Abstract

This study explores the factors influencing the willingness of Cashew Feni producers to adopt GI certifications, delving deeper into the behavioural factors. This study is guided by the extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. This study was conducted in Goa, India, from June 2024 to January 2025 using a quantitative approach. Face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaires were conducted with Cashew Feni producers actively producing, processing, and distributing Feni in the key production regions. A total of 200 producers were approached, and after validation, 148 responses were considered valid for analysis. The respondents were chosen using a stratified random sampling method. This study employed Partial Least Squares-based Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) in the SmartPLS 4 software to analyse the data. This study found that attitude is a strong predictor significantly driving adoption. Perceived economic benefits also impact attitudes and directly affect the willingness to adopt GIs, emphasising the role of economic factors. Additionally, awareness influences attitudes and subjective norms, indicating that informed producers are likelier to have a positive attitude towards GI adoption. This study also found a significant impact of subjective norms on attitudes and perceived behavioural control. These insights can assist policy formulation and boost sustainable growth and cultural preservation.

1. Introduction

The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) defines a geographical indication (GI) as ‘a sign used on products that have a specific geographical origin and possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that origin. To function as a GI, a sign must identify a product originating in a given place’. A GI helps identify a product’s unique origin, safeguard its authenticity, protect traditional producers’ rights, and enhance the market reputation for increased revenue [1]. It is a form of an intellectual property right (IPR) that protects the name of a product linked to its place of origin [2]. Unlike trademarks that distinguish a brand, a GI tag protects the name of a product that is deeply associated with its place of origin. This ensures that only authorised producers from the designated region can legally use the name, preventing imitation and preserving authenticity [3].

By 2025, India registered 655 products with GI tags, including 10 from Goa [4]. In 2009, Cashew Feni (an alcoholic beverage crafted from cashew apples using time-honoured traditional techniques) became the first Indian alcoholic beverage to receive GI tagging. The name ‘Feni’ finds its origin in the Sanskrit word ‘Phena’, which means froth or foam, describing its bubbly appearance during distillation. This spirit is traditionally produced through the natural fermentation and earthen pot distillation of cashews, reflecting the cultural significance and artisanal practices [5]. Unlike other parts of India, where alcohol consumption carries a social stigma, this beverage is celebrated and embraced as the cultural emblem of hospitality and togetherness in Goa [6]. It enjoys broad social acceptance and is a main attraction at festivals, weddings, and community gatherings, strengthening social bonds. Beyond its role in festivities, locals also attribute medicinal value to Feni, using it as a traditional remedy for colds or as a natural antiseptic [5].

In 2016, the Goa Government recognised Feni as the ‘Heritage Spirit of Goa’ [7], giving it a special status and acknowledging its deep connection to Goa’s land and traditions, similar to Champagne from France or Scotch from Scotland [8]. The GI tag was a significant milestone in protecting Feni’s unique identity, ensuring its quality and facilitating its access to premium markets [9]. The Government of Goa has set up a Conformity Assessment Board (CAB) to help producers meet GI guidelines and effectively use the GI tag [10,11]. It certifies products for GI labelling, monitors quality and origin criteria, and provides technical support and training. The CAB also addresses misuse and disputes, helping maintain the authenticity of GI products. Through these functions, it strengthens the producer capacity, ensures regulatory compliance, and enhances market credibility.

The Goan Cashew Feni market has not yet fully capitalised on the benefits of the GI tag, which protects the product’s identity, boosts market value, and preserves traditional methods [12]. Official reports from the state’s Agriculture Department indicated that cashew production in certain regions in Goa dropped by up to 50% in 2024, leading to a shortage of raw materials and increased costs [13]. While GI protection could boost the market reach and value, low awareness, weak branding, and counterfeiting limit its economic benefits. The legal challenges further hinder its adoption, including a lack of legal certainty, ineffective awareness programmes, difficulties in GI registration, and limited financial resources. Additionally, the Goan Cashew Feni industry faces growing threats from climate change, declining cashew yields, and rising production costs, all of which jeopardise its long-term sustainability despite GI recognition.

Several researchers have noted that despite strong legal frameworks, GI adoption is hindered by weak enforcement, high registration costs, unclear standards, low awareness, and poor stakeholder coordination [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. These challenges arise when global markets show a growing interest in craft spirits, an industry projected to expand significantly in the coming years [22]. Despite the challenges, if producers fully capitalise on the advantages of the GI tag, enhance their marketing strategies, and adapt to evolving conditions, Cashew Feni has the potential to become a globally recognised spirit. This transformation would protect the livelihoods of the Cashew Feni producers in Goa and preserve an essential aspect of the region’s cultural heritage. Furthermore, the GI tag protects against counterfeit products, ensuring that only those who adhere to traditional methods and originate from Goa can rightfully use this prestigious label. Therefore, this emphasises the urgent need for sustainable practices and innovative strategies to ensure the future of Feni [23].

Acquiring a GI enhances the commodity’s appeal in domestic and international markets, boosting consumer confidence in its authenticity and uniqueness, which helps producers distinguish their products [24]. The GI will positively impact pricing strategies for goods, supporting traditional production methods amidst monopolistic competition and contributing to regional economic progress [25]. The benefits of GIs’ extend beyond individual producers, contributing to regional economic development [26,27]. Recognising a product’s geographic origin often stimulates tourism, promotes local industries, and creates employment opportunities, fostering sustainable economic growth [28]. Studies have highlighted that adopting a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) could protect indigenous products, enhance global quality perceptions, and promote economic stability and rural development [16,29,30,31], which can contribute towards the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices [32,33,34,35] and environmental conservation [36].

GI tags help producers secure premium prices, wider market access, and cultural preservation, contributing to local economic growth via tourism and employment [9]. However, divergent viewpoints exist in the literature. For instance, Curzi & Huysmans [37] emphasised the primacy of international trade protections over localised behavioural factors, suggesting that macro-level institutional arrangements might outweigh individual attitudes or social influence. Likewise, Wang et al. [38] argued that GI certification does not necessarily translate into changes in consumer perception, which complicates the assumption that increased awareness and perceived economic benefits invariably lead to adoption. Hence, adopting a GI is crucial for success, as it fosters economic growth, cultural preservation, and sustainability. However, its implementation depends on producers’ motivations and supportive conditions. Therefore, this study examines the various factors, such as attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, awareness, and perceived economic benefits, that influence Goan Cashew Feni producers’ willingness to adopt GI certification.

In this regard, the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)—which offers a valuable framework for understanding the psychological determinants that influence individuals’ decision-making processes, particularly in the context of adopting new practices or innovations—is considered the basis of this study. According to the TPB, an individual’s willingness or intention to perform a behaviour is shaped by three core components: their attitude toward the behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. However, this study expands the TPB by exploring two more constructs, i.e., the awareness of GI benefits and perceived economic advantages, which also play a role in shaping producers’ willingness to adopt GI certification. By investigating these elements, this research aims to provide a nuanced understanding of the behavioural motivations and barriers within the Feni-producing community, ultimately contributing to more strategic and effective policy interventions and capacity-building efforts to enhance GI adoption.

The structure of this paper is organised as follows. Section 1 deals with the introduction. The conceptual framework is summarised in Section 2. The materials and methods used in the study are detailed in Section 3. Section 4 presents the results of the data analysis. Section 5 discusses the results. Implications of this study are discussed in Section 6. And finally, Section 7 includes the conclusions drawn from this study and limitations of the work and also discusses the scope for future research.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Willingness to Adopt GI Certification

Understanding the willingness of producers to adopt GI tags requires a structured analysis of behavioural intentions, and the TPB, developed by Ajzen [39], serves as a foundational framework for this purpose. Although the TPB is the primary theoretical lens for this study, previous studies have also adopted other theories to explore the willingness to adopt GI tagging. One such theory is the Expected Utility Theory. It is a theory that explains how individuals make choices when faced with uncertainties. Studies such as [40] used the Expected Utility Theory to provide a rational choice perspective, suggesting that producers evaluate the expected benefits of GI tag adoption, such as improved market access, premium pricing, and brand recognition, against perceived risks or costs. This theory aligns with the attitudinal component of the TPB but introduces a cost–benefit evaluation framework.

Similarly, the Theory of Competition and Resource Advantage has also been adopted by some researchers in the GI adoption context. This theory as discussed by [41] and explains how competitive pressure can influence adoption decisions. In a similar context, some studies have adopted the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in their studies to explore the factors influencing the adoption of GIs. The TAM postulates that the willingness to adopt a new system or concept is driven by two primary beliefs: the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. While the TAM focuses on technology adoption and user acceptance, the TPB provides a broader lens for understanding behavioural intentions. This has been demonstrated by several studies. For instance, refs [42,43,44] utilised the TPB to analyse the willingness of Indonesian coffee farmers to adopt GI standards. Moreover, on the contrary, some studies such as [45,46] used a non-conventional approach for studying farmers’ attitudes towards GI standards by not relying on the classical behavioural theories and focusing on new psychological aspects and motivators. These studies identified perceived economic benefits and behavioural control as the key determinants and indicated that producers may adopt GI tags not solely for personal or social reasons but to remain competitive when peers begin to benefit from such practices.

Therefore, the model proposed in this study is based upon many of the key factors identified by these researchers as strong predictors of adoption behaviour. Although all the above-mentioned theories and models are not directly applied in the current research, they underscore the value of integrating behavioural, economic, and strategic dimensions to develop a more holistic understanding of GI adoption behaviour. Hence, this study combines the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) with elements from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Expected Utility Theory to develop a model which can better explain the factors influencing the willingness of Cashew Feni producers to adopt GI certification.

2.2. Perceived Economic Benefits of GI Adoption

The economic benefits of GI adoption have been a central component of many research studies in recent years. GI adoption is known to benefit the producers in many ways, by enhancing market access for producers, improving the value distribution, supporting price increases, and contributing to resilient value chains and market diversification [47]. These benefits are ultimately likely to enhance producers’ economic welfare and result in increased profitability for producers.

This perceived positive economic impact of GI adoption has been supported by many researchers in their studies. For instance, ref. [48] analysed the European wine and olive sectors and concluded that farms with GIs significantly outperform non-GI farms in terms of income. Similarly, ref. [29] highlighted the role played by Protected Geographical Indications (PGIs) in enhancing the market competitiveness and economic stability for Kenyan tea. Likewise, ref. [49] demonstrated how GI certification leads to premium pricing and the boost of farmer incomes in case of Koerintji cinnamon.

In a similar context, ref. [50] emphasised the economic advantages of GI-tagged rice varieties in Kerala, India. However, there are certain studies whose findings contradict the understanding that GI adoption can impact producers positively. For instance, refs [51,52] found that GI-labelled products earn a lower price than non-GI tag products. Similarly, ref. [53] emphasised that although GI participation increases profits and reduces costs, it has slightly reduced the land productivity for small-scale Arabica coffee farmers. These studies show that the economic benefits of GI adoption have been widely explored by many researchers. However, there seem to be limited studies that have explored whether the perceived economic benefits of GI can drive the adoption of GI certification among producers. The importance of exploring this dimension has been reiterated by [42], who identified perceived economic benefits as a critical driver of GI adoption among agricultural producers. Moreover, studies have also emphasised that a positive attitude may also stem from perceived economic or reputational benefits. Therefore, we hypothesise the following.

H1.

The perceived economic benefits of GI certification significantly influence the attitude of producers toward GI certification.

H2.

The perceived economic benefits of GI certification significantly influence the willingness of producers to adopt GI certification.

2.3. Awareness of GI Tags

The awareness of GI tag adoption has been a subject of exploration in many recent studies. Several studies such as [22,54,55,56] underscored the deficit in awareness among producers regarding the benefits of GIs in India, advocating for structured training and educational programmes to bridge the knowledge gap.

Awareness has been identified as a key driver of adoption by research studies in the context of GIs [57]. For instance, ref. [58] analysed the expectations of Croatian producers and linked enhanced awareness and education with GI adoption. Similarly, ref. [59] emphasised the critical role of farmer awareness in enhancing the adoption of GI-tagged Guntur Sannam chilli in India. Likewise, ref. [32] highlighted that a greater awareness of GIs and institutional support can promote sustainable practices among farmers. In addition, some studies, such as [60], found that a low GI awareness, weak enforcement, and limited legal action against counterfeits resulted in traders benefiting more than producers.

Although many studies highlight the lack of awareness about GI and its benefits among producers, there are limited studies which link this aspect to the behavioural factors and producers’ willingness to adopt GIs to examine the underlying impact. Studies such as [51] also highlight the pivotal role of awareness in driving adoption and emphasise the need to establish a direct link between producers’ awareness of GI practices and their willingness to adopt them. Therefore, we hypothesise the following.

H3.

The awareness of GI certification significantly influences producers’ attitudes toward GI certification.

H4.

The awareness of GI certification significantly influences the subjective norms of producers.

H5.

The awareness of GI certification significantly influences the perceived behavioural control of producers.

H6.

The awareness of GI certification significantly influences the willingness of producers to adopt GI certification.

2.4. Attitude, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Behavioural Control

Intention, an individual’s motivation or willingness to engage in a particular behaviour, is central to Ajzen’s TPB [39]. The TPB proposes that behavioural intention, the immediate predictor of action, is influenced by three constructs: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. Attitude reflects the individual’s positive or negative evaluation of the behaviour. Subjective norms capture the perceived social pressure from important referents to perform or not perform the behaviour. Perceived behavioural control refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour, akin to self-efficacy. It reflects a producer’s confidence in managing the process of the GI registration. Several empirical studies have successfully applied the TPB in the context of adoption behaviour. For instance, ref. [61] found attitude and perceived behavioural control to be significant predictors of agroforestry adoption behaviour. Likewise, several studies such as [62,63,64] tried to extend the TPB in order to examine farmers’ adoption behaviour in lower to middle-income countries.

Although the TPB has been widely used in the context of GI adoption, contrasting findings in the previous research underscore the complexity of GI adoption behaviour. While internal factors such as attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control are identified to be instrumental by many studies, researchers have highlighted that external dynamics, like market access, regulatory frameworks, and consumer demand, may also shape producers’ decisions. Due to the complexity involved in studying the willingness regarding GI adoption, this study primarily concentrates on the behavioural aspects of adoption at the producer level. Contemporary research suggests that integrating elements from multiple theoretical models yields a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the behavioural intention and adoption behaviour [43,65,66,67]. Building upon this approach, the current study proposes a conceptual framework that integrates key constructs from the TPB and combines it with specific variables from the TAM and Expected Utility Theory to examine the drivers of producers’ willingness to adopt GI certification. Therefore, we hypothesise the following.

H7.

Subjective norms significantly influence the attitude of producers toward GI certification.

H8.

Subjective norms significantly influence the perceived behavioural control of producers.

H9.

The attitude toward GI certification significantly influences the willingness of producers to adopt GI certification.

H10.

Subjective norms significantly influence the willingness of producers to adopt GI certification.

H11.

Perceived behavioural control significantly influences the willingness of producers to adopt GI certification.

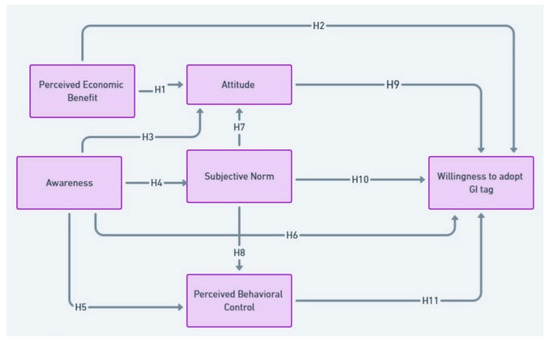

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model developed in this study. The model hypothesises that traditional TPB constructs along with perceived economic benefits and the awareness of GI certification influence the willingness to adopt GI tags.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of this study based on previous studies.

An in-depth review of existing studies enabled the researchers to identify key statements that can be used to measure the constructs of this study’s conceptual model. Table 1 shows the previous research works reviewed to identify the variables.

Table 1.

Constructs used in the model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

This research was conducted in Goa, India, which is known for its rich heritage and traditional Cashew Feni production. Cashews, native to Brazil, were introduced to India by the Portuguese in the 16th century for soil conservation and thrived in regions like Kerala, Goa, and Karnataka [116]. In Goa, cashews were introduced in 1570 to prevent soil erosion [117]. Over time, local communities began to ferment the cashew apple, creating traditional beverages such as Urrak and Feni. This unique spirit is made from cashew apples, a practice deeply rooted in the state’s culture. According to official records of the Directorate of Agriculture in the state, Goa has over 55,000 hectares of cashew cultivation, producing high-quality cashew nuts and apples used to produce Feni, a traditional distilled spirit that has been integral to the region’s culture for centuries. According to the Directorate of Agriculture and the Government of Goa, the state has over 55,000 hectares dedicated to cashew cultivation, making it a significant player in both the horticultural economy and the traditional liquor industry. Beyond its role in the beverage industry, cashew farming contributes to employment, rural enterprises, and agritourism, offering multiple pathways for sustainable development.

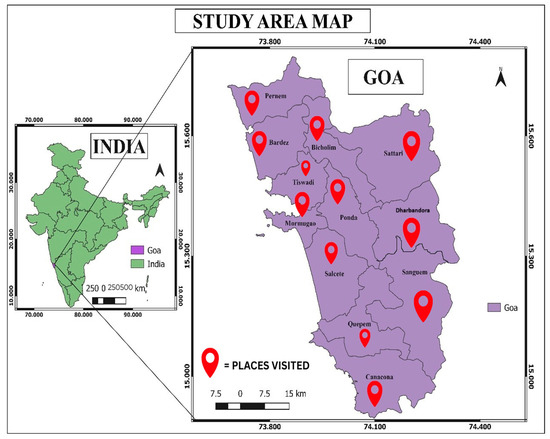

This study focuses on Goa as a geographically and culturally appropriate site for investigating producer perceptions of GIs, particularly concerning Cashew Feni. By examining the interplay between awareness, attitude, perceived economic benefits, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and willingness to adopt and support GI-tagged products, this research aims to assess the impact of GI certification on traditional industries. Figure 2 illustrates the geographical landscape of the study area, highlighting key cashew-growing regions and Feni-producing localities, which form the socio-economic context for this investigation.

Figure 2.

The study area.

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

The data for this study were collected through field visits to key Cashew Feni-producing regions across the state of Goa, ensuring first-hand interactions with local producers. To capture authentic insights and improve response accuracy, a face-to-face interview was conducted using a structured questionnaire. The data collection period spanned from June 2024 to March 2025, allowing sufficient time for thorough engagement with local producers and accommodating seasonal variations in production activities. The sampling distribution was performed based on the total population in the study area. It was noted that, as of March 2025, Goa had approximately 750 registered Cashew Feni producers. Given the geographical dispersion and the diversity of producers, ranging from small-scale, traditional distillers to larger, commercially oriented enterprises, it was decided that the questionnaire would be distributed across Goa.

A stratified random sampling method was employed to ensure a broad and representative coverage across the state. To implement stratification effectively, the 12 talukas of Goa were used as strata, allowing for a proportional representation from each region. This approach ensured that the sample reflected the regional diversity in Feni production, accounting for differences in local practices, the scale of operations, and levels of engagement with the GI certification process. Reaching respondents posed logistical challenges, particularly because many Feni producers operate in remote and rural areas with limited accessibility. However, the stratified sampling method helped overcome these challenges by enabling systematic outreach and ensuring coverage across all strata. Moreover, the field researchers leveraged existing local networks, including agricultural cooperatives, community leaders, and regional industry associations, to establish trust and a rapport with potential participants.

The structured questionnaire was distributed among 200 GI-certified and non-GI-certified Cashew Feni producers in Goa. Out of the 200 producers approached, 148 provided valid and complete responses, resulting in a response rate of 74%. This balanced sample was crucial for examining the broader socio-economic and perceptual landscape of the Feni industry in Goa. The decision to approach 200 respondents for this study was guided by a combination of practical, methodological, and statistical considerations. While the total population of registered Cashew Feni producers in Goa is approximately 750, this study aimed to collect data from a representative, which could provide reliable and generalisable insights within the constraints of the time, geography, and resources. From a methodological and statistical standpoint, the final sample of 148 valid responses met the minimum sample size requirements for Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), which prioritises quality over quantity and requires an adequate sample to ensure statistical power. Thus, the choice of 200 respondents struck a balance between fieldwork feasibility and the need for reliable, generalizable findings.

This study utilises a structured, two-part questionnaire. The first section gathers respondents’ socio-demographic information, such as age, experience, education, and location. The second section assesses factors affecting GI adoption through the TPB framework, focusing on the awareness, attitude, social norms, perceived benefits, and willingness to adopt. The questions are carefully formulated to ensure clarity and relevance, using precise and straightforward language to facilitate accurate responses. The questionnaire was translated into Goa’s regional language, Konkani, to accommodate respondents from diverse linguistic backgrounds. Closed-ended questions using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates strong disagreement and 5 indicates strong agreement, were included to ensure consistency and the ease of the statistical analysis. The Likert scale is widely used by researchers to measure responses through questionnaires and is identified to be an effective scale due to its simplicity and clarity [12,18]. The survey is structured to respect respondent privacy, encouraging honest participation while generating reliable insights into the factors influencing producers’ willingness to adopt GI certification.

3.3. Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), a statistical technique suitable for exploratory research and small sample sizes [118], which provided insights into complex relationships between multiple latent variables. Therefore, PLS-SEM is a suitable alternative for covariance-based SEM, which allows for the construction and estimation of a particular model without considering highly restrictive constraints [118,119,120,121]. Since the sample of this study is limited in size, PLS-SEM as a data analysis technique was most suitable. The analysis followed a two-step approach: first, assessing the outer model for reliability, validity, internal consistency, and discriminant validity and second, conducting a model fit analysis using the Tenenhaus Goodness-of-Fit (GoF) criterion [119] to evaluate the explanatory power. PLS-SEM with Smart PLS 4 software was adopted to analyse the data and address this study’s hypotheses. Two steps of measurement were taken into account to test the hypotheses. The first step involved assessing the outer model, including measuring the indicator’s reliability, convergent validity, internal consistency, and discriminant validity. Secondly, the model’s overall fit was measured using the Tenenhaus GoF criterion [122]. The SEM model developed in this study, illustrated in Figure 1, positions the willingness to adopt the GI tag as an endogenous latent variable influenced by the perceived economic benefits, attitude toward GI certification, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and awareness of GI certification.

4. Results

4.1. The Demographic Profiling of the Respondents

The data shown in Table 2 indicates that the Feni production industry in Goa is predominantly managed by older, experienced individuals, with minimal participation from younger generations, potentially impacting the sector’s long-term sustainability. The sample comprised 51.35% of respondents from the North Goa district and 48.65% of respondents from the South Goa district, highlighting that the sample was spread across the state with significant representation from both the districts of the state. Goan Feni production is highly dominated by the male population, and therefore all the respondents of this study were men. The sample of this study consisted of 75% of respondents aged more than or equal to 45 years, with 45.27% of respondents aged more than or equal to 55 years. In contrast, individuals below 35 account for only 14.86%, highlighting a significant gap in youth engagement. This suggests that the traditional Feni business remains mainly in the hands of the older generation, with limited succession from younger individuals.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of demographic profile.

The Feni industry heavily depends on seasoned producers, with 76.35% of respondents having over 15 years of experience and another 9.46% possessing 11–15 years of expertise. Notably, no respondents had less than a year of experience, indicating a lack of new entrants into the field. This suggests that Feni production remains a tradition upheld by long-established producers, with minimal participation from newcomers. The absence of fresh entrants could challenge the industry’s sustainability and future growth, as knowledge transfer and generational continuity appear limited.

4.2. Models of Measurement and Evaluation

The results of the measurement model, which assessed the reliability, validity, and appropriateness of the data for subsequent Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), are presented in Table 3. Six latent constructs—attitude awareness, willingness to adopt GI tag, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, awareness, and perceived economic benefit—were assessed to determine the willingness to adopt the GI tag (Appendix A). Each construct was measured using multiple observed variables. During the validation of the measurement model, reliability and validity were confirmed by examining outer loadings and multicollinearity values. However, several items were found to fall below the recommended thresholds, specifically outer loadings below 0.70 and Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values exceeding 5, indicating issues with the individual item reliability and potential multicollinearity. Therefore, due to such reasons, certain variables, such as AW1, AW5, AW6, and AW8 from the awareness construct; AT1, AT2, and AT4 from the attitude construct; SN4, SN5, and SN6 from the subjective norms construct; PBC1, PBC5, PBC6, and PBC7 from the perceived behavioural control construct; PEB3, PEB5, PEB6, and PEB7 from the perceived economic benefits construct; and WTA6, WTA7, and WTA8 from the willingness to adopt construct, were excluded from the final model. In order to ensure validity and reliability, the researchers carefully assessed the variables before deletion. This process firstly involved an initial model estimation with all items retained. This was followed by checking the outer loadings of each variable to identify those with smaller loadings (<0.7). The next step involved the one-by-one removal of indicators with low outer loadings, while carefully observing their impact on the AVE and CR. This process was repeated iteratively, and indicators whose removal improved the AVE and CR values were excluded from the final model. Thereafter, the model was re-estimated and the R2 values, path coefficients, and model fit indices were assessed.

Table 3.

Construct reliability, validity, outer loading, and VIF.

All loadings (λ) of items retained in the model exceeded the minimum acceptable threshold of 0.70 and were statistically significant at p < 0.000 [123], confirming the adequacy of the indicator reliability. The outer loadings ranged from 0.714 to (PBC2) to 0.942 (SN2).

The construct reliability was validated through Cronbach’s alpha (α) and the composite reliability, with all constructs meeting the recommended threshold limit of 0.70 [121], indicating satisfactory internal consistency. The values of Cronbach’s alpha (α) ranged from 0.717 (PEB) to 0.900 (SN). Likewise, the values of the composite reliability (CR) ranged between 0.824 (PEB) and 0.937 (SN).

Next, the convergent validity was confirmed, with Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values ranging from 0.611 (PEB) to 0.833 (SN), all above the 0.50 benchmark, thus verifying that constructs adequately capture the variance of their indicators.

Furthermore, multicollinearity was examined using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with all indicators falling below the critical threshold of five, confirming the absence of collinearity issues. The VIF values ranged between 1.394 (AT3) and 4.107 (SN2). In addition to these, cross-loadings were checked for all constructs to ensure the reliability and validity of the items retained in this study. It was observed that the items had no issues of cross-loading. Overall, the measurement model demonstrated robust psychometric properties, supporting its application in further hypothesis testing. The reliability and validity results lend empirical credibility to the model, providing a sound theoretical foundation to investigate the determinants of Cashew Feni producers’ willingness to adopt GI practices in Goa.

Table 4 assesses the discriminant validity through the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, as recommended by [124]. HTMT values should ideally be below 0.85 or 0.90, indicating that each construct measures a distinct concept.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity using HTMT and FLC.

The correlation (r) matrix highlights the relationships among key constructs influencing Cashew Feni producers’ willingness to adopt GI practices. Willingness shows the strongest positive correlation with the ‘perceived economic benefit’ (r = 0.787), followed by ‘attitude’ (r = 0.761), and ‘perceived behavioural control’ (r = 0.425), indicating that economic gains, favourable attitudes, and confidence in one’s ability are major drivers of GI adoption. ‘Subjective norms’ (r = 0.282) and ‘awareness’ (r = 0.153) have weaker associations with ‘willingness’, suggesting social influence and awareness alone may not strongly motivate adoption. Strong inter-construct relationships, such as between ‘attitude’ and ‘perceived economic benefit’ (r = 0.523) and between ‘attitude’ and ‘perceived behavioural control’ (r = 0.549), further confirm the importance of personal beliefs and perceived benefits. Overall, the results underscore that economic incentives and individual motivation are more influential than social or informational factors in promoting GI adoption.

Table 4 also exhibits discriminant validity, which was evaluated using the Fornell and Larcker Criterion, ensuring that each construct was distinct. The square root of the AVE for each construct exceeded the inter-construct correlation values, satisfying the criteria.

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

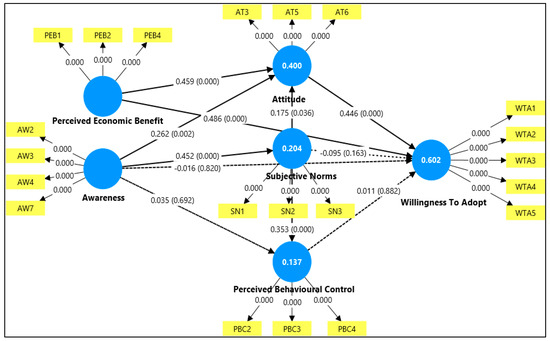

Table 5 presents the hypothesis test results, showing standardised path coefficients that indicate the significance of relationships among latent variables. Figure 3 illustrates this study’s findings.

Table 5.

Testing of the hypotheses.

Figure 3.

Graphical output of PLS-SEM using primary data in SmartPLS 4.

The structural model was assessed using Smart-PLS to test the hypothesised relationships among key latent constructs influencing Cashew Feni producers’ willingness to adopt GI practices in Goa. Seven of the eleven hypotheses were found to be statistically significant and supported. In contrast, four hypotheses were unsupported as they did not achieve statistical significance. Specifically, the results demonstrate that perceived economic benefits have a substantial influence on the attitude toward GI certification (β = 0.459, σ = 0.075, t = 6.113, p = 0.000) and willingness to adopt GI certification (β = 0.486, σ = 0.076, t = 6.408, p = 0.000). Hence H1 and H2 were supported. The results also support H3 and H4, indicating that awareness significantly affects attitudes (β = 0.262, σ = 0.083, t = 3.170, p = 0.002) and subjective norms (β = 0.452, σ = 0.070, t = 6.449, p = 0.000). However, the results show an insignificant impact of awareness on the perceived behavioural control and willingness to adopt GI certification, resulting in the rejection of H5 and H6, respectively. These non-significant results suggest that while awareness might be critical, it may not directly translate into perceived behavioural control or actionable intent without adequate institutional facilitation.

Furthermore, this study found that subjective norms significantly influence both attitudes (β = 0.175, σ = 0.083, t = 2.101, p = 0.036) and perceived behavioural control (β = 0.353, σ = 0.095, t = 3.725, p = 0.000), hence supporting H7 and H8. In the case of H9, attitude is found to significantly influence the willingness to adopt GI certification (β = 0.446, σ = 0.060, t = 7.409, p = 0.000), resulting in its acceptance. However, in the case of H10 and H11, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control are found to have insignificant impacts on the willingness of producers’ to adopt GI certification. These findings align with the theoretical underpinnings of the Theory of Planned Behaviour, indicating that cognitive evaluations and normative pressures are central to shaping producers’ behavioural intentions.

The SEM output in Figure 3 shows the key factors influencing producers’ willingness to adopt the GI tag. The model reveals that attitude is a strong predictor of willingness (β = 0.446, p = 0.000), suggesting that a favourable outlook toward the GI tag significantly drives adoption. Similarly, perceived economic benefits strongly impact attitudes (β = 0.459, p = 0.000) and directly affect the willingness to adopt GI certification (β = 0.486, p = 0.000), highlighting the importance of economic considerations in the decision-making process. Likewise, awareness significantly influences attitudes (β = 0.262, p = 0.002) and subjective norms (β = 0.452, p = 0.000), indicating that informed producers are more likely to develop positive attitudes and feel social encouragement. Moreover, subjective norms strongly impact attitudes (β = 0.175, p = 0.036) and perceived behavioural control (β = 0.353, p = 0.000). However, subjective norms (β = −0.095, p = 0.163) and perceived behavioural control (β = 0.011, p = 0.882) do not significantly influence willingness, suggesting that social pressure and perceived control over adoption are not strong motivators. Similarly, awareness does not significantly affect perceived control and ultimately has an insignificant impact on the willingness to adopt GI certification.

Assessing the structural model also involves the evaluation of the R-squared values of the dependent variables to identify the explanatory power of the model. In this case, the model has four endogenous constructs, including attitudes (R2 = 0.400), subjective norms (R2 = 0.204), perceived behavioural control (R2 = 0.137), and the willingness to adopt (R2 = 0.602). R2 refers to the amount of variance explained by the explanatory variables. In this study, the ultimate dependent variable of the ‘willingness to adopt’ has a fairly good R2 value, indicating the explanatory power of the model proposed. Overall, the findings underscore that awareness is key to strengthening positive attitudes, and economic benefits and positive attitudes ultimately enhance the willingness of producers to adopt GI tagging practices.

5. Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing the adoption of GI certification among Cashew Feni producers in Goa. Employing the extended TPB framework, the results of the structural model reveal several important insights into the factors influencing the willingness to adopt GI certification. The findings underscore the importance of perceived economic benefits, which showed a strong and statistically significant positive effect on attitudes and the willingness to adopt GI certification. The results presented by [43] have shown that perceived economic benefits significantly influence the willingness to adopt GI certification; however, they do not support the impact of PBC on attitudes. Thus, this study partially supports [43]. Thus, this study contributes to expanding the TPB framework by significantly explaining the relationship between perceived economic benefits, attitudes, and the willingness to adopt GI certification. Thus, this study revealed that when producers associate GI certification with economic advantages, such as premium pricing, market differentiation, brand protection, and legal safeguards, they are more likely to form favourable attitudes toward certification. The strong relationship between the perceived economic benefit and attitude reinforces that economic incentives are critical motivators for adoption. Similar patterns have been observed in studies on Thai Jasmine rice [125], Robusta coffee farmers in Indonesia [33], and Kerala rice farmers [50]. Similarly, perceived economic benefits directly affect the willingness to adopt GI certification, suggesting that economic considerations shape attitudes and are crucial to drive certification adoption. This study found that access to information about the economic benefits of GI certification was a significant determinant of adoption and willingness, suggesting that perceived benefits play a crucial role [125,126]. Thus, this study revealed that the perceived economic benefit and attitude are the strongest predictors of willingness.

Similarly, it is observed that awareness had a significant positive influence on attitudes and subjective norms. The present study contradicts the result produced by [43], who reported that no significant relationship exists between farmers’ knowledge or awareness and attitudes. Thus, this study has made an additional contribution in identifying the significant positive influence of awareness on attitudes and subjective norms, indicating that as individuals become more informed or knowledgeable about the behaviour, they tend to view it more positively and also feel that others around them expect or support the behaviour. However, in the present study the awareness did not significantly and directly affect perceived behavioural control and the willingness to adopt GI certification. In this regard, ref. [43] has argued that farmers’ knowledge significantly and positively affects PBC, which implies that the higher the level of farmers’ knowledge about the GI concept, the greater the effect on perceived behaviour control. Thus, the current study does not support the arguments of [43] and indicates that increased knowledge about GI certification does not necessarily boost confidence in navigating the certification process. This underscores the importance of addressing structural barriers, such as streamlining procedures, reducing costs, and providing institutional support, to enhance producers’ confidence and motivation to adopt GI certification. Although the limited adoption of GI tags by producers may be partly due to factors such as low awareness and the complexity of the certification process, the lack of adequate support from relevant authorities appears to be a more significant barrier to adoption [127]. This highlights the importance of improved and simplified registration procedures and capacity-building initiatives [105]. By addressing these barriers, more producers can be encouraged to pursue GI certification, ultimately unlocking its full potential to produce economic, cultural, and social benefits [26]. Consequently, the findings imply that policy efforts to enhance the adoption of GI certification should not only target attitudinal and normative shifts but also address systemic constraints to strengthen producers’ perceived behavioural control.

The results also showed that extending the relationship between subjective norms and attitudes and perceived behavioural control in the TPB model has resulted in a positive effect, which is also aligned with [43,128]. The influence of subjective norms on attitudes suggests that peer influence and community norms are pivotal in shaping producers’ perceptions of GI certification. Producers who perceive strong support or approval from their industry peers and community are more likely to form favourable attitudes toward GI certification. This observation underscores the potential of social influence for promoting positive perceptions of certification. Findings from the Indonesian coffee sector similarly suggest that subjective norms and attitudes shape GI adoption decisions, though economic motivations remain dominant [33].

Furthermore, the influence of subjective norms on perceived behavioural control implies that social pressures can enhance producers’ confidence in their ability to complete the certification process, which is also supported by [43]. These findings challenge the conventional TPB model, which posits that social norms strongly affect behavioural intentions. Instead, the results suggest that subjective norms effectively shape attitudes but do not independently drive adoption behaviour. This implies that the social influence must be complemented by economic incentives or regulatory support to motivate actual certification adoption, highlighting the need for a comprehensive approach in promoting adoption.

A key finding was the strong and significant influence of attitudes on the willingness to adopt GI certification. This indicates that when individuals have a favourable attitude, they are much more likely to engage in it. Attitude is therefore a crucial factor driving willingness. This result is also consistent with the previous findings of [128], who also stated that attitudes toward integrated pest management (IPM) practices are an important component of farmers’ dealings, playing a vital role in their covert or overt behaviours in Iran. This study also supports the results of [61], who revealed that attitude is one of the main determinants that influenced farmers’ intention to plant trees in their coffee gardens in Africa. Moreover, refs [34,43] also stated that there is a significant impact of attitudes on the intention to adopt GI standards and practices. Therefore, it is important to note that this finding aligns with the core premise of the TPB, which asserts that individuals who hold favourable attitudes toward a particular behaviour are more likely to develop a firm intention to engage in it. In the context of this study, producers who perceive GI certification as valuable, beneficial, and aligned with their interests are more inclined to adopt the certification. This positive relationship between attitude and the willingness to adopt highlights the importance of fostering favourable perceptions of GI certification. Producers who recognise the value of GI certification, such as its potential to enhance product differentiation, secure premium pricing, and protect local heritage, are more likely to pursue certification. This finding reinforces the role of attitudinal factors in shaping behavioural intentions. It enlightens the readers about the key motivators for adoption, supporting the argument that targeted awareness campaigns emphasising the unique benefits of GI certification can positively shape producer attitudes.

While attitudes strongly influence the willingness to adopt GI certification, other psychological constructs such as subjective norms and perceived behavioural control do not have a significant effect on the willingness for GI certification. The results of our study contradict the results of [128], who stated that subjective norms as well as perceived behavioural control have a significant influence on intentions in the original model of the TPB. However, their results are also insignificant in the extended model of the TPB. The main reason for this can be attributed to the inclusion of additional constructs and the relationships between subjective norms, attitudes, and PBC in the integrative model of the TPB. The present study contradicts the findings of [34,61], who reported a significant relationship between subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and intentions or willingness. Thus, this study suggests that producers’ willingness to adopt GI certification is driven more by intrinsic beliefs and perceived benefits than by external social influences or the perceived ease of the certification process. Furthermore, this finding suggests that even if producers believe they possess the necessary skills and resources to obtain a GI certification, this confidence does not automatically translate into a willingness to adopt. The disconnect between perceived behavioural control and the willingness to adopt GI certification may be attributed to external challenges, such as bureaucratic complexities, high certification costs, and limited institutional support, which can undermine producers’ confidence. Producers may perceive the certification process as overly complicated, resource-intensive, or uncertain, making them hesitant to pursue certification despite believing in its benefits. The limited direct impact of ‘subjective norms’ and ‘perceived behavioural control’ on ‘willingness’ challenges the traditional assumptions of the TPB, which typically posits that social pressures and perceived control are key determinants of behavioural intentions.

6. Implications

The findings of this study provide critical insights for producers, policymakers, government bodies, industry stakeholders, and researchers aiming to promote the adoption of GI certification. This research has underscored the critical importance of developing targeted strategies that simultaneously advance economic development as well as safeguard cultural heritage. By identifying economic benefits and attitudes of producers as the primary drivers for the adoption of GI certifications, the findings suggest a multi-pronged approach. First, marketing efforts should strategically reposition GI-certified Cashew Feni as a premium, culturally symbolic product within the broader framework of Goa’s cultural tourism. The adoption of GI certifications extends far beyond the mere preservation of cultural heritage. It functions as a powerful strategic instrument for regional branding, enabling producers to craft distinct market identities that are rooted in tradition, authenticity, and geographic uniqueness. By differentiating products like Cashew Feni from mass-produced alternatives, the GI status enhances their perceived value in both domestic and international markets seeking authentic cultural experiences. This distinctiveness will help to elevate the competitive positioning of local goods and also foster consumer trust and loyalty, particularly among those concerned with quality and provenance.

Second, to enhance producer participation, it is essential to implement comprehensive financial support mechanisms. These may include direct subsidies for certification costs, targeted grant programmes, microfinance schemes tailored for small-scale distillers, and access to low-interest loans. Such financial instruments can mitigate the cost-related barriers that often prevent small and marginal producers from obtaining GI certifications, thereby encouraging a wider adoption across the industry. Together, these integrated measures can foster a more inclusive and sustainable local economy. By aligning financial incentives with cultural preservation, stakeholders can not only strengthen the market viability of Cashew Feni but also ensure the protection and continued transmission of Goa’s indigenous knowledge systems and artisanal traditions.

Third, building the capacity among producers is essential not only for sustaining the momentum of GI certification [129] but also for advancing broader objectives of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [130]. Therefore, regular training programmes on certification processes, branding, quality standards, and entrepreneurial skills can bridge knowledge gaps and merge traditional practices with modern business techniques. Strengthening producer associations as hubs for knowledge-sharing and innovation will further bolster the industry’s resilience. Consumer education campaigns should emphasise the authenticity, heritage value, and superior quality of GI-certified products. Integrating consumer feedback into product development and marketing strategies will ensure that offerings remain aligned with evolving market demands, strengthening brand loyalty and trust. Thus, this will support the livelihoods of local communities, particularly small-scale and artisanal producers, by generating premium pricing opportunities and a stable demand. In doing so, it will encourage environmentally and culturally sustainable production practices, help retain traditional knowledge systems, and strengthen local economies.

Fourth, and lastly, fostering a collaborative entrepreneurial ecosystem and pursuing global market opportunities are crucial for the long-term success of the Goan Feni industry. Forming producer clusters can enhance bargaining power and operational efficiency, while business incubators can drive innovation and scalability. Internationally, positioning GI-certified Cashew Feni as a unique export product, supported by strategic partnerships with trade organisations, can create access to premium markets and elevate Goa’s cultural identity on the global stage. Since Cashew Feni is typically produced by small-scale producers who are largely unorganised, Goa’s Conformity Assessment Board should develop policies to support and formalise the operations of informally operating producers. The board should also work towards simplifying procedures and making them easy to understand for individuals with a limited educational background. Ultimately, this comprehensive, four-pronged strategy lays the foundation for sustainable growth, cultural pride, and the global recognition of Goa’s iconic spirit through GI certification.

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Scope for Further Research

This research emphasises the importance of innovation as a driving force in enabling producers to overcome challenges, unlock new opportunities, and ensure long-term success in an increasingly competitive business environment. It demonstrates the pivotal role of innovation in encouraging Goa Cashew Feni producers to adopt GI practices. GI adoption serves as a strategic mechanism to establish distinct market identities, enhance competitive advantages, and promote long-term sustainable growth. In this regard, the producers can tap into the new markets by integrating traditional knowledge with modern business practices, building customer trust, and securing premium product pricing. The findings highlight the importance of financial incentives, such as subsidies or low-interest loans, to reduce the costs associated with GI certification. Producers’ attitudes towards GI adoption also play a critical role in encouraging them to see it as a pathway to innovation and growth. Therefore, collaborative efforts, such as forming producer groups or cooperatives, can further reduce operational challenges while fostering entrepreneurship and knowledge-sharing. Marketing innovation is another key factor, and therefore, the unique identity of GI-certified Cashew Feni can be leveraged through storytelling, cultural branding, and partnerships with tourism initiatives. Further, digital platforms and global trade networks offer opportunities to position Cashew Feni as a premium product internationally, expanding its market reach and appeal. By adopting GI practices and supporting innovative strategies, Cashew Feni producers can preserve their craft and transform their businesses into booming ventures that balance tradition and modernity.

This study also has limitations. First, the focus on a specific region and crop may limit the generalisability of the findings. While this approach allows for an in-depth analysis within a defined context, the conclusions drawn may not be applicable to other regions with different climatic, socio-economic, or agronomic conditions. Variations in soil quality, infrastructure, policy frameworks, and market access can significantly influence outcomes; thus, caution must be exercised when attempting to generalise the results beyond the studied setting. Future research could benefit from comparative analyses across multiple regions and crop types to enhance the robustness and external validity of the findings. Second, this study’s sample also comprised varied socio-demographic characteristics, which limits its generalisability to regions with different demographic features. These socio-demographic limitations may influence the perspectives captured in this study, thereby affecting the applicability of the findings to broader or more diverse populations. Future research should consider more inclusive sampling approaches that ensure a balanced representation of the demographics, which will enable a more comprehensive understanding of the research. Third, although this study includes GI-certified as well as non-GI-certified Cashew Feni producers, the representation of GI-certified Feni producers was negligible because the state had only one GI-certified producer at the time this study was conducted. Hence, this study’s results are mainly from the point of view of non-GI-certified producers, and therefore have a limited scope for generalisation. In addition, this study’s findings are based explicitly on perspectives from Cashew Feni producers and can therefore have limitations with regard to their applicability in the context of other GI-tagged products. Further research from the point of view of GI-certified producers can reveal additional insights into the theme of this study. Fourth and last, while the extended TPB serves as the primary framework in analysing Cashew Feni producers’ willingness to adopt GI tags in this study, the findings of this study have not been extendable to other GI-tagged products. Future researchers can use complementary models to generate deeper insights into behavioural intentions regarding GI certification adoption and develop further targeted policy and outreach strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S. and S.S.; methodology, R.F.; software, V.S., S.K. and R.F.; validation, R.F. and S.S.; formal analysis, V.S. and R.F.; investigation, V.S.; data curation, V.S., S.K. and R.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S.and R.F.; writing—review and editing, R.F., S.S.; S.K. and S.G.; visualisation, R.F.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Government College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Khandola, Marcela, Goa, India (Certificate Ref. No. GCASCK/RF/GI/CC-01 dated 8 January 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study will be made available by authors, on request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the guidance and support received from the staff of the institution where this study was conducted. We also express our gratitude to all individuals who supported this research by agreeing to be a part of the sample, which has been the basis of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GI | Geographical Indication |

| AT | Attitude |

| AW | Awareness |

| WTA | Willingness to Adopt Geographical Indication Tag |

| PBC | Perceived Behavioural Control |

| PEB | Perceived Economic Benefit |

| SN | Subjective Norm |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait |

| FLC | Fornell Larcker Criterion |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares–Structural Equation Modelling |

| PGI | Protected Geographical Indication |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behaviour |

| EU | European Union |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| CAB | Conformity Assessment Board |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variables used in the questionnaire.

Table A1.

Variables used in the questionnaire.

| Code | Variables |

|---|---|

| Awareness | |

| AW 1 | I am aware of the GI tag designation for Cashew Feni in Goa. |

| AW 2 | I am aware that Cashew Feni is the only alcoholic beverage in India that has a GI tag. |

| AW 3 | I am informed that the GI tag differentiates Cashew Feni from other alcoholic beverages. |

| AW 4 | I am aware of the historical and cultural reasons behind granting the GI tag to Feni. |

| AW 5 | I am familiar with the organisations responsible for controlling the production of GI-tagged Feni. |

| AW 6 | I am aware of the production and labelling standards required for GI-tagged Cashew Feni. |

| AW 7 | I am aware that the GI tag helps in protecting Cashew Feni from imitation products. |

| AW 8 | I am aware of the government or regulatory bodies involved in GI certification. |

| Attitude Toward GI Practices | |

| AT 1 | Following GI standards helps preserve the authenticity of Feni. |

| AT 2 | Adopting GI practices makes my product more competitive in the market. |

| AT 3 | GI standards improve the reputation of Cashew Feni producers in Goa. |

| AT 4 | Complying with GI practices enhances the authenticity and quality of production. |

| AT 5 | I believe that adhering to GI standards reduces the risk of market rejection. |

| AT 6 | GI certification helps differentiate my product from competitors. |

| Subjective Norms | |

| SN 1 | I know other Cashew Feni producers comply with GI standards. |

| SN 2 | Producer associations encourage me to consistently follow GI standards. |

| SN 3 | I am encouraged by my peers to comply with GI certification requirements. |

| SN 4 | Regulatory authorities actively promote and motivate me to adopt GI practice. |

| SN 5 | Customer preferences for GI-tagged Feni influence my decision to comply with GI standards. |

| SN 6 | My family supports my efforts to produce GI-certified Feni. |

| Perceived Behavioural Control | |

| PBC 1 | I can access the resources (equipment, raw materials) required to follow GI standards. |

| PBC 2 | Complying with GI standards does not disrupt my production schedule. |

| PBC 3 | I can quickly obtain information and guidance about GI practices. |

| PBC 4 | The costs of obtaining and maintaining GI certification are manageable. |

| PBC 5 | I have sufficient knowledge to meet the documentation requirements for GI certification. |

| PBC 6 | I can control the quality of my production process to meet GI standards. |

| PBC 7 | External factors, such as market demand, do not hinder my ability to follow GI practices. |

| Perceived Economic Benefits | |

| PEB 1 | GI-tagged Cashew Feni will earn a higher price than non-GI Cashew Feni in the market. |

| PEB 2 | Complying with GI standards opens access to premium markets. |

| PEB 3 | The GI tag can improve my financial stability as a Cashew Feni producer. |

| PEB 4 | GI-certified Cashew Feni can generate long-term economic benefits for producers. |

| PEB 5 | Buyers and retailers are more interested in purchasing GI-tagged Feni. |

| PEB 6 | GI certification reduces competition from counterfeit or low-quality Cashew Feni. |

| PEB 7 | I achieve better profit margins by producing GI-tagged Cashew Feni. |

| Willingness to Adopt the GI Tag | |

| WTA 1 | I am willing to register my Cashew Feni production under the GI framework. |

| WTA 2 | I plan to explore new markets where GI certification can be an advantage. |

| WTA 3 | I plan to invest in my facilities or equipment to comply with GI requirements. |

| WTA 4 | I will promote the benefits of GI-tagged Cashew Feni to other producers. |

| WTA 5 | I intend to educate my customers about the importance of GI certification. |

| WTA 6 | I will actively participate in associations or groups supporting GI-tagged Feni. |

| WTA 7 | I intend to adopt the GI certification to protect my product from imitation and counterfeiting. |

| WTA 8 | I believe that adopting the GI tag will provide long-term economic benefits. |

References

- Anseera, T.P.; Alex, J.P. Construction of a Knowledge Test to Measure the Level of Knowledge of Farmers on Geographical Indications in Agriculture. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2024, 42, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, R.; Singh, H.; Prashar, S. Branding of geographical indications in India: A paradigm to sustain its premium value. Int. J. Law Manag. 2014, 56, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A. Social Dynamics of Geographical Indications: Community Empowerment and Collective Identity. Int. J. All Res. Educ. Sci. Methods 2024, 12, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intellectual Property India. 2025. Available online: https://ipindia.gov.in/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Rangnekar, D. Remaking place: The social construction of a geographical indication for Feni. Environ. Plan. A 2011, 43, 2043–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, P. Culture and alcohol use in India. Off. J. World Assoc. Cult. Psychiatry 2015, 10, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Excise. Government of Goa|Official Portal. 2025. Available online: https://www.goa.gov.in/department/department-of-excise/ (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- John, I. Consumer Perceptions, Preferences and Awareness Towards Potential Geographical Indications of Products in Tanzania. Tanzanian Econ. Rev. 2023, 12, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.A.; Lourenzani, A.E.B.S.; Caldas, M.M.; Bernardo, C.H.C.; Bernardo, R. The benefits and barriers of geographical indications to producers: A review. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2022, 37, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S. Goa’s Cashew Nuts Get GI Tag. The Navhind Times, 4 October 2023. Available online: https://www.navhindtimes.in/2023/10/04/goanews/goas-cashew-nuts-get-gi-tag/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Patnaik, S. Govt Forms Certifying Body to Cash in on Feni’s GI Tag. The Navhind Times, 30 August 2024; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Prathap, S.K.; Sreelaksmi, C.C. Determinants of purchase intention of traditional handloom apparels with geographical indication among Indian consumers. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2022, 4, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, N. 50% Drop in Cashew Output This Year in Goa: Forest Devpt Corp. 2024. Available online: https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/goa/50-drop-in-cashew-output-this-year-in-goa-forest-devpt-corp/articleshow/110019505.cms (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Putri, R.W.; Putri, Y.M.; Pandjaitan, D.R.H. Challenges of Geographical Indication in Indonesia: A Study from Lampung Province; Atlantis Press SARL: Paris, France, 2023; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlina, B. Implementation of Legal Protections of Geographical Indications of Lampung Robusta Coffee in Improving the Economy of West Lampung Coffee Farmers. Pena Justisia: Media Komun. Dan Kaji. Huk. 2023, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubia, P. The Disappearance of Traditions: The Use of Geographical Indications and Collective Marks to Prevent Loss of Culture in South America. IIC Int. Rev. Intellect. Prop. Compet. Law. 2024, 55, 1257–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.L.; Silva, G.F.; Da Souza, A.L.G.; de Bisneto, J.P.M.; Silva, E.D.S. Geographical Indication. Int. J. Innov. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, A.; Modak, S.; Padhy, C. Willingness to Adopt the Recommended Practices of Organic Turmeric among Kandhamal Farmers of Odisha. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 39, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggoro, T.R.; Fadillah, S.N.; Prayoga, K. Farming performance and evaluation of the adoption of robusta coffee cultivation based on geographical indication in Candiroto District, Temanggung Regency. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1364, 012041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Nisa, K.; Halabi, M. Preservation of Traditional Miao Batik: Safeguarding Cultural Heritage in its Country of Origin. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2024, 14, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harianto, D.; Sitanggang, A.T.; Ritonga, N.S.; Sianipar, R.; Siahaan, P.G.; Angin, R.B.B.P. Protection Geographical Indication of Cimpa Tuang Food: Measuring Cultural and Economic Value in Sukalaju Village. Edumaspul J. Pendidik. 2023, 7, 3428–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirosha, R.; Mansingh, J.P. Geographical indication tag for agricultural produces: Challenges and methods. Multidiscip. Rev. 2024, 7, e2024206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnero, S.; Giordano, S. Sui Generis Geographical Indications Fostering Localised Sustainable Fashion: A Cross-Industry Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantyik, L.; Török, Á. Estimating the market share and price premium of GI foods- the case of the Hungarian food discounters. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; De Filippis, F.; Giua, M.; Vaquero-Piñeiro, C. Geographical Indications and local development: The strength of territorial embeddedness. Reg. Stud. 2021, 56, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, F.W.; Ackello-Ogutu, C.; Mburu, J.; Egelyng, H. Producers’ perception of geographical indications as a product diversification tool for agrifood products in semi-arid regions of Kenya. Int. J. Food Agric. Econ. 2018, 6, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maina, F.W.; Mburu, J.; Ackello-Ogutu, C.; Egelyng, H. Intellectual property and agricultural trade: Producer perceptions of tea and coffee as potential geographical indications. Open Agric. 2018, 3, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liang, Z.; Jin, H.; Chen, F. Geographical indication of agricultural products promotes the development of the local tourism economy. Front. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 4, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipkoech, B.; Isarie, V. Adoption of Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) for Kenyan Tea. Int. J. Engl. Lit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 7, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingole, A.D.; Kumar, A.; Jadhav, P.J.; Kulkarni, S.H. Geographical Indication of Fruit Crops in India and Its Protection Abroad. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2023, 13, 1026–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafrańska, J.O.; Stasiak, D.M.; Sołowiej, B.G. Promotion of Cultural Heritage—Regional and Traditional Polish Meat Products. Theory Pract. Meat Process. 2021, 6, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, N.; Çobanoğlu, F.; Tunalıoğlu, R. The Link Between Geographic Indication, Sustainability, and Multifunctionality: The Case of Table Olive Groves in Western Turkey. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2023, 65, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ihsaniyati, H.; Setyowati, N.P. Factors Motivating the Adoption of Geographical Indication-Based Quality Standards Among Robusta Coffee Farmers in Indonesia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2022, 23, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, A.; Crescimanno, M.; Abbruzzo, A.; Chironi, S.; Tinervia, S. The premium price for Italian red wines in new world wine consuming countries: The case of the Russian market. J. Wine Res. 2017, 28, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacarne, A.; Nunes-Silva, L.; De-Bortoli, R. Geographical Indication as a Tool for Regional Development: An Opportunity for Small Farmers to Excel in the Market. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 9, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, I.; Lokina, R.; Egelyng, H. Small-scale producers of quality products with the potential of geographical indication protection in Tanzania. Int. J. Food Agric. Econ. 2020, 8, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curzi, D.; Huysmans, M. The Impact of Protecting EU Geographical Indications in Trade Agreements. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2022, 104, 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Anh, D.T.; Moustier, P. The benefits of geographical indication certification through farmer organizations on low-income farmers: The case of Hoa Vang sticky rice in Vietnam. Cah. Agric. 2021, 30, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joao, A.R.B.; Luzardo, F.; Vanderson, T.X. An interdisciplinary framework to study farmers’ decisions on adoption of innovation: Insights from Expected Utility Theory and Theory of Planned Behaviour. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2015, 10, 2814–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicen, P.; Shelby, D. Hunt’s legacy, the R-A theory of competition, and its perspective on the geographical indications (GIs) debate. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2021, 31, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksono, P.; Irham Mulyo, J.H.; Suryantini, A.; Permadi, D.B. Small-Scale Farmers’ Preference in Adopting the Geographical Indications’ Code of Practice to Produce Coffee in Indonesia: A Choice Experiment Study. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 316, 02018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksono, P.; Irham Mulyo, J.H.; Suryantini, A. Farmers’ willingness to adopt geographical indication practice in Indonesia: A psycho behavioral analysis. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laksono, P.; Arina, A.D.; Hanapi, S. Smallholder Farmer’s Perception on Coffee Production under Geographical Indication Scheme. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 444, 02022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsaniyati, H.; Setyowati, N.P. Strategy of Improving the Farmers’ Adoption of Temanggung Robusta Coffee’s Geographical Indication Standard. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 519, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsaniyati, H.; Setyowati, N.; Phitara Sanjaya, A. Farmers’ attitude to standard production methods based on Temanggung robusta coffee’s geographical indication. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 518, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecandelaere, E.; Teyssier, C.; Barjolle, D.; Fournier, S.; Beucherie, O.; Jeanneaux, P. Strengthening Sustainable Food Systems through Geographical Indications: Evidence from 9 Worldwide Case Studies. J. Sustain. Res. 2020, 2, e200032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetschki, K.; Peerlings, J.; Dries, L. The impact of geographical indications on farm incomes in the EU olives and wine sector. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menggala, S.R.; Vanhove, W.; Muhammad, D.R.A.; Rahman, A.; Speelman, S.; van Damme, P. The effect of geographical indications (GIs) on the koerintji cinnamon sales price and information of origin. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhika, A.M.; Thomas, K.J.; Kuruvila, A.; Raju, R.K. Assessing the Impact of Geographical Indications on Well-Being of Rice Farmers in Kerala. Int. J. Intellect. Prop. Rights 2018, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, N. Economic impact of local geographical indication products on farmers: A case of Kelkit sugar (dry) beans. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2325083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, B.; Gokovali, U. Geographical Indications: The Aspects of Rural Development and Marketing Through the Traditional Products. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 62, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilavanichakul, A. The Economic Impact of Arabica Coffee Farmers’ Participation in Geographical Indication in Northern Highland of Thailand. J. Rural Probl. 2020, 56, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshwaran, M.; Rani, A.J.; Sabarinathan, C. Awareness Level of Geographical Indication (GI) on Madurai Malli. Asian J. Agric. Ext. Econ. Sociol. 2022, 40, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solanki, D.; Tiwari, V. Enhancing Awareness Among Ujjain Batik Prints’ Artisans About the Geographical Indication Tag. ShodhKosh. J. Vis. Perform. Arts 2024, 5, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, D.T.; Selvarani, G.; Senthilnathan, S.; Prabakaran, K. Awareness Level of Geographical Indication on Kanyakumari Matti Banana. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2024, 46, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Manchikanti, P.; Bhattacharya, N.S. Comparative Perspectives on the Protection of Food Geographical Indications in Asian Countries. Asian J. Comp. Law 2024, 19, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesić, Ž.; Božić, M.; Cerjak, M. The impact of geographical indications on the competitiveness of traditional agri-food products. J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 2017, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonigala, D.; Olekar, J.; Patil, Y.S.; Naresh, A. Comparative Economic Analysis of GI Tagged Chilli and Hybrid Teja Chilli in the Guntur District of Andhra Pradesh, India. J. Sci. Res. Rep. 2024, 30, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A. Protection of geographical indication products from different states of India. J. Intellect. Prop. Rights 2020, 25, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]