The Relationship Between Migration Background and Career Benefits in the Lives of Hungarian Mobile Workers in German-Speaking Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

Labour Market Integration of Eastern European Migrant Workers

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Measuring Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

2.3.2. Structure of the Career Benefit Index

2.3.3. Examining the Differences in Occupational Mobility

3. Results

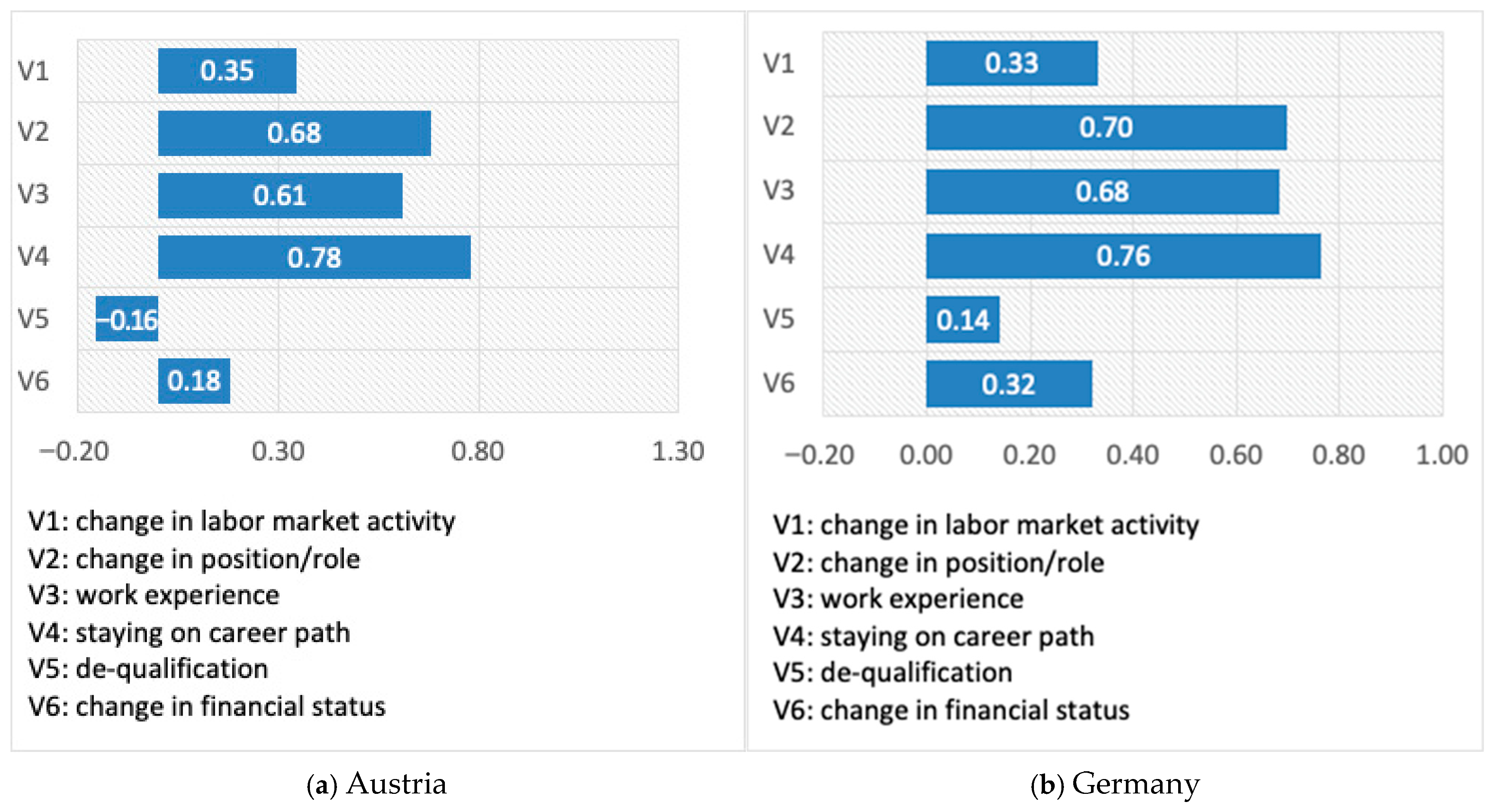

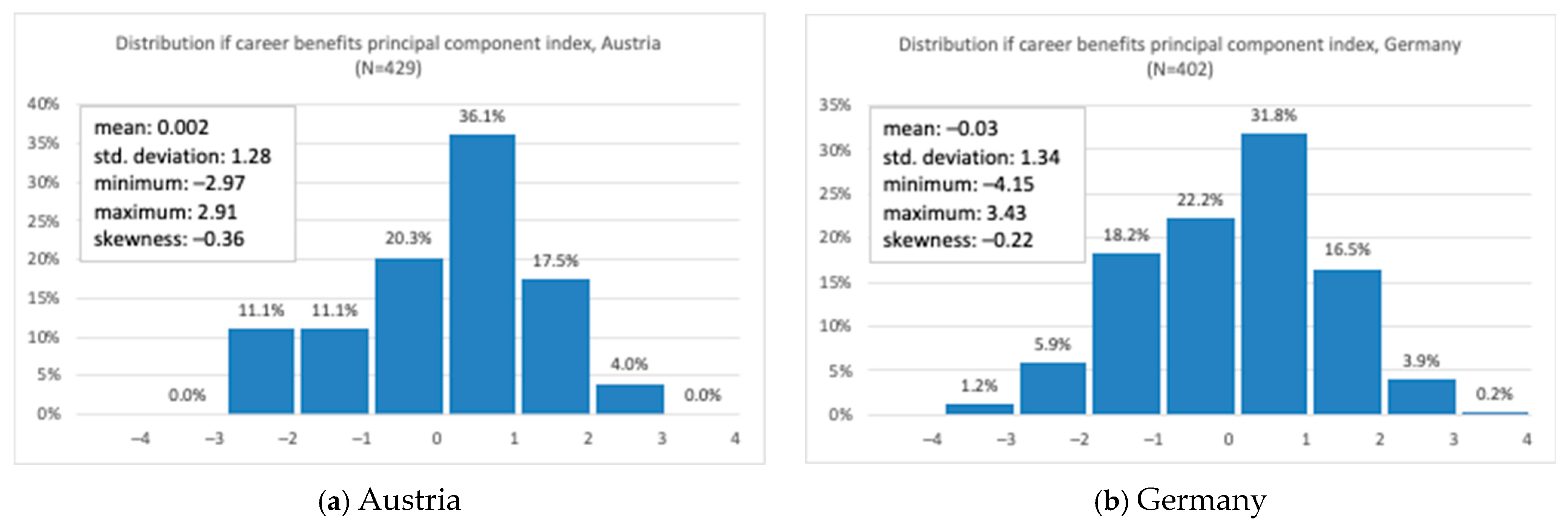

3.1. Composition and Evolution of the Career Benefit Index in the Two Countries

3.2. Demographic Characteristics and Labour Market Skills That Influence Career Benefits

3.2.1. The Role of Educational Attainment

3.2.2. The Role of Demographic Factors

3.2.3. The Role of Language Proficiency

3.2.4. The Role of Other Demographic Factors, Degree of Urbanization in the Origin Country and Duration of Stay

4. Discussion

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable Name | Questionnaire Questions | Variable Values: and Their Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| I. changes in labour market activity | Before you moved, what was your labour market status in Hungary? Indicate the status which gave you the highest income (active status: employed, full-time; self-employed; part-time; casual, contract work; public sector, forced self-employed inactive statuses: retired; student; other inactive earner; homemaker; GYES/GYED; early jobseeker; registered unemployed; not registered unemployed) What is your current labour market status in Austria/Germany? Please indicate the most relevant for your situation. (active status: formal, declared full-time job; formal, declared part-time job; casual work, assignments; working in own business; working without a work contract; working partly or entirely in the black; frontier worker; not working inactive statuses: maternity benefit, childcare benefit, care allowance; registered unemployed without benefits; registered unemployed with benefits; not registered unemployed; studying; not working, at home; other inactive earner; homemaker; retired) | −1: changed from active to inactive 0: no change in activity 1: changed from inactive to active |

| II. change in position | Has your current job changed since your last job in Hungary before you moved? (yes, I work in a higher position/job with more responsibility; yes, I work in a lower position/job with less responsibility; no, I work in the same position/job with similar responsibility; I cannot say | −1: yes, I work in a lower grade/position/job with less responsibility 0: no, I work in the same job/position/job with similar responsibilities; I cannot judge 1: yes, I work in a higher position/position with more responsibility |

| III. recognition of work experience | Are you currently working in Austria/Germany in a field relevant to your work experience in Hungary? (yes/no) | 1: yes −1: no |

| IV. staying on track | Did you work in Hungary in a field relevant to your education before you moved? (yes/no) Are you working in Austria/Germany in a field relevant to your education? (yes/no) | −1: worked in Hungary in a job corresponding to your qualification, but not in Austria/Germany 0: working in Hungary in a job corresponding to your qualification and also in Austria/Germany, 1: or did not work in Hungary in a job corresponding to your qualification and also in Austria/Germany |

| V. de-qualification indicator | What level of education is required for the most lucrative job in Hungary? (1: no qualification required, 2: general education, 3: vocational education, 4: vocational secondary school, 5: secondary school leaving certificate, 6: OKJ qualification, 7: college degree, 8: university degree, 9: doctorate/PhD degree) What level of education is required for the current job that pays the most? (1: no qualification required, 2: general education, 3: vocational education, 4: vocational secondary school, 5: secondary school leaving certificate, 6: OKJ qualification, 7: college degree, 8: university degree, 9: doctorate/PhD degree) | scale: standardized values of the difference between current and Hungarian educational attainment |

| VI. change in financial status | Compared to your life in Hungary, how did your household’s monthly savings change in Austria? −2: Significantly decreased, −1: Somewhat decreased, 0: No change, 1: Somewhat increased, 2: Significantly increased | scale: standardized values of the current scale |

| Variable1 | Variable2 | Pearson’s Correlation | p Value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | 0.1414 | 0.0059 | 379 |

| V1 | V3 | 0.0850 | 0.0986 | 379 |

| V1 | V4 | 0.1236 | 0.0161 | 379 |

| V1 | V5 | −0.0247 | 0.6582 | 323 |

| V1 | V6 | −0.0034 | 0.9483 | 360 |

| V2 | V3 | 0.1548 | 0.0025 | 379 |

| V2 | V4 | 0.3419 | 0.0000 | 379 |

| V2 | V5 | 0.0775 | 0.1646 | 323 |

| V2 | V6 | 0.1281 | 0.0150 | 360 |

| V3 | V4 | 0.2803 | 0.0000 | 379 |

| V3 | V5 | −0.0179 | 0.7481 | 323 |

| V3 | V6 | 0.0292 | 0.5805 | 360 |

| V4 | V5 | −0.0873 | 0.1175 | 323 |

| V4 | V6 | 0.0628 | 0.2345 | 360 |

| V5 | V6 | 0.0481 | 0.3996 | 308 |

| Variable1 | Variable2 | Pearson’s Correlation | p Value | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | V2 | 0.1184 | 0.0273 | 347 |

| V1 | V3 | 0.0939 | 0.0806 | 347 |

| V1 | V4 | 0.0949 | 0.0772 | 347 |

| V1 | V5 | 0.1316 | 0.0238 | 295 |

| V1 | V6 | 0.2062 | 0.0002 | 323 |

| V2 | V3 | 0.2512 | 0.0000 | 359 |

| V2 | V4 | 0.3734 | 0.0000 | 359 |

| V2 | V5 | 0.0371 | 0.5216 | 301 |

| V2 | V6 | 0.1235 | 0.0240 | 334 |

| V3 | V4 | 0.3817 | 0.0000 | 359 |

| V3 | V5 | 0.0063 | 0.9134 | 301 |

| V3 | V6 | 0.0680 | 0.2155 | 334 |

| V4 | V5 | 0.0662 | 0.2517 | 301 |

| V4 | V6 | 0.0700 | 0.2021 | 334 |

| V5 | V6 | 0.0686 | 0.2510 | 282 |

References

- Münz, R. Migration, Labor Markets, and Integration of Migrants: An Overview for Europe; Hamburgisches WeltWirtschaftsInstitut (HWWI): Hamburg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EC) No 883/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Coordination of Social Security Systems (Text with Relevance for the EEA and for Switzerland). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2004/883/oj/eng (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Regulation (EU) No 492/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2011 on Freedom of Movement for Workers within the Union Text with EEA Relevance. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/492/oj/eng (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Eurostat. Population by Country of Citizenship, Age Groups and NUTS 3 Region; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Population by Citizenship/Country of Birth. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/en/statistics/population-and-society/population/population-stock/population-by-citizenship/country-of-birth (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Gödri, I.; Horváth, V. Nemzetközi vándorlás. Demográfiai Portré 2021, 227–250. Available online: https://demografia.hu/kiadvanyokonline/index.php/demografiaiportre/article/view/2835/2725 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Németh, Á.; Göncz, B.; Kohlbacher, J.; Lengyel, G.; Melegh, A.; Németh, Z.; Reeger, U.; Tóth, L. International Migration Patterns in and between Hungary and Austria; Hungarian Demographic Research Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rozhkov, D.; Koczan, Z.; Pinat, M. The Impact of International Migration on Inclusive Growth: A Review. IMF Work. Pap. 2021, 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoyan, R.; Christiansen, L.E.; Dizioli, A.; Ebeke, C.; Ilahi, N.; Ilyina, A.; Mehrez, G.; Qu, H.; Raei, F.; Rhee, A.; et al. Emigration and Its Economic Impact on Eastern Europe. Staff Discuss. Notes 2016, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasani, F. New Approaches to Labour Market Integration of Migrants and Refugees; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2024.

- Gödri, I.; Feleky, G.A. Migration Intentions—Between Dreams and Definite Plans the Impact of Life-Course Events on Different Types of Migration Potential; Hungarian Demographic Research Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S.; Arango, J.; Hugo, G.; Kouaouci, A.; Pellegrino, A.; Taylor, J.E. Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1993, 19, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.L.; Kritz, M.M.; Zlotnik, H. International Migration Systems: A Global Approach. Presented at the Seminar on International Migration Systems, Processes, and Policies, Genting Highlands, Malaysia, 19–23 September 1988; International studies in demography. Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. ISBN 978-0-19-828356-0. [Google Scholar]

- Bauder, H. The International Mobility of Academics: A Labour Market Perspective. Int. Migr. 2015, 53, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borjas, G.J. Economic Theory and International Migration. Int. Migr. Rev. 1989, 23, 457–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjaastad, L.A. The costs and returns of human migration. J. Political Econ. 1962, 70, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortney, J.A. International Migration of Professionals. Popul. Stud. 1970, 24, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, J.; Gaillard, A.M. Introduction: The International Mobility of Brains: Exodus or Circulation? Sci. Technol. Soc. 1997, 2, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hárs, Á.; Simon, D. Külföldi Munkavállalás, Foglalkozásváltás és Szakmaelhagyás. Külgazdaság 2020, 64, 60–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hárs, Á. Elvándorlás, visszavándorlás, bevándorlás: Jelenségek és munkaerő-piaci hatások. In Társadalmi Riport; Kolosi, T., Szelényi, I., Tóth, I.G., Eds.; TÁRKI Társadalomkutatási Intézet Zrt: Budapest, Hungary, 2020; pp. 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hungarian Central Statistical Office, Mikrocenzus 2016—10. Nemzetközi vándorlás; Vukovich, G., Ed.; KSH Népességtudományi Kutató Intézet: Budapest, Hungary, 2016; ISBN 978-963-235-514-6. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/mikrocenzus2016/kotet_10_nemzetkozi_vandorlas (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Mytna Kurekova, L. Theories of Migration: Critical Review in the Context of the EU East-West Flows; CARIM-EUI: Florence, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Piore, M.J. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980; ISBN 978-0-521-22452-9. [Google Scholar]

- Muhirva, J.-M. Funnelling Talents Back to the Source: Can Distance Education Help to Mitigate the Fallouts of Brain Drain in Sub-Saharan Africa? Diversities 2012, 14, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dumont, J.-C.; Martin, J.P.; Spielvogel, G. Women on the Move: The Neglected Gender Dimension of the Brain Drain. SSRN J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.; Clark, N.; Parutis, V. NEW EU MEMBERS? Migrant Workers’ Challenges and Opportunities to UK Trades Unions: A Polish and Lithuanian Case Study; Trades Union Congress (TUC): London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ciupijus, Z. Mobile Central Eastern Europeans in Britain: Successful European Union Citizens and Disadvantaged Labour Migrants? Work. Employ. Soc. 2011, 25, 540–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, K. Are Overqualified Migrants Self-Selected? Evidence from Central and Eastern European Countries. J. Hum. Cap. 2016, 10, 303–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, S.; Eade, J.; Garapich, M. Poles Apart? EU Enlargement and the Labour Market Outcomes of Immigrants in the UK. Int. Migr. 2009, 47, 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, D.; Zweimüller, J. Migration and Labor Market Integration in Europe. J. Econ. Perspect. 2021, 35, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.; Khattab, N.; Manley, D. East versus West? Over-Qualification and Earnings among the UK’s European Migrants. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2015, 41, 196–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favell, A. The New European Migration Laboratory: East Europeans in West European Cities. In Between Mobility and Migration; Scholten, P., Van Ostaijen, M., Eds.; IMISCOE Research Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 263–270. ISBN 978-3-319-77990-4. [Google Scholar]

- Iredale, R. The Migration of Professionals: Theories and Typologies. Int. Migr. 2001, 39, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, S. A Sociology of Globalization; Contemporary societies; W. W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-393-92726-9. [Google Scholar]

- Iredale, R. Gender Immigration Policies and Accreditation: Valuing the Skills of Professional Women Migrants. Geoforum 2005, 36, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, C.; Lubbers, M.; Mühlau, P.; Platt, L. Starting out: New Migrants Socio-Cultural Integration Trajectories in Four European Destinations. Ethnicities 2015, 16, 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liversage, A. Vital Conjunctures, Shifting Horizons: High-Skilled Female Immigrants Looking for Work. Work Employ. Soc. 2009, 23, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liversage, A. Finding a Path: Investigating the Labour Market Trajectories of High-Skilled Immigrants in Denmark. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2009, 35, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voswinkel, S.; Kontos, M. Ungenutzte Kompetenzen. Probleme und Chancen der Beschäftigung Hochqualifizierter Migrantinnen und Migranten. Sozialwissenschaften Berufsprax. 2010, 33, 212–241. [Google Scholar]

- Pietka, E.; Clark, C.; Canton, N. 7. ‘I Know That I Have a University Diploma and I’m Working as a Driver’. Explaining the EU Post-Enlargement Movement of Highly Skilled Polish Migrant Workers to Glasgow: Migration Patterns after EU Enlargement. In Mobility in Transition; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013; pp. 133–154. ISBN 978-90-485-1549-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dalmazzo, A.; Leombruni, R.; Razzolini, T. Anticipation Effects of EU Accession on Immigrants’ Labour Market Outcomes. SSRN J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováts, A.; Papp, A.Z. Patterns of Success amongst Hungarians Living in the UK. Szociológiai Szle. 2016, 26, 95–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, G.; Turk, R.A. The Labor Market Integration of Migrants in Europe: New Evidence from Micro Data. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/11/01/The-Labor-Market-Integration-of-Migrants-in-Europe-New-Evidence-from-Micro-Data-46296 (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Dickey, H.; Drinkwater, S.; Shubin, S. Labour Market and Social Integration of Eastern European Migrants in Scotland and Portugal. Environ. Plan A 2018, 50, 1250–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalikova, N. Segmented Socioeconomic Adaptation of New Eastern European Professionals in the United States. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2018, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tubergen, F.; Kalmijn, M. Destination–Language Proficiency in Cross–National Perspective: A Study of Immigrant Groups in Nine Western Countries. Am. J. Sociol. 2005, 110, 1412–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tubergen, F.; Kalmijn, M. Language Proficiency and Usage Among Immigrants in the Netherlands: Incentives or Opportunities? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2008, 25, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohl, A.-M.; Schittenhelm, K.; Schmidtke, O.; Weiß, A. Cultural Capital during Migration—A Multi-Level Approach for the Empirical Analysis of the Labor Market Integration of Highly Skilled Migrants. Forum Qual. Sozialforschung/Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2006, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohl, A.-M.; Schittenhelm, K.; Schmidtke, O.; Weiss, A. Work in Transition: Cultural Capital and Highly Skilled Migrants’ Passages into the Labour Market; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4426-6873-7. [Google Scholar]

- Balogh, E.; Szvetelszky, Z.; Nagy, J.T.; Tóth, M.F.; Csanády, M. A Kis-És Kisiskolás Gyermeket Gondozó Magas Iskolai Végzettséggel Rendelkező Magyar Feleségek Integrációs Kihívásai a Bécsi Munkaerőpiacon. In Kutatás, képzés, közösség: A Károli Gáspár Református Egyetem Szociológia Tanszékének jubileumi tanulmánykötete; L’Harmattan: Budapest, Hungary, 2024; ISBN 978-615-5961-99-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nohl, A.-M.; Schittenhelm, K.; Schmidtke, O.; Weiß, A. (Eds.) Kulturelles Kapital in der Migration; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2010; ISBN 978-3-531-16437-3. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, P.; Feng, Z.; Gayle, V. A New Look at Family Migration and Women’s Employment Status. J. Marriage Fam. 2009, 71, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.K. International Migration of Highly Educated, Stay-at-Home Mothers: The Case of the United Kingdom. Turk. Stud. 2021, 22, 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Erlinghagen, M. Love in Motion: Migration Patterns of Internationally Mobile Couples. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shihadeh, E.S. The Prevalence of Husband-Centered Migration: Employment Consequences for Married Mothers. J. Marriage Fam. 1991, 53, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhlich, A. Migration and Social Pathways; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-8474-2118-4. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, J.; Sweetman, A. Immigrant Earnings: Age at Immigration Matters. Can. J. Econ. 2001, 34, 1066–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R. Immigrant Earnings Adjustment: The Impact of Age at Migration. Aust. Econ. Pap. 2003, 42, 292–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.M.; Andersson, L.; Hammarstedt, M. Does Age Matter for Employability? A Field Experiment on Ageism in the Swedish Labour Market. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2012, 19, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, S.; Johansson, P.; Langenskiöld, S. What Is the Right Profile for Getting a Job? A Stated Choice Experiment of the Recruitment Process. Empir. Econ. 2017, 53, 803–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogh, E.; Mikó, F.; Csanády, M. Karrierhaszon-dilemmák: Magyar nők lehetőségei az osztrák munkaerőpiacon. Szociológiai Szle. 2022, 32, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, J.T.; Balogh, E.; Cziráki, K.T.; Szvetelszky, Z.; Csanády, M.T. A Migráns Személyek Karrierpályájának Mérési Lehetősége: A Karrierhaszon-Mutató. Szociológiai Szle. 2025, 35, 60–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csugány, J.; Kozák, A. Regionális Munkaerőpiaci Problémák—A Külföldi Munkavállalás Súlyosbítja-e Az Északkeleti Régiók Helyzetét Magyarországon? TéT 2018, 32, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpek, B.L.; Tésits, R. A Foglalkoztathatóság Térszerkezeti és Települési Dimenziói Magyarországon. Területi Stat. 2019, 59, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Population on 1 January by Age Group, Sex and Country of Birth; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- DESTATIS. Foreign Population by Place of Birth and Selected Citizenships. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Population/Migration-Integration/Tables/foreigner-place-of-birth.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Jestl, S.; Landesmann, M.; Leitner, S.M. Migrants and Natives in EU Labour Markets: Mobility and Job-Skill Mismatch Patterns; The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw): Vienna, Vienna, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, R.; Bechara, P.; Vonnahme, C. Occupational Mobility in Europe: Extent, Determinants and Consequences. Economist 2019, 168, 79–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, F.; Le, S.; Pagès, J. Exploratory Multivariate Analysis by Example Using R, 2nd ed.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-429-22543-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, J.M.; Freeny, A.E.; Heiberger, R.M. Analysis of Variance; Designed Experiments. In Statistical Models in S; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J. Are Immigrants the Most Skilled US Computer and Engineering Workers? J. Labor Econ. 2015, 33, S39–S77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, I.; Weißmann, M. Immigrants’ Initial Steps in Germany and Their Later Economic Success. Adv. Life Course Res. 2013, 18, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Kristen, C.; Mühlau, P. Educational Selectivity and Immigrants’ Labour Market Performance in Europe. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2022, 38, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward-Warmedinger, M.; Macchiarelli, C. Transitions in Labour Market Status in EU Labour Markets. IZA J. Labor Stud. 2014, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolchev, C. ‘Dances with Daffodils’: Life as a Flower-Picker in Southwest England. Work Employ. Soc. 2022, 36, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtovaara, H.; Jyrkinen, M. Skilled Migrant Women’s Experiences of the Job Search Process. NJWLS 2021, 11, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieckoff, B.; Sprengholz, M. The Labor Market Integration of Immigrant Women in Europe: Context, Theory, and Evidence. SN Soc. Sci. 2021, 1, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achouche, N. The Motherhood Penalty of Immigrants in France: Comparing the Motherhood Wage Penalty of Immigrants from Europe, the Maghreb, and Sub-Sahara with Native-Born French Women. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 748826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballarino, G.; Panichella, N. The Occupational Integration of Migrant Women in Western European Labour Markets. Acta Sociol. 2018, 61, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, S. The Differences in Quality of Employment Between Highly Skilled Migrant and Non-Migrant Women and Men. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 5, 60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, P.; Graham, E.; Yeoh, B. Editiorial Introduction: Labour Migration and the Family in Asia. Int. J. Popul. Geogr. 2003, 9, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melegh, A.; Kovács, É.; Gödri, I. (Eds.) “Azt Hittem célt Tévesztettem”: A Bevándorló nők Élettörténeti Perspektívái, Integrációja és a Bevándorlókkal Kapcsolatos Attitűdök Nyolc Európai Országban; Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Népességtudományi Kutatóintézetének kutatási jelentései; KSH Népességtudományi Kutató Intézet: Budapest, Hungary, 2010; ISBN 978-963-9597-17-4. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, H. Migration, language and integration; AKI Research Review, 4; Social Science Research Center Berlin (WZB): Berlin, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.; Lever, J.; Thompson, A. The Labour Market Mobility of Polish Migrants: A Comparative Study of Three Regions in South Wales, UK. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2014, 3, 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Adsera, A.; Pytlikova, M. The Role of Language in Shaping International Migration. IZA J. Eur. Labor Stud. 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubanov-Boskovic, S.; Tintori, G.; Biagi, F. Gaps in the EU Labour Market Participation Rates: An Intersectional Assessment of the Role of Gender and Migrant Status; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cools, S.; Markussen, S.; Strøm, M. Children and Careers: How Family Size Affects Parents’ Labor Market Outcomes in the Long Run. Demography 2017, 54, 1773–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, J.; Wood, J.; Neels, K. Path-Dependencies in Employment Trajectories Around Motherhood: Comparing Native Versus Second-Generation Migrant Women in Belgium. Int. Migr. Integr. 2023, 24, 281–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constant, A.F.; Massey, D.S. Self-Selection, Earnings, and Out-Migration: A Longitudinal Study of Immigrants to Germany. J. Popul. Econ. 2002, 16, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liapi, M.; Vouyioukas, A. Policy Gaps in Integration and Reskilling Strategies of Migrant Women. Soc. Cohes. Dev. 2016, 4, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdankhoo, S.; Abkhezr, P.; Mcauliffe, D.; McMahon, M. Migrant Women Navigating the Intersection of Gender, Migration, and Career Development: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Vocat. Behav. 2025, 157, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijwaard, G.E.; Schluter, C.; Wahba, J. Does Unemployment Cause Return Migration? ESRC Centre for Population Change: Southampton, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, 2nd ed.; Midway reprints; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983; ISBN 978-0-226-04109-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswick, B.R. The Effect of Americanization on the Earnings of Foreign-Born Men. J. Political Econ. 1978, 86, 897–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiswick, B.R.; Miller, P.W. The Endogeneity between Language and Earnings: International Analyses. J. Labor Econ. 1995, 13, 246–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, H. Does the “New” Immigration Require a “New” Theory of Intergenerational Integration? Int. Migr. Rev. 2004, 38, 1126–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyar-Busto, M.; Mato Díaz, F.J.; Gutiérrez, R. Immigrants’ Educational Credentials Leading to Employment Outcomes: The Role Played by Language Skills. RIO 2020, 23, 167–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frattini, T.; Cugini, G. The Labour Market Disparities of Second-Generation Immigrants. Available online: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/labour-market-disparities-second-generation-immigrants (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Berbée, P.; Stuhler, J. The Integration of Migrants in the German Labor Market: Evidence over 50 Years. Econ. Policy 2023, 40, 481–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzi, M.; Kahanec, M.; Mýtna Kureková, L. The Impact of Immigration and Integration Policies on Immigrant-Native Labour Market Hierarchies. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2023, 49, 4169–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.; Donato, S. Women Migrant Workers’ (WMWS) Deskilling. Open Res. Eur. 2025, 4, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmone, I.; Frattini, T. The Labour Market Disadvantages for Immigrant Women. Available online: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/labour-market-disadvantages-immigrant-women (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Simmel, G. The Sociology of Secrecy and of Secret Societies. Am. J. Sociol. 1906, 11, 441–498. [Google Scholar]

- Gambetta, D. (Ed.) Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations; Basil Blackwell: New York, NY, USA; Oxford, UK, 1988; ISBN 978-0-631-15506-5. [Google Scholar]

- Ette, A. Migration and Refugee Policies in Germany: New European Limits of Control? 1st ed.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2017; ISBN 978-3-8474-1077-5. [Google Scholar]

- Brydsten, A.; Baranowska-Rataj, A. Intergenerational Interdependence of Labour Market Careers. Adv. Life Course Res. 2022, 54, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable Name | For Austria (N = 429) | For Germany (N = 402) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Values N (%) | N (%) or Mean (SD) | Missing Values N (%) | N (%) or Mean (SD) | |

| Sex | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Male | 193 (45%) | 173 (43%) | ||

| Female | 236 (55%) | 229 (57%) | ||

| Age | 0 (0) | 43.8 (12.10) | 0 (0) | 43.48 (11.03) |

| Family status | 2 (0.5%) | 4 (1%) | ||

| Single | 109 (25%) | 97 (24%) | ||

| In partnership | 318 (75%) | 301 (76%) | ||

| Disposal of children | 8 (2%) | 11 (3%) | ||

| Disposal | 180 (43%) | 153 (39%) | ||

| Not disposal | 242 (57%) | 238 (61%) | ||

| Level of German language proficiency | 20 (5%) | 36 (9%) | ||

| Basic (A1–A2) | 143 (35%) | 155 (42%) | ||

| Intermediate (B1–B2) | 178 (43%) | 155 (42%) | ||

| Upper level (C1–C2) | 89 (22%) | 56 (16%) | ||

| Education level | 1 (0.2%) | 4 (1%) | ||

| Primary | 96 (22%) | 124 (31%) | ||

| Secondary | 246 (57%) | 185 (47%) | ||

| Higher | 86 (20%) | 89 (22%) | ||

| Type of residence in Hungary | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Village/municipality (Control) | 127 (30%) | 79 (20%) | ||

| City | 196 (45%) | 220 (54%) | ||

| Capital city | 106 (25%) | 104 (26%) | ||

| Length of migration | 7.9 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 7.1 (3.5) | |

| Country | Index | Average | Standard Deviation | LCI | UCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | Z-score index | 0.2117 | 0.1706 | −0.1177 | 0.5453 |

| Austria | Principal component index | −0.0036 | 0.0494 | −0.0963 | 0.0954 |

| Germany | Z-score index | 0.1696 | 0.1530 | −0.1331 | 0.4673 |

| Germany | Principal component index | 0.0005 | 0.0482 | −0.0901 | 0.0943 |

| Austria | Germany | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 0.162 *** | 0.162 *** | 0.221 ** | 0.210 *** | 0.185 *** | 0.151 * |

| Female (Control) | ||||||

| Age | −0.242 *** | −0.307 *** | −0.305 *** | −0.109 * | −0.160 ** | −0.169 ** |

| Level of German language proficiency | ||||||

| Basic level (A1–A2) | −0.087 | −0.036 | 0.004 | −0.081 | −0.059 | −0.132 |

| Intermediate (B1–B2) (Control) | ||||||

| Upper level (C1–C2) | 0.219 *** | 0.198 *** | 0.222 ** | 0.119 * | −0.096 | −0.093 |

| Education level | ||||||

| Primary | 0.058 | 0.068 | 0.471 | −0.066 | −0.052 | −0.064 |

| Secondary (Control) | ||||||

| Higher | −0.075 | −0.066 | 0.151 | −0.039 | −0.041 | −0.029 |

| Length of migration | 0.155 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.112 * | 0.104 | ||

| Type of residence in Hungary | ||||||

| Village/municipality (Control) | ||||||

| City | 0.020 | 0.020 | −0.016 | −0.013 | ||

| Capital city | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.027 | 0.023 | ||

| Family status | ||||||

| Single | −0.038 | −0.016 | 0.120 * | 0.181 ** | ||

| Partnership (Control) | ||||||

| Disposal of children | ||||||

| Not disposal | 0.089 | 0.094 | 0.004 | 0.009 | ||

| Disposal (Control) | ||||||

| Male X Basic level (A1–A2) | −0.061 | 0.134 | ||||

| Male X Upper level (C1–C2) | −0.034 | 0.007 | ||||

| Male X Single | −0.039 | −0.097 | ||||

| R2 | 0.183 | 0.208 | 0.211 | 0.087 | 0.112 | 0.122 |

| R2 change | 0.183 | 0.025 | 0.002 | 0.087 | 0.025 | 0.010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagy, J.T.; Balogh, E.; Cziráki, K.T.; Ábrahám, J.S.; Szvetelszky, Z. The Relationship Between Migration Background and Career Benefits in the Lives of Hungarian Mobile Workers in German-Speaking Countries. World 2025, 6, 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040146

Nagy JT, Balogh E, Cziráki KT, Ábrahám JS, Szvetelszky Z. The Relationship Between Migration Background and Career Benefits in the Lives of Hungarian Mobile Workers in German-Speaking Countries. World. 2025; 6(4):146. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040146

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagy, Judit T., Eszter Balogh, Károly Tamás Cziráki, Jázmin Szonja Ábrahám, and Zsuzsanna Szvetelszky. 2025. "The Relationship Between Migration Background and Career Benefits in the Lives of Hungarian Mobile Workers in German-Speaking Countries" World 6, no. 4: 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040146

APA StyleNagy, J. T., Balogh, E., Cziráki, K. T., Ábrahám, J. S., & Szvetelszky, Z. (2025). The Relationship Between Migration Background and Career Benefits in the Lives of Hungarian Mobile Workers in German-Speaking Countries. World, 6(4), 146. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040146