rule of law, and voice and accountability metrics, enable a nuanced examination of institutional affinities that shape migratory decisions. Recognizing the inherent constraints of traditional regression in capturing non-linearities and complex interactions, we augment our approach with machine learning extensions. To be specific, we use LASSO-regularized logistic regression and Random Forests, and by doing so, we try to enhance predictive robustness and uncover subtler patterns [

2]. At its core, this study poses a central research question: what factors drive migrants’ preferences for entering Europe via Bulgaria over Greece? To probe this, we advance and test three hypotheses rooted in push–pull dynamics and institutional theory:

H1: Younger migrants are more inclined to opt for Bulgaria, drawn by its perceived accessibility.

H2: Constraints such as limited access to services in origin country heighten the appeal of Bulgaria, whereas predominantly economic motivations tilt preferences toward Greece.

H3: Elevated corruption in origin countries propels migration flows while steering transit preferences toward destinations exhibiting comparable governance profiles, thereby embedding corruption as a pivotal push–pull mechanism within an adapted migration gravity model.

Empirical trends from recent IOM reports illuminate Bulgaria’s ascendance as a formidable entry hub, accounting for around one third of surveyed crossings, fueled by resonant governance structures and parity in facilitation expenditures (approximately €1000 per route) [

3]. Nevertheless, we should acknowledge the most recent declines in this specific route. This research not only delineates the determinants of route choice but also refines foundational migration paradigms. Ultimately, it furnishes actionable insights to bolster migration governance, spanning preventive measures at origins, streamlined management in transit zones, and integrative strategies at destinations. The remainder of this article is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical and empirical literature on migration drivers, with particular attention to corruption and governance as push–pull factors.

Section 3 introduces the data sources, variable construction, and governance clustering procedure, followed by a subsection that outlines the empirical strategy, including logistic regression and machine learning models.

Section 4 presents the main results, covering descriptive statistics, regression estimates, and model comparisons.

Section 5 discusses the implications of our findings in light of existing theories and governance measurement debates. In the same section, we outline policy recommendations for origin, transit, and destination contexts. Here we offer highlights, limitations, and avenues for future research. The final section concludes by summarizing the contribution of this study to the broader migration literature.

2. Literature Review

The intricate decision-making process behind migrants’ choice of routes into Europe, as introduced earlier, builds upon a rich field of theoretical foundations that seek to unravel the multifaceted drivers shaping the Western Balkan corridor’s role as a critical conduit. Foundational theories, such as Ravenstein’s laws [

4,

5] and Lee’s push–pull framework [

6], have long framed migration as a response to economic, social, and environmental imbalances, offering a lens through which to interpret the flows entering via Bulgaria and Greece. These classic perspectives are enriched by modern frameworks, notably de Haas’s aspirations–capabilities model [

1] and Williams’s multi-level approach [

7], which provide deeper insights into the interplay of personal ambitions, structural barriers, and governance dynamics influencing route preferences along this route.

Recent studies have emphasized the role of institutional quality in shaping economic development, which in turn influences migration patterns [

8]. This underscores the need to consider governance structures when analyzing push factors in origin countries along the Balkan route. Lee’s classic theory of migration [

6] highlights the interplay of push and pull factors, offering a foundational perspective that informs our analysis of economic and governance drivers.

This study highlights the complex interplay of demographic, motivational, and governance factors in migration route choices along the Balkan route. The Cluster Model highlights the importance of governance factors, with younger migrants preferring Bulgaria and high-corruption origins influencing route selection. Machine learning approaches confirm the moderate predictive power, suggesting route choices are multifaceted. Corruption influences both departure and transit preferences, aligning with the gravity model. Future research should refine governance clusters, incorporate real-time flow data, explore additional machine learning techniques, and use dynamic models to capture evolving migration patterns [

2].

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks

The Push–Pull Theory remains a cornerstone, delineating adverse conditions, such as conflict, corruption, and limited access to services, as push factors that propel migrants from their origins. On the other hand, opportunities like economic stability and lower corruption levels act as pull factors drawing them toward destinations [

6,

9]. This framework aligns seamlessly with our study’s focus on how governance similarities and facilitation costs shape choices between Bulgaria and Greece, not as destination countries but as one of the stages of migrants’ journey. Complementing this, the Gravity Model, originally centered on distance, has evolved to integrate socioeconomic and political variables, including corruption control, offering a refined tool to analyze migration flows [

10,

11]. Unlike its trade-oriented counterparts [

12], migration variants of the gravity model prioritize institutional factors over mere geographic proximity [

13], resonating with our exploration of governance clusters as determinants of route selection. Meanwhile, the aspirations–capabilities framework underscores how individual aspirations, constrained or enabled by structural factors like corruption, guide migratory decisions [

1,

7], providing a theoretical bridge to our hypotheses on age, service access, and corruption’s dual role. Beine et al. [

10] provide a comprehensive guide to applying gravity models in migration research, offering a methodological foundation for our adapted model that incorporates corruption as a key variable.

Massey’s work on cumulative causation [

14] and theoretical synthesis of immigration drivers [

15] provides a historical lens for understanding how structural and household-level factors perpetuate migration along routes like the Balkans. To formalise this integration, we adapt the standard gravity specification as follows:

where

represents the migration flow or, in our case, the probability that an individual from origin

i selects route

j at time

t. The classical components—population size, economic mass (GDP), and distance—capture structural constraints on movement, while the term

introduces the corruption differential between origin and transit contexts as a governance-based friction or attraction factor. We operationalise

as the binary probability of entry via Bulgaria (

) versus Greece (

). This translation allows the model to approximate spatial interactions at the individual decision level, consistent with the gravity intuition but suited to cross-sectional survey data. The coefficient

thus measures the extent to which governance and corruption similarities function as push–pull mechanisms in shaping migrants’ route selection, offering an empirical bridge between institutional theory and micro-level behavioural evidence.

2.2. Corruption as a Push–Pull Factor

Corruption emerges as a pivotal driver within this theoretical landscape, quantified through the World Bank’s Control of Corruption indicator (CC.EST). It undermines economic prospects and security in high-corruption origin countries like Afghanistan and Syria, pushing migrants toward lower-corruption destinations such as Germany and France [

16,

17]. In the transit context, countries like Bulgaria and Greece, characterized by moderate corruption, facilitate passage through relaxed enforcement or bribery, mirroring conditions in migrants’ home regions [

3,

18]. This dual push–pull dynamic challenges the traditional gravity model’s emphasis on distance [

19], aligning with our hypothesis that corruption steers preferences toward governance-similar transit routes, a finding underscored by Bulgaria’s rising prominence (38.8% of entries), as noted in recent IOM data. Empirical evidence from European contexts suggests that corruption acts as both a push factor from origin countries and a pull factor influencing transit preferences, a dynamic explored by Bernini et al. [

18] and relevant to the Balkan route.

2.3. Quantitative Modeling of Migration

The complexity of modeling migration, a theme central to our methodological approach, stems from its diverse drivers—ranging from individual attributes like age to macro-level factors such as war and governance [

20]. Gravity models, leveraging GDP, population, and governance indicators, offer predictive power for migration flows [

10], yet their distance-centric focus may undervalue human agency [

13]. To address this, our study integrates corruption into an adapted gravity model, using IOM survey data and World Governance Indicator (WGI) clusters. Additionally, machine learning techniques, including Random Forests and regularized regression, enhance the capture of non-linear relationships and interactions, though their interpretability remains a challenge [

2,

21]. This dual approach strengthens our analysis of route choices, extending beyond traditional models to validate findings with robust predictive tools.

2.4. Application to the Balkan Route

The Balkan route, highlighted in our introduction as a key migratory pathway, positions Bulgaria and Greece as critical entry points where governance affinities and cost factors, such as the €1000 facilitation fee, drive Bulgaria’s increasing share of entries (38.8%) [

3,

18]. This study advances the application of the gravity model by synthesizing micro-level IOM survey data with macro-level governance clusters and machine learning, offering a comprehensive exploration of corruption’s influence on route selection. This synthesis not only aligns with the theoretical frameworks discussed but also informs our policy recommendations across origin, transit, and destination phases, bridging the gap between empirical trends and actionable governance strategies.

Recent research has significantly deepened the understanding of the intricate decision-making processes guiding migrants’ route selections through the Western Balkans, emphasizing the evolving interplay of economic, governance, and corruption factors that continue to shape this critical corridor. Hence, higher corruption levels may deter migration in some contexts due to increased barriers or risks, whereas improvements in political stability and the rule of law correlate with reduced migration flows, and enhanced government effectiveness can slightly boost mobility through better infrastructure or administrative support [

22].

The latest findings underscore that perceived corruption in the Western Balkans propels migrants toward less corrupt, more stable European countries, a trend supported by network effects where existing migrant communities abroad strongly influence new flows; additional factors such as per capita GDP differences, bilateral distances, and large-scale crises like COVID-19 further shape these evolving patterns [

23,

24]. This aligns with the paper’s adapted gravity model, which integrates corruption as a key push–pull mechanism, and its empirical strategy using governance clusters from the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators.

3. Materials and Methods

The IOM publicly available reports can be compiled into a dataset that comprises 15,291 responses, filtered to 5536 respondents with valid entry route data (Bulgaria = 2150, Greece = 3386). The binary outcome is

3.1. Data

This dataset, aligned with the theoretical frameworks of push–pull dynamics and the adapted gravity model, enables a robust analysis of how demographic, socioeconomic, and governance factors—central to our hypotheses—shape these decisions. Below, we detail the predictors, governance clusters, and data handling procedures that connect the theoretical constructs to our empirical investigation.

The dependent variable in our analysis was derived directly from the question: “Which country did you first enter upon arriving in the European Union?” Responses were coded as if the respondent entered via Bulgaria and if via Greece. This binary operationalisation allows for a focused examination of route determinants between the two primary Eastern Mediterranean entry points. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the Western Balkan corridor also includes secondary routes such as Albania and North Macedonia.

3.1.1. Predictors

The selection of predictors reflects the multifaceted drivers identified in migration literature, linking individual attributes with macro-level conditions. Key predictors include:

Age (continuous, mean = 25.94, SD = 6.60), a variable tied to Hypothesis 1, capturing the preference of younger migrants for Bulgaria due to perceived accessibility and lower risks.

Economic Reasons (binary, 61%), a push factor that, per Hypothesis 2, may favor Greece as a route driven by economic opportunities.

War/Conflict (binary, 59%), a dominant push factor influencing route choices from conflict-affected origins, resonating with the aspirations–capabilities framework.

Personal Violence (binary, 31%), highlighting individual-level security concerns that may steer migrants toward specific transit routes.

Limited Access to Services (binary, 25%), another push factor in Hypothesis 2, potentially increasing Bulgaria’s appeal due to service deficiencies in origin areas.

Avoid Military Service (binary, 11%), reflecting personal motivations that may influence route preferences based on governance similarities.

These predictors, detailed in

Table 1, provide a micro-level foundation to test the interplay of demographic and push–pull factors, bridging the theoretical emphasis on human agency with empirical measurement.

3.1.2. Governance Clusters

Building on the literature’s focus on corruption as a push–pull factor, governance clusters are derived from World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicator (WGI) data (2018–2022), encompassing Control of Corruption (CC.EST), Government Effectiveness (GE.EST), Rule of Law (RL.EST), and Voice and Accountability (VA.EST). These indicators were clustered into four groups using k-means (

Table 2), a method that aligns with our adapted gravity model’s emphasis on institutional factors over distance. Fuzzy matching aligned country names with unmatched origins (e.g., Congo and Iran) assigned to an

Unknown cluster. Cluster distributions reveal:

Origins: Cluster 4 (fragile/conflict-affected, 2370), Cluster 3 (transitional, 699), Cluster 1 (mixed governance, 21), Unknown (2446), reflecting the diverse governance contexts driving migration as per Hypothesis 3.

Destinations: Cluster 2 (high governance, 5326), Cluster 3 (19), Unknown (191), underscoring the pull of stable governance destinations.

This clustering approach enhances our analysis of how corruption and governance affinities, a key theme in the literature, influence route selection, particularly Bulgaria’s rising prominence (38.8% of entries).

The choice of four clusters () was determined empirically using the elbow and silhouette methods, both of which indicated diminishing returns in within-cluster variance beyond four groups. Conceptually, this structure aligns with the typology of governance regimes identified in prior research: (1) high-governance democracies, (2) transitional or hybrid systems, (3) mixed or intermediate performers, and (4) fragile or conflict-affected states. This classification captures the institutional gradient most relevant to migration dynamics along the Balkan route, where migrants often originate from cluster 4 contexts but transit through or aspire toward cluster 2 destinations.

A major challenge lies in the 44% of cases categorized as “Unknown,” stemming primarily from origin countries not fully represented in the WGI dataset due to limited data availability or missing governance scores. Instead of excluding these observations, we retained them as a separate analytical category to avoid biasing results toward data-rich regions.

Interpreting these clusters within the adapted gravity framework allows governance similarity—particularly in corruption control—to function as a spatial “proximity” variable beyond geography.

3.1.3. Missing Data and Imputation

To ensure the integrity of our dataset, missing values (Age: 41, push factors: 956 each) were addressed using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) with imputations. Predictive mean matching was applied for continuous variables like age, while logistic regression handled binary push factors, preserving the outcome distribution (Greece = 3386, Bulgaria = 2150).

3.2. Methods

Salamońska [

21] advocates for robust quantitative methods in migration research, guiding our use of logistic regression and clustering techniques to analyze IOM data.

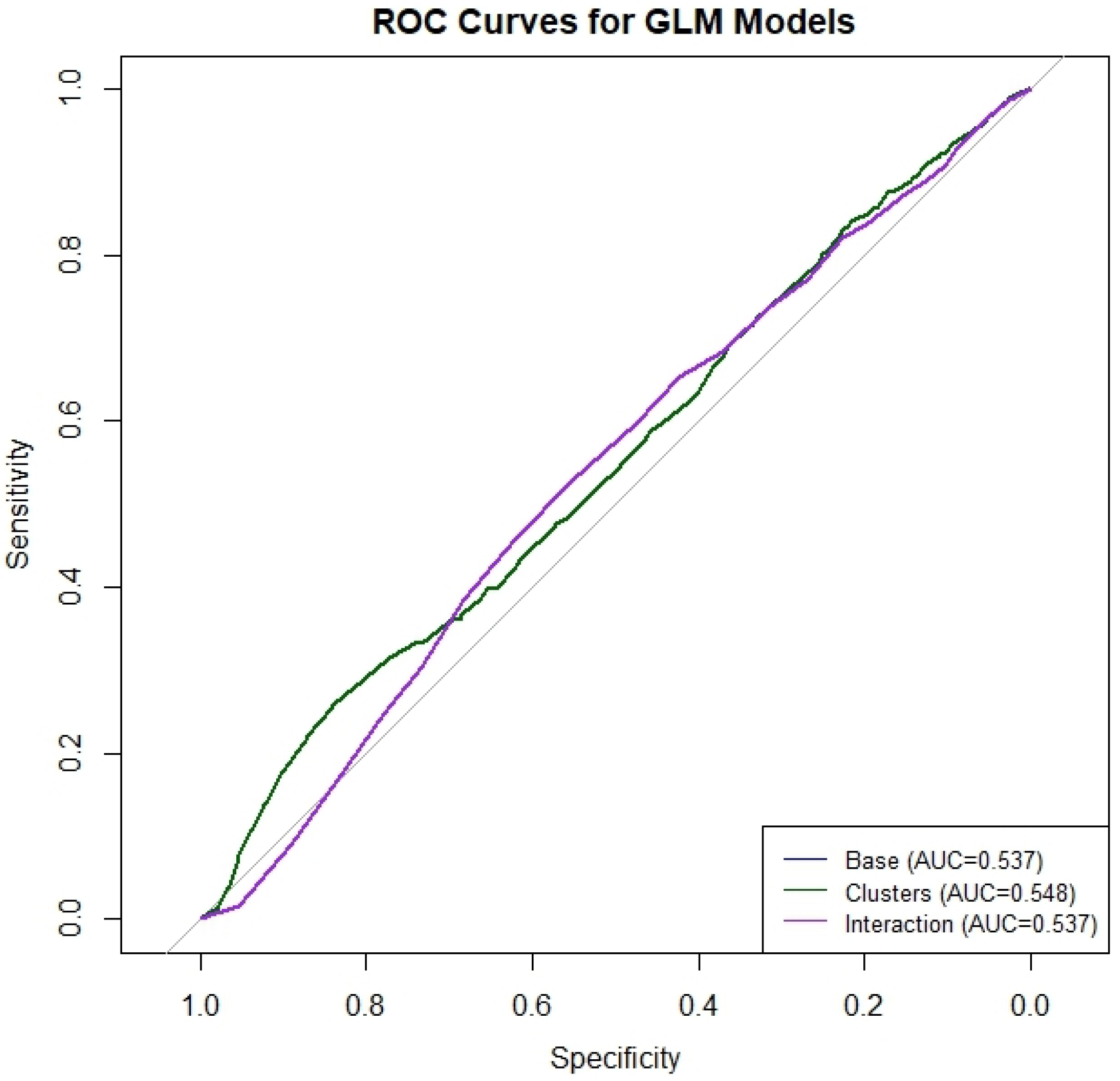

Three logistic regression models were estimated:

Base Model: Age and push factors.

Cluster Model: Adds governance clusters.

Interaction Model: Includes Age × Economic Reasons.

The linear predictor for the Base Model is

Parameters are estimated via maximum likelihood:

Fit is assessed via AIC, log-likelihood, McFadden’s , ROC/AUC, and confusion matrices. K-means clustering () grouped countries by governance indicators.

To extend the analysis, we applied machine learning techniques on a subset of the data () with three key predictors (age, economic reasons, and war/conflict) to focus on core variables and test for improved performance:

LASSO-regularized logistic regression [

25] uses the glmnet package in R, with 5-fold cross-validation and tuning over lambda values (alpha fixed at 1 for L1 penalty). The LASSO model minimizes the following objective function:

where

n is the number of observations,

p is the number of predictors, and

is the regularization parameter.

Random Forests [

26] uses the randomForest package via the caret framework, with tuning over mtry parameters (tuneLength = 5) and 5-fold cross-validation. Random Forest constructs an ensemble of

B decision trees, each trained on a bootstrapped sample of the data and using a random subset of features at each split. For classification, the predicted class for a new observation

is

where

is the prediction from the

b-th tree, and

I is the indicator function.

Models were evaluated using ROC-AUC on a held-out test set.

5. Discussion

This study advances the migration gravity model by integrating corruption as a dual-force determinant, building on the theoretical frameworks and governance-focused analyses presented earlier. Head and Mayer [

12] demonstrate the utility of gravity models in evaluating economic freedoms, suggesting that our adapted model’s inclusion of corruption could enhance its predictive power for migration flows. By merging micro-level survey evidence with macro-level governance clustering, we provide a more holistic account of migrant route decisions along the Western Balkan corridor. Our findings corroborate prior work emphasizing the salience of corruption as both a push factor from origins and a structuring element in transit routes [

16,

18]. The statistical evidence robustly supports Hypothesis 1, with younger migrants exhibiting a significant preference for Bulgaria (

,

), a pattern consistent with literature on age-related mobility strategies and risk perception [

1]. In this context we should mention that Williams et al. [

7] find that younger adults exhibit distinct migration intentions, aligning with our observation of age influencing route choices toward Bulgaria.

Governance clustering further reinforces Hypothesis 3, showing that migrants from fragile, high-corruption origins (Cluster 4,

) disproportionately select Bulgaria, reflecting institutional affinities that facilitate transit [

3]. This institutional dimension enriches the gravity model by extending beyond geography to encompass governance similarity, echoing calls by Fitzgerald et al. [

19] and Beine et al. [

10] for models that incorporate institutional variables. Yet the Cluster Model’s modest improvement over the Base (AIC = 7367 vs. 7374) and Interaction (AIC = 7391) models reveals that governance influences, while meaningful, operate subtly and may interact with unmeasured situational factors such as smuggling networks or temporary border policies.

Machine learning extensions (LASSO and Random Forests) confirmed these nuances by failing to deliver major predictive gains (AUC = 0.515–0.524). This result is consistent with concerns raised by Beyer et al. [

2,

13], who argue that migration dynamics are poorly captured by static predictors alone and often shaped by shocks, contingencies, and path dependencies that evade purely quantitative models. The moderate discrimination power (logistic AUC ≈ 0.612) underscores this point: while corruption and age emerge as robust correlates, route choice likely depends on a wider constellation of factors—including local facilitation costs, informal migrant networks, and geopolitical conditions—not included in the current dataset.

Hypothesis 2 finds partial support. Push factors like limited access to services exhibited weak statistical significance, while war/conflict had a negative association with entry via Bulgaria. This aligns with de Valk et al. [

20], who highlight heterogeneity in how different drivers translate into actual route choices, and suggests that economic motives may tilt migrants toward Greece as a gateway to wealthier EU labor markets, while conflict-driven migrants explore alternative or more direct routes. The divergence across push factors highlights the multi-causality of migration, reinforcing the value of multi-level models that bridge individual, household, and institutional scales [

7].

A notable and underexplored feature of our analysis is the substantial “Unknown” governance cluster (2446 cases, approximately 44% of origins), which shows marginal significance (

,

). While partly an artifact of fuzzy matching between IOM survey data and the World Governance Indicators (WGIs), this reflects deeper methodological limitations. Many fragile and conflict-affected states, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo or Iran, are systematically underrepresented in governance datasets due to weak survey infrastructure and reliance on perception-based measures dominated by Global North institutions [

27,

28]. This reliance risks embedding structural biases and echo-chamber effects in governance indices, thereby limiting the explanatory power of cluster-based models. The irony is acute: governance failures are among the most powerful push factors for migration, yet they are least measurable in the contexts where they matter most. Recent updates to WGI [

29] acknowledge these limitations but underscore the need for broader diversification of data inputs, including surveys and administrative data from the Global South, alongside investments in local statistical capacity.

Our findings therefore resonate with a broader debate in migration studies: the tension between model-based quantification and the complex, often opaque realities of migration decision-making [

21]. While corruption provides a theoretically compelling and empirically supported determinant, the limited predictive gains from both GLMs and machine learning models suggest that future research should integrate dynamic variables (real-time border closures and facilitation costs), qualitative narratives of migrant decision-making, and mixed-method approaches. Such triangulation would strengthen both the interpretive and predictive capacity of migration models.

Sert and Erenler [

9] outline various migration theories, supporting our finding that mobility reasons like service deprivation are critical drivers along the Balkan route.

Finally, the temporal context of this study reminds us that migration dynamics are not static. Bulgaria’s rising entry share (38.8%) may reflect not only structural governance affinities but also contingent shifts in EU external border policies, Balkan state practices, and geopolitical crises. Dynamic modeling approaches, such as agent-based simulations or time-varying hazard models, could capture these evolutions more effectively, bridging the gap between static governance indicators and the lived realities of migrants on the move. In sum, this research illuminates corruption’s complex role in shaping route preferences but also exposes the persistent limitations of existing data and models, calling for more inclusive, dynamic, and interdisciplinary approaches to migration analysis.

5.1. Policy Implications

Our results suggest that corruption-aware interventions should be considered across all stages of migration management, but their design must reflect the contextual limitations highlighted by our analysis. In particular, while the data indicate that migrants from high-corruption origins tend to choose routes through governance-similar transit states such as Bulgaria, the explanatory power of this pattern remains modest. Accordingly, our policy reflections focus on governance sensitivity and institutional alignment rather than prescriptive reform.

Origin Stage: Anti-corruption reforms and improved service provision in high-corruption countries (e.g., Syria, 42% of respondents; Afghanistan, 10%) could help mitigate instability and service deficits that act as primary push factors [

8,

16]. However, given the weak predictive strength of our models, these recommendations should be understood as indicative rather than definitive. We emphasize that externally imposed governance reforms may reproduce dependency or elite capture if not accompanied by local ownership. Development cooperation should therefore focus on incremental, capacity-building initiatives aligned with domestic accountability structures.

Transit Stage: Harmonizing border governance in Bulgaria and Greece could reduce facilitation abuses and balance route loads. Gender-sensitive reception measures, given the 88% male dominance in the sample, remain essential [

3]. Nevertheless, we note that our findings cannot quantify the effectiveness of specific enforcement reforms. Over-securitization or excessive anti-corruption policing could inadvertently increase reliance on smuggling networks, as suggested by broader literature on migration control. Thus, this recommendation should be seen as a governance-alignment measure rather than a direct causal inference from our models.

Destination Stage: Low-corruption countries such as Germany (47% intended destination) and Italy (21%) could strengthen integration pathways through legal migration channels and inclusive labor policies [

19]. Our analysis supports this insofar as migrants from high-corruption origins exhibit preferences for destinations with stable governance, but we explicitly caution that the present dataset does not allow for validation of downstream integration outcomes. Hence, we frame this recommendation as a governance-informed observation consistent with, but not proven by, the empirical evidence.

Hence, while corruption-sensitive policies can mitigate forced migration pressures and improve management along the Balkan route, they must be pursued cautiously. Without careful design, external interventions risk reinforcing the very governance failures they aim to address. Future policies should therefore prioritize context-specific, participatory, and multi-scalar approaches that bridge the global–local divide in migration governance.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations of this study warrant careful consideration. First, the reliance on the IOM dataset, while uniquely rich in individual-level information, is constrained by issues of representativeness. Sampling is geographically and temporally concentrated, which may bias findings toward certain nationalities or profiles transiting at that time. Future research should triangulate with other sources (e.g., UNHCR and national asylum data) to ensure robustness across different contexts and time periods. De Valk et al. [

20] highlight the challenges of predicting migration with static data, supporting our call for real-time data integration to address sampling biases in the IOM dataset.

Second, governance clustering using WGI highlights the difficulty of linking individual migrant decisions with macro-level governance scores. The substantial “Unknown” cluster (44% of origins) exposes the fragility of global governance metrics in capturing the realities of fragile or conflict-affected states [

27,

29]. This gap reduces the explanatory power of cluster-based models and underscores the need for diversified data inputs, including administrative records, perception surveys from the Global South, and mixed-method evidence [

28]. Without addressing this structural bias, policy inferences risk over-representing well-documented regions while underestimating governance-driven outflows from data-poor contexts.

Third, the predictive performance of all models remains modest (AUC ≈ 0.51–0.61). This suggests that static predictors such as age, corruption, and push factors, while important, cannot fully account for the situational and contingent nature of migration decisions. As argued by Beyer et al. [

2,

13], migration dynamics are often shaped by shocks, facilitation costs, smuggling networks, and border policies that escape capture in cross-sectional datasets. Future research should explore dynamic designs, including agent-based modeling, event-history analysis, or integration of real-time border monitoring data. Hence, these modest AUC values indicate limited capture of fine-grained predictive patterns, emphasizing the need for dynamic, network-based, and temporal modeling extensions.

Finally, there are risks inherent in external governance-focused interventions. Anti-corruption reforms imposed from outside may exacerbate elite capture, securitization, or stigmatization of migrant populations if not carefully designed. Addressing these risks requires participatory approaches, where reforms are locally owned and co-developed with communities directly affected by corruption and migration pressures.

Taken together, these limitations point toward three directions for future work:

By pursuing these directions, scholars and policymakers can generate more accurate, inclusive, and actionable insights into how governance and corruption shape migration along the Balkan route and beyond.

6. Conclusions

This study empirically demonstrates that corruption and governance quality are central determinants of migration dynamics along the Balkan route, functioning simultaneously as push and structuring factors in migrants’ route selection. Using logistic regression and machine learning models on survey data, the analysis shows that younger migrants are significantly more likely to enter via Bulgaria (≈−0.021, p < 0.001), while economic motivations slightly increase the likelihood of choosing Greece, confirming differentiated routes based on age and economic orientation. Furthermore, the governance cluster analysis reveals that migrants from high-corruption and fragile origin countries disproportionately opt for Bulgaria, hence indicating that institutional similarity and governance affinity, rather than distance alone, play a measurable role in route decisions. Although the models exhibit modest predictive power (McFadden’s R2≈ 0.008; AUC ≈ 0.61), they provide evidence that governance-related factors subtly but consistently shape migration patterns within an adapted gravity model framework.

At the policy level, these empirical insights suggest that governance-sensitive interventions should operate across three stages of migration management. In origin contexts, targeted anti-corruption reforms and improved access to basic services could mitigate key structural push factors. In transit contexts, greater coordination between Bulgaria and Greece could reduce facilitation abuses and strengthen border governance, while gender- and age-sensitive support mechanisms could enhance protection capacities. In destination contexts, countries should continue fostering integration through transparent legal and labor pathways, ensuring that the institutional “pull” of good governance is matched by inclusive reception and opportunity structures.

Nevertheless, several limitations temper these conclusions. The underrepresentation of fragile states in governance datasets and the substantial share of “Unknown” clusters underscore the limitations of global governance indicators in capturing realities of data-poor regions. The modest explanatory and predictive performance of both logistic and machine learning models further reflects the complex, contingent nature of migration decisions, influenced by networks, policy shocks, and smuggling economies beyond the scope of available data. Future research should therefore combine real-time and qualitative data with dynamic modeling approaches to better capture these temporal and contextual dimensions.

In summary, while statistical effects are moderate, the empirical findings affirm that corruption and governance affinities constitute a significant, measurable, and policy-relevant layer of migration decision-making along the Balkan route. A specific feature of our work is reflected in bridging individual motivations with institutional structures in ways that enrich both migration theory and practice.