1. Introduction

Talent competitiveness refers to the ability of a country or a region to cultivate, attract, and utilize talent resources for its economic and social development, as demonstrated by its talent strategy, policy, and deployment, thereby contributing to the development of the region or the country [

1]. National competitiveness is influenced by higher education and scientific research systems, both of which depend on talent competitiveness. Countries around the world have introduced several talent policies to promote national development. In 2022, the UK’s Research and Innovation Agency (RIA) formulated its Strategy 2022–2027: Changing the Future Together, focusing on building a system of excellence in research and innovation to achieve the goal of becoming a global science and technology powerhouse and an innovation-driven nation [

2]. In 2023, the U.S. Federal Government introduced its STEM education plan for the period 2023–2028, which was laid out in four areas including education, social engagement, workforce development, and research & innovation capability, as the key support for the U.S. to maintain its global leadership in science and technology [

3]. In China, another major economy in the world, the synergistic development of science, education, and talent is seen as fundamental and strategic for the comprehensive construction of a modern socialist country [

4]. In both the West and the East, talent search has been recognized as the most important task over decades [

5].

The European Institute of Business Administration (hereinafter, INSEAD), established in 1957, is headquartered in Fontainebleau, France, with additional campuses in locations including Singapore and Abu Dhabi. INSEAD’s educational mission is to develop future business leaders with a global perspective, a strong sense of responsibility, and the capacity to drive meaningful impact. The institution offers a diverse portfolio of academic programs, including the MBA program, designed to cultivate senior leadership talent; the Executive MBA (EMBA) program, targeting mid- to senior-level managers; and the PhD program, which focuses on rigorous academic research. In addition to its degree offerings, INSEAD engages in specialized research initiatives led by expert teams that integrate resources from multiple sources to conduct focused academic investigations and produce comprehensive database reports. One such initiative is the Global Talent Competitiveness Index (hereinafter, GTCI) project, which is discussed in detail in the following section.

To assess and monitor the landscape of global talent cultivation, INSEAD has taken the lead in launching the GTCI. The GTCI index focuses on the ability of countries or economies to cultivate, attract and retain talent, and has received extensive attention from academics for its comprehensiveness, international comparability, dynamic monitoring capability, and policy guidance. Seminal studies have examined the effectiveness of the GTCI. By analyzing the role of talent in the economic development of various countries and economies, researchers suggest that the GTCI could be used as a competitiveness measurement standard [

6] as it assesses a country’s talent competitiveness from a comprehensive and objective perspective [

7].

Pioneering research has used the GTCI data to conduct international comparisons. After an in-depth analysis of the G20 countries’ performance in talent competitiveness, researchers found that developed countries are particularly strong in talent competitiveness [

8]. Some scholars have also examined the migration status of 25 countries and found a positive correlation between a country’s migration status and its GTCI performance, highlighting the importance of talent competitiveness in driving a country’s development [

9]. Moreover, several studies have utilized the GTCI data for dynamic monitoring and analysis: using the European innovation scoreboard, scholars have analyzed the changes in Poland’s GTCI data between 2013 and 2018 and pointed out the challenges for talent management and innovation [

10]. These capabilities provide important research insights for policymakers, business leaders, and academic researchers worldwide.

Extending the aforementioned literature, this study takes GTCI as the key data source and selects G20 countries as the main objects of analysis. In the past, the established literature from the fields of political economy [

11], development studies [

12], and public policy [

13] has carefully sketched the issue of China’s talent competitiveness. However, few studies have compared the talent competitiveness of China with a representative coalition of countries such as the G20, resulting in a lack of international comparative perspective. At the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, Chinese scholars had already begun to pay attention to the issue of talent competitiveness and to build China’s assessment system in the foreground [

14]. However, as of 2024, there is still no substantial breakthrough drawn on such a comprehensive database as the GTCI database.

As of now, the scholarly discussions on the issue of talent competitiveness in Chinese academia focus on two aspects: (a) analyzing talent competition between regions and (b) providing vague suggestions for policy-making without detailed solutions. This is caused by China’s rapid development in the 21st century, which leaves regional competition being the focus of public policy research while talent competitiveness is an accessory. At the same time, there is a research gap between economic advancement and educational development: globalized economic development requires China to have a more developed talent competitiveness system, but the mainstream examination-based education system is not conducive to such development.

Thus, in studies focusing solely on China’s talent competitiveness, there are three research gaps that can be summarized. First, due to the lack of national-level datasets, most of the existing studies are based on individual provinces in China and are not generalizable enough. Second, current Chinese-language research in talent competitiveness mainly focuses on local policy slogans, with relatively broad arguments and a lack of empirical data support. Third, relevant studies in English language still have not proposed a set of systematic, comprehensive evaluation frameworks to measure the competitiveness of talents across the world, which hinders academics from deep diving into talent policies.

Additionally, there is an unmet need of highly skilled professionals in China, partly due to the disadvantage of its education system. China’s low attractiveness to talent has also led to a large number of Chinese overseas students being reluctant to return to China and foreign talent being reluctant to enter China [

15]. The lack of a scientific evaluation system is not conducive to the updating of talent competitiveness policies at the national level, thus leading to a vicious circle of local talent competitiveness policies.

Given this, this research proposes and adopts an original analysis matrix as a multi-dimensional and multi-indicator framework (which we name PEST-embedded SWOT matrix), for assessing talent competitiveness. By comparatively analyzing the performance of different countries in terms of talent competitiveness, this investigation aims to accurately grasp China’s position and posture in the global talent competition, thereby putting forward targeted improvement paths and policy recommendations in terms of talent cultivation, attraction, and utilization. We aimed to conduct a comprehensive literature analysis and introduce an analytical matrix to extract the indicators embedded in the GTCI data that influence China’s talent competitiveness. These indicators are compared with those of G20 countries to explore the underlying reasons for observed changes. Through this comparative analysis, we seek to identify the key factors shaping China’s talent competitiveness and examine the political, economic, social, and technological deficiencies contributing to these challenges. This research will provide valuable insights into strategies for enhancing China’s talent competitiveness. Furthermore, we will lay the groundwork for developing a national talent competitiveness assessment system tailored to China’s specific context. In subsequent research, the current absence of a standardized and unified evaluation framework is expected to become increasingly evident.

Building upon this research, we aim to develop a standardized and unified talent competitiveness assessment system for China. Ideally, this system will adopt a dual structure, comprising a nationally unified framework as the core, complemented by region-specific subsystems that reflect local cultural and contextual variations. This ambitious initiative represents the practical application of preceding theoretical research. However, achieving this objective necessitates a solid foundation of theoretical inquiry grounded in current realities, drawing upon the well-established GTCI talent competitiveness evaluation model. Accordingly, this study employs a SWOT-PEST analytical matrix (political, economic, social, and technological) to systematically examine the key factors shaping China’s present talent competitiveness landscape.

2. Materials and Methods

The utilization of data enables the provision of more objective and scientifically grounded evidence for research. This study aims to extract relevant indicators from the publicly available GTCI database to facilitate comparative analysis of talent competitiveness and to inform the development of a tailored talent competitiveness assessment system for China.

Clarifying data sources and theoretical frameworks is key to ensuring the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the study. As an authoritative assessment tool, the GTCI provides rich data support and a multi-dimensional analytical perspective for research on global talent competitiveness. Through the aggregation of the GTCI data over the past decade and the flexible application of the theoretical framework, the findings are expected to provide evidence to support strategic planning on talent competitiveness.

2.1. Data Sources

The GTCI, initiated by INSEAD, is based on the Networked Readiness Index (NRI) and the Global Innovation Index (GII). The GTCI combines the assessment of national inputs and outputs on the development of talent to build an integrated measurement model [

16]. With the deepening of globalization and the advancement of information technology, talent competition has intensified in various countries, which have coincidentally chosen to develop their talent pool and optimize relevant policies. Against such a backdrop, the GTCI has become a decision-making tool for governments, enterprises, and other stakeholders, assisting countries to better understand their talent needs and optimize their national strategies for cultivating, attracting, and retaining talent, thus enhancing their international competitiveness. The data are publicly available for free download on the INSEAD website (

https://www.insead.edu/global-talent-competitiveness-index, accessed on 20 January 2025).

In recent years, the coverage of the GTCI has been expanding, with the number of countries covered growing from 103 in 2013 to 134 in 2023. Its indicators have been enriched and improved as well, reaching a cumulative total of more than a hundred indicators over 10 years. The indicators are divided into three levels, and the overall measurement indicator is an input-output integrated model that combines the assessment of what a country does to acquire and develop talent (i.e., the inputs) with the type of skills that are the result (i.e., the outputs).

Within this input-output integrated model, there are a total of six indicators at the first level. The first indicator is ‘Enable’, which includes three secondary indicators: policy environment, market environment, business, and labor market environment. The second is ‘Attract’, which includes two secondary indicators, namely internal openness and external openness. The third is ‘Grow’, which includes three secondary indicators: formal education, lifelong learning, and development opportunities. The fourth is ‘Talent Retention Capacity’, including two secondary indicators of life maintenance and quality of life. The fifth is ‘Vocational and Technical Skills’, including the proportion of obtaining intermediate skill certificates and two secondary indicators of employability; The sixth is ‘Global Knowledge Skills’, including the proportion of obtaining high-level skill certificates and the value of creativity of talents (see

Table 1).

However, since the breakdown of indicators covered by the GTCI changes from year to year, it is difficult to harmonize the indicators extracted by researchers in their analysis, as they vary from year to year. In addition, the variability of indicator settings across years hinders the established literature from directly utilizing raw data of the GTCI for long-term period analysis. Given this, this investigation arranges and regroups the raw data based on the GTCI from 2013 to 2023. Horizontally, this investigation uses stratified purposive sampling and efficacy sampling to screen out one lower-middle-income country, eight upper-middle-income countries, and ten high-income countries from the countries covered by the GTCI data.

Longitudinally, this investigation analyzes the ten-year GTCI data for trend analysis and overall comparison over a relatively long period. Compared with the original GTCI data, the new data columns formed after processing are more complete in terms of data regularity and cross-country comparability. By comprehensively summarizing the GTCI data over the past decade from 2013 to 2023, this investigation can explore China’s position and strategies in the global talent competition, thereby providing empirical evidence to support policymaking in the fields of international talent competition. As of 30 November 2024, a total of 11 issues have been published from 2013–2024 (data for 2015 and 2016 are combined as one issue). In this investigation, a total of 10 issues from 2013–2023 are selected.

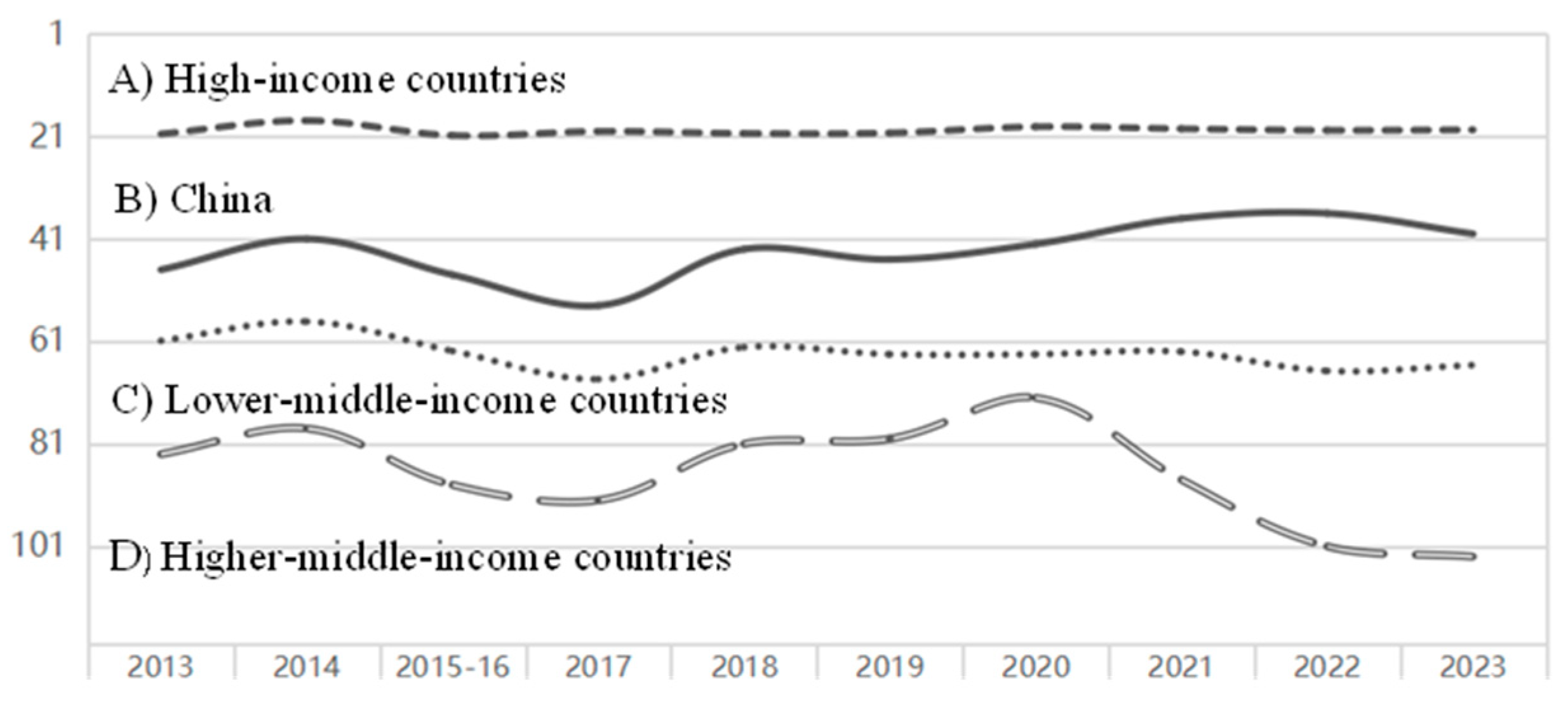

Specifically, in

Table 2 “Overall Ranking of Talent Competitiveness of Selected Representative Countries over the Decade” for example, we adopt stratified purposive and efficacy sampling. After stratifying by income level according to the GTCI classification, we select high-profile, representative local powers across every continent. In the end, one lower-middle-income country is selected, namely India. Eight upper-middle-income countries are selected, including China, Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Turkey. Ten high-income countries are selected, covering Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. Based on a similar methodology, we further rank the GTCI’s annual journal rankings for all indicators by year (

Table S2) and rank China’s yearly performance over the decade for all indicators (

Table S3). By aggregating and analyzing the GTCI data in detail for the decade from 2013 to 2023, this investigation can delve deeper into China’s position and strategies in the global talent competition, thereby providing empirical evidence to support policymaking in the area of international talent competition.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

To analyze the contributing factors to China’s talent competitiveness, this investigation combines the PEST (Political, Economic, Social, and Technological) model and SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis to construct the PEST-SWOT model matrix (see

Table 3). Among them, the PEST analysis model is a model for industry or enterprise macro-environmental analysis, which includes political, economic, social, and technological factors. The multidimensional analysis of the external environment in the PEST analysis model can constitute the OT (opportunities and threats) part of the external factors in the SWOT analysis model.

The SWOT analysis method is a tool commonly used in corporate strategic planning by considering four aspects, namely strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats [

17], of which strengths and weaknesses belong to the enterprise’s internal factors while the opportunities and threats refer to the impacts of the external environment on the enterprise [

18]. The two matrix components, PEST and SWOT, interact dynamically, with the four macro-assessment dimensions of PEST—politics, economy, society, and technology—remaining fluid. These dimensions vary across different countries and historical periods, reflecting the broader global context of each era. Such changes shape a unique form of the PEST system within the SWOT framework, ultimately generating a PEST-SWOT analysis matrix tailored to a country’s current historical stage. This matrix can be seamlessly integrated with various sectors of the country.

By revisiting the definition of talent competitiveness introduced earlier in the article, it becomes evident that this concept is closely linked to PEST-related factors, particularly politics and economy, within a given time frame. Talent competitiveness exhibits a dynamic and evolving nature, aligning well with the fluidity and macro-level characteristics of the PEST-SWOT matrix. Therefore, the PEST-SWOT matrix serves as a foundational component in the evaluation of talent competitiveness.

Within the SWOT structure, SW (Strengths and Weaknesses) and OT (Opportunity and Threat) represent two analytical perspectives, each encompassing two distinct dimensions. The SW (strengths and weaknesses) analysis in this study centers on the strengths and weaknesses that affect China’s global talent competitiveness ranking and combines with the PEST analysis to focus on the point of the SW analysis. The OT (Opportunity and Threat) analysis in this study mainly analyzes the outstanding indicators of G20 countries in global talent competitiveness, searches for China’s talent policies and strategic plans, and analyzes the opportunities and challenges that a country may face in the development of talent competitiveness in the future. Building on this foundation, we integrate two perspectives with four dimensions to create the SO-PEST, WO-PEST, ST-PEST, and WT-PEST cross-analysis system. This system aligns with the evolving nature of PEST and the dynamic flow of talent competitiveness, offering a more detailed framework for analysis. The following section will further emphasize this cross-analysis approach.

Developing SWOT analysis from the four types of the PEST macro-factors can be called the PEST-embedded SWOT model [

19], or the PEST superimposed SWOT analysis framework. Based on the PEST-embedded SWOT model, such an analysis model of talent competitiveness is constructed to combine the internal strengths and weaknesses of improving China’s talent competitiveness with the analysis of the external macro-environments. By analyzing both internal and external aspects, it can put forward feasible strategies for China’s talent competitiveness.

2.3. Data Export and Data Analysis Methods

The GTCI Journal is an open-source resource available for download as a PDF. Its overarching structure consists of three main sections: a background introduction, an explanation of the ranking methodology for talent competitiveness, and the ranking of countries. The number of participating countries and the indicators used to measure talent competitiveness may vary over time.

Our analysis focuses on the overall talent competitiveness rankings of G20 countries, as well as their rankings across specific measures outlined by the GTCI. To facilitate this, we extract the data into a Word document on a country-by-country basis and use its editing functions to isolate the rankings and metrics, presenting them in an editable text format.

Next, we compile the overall rankings of G20 countries for each year from 2013 to 2023 (see

Table S1). We then list the rankings of G20 countries for each indicator across these years (see

Table S2).

Finally, to provide a more detailed view of China’s performance and to track changes in the number and naming of indicators, we present China’s rankings for each indicator by year, highlighting newly introduced or renamed indicators. This process results in a comprehensive summary of 106 indicators for China over a ten-year period (see

Table S3).

Due to the large number of years involved and the large number of indicators, each table has more content than can be well presented in the main text. We have therefore included them as

Supplementary Materials, the details of which can be found in the

Supplementary Materials.

4. Results

In this investigation, we further analyze the strengths and weaknesses of China’s talent competitiveness in the political, economic, social, and technological domains through the PEST-SWOT matrix. After analyzing key indicators, it can be seen that China’s talent competitiveness has shown an overall upward trend from 2013 to 2023. Meanwhile, we can observe the penetration rate of secondary and higher education enrollments, the improvement in poor education hardware, the support of the business and policy environment, and the start and construction of lifelong learning. There are also improvements in social tolerance, external openness, vocational skills education system, and vocational certificate system (see

Table S2).

At the same time, however, due to multiple factors such as being a latecomer, having uneven distribution of resources, and lacking resources, China differs from Europe and the United States in many aspects. Particularly, we must note the imbalance in China’s development, where development centers are excessively distributed in eastern China, resulting in a large amount of wasted talent resources in the east. The inability to demonstrate talent competitiveness will further result in wasted time and resource costs, making it impossible for China to achieve sustainable development.

4.1. Positive Influences on China’s Talent Competitiveness

Strengths in governance lie in the optimization of policies and the enhancement of social protection. Over the past decade, China’s GTCI ranking in government effectiveness has increased significantly, from the 61th to the 36th. Now, GTCI ranks China as the top non-high-income countries in the G20 countries, with a strong government ability to implement policies, provide public services, and meet the increasing needs of its citizens. At the same time, the rule of law environment has gradually improved in China, particularly in terms of the efficiency of contract fulfillment, the clear definition and protection of property rights, the defense of citizens’ rights, and the quality of services provided by the police and the judiciary. In the composition of pensions from 2005 to 2015, the ratio of the workforce contributing to the pension system increased from 34% to 69.80% in GTCI data. China’s pension coverage is now among the highest in upper-middle-income countries. In addition, corruption perceptions have improved year on year, with the GTCI ranking progressing from the 76th to the 53rd, reflecting the effectiveness of the government’s fight against corruption (See

Table S2 for

Section 4’s data; the same below).

China’s strengths in the area of economic development lie in the improvement of its human and market management systems as well as the revitalization of its market dynamics. China’s extent of market dominance is ranked in the top 10 globally by GTCI, much higher than that of many high-income countries. In terms of market competition intensity, China’s ranking has been risen from the 38th to the 4th place gradually. In terms of China’s business environment, domestic credit to the private sector ranks 5th in the world by GTCI, second only to the U.S. and Japan among the G20 countries. With the business environment has been continuously optimized in China, the ease of doing business has risen from the 68th to the 29th in GTCI ranking. Meanwhile, China’s level of labor-management cooperation has risen in the GTCI ranking, and the index of specialized management has risen to the top 20 as well. Moreover, China’s performance in the relevance of education system to the economy has risen from the 50th to the top 10 as measured by GTCI, and its highly educated unemployment rate is 1.84%, ranking the 7th in the world by GTCI. The ease of finding skilled employees in China has also risen to the 4th place, being the highest among the G20 countries in GTCI ranking.

China’s strengths in the area of social development include an emphasis on talent acquisition and training as well as the establishment of education and social security systems. The social mobility of Chinese society as a whole is on an upward trend, rising from a low rank of the 67th to the 33rd according to the GTCI global ranking. China’s rank has been second only to Indonesia among the G20 middle- and high-income countries in 2023, and is higher than those of high-income countries such as France, Italy, and the Republic of Korea. China’s tertiary education enrollment rate has risen from the 73rd to the 49th in the GTCI ranking as well and has been ranked 1st several times in the world in reading, math, and science in the PISA test. China is also ranked 3rd in the world in terms of the number of universities listed in the world’s top 100 universities in the QS rankings. In the GTCI ranking, China’s performance of brain gain has risen to the 7th by 2023, and the prevalence of in-house training is ranked 1st in the world with a share of 79.20% by 2022. China’s performance in employee development has also risen from a low rank of the 47th to the 14th by 2022. In addition, the level of financial assistance to people who are unemployed or disabled has increased in China, while the relationship between pay to productivity has risen from the 13th to the 3rd in the GTCI ranking.

The strength of China’s higher education and research systems lies in the advancement of research in both universities and enterprises as well as the development of daily technologies. The percentage of China’s national R&D expenditure in overall GDP has risen from 1.70% in 2010 to 2.41% in 2021, placing it at the top of the G20’s middle and high-income countries. China’s innovation output has been ranked as high as the 5th globally in the GTCI ranking. Its ICT infrastructure investment data is ranked first in the world in 2022, and the cloud computing market size has ranked top among the G20’s middle- and high-income countries. The use of virtual social networks in China is popular, with the penetration rate reaching 72% in 2022. China’s cluster development situation has also ranked second in the world as of 2022, second only to the United States. New product entrepreneurial activities, measuring the new services or innovative products provided by start-ups to customers, reached a peak average of 76.91% in 2016—This performance is ranked third worldwide and first among G20 countries.

4.2. Negative Influences on China’s Talent Competitiveness

China’s disadvantage in the area of government governance lies in the lack of policy and regulatory effectiveness. GTCI’s data on Active Labor Market Policies (ALMPs) from 2016 to 2018 indicate that policy effectiveness is on a downward trend in China. In addition, the incentive effect of the tax system has weakened, and incentives for work or investments have trended downward from 2012 to 2015. The performance of China on GTCI’s regulatory quality (RQ) indicator has fluctuated over an extended period, ranking 88th globally in 2023, which is at the tail end of the G20 countries. Although the Chinese government has adopted active labor market policies to promote retraining and employment of the unemployed people, such policies have not been as effective as expected. The declining incentives of the tax system discourage firms from investing in talent development and innovation, negatively affecting individuals’ motivation to work and their willingness to start businesses in China. Inadequate capacity to regulate quality affects the fairness of the market environments and the development of the private sector, and hence is not conducive to the attracting and development of talent.

Disadvantages in the area of economic development include issues within forms of employment and foreign economic cooperation. China’s foreign investment restrictions are characterized by a low prevalence of foreign ownership and strict regulatory restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI). In recent years, China’s financial globalization has been ranked outside the 110th in the GTCI ranking and is at the bottom of the G20’s high-income countries. There is also a lack of efforts to match educational training and career skills. Between 2013 and 2020, while China’s secondary education is relatively well matched with an average ranking of the 24th globally, tertiary education is poorly matched with only an average ranking of the 45th in GTCI data. Meanwhile, China’s labor productivity per employee is low, with an average ranking of the 74th: Their performance is at the bottom of the G20 countries and there is a large gap between China and high-income countries. Foreign investment and internationalization restrictions affect the international flow of capital, technology, and talent. The mismatch between the education system and market demand in China results in a waste of talent resources. In addition, the low labor productivity reflects the shortcomings of enterprises in improving efficiency and innovation, which is not conducive to attracting and retaining talent.

Disadvantage in the area of social development includes the poor social security system. China has a low level of social inclusion and diversity, with an average GTCI ranking of the 85th in terms of tolerance of immigrants. It is coupled with a declining performance of China on migrant stock, with its GTCI ranking dropping from the 109th to the 134th. Meanwhile, the inflow of international students to China has decreased significantly, with the percentage of newly enrolled international students in all newly enrolled university students dropping from the 72nd to the 103rd globally. Moreover, China’s GTCI rankings in indicators about talent retention are all outside the 30th percentile globally. For vocational education, the enrollment rates in vocational colleges in China have dropped from 20.83% (ranked 30th globally) to 18.30% (ranked 45th). Concerning basic social security, China’s GTCI ranking in environmental protection has dropped to the 120th. The number of doctor degree holders per capita in China, despite growing from 1.42 per 1000 in 2013 to 2.39 per 1000 in 2023, ranks only 66th globally according to GTCI data. The lack of social inclusion in China affects the integration of expatriate talent while declining international student inflows and poor talent retention reflect China’s lack of attraction to international talent in higher education. The declining enrollment in vocational education also underscores the lack of investments in the vocational education and training sector. The low rankings for environmental protection and the density of doctor degree holders suggest that basic social rights and health protection should be further improved in China.

Disadvantages in higher education and scientific research include insufficient innovation dynamism and foreign cooperation. China’s international competitiveness and foreign technological cooperation are limited, with the share of high-tech exports falling from 32.83% in 2013 to 29.96% in 2023 as recorded. The developments of digitalization and informatization are insufficient in China: the share of output value created by enterprises with official websites in 2021 is only around 66.20%, ranking 42nd in the world according to GTCI data. Meanwhile, the share of technical professionals and auxiliary staff is low, with figures of only 3.35% and 7.30% in 2022, ranking the lowest among the G20 countries. China is also weak in technological innovation and R&D, with an average ranking of the 56th in the rate of technology adoption at the enterprise level. The ratio of R&D experts in China has also declined from 2384.95 per million people in 2009 to 1584.87 per million people in 2021. The decline in high-tech exports limits the technological upgrading and international competitiveness of Chinese enterprises, and the low penetration rate of enterprise-owned websites affects the development potential of the digital economy. The insufficient proportion of professionals affects China’s talent support and strategic planning capacity in key areas, and the lagging technological application with insufficient R&D professionals weakens China’s technological innovation and R&D capacity [

41].

6. Conclusions

As highlighted by the Chinese government, the implementation of its national strategy, alongside the acceleration of building a global talent hub and an innovation highland, requires continuous enhancement of talent competitiveness. This includes deepening the triple-helix of science, education, and talent, which serves as the cornerstone for constructing Chinese-style modernization [

53]. Based on data from the Global Talent Competitiveness Index (GTCI) and utilizing the PEST-SWOT analysis model, this study provides an exploration of China’s talent competitiveness, examining both its strengths and weaknesses. Analysis results offer practical recommendations for improving talent competitiveness.

This research also aims to offer insights for decision-making regarding talent education and development from an international comparative perspective. While a growing body of academic literature has well examined China’s talent competitiveness over the past few decades, much of the existing research is focused on specific provinces in China and lacks nationwide data, let alone a cross-country comparative study. In contrast, this research leverages large-scale data to present a macro-level overview of China’s talent competitiveness and then compares it with the general situation in G20 countries. The findings are expected to contribute to and extend existing literature in public policy, development studies, and political economy.

Specifically, China should strengthen its appeal to foreign talent in the dimension of talent attraction and retention. While the number of foreign students and long-term residents in China remains relatively low, the Chinese government has implemented policies such as upgrading the visa system and enhancing its livelihood security. These policies have facilitated the work and life of foreign talent in China. However, compared to European and American countries such as the UK and the U.S., China still faces challenges in terms of anti-discrimination and living environment protection. A sense of alienation persists and, in some cases, there is discrimination against foreigners. Additionally, the Chinese government has not effectively implemented measures that support foreign residents in integrating into the Chinese culture. These have made it less likely for foreign talents in China to develop a sense of belonging, which in turn diminishes their happiness and enthusiasm for living in China in the long term.

Concerning talent training capacity, China should strengthen its knowledge foundation and improve its educational system. In recent years, China has made multiple investments in the development of education in rural areas, particularly through aid to impoverished villages. Substantial funding has contributed to tangible progress in the physical infrastructure of these villages. However, there remain significant gaps in policy execution. For instance, the rural teachers’ salary and title appraisal systems have not been fully implemented, and there is a lack of a coherent teacher management system. As a result, many teachers in China are not receiving adequate compensation, which undermines their motivations to work in rural areas. The lack of financial incentives and the insufficient management system continue to impede the resolution of rural education challenges in China. Additionally, China’s education system is largely focused on examination-based, which can be overly utilitarian. The emphasis on exams rather than fostering a culture of lifelong learning has led to a lack of enthusiasm for self-exploration and personal development among people.

In the area of vocational education and industry-academia cooperation, China should place greater emphasis on practical-oriented education. While significant progress has been made in vocational education over the past decades, with increased government attention and substantial advancements in both institutional and material infrastructure, challenges remain. One key challenge is the gap between vocational education and academic research. This gap creates barriers that limit the talent development and prevent the mutual exchanges between vocational and academic education. However, the importance of vocational education is receiving increasing attention from the Chinese government. Reforms in vocational education have already begun pilot trials in major cities such as Beijing, and we believe that the integration between higher education and vocational education will gradually be strengthened. In contrast, countries such as the U.S. (through community colleges) and Germany (through its “dual education system”), have established systems that facilitate the exchange and integration of vocational and academic education, respecting the interests of students and fostering their growth.

In the dimension of science, research and innovation, China should further promote international cooperation. Over the past two decades, China has made large investments in expanding its university enrollment system, for increasing the number of university students. The implementation of well-structured university training programs has also focused on developing students’ capabilities of research and innovation. Concurrently, the college entrance examination system has reinforced the authority of knowledge. These efforts have led to the cultivation of a substantial number of research talents, with scientific achievements being globally recognized. Chinese international students are spread across the world in large numbers, serving as a valuable channel for global exchange. However, as discussed in

Section 3, China’s higher academic institutions engage in less international collaboration compared to other countries. China should actively participate in global academic exchange platforms and strengthen cooperation with the countries where its students study, fostering more interaction. This will help enhance the integration of Chinese international students with local academic and cultural environments.

From a macro perspective, we have summarized several key challenges that impact China’s ability to develop its own talent competitiveness:

- A:

The mismatch between material infrastructure and management systems;

- B:

The discrepancy between system development and policy implementation;

- C:

The insufficient international cooperation in innovation, research, and education.

Together, these four issues result in limitations on China’s talent development, preventing the full realization of talent’s potential.

Correspondingly, by adopting a PEST-SWOT matrix, our analysis suggests that China should focus on improving the following areas:

The most fundamental challenge in rural education reform is the migration of a large number of rural residents to urban areas, which has weakened the cohesion of rural communities. This migration has also led to a shortage of resources and an underdeveloped education system.

We believe that the traditionally strong culture of self-reliance in rural China, rooted in the ancient notion of clans, has contributed to a decline in cooperative efforts among rural communities, especially following the loss of young laborers. However, fostering cooperation through the establishment of agricultural cooperatives could be a viable solution. By forming rural cooperatives, children at the school-age level can be grouped, creating a student population and an educational demand comparable to that of an urban elementary school. This increased demand for education can attract greater government investment in rural areas. Additionally, a concentrated student base makes it easier for the government to implement standardized educational policies and allocate resources efficiently, ultimately optimizing the rural education system.

To achieve this goal, we propose the following recommendations:

- A:

The first step is to coordinate inter-village cooperation. The Chinese government, at all levels, should strengthen the legal framework for rural education, implement policies to support rural education at a macro level, and enforce laws as necessary to ensure compliance and consistency.

- B:

Municipal and county governments should deploy civil servants with expertise in education and coordination to rural areas. These officials should work with local village councils to facilitate inter-village cooperation, ensuring that children receive concentrated educational resources.

- C:

Cultural promotion should be enhanced to encourage interaction among villagers. Local governments should organize community gatherings and, based on geographical conditions, consider appropriate population relocation or infrastructure development. Establishing better facilities will enable the creation of centralized schools that serve multiple villages.

To attract foreign talent effectively, changes should be implemented at a more humanistic and localized level. While China has established policies that support the life and work of foreign professionals, challenges remain in execution and social integration.

- A:

Each city should establish cultural hubs that reflect international influences, providing foreign professionals with spaces for socialization and networking. Additionally, local governments should organize cultural exchange trips, allowing foreign talents to engage with local communities, experience Chinese culture, and enjoy regional cuisine. This initiative will help bridge the gap between foreign professionals and local residents, fostering deeper social integration.

- B:

Many English-speaking professionals remain underutilized. The government should create grassroots positions dedicated to supporting foreign talents, offering them direct communication channels to address challenges they may face. This initiative would not only alleviate employment pressures but also strengthen foreign professionals’ sense of belonging in China.

- C:

Efforts should be made to break stereotypes and recognize the value of foreign professionals. Local governments should provide foreign talents with opportunities beyond their primary jobs, allowing them to engage with the community in meaningful ways. For example, inviting foreign professionals to participate in school exchanges and guest lectures can enhance their sense of contribution and belonging.

One of the most pressing issues in these areas is China’s lack of a unified and scientific talent evaluation system. As mentioned earlier, many developed countries have established their talent assessment frameworks, with some even implementing international evaluation systems such as the Global Talent Competitiveness Index (GTCI). However, China has yet to develop a comparable system and remains at an early stage, where provinces and cities still treat talent as a bargaining chip in regional competition.

To address this issue, we propose the following recommendations:

- A:

Establish a unified, scientific talent evaluation system at the national level to ensure systematic recognition of talent contributions. The government should take the lead by leveraging macro-level policies to guide the academic community in shifting its research priorities. This shift should move away from localized competition toward the creation of a national talent evaluation framework that supports scientific research and vocational education. The system should be designed to inform improvements in both vocational training and broader educational fields.

- B:

Strengthen international educational exchanges and collaborations to bridge the gap between China and the global academic community. This includes expanding opportunities for scholarly visits, providing scholarships for international studies, and encouraging universities to establish research partnerships with institutions abroad.

- C:

Capitalize on the growing interest in vocational education by developing a communication and transfer system that integrates vocational and academic education. This would expand career development pathways and create a more flexible education model. In alignment with the establishment of a talent evaluation system, China should take inspiration from European countries, the U.S., and Singapore in building a lifelong learning system tailored to its own needs, integrating it with the national talent assessment framework.

In addition, we also recommend to improve policy formulation and implementation by ensuring alignment with material construction and management systems. Specifically, China should strengthen its mechanisms to ensure the effective execution of policies and create a balanced pace between material infrastructure and system management.

We conclude that China should implement a talent competitiveness enhancement program to break the fragmented and formalized status quo of talent cultivation. China may also consider providing an authoritative framework for talent development and value recognition, to ensure more effective and efficient talent cultivation.

This investigation also emphasizes methodological innovation. Previous research on China’s talent competitiveness relied on either qualitative analysis or a single-dimensional data analysis. There is a lack of academic work that uses multiple evaluation dimensions to assess talent competitiveness systematically. To address this gap, the study proposes and utilizes a PEST-embedded SWOT model, offering a quantitative comparison of China’s talent competitiveness with those of G20 countries. However, this research should stress the need to overcome the over-reliance on an individual data source, such as the GTCI ranking, by incorporating more diversified data and statistical methods. Additionally, future research should aim to conduct in-depth multi-case studies for a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities involved.

The GTCI report is generally highly credible, with clear and well-structured indicators and data classification, ensuring scientific rigor and reliability. Most of its rankings are consistent with conclusions drawn from other academic research and datasets.

However, while the GTCI report is updated annually, it may not fully capture the evolving complexity of political, economic, and technological landscapes, as highlighted in this study’s PEST-SWOT matrix framework. Many major economies have intricate hierarchical systems, and significant policy or structural changes occur frequently. Given these dynamics, a one-year evaluation cycle may be too short to fully reflect such developments, potentially leading to incomplete or less precise indicator rankings.

Additionally, while utilizing the GTCI report, we have identified certain limitations that may slightly impact analysis outcomes or interpretations. First, the indicators in the GTCI report frequently change. To address this, we have systematically compiled and categorized all modifications to maintain accurate classification (see

Table S3). Nevertheless, for researchers conducting large-scale analyses, adapting to these shifting indicators and naming conventions may require additional time.

In summary, the academic community still lacks a comprehensive talent value evaluation system that is effective across national contexts and can provide a common understanding of talent value. Furthermore, there have been limited explorations of cross-country comparisons of talent development and talent competitiveness. This research gap has resulted in existing academic discussions being confined to small-scope case studies based on individual countries. To address this gap, our investigation uses the Global Talent Competitiveness Index to assess China’s talent competitiveness from an international comparative perspective. The research findings can offer valuable insights decision-making in public administration, higher education, and also the private sector.