Abstract

Protected areas (PAs) are essential for conserving biodiversity and supporting sustainable development, particularly in ecologically rich yet administratively challenged regions like Romania. This study aims to understand how key stakeholders—local residents and protected area administrators—experience and interpret conservation management in the Southwestern Carpathians, one of Europe’s last remaining large-scale wilderness areas. Using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA), the research offers an in-depth qualitative investigation into how individuals perceive, navigate, and negotiate conservation regulations, socio-economic pressures, and sustainable development goals. The findings highlight a deep emotional connection between residents and nature, juxtaposed with tensions over restrictions, perceived loss of autonomy, and limited compensation. Administrators, in turn, face challenges in enforcing regulations, managing tourism, and engaging communities amidst institutional fragmentation and resource constraints. Key findings emphasize the importance of environmental education, trust-building, and participatory governance in reconciling conservation aims with local development needs. The study underscores the need for inclusive, context-sensitive conservation strategies that integrate community perspectives and facilitate cooperation among local authorities, residents, and administrators. These insights contribute to a deeper understanding of stakeholder dynamics and policy implementation within protected areas, emphasizing the importance of co-produced knowledge and adaptive governance. Future research is encouraged to adopt participatory action approaches and expand stakeholder diversity to support more socially inclusive and ecologically resilient conservation practices.

1. Introduction

All countries that signed the Convention on Biological Diversity [1] recognize that protected areas are the most crucial method for preserving biodiversity and offering models for sustainable development in harmony with nature, particularly given the rapid economic growth of recent decades [2].

Protected areas play a vital role in preserving natural and cultural capital. They safeguard the most representative and significant areas for biodiversity, natural values, and cultural heritage, making them one of the most effective strategies for preventing biodiversity loss and halting the degradation of forests and other natural habitats [3,4,5]. These areas are managed to maintain and, where necessary, restore natural ecosystems and populations of wild species while striving for the sustainable use of natural resources.

As Dearden and colleagues [6] emphasize, protected areas form a cornerstone of global conservation efforts. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a protected area as a “clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated, and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values” [7] (p. 2). Beyond biodiversity conservation, protected areas deliver a wide range of ecosystem services [8] (p. 1), such as “food, building materials, medicines, climate regulation, disease prevention, provision of clean air, water, soils, and landscape for cultural services and spiritual purpose”.

Woodley and colleagues [5] highlight that Aichi Biodiversity Target has been one of the most successfully implemented aspects of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity [9], fueling momentum toward adopting more ambitious protected area targets.

1.1. Biodiversity and Conservation Context—Romania

Romania, covering nearly 238,000 km2 of land and more than 29,500 km2 of marine area [10], is the most biogeographically diverse country in the European Union (EU), representing 5 out of the 11 EU-recognized regions: alpine, continental, Pannonian, Pontic, and steppe. With 1572 protected areas (PAs) spanning 71,254 km2, over 25% of the country’s surface enjoys legal protection [9,10]. Romania’s total area is almost evenly divided among mountains, hills, plateaus, plains, and meadows. The country’s varied flora and fauna result from the complexity of its terrain.

Romania features extensive areas of intact natural ecosystems and landscapes, and one of the most diverse ranges of EU, national, and internationally protected species and habitats. These include over 700 km2 of pristine and semi-pristine forests, 33% of Europe’s brown bear population (Ursus arctos), 25% of its wolves (Canis lupus), and significant populations of the Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), exceeding those in many other EU countries [11]. The government also promotes a high level of farmland biodiversity [12].

However, as one of the EU’s newest members and still grappling with the lasting impact of decades of communist rule, Romania faces significant developmental challenges. These include corruption, low quality of life, weak civil society organizations, limited participatory governance, and insufficient environmental policies.

Stringer and Paavlova [13] identify one of the causes as “a lack of historical involvement of communities in decision making” and highlight the need for a more inclusive and multi-stakeholder approach to achieve environmental objectives effectively (p. 138). Romania’s high biodiversity results from complex social–ecological interactions within a diverse natural context. This biodiversity has been shaped by historical political regimes, a slower pace of development, effective regenerative forestry and wildlife management practices, and traditional ecological methods prevalent in its predominantly rural areas. However, these natural assets are increasingly at risk due to the country’s rapid and often chaotic development within the EU’s open-border framework, alongside weakened institutions and limited civic engagement.

In Romania, national legislation—specifically, Emergency Ordinance No. 57/2007 concerning the regime of protected natural areas, the conservation of natural habitats, and the protection of wild flora and fauna—defines a protected natural area as follows: “a terrestrial and/or marine area containing wild species and animals, biogeographical, landscape, geological, paleontological, or other natural elements and formations of exceptional ecological, scientific, or cultural value, which is subject to a special regime of protection and conservation established in accordance with legal provisions” [2] (p. 6).

Biodiversity conservation practices are typically understood and classified by considering the specific management objectives of particular areas, which the IUCN standardizes. According to the WWF Guide for Initiating Procedures to Prevent and Stop Activities with Negative Impacts on Nature [2], protected areas may have one or more management objectives: “Scientific research; Wilderness protection (areas without human intervention)–excluding any form of natural resource exploitation that conflicts with management objectives; Protection of species diversity and genetic diversity; Maintenance of environmental services; Protection of natural and cultural features; Tourism and recreation; Education; Sustainable use of natural resources and ecosystems; and Preservation of cultural and traditional activities” (p. 6).

Romania has consistently worked to align its practices and policies with IUCN standards. However, as of 2025, most legal acts remain characterized by a mixture of half measures, multiple standards, overregulation, and incoherently blended national and international terminology, generating more environmental conflicts rather than alleviating them [14]. The overlap of protected area types and the development of the extensive network of Natura 200 sites has contributed to even greater governance confusion, especially when proper consultation with communities has been overlooked.

1.2. Protected Area Governance in Romania

Romania has defined a wide range of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs), including the following: scientific reserves, national parks, natural monuments, nature reserves, natural parks, Natura 2000 sites, UNESCO World Heritage sites, Man and Biosphere reserves, Ramsar sites, old growth and pristine forests, Geoparks, etc. Following the enactment of a dedicated law in 2007, the governance system initially adopted a relatively progressive approach, establishing a standardized legal framework where the main protected areas of national interest had a formal equivalence with IUCN categories Ia, II, III, IV, and V (Table 1). This framework also allowed private entities and NGOs to assume full responsibility as active protected area managers alongside state institutions. However, in practice, in 2018, approximately half of Romania’s protected areas benefited from active public or private administration, while the rest of the sites lacked any form of management, only existing under legal protection.

Table 1.

Romanian protected areas with a formal, assigned IUCN management category.

A protected area can be classified into a specific IUCN management category based on its primary management objectives. With the constant evolution of protected area types in Romania, specialists have realized that not all areas can be directly included in a unique IUCN category based on their types. Official discussions between stakeholders, NGOs, and policymakers were held in order to assign IUCN categories to individual sites, as many Natura 2000 sites can be fundamentally different in size, conservation methods, and management objectives, thus requiring specific designated categories. In an effort to broadly legalize conservation, stakeholders and policymakers nurtured complex administrative confusion. For example, the administrators of the first Geopark in Romania felt the need for legal protection of the area, so they also created an overlapping, similarly named Natural Park. Meanwhile, officials defined Geoparks as a new protected area type, even though a UNESCO Global Geopark does not rely on legal designation but rather on recognition based on certain standards. The Geopark was never utilized in Romania as a protected area type. This created an administrative burden in the Hațeg Region, where designations overlap and create confusion: the official UNESCO Global Geopark Țara Hațegului (administered by Bucharest University and recognized under UNESCO international standards) overlaps with the Dinosaur Geopark–Țara Hațegului Natural Park (administered by the Romanian state protected area agency and governed under Romanian law). Given this situation, for this study and project area, both designations will be mentioned, depending on the context.

The management of protected areas has deteriorated since 2018, when the government introduced a bill prohibiting private third parties from managing these areas, leading to an increase in unmanaged sites. Furthermore, due to Romania’s urgency in meeting EU pre- and post-membership obligations and its limited experience with participatory governance, many protected areas, particularly Natura 2000 sites, were designated without adequate community consultation. This resulted in significant mandatory restrictions on public and private properties, including rivers, forests, meadows, and pastures. While some intermittent financial compensation was provided to private forest owners, the government primarily concentrated on enforcing restrictions without developing a practical strategy for compensatory measures for other land and resource owners within protected areas.

Starting from the lived experiences of two key stakeholder groups—local residents and protected area administrators—this study aims to explore how these actors in the Southwestern Carpathians perceive, interpret, and respond to conservation regulations and sustainable development pressures. The research places particular emphasis on the psychological, social, and institutional dynamics that shape stakeholder engagement and influence the governance of protected areas in one of Europe’s most biodiverse and administratively complex regions.

In this context, the study is guided by two central research questions: (1) How do local residents perceive and make sense of living in protected areas in the Southwestern Carpathians? and (2) How do protected area administrators experience the challenges of implementing conservation policies and engaging with local communities? These questions seek to illuminate the subjective realities, values, and tensions that influence protected area governance at the local level.

2. Methodology

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) aims to understand individuals’ lived experiences by examining how they perceive and interact with specific events or processes. This approach enables researchers to explore, describe, and interpret the meanings that individuals assign to their experiences [15].

Smith [16] identifies two core theoretical underpinnings of this qualitative methodology: phenomenology and symbolic interactionism. These frameworks are grounded in the belief that humans are not passive observers of an objective reality but active participants who construct their biographical narratives, interpreting the world in ways that hold personal significance [17].

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) was developed to allow researchers to construct theoretical frameworks derived from participants’ insights, going beyond the specific verbal terminology and conceptualizations they use [18]. The primary goal of IPA is to explore individuals’ worldviews and the associated cognitions, offering an “insider” perspective on the phenomenon under investigation.

As a phenomenological approach, IPA prioritizes understanding an individual’s perception of an event over creating an objective account of the event itself. The essence of phenomenological psychology lies in examining individuals’ subjective and personal interpretations of their experiences [19].

Smith and Osborn [20] emphasize that IPA focuses on the in-depth exploration of personal experiences, examining how individuals perceive, interpret, and make sense of their lived experiences. This approach assumes that people are active participants in their world, continuously reflecting on their experiences to make sense of them [15].

IPA is especially valuable for exploring multidimensional, dynamic, contextual, subjective, and relatively new topics, where aspects such as identity, self-concept, and sense-making play a significant role [21]. Therefore, exploring life and living in protected areas from various perspectives—residents and protected area administrators—and understanding the meaning those participants give to their unique experiences requires such a complex research methodology.

2.1. Multiple-Stakeholder Research

This study aims to provide a comprehensive idiographic analysis of lived experiences using a multiple-stakeholder perspective on issues related to protected areas. This approach is especially needed to explore complex topics deeply rooted in multi-stakeholder relationships and requiring adjustments between key decisional factors.

According to Freeman and colleagues [22] (p. 26), a stakeholder is “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the realization of an organization’s purpose”. This multiple-stakeholder approach is rooted in systems theory, which seeks to understand the interdependence and interconnectedness of different types of actors within a system [23].

This approach emphasizes the importance of understanding stakeholders’ thoughts, emotions, and experiences whilst interpreting them to facilitate the development of effective communication and implementation strategies to engage targeted populations [24].

When the aim is as complex as Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 [25], gaining insight into diverse stakeholders’ perspectives offers significant advantages. It gives researchers and policymakers a deeper understanding of key populations’ beliefs, motivations, biases, and values. Such insights can uncover areas for intervention, collaboration, or conflict among various groups, highlighting potential misunderstandings or misinterpretations [25]. In the current study, the primary stakeholder groups consist of residents of the protected area and protected area administrators (Figure 1). These groups were intentionally selected because of their roles in enforcing protected area regulations or their direct experiences with the regulations’ impacts.

Figure 1.

Integrated multi-stakeholder analysis framework.

Additionally, stakeholders actively contribute to knowledge creation, fostering shared understandings and engagement by offering specific, concrete, and local expertise. Knowledge co-production also involves collaborative efforts among various stakeholders from different fields, such as researchers, business owners, and residents, who team up to produce information relevant to decision-making [26].

2.2. Project Area

The project area, known as the Southwestern Carpathians (SWC), is one of the largest regions in Europe, characterized by natural and semi-natural ecosystems. It boasts a high level of natural connectivity, rich biodiversity, geodiversity, pristine landscapes, and numerous rural communities with unique cultural values, including local tangible and intangible heritage. These expansive wilderness areas support complex natural processes on a significant scale, ensuring the continuous and sustainable provision of a wide range of ecosystem services that benefit both nature and people.

Covering over 7000 km2, the territory includes nearly 10% strictly protected natural areas, mainly characterized by ancient and untouched forests. This diverse region features ecotourism destinations, traditional communities, unique mountain landscapes, and rewilding zones for European bison. It also provides remarkable insights into the historical significance and evidence of critical events on Earth, highlighted by the distinctive values preserved at several important geo-heritage sites of international significance. The most notable values are represented by the endemic dinosaur and other vertebrate Cretaceous fossils found in the Hațeg Country UNESCO Global Geopark.

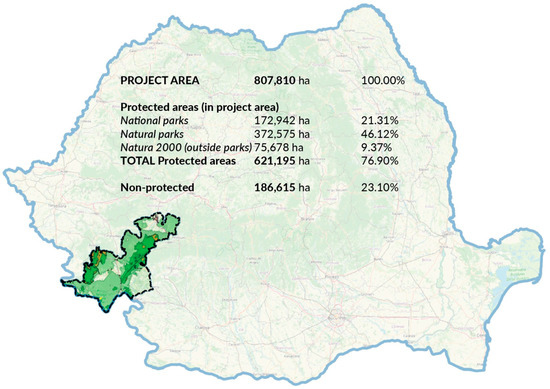

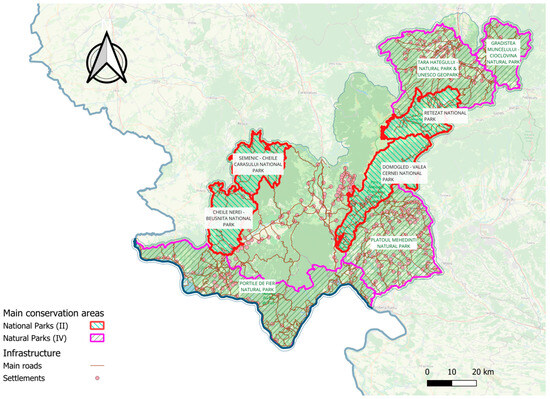

The territory includes four national parks designated as IUCN Category II (Semenic–Cheile Carașului, Cheile Nerei–Beușnița, Domogled–Valea Cernei, and Retezat), four natural parks designated as IUCN Category IV (Porțile de Fier, Mehedinți Plateau Geopark, Hațeg Dinosaur Geopark, and Grădiștea Muncelului–Cioclovina), several overlapping Natura 2000 sites, a UNESCO Man and Biosphere site currently undergoing designation, and the UNESCO International Geopark of Hațeg (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Current project area. Romania—Southwestern Carpathians.

Figure 3.

Main conservation areas. Romania—Southwestern Carpathians.

The primary administrator for the national and natural parks is the National Forestry Agency–Romsilva, supported by the Mehedinți County Council and the National Environmental Agency (formerly the Protected Area Agency). The University of Bucharest manages the Hațeg Country UNESCO Global Geopark in collaboration with local NGOs.

In terms of local conservation history, viewed through the lens of modern protected area terminology, the region includes Romania’s first national park, Retezat, established in 1935. Subsequently, several national and natural parks were created in the late 1990s. Concurrently, Natura 2000 sites were designated when Romania joined the EU in 2007, largely overlapping with existing protected areas. The Țara Hațegului Natural Park was founded in 2005, followed by the accreditation of the overlapping UNESCO Global Geopark in 2015. The management of most protected areas has often been ineffective due to limited capacity and funding, among other reasons. Certain areas face significant pressure from unsustainable forest management and illegal logging, while some pastures suffer from inadequate management or abandonment, leading to natural succession that may negatively impact species composition. Human–wildlife conflicts frequently result in economic losses for local communities, contributing to the low acceptance of wilderness, without coordinated efforts to address these issues. While natural and national park administrations typically lack the resources, legal framework, or expertise for a more community-based approach to conservation, initiatives like the UNESCO Geopark and Țara Hațegului Ecotourism Destination focus on collaborating with communities using a bottom-up approach.

2.3. Procedure

Methodologically, IPA involves an in-depth and detailed analysis of data collected from a relatively small group of participants. Often gathered through semi-structured interviews, focus groups, or reflective journals, the data are analyzed to identify patterns that are subsequently shaped into thematic structures [19,27]. Furthermore, the flexibility of semi-structured interviews enables adaptation and deeper exploration of relevant topics that emerge during the conversation. Common guiding issues and areas of interest were consistently followed to facilitate a comparative perspective analysis.

Data were gathered through three semi-structured interviews comprising 17 to 21 open-ended questions (Appendix A and Appendix B). The interview guides (one for each category—people living in protected areas, and protected area administrators) facilitate real-time, open dialogue between the researcher and the participants.

Smith [16] highlights a “natural fit” between semi-structured interviews and the objectives of qualitative analysis. These interviews provide a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of participants’ perceptions and perspectives on specific topics. They provide researchers with greater flexibility and access to insights that would be difficult to obtain through conventional quantitative questionnaires.

Aligned with the phenomenological approach, semi-structured interviews are guided by an interview framework that does not require strict adherence. The course of the interview is typically shaped more by the participant than by the guide. Researchers can explore various areas of interest related to their study, even if the questions deviate from the guide’s sequence, logic, or content. This flexibility empowers participants to steer the conversation and share what they consider most relevant and important.

Beyond gathering information, semi-structured interviews capture participants’ opinions, thoughts, and perceptions about life experiences that influenced their behavior [28], in this case, understanding attitudes toward nature, sustainable development, the local community, etc.

The data collection process spanned approximately two months, with interviews lasting between 40 and 80 min. Although most of the interviews were face-to-face, in some cases (e.g., protected area administrators), the interviews were done via Zoom or WhatsApp. While using multiple platforms allowed for greater flexibility and access to key informants, it also introduced variability in interview settings. To address this, care was taken during analysis to account for potential differences in communication dynamics, audio quality, and participant engagement across formats, ensuring consistency in data interpretation. For instance, although the interviews were both video and audio, the recording was audio-only, similar to the face-to-face recording practice, using the same device type (Tascam DR-05). Representatives of Natura 2000 Coalition Romania, the entity that implemented the project planning grant “Southwestern Carpathian Landscape: Safeguarding Europe’s Largest Wilderness Area—for the Wellbeing of Communities”, financed in October 2023 by the ELSP program, secured all necessary approvals (from the Ministry of Environment, Waters and Forests, and Romsilva) to conduct the interviews.

All interviews were audio-recorded (with participants’ consent) to facilitate transcription and subsequent analysis. All participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that their responses would remain anonymous.

2.4. Participants

According to Smith et al. [15], the number of participants in qualitative research is not fixed or “correct”. The emphasis on detailed case-by-case analysis in IPA generally leads to smaller sample sizes. Reid and colleagues [29] argue that “IPA challenges the traditional linear relationship between number of participants and value of research” (p. 22), and Hefferon and Gil-Rodriguez [30] add to this argument that “more is not always more” (p. 756).

The participants—seven residents of protected areas and three protected area administrators—formed a reasonably homogeneous purposive sample [31], sufficient to provide perspective rather than represent a population. As Smith and colleagues explain, in IPA studies, “samples are selected purposely (rather than through probability methods) because they can offer a research project insight into a particular experience” [15] (p. 48).

Furthermore, in the case of protected area residents, thematic convergence began to emerge by the sixth interview, and no substantially new insights were observed, suggesting that a point of theoretical saturation had been reached. Similar results were observed in the case of PA administrators at the third interview. This supports the adequacy of the sample size for the study’s aim: to explore how individuals interpret and navigate the tensions between conservation policies and local development. The goal was not statistical generalization, but a nuanced, in-depth understanding of lived experiences within a specific context.

The participants were purposefully selected from different local communities to ensure an optimal level of diversity in both community and socio-demographic profiles.

Participants were encouraged to share their experiences openly as residents or administrators of protected areas. During the interviews, no unexpected reactions, skepticism, or signs of exaggerated, misleading, or false statements were observed.

All interviews were intentionally selected to capture a diverse range of perspectives and experiences regarding community involvement in nature conservation and protected areas. Participants were chosen based on their potential interactions with protected area managers, conservation regulations, and resource management rather than their known support or opposition to protected areas. The popularity and awareness of protected areas in the region grew gradually, becoming especially pronounced after Romania acceded to the EU and the establishment of park administrations.

2.5. Data Analysis

The interviews were audio-recorded, and verbatim transcripts were the primary data for analysis. The analytical process closely followed Smith and Osborn’s four-stage framework [31]. This began with a detailed interpretative reading of the first interview transcript, during which initial impressions and observations were recorded in one margin. These initial notes were then distilled into emergent themes, representing a higher level of abstraction, and documented in the opposite margin [31].

Next, the researcher analyzed the themes further to identify connections, creating a table of superordinate themes for the first case. This process was systematically repeated for each of the following cases. In the final stage, patterns across the cases were identified and integrated into a master table of superordinate themes for each type of participant (Table 2). This was then developed into a narrative account, with the analysis supported by verbatim extracts from individual participants’ accounts. Smith and Osborn [32] stress the importance of idiographic inquiry, wherein each case is meticulously examined as a distinct entity before moving toward broader generalizations [21,33].

Table 2.

Emergent themes.

Furthermore, as recommended by Smith [34], an independent researcher reviewed and audited the themes to ensure the rigor of the analysis, confirming that they were grounded in the transcripts and adequately supported by examples from the data.

3. Results

The findings derived from the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) of interviews conducted with protected area administrators and residents are based on Smith and Osborn’s [31] four-stage framework, ensuring a systematic and in-depth interpretation of the data. Emerging themes were identified through an idiographic approach, where each case was examined individually before drawing cross-case connections. Key themes reflect the complex relationship between local communities and conservation policies. These themes are presented, supported by verbatim extracts, to provide a nuanced understanding of the perspectives held by different stakeholder groups.

3.1. Residents of Protected Areas

Residents’ perspectives provide valuable insights into the everyday realities of living in or near protected areas. Their experiences reflect the direct impact of conservation policies on their livelihoods, land use, and community development. Many have lived in these areas for generations, forming deep connections with the landscape and its resources. The analysis highlights key themes related to perceptions of environmental restrictions, economic opportunities, and the challenges of sustainable development. The findings illustrate both the benefits and challenges of conservation efforts from the perspective of those who call these areas home.

3.1.1. Personal and Community Relationship with Nature

The participants expressed deep admiration for the beauty of natural landscapes, seeing them as a source of inspiration and inner peace. For V., nature is more than just an aesthetic treasure—it is an integral part of his identity, shaping his daily life. In this context, he emphasizes the urgent need for stronger environmental protection, warning against the harmful impact of human activities, such as over-tourism and deforestation, which can significantly disrupt the natural balance.

“I believe that nature should be conserved as well as possible, and everyone should have a good relationship and be grateful towards nature, so to speak. In other words, we should try not to destroy or harm it as much as we can”(V)

Likewise, L. expresses great pride in the Hațeg region, which he describes as “pleasing to the eye”, with huge tourism potential. L. considers living in a protected area a privilege and actively promotes the region’s beauty. His relationship with nature is defined by tranquility, relaxation, and spiritual rejuvenation, strengthening his attachment to the area.

“There are many areas here in Țara Hațegului that are pleasing to the eye and invite you to return to those places. Since I was a child, I have lived close to nature. I was fortunate to have people in my family who loved nature. And I was taken outdoors from a young age. I live in harmony with nature. That’s how I was taught. I love nature. I love walking a lot. And as long as I can, I will keep walking”(L)

T. shares a similar perspective, highlighting nature’s generosity in Țara Hațegului and the reciprocal relationship between humans and the environment:

“I believe that nature, as I said from the beginning, has been very generous with us here in Țara Hațegului. If you respect it, it gives you so much in return—peace, relaxation, the joy of seeing its beauty, and the joy it brings to the soul”(T)

Similarly, C. sees nature as an integral part of his life, describing protected areas as his “home”. Activities such as hiking and foraging for wild plants and mushrooms strengthen his bond with an “unspoiled” and authentic environment. His words reflect a deep-seated symbiosis between humans and nature, where respect for the environment is a core value.

“I really love nature; I walk on the hills, I enjoy foraging for wild edible plants and mushrooms, and I like going into the mountains and hiking on trails. I enjoy seeing nature that is either untouched or only slightly altered by humans, and in this area, you can truly find that”(C)

M. expresses a strong emotional connection to Moceriș, the village of his birth, which he considers irreplaceable. The mountainous landscapes, gentle wildlife, and the presence of deer, wild boars, and stags define his sense of belonging.

“Well, I was born here in Moceriș. So, I wouldn’t trade this place for any other. I really wouldn’t trade it for any other place. It seems to me there are no places more beautiful than here”(M)

3.1.2. Impact of Protected Areas on the Community

By their very nature, protected areas bring both benefits and challenges to local communities. Participants highlight that these areas significantly boost the local economy by attracting tourists and investments. The influx of visitors supports local businesses and stimulates economic growth, positioning protected areas as valuable assets. However, this economic potential is often overshadowed by conflicts stemming from strict regulations. Many residents perceive these restrictions as burdensome, particularly when they limit traditional activities or require permits for even minor repairs. Frustration is further amplified by bureaucratic hurdles that seem disconnected from local traditions and community needs.

“It’s difficult because I don’t think they really understand what a protected area “entails” and don’t realize that it works in their favor, not against them. They only see the restrictions and permits, not the benefits that the protected area provides”(C)

V. considers that protected areas play an important role in the education of people living in those specific areas, serving as “learning laboratories” for both locals and visitors. They offer a huge opportunity for a better understanding of what environmental conservation means, of the importance and the role of PAs, although he perceives a discrepancy between the perceived and experienced benefits:

“Some people don’t like the fact that others come and say this is a protected area, and there’s always that territorial feeling: Hey, you don’t tell me what to do; I’ve been here before you! I had land there; you’re not allowed! Or anyway, I’ll do it my way, say what they want, and do what you want. That’s how it was at the beginning, but the impact has been positive overall because protected areas continue to help educate people. Whether you like it or not, they’re real outdoor learning laboratories”(V)

Similarly, M. noticed that most of the residents fail to understand and value the advantages offered by environmental protection, their attention being grabbed more by the immediate impact of restrictions than by some real benefits like sustainable tourism. M. mentioned that one important role of protected areas is related to the prevention of chaotic development and maintaining a fragile equilibrium between human activities and nature.

“I believe it’s for the better, although I’m convinced not everyone in the community understands this. There are certainly people who try to focus on that one negative aspect they think might affect, let’s say, their small businesses. In the short term, perhaps, but in the long term, for the community as a whole, I think it’s only for the better”(M)

On the other hand, tensions surrounding the regulations of the national park are evident. Some property owners complain about severe limitations on the use of their land, such as bans on cutting wood or clearing pastures. These rules are perceived as violations of property rights and obstacles to the free use of resources.

“The National Park is both good and not good for us. Let me give you an example. I have a plot of about 14 hectares. I bought it, and it wasn’t maintained by the people I bought it from. And now I’m not allowed to … to cut the wood that’s on it”(T)

While protected areas provide some benefits, such as tax exemptions for specific lands, these advantages are often perceived as insufficient or unevenly distributed. Therefore, some tensions might arise between the foreseen positive ecological impact and the economic challenges faced by residents. This underscores the need for improved communication and a more balanced approach that considers both environmental conservation and the economic well-being of local communities.

3.1.3. Role of Education and Public Awareness

The responses underscore the importance of public education in promoting responsible behavior in nature and fostering sustainable tourism. Raising awareness through well-structured training campaigns, which clearly outline the rules for visiting and conserving protected areas, is seen as essential. Therefore, as mentioned by C., a major concern highlighted is the lack of environmental education among tourists, which negatively affects both the ecosystem and people’s relationship with nature.

“I think what’s missing is for those who work for nature to come closer to the people, to visit the villages, to communicate better and in a way that resonates with them—not using sophisticated language or terms that the locals don’t understand”(C)

Moreover, the responses emphasize the role of ecological education in developing a sense of responsibility toward nature. V. advocates for targeted educational programs, particularly for children, to instill awareness and respect for the environment from an early age, thereby fostering a long-term commitment to conservation.

“The presence of volunteers, besides directly participating in activities and carrying out tasks for the benefit of both the community and the protected areas, also educates at home. Because when a child comes and explains what they did today and with what purpose, it’s somewhat impactful and has a very positive effect on adults”(V)

The importance of shifting public attitudes toward conservation through education is another key theme. Raising awareness about the significance and regulations of protected areas is regarded as a crucial step in fostering a harmonious relationship between local communities and nature. Targeted educational campaigns aimed at young people and tourists are particularly emphasized as a means of promoting respect and responsibility.

“I believe that everything starts with awareness, and here I think a lot of work needs to be done to make the residents of Țara Hațegului aware that they live in a protected area. From this point on, each person should find their own methods of protecting it”(T)

Additionally, the need for clearer and more accessible information for residents living in protected areas is highlighted. Many locals struggle to distinguish between different protected designations, such as the Dinosaur Geopark and the UNESCO International Geopark, leading to confusion about regulations and restrictions. One respondent (T.) suggests that enhancing public understanding could improve relationships between communities and protected area administrators.

“I knew very well that there is a difference between the UNESCO Global Geopark Țara Hațegului and the Dinosaur Geopark-Țara Hațegului Natural Park, which has a similar name. From this somewhat overlapping of terms, confusion and lack of knowledge arose in the minds of the residents of Țara Hațegului. They didn’t understand that a specific protected area imposes certain restrictions, like, for example, the construction of even the smallest building or something like that”(T)

To bridge this gap, the respondent recommends implementing educational initiatives, providing diverse sources of information, and clarifying the role of protected areas. Similarly, M. highlights the necessity of effectively communicating that conservation efforts do not restrict residents’ rights but can yield long-term benefits. This message should be reinforced by both local authorities and protected area administrators to foster a more constructive and cooperative relationship between people and nature.

“An intensive campaign should be carried out through various organizations, in schools, in pensioners’ associations, women’s organizations, to show and highlight to the residents what a protected area truly means. It should emphasize that it does not bring limitations to their rights as residents of the area and that, in the long run, it can only bring benefits”(M)

3.1.4. Tourism Management and Environmental Risks

Tourism development in the Hațeg region presents both economic opportunities and significant challenges. While the rise of guesthouses and tourism-related businesses contributes to the local economy, inadequate management of visitor influx has led to environmental degradation and a reduced quality of experience for tourists. Issues such as unregulated tourism, a lack of clear informational signage, and an insufficient number of rangers highlight the need for a more structured approach and stronger involvement from protected area administrators.

Respondents express concern over the impact of uncontrolled tourism on natural resources, emphasizing the importance of educating visitors on responsible mountain tourism. Without proper supervision, landscapes and biodiversity are at risk, prompting suggestions for the introduction of permanent guides in key mountain areas to ensure compliance with ecological norms. This highlights the necessity of adopting a sustainable tourism model that preserves the environment while enhancing visitor experiences.

“Since protected areas have become more present and people have become aware of this, all kinds of investors are coming. I believe that the people who live here are not taking full advantage of it and are not giving back to the protected areas as they should, nor are they benefiting from their presence. And I think that in a few years, there will be a very large tourism boom”(T)

Returning to the region, participant T. observed a surge in tourism activity, which they view as a long-term economic advantage, though not without its difficulties. The rapid growth of tourism brings economic opportunities but also underscores the need to balance development with environmental protection. As Hațeg is positioned as an ecotourism destination, its future tourism strategy must adhere to sustainability principles. Respondents stress the need for improved infrastructure, such as better access roads and visitor facilities, to support sustainable tourism while maintaining the integrity of the protected areas.

“I would like, and many others from the area would as well, for arrangements to be made and access points for tourism to be created. We have a very beautiful, very pleasant area. However, in a way, the National Park wants to keep things as they were, with nature, without creating trails or access roads. But, without roads, people don’t come. Because now, people have become more comfortable. They want to drive from one place to another, they don’t walk as much anymore”(M)

A key concern raised in the interviews is the impact of “chaotic” tourism, including the uncontrolled use of ATVs and the disruption of traditional village aesthetics and natural landscapes. C., for example, highlights how excessive commercialization and poorly regulated tourism projects funded through European grants risk altering the region’s cultural identity and ecological balance.

“I am concerned about over-tourism or, rather, chaotic tourism. Everyone tries to attract tourists with a brighter, shinier sign or a more colorful house, and this can harm the villages here, the local architecture, and ultimately the landscape and nature in general. The European funds that are given, even in protected areas, for ATVs and activities that are not suitable either for the protected area or, in general, for our country”(C)

Moreover, the ongoing debate between locals advocating for tourism development and the national park administrations’ focus on strict conservation illustrates the complexities of managing protected areas. While residents call for increased infrastructure investment to attract more visitors, park administrators prioritize maintaining the area’s pristine natural state. This dynamic reflects the broader conflict between economic development and environmental protection—both of which are critical to the region’s long-term sustainability.

“Tourism should be centralized. These are sustainable things for both the community and the visitors of the protected areas. Because it is chaotic and local. Just like all over Romania and in Țara Hațegului. Also, there should be better preparation of the sites. For example, paleontological sites, geological sites”(V)

Overall, the findings emphasize the urgent need for a more coordinated tourism strategy that balances ecological preservation with economic growth, ensuring that Hațeg remains both a thriving community and a well-protected natural heritage site.

3.1.5. Relationships with Local Authorities and Political Influences

The relationship among local communities, authorities, and protected area administrators is characterized by a complex interplay of power, policy, and local economic realities. Residents share a deep connection to their land and traditional ways of life but feel constrained by regulations that limit their autonomy. The recurring frustration with land use restrictions indicates a lack of effective communication between conservation authorities and landowners, resulting in resistance rather than cooperation.

For instance, M. expresses his frustration related to the regulation of PAs that limit his ability to manage his land as he wishes:

“I am the owner, and others are using it in some way. So, I am the owner, yet I cannot maintain it as I want. If I am the owner, then I have the right to maintain it. Why do others impose restrictions on me not to …?”(M)

One participant (M) perceives these restrictions as an infringement on property rights, emphasizing a recurring issue in conservation areas where land use regulations conflict with local economic needs and traditional practices.

On one hand, local authorities are perceived by some participants as overwhelmed by basic infrastructure and community needs, and therefore less able to pay attention to issues related to nature conservation. One interviewee noted that authorities tend to prioritize essential infrastructure, such as roads and bridges, and do not appear to allocate time or resources toward engaging communities about protected areas. This view reflects a specific perspective and should not be interpreted as a universal condition across all municipalities.

“I think local authorities are still struggling to build roads and bridges, and they are quite advanced in completing these very basic infrastructure projects in the villages. I don’t see them having the time to communicate or take real-time action regarding protected areas”(C)

On the other hand, other locals (V.) believe that the national parks and the political environment impose restrictions without providing viable alternatives for daily living. At the same time, the town hall is seen as a passive institution, incapable of effectively addressing the real issues of the community.

“For several years now, this road, although supposedly planned, has not been built. The mayor keeps saying that it’s because of the park, because of environmental reasons, and as a result, the road is not being constructed”(V)

Furthermore, the findings suggest that local authorities do not have adequate knowledge of the protected areas in the region and, consequently, are unable to provide support to residents in understanding and complying with the imposed regulations. This was mentioned by T.:

“Local authorities should undoubtedly be the first to know that there are protected areas within their administrative-territorial unit, what type of protected areas these are, and, when a resident approaches the local public authority for a permit or any other matter related to the area, they should be able to explain what that protected area entails. However, I repeat, this can only be done if those responsible within the local public authority have a thorough understanding of the protected areas within their jurisdiction, what they represent, and what restrictions might be imposed there”(T)

Similarly, V. draws attention to the passivity of local authorities in managing protected areas. Although an institutional framework exists, the actual involvement of local administrations is minimal, leading to difficulties in both the development and conservation of these areas.

“I think the authorities should be a bit more involved. In general, not just in protected areas, but obviously, there is also a need for greater involvement from local authorities here because there are many things that would help. For example, facilitating developments in protected areas and facilitating the conservation of protected areas should largely be the responsibility of local authorities”(V)

Moreover, the attitude of local authorities is seen as inconsistent—while some town halls are proactive and seek to support the region’s development, others are criticized for their lack of involvement, leading to the stagnation of essential projects, such as improving access to important tourist areas. This imbalance creates frustration among locals, who perceive a lack of a unified development strategy and a real dialogue between authorities and the community.

3.1.6. Challenges and Opportunities for Sustainable Development

Participants voiced concerns about the potential risks associated with tourism investments, particularly the exploitation of natural resources and the selling of land at low prices to external investors. This trend, they warn, could significantly alter the fabric of local communities, raising the cost of living and disrupting the region’s socio-economic balance.

T. highlights the need for appropriate infrastructure to support ecotourism, emphasizing that improved roads and designated bike trails are essential for facilitating responsible visitor access. He believes such measures would allow for sustainable tourism development, enabling visitors to explore the region without harming its natural environment.

“The fact that cycling routes have been developed, that thematic trails have been created, and that work is being done in the field of sustainable development is a good thing. Now, I believe these things need to be maintained in the future”(T)

Moreover, T. underscores the critical role of local authorities and national agencies, such as the National Agency for Protected Natural Areas (ANANP), in preserving both natural and cultural heritage. However, he stresses the need for more active engagement and stronger collaboration between specialized institutions and local administrations to ensure that conservation efforts align with modernization.

“It must be done in full harmony with nature and by respecting these protected areas. I don’t know if this has been done or if serious steps have been taken in this direction so far, but I believe that people are starting to understand, and we hope it’s going in the right direction. […] The only benefits and the only viable path I see for Hațeg at the moment are to exploit its natural and historical benefits”(T)

C. takes a broader perspective, arguing that sustainable development should blend modernization with respect for the region’s natural and cultural identity. Drawing inspiration from countries like Germany, he advocates for development strategies that integrate modern infrastructure while preserving the character of the landscape and local traditions. This approach, he suggests, requires a combination of education, community engagement, and gradual economic growth rooted in sustainability.

“I’m thinking of harmonious and gradual development with nature. The first things I would consider, without destroying what we have, but at the same time preserving local values and ensuring comfort, without compromising comfort. […] More funds should be allocated to protected areas, somehow for businesses that can develop in protected areas—not for ATV rentals, cars, or other harmful activities, but for local businesses that can grow here. Tourism-related businesses, crafts, and of course, modernized gastronomy”(C)

Similarly, M. emphasizes the importance of balanced development that prioritizes collaboration among locals, authorities, and investors. He highlights the need to maintain the region’s natural and cultural values while also ensuring that residents have access to modern infrastructure and basic comforts. He sees this as key to integrating environmental protection with economic progress.

“Many times, we tend to say that people in the village should live in the same straw and wood houses, and why do they need sewage, water, and all the things that we ultimately benefit from in the city? […] One form of development would be if the park and roads are properly arranged, but there should be access roads to certain places. For example, the waterfall on Valea Satului or the Devil’s Lake. More hikers and tourists would come. And through this, the local people would benefit as well, as they could sell more of their products and become more known”(M)

Across all discussions, participants emphasize that sustainable development is crucial for the region’s future. It involves job creation, infrastructure improvements, and environmental conservation. However, V. warns that irresponsible tourist behavior, such as littering, could severely impact the fragile natural balance of the area.

“There should be no more destruction of potential paleontological sites. Tourism should be centralized. These are sustainable things for both the community and the visitors of the protected areas”(V)

To address these challenges, he calls for active involvement from local authorities, urging them to collaborate with environmental institutions and communities. Clear regulations and ecological education initiatives must be enforced to ensure that economic growth does not come at the cost of environmental degradation.

Balancing modernization with nature conservation is key to achieving sustainable development. While tourism investments have the potential to generate substantial benefits, they require careful planning, inter-institutional cooperation, and active community participation. A long-term sustainable strategy, rooted in education and respect for local heritage, is essential to securing the region’s prosperity.

“I believe that, as a conclusion, this is how I see it, as a resident of this area and, again, as someone somewhat involved in tourism activities, that a truly sustainable development and an increase in the prosperity of the residents in the long term involves maintaining these protected areas. And not only that but also a serious campaign to inform the residents of the area. Because, with a serious informational campaign, they will understand and perceive that they live in an area that is not only protected and brings them restrictions, but that it can also bring them future benefits”(T)

3.2. Administrators of Protected Areas

Protected area administrators are directly responsible for implementing conservation policies and managing natural resources within designated sites. Their perspectives offer a unique understanding of the challenges associated with enforcing regulations, engaging with local communities, and addressing conflicts over land use. The analysis identifies key themes such as conservation enforcement, stakeholder collaboration, and the broader implications for sustainable development. These findings provide an in-depth look at the administrative and ecological responsibilities that shape decision-making in protected area management.

3.2.1. The Management and Complexity of Protected Area Administration

The management of a natural park is complex due to the necessity of balancing environmental conservation with the needs of local communities. Unlike national parks, where restrictions are clearer, natural parks must integrate human activities with conservation efforts.

For example, as reported by J., the management of the Iron Gates Natural Park is multifaceted, involving collaboration with various institutions, ensuring biodiversity protection, enforcing regulations, and engaging with local communities. The administrative team faces logistical and regulatory challenges while striving to maintain a balance between conservation and economic activities.

“The management of a protected area is specific and unique to each natural or national park. It is not the same everywhere. Many problems arise from this. For example, when we analyze urban planning projects, the general urban plans (PUGs) often contradict the regulations of a protected area”(J)

The administration of a natural park requires specialized knowledge and a nuanced approach to balancing environmental conservation with local development needs. The complexity of this role is exacerbated by overlapping responsibilities and the need for constant negotiation with various stakeholders. As stated by N., managing a natural park requires continuous dialogue and compromise:

“In a national park, the restrictions are clear, more activities are forbidden. In a natural park, there are permanent communities, and you have to consider both their needs and nature conservation” (N); “The biggest challenge is addressing the needs of the local population, especially regarding firewood. People were used to taking wood from their lands, but now they are restricted. Initially, they blamed the park administration, but over time, they started seeing the benefits of being in a protected area”(N)

Many issues stem from misunderstanding regulations, and effective communication is essential for acceptance. Illegal constructions and resource access disputes remain key challenges.

“Illegal constructions have become a major issue, with people exploiting legal loopholes to build in areas where it is not allowed”(N)

3.2.2. Conflict and Reconciliation Between the Needs of Local Communities and Nature Conservation

One of the greatest challenges in park management is striking a balance between environmental conservation and the economic aspirations of local communities, which often involve expanding residential areas, developing guesthouses, and utilizing natural resources. J. made an observation regarding Iron Gates Natural Park:

“A mayor wants to update the General Urban Plan (PUG). In their vision, they see only development areas, only residential zones, and more and more expansion, until the entire administrative-territorial unit (UAT) is occupied with houses”(J)

Tensions between local authorities and the park administration originate from the lack of long-term vision and the mayors’ tendency to prioritize territorial expansion without a sustainable strategy. The lack of legislative and financial support for local communities leads to a negative perception of national parks, which are seen as imposing restrictions rather than offering opportunities.

Furthermore, environmental protection laws impose restrictions that often conflict with the interests of local communities, especially regarding land use and economic activities. Interviewee B. highlights the resistance faced when enforcing conservation rules, as many locals believe their rights and freedoms are being limited:

“Many people own land in strictly protected areas and do not understand why they cannot build, especially when they see a guesthouse 100 m away. They feel that the protected area takes away many of their freedoms and limits their activities”(B)

This constant need to comply with environmental regulations often clashes with local expectations. Disputes over land use, firewood access, and pasture management are the most common.

“Restrictions exist, but compensations should also be provided. The issue arises when compensations are delayed or insufficient” (N); “There was resistance to understanding that some areas could not be used as they were before. However, once we explained the benefits and legal options, many people accepted the regulations” (N); “We had conflicts over illegal constructions. Some individuals deliberately ignored regulations, even after receiving negative approvals, which forced us to take legal action”(N)

A constant challenge exists between the need to protect the environment and the ambitions of local communities to develop and expand. Conservation regulations play a crucial role, but without transparent communication and fair compensation, they can lead to frustration and resistance. Legal disputes often arise, reflecting the complexities of enforcement; however, many conflicts could be avoided through proactive engagement. By fostering open dialogue and establishing clear guidelines, park administrators can lessen opposition and build stronger partnerships with local communities, creating a more balanced approach to both conservation and sustainable development.

3.2.3. Ecological Education and the Importance of Effective Communication

A central element of the interviews is the role of education in changing how local communities and tourists perceive the importance of environmental conservation. The park administrators believe that education is most effective when initiated at a young age, as children are more receptive and can become agents of change in the future.

“The most effective thing you can do is to go to preschoolers or primary school students. Because from here, they can start accumulating knowledge. Even if you organize a clean-up action or do an educational activity with ‘Alternative School Week’ and take them out, people become more sensitive this way” (N); “We are the ones who open their eyes. And we show them how tourism works, ecotourism works, how to manage the issue”(N)

Environmental education is essential for long-term mindset change. The park administration’s strategy of collaborating with schools and providing hands-on experiences in nature has proven effective, but requires greater support from local authorities.

“People don’t know. But that’s why we are here, to raise awareness. We conduct awareness activities, first in schools, then at local authorities, then with the general population”(J)

Awareness campaigns and local engagement have played a significant role in shifting attitudes toward conservation. The park administration has focused on involving communities in initiatives that highlight the benefits of environmental protection, as mentioned by B.:

“The secret to success is communication. Initially, there was resistance, but through continuous dialogue, people began to understand and even support conservation efforts” (B); “We have seen a shift in behavior regarding waste disposal. Educational initiatives and better waste management policies have reduced pollution in the area. Programs like ‘Let’s Do It Romania’ have helped change perspectives on environmental responsibility”(B)

Education and awareness are key tools for changing attitudes toward conservation. When people understand the benefits of protected areas, they are more likely to support and participate in sustainability efforts. Engaging with schools and involving children in ecological activities is a proactive way to build long-term environmental responsibility within the community.

“On Park Day, we organized activities with 13 schools, working with students to raise awareness about nature. If children understand certain things from a young age, it will be easier for them to act responsibly as adults”(J)

Investing in environmental education ensures long-term benefits by shaping future generations’ attitudes toward conservation. The emphasis on working with schools demonstrates a commitment to proactive, rather than reactive, environmental management.

3.2.4. The Economic Impact of Tourism and Conservation

A park’s presence has both economic and social implications, influencing tourism, land use, and local traditions. Tourism, particularly around the Dacian fortresses, has driven demand for accommodations and services, as observed in N.’s interview:

“The number of tourists visiting the area has increased, which has led to a growing demand for accommodations” (N); “Some communities have adapted, developing guesthouses and leveraging tourism, while others are still struggling to see the benefits” (N); “We are pleasantly surprised that people consider traditional architecture in their constructions. This is partly due to park administration’s guidance”(N)

The park supports local economic development, mainly through tourism, but it must be carefully managed to avoid threatening the environment. However, communities differ in their capacity to take advantage of these opportunities, and ongoing education is essential to fully merge conservation with economic growth, as reported by J.:

“In seven years, we have increased revenues and visitor numbers from around 2000 per year to 20,000. The problem is that if you bring too many tourists, you overload the site. So, you need to manage it carefully” (J); “I will not let it get out of control. No way. Everything must be measurable. Any site, any area, I won’t develop it excessively or make access too easy, so it suffocates the area and changes its natural state”(J)

As observed, although tourism has grown significantly and contributed to economic development, it must be managed strategically to prevent the overloading of fragile ecosystems and environmental degradation. The concept of ecotourism is actively promoted, but greater involvement from authorities and clearer regulations are needed to maintain a balance. Therefore, the park administration works to control visitor access, regulate transport, and promote eco-friendly practices.

“We have managed and controlled the situation in the ‘Cazanele Dunării’, where we have a visitable cave” (B); “Tourism has begun to be more regulated, ensuring that environmental impact is minimized”(B)

Sustainable tourism offers economic benefits while supporting conservation efforts. However, proper regulation and infrastructure development are necessary to maximize its potential without harming the ecosystem.

3.2.5. Challenges and Opportunities in Collaborating with Local Communities

One recurring issue is the lack of effective collaboration between the park administration and municipal authorities. There is a disconnect between environmental protection policies and local development plans, and partnership initiatives are rare or nonexistent.

“We need to think things through. We need to develop plans in partnership to ensure continuity in the community. The County Council does not organize meetings with key decision-makers in this county… (J); “The real issue right now is that a mayor should find a source of funding and say, ‘Mr. Director, let’s form a partnership and do this, this, and this’”(J)

The lack of continuous dialogue and a well-organized collaboration framework impedes the successful implementation of conservation and development initiatives. This ongoing gap contributes to persistent frustration as local communities face inadequate support from central authorities—both in terms of funding and fair enforcement of regulations. A more structured cooperation framework could enhance both environmental protection and the development of sustainable economic opportunities for communities.

“At present, no one has studied anything related to protected areas in school. No faculty or school teaches this” (N); “The central public authority should pay much more attention to national parks” (N); “We have to write projects to implement our measures, but if you don’t have the right people, everyone just talks”(N)

It seems that park administrators are left to handle complex problems on their own, without adequate institutional training or sufficient resources. Greater involvement from central authorities is necessary to develop coherent policies supporting protected areas and local communities.

Despite these frustrations and tensions, successful instances of collaboration exist between park administrations and local communities. These include partnerships for ecological clean-ups and sustainable tourism initiatives.

“We have managed to establish partnerships with local communities for environmental clean-up activities” (B); “Municipalities contribute by providing workers and transportation for waste collection”(B)

Building cooperative relationships with local communities enhances conservation efforts and fosters a sense of shared responsibility for protecting natural areas.

Even though the beginning was a bit harsh, over time, cooperation with local authorities has improved, as reported by B., leading to better planning and fewer conflicts. However, past tensions and litigation demonstrate the challenges of aligning development projects with conservation policies, particularly those related to economic growth and tourism infrastructure.

“Most misunderstandings have been with local councils. In one case, a municipality tried to pave a road through a protected area, arguing it was necessary for tourism, despite restrictions” (B); “In the past three years, discussions have improved significantly. Now, mayors call us before making decisions to ensure compliance with zoning laws” (B); “Joint actions, such as clean-up campaigns, have strengthened relationships between the park administration and local communities”(B)

3.2.6. Administrative Challenges and Personal Resilience

The administration of a natural park comes with significant challenges, including underfunding, difficult interactions with the public, and physical risks associated with enforcing regulations. Park rangers and administrators often face opposition from locals, sometimes putting their safety at risk. A stronger legal framework and better community relations could help address these challenges.

“The most difficult situations were when I had to issue fines. People were resistant, even with the presence of authorities” (J); “I’ve encountered hostile individuals in the forest, engaging in illegal logging or other prohibited activities”(J)

Furthermore, the enforcement of environmental laws is often met with skepticism and frustration from locals. Many perceive restrictions as unfair or arbitrary, especially when comparing their limitations to past practices or to what others are allowed to do.

“Residents in these areas do not like the restrictions because they limit access to land use, including construction.” … “Over time, they have come to understand they are in a natural park, and that hunting and land use are regulated”(B)

Therefore, perceived fairness plays a significant role in community acceptance of regulations. Transparent decision-making and consistent enforcement are key to fostering trust and compliance.

Moreover, local communities often perceive the park administration as an entity imposing restrictions rather than as a partner. Many believe that the park has taken control of their land, a misconception reinforced by misinformation.

“People were convinced that the park had taken over their land. They were wrongly indoctrinated by various sources that the park administration had control over their property” (N); “When I arrived in 2017, the perception of the natural park was very negative. In contrast, at Retezat National Park, there was a natural respect for the protected area. Here, people saw it as a burden. Over the years, we have improved this perception. Now, people see the benefits, and collaboration has increased”(N)

Misinformation, misunderstanding, and historical grievances have shaped negative perceptions of the park. A critical aspect of public misunderstanding is the distinction between natural and national parks. The interviewee quoted below clarifies these differences, particularly regarding land use, conservation restrictions, and permitted activities.

“There is a big difference between natural and national parks, mainly in terms of protection categories.” … ”A natural park is primarily established for landscape conservation, and it includes human settlements, whereas a national park has stricter protection rules and no urban areas”(B)

Clarifying these distinctions is essential to improving public perception and compliance with regulations. Many frustrations stem from a lack of understanding regarding what is and is not allowed in protected areas.

The reality is that balancing development with conservation remains a long-term challenge. Future efforts must focus on sustainable economic activities, resource management, and securing funding for conservation projects, as mentioned by PA administrators.:

“There is always work to be done to balance human needs with nature conservation. The ideal balance may never be fully achieved, but it is the goal we strive for”(J)

“Protected areas should be seen as opportunities rather than restrictions. We encourage sustainable tourism and responsible land use instead of exploitative industries”(N)

“Financing remains a challenge. Many conservation activities rely on external funding, which is not always guaranteed”(B)

It is becoming clearer and clearer that sustainable development requires continuous effort and adaptation. Ensuring various sources of financial support and fostering environmentally friendly economic activities are critical for the long-term success of conservation efforts.

4. Discussion

While it relates to individuals as experts in their own experiences and explores their personal histories articulated in their own words, with rich detail [18], Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) has certain limitations. One such limitation is that it heavily relies on participants’ ability to express their thoughts and emotions when discussing complex topics like protected areas and sustainable development. Willig [35] further supports this notion, suggesting that conveying the intricate details of lived experiences can be particularly challenging, especially for those who are not accustomed to reflective and detailed self-expression. This challenge is especially pertinent in the context of this study, as many residents from the rural areas under investigation may exhibit lower levels of reflexivity [36] or lack the discursive tools necessary to convey their experiences with the depth and nuance that IPA requires. Consequently, there is a risk that certain facets of their lived experiences go underexplored or are expressed in a simplified manner, potentially limiting the richness of the data. Future research could address this limitation by incorporating additional elicitation techniques, such as visual methods or narrative approaches, to better assist participants in expressing their perspectives more comprehensively.

While Smith et al. [15] advocate for self-selecting sampling as the preferred approach in IPA studies, this method has inherent limitations. Specifically, it may lead to the overrepresentation of individuals who are more engaged, vocal, and willing to share their personal experiences. At the same time, those less inclined to participate, such as marginalized community members, may be underrepresented. Additionally, the involvement of the Natura 2000 Coalition Romania, a key stakeholder, in the recruitment process may have subtly influenced participant selection and responses, despite all measures taken to mitigate bias. Given the coalition’s established relationships with local communities and protected area administrators, these connections likely facilitated access to participants and fostered a sense of trust in the research process. However, they may also have shaped participants’ willingness to engage and how they articulated their perspectives. While this familiarity helped ensure meaningful discussions, it is possible that individuals with certain voices or viewpoints were more willing to participate in the study than others. Future research could build on this by diversifying recruitment strategies, such as incorporating additional outreach methods or engaging independent intermediaries, to further enhance the inclusivity of participant perspectives.

Furthermore, as Tuffour [37] observed, IPA has faced criticism for its ambiguities and lack of standardization [38]. Some scholars [30,39,40] argue that it is primarily descriptive and insufficiently interpretative, focusing heavily on thematic mapping while providing limited critical engagement with structural or action-driven dimensions of lived experience. Given this study’s focus, the descriptive nature of IPA, while valuable for capturing individual perspectives, may be inadequate in addressing pathways for change and community engagement in sustainable development.

A promising direction for future research is the adoption of Participatory Action Research (PAR), which integrates inquiry with concrete, community-driven action [41]. Unlike IPA, which primarily emphasizes understanding lived experiences, PAR actively involves stakeholders in co-constructing solutions to the challenges they face. This methodological shift could provide deeper insights into how residents and protected area administrators can collaboratively negotiate restrictions, develop sustainable practices, and enhance local buy-in for conservation measures. By engaging stakeholders not only as participants but also as co-researchers, PAR could foster more inclusive and pragmatic approaches to sustainable development, ensuring that solutions are contextually relevant and socially accepted.