The Public Health Impact of Foreign Aid Withdrawal by the United States Government and Its Implications for ARVs, Preexposure, and Postexposure Prophylaxis Medications in South Africa and Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

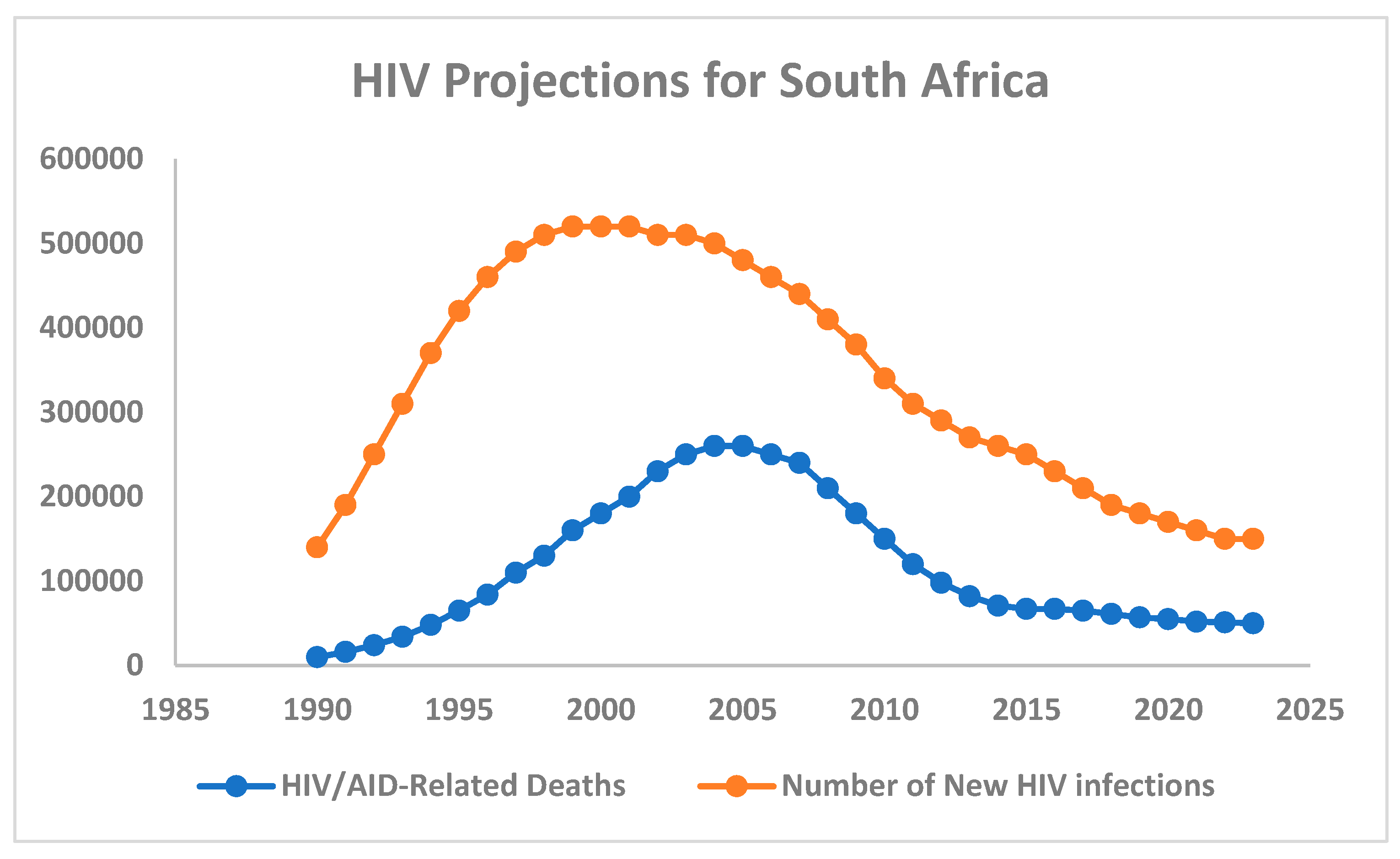

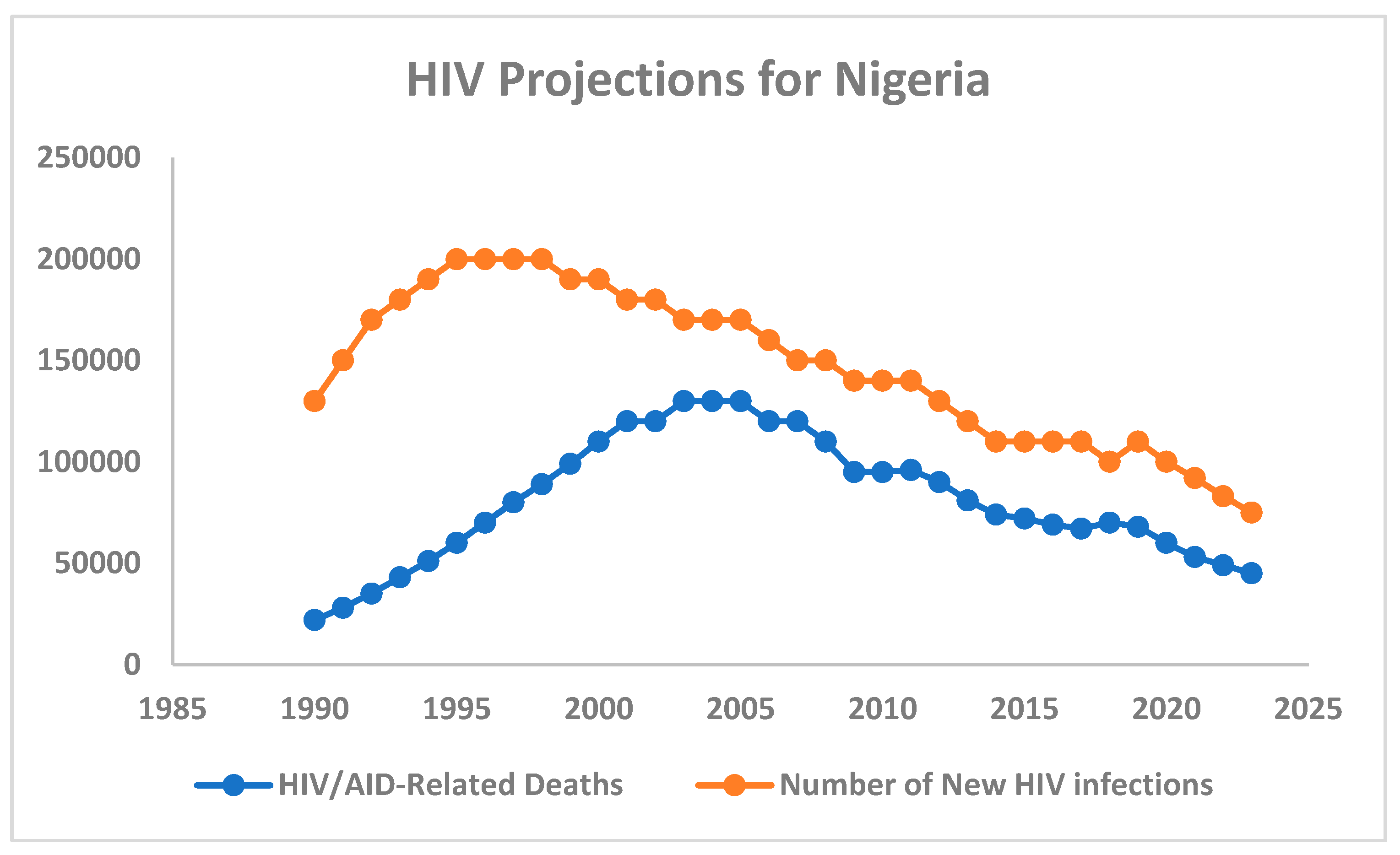

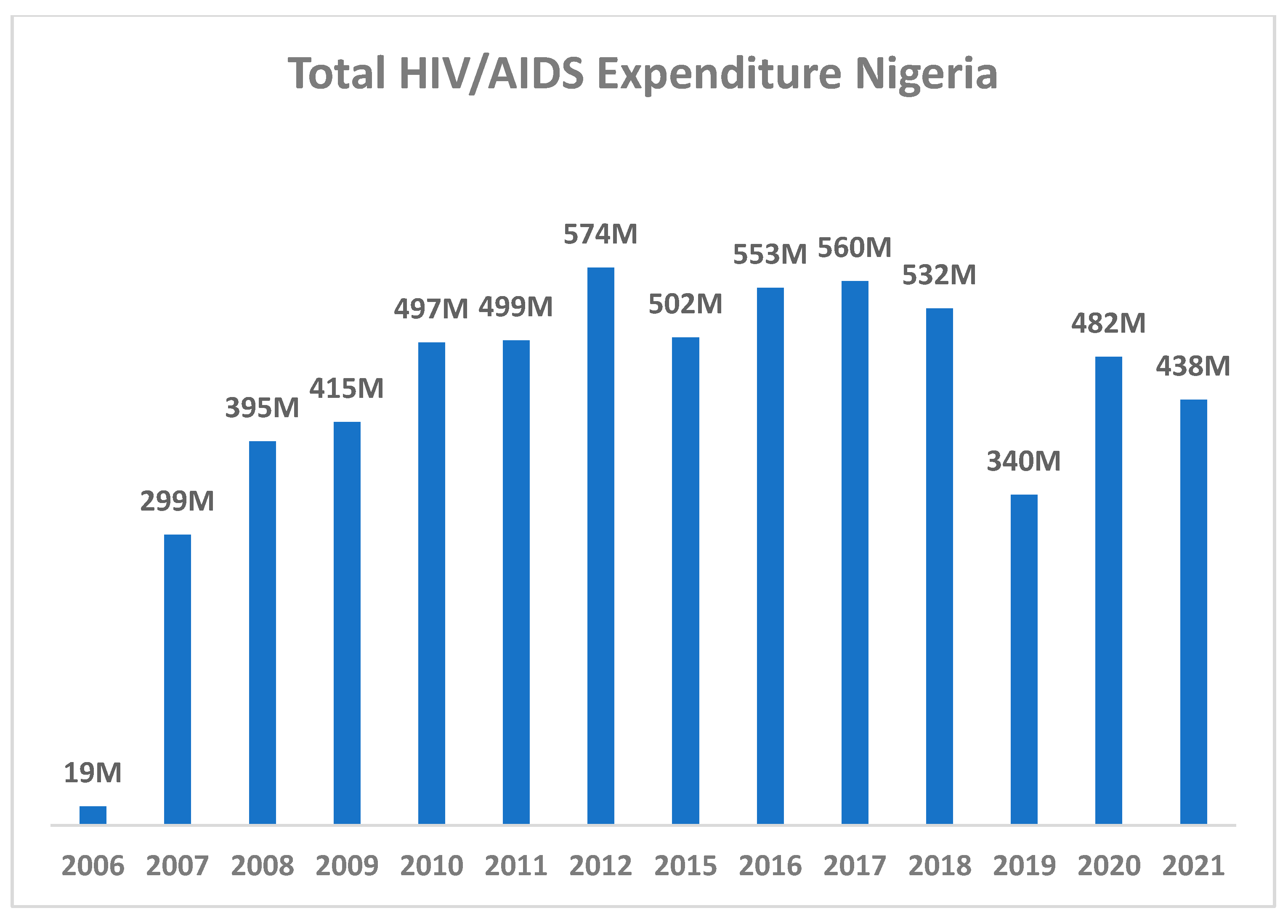

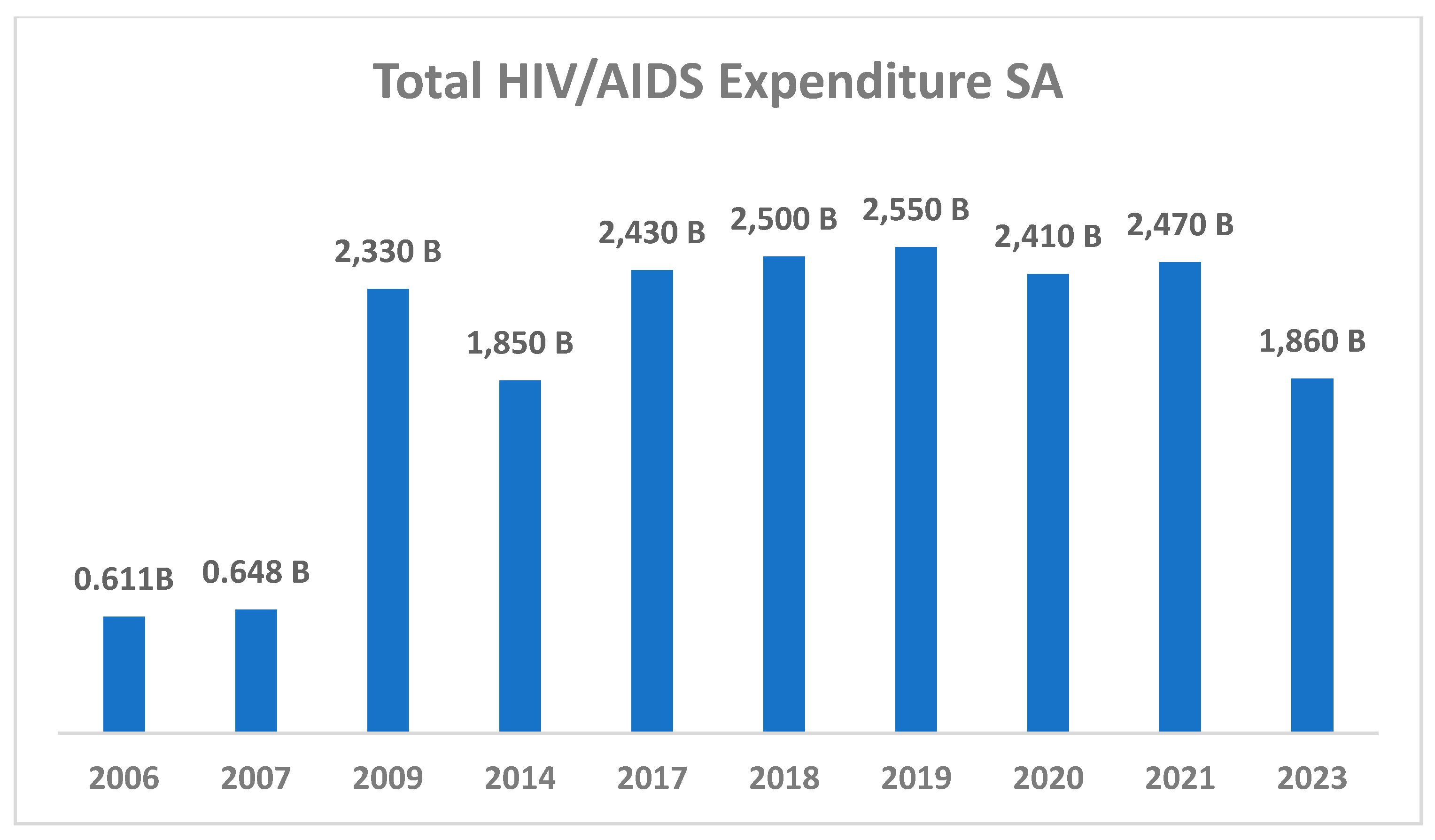

2. HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Trends in South Africa and Nigeria

3. Overview of the Contributions of United States (U.S.) Foreign Aid in the Fight Against HIV/AIDS in South Africa and Nigeria

4. The 20 January 2025, U.S. Government Foreign Aid Suspension

5. The Impact of Foreign Aid Suspension on Ongoing HIV/AIDS Prevention Initiatives, Specific Programs Affected, and Populations at Risk in South Africa and Nigeria

6. Comprehensive Public Health Impacts of the U.S. Foreign Aid Suspension

7. Mitigation Strategies to Be Adopted by South Africa and Nigeria

8. Recommendations for Ensuring National Widespread Availability and Adherence to HIV Initiatives

9. Discussion and Conclusions

9.1. Limitations

9.2. Epilogue

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global HIV/AIDS Overview|HIV.gov. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/pepfar-global-aids/global-hiv-aids-overview (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- United Nations. Progress at the Halfway Mark to the 2025 Milestones; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 22–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Statistics|HIV.gov. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/global-statistics (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Global HIV Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hiv/prevention/pre-exposure-prophylaxis (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Cowan, E.; Kerr, C.A.; Fernandez, A.; Robinson, L.-G.; Fayorsey, R.; Vail, R.M.; Shah, S.S.; Fine, S.M.; McGowan, J.P.; Merrick, S.T.; et al. PEP to Prevent HIV Infection; Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tenofovir Disoproxil/Emtricitabine for PrEP|aidsmap. Available online: https://www.aidsmap.com/about-hiv/tenofovir-disoproxil-emtricitabine-prep (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)|Aidsmap. Available online: https://www.aidsmap.com/about-hiv/post-exposure-prophylaxis-pep (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- WHO. Guidelines for HIV Post-Exposure Prophylaxis; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Fact Sheet 2024-Latest Global and Regional HIV Statistics on the Status of the AIDS Epidemic; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oosthuizen, A. SABSSM VI: An evolving epidemic with persistent challenges. HSRC Rev. 2024, 22, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria Prevalence Rate-NACA Nigeria. Available online: https://naca.gov.ng/nigeria-prevalence-rate/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- South Africa|UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Nigeria|UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/nigeria (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- At a Glance: HIV in South Africa|Be in the KNOW. Available online: https://www.beintheknow.org/understanding-hiv-epidemic/data/glance-hiv-south-africa (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- At a Glance: HIV in Nigeria|Be in the KNOW. Available online: https://www.beintheknow.org/understanding-hiv-epidemic/data/glance-hiv-nigeria (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Experts Warn of HIV Crisis as PEPFAR Funds Paused-Health-e News. Available online: https://health-e.org.za/2025/01/31/experts-warn-of-hiv-crisis-as-pepfar-funds-paused/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Sustaining HIV AIDS Intervention in Nigeria Towards Achieving the 2030 Global Target-Nigeria Health Watch. Available online: https://articles.nigeriahealthwatch.com/sustaining-hiv-aids-intervention-in-nigeria-towards-achieving-the-2030-global-target/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Eluwa, G.I.E.; Adebajo, S.B.; Eluwa, T.; Ogbanufe, O.; Ilesanmi, O.; Nzelu, C. Rising HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men in Nigeria: A trend analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanuel, F.; Ejeckam, C.C.; Green, K.; Adesina, A.A.; Aliyu, G.; Ashefor, G.; Aguolu, R.; Isac, S.; Blanchard, J. HIV epidemic among key populations in Nigeria: Results of the integrated biological and behavioural surveillance survey (IBBSS), 2020-2021. Sex Transm Infect. 2025, 101, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Republic of South Africa National Strategic Plan for HIV, TB and STIs, 2023; South African National AIDS Council (SANAC): Pretoria, South Africa, 2023; Volume 5, pp. 1–237. Available online: https://sanac.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/SANAC-NSP-2023-2028-Web-Version.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA). Country Progress Report-Nigeria Global AIDS Monitoring. 2020. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/NGA_2020_countryreport.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Murewanhema, G.; Musuka, G.; Moyo, P.; Moyo, E.; Dzinamarira, T. HIV and adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa: A call for expedited action to reduce new infections. IJID Reg. 2022, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). How Africa Turned AIDS Around; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 9789292530242. [Google Scholar]

- Amplifying Successes Case Studies from Eastern and Southern Africa; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Terefe, B.; Jembere, M.M. Discrimination against HIV/AIDS patients and associated factors among women in East African countries: Using the most recent DHS data (2015–2022). J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 22 USC 2151b-2: Assistance to Combat HIV/AIDS. Available online: https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=granuleid:USC-prelim-title22-section2151b-2&num=0&edition=prelim (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Moyo, E.; Moyo, P.; Murewanhema, G.; Mhango, M.; Chitungo, I.; Dzinamarira, T. Key populations and Sub-Saharan Africa’s HIV response. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1079990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyden, T.W.; Vogt, E.; Ng, A.K.; Johnson, P.M.; Rote, N.S. Monoclonal antiphospholipid antibody reactivity against human placental trophoblast. J. Reprod. Immunol. 1992, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIDS-AMERICA’S GIFT TO AFRICA?-Cybereagles. Available online: https://forum.cybereagles.com/viewtopic.php?t=28755 (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- Saag, M.S.; Gandhi, R.T.; Hoy, J.F.; Landovitz, R.J.; Thompson, M.A.; Sax, P.E.; Smith, D.M.; Benson, C.A.; Buchbinder, S.P.; Del Rio, C.; et al. Antiretroviral Drugs for Treatment and Prevention of HIV Infection in Adults: 2020 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society–USA Panel. JAMA 2020, 324, 1651–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, D.; Meghij, J.; Negussi, E.K.; Baggaley, R.C.; Ford, N.; Kranzer, K. Interventions to improve or facilitate linkage to or retention in pre-ART (HIV) care and initiation of ART in low- and middle-income settings—A systematic review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2014, 17, 19032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCree, D.H.; Young, S.R.; Henny, K.D.; Cheever, L.; McCray, E.U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Health Resources and Services Administration Initiatives to Address Disparate Rates of HIV Infection in the South. AIDS Behav. 2019, 23 (Suppl. S3), 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.E. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Policy Process and the Conversation around HIV/AIDS in the United States. J. Dev. Policy Pract. 2020, 5, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, R.J.; Sangmanee, D.; Piergallini, L. PEPFAR Funding and Reduction in HIV Infection Rates in 12 Focus Sub-Saharan African Countries: A Quantitative Analysis. Int. J. Matern. Child Health AIDS (IJMA) 2015, 3, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)|KFF. Available online: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-u-s-presidents-emergency-plan-for-aids-relief-pepfar/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief-United States Department of State %. Available online: https://www.state.gov/pepfar/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- IAS Statement: PEPFAR Freeze Threatens Millions of Lives|International AIDS Society (IAS). Available online: https://www.iasociety.org/ias-statement/pepfar-freeze-threatens-millions-lives (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- PEPFAR|HIV.gov. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/pepfar-global-aids/pepfar (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- 2017 Annual Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/PEPFAR-FY2013-COP-Guidance-Final.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- UNAIDS & World Health Organisation (WHO). Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Progress Report Steady Progress in the Scale Up of VMMC as an HIV Prevention Intervention in 15 Eastern and Southern African Countries Before the SARsCoV2 Pandemic; UNAIDS & World Health Organisation (WHO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- New HIV Survey Highlights Progress and Ongoing Disparities in South Africa’s HIV Epidemic-HSRC. Available online: https://hsrc.ac.za/press-releases/phsb/new-hiv-survey-highlights-progress-and-ongoing-disparities-in-south-africas-hiv-epidemic/ (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- DA Calls for Immediate Restoration of PEPFAR Programming to Avert a National Health Emergency. Available online: https://www.da.org.za/2025/01/da-calls-for-immediate-restoration-of-pepfar-programming-to-avert-a-national-health-emergency (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- South Africa-Trump Land Row May Move from Aid to Trade. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cm27g2jzd78o (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Nigeria and Global Fund Launch New Grants to Reinforce Progress against HIV, TB and Malaria-Updates-The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Available online: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/updates/2024/2024-02-05-nigeria-global-fund-launch-new-grants-reinforce-progress-against-hiv-tb-malaria/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Nigeria Strengthens Fight Against HIV, TB, and Malaria with $933 Million Global Fund Grant » News.ng. Available online: https://news.ng/nigeria-strengthens-fight-against-hiv-tb-and-malaria-with-933-million-global-fund-grant/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Nigeria Receives $890m from Global Fund to fight HIV, Malaria, Tuberculosis. Available online: https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/07/nigeria-receives-890m-from-global-fund-to-fight-hiv-malaria-tuberculosis/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- South Africa-Government and Public Donors-The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Available online: https://www.theglobalfund.org/en/government/profiles/south-africa (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Mukherjee, T.I.; Yep, M.; Koluch, M.; Abayneh, S.A.; Eyassu, G.; Manfredini, E.; Herbst, S. Disparities in PrEP use and unmet need across PEPFAR-supported programs: Doubling down on prevention to put people first and end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. Front. Reprod. Health 2024, 6, 1488970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saul, J.; Bachman, G.; Allen, S.; Toiv, N.F.; Cooney, C.; Beamon, T. The DREAMS core package of interventions: A comprehensive approach to preventing HIV among adolescent girls and young women. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa, S.; World, O.; Day, A.; Plan, E.; Relief, A.; Agyw, S.; Nextgen, D.; Nextgen, D.; Hiv, R.; Nextgen, D. Dreams Is not a Moment, IT Is a Movement. 2023. Available online: https://www.prepwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Oct_22_2020_PrEPLearningNetwork_DREAMS.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Allinder, S.M.; Fleischman, J. The World’s Largest HIV Epidemic in Crisis: HIV in South Africa; Center for Strategic and International Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Guidance on Criteria and Processes for Validation: Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV and Syphilis Monitoring; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 143, ISBN 9789240039360. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, C.; Luies, L. WHO Goals and Beyond: Managing HIV/TB Co-infection in South Africa. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2023, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEPFAR Country/Regional Operational Plans (COPs/ROPs) Database, amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research. Available online: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/PEPFAR-2023-Country-and-Regional-Operational-Plan.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- AIDSinfo|UNAIDS. Available online: https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- From the Darkest of Days to a New Dawn Archives—Nigeria Health Watch. Available online: https://articles.nigeriahealthwatch.com/tag/from-the-darkest-of-days-to-a-new-dawn/ (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Okoroiwu, H.U.; Umoh, E.A.; Asanga, E.E.; Edet, U.O.; Atim-Ebim, M.R.; Tangban, E.A.; Mbim, E.N.; Odoemena, C.A.; Uno, V.K.; Asuquo, J.O.; et al. Thirty-five years (1986–2021) of HIV/AIDS in Nigeria: Bibliometric and scoping analysis. AIDS Res. Ther. 2022, 19, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEPFAR-U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Nigeria. Available online: https://ng.usembassy.gov/pepfar/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- National Agency for the Control of AIDS. National Agency for the Control of AIDS Revised National HIV and AIDS Strategic Framework: 2021; National Agency for the Control of AIDS: Abuja, Nigeria, 2021; Volume 8, pp. 15–20.

- PEPFAR Mozambique Country Operational Plan 2023 Strategic Direction Summary. 2023. Available online: https://mz.usembassy.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/143/2023/09/2023-Strategic-Direction-Summary.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- NACA GLOBAL AIDS RESPONSE Country Progress Report NIGERIA. 2014, pp. 24–26. Available online: https://za.usembassy.gov/presidents-emergency-plan-for-aids-relief-pepfar-status-frequently-asked-questions/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- PEPFAR Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting Database. Available online: https://mer.amfar.org/location/Nigeria (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). Status Frequently Asked Questions-U.S. Embassy & Consulates in South Africa. Available online: https://za.usembassy.gov/presidents-emergency-plan-for-aids-relief-pepfar-status-frequently-asked-questions/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Nigeria PEPFAR | MHRP. Available online: https://hivresearch.org/pepfar/nigeria-pepfar (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- USAID Funding Cuts End Vital HIV Programme for Orphans • Spotlight. Available online: https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2025/03/03/usaid-funding-cuts-end-vital-hiv-programme-for-orphans/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Nigeria|USAID Global Health Supply Chain Program. Available online: https://www.ghsupplychain.org/country-profile/nigeria (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- CDC Global Health-South Africa-What CDC Is Doing. Available online: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/globalhealth/countries/southafrica/what/default.htm (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- CDC in Nigeria|Global Health|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/global-health/countries/nigeria.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Implementing the President’s Executive Order on Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid-U.S. Embassy & Consulates in South Africa. Available online: https://za.usembassy.gov/implementing-the-presidents-executive-order-on-reevaluating-and-realigning-united-states-for/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- The Status of President Trump’s Pause of Foreign Aid and Implications for PEPFAR and Other Global Health Programs|KFF. Available online: https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/the-status-of-president-trumps-pause-of-foreign-aid-and-implications-for-pepfar-and-other-global-health-programs/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- The Impact of The U.S. Government’s Presidency on International Development. An Analysis. Available online: https://focus2030.org/The-impact-of-Donald-Trump-s-presidency-on-international-development-An (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Ranking Members Shaheen, Schatz, Meeks, Frankel: We…. Available online: https://www.foreign.senate.gov/press/dem/release/ranking-members-shaheen-schatz-meeks-frankel-we-cannot-afford-to-take-a-timeout-from-usaid-programs (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Senator Coons Decries President Trump’s Freeze on Almost all Foreign Assistance in Speech on SENATE Floor. Available online: https://www.coons.senate.gov/news/press-releases/senator-coons-decries-president-trumps-freeze-on-almost-all-foreign-assistance-in-speech-on-senate-floor (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Kwaan, L.; Kindra, G.; Mdutyana, L.; Coutsoudis, A. Prevention is better than cure—The art of avoiding non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment. S. Afr. J. HIV Med. 2010, 11, 8–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Health Organization. WHO Progress Report 2016 Prevent HIV, Test and Treat All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Rautenbach, S.P.; Whittles, L.K.; Meyer-Rath, G.; Jamieson, L.; Chidarikire, T.; Johnson, L.F.; Imai-Eaton, J.W. Future HIV epidemic trajectories in South Africa and projected long-term consequences of reductions in general population HIV testing: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2024, 9, e218–e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detels, R.; Wu, J.; Wu, Z. Control of HIV/AIDS can be achieved with multi-strategies. Glob. Health J. 2019, 3, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akingbola, A.; Adegbesan, A.; Mariaria, P.; Isaiah, O.; Adeyemi, E. A pause that hurts: The global impact of halting PEPFAR funding for HIV/AIDS programs. Infect. Dis. (Auckl.) 2025, 57, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impact of Recent U.S. Shifts on the Global HIV Response—The Global Impact of PEPFAR to Date|UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/topic/PEPFAR_impact (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- PEPFAR. Annual Report to Congress The United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief 2022 Annual Report to Congress. 2022; pp. 1–118. Available online: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/PEPFAR2022.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Bendavid, E. Past and Future Performance: PEPFAR in the Landscape of Foreign Aid for Health. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016, 13, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walensky, R.P.; Borre, E.D.; Bekker, L.G.; Hyle, E.P.; Gonsalves, G.S.; Wood, R.; Eholié, S.P.; Weinstein, M.C.; Anglaret, X.; Freedberg, K.A.; et al. Do less harm: Evaluating HIV programmatic alternatives in response to cutbacks in foreign aid. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 618–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, A. From the American People: An Autoethnographic Exploration of South African NGOs’ Perceptions of PEPFAR. 2019. Available online: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4041&context=isp_collection/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- HIV and AIDS Financing in South Africa: Sustainability and Fiscal Space|South African Health Review. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC189307 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Milimu, J.W.; Parmley, L.; Matjeng, M.; Madibane, M.; Mabika, M.; Livington, J.; Lawrence, J.; Motlhaoleng, O.; Subedar, H.; Tsekoa, R.; et al. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation in South Africa: A case study of USAID-supported programs. Front. Reprod. Health 2024, 6, 1473354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USAid-Funded HIV Organisations in SA Struggle to Return to Work. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2025-02-17-usaid-funded-hiv-organisations-in-sa-struggle-to-return-to-work-despite-us-court-ruling/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Our Work|South Africa|Archive-U.S. Agency for International Development. Available online: https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2025/02/14/no-clear-government-plan-yet-to-confront-us-aid-cuts/#:~:text=According%20to%20USAID's%20website%2C%20it,halted%20funding%20received%20via%20USAID (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- A Review of Health, HIV and TB Resource Allocation and Utilisation in South Africa 2013/14-2020/21|South African Health Review. Available online: https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC-1d2b1bb8bb (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Trump’s Funding Freeze Threatens to Paralyse SA NGOs-Juta MedicalBrief. Available online: https://www.medicalbrief.co.za/trumps-funding-freeze-paralyses-sa-ngos/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Morris, M. Trump freezes funds and Africa counts the costs. In Nature Africa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAQ on PEPFAR status-DOCUMENTS|Politicsweb. Available online: https://www.politicsweb.co.za/documents/faq-on-pepfar-status (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- No Clear Government Plan Yet to Confront US Aid CUTS • Spotlight. Available online: https://www.spotlightnsp.co.za/2025/02/14/no-clear-government-plan-yet-to-confront-us-aid-cuts/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Media Statement: Committee on Health Briefed on Pepfar Funding Withdrawal and Employment of Healthcare Professionals-Parliament of South Africa. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/press-releases/media-statement-committee-health-briefed-pepfar-funding-withdrawal-and-employment-healthcare-professionals (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- PEPFAR: 20 Years of Impact-U.S. Embassy and Consulate in Nigeria. Available online: https://ng.usembassy.gov/pepfar-20-years-of-impact/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Banigbe, B.; Audet, C.M.; Okonkwo, P.; Arije, O.O.; Bassi, E.; Clouse, K.; Simmons, M.; Aliyu, M.H.; Freedberg, K.A.; Ahonkhai, A.A. Effect of PEPFAR funding policy change on HIV service delivery in a large HIV care and treatment network in Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhlongolwane, N.; Shonisani, T. Predictors and Barriers Associated with Non-Adherence to ART by People Living with HIV and AIDS in a Selected Local Municipality of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Open AIDS J. 2024, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadi, T.L.; Wiemers, A.M.C.; Tegene, Y.; Medhin, G.; Spigt, M. Experiences of people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries and their perspectives in self-management: A meta-synthesis. AIDS Res. Ther. 2024, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masquillier, C.; Wouters, E.; Mortelmans, D.; Van Wyk, B.; Hausler, H.; Van Damme, W. HIV/AIDS Competent Households: Interaction between a Health-Enabling Environment and Community-Based Treatment Adherence Support for People Living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0151379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutabazi, J.C.; Zarowsky, C.; Trottier, H. The impact of programs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV on health care services and systems in sub-Saharan Africa—A review. Public Health Rev. 2017, 38, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro Banze, Á.; Muleia, R.; Nuvunga, S.; Boothe, M.; Semá Baltazar, C. Trends in HIV prevalence and risk factors among men who have sex with men in Mozambique: Implications for targeted interventions and public health strategies. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyrer, C.; Baral, S.D.; Collins, C.; Richardson, E.T.; Sullivan, P.S.; Sanchez, J.; Trapence, G.; Katabira, E.; Kazatchkine, M.; Ryan, O.; et al. The global response to HIV in men who have sex with men. Lancet 2016, 388, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oginni, O.A.; Adelola, A.I.; Ogunbajo, A.; Opara, O.J.; Akanji, M.; Ibigbami, O.I.; Afolabi, O.T.; Akinsulore, A.; Mapayi, B.M.; Mosaku, S.K. Antiretroviral therapy non-adherence and its association with psychosocial factors in Nigeria: Comparative study of sexual minority and heterosexual men living with HIV. AIDS Care 2024, 36, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowell, T.A.; Keshinro, B.; Baral, S.D.; Schwartz, S.R.; Stahlman, S.; Nowak, R.G.; Adebajo, S.; Blattner, W.A.; Charurat, M.E.; Ake, J.A. Stigma, access to healthcare, and HIV risks among men who sell sex to men in Nigeria. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awofala, A.A.; Ogundele, O.E. HIV epidemiology in Nigeria. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigeria Announces Measures to Soften Impact of USAID Programs’ Suspension. Available online: https://www.voanews.com/a/nigeria-announces-measures-to-soften-impact-of-usaid-programs-suspension/7962960.html (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Nigerian Lawmakers Approve $200 Million to Offset Shortfall from US Health Aid Cuts. Available online: https://www.usnews.com/news/world/articles/2025-02-14/nigerian-lawmakers-approve-200-million-to-offset-shortfall-from-us-health-aid-cuts (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Onovo, A.A.; Adeyemi, A.; Onime, D.; Kalnoky, M.; Kagniniwa, B.; Dessie, M.; Lee, L.; Parrish, D.; Adebobola, B.; Ashefor, G.; et al. Estimation of HIV prevalence and burden in Nigeria: A Bayesian predictive modelling study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 62, 102098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, N.E.; Shook-Sa, B.E.; Liu, M.; Stranix-Chibanda, L.; Yotebieng, M.; Sam-Agudu, N.A.; Hudgens, M.G.; Phiri, S.J.; Mutale, W.; Bekker, L.G.; et al. Adult HIV-1 incidence across 15 high-burden countries in sub-Saharan Africa from 2015-2019: Pooled nationally representative estimates. Lancet HIV 2023, 10, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, E. ‘It is chaos’: US funding freezes are endangering global health. Nature 2025, 638, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “I don’t want to die”: Trump’s Aid Plans Raise Fear in Africa-CNBC Africa. Available online: https://www.cnbcafrica.com/2025/i-dont-want-to-die-trumps-aid-plans-raise-fear-in-africa/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- HIV Clinics Close Across Africa After US Issues ‘Stop-Work Order’ To All Aid Recipients—Health Policy Watch. Available online: https://healthpolicy-watch.news/hiv-clinics-close-across-africa-after-trump-administration-issues-stop-work-order/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Muessig, K.E.; Cohen, M.S. Advances in HIV Prevention for Serodiscordant Couples. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump’s Sudden Suspension of Foreign Aid Puts Millions of Lives in Africa at Risk. Available online: https://www.eatg.org/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- South African NGOs worry Trump’s Aid Freeze Will Impact HIV Treatment|AP News. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/south-africa-trump-pepfar-hiv-aid-freeze-0d9def2a63b0e2f53bfda9441baf584d (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Drake, A.L.; Thomson, K.A.; Quinn, C.; Newman Owiredu, M.; Nuwagira, I.B.; Chitembo, L.; Essajee, S.; Baggaley, R.; Johnson, C.C. Retest and treat: A review of national HIV retesting guidelines to inform elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission (EMTCT) efforts. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2019, 22, e25271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelekan, B.; Harry-Erin, B.; Okposo, M.; Aliyu, A.; Ndembi, N.; Dakum, P.; Sam-Agudu, N.A. Final HIV status outcome for HIV-exposed infants at 18 months of age in nine states and the Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.; Giddy, J.; Stinson, K. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission in South Africa: An ever-changing landscape. Obstet. Med. 2015, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumah, E.; Boakye, D.S.; Boateng, R.; Agyei, E. Advancing the Global Fight Against HIV/Aids: Strategies, Barriers, and the Road to Eradication. Ann. Glob. Health 2023, 89, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Key Population Groups, Including Gay Men and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men, Sex Workers, Transgender People and People Who Inject Drugs|UNAIDS. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/en/topic/key-populations (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Martinson, N.A.; Hoffmann, C.J.; Chaisson, R.E. Epidemiology of Tuberculosis and HIV: Recent Advances in Understanding and Responses. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2011, 8, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundareshan, V.; Swinkels, H.M.; Nguyen, A.D.; Mangat, R.; Koirala, J. Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention. StatPearls 2024. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507789/ (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Swinkels, H.M.; Vaillant, A.A.J.; Nguyen, A.D.; Gulick, P.G. HIV and AIDS. Geriatr. Gastroenterol. 2024, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M.M.; Daud, N.M. Exploring the Needs of the B40 Community in Agricultural Activities for Social Entrepreneur Activists. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 11, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Villiers, K. Bridging the health inequality gap: An examination of South Africa’s social innovation in health landscape. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2021, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press Releases-Parliament of South Africa. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/press-release (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Azevedo, M.J. The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. In Historical Perspectives on the State of Health and Health Systems in Africa, Volume II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; p. 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global HIV Prevention Coalition HIV PREVENTION 2025–ROAD MAP: Getting on Track to End AIDS as a Public Health Threat by 2030; Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Levi, J.; Pozniak, A.; Heath, K.; Hill, A. The impact of HIV prevalence, conflict, corruption, and GDP/capita on treatment cascades: Data from 137 countries. J. Virus Erad. 2018, 4, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raver, E.; Retchin, S.M.; Li, Y.; Carlo, A.D.; Xu, W.Y. Rural–urban differences in out-of-network treatment initiation and engagement rates for substance use disorders. Health Serv. Res. 2024, 59, e14299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, L.G.; Alleyne, G.; Baral, S.; Cepeda, J.; Daskalakis, D.; Dowdy, D.; Dybul, M.; Eholie, S.; Esom, K.; Garnett, G.; et al. Advancing global health and strengthening the HIV response in the era of the Sustainable Development Goals: The International AIDS Society—Lancet Commission. Lancet 2018, 392, 312–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslo Ministerial Declaration. Global health: A pressing foreign policy issue of our time. Lancet 2007, 369, 1373–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grebe, E. The Treatment Action Campaign’s Struggle for AIDS Treatment in South Africa: Coalition-building Through Networks. J. S. Afr. Stud. 2011, 37, 849–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.B.; Coggin, W.; Jamieson, D.; Mihm, H.; Granich, R.; Savio, P.; Hope, M.; Ryan, C.; Moloney-Kitts, M.; Goosby, E.P.; et al. Use of Generic Antiretroviral Agents and Cost Savings in PEPFAR Treatment Programs. JAMA 2010, 304, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, W.D.F.; Kaiser, B.; Pillay, Y.; Conradie, F.; Gomez, G.B.; Clayden, P.; Matsolo, M.; Amole, C.; Rutter, L.; Abdullah, F.; et al. Cutting the cost of South African antiretroviral therapy using newer, safer drugs. SAMJ S. Afr. Med. J. 2017, 107, 28–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CARISMAND. Secure Societies–Protecting Freedom and Security of Europe and Its CARISMAND Culture and RISk Management in Man-Made and Natural Disasters Report on “Risk Cultures” in the Context of Disasters. 2020; pp. 1–94. Available online: https://p.carismand.eu/t/c/a/carismand-d0401-ls2017-07-rf2018-09-52.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Brown, G.W.; Loewenson, R.; Modisenyane, M.; Papamichail, A.; Cinar, B. Business as usual? The role of BRICS cooperation in addressing health system priorities in East and Southern Africa. J. Health Dipl. 2015, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Modisenyane, S.M.; Hendricks, S.J.H.; Fineberg, H. Understanding how domestic health policy is integrated into foreign policy in South Africa: A case for accelerating access to antiretroviral medicines. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1339533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbuabor, D.; Olwande, C.; Semini, I.; Onwujekwe, O.; Olaifa, Y.; Ukanwa, C. Stakeholders’ Perspectives on the Financial Sustainability of the HIV Response in Nigeria: A Qualitative Study. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2023, 11, e2200430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, B.N.; Abimiku, C.A.; Dangiwa, D.A.; Umar, D.M.; Bulus, K.I.; Dapar, M.L.P. Foreign Aid Initiatives and the HIV/AIDS Epidemic in Nigeria: Perspectives on Country Ownership and Humanistic Care. Int. STD Res. Rev. 2017, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogart, J.P.; Calcagnotto, G.; Hein, W.; von Soest, C. AIDS, Access to Medicines, and the Different Roles of the Brazilian and South African Governments in Global Health Governance. SSRN Electron. J. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIDS Drugs For All: Social Movements and Market Transformations-Ethan B. Kapstein, Joshua W. Busby-Google Books. Available online: https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dZBfAAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=AIDS+Drugs+For+All:+Social+Movements+and+Market+Transformations+By+Ethan+B.+Kapstein,+Joshua+W.+Busb&ots=LVqam5KDP5&sig=QH1z5C7D9CJqRgm_vxdi1ryA83Q&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=AIDSDrugsForAll%3ASocialMovementsandMarketTransformationsByEthanB.Kapstein%2CJoshuaW.Busb&f=false (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Heywood, M. South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign: Combining Law and Social Mobilization to Realize the Right to Health. J. Hum. Rights Pract. 2009, 1, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RSA Mtsf 2019–2024. 2019; pp. 1–263. Available online: https://knowledgehub.health.gov.za/system/files/elibdownloads/2023-04/Role-of-QI-in-MTCT.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Gazete, G.; Notice, G. National Health Insurance Act 20 of 2023 (English/Afrikaans). 2024, Volume 707. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/acts/national-health-insurance-act-20-2023-english-afrikaans-16-may-2024 (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- SA Should Prepare for “Worst Case Scenario” After Trump Cuts-Juta MedicalBrief. Available online: https://www.medicalbrief.co.za/sa-should-prepare-for-worst-case-scenario-after-trump-cuts/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Oturu, K.; O’Brien, O.; Ozo-Eson, P.I. Barriers and enabling structural forces affecting access to antiretroviral therapy in Nigeria. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanduru, P.; Tetui, M.; Tuhebwe, D.; Ediau, M.; Okuga, M.; Nalwadda, C.; Ekirapa-Kiracho, E.; Waiswa, P.; Rutebemberwa, E. The performance of community health workers in the management of multiple childhood infectious diseases in Lira, northern Uganda-A mixed methods cross-sectional study. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapitsa, C.B.; Churchill, C. (Eds.) Monitoring Systems in Africa; African Sun Media: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vian, T. Anti-corruption, transparency and accountability in health: Concepts, frameworks, and approaches. Glob. Health Action 2020, 13, 1694744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.; Thompson, C. What steps can improve and promote investment in the health and care workforce in Europe? Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, ckad160-060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europe PMC. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/nbk/nbk525184 (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Emergency Humanitarian Waiver to Foreign Assistance Pause-United States Department of State. Available online: https://www.state.gov/emergency-humanitarian-waiver-to-foreign-assistance-pause-2/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Cuts to PEPFAR Spell Detrimental HIV Outcomes in South Africa. Available online: https://www.ajmc.com/view/cuts-to-pepfar-spell-detrimental-hiv-outcomes-in-south-africa (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Chiliza, J.; Brennan, A.T.; Laing, R.; Feeley, F.G., III. Evaluation of the impact of PEPFAR transition on retention in care in South Africa’s Western Cape. medRxiv 2023, 2023.01.20.23284819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainability of the HIV/AIDS Response–Getting to 2030 & Beyond-National Academy of Medicine. Available online: https://nam.edu/event/sustainability-of-the-hiv-aids-response-getting-to-2030-beyond/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Odeny, T.A.; Penner, J.; Lewis-Kulzer, J.; Leslie, H.H.; Shade, S.B.; Adero, W.; Kioko, J.; Cohen, C.R.; Bukusi, E.A. Integration of HIV Care with Primary Health Care Services: Effect on Patient Satisfaction and Stigma in Rural Kenya. AIDS Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 485715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primary Health Care and HIV: Convergent Actions. Policy Considerations for…-World Health Organization-Google Books. Available online: https://books.google.co.za/books?hl=en&lr=&id=QaIOEQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA22&dq=48.%09Organization+WH.+Primary+health+care+and+HIV:+convergent+actions.+Policy+considerations+for+decision-makers:+World+Health+Organization%3B+2023.&ots=oQ0Z_eaonS&sig=OgIhaCGU16ADwDrunpYpT7U1DBA&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- “From the American People: An Autoethnographic Exploration of South Afr” by Antonia Asher. Available online: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3023/ (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Cazenave, B.; Morales, J. NGO responses to financial evaluation: Auditability, purification and performance. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2021, 34, 731–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fund, T.G.; Fund, G.; Office, T.; General, I.; Fund, G.; Fund, G.; Fund, G.; Fund, T.G. Archive PDF. 2016; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/2656/oig_gf-oig-16-015_report_en.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- National Department of Health (South Africa). National Department of Health ANNUAL Report 2020/21; National Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020; ISBN 9780621497120.

- Ooms, G.; Kruja, K. The integration of the global HIV/AIDS response into universal health coverage: Desirable, perhaps possible, but far from easy. Glob. Health 2019, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trump Orders Immediate end to USAID Funding for HIV Organisations in SA|News24. Available online: https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/trump-orders-immediate-end-to-usaid-funding-for-hiv-organisations-in-sa-20250227 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Trump Unleashes ‘Tiger from Cage’ on SA’s HIV Battle. Available online: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/health/2025-02-27-trump-unleashes-tiger-from-cage-on-sas-hiv-battle/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Trump: “Thank You for Partnering with USAID and God Bless America.”-Bhekisisa. Available online: https://bhekisisa.org/health-news-south-africa/2025-02-27-breaking-trump-orders-usaid-funded-hiv-organisations-in-sa-to-shut-down/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- SA-US Relations|Trump Shuts Down USAID Funding Permanently-eNCA. Available online: https://www.enca.com/news/sa-us-relations-trump-shuts-down-usaid-funding-permanently (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- USAID Issues Funding Termination Notices to Key SA Health Programmes. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2025-02-27-the-axe-has-fallen-usaid-issues-funding-termination-notices-to-key-health-programmes-across-sa/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

| PLHIV | New HIV Infections | HIV-Related Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistics/Total Number | 39.9 million | 1.3 million | 630,000 |

| Adults above 15 years | 38.6 million | 1.2 million | 560,000 |

| Children below 15 years | 1.4 million | 120,000 | 76,000 |

| Men above 15 years | 18.1 million | 660,000 | 320,000 |

| Women above 15 years | 20.5 million | 520,000 | 240,000 |

| Features | PREP | PEP |

|---|---|---|

| Aim | Prevention of HIV prior to exposure | Prevention of HIV after exposure |

| Medication Schedule | Continuous and daily | After exposure |

| Period | Prolonged as required | Only a 28-day regimen |

| Efficiency | About 99% on when strictly adhered to | Approximately 80% if taken within 72 h after exposure |

| Targets | Vulnerable populations | To be taken by everybody when exposed to HIV |

| Compliance | Strict daily compliance | Strict daily 28 days of compliance |

| Drug Reactions | Very moderate, likely liver and kidney malfunctions | Interim nauseating symptoms, stomach upset, and weakness |

| Availability | Usually prescribed and needs constant follow up | Only in emergencies |

| Group/Class | South Africa | Nigeria | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV prevalence adults: 15–49 years | 19.6% | 1.3% | [10,11] |

| Number of PLHIV | 7.8 million | 1.8 million | [10,11] |

| Yearly new infections | 150,000 | 75,000 | [12,13] |

| Yearly HIV/AIDS-related mortality | 45,000 | 51,000 | [14,15] |

| PEPFAR ART coverage | 5.5 million persons on treatment | 1.7 million persons on treatment | [16,17] |

| Main vulnerable populations | MSM, sex workers, transgender people, people who inject drugs (PWID), adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) | MSM, sex workers, transgender people, people who inject drugs (PWID), adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) | [18,19,20,21,22] |

| Major contributors to HIV epidemic | Stigmatization and other socio-economic discrimination, reduced proportion of male circumcisions, high gender-based violence (GBV) | Stigmatization and other socio-economic discrimination, insufficient accessibility of HIV test kits and treatment, and gender inequality | [23,24,25] |

| Funding Agency | Main Activities in South Africa | Main Activities in Nigeria | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) | Mainly funded and supported antiretroviral therapy and other HIV-preventive programs, supporting laboratory equipment and system strengthening | Mainly funded and supported antiretroviral therapy and other HIV-preventive programs, supporting laboratory equipment and system strengthening | [63,64] |

| U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) | Bilateral assistance with focus on orphans, vulnerable children, prevention programs, health systems | Focus on prevention, care for vulnerable groups, supply chains, and strengthening of health systems | [65,66] |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) | Provision of technical assistance, surveillance, monitoring, and strengthening of public health capacity | Supporting laboratory activities, data and system record keeping, epidemiology training of health workforce, and other implementation of other HIV programs | [67,68] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ugbaja, S.C.; Setlhare, B.; Atiba, P.M.; Kumalo, H.M.; Ngcobo, M.; Gqaleni, N. The Public Health Impact of Foreign Aid Withdrawal by the United States Government and Its Implications for ARVs, Preexposure, and Postexposure Prophylaxis Medications in South Africa and Nigeria. World 2025, 6, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020074

Ugbaja SC, Setlhare B, Atiba PM, Kumalo HM, Ngcobo M, Gqaleni N. The Public Health Impact of Foreign Aid Withdrawal by the United States Government and Its Implications for ARVs, Preexposure, and Postexposure Prophylaxis Medications in South Africa and Nigeria. World. 2025; 6(2):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020074

Chicago/Turabian StyleUgbaja, Samuel Chima, Boitumelo Setlhare, Peterson Makinde Atiba, Hezekiel M. Kumalo, Mlungisi Ngcobo, and Nceba Gqaleni. 2025. "The Public Health Impact of Foreign Aid Withdrawal by the United States Government and Its Implications for ARVs, Preexposure, and Postexposure Prophylaxis Medications in South Africa and Nigeria" World 6, no. 2: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020074

APA StyleUgbaja, S. C., Setlhare, B., Atiba, P. M., Kumalo, H. M., Ngcobo, M., & Gqaleni, N. (2025). The Public Health Impact of Foreign Aid Withdrawal by the United States Government and Its Implications for ARVs, Preexposure, and Postexposure Prophylaxis Medications in South Africa and Nigeria. World, 6(2), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/world6020074