Gendered Power in Climate Adaptation: A Systematic Review of Pastoralist Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

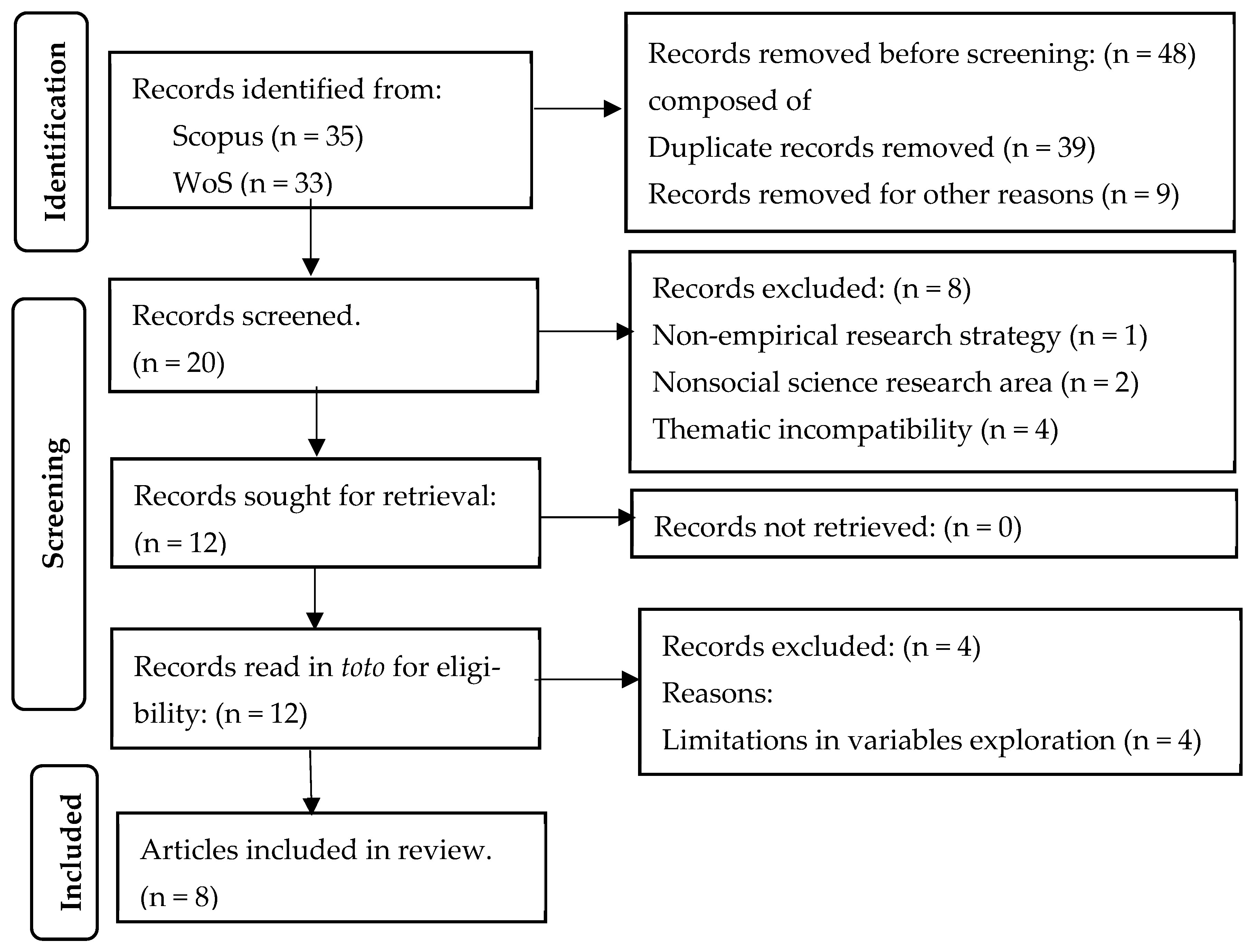

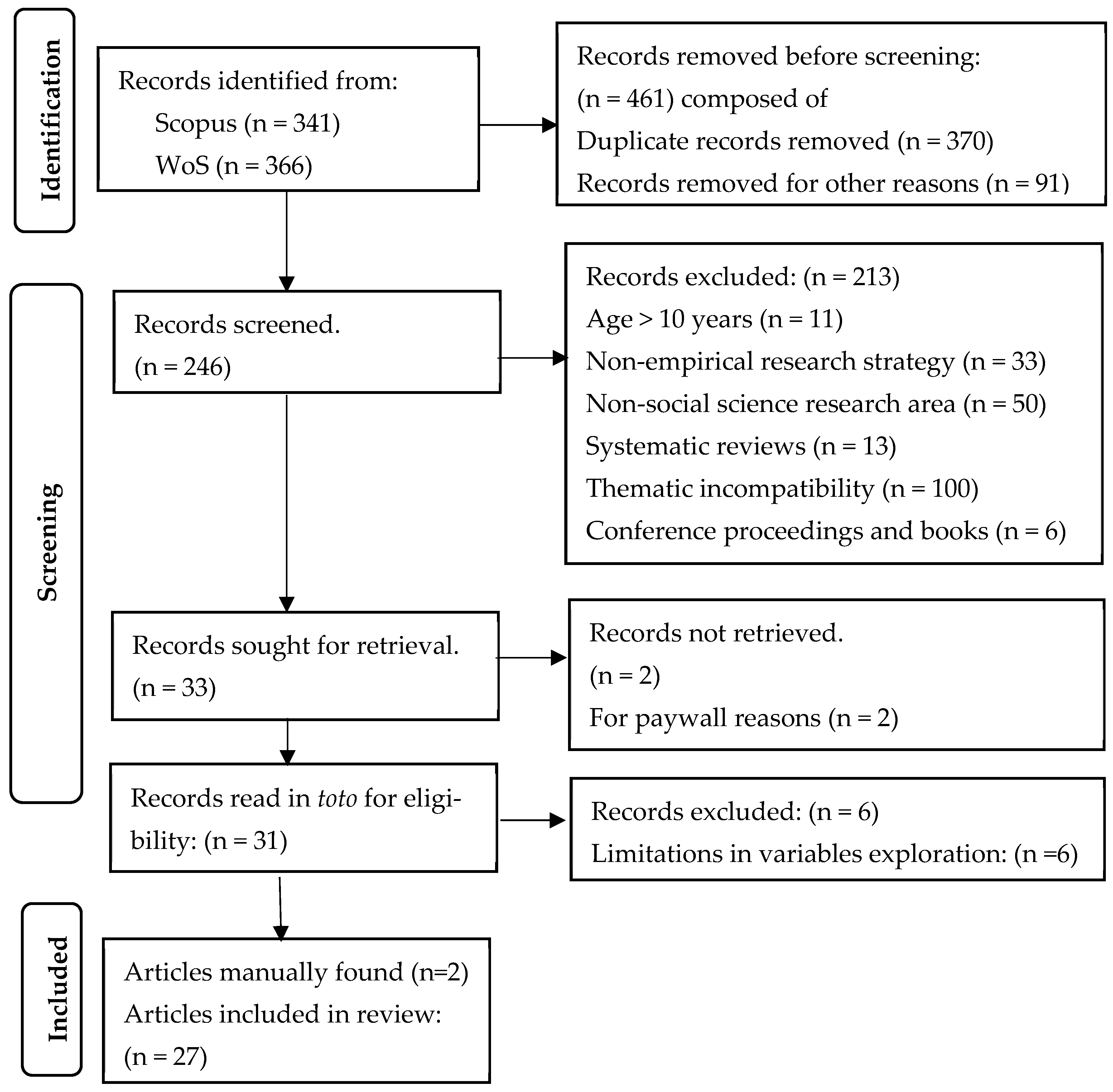

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection

2.2. Data Extraction and Study Characteristics

2.3. Quality Appraisal

2.4. Synthesis Without Meta-Analysis Approach

2.5. Synthesis Process

2.6. Data Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis Across Thematic Domains

3.1.1. Labour and Work Roles

3.1.2. Access to and Control over Resources

| Study | Region | Domain | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Kenya | Social differentiation | Social differentiation, adaptation pathways, land tenure |

| [5] | Kenya | Kinship networks | Kinship networks, gendered resource sharing, drought coping strategies |

| [16] | Kyrgyzstan | Resource access | Gendered views on climate impacts on resources and rural livelihoods. |

| [21] | India | Social contruction of resources accessibility | Access is shaped by social norms and conjugal relations. gendered labour is shaped by social norms and conjugal relations |

| [30] | Namibia | Covert networks | Covert networks, market strategies, gendered livestock management |

| [34] | Colombia | Communal resource governance | Use of decentralised political systems suited to transhumant pastoralism, allowing clans autonomy over extended territories for herd management. |

| [35] | Ethiopia | Land tenure insecurity | Land tenure insecurity, microfinance impacts, gendered vulnerability |

| [36] | Tunisia | Gendered labour | Gender shaped resource access, climate exposure, and adaptive capacity. |

| [41] | Kenya | Enclosure impacts | Enclosure impacts, women’s networks, land privatisation effects |

| [42] | Tanzania | Gender inequalities in resource access | Gender inequalities in resource access, climate information utilisation |

| [47] | Benin | Perceived climate risk and adaptive capacity | Women smallholders saw climate risks but lacked mobility and land to adapt. |

| [48] | Kenya | Community resource governance | Quotas raised women’s presence but left key decisions in male hands. |

| [51] | Tanzania | Resource scarcity and gender roles | Drought reduced water and fuel access, increasing women’s burdens and restricting mobility |

| [50] | India | Place-based vulnerability and limitations to resources access | Gendered vulnerabilities are deeply linked to place-based factors such as geography, caste, and class, especially for women. |

3.1.3. Decision-Making Power

3.1.4. Knowledge Systems and Networks

3.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPRI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SWiM | Synthesis Without Meta-analysis |

| SES | Socio-Ecological Systems |

References

- Ng’ang’a, T.W.; Crane, T.A. Social differentiation in climate change adaptation: One community, multiple pathways in transitioning Kenyan pastoralism. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 114, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmeier, K. Social-Ecological Transformation: Reconnecting Society and Nature; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.R. Resilient livelihoods in an era of global transformation. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 64, 102155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Pastoralism—Making Variability Work; FAO Animal Production and Health; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.; Lawson, E.T.; Raditloaneng, W.N.; Solomon, D.; Angula, M.N. Gendered vulnerabilities to climate change: Insights from the semi-arid regions of Africa and Asia. Clim. Dev. 2017, 11, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertz, O.; Rasmussen, K.; Vang Rasmussen, L. Weather and resource information as tools for dealing with farmer–pastoralist conflicts in the Sahel. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2016, 7, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Ingredients of famine analysis: Availability and entitlements. Q. J. Econ. 1981, 96, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, E.R. Between structure and agency: Livelihoods and adaptation in Ghana’s Central Region. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbacha, A.E.; Kjosavik, D.J. The dynamics of gender relations under recurrent drought conditions: A study of Borana pastoralists in southern Ethiopia. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Social capital, collective action, and adaptation to climate change. Econ. Geogr. 2003, 79, 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. Gender and forest conservation: The impact of women’s participation in community forest governance. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2785–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Change 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerneck, A. What about gender in climate change? Twelve feminist lessons from development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmhirst, R. Feminist political ecology. In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology; Perreault, T., Bridge, G., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 519–530. [Google Scholar]

- Galwab, A.M.; Koech, O.K.; Wasonga, O.V.; Kironchi, G. Gender-differentiated roles and perceptions on climate variability among pastoralist and agro-pastoralist communities in Marsabit, Kenya. Nomad. Peoples 2024, 28, 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarov, A.; Kulikov, M.; Sidle, R.C.; Zaginaev, V. Climate change and its impact on natural resources and rural livelihoods: Gendered perspectives from Naryn, Kyrgyzstan. Climate 2025, 13, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djoudi, H.; Locatelli, B.; Vaast, C.; Asher, K.; Brockhaus, M.; Basnett Sijapati, B. Beyond dichotomies: Gender and intersecting inequalities in climate change studies. Ambio 2016, 45, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N. From abandonment to autonomy: Gendered strategies for coping with climate change, Isiolo County, Kenya. Geoforum 2019, 102, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigil, S. Towards a feminist political ecology of migration in a changing climate. Geoforum 2024, 155, 104076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omolo, N.; Mafongoya, P.L. Gender, social capital and adaptive capacity to climate variability: A case of pastoralists in arid and semi-arid regions in Kenya. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2019, 11, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubramanian, K.; Ramnarain, S. Gender and adaptation to climate change: Perspectives from a pastoral community in Gujarat, India. Dev. Change 2018, 49, 1580–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.R.; Thompson, M.C. Gender and climate change adaptation in agrarian settings: Current thinking, new directions, and research frontiers. Geogr. Compass 2014, 8, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, A. Women’s use of indigenous knowledge systems to cope with climate change. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2019, 6, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, S.H.; Nightingale, A.J.; Eakin, H. Reframing adaptation: The political nature of climate change adaptation. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangui, E.E.; Smucker, T.A. Gendered opportunities and constraints to scaling up: A case study of spontaneous adaptation in a pastoralist community in Mwanga District, Tanzania. Clim. Dev. 2018, 10, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; McKenzie, J.E.; Sowden, A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Brennan, S.E.; Ellis, S.; Hartmann-Boyce, J.; Ryan, R.; Shepperd, S.; Thomas, J.; et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ 2020, 368, l6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, O.F. Adapting Gambian women livestock farmers’ roles in food production to climate change. J. Food Agric. Soc. 2017, 5, 56–66. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hebis:34-2017082853363 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Balehey, S.; Tesfay, G.; Balehegn, M. Traditional gender inequalities limit pastoral women’s opportunities for adaptation to climate change: Evidence from the Afar pastoralists of Ethiopia. Pastoralism 2018, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, A.; Meeks, G.; Bharti, N.; Jakurama, J.; Matundu, J.; Jones, J.H. Opportunities and constraints in women’s resource security amid climate change: A case study of arid-living Namibian agro-pastoralists. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2021, 33, e23633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presler-Marshall, E.; Yadete, W.; Jones, N.A.; Gebreyehu, Y. Making the “unthinkable” thinkable: Fostering sustainable development for youth in Ethiopia’s lowlands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecca, F.; Saima, S. Pastoralism and women’s role in food security in the Ethiopian Somali region. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, A. Who would watch the animals? Gendered knowledge and expert performance among Andean pastoralists. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2021, 43, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forero, O.A.; Rúa Bustamante, C.; Zambrano Ortiz, J.R. Beyond animal husbandry: The role of herders among the Wayuu of Colombia. Hum. Ecol. 2023, 51, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihiretu, A.; Okoyo, E.N.; Lemma, T. Determinants of adaptation choices to climate change in agro-pastoral dry lands of Northeastern Amhara, Ethiopia. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2019, 5, 1636548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, D.; Baruah, B. “Even the goats feel the heat:” Gender, livestock rearing, rangeland cultivation, and climate change adaptation in Tunisia. Clim. Dev. 2024, 16, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeda, A.Z.; Maleko, D.D.; Mtengeti, E.J. Socio-economic and ecological dimensions of climate variability and change for agro-pastoral communities in central Tanzania. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2013, 25, 209. Available online: https://www.lrrd.org/lrrd25/12/sang25209.htm (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Sandstrom, S.; Strapasson, A. Socio-environmental assessment of gender equality, pastoralism, agriculture and climate information in rural communities of Northern Tanzania. J. Gend. Agric. Food Secur. 2017, 2, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, M.; Muhanguzi, F.K.; Boonabaana, B. The effects of climate change on gender roles among agro-pastoral farmers in Nabilatuk District, Karamoja subregion, NorthEastern Uganda. Front. Hum. Dyn. 2023, 5, 1092241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catley, A.; Arasio, R.L.; Hopkins, C. Using participatory epidemiology to investigate women’s knowledge on the seasonality and causes of acute malnutrition in Karamoja, Uganda. Pastoralism 2023, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archambault, C.S. Re-creating the commons and re-configuring Maasai women’s roles on the rangelands in the face of fragmentation. Int. J. Commons 2016, 10, 728–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.E.; Bruyere, B.L.; Yasin, A.; Lenaiyasa, E.; Lolemu, A. The good life in the face of climate change: Understanding complexities of a well-being framework through the experience of pastoral women. J. Dev. Stud. 2021, 57, 1120–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aregu, L.; Darnhofer, I.; Tegegne, A.; Hoekstra, D.; Wurzinger, M. The impact of gender-blindness on social-ecological resilience: The case of a communal pasture in the highlands of Ethiopia. Ambio 2016, 45, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opiyo, F.; Wasonga, O.V.; Nyangito, M.M.; Mureithi, S.M.; Obando, J.; Munang, R. Determinants of perceptions of climate change and adaptation among Turkana pastoralists in northwestern Kenya. Clim. Dev. 2016, 8, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, S.E.; Bruyere, B.L.; Solomon, J.N.; Powlen, K.A.; Yasin, A.; Lenaiyasa, E.; Lolemu, A. Pastoral coping and adaptation climate change strategies: Implications for women’s well-being. J. Arid Environ. 2022, 197, 104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebhuoma, E.E.; Donkor, F.K.; Ebhuoma, O.O.; Leonard, L.; Tantoh, H.B. Subsistence farmers’ differential vulnerability to drought in Mpumalanga province, South Africa: Under the political ecology spotlight. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1792155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimon, E.; Toukourou, Y.; Egah, J.; Assani Seidou, A.; Diogo, R.V.C.; Alkoiret Traore, I. Determinants of women small ruminant farmers’ perceptions of climate change impact in Northern Benin. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2025, 65, AN23427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillos, T. Women’s participation in environmental decision-making: Quasi-experimental evidence from northern Kenya. World Dev. 2018, 108, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunow, A.; Muthama, N.J.; Mwalichi, I.J.; Josiah, K. Comparative analysis of the role of gender in climate change adaptation between Kajiado and Kiambu County, Kenya. J. Clim. Change Sustain. 2019, 3, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadwal, S.; Sharma, G.; Gorti, G.; Sen, S.M. Livelihoods, gender and climate change in the Eastern Himalayas. Environ. Dev. 2019, 31, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtupile, E.E.; Liwenga, E.T. Adaptation to climate change and variability by gender in agro-pastoral communities of Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emongor, A.O.; Bikketi, R.; Were, E. Assessment of gender and innovations in climate-smart agriculture for food and nutrition security in Kenya: A case of Kalii watershed. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2017, 13, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camfield, L.; Leavy, J.; Endale, S.; Tefera, T. People who once had 40 cattle are left only with fences: Coping with persistent drought in Awash, Ethiopia. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 32, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, E.R. Properties and projects: Reconciling resilience and transformation for adaptation and development. World Dev. 2019, 122, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, W.; Beyene, F. The impact of climate change on pastoral production systems: A study of climate variability and household adaptation strategies in southern Ethiopian rangelands. In WIDER Working Paper, 2014/028; United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Vulnerability. Glob. Environ. Change 2006, 16, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Region | Domain | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Kenya | Adaptation practices. | Gendered adaptation practices are shaped by diverse, socially-embedded labour roles, which influence responses to climate stress. |

| [5] | India and Africa | Gendered labour and caste | Women undertook labour-intensive adaptation while control stayed with dominant caste men. |

| [9] | Ethiopia | Household labour division. | Women managed livestock care but only men had influence over adaptation decisions. |

| [20] | Kenya | Kinship-based labour reallocation | Women used informal work-sharing during droughts, taking on extra provisioning roles. |

| [21] | India | Livelihood transitions and gender | Women joined cooperatives, gaining income but working longer hours. |

| [25] | Tanzania | Gendered adaptation practices | Adaptation increased women’s labour through collective and household roles. |

| [28] | Gambia | Youth climate innovation and roles | Young women led climate innovation but remained marginal in formal institutions. |

| [30] | Namibia | Goat markets and informal economies | Women established covert markets, increasing agency within informal systems. |

| [31] | Ethiopia | Labour burdens among adolescents | Girls were withdrawn from school to help with domestic tasks during climate stress. |

| [32] | Ethiopia | Participatory work roles | Women joined research efforts but had no implementation authority. |

| [33] | Peru | Pastoralist labour and wellbeing | Women’s labour rose affecting their individual and society level participation. |

| [36] | Tunisia | Labour shifts and environmental interventions | Women’s roles expanded through ecological restoration efforts |

| [37] | Tanzania | Adaptation pressures on work roles | Women travelled farther for water and fuelwood during stress. |

| [38] | Kenya | Environmental committees and gender | Women attended more meetings, but men retained decision-making authority. |

| [40] | Uganda | Labour redistribution | Women’s labour intensified as livestock farming became less viable. Poorer households rely heavily on diversified livelihood activities such as manual wage labour, often requiring considerable effort for limited income |

| [41] | Kenya | Drought responses and household roles | Climate shocks shifted household labour, burdening women disproportionately. |

| Study | Region | Domain | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1] | Kenya | Intersectional moderators of decision-making power | Decision-making powers are unevenly distributed along social lines such as gender and wealth, affecting who can influence adaptation strategies and outcomes |

| [9] | Ethiopia | Decision-making outcomes | Women’s participation in decision-making is often restricted by social norms, but when they gain income or information, their agency and influence within households improve. |

| [28] | Gambia | Male migration patterns | Male migration patterns cause women’s leadership in de facto settings but with significant limitations. Males accessibility to digital adaptation tools influential for decisions. |

| [29] | Ethiopia | Influences of traditional social structures | Customs like Absuma marriage, widow inheritance reinforce male dominance in decisions. |

| [30] | Namibia | Covert networks | Covert networks, market strategies, gendered livestock management |

| [31] | Ethiopia | Youth agency | Youth agency, gendered labour burdens, digital innovation |

| [33] | Peru | Herding protocols | Women in charge of all Alpaca herding day to day care but excluded from meetings, research and decision structures on the livestock. |

| [34] | Colombia | Decision-making procedures | Decisions related to animal husbandry, trade, sales, or sacrifice conform to social norms and reciprocity within the clan system, emphasising cultural values over purely economic considerations |

| [35] | Ethiopia | Inclusion and exclusion in decision formalities | Women’s participation in decision-making is minimal; they are often represented by their husbands in assemblies, which limits their voice and influence in crafting rules and management decisions |

| [40] | Uganda | Seasonality of malnutrition | Seasonality of malnutrition, women’s workload |

| [42] | Kenya | Choices in livelihood decisions | Women with alternative income-generating activities can increase their power over household decisions while allowing men to continue their traditional pastoralist roles. |

| [43] | Kenya | Cultural decision-making norms | Social-cultural norms and customary laws hinder women’s active and effective participation in climate change adaptation decisions. |

| [44] | Benin | Enhancers and limiters of decision-making | Decision-making regarding climate change adaptation is influenced by access to credit, social networks, and resource availability. Adaptation is also a political process involving adjustments to drought and conflict. |

| [48] | Kenya | Decision-making strategies | Women often balance immediate survival needs with long-term sustainability, employing adaptive strategies despite limited formal decision-making power within patriarchal systems. |

| [51] | South Africa | Social differences | Power relations and social differences (e.g., gender, local vs. non-local status) affect decision-making in resource access and livestock care. |

| [52] | India | Internal vs external decision-making norms | Traditional institutions like the Dzumsa exclude women from decision-making meetings, reinforcing male dominance in economic positions. Women can only advise male partners but have limited voice in meetings. |

| Study | Region | Knowledge Domain | Gendered Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | Kenya | Marital negotiations and adaptation | Women used marital strategies to influence household adaptation decisions. |

| [16] | Kyrgyzstan | Pasture use, governance participation | Women and youth excluded from pasture decision spaces |

| [21] | India | Caste and adaptation planning | Maldhari women excluded from adaptation forums due to caste and gender. |

| [28] | Gambia | Youth innovation program | Program expanded girls’ and boys’ climate knowledge and digital inclusion |

| [29] | Ethiopia | Microfinance and household investment | Microfinance improved women’s liquidity but did not shift intra-household decision-making. |

| [30] | Namibia | Market intelligence sharing | Women used covert channels to circulate livestock pricing data |

| [31] | Ethiopia | Youth digital access | Boys accessed information digitally; girls relied on social networks |

| [33] | Peru | Forage knowledge, institutional exclusion | Male leaders consulted, sidelining women’s expertise |

| [34] | Colombia | Herd migration, cultural knowledge | Pastoralism depends on traditional knowledge, skills, and strategies adapted to local environmental contexts. Women maintain kinship-based adaptation and knowledge transmission |

| [36] | Tunisia | Rangeland and livestock decision-making | Women’s participation in communal rangeland committees was limited and often tokenistic. |

| [37] | Tanzania | Informal adaptation networks | Women exchanged drought knowledge through local groups |

| [40] | Uganda | Child malnutrition, seasonal knowledge | Women used nuanced indigenous classifications and causal reasoning |

| [41] | Kenya | Climate risk perception | Women possess unique knowledge related to pasture management and natural resource use, but this knowledge is rarely integrated into formal management due to gender-blind governance structures, weakening social-ecological resilience. |

| [42] | Kenya | Crisis-based food and water knowledge | Social networks among pastoral women facilitate the sharing of knowledge and resources, strengthening community resilience and supporting collective decision-making processes |

| [43] | Kenya | Watershed and adaptation training | Male-dominated learning groups limited women’s participation |

| [49] | Ethiopia | Land tenure and customary authority | Matrilineal households retained female land decision roles; formalisation displaced many women and young men. |

| [50] | Kenya | Household adaptation strategies | Social networks, including relatives, friends, and community organizations, play a crucial role in adaptation by providing strong social bonds and linkages to external resources. These networks facilitate diffusion of innovations and resource sharing. |

| [52] | India | Seed saving, soil conservation | Women manage seed and soil conservation; male knowledge prioritised in formal systems |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dormal, W.A.C. Gendered Power in Climate Adaptation: A Systematic Review of Pastoralist Systems. World 2025, 6, 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040131

Dormal WAC. Gendered Power in Climate Adaptation: A Systematic Review of Pastoralist Systems. World. 2025; 6(4):131. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040131

Chicago/Turabian StyleDormal, Waithira A. C. 2025. "Gendered Power in Climate Adaptation: A Systematic Review of Pastoralist Systems" World 6, no. 4: 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040131

APA StyleDormal, W. A. C. (2025). Gendered Power in Climate Adaptation: A Systematic Review of Pastoralist Systems. World, 6(4), 131. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6040131