Cross-Cultural Competence in Tourism and Hospitality: A Case Study of Quintana Roo, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Intercultural Empathy

1.1.2. Cultural Intelligence

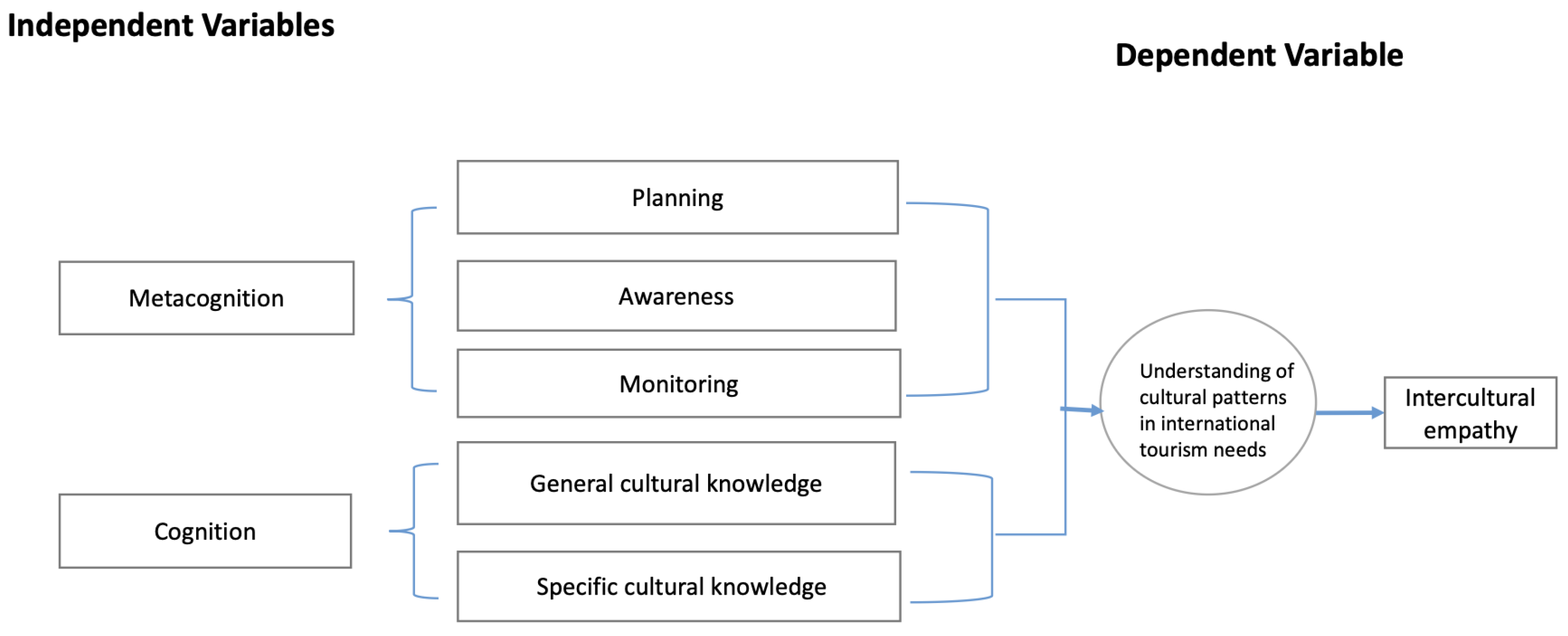

1.1.3. Metacognitive and Cognitive Cultural Intelligence

1.1.4. Intercultural Empathy, Metacognitive Intelligence, and Cognitive Intelligence in the Context of Tourism

2. Methodology

2.1. Variables

2.1.1. Population

2.1.2. Sample Size

2.1.3. Statistical Analysis

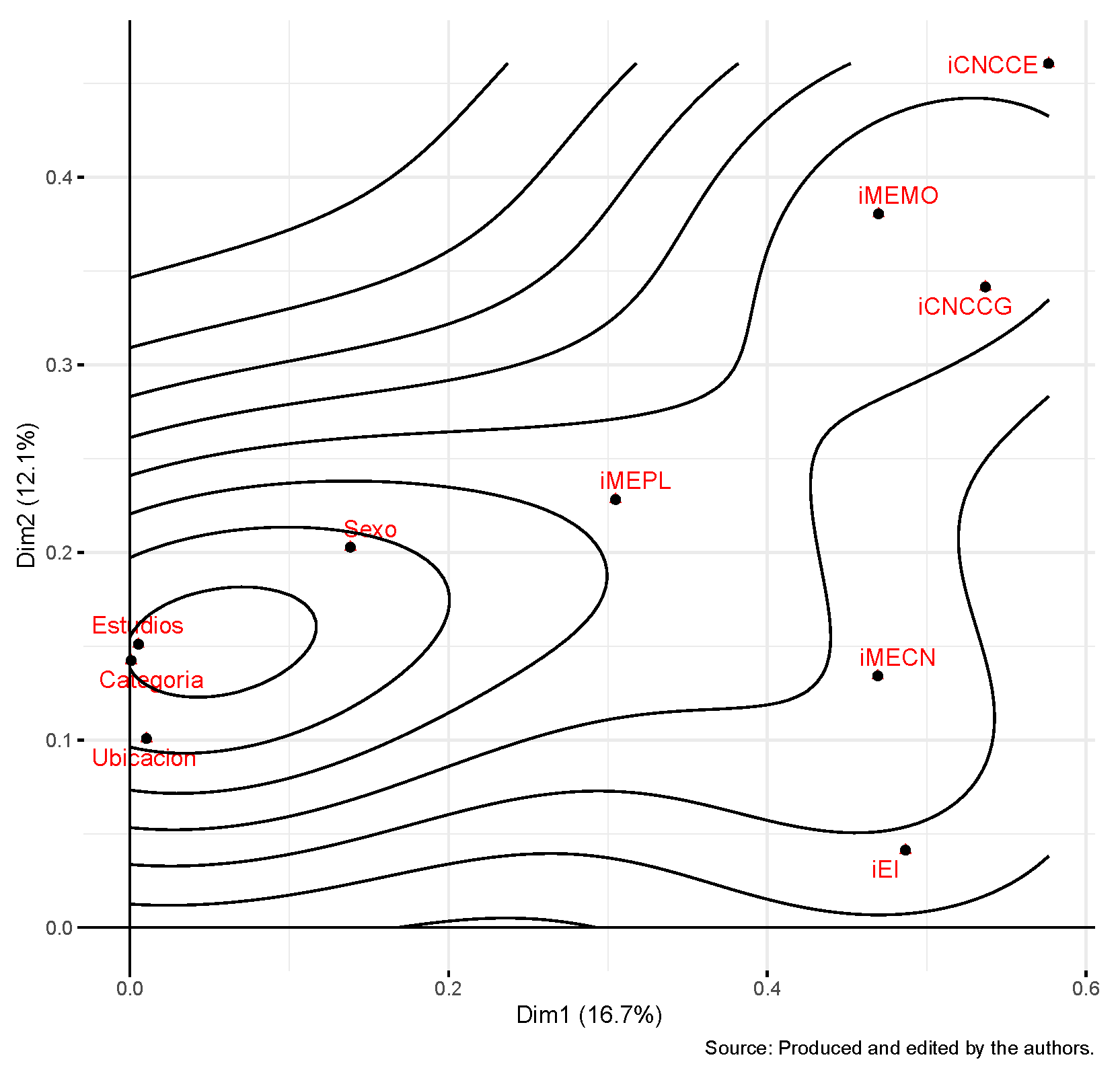

2.1.4. Basics of Multiple Correspondence Analysis

2.1.5. Software

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Multiple Correspondence Analysis

3.3. Ordinal Logistic Regression Analysis

3.3.1. Specific Cultural Knowledge

- CNCCE1: Assesses the capacity to discern how culture manifests in a particular community.

- CNCCE2: Assesses the extent of interest in understanding the value system of a specific cultural group.

- CNCCE3: Assesses the extent of interest in furthering understanding of a specific culture.

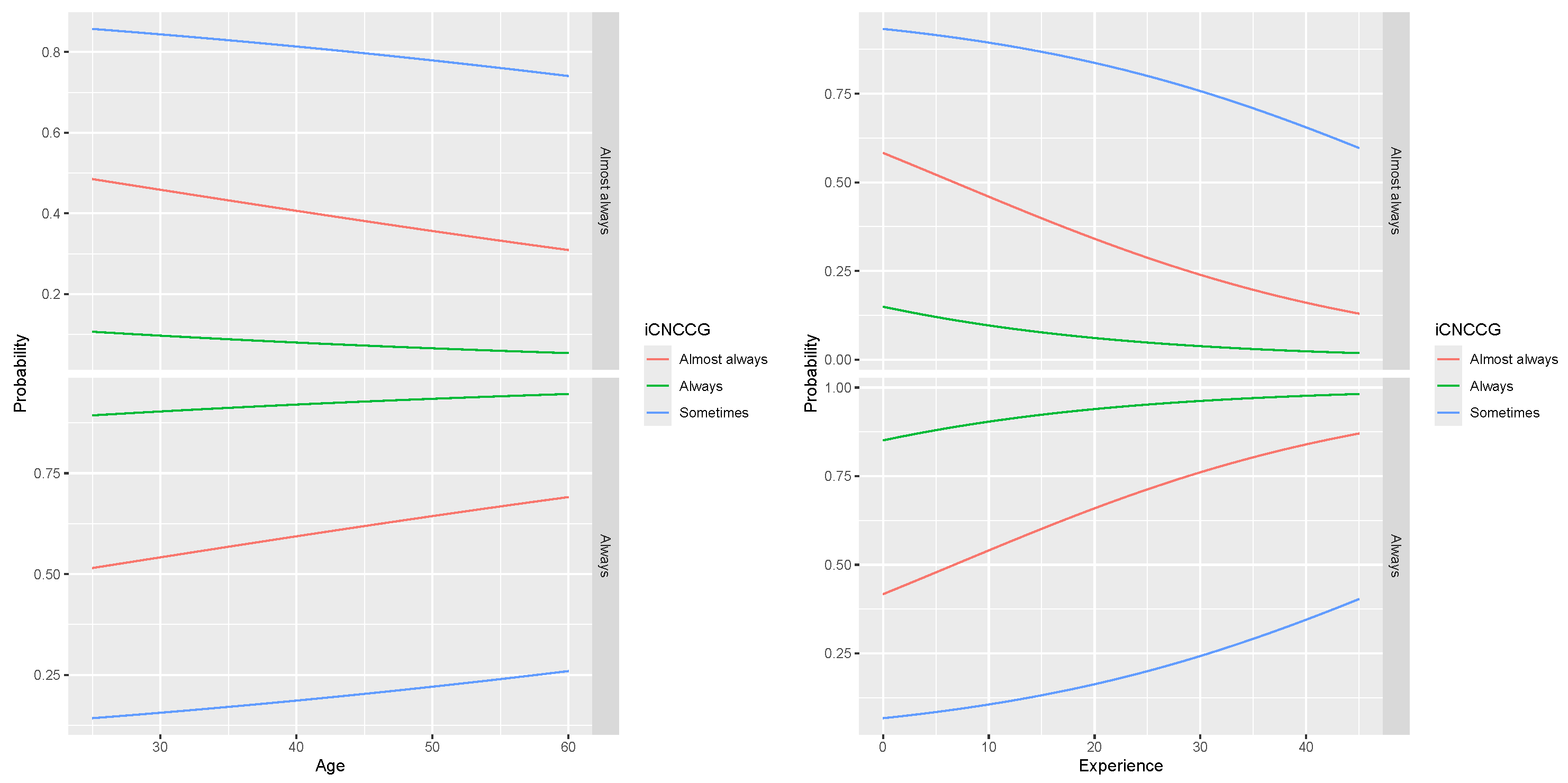

3.3.2. General Cultural Knowledge

- CNCCG1: Assesses the ability to distinguish between the various cultural patterns that elucidate the behaviours of cultures.

- CNCCG2: Assesses awareness of the impact of cultural factors on individual behaviour.

- CNCCG3: Assesses familiarity with diverse cultural norms and practices that enable an individual to navigate interactions with other cultures in a manner that avoids misunderstandings.

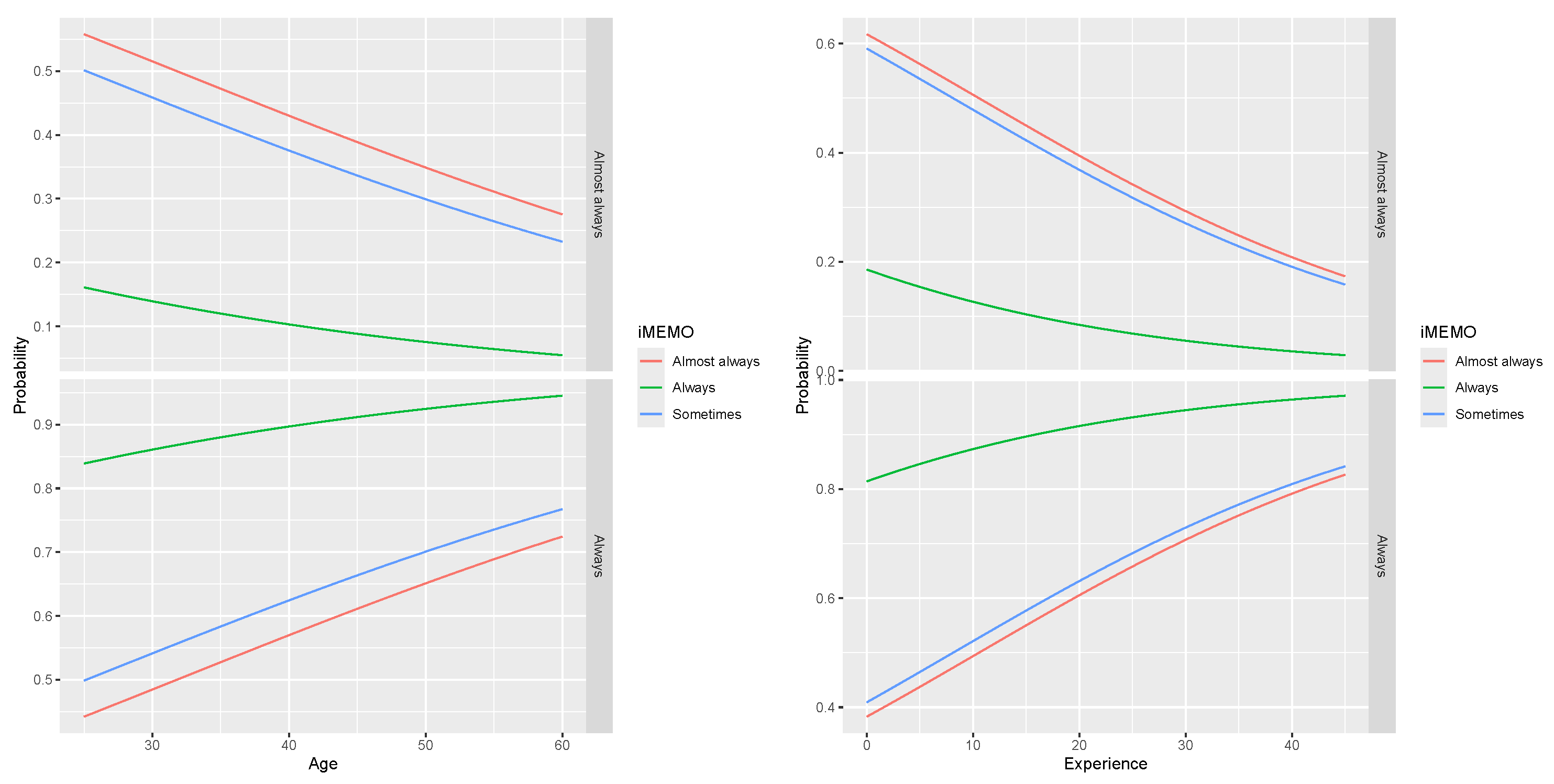

3.3.3. Monitoring

- MEMO 1: Assesses the ability to understand that culture comprehension is contingent upon interactions with individuals from that culture.

- MEMO 2: Assesses the ability of an individual to modify their communication style to align with the cultural norms of the group with whom they am interacting.

- MEMO 3: Assesses the accuracy of an individual’s cultural understanding when interacting in diverse cultural contexts.

3.3.4. Awareness

- MECN1: Assesses awareness of how one’s culture influences interactions with people from other cultures.

- MECN2: Assesses awareness of the importance of learning about other cultures.

- MECN3: Assesses awareness of the importance of culture to the individual.

- MECN4: Assesses the ability to distinguish between one’s own cultural attitudes and those of others.

3.4. Linking the Findings to the Relevant Theoretical Framework

3.5. Practical Interpretation of Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IE | Intercultural empathy |

| CQ | Cultural intelligence quotient |

| ME | Metacognitive cultural intelligence |

| MEPL | Metacognitive cultural intelligence, planning |

| MECN | Metacognitive cultural intelligence, awareness |

| MEMO | Metacognitive cultural intelligence, monitoring |

| CN | Cognitive cultural intelligence |

| CNCCG | Cognitive cultural intelligence, general cultural knowledge |

| CNCCE | Cognitive cultural intelligence, specific cultural knowledge |

| MCA | Multiple correspondence analysis |

| OLR | Ordinal logistic regression |

References

- Gabel-Shemueli, R.; Westman, M.; Chen, S.; Bahamonde, D. Does cultural intelligence increase work engagement? The role of idiocentrism-allocentrism and organizational culture in MNCs. Cross Cult. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 26, 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.; Van Dyne, L.; Koh, C.; Ng, K.Y.; Templer, K.J.; Tay, C.; Chandrasekar, N.A. Cultural Intelligence: Its Measurement and Effects on Cultural Judgment and Decision Making, Cultural Adaptation and Task Performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2007, 3, 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, I.; Ehrnrooth, M.; Mäkelä, K.; Smale, A.; Sumelius, J. Talent management in multinational corporations. In The Oxford Handbook of Talent Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 461–477. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis, H.C. Cultural Intelligence in Organizations. Group Organ. Manag. 2006, 31, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Carballal, A.; Rey, U.; Carlos, J. Competencias profesionales y organizaciones multiculturales: Identificación e instrumentos de medida de la competencia intercultural. Rev. Int. Organ. 2020, 24, 367–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C. ‘Ripping Off’ Tourists: An Empirical Evaluation of Tourists’ Perceptions and Service Worker (Mis)Behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1070–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting-Toomey, S.; Yee-Jung, K.K.; Shapiro, R.B.; Garcia, W.; Wright, T.J.; Oetzel, J.G. Ethnic/cultural identity salience and conflict styles in four US ethnic groups. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2000, 24, 47–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agreda Sigindioy, T.M. Transformando la educación: El papel de la formación intercultural del profesorado para la integración de estudiantes migrantes internacionales. Innovaciones Educ. 2024, 26, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; De Galdeano García, P. Empatía en niños de 10 a 12 años. Psicothema 2006, 18, 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D.P. Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.M.; Starosta, W.J. The development and validation of the intercultural sensitivity scale. Hum. Commun. 2000, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Arjona Granados, M.d.P. La incidencia de empatía intercultural en hombres y mujeres que laboran en agencias de viajes en Nuevo León. Tur. Soc. 2022, 30, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyche, L.; Zayas, L.H. Cross-cultural empathy and training the contemporary psychotherapist. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2001, 29, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoal, C.; Eklund, J.; Hansen, E.M. Toward a conceptualization of ethnocultural empathy. J. Soc. Evol. Cult. Psychol. 2011, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidan, M.; Teagarden, M.; Bowen, D. Making it overseas. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, C.R.; Lingle, D.W. Cultural empathy in multicultural counseling: A multidimensional process model. In Counseling Across Cultures; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Asencio, C.E. Competências Interculturais: Impacto da oficina Comunicando-nos na sensibilidade intercultural de profesores universitários. Rev. Electrón. Educ. 2020, 24, 370–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.; Van Dyne, L.; Koh, C.; Ng, K. The measurement of cultural intelligence. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Meetings Symposium on Cultural Intelligence in the 21st Century, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–24 August 2004; Volume 214. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, S.; Van Dyne, L.; Rockstuhl, T.; Gelfand, M.; Chiu, C.; Hong, Y. Cultural intelligence. In Handbook of Advances in Culture and Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 5, pp. 273–324. [Google Scholar]

- Ratasuk, A.; Charoensukmongkol, P. Does cultural intelligence promote cross-cultural teams’ knowledge sharing and innovation in the restaurant business? Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2020, 12, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mobley, W.H.; Kelly, A. Linking personality to cultural intelligence: An interactive effect of openness and agreeableness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016, 89, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, D.L.; Michailova, S. Cultural Intelligence: A Review and New Research Avenues. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, M.A.; Budhwar, P. Cultural intelligence as a predictor of expatriate adjustment and performance in Malaysia. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, S.; Sharma, S. Examining the impact of personality traits on cultural intelligence. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 2017, 10, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Presbitero, A. Cultural intelligence (CQ) in virtual, cross-cultural interactions: Generalizability of measure and links to personality dimensions and task performance. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2016, 50, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, C.P. Redefining interactions across cultures and organizations: Moving forward with cultural intelligence. Res. Organ. Behav. 2002, 24, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.; Van Dyne, L. Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications; M.E. Sharpe Inc.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rockstuhl, T.; Dyne, L.V. A bi-factor theory of the four-factor model of cultural intelligence: Meta-analysis and theoretical extensions. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 2018, 148, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.; Worthley, R.; Macnab, B. Cultural Intelligence. Group Organ. Manag. 2006, 31, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P.C.; Ang, S. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures; Stanford Business Books: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L.; Ang, S.; Ng, K.Y.; Rockstuhl, T.; Tan, M.L.; Koh, C. Sub-Dimensions of the Four Factor Model of Cultural Intelligence: Expanding the Conceptualization and Measurement of Cultural Intelligence. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2012, 6, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuleja, E.A. Developing Cultural Intelligence for Global Leadership Through Mindfulness. J. Teach. Int. Bus. 2014, 25, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, A.; Inkpen, A.C. Cultural Intelligence and Offshore Outsourcing Success: A Framework of Firm-Level Intercultural Capability*. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Martínez, A.B. Empathy for social justice: The case of Malala Yousafzai. J. Engl. Stud. 2019, 17, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P.C.; Mosakowski, E. Cultural intelligence. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2004, 82, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Klafehn, J.; Banerjee, P.M.; Chiu, C.Y. Navigating Cultures: The Role of Metacognitive Cultural Intelligence. In Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications; M.E. Sharpe Inc.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 318–331. [Google Scholar]

- Korez-Vide, R.; Tanšek, V.; Milfelner, B. Assessing Intercultural Competence of Front Office Employees: The Case of Hotels in Slovenia; Tourism & Hospitality Industry: 2016; Indonesia and Vladimir State University: Jakarta, Indonesia; Vladimir, Russia, 2016; pp. 158–173. [Google Scholar]

- Coves-Martínez, Á.L.; Sabiote-Ortiz, C.M.; Frías-Jamilena, D.M. Cultural intelligence as an antecedent of satisfaction with the travel app and with the tourism experience. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Rohmetra, N. Cultural intelligence: Leveraging differences to bridge the gap in the international hospitality industry. Int. Rev. Bus. Res. Pap. 2010, 6, 216–234. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, P.; Rohmetra, N. Cultural intelligence and customer satisfaction: A quantitative analysis of international hotels in India. Rev. Manag. Ing. Econ. 2012, 11, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, R.; Cheung, C.; Lugosi, P. The impacts of cultural intelligence and emotional labor on the job satisfaction of luxury hotel employees. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, L.; Vargas-Sánchez, A.; Presenza, A.; Abbate, T. The Use of Intelligence in Tourism Destination Management: An Emerging Role for DMOs. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, H.; Hoojaghan, F.A.; Jenab, K.; Khoury, S. The effect of managers’ business intelligence on attracting foreign tourists case study. Int. J. Organ. Collect. Intell. (IJOCI) 2016, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.A.; Haffejee, B.; Corsun, D.L. The relationship between ethnocentrism and cultural intelligence. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2017, 58, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaibani, E.; Bakir, A. A reading in cross-cultural service encounter: Exploring the relationship between cultural intelligence, employee performance and service quality. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 17, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelin, I. Investigation on the Traditional Weaving Skills and Cultural Asset of Puniri of the Seediq; Cultural Asset Bureau, The Ministry of Culture: Taichung, Taiwan, 2014.

- Fakhreldin, H. The Effect of Cultural Intelligence on Employee Performance in International Hospitality Industries: A Case from the Hotel Sector in Egypt. Bus. Adm. 2011, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Navas Cueva, A.M.; Xue, J.; Kuypers, T.; Van Hoof, H.; Panchi-Enríquez, D.E.; Caiza, R. Inteligencia cultural en el lugar de trabajo: Un estudio entre empleados ecuatorianos de primera línea. COMPENDIUM Cuad. Econ. Adm. 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona Granados, M.d.P. Factores de la Inteligencia Cultural que Promueven la Empatía Intercultural de los Proveedores de Servicios con el Turismo Internacional en Quintana Roo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, San Nicolas de los Garza, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arjona Granados, M.d.P. Relevancia de la inteligencia cultural en la calidad en el servicio al turismo internacional. Rev. Col. San Luis 2024, 14, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, P. Contribution of mindfulness to customer orientation and adaptive selling. Int. J. Serv. Econ. Manag. 2019, 10, 335–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratasuk, A. The role of cultural intelligence in the trust and turnover of frontline hotel employees in Thailand. Humanit. Arts Soc. Sci. Stud. 2022, 7, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwani, S.; Jauhari, V. An exploratory study of competencies required to co-create memorable customer experiences in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 25, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona Granados, M.d.P.; Sevilla-Morales, J.A.; Galván-Vera, A.; Legarreta-González, M.A. An Examination of the Elements of Cultural Competence and Their Impact on Tourism Services: Case Study in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieseke, J.; Geigenmüller, A.; Kraus, F. On the Role of Empathy in Customer-Employee Interactions. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.; Hemsworth, K. Soft skills as key competencies in hospitality higher education: Matching demand and supply. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2011, 7, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe, J. Critical Tourism: Rules and Resistance. In The Critical Turn in Tourism Studies: Innovative Research Methods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, H. Empathy and tourism: Limits and possibilities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 57, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, P.R. Cultural Perspectives on International Negotiations. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Ang, S.; Tan, M.L. Intercultural Competence. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 489–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.Y.; Dyne, L.V.; Ang, S. From Experience to Experiential Learning: Cultural Intelligence as a Learning Capability for Global Leader Development. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2017, 8, 511–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.C.; Inkson, K. People Skills for Global Business: Cultural Intelligence; Berrett-Koenler: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Earley, P.C.; Ang, S.; Tan, J.S. CQ: Developing Cultural Intelligence at Work; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.C. Domain and Development of Cultural Intelligence. Group Organ. Manag. 2006, 31, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, E.D.; Peters, H.Y.S. Short-term cross-cultural study tours: Impact on cultural intelligence. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.; Van Dyne, L.; Ang, S. Cultural intelligence: Why every leader needs it. Intercult. Manag. Q. 2012, 13, 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur JR., W.; Bennet JR., W. The International Assignee: The relative importance of factors perveives to contribute to success. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Gobernación. Turistas extranjeros por país de Residencia y Aeropuerto a mayo de 2025. Available online: https://datatur.sectur.gob.mx/SitePages/Visitantes%20por%20Residencia.aspx (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Van Oudenhoven, J.P.; Van der Zee, K.I. Predicting multicultural effectiveness of international students: The Multicultural Personality Questionnaire. Int. J. Intercult. Relations 2002, 26, 679–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, K.I.V.D.; Brinkmann, U. Construct Validity Evidence for the Intercultural Readiness Check against the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2004, 12, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, D. Likert Scales…are the meaning of life. Topic report, 2008. Available online: https://cspages.ucalgary.ca/~saul/wiki/uploads/CPSC681/topic-dane-likert.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Sobalbarro-Figueroa, M.F.; Legarreta-González, M.A.; García-Fernández, F.; Olivas-García, J.M.; Carrillo-Soltero, M.E.; Guzmán-Rodríguez, A. Análisis Socioeconómico de los Pequeños Productores de Cacao en Honduras. Caso APROSACAO. Ceiba 2020, 0848, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-López, C.Y.; Esparza-Castruita, L.U.; Legarreta-González, M.A.; Olivas-García, J.M.; Uranga-Valencia, L.P.; Lujan-Álvarez, C. Impacto del cambio climático en la agricultura del Distrito de Riego 005 Chihuahua, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 2022, 13, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Morales, J.A.; Fernández-García, F.; Legarreta-González, M.A. Determinantes del emprendimiento en estudiantes universitarios en Tamaulipas, México. NovaRua 2022, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.A.; de Jesús Brambila-Paz, J.; García-Sánchez, R.C.; Omaña-Silvestre, J.M.; González-Estrada, A.; Legarreta-González, M.A. Factores socioeconómicos que afectan el rendimiento del cacao, en el norte centro, Nicaragua. Estud. Soc. Rev. Aliment. Contemp. Desarro. Reg. 2024, 34, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and visualize the results of multivariate data analyses. CRAN: Contributed Packages. 2016. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/factoextra/factoextra.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R Package, version 0.8-90; Foreign: Read Data Stored by ‘Minitab’, ‘S’, ‘SAS’, ‘SPSS’, ‘Stata’, ‘Systat’, ‘Weka’, ‘dBase’,…; 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/foreign/foreign.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Sievert, C. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H. R Package, version 1.4.0; kableExtra: Construct Complex Table with ‘kable’ and Pipe Syntax; 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/kableExtra/kableExtra.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Ooms, J. R Package, version 2.8.6; magick: Advanced Graphics and Image-Processing in R; 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/magick/vignettes/intro.html (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Josse, J.; Husson, F. missMDA: A Package for Handling Missing Values in Multivariate Data Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 70, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-387-95457-0. [Google Scholar]

- Daróczi, G.; Tsegelskyi, R. R Package, version 0.6.6; Pander: An R ‘Pandoc’ Writer; 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pander/pander.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Aust, F.; Barth, M. R Package, version 0.1.3; Papaja: Prepare reproducible APA journal articles with R Markdown; 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/papaja/index.html (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Bryan, J. R Package, version 1.4.5; Readxl: Read Excel Files; 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/readxl/readxl.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Wickham, H. Reshaping Data with the reshape Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2007, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M. R Package, version 0.2.5; Tinylabels: Lightweight variable labels; 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tinylabels/tinylabels.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Yee, T.W. The VGAM Package for Categorical Data Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 32, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparoidamis, N.G.; Tran, H.T.T.; Leonidou, C.N. Building Customer Loyalty in Intercultural Service Encounters: The Role of Service Employees’ Cultural Intelligence. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, S.K.; Brett, J.M. Fusing Creativity: Cultural Metacognition and Teamwork in Multicultural Teams. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2012, 5, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P. Marketplace Metacognition and Social Intelligence. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 28, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, T.; Ely, K. A Meta-Analysis of Self-Regulated Learning in Work-Related Training and Educational Attainment: What We Know and Where We Need to Go. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, S.; Morris, M.W.; Joh, J. Identifying and Training Adaptive Cross-Cultural Management Skills: The Crucial Role of Cultural Metacognition. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2013, 12, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.O.; de la O, I.L.R.; González, C.V. Tendencias del turismo hasta 2030. Contrastes entre lo internacional y lo nacional. In Anudar Red. Temas Pendientes y Nuevas Oportunidades de Cooperación en Turismo; lo Andreu, M.G.N., Barnet, A.F., Eds.; Publicacions Universitat Rovira i Virgili: Cd. de Mexico, Mexico, 2017; pp. 102–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Noriega, P. The Need For Leadership Support in Cross-Cultural Diversity Management in Hospitality Curriculums. Consort. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, P.F.; Avery, D.R.; Liao, H.; Morris, M.A. Does Diversity Climate Lead to Customer Satisfaction? It Depends on the Service Climate and Business Unit Demography. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 788–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietzschel, E.F.; Nijstad, B.A.; Stroebe, W. Relative accessibility of domain knowledge and creativity: The effects of knowledge activation on the quantity and originality of generated ideas. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Pearson, C.; Entrekin, L. Chinese cultural values and the Asian Meltdown. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2002, 29, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearns, N.; Devine, F.; Baum, T. The implications of contemporary cultural diversity for the hospitality curriculum. Educ. Train. 2007, 49, 350–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subdimension | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Planning (MEPL). The ability to organize the acquisition and management of cultural information in a structured manner. | - I plan before trying to interact with people from other cultures. |

| - I consider it necessary to foresee different cultural situations. | |

| - I endeavour to cultivate the requisite skills to engage in cross-cultural interactions in an appropriate manner. | |

| Awareness (MECN). The capacity to perceive and differentiate between one’s own and another’s cultural attitudes in a given situation. | - I am aware of the impact of my cultural background on my interactions with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds. |

| - I am aware of the importance of knowledge about other cultures. | |

| - I am aware of the importance of culture for a person. | |

| - I am able to differentiate between my own and other people’s cultural attitudes. | |

| Monitoring (MEMO). The capacity to modify planned actions and reorient them according to contextual demands. | - I understand a culture by interacting with people from that culture. |

| - I tailor my communication style to align with the cultural norms of the group with whom I am interacting. | |

| - I am aware of the veracity of my cultural knowledge when interacting with different cultures. |

| Subdimension | Indicators |

|---|---|

| General cultural knowledge (CNCCG). The understanding of the universal elements present in cultural development. | - I can describe the different cultural patterns that explain the behaviours of cultures. |

| - I have knowledge about the influence of culture on people. | |

| - My knowledge of cultures enables me to avoid misunderstandings in interactions with other cultures. | |

| Cultural knowledge (CNCCE). The understanding of the specific manner in which universal culture is expressed within a given community. | - I am aware of the ways in which culture manifests itself within a specific community. |

| - I am interested in understanding the value system of a certain cultural group. | |

| - When necessary, I am interested in deepening my knowledge of a certain culture. |

| Dependent Variable | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Cross-cultural empathy (also known as intercultural empathy) is the capacity to comprehend the emotions, thoughts, and behaviours of individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds. | - I am attentive to the emotional experiences of individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds. |

| - I consider myself sensitive to subtle cultural aspects when interacting with people from other cultures. | |

| - I detect when people are irritated. | |

| - I get to know others deeply. | |

| - I enjoy listening to the stories of people from other cultures. | |

| - I detect when people are in trouble. | |

| - I sympathize with people from other cultures. | |

| - I believe I have the ability to accurately understand the feelings of people from other cultures. | |

| - I respect the values and ways of behaving of people from other cultures. | |

| - I consider myself open-minded to people from other cultures. | |

| - I am cordial with people from other cultures. |

| Age | Experience | |

|---|---|---|

| Specific cultural knowledge | ||

| Always | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| Almost always | 0.63 | 0.66 |

| Sometimes | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| General cultural knowledge. | ||

| Always | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Almost always | 0.60 | 0.64 |

| Sometimes | 0.20 | 0.20 |

| Monitoring | ||

| Always | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Almost always | 0.58 | 0.60 |

| Sometimes | 0.63 | 0.63 |

| Awareness | ||

| Always | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| Almost always | 0.46 | 0.38 |

| Sometimes | 0.00 | 0.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arjona-Granados, M.d.P.; Galván-Vera, A.; Sevilla-Morales, J.Á.; Legarreta-González, M.A. Cross-Cultural Competence in Tourism and Hospitality: A Case Study of Quintana Roo, Mexico. World 2025, 6, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030108

Arjona-Granados MdP, Galván-Vera A, Sevilla-Morales JÁ, Legarreta-González MA. Cross-Cultural Competence in Tourism and Hospitality: A Case Study of Quintana Roo, Mexico. World. 2025; 6(3):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030108

Chicago/Turabian StyleArjona-Granados, María del Pilar, Antonio Galván-Vera, José Ángel Sevilla-Morales, and Martín Alfredo Legarreta-González. 2025. "Cross-Cultural Competence in Tourism and Hospitality: A Case Study of Quintana Roo, Mexico" World 6, no. 3: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030108

APA StyleArjona-Granados, M. d. P., Galván-Vera, A., Sevilla-Morales, J. Á., & Legarreta-González, M. A. (2025). Cross-Cultural Competence in Tourism and Hospitality: A Case Study of Quintana Roo, Mexico. World, 6(3), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6030108