Government Revenue Structure and Fiscal Performance in the G7: Evidence from a Panel Data Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Contemporary Fundamentals of Fiscal Policy in Developed Economies

2.2. Tax Structure: Direct Taxes, Indirect Taxes and Social Contributions

2.3. Tax Innovations and Emerging Sources of Revenue in G7 Economies

2.4. Comparative Empirical Models and the G7-OECD-BRICS Perspective

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussions

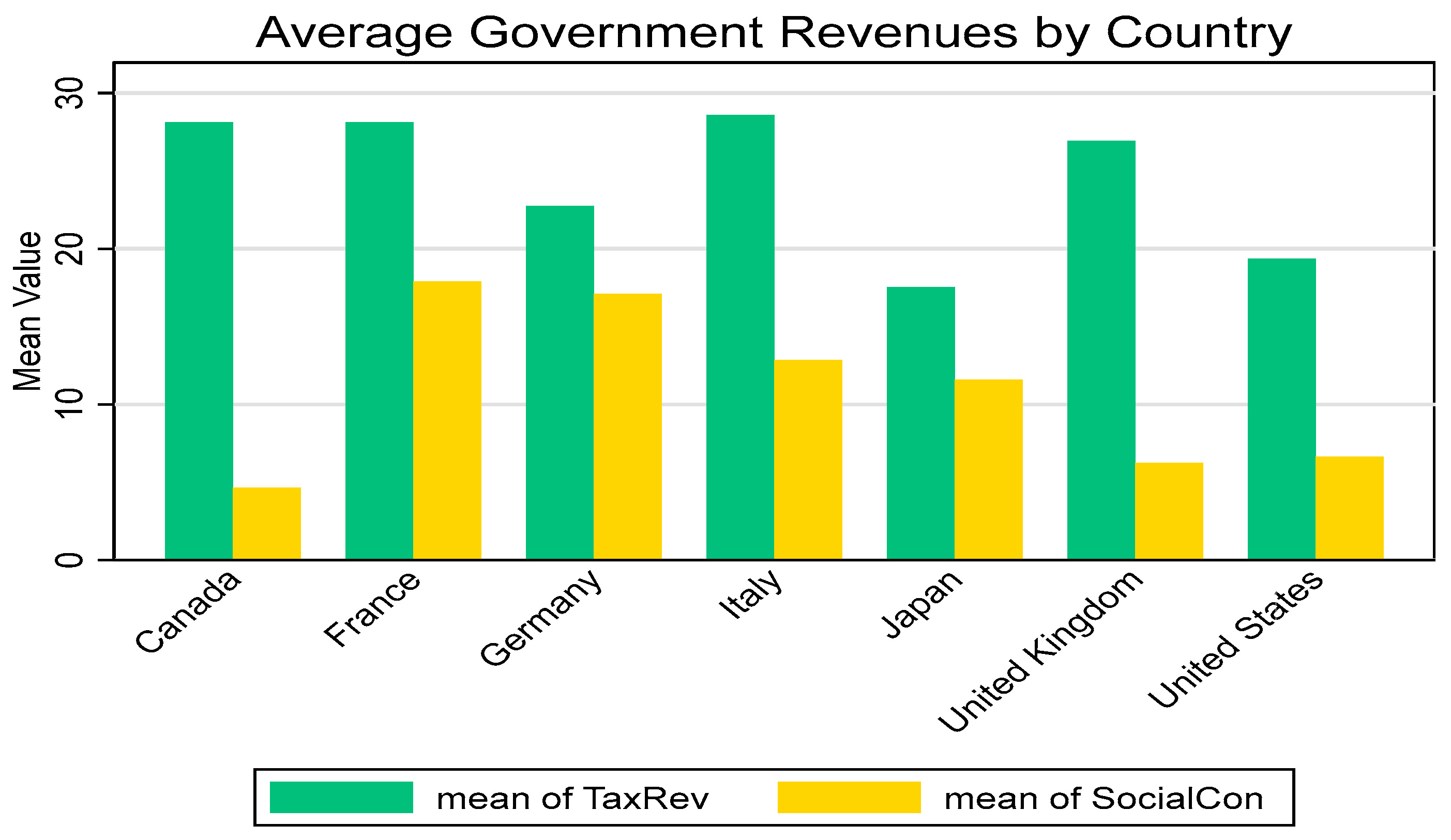

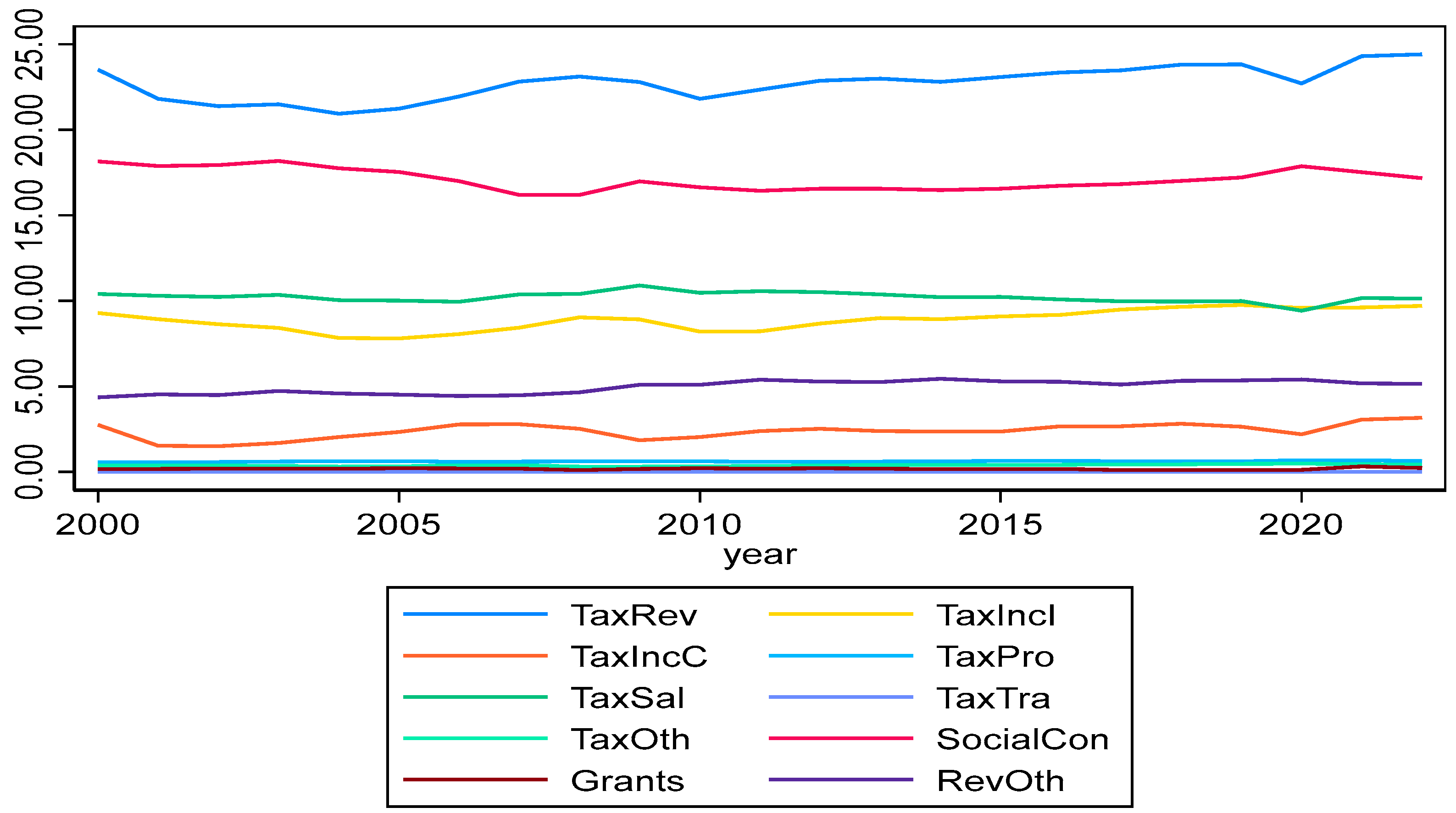

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Matrix of Correlations and Variance Inflation Factor

4.3. Analysis Linear Regression

4.4. Dynamic Model Results

5. Conclusions and Implications for Fiscal Policies in the G7

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Monetary Fund IMF Capacity Development Strategy and Policies. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Capacity-Development/strategy-policies (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Saqib, N.; Usman, M.; Radulescu, M.; Șerbu, R.S.; Kamal, M.; Belascu, L.A. Synergizing Green Energy, Natural Resources, Global Integration, and Environmental Taxation: Pioneering a Sustainable Development Goal Framework for Carbon Neutrality Targets. Energy Environ. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmani, M. Environmental Quality and Sustainability: Exploring the Role of Environmental Taxes, Environment-Related Technologies, and R&D Expenditure. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2024, 26, 449–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiri, A.; Gündüz, V.; Adebayo, T.S. The Role of Financial and Trade Globalization in Enhancing Environmental Sustainability: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Carbon Taxation and Renewable Energy in EU Member Countries. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, S.; Tang, P.; Hu, Y.; Liu, M.; Qiu, S.; Iqbal, M. Role of Natural Resources, Renewable Energy Sources, Eco-Innovation and Carbon Taxes in Carbon Neutrality: Evidence from G7 Economies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Tax Policy Reforms 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/tax-policy-reforms-2023_d8bc45d9-en.html (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- European Commission. Annual Report on Taxation 2024 Review of Taxation Policies in EU Member States. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/docs_autres_institutions/commission_europeenne/swd/2024/0172/COM_SWD(2024)0172_EN.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwj61oznoK-OAxWbklYBHZ8lBDkQFnoECBcQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0s8lpcXhSVZmucAFZZj6dV (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Verdier, G.; Rayner, B.; Muthoora, P.S.; Vellutini, C.; Zhu, L.; Koukpaizan, V.d.P.; Marahel, A.; Harb, M.; Benmohamed, I.; Hebous, S.; et al. Revenue Mobilization for a Resilient and Inclusive Recovery in the Middle East and Central Asia. Dep. Pap. 2022, 2022, A001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.C.; Mansour, M.; Pecho, M.; Vellutini, C. Building Tax Capacity in Developing Countries. Staff Discuss. Notes 2023, 2023, A001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Warsame, H.; Khan, S. Tax Collections and Democracy in Developing and Developed Countries. In Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Farazmand, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 12593–12597. ISBN 978-3-030-66252-3. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton, R.E.; Fargher, L.F.; Feinman, G.M.; Kowalewski, S.A. The Fiscal Economy of Good Government: Past and Present. Curr. Anthropol. 2021, 62, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krampe, F.; Hegazi, F.; VanDeveer, S.D. Sustaining Peace through Better Resource Governance: Three Potential Mechanisms for Environmental Peacebuilding. World Dev. 2021, 144, 105508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svetlozarova Nikolova, B. Strengthening the Integrity of the Tax Administration and Increasing Tax Morale. In Tax Audit and Taxation in the Paradigm of Sustainable Development: The Impact on Economic, Social and Environmental Development; Svetlozarova Nikolova, B., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 157–180. ISBN 978-3-031-32126-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wirba, A.V. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): The Role of Government in Promoting CSR. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 7428–7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.; Murphy, R.H. An Index Measuring State Capacity, 1789–2018. Economica 2022, 89, 713–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, R.A. Theories of Fiscal Federalism. Public Financ. 1969, 24, 521–536. [Google Scholar]

- Savoia, A.; Sen, K. The Origins of Fiscal States in Developing Economies: History, Politics and Institutions. J. Institutional Econ. 2023, 19, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradlow, B.H. Urban Social Movements and Local State Capacity. World Dev. 2024, 173, 106415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K. What Is State Capacity and How Does It Matter for Energy Transition? Energy Policy 2023, 183, 113799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe, O.; Santoro, F. The Promise and Limitations of Information Technology for Tax Mobilization. World Bank Res. Obs. 2023, 38, 295–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearson, M.; Rasmus Corlin, C.; Randriamanalina, T. Developing Influence: The Power of ‘the Rest’ in Global Tax Governance. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2023, 30, 841–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root, H.L. The Religious Origins of State Capacity in Europe and China. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2024, 218, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianov, S.; Koroleva, L.; Pokrovskaia, N.; Victorova, N.; Zaytsev, A. The Influence of Taxation on Income Inequality: Analysis of the Practice in the EU Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Bernabéu, B.; and Del-Valle-Calzada, E. Tax Policies with a Human Rights Perspective: Towards Greater Tax Justice. S. Afr. J. Account. Res. 2024, 38, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roland, A.; Römgens, I. Policy Change in Times of Politicization: The Case of Corporate Taxation in the European Union. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2022, 60, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cima, E.; Esty, D.C. Making International Trade Work for Sustainable Development: Toward a New WTO Framework for Subsidies. J. Int. Econ. Law 2024, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.S.; Amin, N.; Shabbir, M.S.; Song, H. Going Green in ASEAN: Assessing the Role of Eco-Innovation, Green Energy, Industrialization, and Environmental Taxes in Achieving Carbon Neutrality. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 33, 3596–3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Rahman, M.M.; Xinyan, X.; Siddik, A.B.; Islam, M.E. Unlocking Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance through Energy Efficiency and Green Tax: SEM-ANN Approach. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajeigbe, K.B.; Ganda, F.; Enowkenwa, R.O. Impact of Sustainable Tax Revenue and Expenditure on the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goals in Some Selected African Countries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 26287–26311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy—Subject to Tax Rule (Pillar Two): Inclusive Framework on BEPS. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-subject-to-tax-rule-pillar-two_9afd6856-en.html (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Tax Foundation Europe. Digital Taxation Around the World. Available online: https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/global/digital-taxation/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- OECD. Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/base-erosion-and-profit-shifting-beps.html (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Alstadsæter, A.; Johannesen, N.; Le Guern Herry, S.; Zucman, G. Tax Evasion and Tax Avoidance. J. Public Econ. 2022, 206, 104587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptono, P.B.; Mahmud, G.; Salleh, F.; Pratiwi, I.; Purwanto, D.; Khozen, I. Tax Complexity and Firm Tax Evasion: A Cross-Country Investigation. Economies 2024, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Lobo, G.J.; Mitra, S. Firm-Level Political Risk and Corporate Tax Avoidance. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2023, 60, 295–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, M.P. International Tax Competition and Coordination with A Global Minimum Tax. Natl. Tax J. 2023, 76, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Baskaran, A. Regional Economic Growth, Digital Economy and Tax Competition in China: Mechanism and Spatial Assessment. J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2024, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, V.J. Pillar 2: Tax Competition in Low-Income Countries and Substance-Based Income Exclusion. Fisc. Stud. 2023, 44, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, V. The Impact of Macroeconomic Policies on the Level of Taxation and the Fiscal Balance in Developing Countries. IMF Staff Pap. 1989, 1989, A005. [Google Scholar]

- Almarri, A.S. How the Law Can Ensure the Success of Value-Added Tax. Int. J. Law Manag. 2024, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cuesta, B.; Martin, L.; Milner, H.V.; Nielson, D.L. Do Indirect Taxes Bite? How Hiding Taxes Erases Accountability Demands from Citizens. J. Polit. 2023, 85, 1305–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiu (Cazacu), C.E.; Bărbuță-Mișu, N.; Chirita, M.; Soare, I.; Zlati, M.L.; Fortea, C.; Antohi, V.M. Modelling the Impact of VAT Fiscality on Branch-Level Performance in the Construction Industry-Evidence from Romania. Economies 2024, 12, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Bachas, P.; Jensen, A.; Gadenne, L. Tax Equity in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Econ. Perspect. 2024, 38, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgammal, M.H.; Al-Matari, E.M.; Alruwaili, T.F. Value-Added-Tax Rate Increases: A Comparative Study Using Difference-in-Difference with an ARIMA Modeling Approach. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valodia, I.; Francis, D. Ethics, Politics, Inequality. In New Directions; Bohler-Muller, N., Soudien, C., Reddy, V., Eds.; Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2022; pp. 173–192. ISBN 9780796926142. [Google Scholar]

- Schechtl, M. Taking from the Disadvantaged? Consumption Tax Induced Poverty across Household Types in Eleven OECD Countries. Soc. Policy Soc. 2024, 23, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Davis, A.; Klemm, A.; Osorio-Buitron, C. Gendered Taxes: The Interaction of Tax Policy with Gender Equality. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2024, 31, 1413–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALshubiri, F. Do Foreign Direct Investment Inflows Affect Tax Revenue in Developed and Developing Countries? Asian Rev. Account. 2024, 32, 781–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Hakim, T.; Karia, A.A.; David, J.; Ginsad, R.; Lokman, N.; Zolkafli, S. Impact of Direct and Indirect Taxes on Economic Development: A Comparison between Developed and Developing Countries. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2141423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, A. Direct Versus Indirect Taxes: Impact on Economic Growth and Total Tax Revenue. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2020, 11, 16112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Hicks, J.; Norton, M. How Well-Targeted Are Payroll Tax Cuts as a Response to COVID-19? Evidence from China. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2022, 29, 1321–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giupponi, G.; Landais, C. Subsidizing Labour Hoarding in Recessions: The Employment and Welfare Effects of Short-Time Work. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2023, 90, 1963–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, A.; Labidi, M.A.; Saidi, Y. The Nexus Between Pro-Poor Growth, Inequality, Institutions and Poverty: Evidence from Low and Middle Income Developing Countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 172, 703–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. The Contribution of the Social and Solidarity Economy and Social Finance to the Future of Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_739377.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Fritz, B.; de Paula, L.F.; Prates, D.M. Developmentalism at the Periphery: Addressing Global Financial Asymmetries. Third World Q. 2022, 43, 721–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, J.; Kyriazi, A.; Natili, M.; Ronchi, S. Buffering National Welfare States in Hard Times: The Politics of EU Capacity-Building in the Social Policy Domain. Soc. Policy Adm. 2024, 58, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.; Jukka, P.; Schimanski, C. The Tax Elasticity of Formal Work in Sub-Saharan African Countries. J. Dev. Stud. 2024, 60, 217–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torm, N.; Oehme, M. Social Protection and Formalization in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review of the Literature. World Dev. 2024, 181, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Hanna, R.; Olken, B.A.; Sverdlin Lisker, D. Social Protection in the Developing World. J. Econ. Lit. 2024, 62, 1349–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, M.; Huang, W. Can the Digital Economy Development Limit the Size of the Informal Economy? A Nonlinear Analysis Based on China’s Provincial Panel Data. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 83, 896–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjarwi, A.W. Tax Burden and Poverty in Lower-Middle-Income Countries: The Moderating Role of Fiscal Freedom. Dev. Stud. Res. 2025, 12, 2466511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, E.; Hill, S.; Jaber, M.H.; Jinjarak, Y.; Park, D.; Ragos, A. Developing Asia’s Fiscal Landscape and Challenges. Asia Pac. Econ. Lit. 2024, 38, 225–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, F.M.S. Social Justice and Economic Policy: Analyzing the Interplay Between Welfare and Market Forces. Open Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2025, 1, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Rashid, S.F.; Sanusi, S.; Abu Hassan, N.S. Digital Transformation: Confronting Governance, Sustainability, and Taxation Challenges in an Evolving Digital Landscape. In Corporate Governance and Sustainability: Navigating Malaysia’s Business Landscape; Alias, N., Yaacob, M.H., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 125–144. ISBN 978-981-97-7808-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Youssef, A.; Dahmani, M. Assessing the Impact of Digitalization, Tax Revenues, and Energy Resource Capacity on Environmental Quality: Fresh Evidence from CS-ARDL in the EKC Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, E.; Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Manresa-Marhuenda, E. Revolutionizing the Circular Economy through New Technologies: A New Era of Sustainable Progress. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Tax Administration 3.0: The Digital Transformation of Tax Administration 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/tax-administration-3-0-the-digital-transformation-of-tax-administration_ca274cc5-en.html (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- OECD. Global Outlook on Financing for Sustainable Development 2025. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/02/global-outlook-on-financing-for-sustainable-development-2025_6748f647/753d5368-en.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- OECD. OECD Economic Outlook. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/05/oecd-economic-outlook-volume-2024-issue-1_1046e564/69a0c310-en.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Matthijs, M. Hegemonic Leadership Is What States Make of It: Reading Kindleberger in Washington and Berlin. Rev. Int. Polit. Econ. 2022, 29, 371–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2024; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Heimberger, P. The New EU Fiscal Framework: Implications for Public Spending on the Green and Digital Transition; 2025. Available online: https://wiiw.ac.at/the-new-eu-fiscal-framework-implications-for-public-spending-on-the-green-and-digital-transition-dlp-7281.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Datta, P.M. Digital Transformation in a Globalized World. In Global Technology Management 4.0: Concepts and Cases for Managing in the 4th Industrial Revolution; Datta, P.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 227–260. ISBN 978-3-030-96929-5. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulos, G. Digital Plurilateralism in International Economic Law: Towards Unilateral Multilateralism? J. World Invest. Trade 2025, 26, 116–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Digital Transformation of Tax and Customs Administrations. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099448206302236597/pdf/IDU0e1ffd10c0c208047a30926c08259ec3064e4.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Puaschunder, J.M. Global Perspectives. In The Future of Resilient Finance: Finance Politics in the Age of Sustainable Development; Puaschunder, J.M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 103–151. ISBN 978-3-031-30138-4. [Google Scholar]

- Baghdasaryan, V.; Davtyan, H.; Sarikyan, A.; Navasardyan, Z. Improving Tax Audit Efficiency Using Machine Learning: The Role of Taxpayer’s Network Data in Fraud Detection. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 36, 2012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Shi, B.; Wang, J.; Dong, B. A Survey of Tax Risk Detection Using Data Mining Techniques. Engineering 2024, 34, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belahouaoui, R.; Attak, E.H. Digital Taxation, Artificial Intelligence and Tax Administration 3.0: Improving Tax Compliance Behavior—A Systematic Literature Review Using Textometry (2016–2023). Account. Res. J. 2024, 37, 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, N.; Sharif, A.; Ozturk, I.; Razzaq, A. How Do the Exploitation of Natural Resources and Fiscal Policy Affect Green Growth? Moderating Role of Ecological Governance in G7 Countries. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, A.; Manioudis, M.; Koskina, A. Τhe Political Economy of Green Transition: The Need for a Two-Pronged Approach to Address Climate Change and the Necessity of “Science Citizens”. Economies 2025, 13, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. G7 Toolkit for AI in the Public Sector. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/10/g7-toolkit-for-artificial-intelligence-in-the-public-sector_f93fb9fb/421c1244-en.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Shandilya, S.K.; Datta, A.; Kartik, Y.; Nagar, A. Navigating the Regulatory Landscape. In Digital Resilience: Navigating Disruption and Safeguarding Data Privacy; Shandilya, S.K., Datta, A., Kartik, Y., Nagar, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 127–240. ISBN 978-3-031-53290-0. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. The Future of European Competitiveness. 2024. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/97e481fd-2dc3-412d-be4c-f152a8232961_en?filename=The%20future%20of%20European%20competitiveness%20_%20A%20competitiveness%20strategy%20for%20Europe.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- World Bank. Global Trends in AI Governance. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099120224205026271/pdf/P1786161ad76ca0ae1ba3b1558ca4ff88ba.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- OECD. OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/2022/01/oecd-transfer-pricing-guidelines-for-multinational-enterprises-and-tax-administrations-2022_57104b3a.html (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- OECD. Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation of the Economy—Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two): Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/tax-challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-of-the-economy-global-anti-base-erosion-model-rules-pillar-two_782bac33-en.html (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- OECD. Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy—Administrative Guidance on the Global AntiBase Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two). December 2023. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/topics/policy-sub-issues/global-minimum-tax/administrative-guidance-global-anti-base-erosion-rules-pillar-two-december-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Xiao, C.; Tabish, R. Green Finance Dynamics in G7 Economies: Investigating the Contributions of Natural Resources, Trade, Education, and Economic Growth. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Chu, L.K.; Ghosh, S.; Diep Truong, H.H.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. How Environmental Taxes and Carbon Emissions Are Related in the G7 Economies? Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binyet, E.; Hsu, H.-W. Decarbonization Strategies and Achieving Net-Zero by 2050 in Taiwan: A Study of Independent Power Grid Region. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 204, 123439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baştuğ, S.; Akgül, E.F.; Haralambides, H.; Notteboom, T. A Decision-Making Framework for the Funding of Shipping Decarbonization Initiatives in Non-EU Countries: Insights from Türkiye. J. Shipp. Trade 2024, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, M.; Zöttl, G.; Grimm, V.; Becker, T.; Schober, M.; Zipse, O. Setting the Course for Net Zero. In Road to Net Zero: Strategic Pathways for Sustainability-Driven Business Transformation; Zipse, O., Hornegger, J., Becker, T., Beckmann, M., Bengsch, M., Feige, I., Schober, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 17–59. ISBN 978-3-031-42224-9. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Effective Carbon Rates 2023: Pricing Greenhouse Gas Emissions Through Taxes and Emissions Trading; OECD: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bartak, J.; Jabłoński, Ł.; Tomkiewicz, J. Does Income Inequality Explain Public Debt Change in OECD Countries? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 80, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexeev, M.; Zakharov, N. Who Profits from Windfalls in Oil Tax Revenue? Inequality, Protests, and the Role of Corruption. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 197, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Investigating the Effect of Income Inequality on Corruption: New Evidence from 23 Emerging Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 2100–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halili, B.L.; Rodriguez Gonzalez, C. The Contingent Effects of Economic Growth and Institutions on Income Inequality: An Empirical Study. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2025, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzana, A.; Samsudin, S.; Hasan, J. Drivers of Economic Growth: A Dynamic Short Panel Data Analysis Using System GMM. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altin, H. An Analysis of Global Stock Markets With the Autoregressive Distributed Lag Method. Int. J. Risk Conting. Manag. 2022, 11, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, R.I.; Alrasheedi, M.A.; Sadiq, R.; Aldawsari, A.M.A. Evaluating Predictive Accuracy of Regression Models with First-Order Autoregressive Disturbances: A Comparative Approach Using Artificial Neural Networks and Classical Estimators. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, H.E. Validity of Okun’s Law in a Spatially Dependent and Cyclical Asymmetric Context. Panoeconomicus 2022, 69, 447–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z. Ecological Well-Being Performance and Influencing Factors in China: From the Perspective of Income Inequality. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 1269–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, T.; Li, R. Does Artificial Intelligence Promote Green Innovation? An Assessment Based on Direct, Indirect, Spillover, and Heterogeneity Effects. Energy Environ. 2023, 36, 1005–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.T.; Xuan Hang, T.; Nguyen, Q.K. Tax Revenue-Economic Growth Relationship and the Role of Trade Openness in Developing Countries. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2213959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Satrovic, E. How Do Fiscal Policy, Technological Innovation, and Economic Openness Expedite Environmental Sustainability? Gondwana Res. 2023, 124, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Yanting, Z.; Guohua, N. Role of Environmentally Related Technologies and Revenue Taxes in Environmental Degradation in OECD Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 73283–73298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasim, A.; Nasir, M.A.; Downing, G. Determinants of Bank Efficiency in Developed (G7) and Developing (E7) Countries: Role of Regulatory and Economic Environment. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2024, 65, 257–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, U.F.; Rabiatu, K.; Wiredu, I. The Roles of ICT and Governance Quality in the Finance-Growth Nexus of Developing Countries: A Dynamic GMM Approach. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2025, 13, 2448228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Waris, U.; Qian, L.; Irfan, M.; Rehman, M.A. Unleashing the Dynamic Linkages among Natural Resources, Economic Complexity, and Sustainable Economic Growth: Evidence from G-20 Countries. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 3736–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipatnarapong, J.; Beelitz, A.; Jaafar, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Tax Avoidance: Evidence from BRICS Countries. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2025, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, P.; Wang, Y. Policy Tools for Sustainability: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Fiscal Measures in Natural Resource Efficiency. Resour. Policy 2024, 89, 104575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Xu, D.; Yuna, G.; Hussain, J.; Abbas, H.; Rafique, K. The Contribution of Resource-Based Taxation, Green Innovation, and Minerals Trade toward Ecological Sustainability in Resource-Rich Economies. Resour. Policy 2024, 93, 105092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, Z.; Zhang, Y. Role of Fiscal and Monetary Policies for Economic Recovery in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouni, M.; Mraihi, R.; Mrad, S.; El Montasser, G. Exploring the Dynamic Linkages Between Poverty, Transportation Infrastructure, Inclusive Growth and Technology: A Continent-Wise Comparison in Lower-Middle-Income Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lu, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Fang, S. The Impact of Executive Cognitive Characteristics on a Firm’s ESG Performance: An Institutional Theory Perspective. J. Manag. Gov. 2025, 29, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Y.T.; Nguyen Phong, N.; Le, T.B.N.; Thi Thu Hao, N. Enhancing Public Organizational Performance in Vietnam: The Role of Top Management Support, Performance Measurement Systems, and Financial Autonomy. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2024, 47, 1192–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, C.; Dincă, G. Public Sector’s Efficiency as a Reflection of Governance Quality, an European Union Study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291048. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund Fiscal Policies: World Revenue Longitudinal Database. 2024. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/fiscal-policies/world-revenue-longitudinal-database (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- World Bank Group. Interactive Data Access. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators/interactive-data-access (accessed on 9 March 2025).

- Hall, S.; Marisol, L.; Stuart, M.; O’Hare, B. Government Revenue, Quality of Governance and Child and Maternal Survival. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2022, 29, 1541–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe, O.; Tourek, G. How Can Lower-Income Countries Collect More Taxes? The Role of Technology, Tax Agents, and Politics. J. Econ. Perspect. 2024, 38, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasoiu, N.; Chifu, I.; Oancea, M. Impact of Direct Taxation on Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence Based on Panel Data Regression Analysis at the Level of Eu Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumasukun, M.; Noch, M. Comparative Analysis of Tax System Effectiveness in Developed and Developing Countries. Golden Ratio Tax. Stud. 2023, 3, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Ruch, F.U.; Skrok, E. Taxing for Growth: Revisiting the 15 Percent Threshold. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099062724151523023/p1778861e0c40b081186a61ced16cac6cde (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Gindelsky, M.; Moulton, J.; Wentland, K.; Wentland, S. When Do Property Taxes Matter? Tax Salience and Heterogeneous Policy Effects. J. Hous. Econ. 2023, 61, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecki, M.; Stähler, N. Labor tax reductions in Europe: The role of property taxation. Macroecon. Dyn. 2022, 26, 419–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Panda, P. What Ails Property Tax in India? Issues and Directions for Reforms. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, H.R.A.; Pinchbeck, E.W. How Do Households Value the Future? Evidence from Property Taxes. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2022, 14, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, J.W. An (in) Effective Tax and Expenditure Limit (TEL): Why County Governments Do Not Utilize Their Maximum Allotted Property Tax Rate. Public Adm. 2023, 101, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaqiri, V.; Elshani, A.; Ahmeti, S. The Effect of Direct and Indirect Taxes on Economic Growth in Developed Countries. Ekonomika 2024, 103, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascagni, G.; Dom, R.; Santoro, F.; Mukama, D. The VAT in Practice: Equity, Enforcement, and Complexity. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2023, 30, 525–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrera, M.; Corti, F.; Keune, M. Social Citizenship as a Marble Cake: The Changing Pattern of Right Production and the Role of the EU. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2023, 33, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lompo, A.A.B. How Does Financial Sector Development Improve Tax Revenue Mobilization for Developing Countries? Comp. Econ. Stud. 2024, 66, 91–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, F.; Vesan, P. From Austerity-Conditionality towards a New Investment-Led Growth Strategy: Social Europe after the Recovery and Resilience Facility. Soc. Policy Adm. 2023, 57, 513–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasundharam, V.; Basdevant, O.; Benicio, D.; Ceber, A.; Kim, Y.; Mazzone, L.; Selim, H.; Yang, Y. Fiscal Consolidations: Taking Stock of the Success Factors, Impact, and Design. IMF Work. Pap. 2023, 2023, A001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, A. The Effect of Foreign Direct Investment on Tax Revenue. Comp. Econ. Stud. 2023, 65, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Indicators | U.M | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaxRev | Tax revenue | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| TaxIncI | Taxes on income and profit of individuals | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| TaxIncC | Taxes on income and profits of corporations | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| TaxPro | Taxes on property | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| TaxSal | Taxes on sales and production | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| TaxTra | Taxes on international trade | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| TaxOth | Taxes not elsewhere classified | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| SocialCon | Social contributions | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| Grants | Grants revenue | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| RevOth | Other revenue | Percentage of GDP | International Monetary Fund [119] |

| RegQual | Regulatory quality | Percentile rank | World Bank Group [120] |

| ConCorr | Control of corruption | Percentile rank | World Bank Group [120] |

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaxRev | 24.473 | 4.439 | 15.11 | 30.914 |

| TaxIncI | 9.258 | 2.250 | 4.026 | 13.179 |

| TaxIncC | 2.851 | 0.863 | 1.309 | 5.813 |

| TaxPro | 2.55 | 1.162 | 0.57 | 4.484 |

| TaxSal | 8.987 | 2.928 | 4 | 12.596 |

| TaxTra | 0.097 | 0.109 | 0 | 0.398 |

| TaxOth | 0.425 | 1.349 | 0.001 | 16.091 |

| SocialCon | 10.993 | 4.999 | 4.466 | 19.016 |

| Grants | 0.074 | 0.121 | 0 | 1.019 |

| RevOth | 4.606 | 1.585 | 1.62 | 9.204 |

| RegQual | 161 | 1.366 | 0.335 | 0.49 |

| ConCorr | 161 | 1.411 | 0.517 | 0.01 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) TaxRev | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| (2) TaxIncI | 0.682 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| (3) TaxIncC | −0.010 | −0.298 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| (4) TaxPro | 0.234 | 0.096 | 0.192 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| (5) TaxSal | 0.764 | 0.228 | −0.151 | −0.181 | 1.000 | |||||||

| (6) TaxTra | −0.387 | 0.051 | 0.297 | 0.400 | −0.833 | 1.000 | ||||||

| (7) TaxOth | 0.186 | 0.218 | −0.165 | −0.313 | 0.234 | −0.239 | 1.000 | |||||

| (8) SocialCon | 0.049 | −0.349 | −0.161 | −0.425 | 0.488 | −0.612 | 0.142 | 1.000 | ||||

| (9) Grants | 0.274 | 0.328 | −0.233 | −0.599 | 0.395 | −0.399 | 0.388 | 0.296 | 1.000 | |||

| (10) RevOth | 0.475 | 0.635 | −0.111 | 0.307 | 0.045 | 0.194 | −0.076 | −0.110 | 0.064 | 1.000 | ||

| (11) RegQual | −0.044 | 0.128 | 0.110 | 0.254 | −0.201 | 0.206 | −0.429 | −0.418 | −0.371 | 0.271 | 1.000 | |

| (12) ConCorr | −0.177 | −0.134 | 0.250 | 0.293 | −0.259 | 0.252 | −0.437 | −0.248 | −0.404 | 0.243 | 0.816 | 1.000 |

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| TaxTra | 7.168 | 0.14 |

| TaxSal | 6.708 | 0.149 |

| TaxIncI | 6.072 | 0.165 |

| RegQual | 5.198 | 0.192 |

| ConCorr | 4.705 | 0.213 |

| SocialCon | 3.731 | 0.268 |

| RevOth | 3.311 | 0.302 |

| Grants | 2.638 | 0.379 |

| TaxPro | 2.633 | 0.38 |

| TaxIncC | 1.642 | 0.609 |

| TaxOth | 1.518 | 0.659 |

| Mean VIF | 4.12 |

| H0: All panels are stationary | Number of panels = 7 | |

| Ha: Some panels contain unit roots | Number of periods = 23 | |

| Time trend: Not included | Asymptotics: T, N -> Infinity sequentially | |

| Heteroskedasticity: Not robust LR variance: (not used) | ||

| Statistic | p-value | |

| TaxRev | 18.0761 | 0.0000 |

| TaxIncI | 14.6466 | 0.0000 |

| TaxIncC | 10.3486 | 0.0000 |

| TaxPro | 3.4833 | 0.0002 |

| TaxSal | 19.3309 | 0.0000 |

| TaxTra | 12.6403 | 0.0000 |

| TaxOth | 1.2477 | 0.0005 |

| SocialCon | 26.2667 | 0.0000 |

| Grants | 3.1758 | 0.0007 |

| RevOth | 3.9460 | 0.0000 |

| RegQual | 14.6586 | 0.0000 |

| ConCorr | 14.3960 | 0.0000 |

| TaxRev | Coef. | St.Err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf. Interval] | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TaxIncI | 1.044 | 0.020 | 52.34 | 0 | 1.004 | 1.083 | *** |

| TaxIncC | 1.119 | 0.027 | 41.41 | 0 | 1.066 | 1.172 | *** |

| TaxPro | 1.058 | 0.025 | 41.63 | 0 | 1.008 | 1.109 | *** |

| TaxSal | 1.095 | 0.016 | 68.01 | 0 | 1.063 | 1.127 | *** |

| TaxTra | 1.857 | 0.449 | 4.14 | 0 | 0.971 | 2.744 | *** |

| TaxOth | 0 | 0.017 | −0.02 | 0.988 | −0.033 | 0.033 | |

| SocialCon | 0.037 | 0.007 | 5.27 | 0 | 0.023 | 0.051 | *** |

| Grants | 0.172 | 0.245 | 0.70 | 0.483 | −0.312 | 0.656 | |

| RevOth | 0.167 | 0.021 | 8.01 | 0 | 0.126 | 0.209 | *** |

| RegQual | −0.504 | 0.124 | −4.07 | 0 | −0.748 | −0.259 | *** |

| ConCorr | −0.313 | 0.076 | −4.10 | 0 | −0.464 | −0.162 | *** |

| Constant | −1.16 | 0.236 | −4.91 | 0 | −1.627 | −0.693 | *** |

| Mean dependent var 24.473 | SD dependent var 4.439 | ||||||

| R-square 0.997 | Number of obs 161 | ||||||

| F-test 5391.372 | Prob > F 0.000 | ||||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) −4.413 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) 32.564 | ||||||

| TaxRev | Coef. | St.Err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf. Interval] | Sig | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | 0.017 | 0.014 | 1.25 | 0.213 | −0.010 | 0.044 | |

| L2 | 0 | 0.010 | −0.01 | 0.994 | −0.021 | 0.020 | |

| TaxIncI | 1.074 | 0.017 | 64.86 | 0 | 1.042 | 1.107 | *** |

| TaxIncC | 0.947 | 0.017 | 54.77 | 0 | 0.913 | 0.981 | *** |

| TaxPro | 0.985 | 0.029 | 33.57 | 0 | 0.927 | 1.042 | *** |

| TaxSal | 1.102 | 0.018 | 62.74 | 0 | 1.068 | 1.137 | *** |

| TaxTra | 0.978 | 0.196 | 4.98 | 0 | 0.594 | 1.363 | *** |

| TaxOth | −0.005 | 0.006 | −0.94 | 0.349 | −0.016 | 0.006 | |

| SocialCon | −0.047 | 0.012 | −3.80 | 0 | −0.071 | −0.023 | *** |

| Grants | −0.106 | 0.09 | −1.18 | 0.236 | −0.282 | 0.070 | |

| RevOth | 0.045 | 0.012 | 3.82 | 0 | 0.022 | 0.068 | *** |

| RegQual | 0.009 | 0.063 | 0.14 | 0.892 | −0.115 | 0.132 | |

| ConCorr | 0.057 | 0.062 | 0.92 | 0.356 | −0.064 | 0.179 | |

| Constant | −0.851 | 0.223 | −3.81 | 0 | −1.288 | −0.413 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 24.448 | SD dependent var | 4.441 | ||||

| Number of obs | 140 | Chi-square | 37998.012 | ||||

| Arellano-Bond test for AR(1) in first differences | z = −0.93 | Pr > z = 0.035 |

| Arellano-Bond test for AR(2) in first differences | z = −0.60 | Pr > z = 0.551 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fortea, C. Government Revenue Structure and Fiscal Performance in the G7: Evidence from a Panel Data Analysis. World 2025, 6, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030097

Fortea C. Government Revenue Structure and Fiscal Performance in the G7: Evidence from a Panel Data Analysis. World. 2025; 6(3):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030097

Chicago/Turabian StyleFortea, Costinela. 2025. "Government Revenue Structure and Fiscal Performance in the G7: Evidence from a Panel Data Analysis" World 6, no. 3: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030097

APA StyleFortea, C. (2025). Government Revenue Structure and Fiscal Performance in the G7: Evidence from a Panel Data Analysis. World, 6(3), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030097