Abstract

This study investigates the effect of Ethiopian economic liberalization policy and manufacturing firms’ international competitive priorities on the export performance after economic reforms in 1991. This study also aims to clarify how these economic reforms and the firm’s competitive priorities affect the international market export performance. This study further examines and identifies the most important variables that significantly affect export performance in relation to economic liberalization and the firm’s competitiveness. To achieve these objectives, both primary and secondary data were collected. A cross-sectional survey was conducted from 114 fully privatized manufacturing firms, utilizing a structured questionnaire with five Likert-scale items. The findings of this research indicate that law and order (LaO) and government intervention, incentive schemes, and trade openness have a significant relationship with the export performance of exporting firms in Ethiopia. This study also infers that firms must incorporate firm’s international competitive priorities’ cost, flexibility, and product quality as part of their competitive strategy. These competitive priority metrics limit export performance in terms of both subjective (e.g., export satisfaction) and quantitative (market share, profit) factors. This study concludes that economic liberalization and competitive priority measures are positive and have a significant relationship with the export performance of manufacturing firms in Ethiopia after 1991 reforms. The result also provides valuable insights for manufacturing firms and policymakers, highlighting the importance of economic liberalization in enhancing the export capabilities of privatized firms. These insights can guide the development of effective strategies to boost exports and foster sustainable economic growth.

1. Introduction

Since the implementation of economic liberalization initiatives in 1991, Ethiopia has made significant strides in encouraging private investment and transitioning state-owned enterprises into privatized entities. According to economic scholars, this period is considered as a turning point for the Ethiopian political economy. Before 1991, protectionism demarcated Ethiopia’s economic strategies under both the Imperial and Derg governments, which limited the efficacy of private enterprises and promoted socialized economic activities [1]. The restrictive policies aimed at safeguarding domestic firms inadvertently led to the creation of inefficient state-owned enterprises reliant on government support [2]. After the reform period, the national economy has noted a positive and incremental trend until 2018/19 [3]. There are many indicators that recognize that the Ethiopian economy has improved significantly in all areas of economic indicators since the country’s economic and political reforms in 1991. In 1991, the government implemented macroeconomic transformations, including the privatization of inefficient governmental firms. These shifts were intended to enhance operational and marketing efficiency for enterprises both domestically and internationally [4]. Ethiopian manufacturing firms’ export performance might be significantly influenced by the economic reforms implemented since 1991. The government’s initiatives to enhance business infrastructures, reduce trade obstacles, and combine robust regulatory frameworks are examples of policy measures that generally seek to improve the business climate as a whole. Adjustments made after the reform era may affect a manufacturing firm’s capacity to compete on the global market [5].

The link between economic liberalization and the export performance of manufacturing firms is increasingly relevant as Ethiopia continues to route its post-reform landscape. According to the National Bank of Ethiopia (2020/21), the country’s economic situation has improved absolutely since the reforms. The period following 1991 marked a critical juncture in Ethiopia’s political economy, leading to substantial macroeconomic reforms, including the privatization of state-owned enterprises. This transformation contributed to a consistent growth trend, with the economy recording a growth rate of 9% in 2018/19, despite a decline from prior double-digit figures (National Bank of Ethiopia, 2019/20). The Ethiopian government continues to target industrial growth and export-led strategies while simultaneously modernizing the agricultural sector, which has traditionally dominated the economy [2].

Recently, after 2018, the transition in governance from the EPRDF to the Prosperity Party (PPP) has ushered in policy continuations aimed at bolstering economic growth and improving the competitiveness of the manufacturing sector in international markets.

Despite these macroeconomic adjustments, the challenges posed by globalization continue to complicate Ethiopia’s quest for competitiveness in the international market. International constricted competitions have transformed the business landscape, introducing new pressures and opportunities for firms, including changes in consumer demand, international business expansion, and economic integration [6,7]. To compete effectively and efficiently in global markets, Ethiopian manufacturing firms must harmonize their domestic efforts with international business dynamics, particularly regarding their export strategies.

Although the Ethiopian government has undertaken significant economic reform incentives in the private sector over the past two decades, the manufacturing sector remains quite underdeveloped and infant. The current literature predominantly focuses on the broader impacts of liberalization on economic growth but often overlooks the specific dynamics of how these reforms affect the export capacities of privatized firms. Prior research has highlighted the relationship between economic policies in general and manufacturing performance in developing countries, but there is a prominent gap in understanding how the specific factors of privatization policy influencing the export performance of Ethiopian manufacturing firms post-liberalization.

Thus, this study planned to fill that research gap by systematically exploring the association between economic liberalization policies and the export performance of Ethiopian privatized manufacturing firms. By analyzing the interdependencies of various factors, including law and order, trade openness, and incentive schemes, this research seeks to provide actionable insights for policymakers and business leaders. The results of this study are anticipated to contribute to Ethiopia’s broader economic objectives, including the formulation of effective corporate strategies and the development of policies that promote sustainable export growth and economic stability. By addressing this knowledge gap, this research will enhance our understanding of how targeted economic reforms can enable firms to navigate the complexities of international markets while driving national economic growth.

2. Literature Review

The main economic growth drivers, especially for developing countries, are exports, which give foreign exchange earnings and advance economically [8]. Classical and neo-classical economists were the first to propose that trade may spur economic growth [9]. Export growth results in improved resource distribution and allocation, capital formation, employment creation, economies of scale, and production efficiency [10]. According to [11], it was again argued that exports of goods and services are among the most significant sources of foreign exchange and reduce pressure on the balance of payments and generate job possibilities. The international market is most dominantly an attractive and vibrant business environment. It consists of diversified multinational (international) firms with the bulk of competing products and services, which create significant competitions. International marketing creates a plethora of business opportunities for both developed and developing countries [12]. The export performances of firms have been affected by different controllable and uncontrollable variables. These variables become complex and multifaceted when considering international marketing. Government policies, industry-specific characteristics, and market features from both the home and the host nation are diversified [13]. Ethiopia plans to obtain the fruit of international marketing by incorporating various policy shifts and amendments at different times. The 1991 economic liberalization program was the most significant and pervasive policy change in Ethiopian history, and it had a ripple effect on the country’s macroeconomic structure as a whole.

According to [8], exports would be the main concern of a nation for the development of the national economy [14]. Effectiveness, efficiency, and adaptability are the three primary elements of export performance, which is viewed as a complex, multifaceted phenomenon [13,15]. Both objective metrics, like sales, profitability, or marketing metrics, as well as subjective metrics, such as customer satisfaction, can be used to characterize export performance [16].

The manufacturing sector in Ethiopia is structured and performs similarly to the rest of sub-Saharan Africa [17]. Two characteristics of Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector stand out: first, “a low level of industrialization”, as measured by the sector’s competitiveness, export revenue, industrial intensity, and GDP share. Second, small businesses and resource-based industries, especially the food industry, dominate the industrial structure, which is centered in the capital city [5].

Ethiopia has a very tiny and infant export industry. Less than 10% of the nation’s GDP is derived from exports of goods and services, which is much less than the 24% that is expected given its degree of development. Ethiopia’s export performance has suffered recently, as exports of both products and services as a percentage of GDP have stalled. The main causes of Ethiopian businesses’ subpar export performance are that, first, compared to comparator countries, Ethiopia exports fewer goods and has less access to foreign markets. Out of the 4750 total items in the classification used in 2016, Ethiopia exported 231 different products, compared to 708 products exported by Kenya, 756 by Bangladesh, 2802 by Vietnam, and 3106 by Malaysia [18].

In the same manner, the majority of Ethiopia’s exports are still made up of primary goods (oilseeds and coffee make up about half of the total exports), with the proportion of manufactured goods like clothing and textiles having barely increased. Compared to comparative countries, even present exports are sold in fewer markets. While Kenya has 96 export markets, Bangladesh 118, Vietnam 136, and Malaysia 137, Ethiopia exports to 78 nations. Thirdly, Ethiopia is currently only capturing 1.43 percent of the international market potential for the products that it exports; this is a decrease from 2.05 percent in 2017 [18].

All of these factors led the Ethiopian government to sectorial reforms in all perspectives. They were considered as a driving force behind the Ethiopian economic liberalization reforms, which is important for resource allocation, increasing international competition, and increasing inflows of investment and capital accumulation [12,19]. Reduction barriers of trade facilitate the potential of imports and exports, as well as capital inflows, outflows, and domestic investment, to increase the productivity of businesses that increasingly rely on competitive, modern services as inputs, which are all important factors in growth and competitiveness today [20]. As explained by [12], the major goals of the Ethiopian government in implementing liberalization were aimed at macroeconomic stability and rapid and sustainable economic growth. Tariffs have been reduced, licensing bureaucracy has been reducing [20,21], and trade liberalization and economic growth are inversely related in developing countries, specifically in Africa.

Economic liberalization can usually lead to increased domestic sector efficiency depending on (i) the level and extent of the initial protection in a given sector; (ii) the degree of openness in a given sector, that is, whether the sector is export-oriented; and (iii) the capacity of a given sector to compete against imports and their incentives. Export-oriented industrial sectors are anticipated to benefit the most from trade liberalization measures [22,23]. In this era of intense international competition, a firm’s ownership structure has a big impact on how well it exports. The reason why public-owned companies consistently struggle with performance in the international market is because their incentive plans are inadequate and give managers a large amount of latitude to follow their own agendas rather than concentrate on their assigned responsibilities [24]. However, despite the government’s efforts to liberalize the economy over the past 20–25 years in Ethiopia, the manufacturing sector remains in its infancy. Typically, to improve the understanding of the connection between economic reforms and export capacities in the context of developing nations, research has been conducted on the relationship between the realm of economic liberalization policy and the export performance of privatized manufacturing enterprises in Ethiopia.

Liberalization of the economy alone is not sufficient to competitive in the international market unless the firms are competent enough for global completion. Competitiveness is a key factor to consider in most strategic marketing studies. It can be measured at national, industrial, and firm levels. Nations can compete only if their enterprises can compete; in international markets, firms, not nations, can compete [25]. Competitive advantage refers to the circumstances or capabilities that allow a corporation to outperform its competitors [26]. Thus, to achieve a competitive advantage, firms should also consider their own external position and internal capability [27]. Firms’ qualities and actions account for 36% of the difference in profitability [28]. Other pro-firm views [29,30] focus on individual firms and their strategies for global operations and resource positions to identify the real sources of their competitiveness. Understanding the industry structure is also critical to good strategic positioning, as it defends against and influences competitive dynamics in a company’s advantage [31].

The number of multinational businesses (MNEs) in emerging world regions accounts for the majority of growth [32,33]. These new players have introduced new business models [34,35,36]. These new forms of global competition continually change the rules of the game and call for more agile and aggressive competitive moves [37,38]. Accordingly, to effectively compete, companies must develop tactics and strategies [31,33]. Broadly, companies must shift from competing for endowments or comparative advantages (low-cost labor or natural resources) to competing for competitive advantages arising from superior or distinctive products and processes [39].

The firm’s competitive advantage includes factors or capabilities that enable a company to show a better performance than competitors [26]. Thus, to achieve a competitive advantage, an organization should also consider its own external position and internal capability [27]. Concerning the dimension of competitive priorities (cost, flexibility, or quality), there is broad agreement that they can be expressed in terms of some basic components: cost, quality, and flexibility are the most common competitive priority measures [40,41,42]. Institutional theories have been used as bases “as strong legal frameworks reduces risk of business and transaction cost and fostering competitiveness”. Furthermore, resource-based views (RBVs), clarified as incentive programs, provide firms with financial, technological, etc., resources to improve international firms’ capabilities.

Furthermore, industrial organization (IO) recognizes the impact of the external environment on the export performance of a firm. This perspective’s main claim is that external factors, including an industry’s structural features, determine the strategies that businesses can use, which, in turn, affects how competitively these businesses can operate [43,44]. With the combination of all theoretical bases, the researchers develop a conceptual relationship between variables. The exporting market ideally boosts economic growth in a variety of ways. It fosters connections between production and demand, generates economies of scale through expanded global markets, boosts efficiency, promotes the adoption of advanced technologies found in capital goods produced abroad, improves human resources and learning effects, boosts productivity through specialization, and attracts foreign direct investment [14]. The argument that carefully managed trade openness is a strategy for achieving rapid growth has been supported by the growth of newly industrialized countries (like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand) and the four tigers (Hong Kong, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan) [14].

3. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework for this study is designed to delineate the connections and interactions among various elements influencing the export performance of privatized manufacturing enterprises in Ethiopia, particularly within the context of economic liberalization policies. A firm’s effective strategic response to external environments leads to a greater export performance [45]. From a free market power perspective, alliances offer a way to reduce the uncertainty brought about by internationalization and lessen competitiveness [46,47]. Firms can obtain a competitive position in their market by gaining more market power through the firm’s integration. The firm’s integration is also functional and effective through a supportive policy framework and encouraging easy doing business’ environments. This framework organizes several key components into a cohesive structure that facilitates an in-depth examination of how these elements interact. At its core, the framework posits that the relationship between economic liberalization policies and export performance is influenced by several interconnected factors.

Law and order (LaO): Law and order have become tools of oppression and repression in the economic world [48,49,50]. Most of the time, they are measured based on the World Bank role of law index or ease of doing business score. Agent theory of firms helps to analyze how government incentives (tax breaks, subsidies) align firm behavior with national export goals. Laws must be enacted to implement new economic policies and structural adjustments. These researchers further state that, under our national law, the government provides guarantees such as the right to work and the ability to enter and depart the enterprise. When corporations have clearly located legal entities to target, using law as a weapon is appealing and practical, but globalization has increased the variety of decisions being made “by remote control” or even in a never-never land located in cyberspace [51]. There is a concern that they act outside the law as well. Legislators face a two-fold opposition when drafting new regulations to address this occurrence.

Incentive schemes (InSs): The constant reduction in trade barriers, combined with the creation of supporting incentives, has reduced the cost and motivation for carrying out business [52,53]. Government spending on exports in the form of industry subsidiaries or tax incentives (as a percentage of GDP) is used to quantify government incentives. According to [54,55,56], incentive shames comprise the removal of tariff barriers (such as tariffs, surcharges, and export subsidies) on the one hand and non-tariff hurdles on the other (such as licensing regulations, quotas, and arbitrary standards). The integration of the resource-based view supports the theoretical development of how incentives allow businesses to develop dynamic capabilities (innovation, supply chain agility) or acquire export-specific resources (technology, skilled labor). Most developing countries, such as Ethiopia, have implemented trade reforms with the primary goal of raising people’s living conditions, boosting market efficiency, and promoting the export industry. This would encourage foreign direct investment, which would indirectly help factor allocation [57].

Trade openness (TrO): The degree to which a nation integrates into the global economy through laws and practices that promote cross-border commerce in capital, products, and services is the operational definition of openness to trade in this study. Export and economic growth require open economic policies for trade with the rest of the world [23,44,57]. In liberalized marketplaces, Krugman’s new trade theory promotes an emphasis on network effects and economies of scale. Trade openness exposes businesses to international competition, which promotes specialization and efficiency. Due to these orientations, trade liberalization has arisen in most LDCs as part of a structural reform program. However, in related arguments, a wide range of jargon is used to define the amount of international economic integration, such as trade openness; it is not clearly defined and conceptualized [12,57,58]. When researchers argue about general growth in economic openness over recent decades, terms such as economic integration, trade liberalization, and globalization have been frequently employed [59].

Trade transparency can be quantified using the export + import/GDP function or other metrics from the economic freedom index [(export + import)/GDP]. In some cases, countries employ the economic freedom index on their own. The meaning of openness, further confusing how it is measured, has changed dramatically over the last three decades [57]. Ethiopia intends to open the market further by implementing policy reforms such as the privatization of major state-owned firms [60]. The measure of trade openness can comprise both qualitative and quantitative dimensions. The evaluations of a nation’s trade policies and practices by international organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) can be used to gauge trade openness. Qualitative assessments of a nation’s trade regime’s openness are frequently included in these appraisals. In addition to these parameters are qualitative assessments by specialists or think tanks that assign a ranking or rating to national economies according to their trade policy.

Classical economists like David Ricardo and Adam Smith are credited with coining the phrase and ideas of economic liberalization. These classical economists were interested in the advantages and disadvantages of liberal economy, as well as the impact of global trade on the home economy. Economic openness first affects the size and growth of a national economy through transcontinental trade transactions (imports and exports). The actual volume of recorded imports and exports inside a country’s economy serves as a gauge for openness.

Competitive priorities: Competitiveness is a key factor to consider in most strategic marketing studies. Competitiveness can be measured at national, industrial, and firm levels. Nations can compete only if their enterprises can compete; in international markets, firms, not nations, can compete [25]. Competitive advantage refers to the circumstances or capabilities that allow a corporation to outperform its competitors [26]. Thus, to achieve a competitive advantage, an organization should also consider its own external position and internal capability [27]. Trade liberalization reshapes sectorial export preferences depending on a country’s capabilities, as explained by Ricardian comparative advantage theory. The new form of international competition continually changes the rules of the game under the global business environment and calls for more alert and aggressive competitive moves through competitive priorities [33,37].

Accordingly, to effectively compete, firms must develop tactics and strategies [31,33]. Broadly, manufacturing firms must shift from competing for endowments or comparative advantages to competing for competitive advantages arising from superior or distinctive products and processes [38]. Competitive advantage includes factors or capabilities that enable a company to show a better performance than competitors [26]. Thus, to achieve a competitive advantage, an organization should also consider its own external position and internal capability [27].

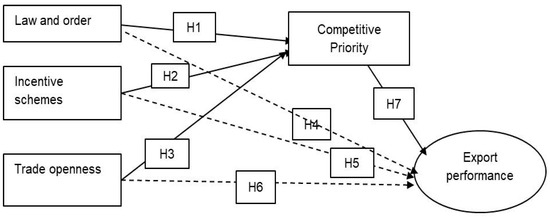

Regarding the dimension of competitive priorities, there is broad agreement that they can be expressed in terms of some basic components: cost, quality, and flexibility are the most common competitive priority measures [39,40]. The integration of these elements into a single conceptual framework provides a comprehensive approach to understanding how economic liberalization affects export performance in the context of Ethiopian privatized manufacturing firms. It offers policymakers, practitioners, and stakeholders valuable insights into the multifaceted relationships at play. The structural relationships among these variables are illustrated in Figure 1, highlighting how each component interacts with and influences the others.

Figure 1.

The relationship between independent and dependent variables (competitive priority) as a mediating role.

4. Methodology

To broadly address the research objectives, a mixed-methods research approach was employed. This methodology enables the integration of both qualitative and quantitative data, enriching the analysis of the complex relationships among the economic liberalization, competitive priorities, and export performance of Ethiopian manufacturing firms. As noted by [61], research design functions as a blueprint for the systematic collection, measurement, and analysis of data; thus, an appropriate research design is crucial. Therefore, this study incorporates both descriptive and explanatory research designs to achieve a holistic understanding of the subject. Utilizing a mixed-methods approach is decisive, as each method can mitigate the limitations of the other. There are potential compatibility issues in mixed-methods research, advocating for the simultaneous use of qualitative and quantitative data to enhance the understanding of social dynamics. Consequently, this methodological framework has gained acceptance in contemporary research, underscoring the importance of multifaceted approaches [62].

Wholly privatized manufacturing firms, those that are appealing in international marketing through exporting, are the unit of analysis for this research. These firms vary extensively in terms of their level of economic strength, firm competitiveness, and production and marketing capacity. As stated in (Table 1), a total of 160 of the 370 firms that are being privatized under the privatization initiative fall within the manufacturing category, according to the CSA 2014. Data were collected from 114 privatized (ownership was transferred from the government to the private owners) manufacturing firms across various categories, employing proportional stratified sampling techniques (Table 1). These firms exhibit diverse categories in production capacities, marketing strengths, and levels of economic stability [63,64]. All participating firms engage in international export marketing.

Table 1.

Sample size determination (number of privatized firms from 1991 to 2014).

The total sample size was determined by using the following sampling size determination formula developed by [65]:

where n = sample size; N = size of population; and e = precision level (Cochran, 1963). According to the above formula, the total sample size for the total number of firms included under investigation is calculated at 95% degree of significance as

The data collection employed the key informant technique, as utilized by prior studies [34,66,67]. This approach enabled the researcher to gather insights from knowledgeable individuals, ensuring that the data accurately reflect the firms’ competitive strategies and export capabilities. The researcher subsequently divided the entire number of samples proportionately among the different kinds of privatized factories after determining the overall sample size. Furthermore, the researcher computed Bartlett’s test of sample adequacy and Keiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) to make sure that the factor analysis produced distinct and trustworthy factors.

To determine the sample size, a proportional stratified sampling technique was applied from each manufacturing category (strata). Since 1995, approximately 370 state-owned enterprises across various sectors have undergone privatization, with 160 in the manufacturing sector privatized [65]. This study determined a total sample size of 114 firms at a 95% confidence level, ensuring robust representation.

Data pertaining to all constructs were subjected to exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to identify the most significant dimensions of the variables. Following this, structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to confirm the relationships among the underlying dimensions of the indicator variables. Principal components analysis with varimax rotation was utilized to clarify the linear components present in the data, revealing how specific factors contribute to the identified components. This psychometric approach offers a sound and conceptually straightforward method for analyzing complex relationships within the dataset [68]. By combining these methodologies together, this study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the influence of economic liberalization on the export performance of privatized manufacturing firms in Ethiopia.

5. Data Analysis

The results of the statistical estimations outline the key features of the research variables examined. The analysis reveals that trade openness and law and order exhibit the highest means and lowest standard deviations, with means of 4.69 and 4.67 and standard deviations of 0.380 and 0.3825, respectively.

These findings indicate that both law and order, along with incentive schemes, significantly contribute to the export performance of manufacturing firms, as shown in Table 2. Along with measures including law and order, incentive programs, trade openness, competitive priorities, and export success, descriptive statistics highlight the significant policy changes following the 1991 reforms. Indicators’ mean counts and standard deviations are displayed here to demonstrate how liberalization and policy changes affect Ethiopian manufacturing companies’ export performance. Furthermore, the results highlight that trade openness and the competitive priorities of firms, including cost, flexibility, and quality, have a significant effect on the export performance of privatized manufacturing firms in Ethiopia.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

6. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Prior to conducting multivariate analyses, essential assumptions regarding sample size, variable scale, normal distribution, multicollinearity, and outliers were assessed following the recommendations of [31,53]. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) could be able to assist the researcher in identifying latent drivers of export performance, also known as hidden determinants or policy-related factors, so as to develop focused interventions for Ethiopian manufacturing firms. Based on [69], a sample size of 100 to 200 observations is generally deemed adequate. Therefore, the sample of 114 firms utilized in this investigation is considered appropriate. The assessment of skewness and kurtosis for the study variables indicated that they fell within permissible limits, suggesting that the data distribution was relatively symmetric [34,52]. Correlation analyses showed that multicollinearity was not a concern, as all correlations were below 0.9.

There are no statistical breaches in this study, which is one of the multivariate model’s key assumptions. Due to this study’s requirements, EFA with varimax rotation was used to test the construct’s unidimensionality [70]. The inter-relationships between the items on the measurement scale were investigated via EFA. Items having a factor loading of less than 0.5 were removed throughout the validation procedure [70]. Cronbach’s alpha is the most often used method for determining the scale’s internal consistency or homogeneity [54].

The statistics on reliability and validity are shown in Table 3. Law and order (LawO) = 0.90, incentive schemes (IncSs) = 0.89, trade openness (TradO) = 0.83, competitive priority (ComP) = 0.88, and export performance (ExoP) = 0.83 were the alpha values for each factor. These alpha values were higher than the permitted minimum of 0.70 [54,71].

Table 3.

Summary statistics of measurement model.

Each latent construct achieved a CR well above the threshold of 0.70, indicating strong internal consistency. Discriminant validity was assessed using the approach recommended by [54]. As indicated in (Table 3), these alpha values exceed the acceptable minimum of 0.70.

The variance inflation factor (VIF) values from the collinearity statistics ranged from 1.208 to 5.853, suggesting no multicollinearity issues, as VIF values falling between 1 and 10 indicate acceptable levels [59]. Additionally, as supported by [53,63,64], all items within the measurement model were found to be statistically significant and reliable. Furthermore, Table 3 and Table 4 illustrates that composite reliability assessments confirmed construct reliability, with all values greater than 0.7 [23,71].

Table 4.

Factor loading for each research variable under EFA.

The k-values for all items are substantially above 0.50, the CR of each component is greater than 0.7, and the AVE of each factor is greater than 0.5, showing that the model has good convergent validity. According to [72], when real factor loadings are considered instead of presuming that each item was fairly weighted during composite load assessment, CR is a good predictor of convergent validity. All of the latent constructs have a CR that is not only within acceptable boundaries but also far exceeds the criterion of 0.7. Overall, the findings demonstrate that the measuring of latent components is internally consistent. The discriminant validity was also assessed based on a method proposed by [72]. The results suggest that the squared correlation between constructs should be less than the variance extracted by either of the individual constructs.

Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), as per the guidelines outlined by [73,74,75]; three criteria were employed to evaluate convergent validity: (1) factor loadings (k) for all indicators should exceed 0.50; (2) composite reliability (CR) must exceed 0.70; and (3) the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct must exceed 0.50. Table 3 demonstrates convergent validity, with all item loadings significantly above 0.50, CRs for each construct exceeding 0.70, and AVEs for each factor greater than 0.50. It is worth noting that CR is a robust predictor of convergent validity when genuine factor loadings are considered rather than assuming an equal weight for all items during composite assessment [53,76,77]. Generally, the data analysis substantiates the validity and reliability of the research constructs, providing a solid foundation for understanding the relationships between economic liberalization policies and the export performance of privatized manufacturing firms in Ethiopia.

In the same way, discriminant validity is vital for confirming that distinct constructs indeed measure different dimensions of the research phenomenon, as emphasized by [54,78,79]. One effective method for assessing discriminant validity is through the average variance extracted (AVE), in conjunction with the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which states that the square root of each latent variable’s AVE must exceed the correlations between that variable and all other latent variables.

This criterion indicates that the variance captured by each latent variable is greater than the common variance with any other variable. In the output from Smart PLS, correlations are displayed below the square root of the AVE in the diagonal cells of the Fornell–Larcker table. To determine discriminant validity, if the square root of the AVE for a latent variable (displayed in the diagonal) is greater than the corresponding values below it in the same column, we can conclude that discriminant validity is binding. As shown in Table 5, the square roots of AVEs are greater than the related correlations, supporting the conclusion that discriminant validity has been established in this study. Moreover, adherence to the Fornell–Larcker criterion suggests that this study does not exhibit statistical violations of fundamental assumptions inherent in multivariate modeling.

Table 5.

Discriminate validity.

In accordance with the study objectives, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with varimax rotation was utilized to test the unidimensionality of the constructs [80,81]. The analysis facilitated an examination of the inter-relationships among items within the measurement scale. Any items that yield factor loadings below the threshold of 0.5 were systematically removed during the validation process [56,82].

An optimal factor loading is characterized by “simple loadings,” where projected loadings exceed 0.7 [53,65,82]. Table 5 confirms that every indicator correctly loads onto its corresponding factor. In a robust measurement model, each indicator should align closely with the concept that it is intended to measure and display minimal cross-loadings with unrelated constructs. Specifically, the measurement items must load significantly on their designated constructs while demonstrating the smallest loadings on others, confirming an appropriate pattern.

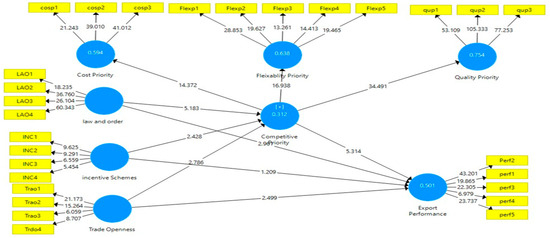

7. Factor Loading, p-Value, and T-Statistics

The optimal factor structure projected loadings would be larger than 0.7 [53,81,83]. Every indicator in the aforementioned Table 6 is correctly loaded on its corresponding factor. Indicators in a good model should load properly on the items that they are intended to measure and should clearly show any cross-loadings with elements that they are not intended to measure. When the measurement item loads substantially on its theoretically assigned component but not heavily on others, the correlation between the latent variable score and the measurement item must show an appropriate pattern of loading. When the other variables were cross-loaded, the loadings in this case all showed a loading pattern that was more appropriate [1,61,79]. None of the indicator variables should, at the very least, correlate more strongly than the others.

Table 6.

Path coefficient: mean, STDEV, T-values, and p-values.

In this study, all cross-loadings displayed a clear pattern where all indicators loaded positively onto their projected factors [54,79,84], ensuring that no indicator variable had a stronger correlation with an unrelated variable. The factor loadings for all indicators exceeded the critical threshold of 0.5, thereby validating their relevance [22,27,85].

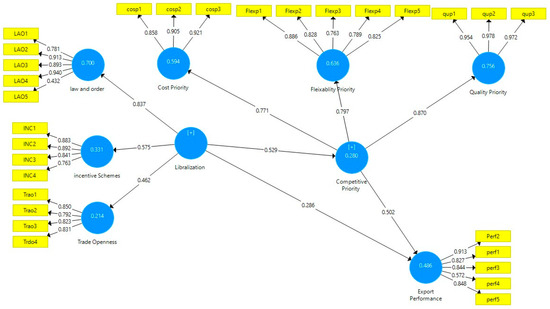

As shown in Figure 2, initial factor loading, the law and order indicator (LaO5) score was 0.432, which is below 0.5, and thus it was removed.

Figure 2.

Initial factors loading.

The factor loadings for the other indicators were all above the critical value of 0.5 for every item, as reported by [22,69,85]. As indicated (Table 5), composite reliability was tested to verify the construct reliability as well, and the results show that every value was higher than 0.7 [23,72]. The structural model was generated as shown in Figure 3 after removing the lower factor loading value (also see Table 7).

Figure 3.

Exploring the relationship between Law and order, incentive schemes, trade openness, competitive priority, and export performance model with SEM results.

Table 7.

Total direct and indirect effect.

The structural model, presented in Figure 3, was generated following the exclusion of items with lower factor loadings, ensuring robustness in the measurement framework. Consequently, the analyses substantiate both the discriminant and convergent validity of the constructs utilized in this study, providing confidence in the reliability and integrity of the measurement model employed to explore export performance and economic liberalization policies among privatized manufacturing firms in Ethiopia.

8. Export Performance Structure of Manufacturing Firms in Ethiopia

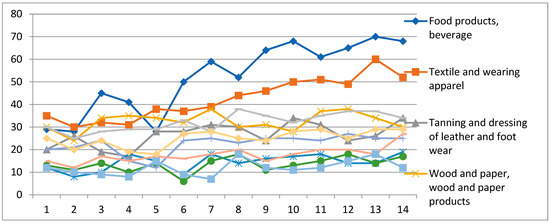

The export performance of Ethiopian privatized industries fluctuates over time. The food and beverage sector generally has the highest of all export shares over the past 15 years in the Ethiopian manufacturing sector export share. As stated in Table 8, the growth in the share of the subsectors of publishing and printing services and chemicals and chemical products during the same year was considerably truncated [86].

Table 8.

Export performance structure of private manufacturing firms in Ethiopia from 2010 to 2023.

Despite some improvement, Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector still confronts major obstacles in terms of export performance, consistency, productivity, and competitiveness. The three main industrial sectors as see (Figure 4)—food products, beverages, textiles, and clothing—saw comparatively steady and notable development. Infrastructure development, focused legislative interventions, and a move toward higher-value, technology-driven businesses are all necessary to address these problems. Since 1991, Ethiopian manufacturing firms’ export performance structure has been characterized by structural obstacles, poor export orientation, and the predominance of low-value items. Although there is some promise for development due to recent reforms and industrial strategies, there are still many obstacles to overcome. It will take consistent work to increase production, diversify exports, and fortify ties within the economy in order to overcome these obstacles.

Figure 4.

Export performance structure of private manufacturing firms in Ethiopia from 2010 to 2023. Source: Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MOFED), Ethiopia’s economic outlook (2024): Fiscal policy and growth strategies.

H1.

Stronger law and order (e.g., contract enforcement, property rights protection) positively influences a firm’s competitiveness by reducing operational risks and transaction costs.

The main objectives of the economic reform initiatives in Ethiopia consist of tax reforms, import tariff reduction, market liberalization, and the elimination of subsidies. Macroeconomic stability and a favorable government policy climate brought about by economic reform energized the private sector, which had been stifled under the military regime prior to 1991 [87]. Previous studies, including those by [48,75], emphasize that a government’s ability to uphold a robust legal framework and enforce laws significantly enhances a firm’s competitive edge in the global market. The findings of this research indicate that stronger law and order, particularly when it comes to protecting property rights and enforcing contracts, substantially reduce transaction costs and operational risks, which boosts a company’s competitiveness in Ethiopia. Research by [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] further supports the notion that a stable legal environment facilitates contract enforcement, intellectual property protection, and equitable dispute resolution. Such an environment inculcates confidence in businesses, encouraging them to invest and operate internationally with the assurance that their rights are safeguarded. Additionally, a strong legal system mitigates corruption and fosters transparency, thereby boosting firm competitiveness on a global scale. Furthermore, firms experience less operational uncertainty when contracts are enforced and the legal system is robust. Knowing that their property rights are protected and that agreements will be upheld gives them greater confidence when making long-term investments. This stability creates an atmosphere that is favorable for corporate expansion by drawing in both domestic and foreign capital. However, in this study, the p-value for law and order was 0.187, exceeding the 0.05 threshold, which prevents the null hypothesis from being rejected.

H2.

Firms with robust legal foundations experience higher export performance due to enhanced investor confidence and reduced trade disputes.

As a least developed nation, Ethiopia enjoys a number of advantages with special and preferential treatment, such as the Agricultural Growth Opportunity Act (AGOA from the USA), the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) scheme, and Everything but Arms (EBA). Nevertheless, exporters encounter difficulties in these and other international markets. For example, tariff barriers still make it difficult for the least developed nations to enter the industrialized nations’ markets. Value-added export tariffs continue to rise in the markets of developed nations.

Incentive schemes are vital tools for attracting and retaining top talent, motivating employees to exceed expectations and aligning individual efforts with organizational goals [22,50,89]. Well-structured incentive plans stimulate innovation and creativity, leading to the development of new products and services that provide a competitive advantage in global markets. The significance of incentives is further confirmed by a p-value of 0.045, which is below the 0.05 threshold, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis. Effective legal structures guarantee that transactions, whether they involve buying products, obtaining loans, or forming partnerships, are completed in an organized manner. Businesses can avoid expensive legal battles or additional work to protect their rights when contracts are enforced effectively. Instead of focusing on risk mitigation, this efficiency enables businesses to devote more resources to innovation and growth. Prior research corroborates that incentive schemes positively influence a firm’s competitive priorities in the international arena [50,51]. These programs boost employee motivation, productivity, and overall performance, which are crucial for success in a competitive global environment.

H3.

Government incentive programs (export subsidies, R&D grants) improve a firm’s competitiveness by enabling investments in innovation and productivity.

Trade openness significantly enhances a firm’s global competitiveness [12,57]. By removing barriers such as tariffs, quotas, and foreign investment restrictions, countries foster an environment where firms gain access to new markets, resources, and technology. The findings from this study confirm the positive relationship between trade openness and competitive priorities, with a p-value of 0.000, indicating a highly significant effect at all standard alpha levels. Incentives from the government can be quite important for encouraging innovation in businesses. Assistance from incentive schemes helps businesses in Ethiopia, where industries are still in the early stages of development, to invest in new technologies, enhance the quality of their products, and adjust to international norms, all of which boost their competitiveness. While it is difficult to find an African nation that does not have free trade zones and regional trade agreements, Ethiopia is among the least integrated within the framework of African regional agreements when compared to its peers. It is still merely a member of COMESA (preferential trade arrangement), has no free trade area agreements, and is joining the WTO as an observer. Its reluctance to integrate into regional and international markets indicates that its industrial sector is underdeveloped and struggles to compete, even when faced with the market of developing nations. Due to the industrial sector’s poor performance, the nation was unable to integrate with other partners, reach other locations, and participate fully in global value chains.

H4.

Firms utilizing incentive programs exhibit higher export performance due to improved cost efficiency and market penetration capabilities.

By “regulatory environment,” we mean the degree of transparency and change in regulations. According to [90,91], it involves minimizing corruption, decreasing partiality in decision making, and increasing government transparency. Therefore, another crucial element that might affect the nation’s appeal to the international market, which acts as a stimulant to grow the industrial sector, is the regulatory environment. While lowering corruption and bribery, effective institutions, open government policymaking, and responsive administrative processes are harmful elements, eliminating government officials’ partiality in decision making enhances capital inflow, which raises the production of produced goods.

Government strength in ensuring legal certainty, protecting property rights, and enforcing contracts is crucial for enhancing a firm’s export capabilities. A robust legal and regulatory framework fosters an environment conducive to international trade [5,6]. The financial cushion that export subsidies give businesses allows them to investigate overseas markets. Ethiopian businesses can lessen their reliance on the home market and increase their overall competitiveness by reaching a wider audience abroad. Additionally, this pushes businesses to broaden the range of products that they offer, which helps them to adjust to shifting market conditions. However, the analysis reveals that the p-value for law and order with respect to export performance is 0.196, which is not significant at the 0.05 level. Incentive programs can create a favorable environment for both domestic and foreign investments. A government’s commitment to fostering innovation can attract foreign investors interested in tapping into new technological developments and expanding market opportunities in Ethiopia. Despite prior findings by [50,65] suggesting that government law and order positively affect export success, this study’s results imply that the current legal environment may not be sufficient for bolstering export performance significantly.

H5.

Greater trade openness (lower tariffs, FTAs) enhances enterprise competitiveness by exposing firms to global best practices and competitive pressures.

Incentive schemes can play a pivotal role in maximizing a company’s export potential through financial support and export promotion initiatives. Ethiopian manufacturing firms can interact with other markets due to trade openness, where they acquire and adopt best practices in technology, production, and management from around the world. As businesses adjust to international norms to remain competitive, this exposure boosts operational effectiveness, product quality, and innovation. In the context of privatized Ethiopian manufacturing firms, the incentive scheme had a significant p-value of 0.034, allowing us to reject the null hypothesis that stated otherwise. Reduced tariffs and free trade agreements put local enterprises at risk of increased competition from overseas businesses. The result grows more customer-focused and efficient while simultaneously increasing pressure on them to enhance their cost structures, procedures, and products. In the long term, this competitive climate can spur innovation and raise the industry’s level of overall competitiveness. Prior studies [51,53,58] consistently support the notion that incentive programs enhance export performance by motivating firms to expand their market reach and boost export earnings.

H6.

Trade openness is positively associated with export growth as it facilitates access to larger and more diversified international markets.

A high degree of trade openness allows firms to access markets, achieve economies of scale, and secure crucial resources [52]. Since trade openness increases a nation’s access to larger and more diversified foreign markets, it is a key factor in export growth. Countries can boost their competitiveness, expand their consumer base, and gain from economies of scale by lowering trade restrictions like tariffs and quotas. Trade openness is an essential part of a country’s economic strategy because of the increasing engagement in the global market, which not only promotes economic growth but also efficiency and creativity. This study finds a p-value of 0.000 for trade openness in relation to export performance, confirming its significant impact at the 0.05 level. The evidence suggests that countries that remove trade barriers significantly improve firms’ export capabilities, thereby facilitating sustained economic growth.

H7.

The interaction of strong law and order, incentive schemes, trade openness, and competitiveness of the firm is positively associated with export performance.

The analysis indicates that the competitive priorities, specifically cost and quality flexibility, exert significant influences on the export performance of privatized firms in Ethiopia. This is supported by adjustments in market share, profit margins, and levels of export satisfaction. The model confirms that trade openness, incentive schemes, and law and order jointly contribute to export performance at standard significance levels. Strong law and order, incentive programs, trade openness, and company competitiveness all help to improve export performance. Access to international markets is made easier by trade openness, and a firm’s competitiveness guarantees that it can successfully satisfy the needs of these markets. When combined, these elements produce a favorable atmosphere for improving export performance, which promotes economic expansion and advancement. Despite the slow reform process and limited engagements within the industrial sector, these findings highlight a need for more robust policies that effectively enhance firm competitiveness in the global market [53,54]. While current policy measures have not drastically improved performance, understanding these dynamics may help to shape future strategies aimed at accelerating economic growth and enhancing competitiveness. This analysis demonstrates that foundational constructs such as law and order, incentive schemes, and trade openness are critical drivers of both competitive priorities and export performance in the manufacturing sector. Further research and policy efforts should aim to strengthen these areas to support sustainable growth for Ethiopian manufacturing enterprises in the global marketplace.

9. Discussion

This study’s ultimate goal is to provide light on how Ethiopia’s economic liberalization following 1991 affected manufacturing companies’ performance, especially in terms of their ability to export in a cut-throat global market. Ethiopia’s economy changed from being centrally planned to being market-oriented with the overthrow of the Derg dictatorship in 1991. Trade liberalization, state-owned firm privatization, and deregulation were among the economic liberalization measures implemented. These could include lowering tariffs, removing price controls, providing incentives for foreign direct investment (FDI), and allowing for competition in a number of industries.

Since the commencement of economic reforms in Ethiopia in 1991, law and order (LaO), incentive schemes (InSs), and trade openness (TrO) have emerged as fundamental components of the nation’s liberalization and privatization efforts [50,51]. This study also confirms that these elements make significant contributions to the export performance of privatized firms. Collectively, they enhance export capabilities, attract foreign investment, and create a favorable business climate essential for economic growth. To ensure the effectiveness of these measures, it is crucial to sustain political and legal reforms, strengthen the incentive programs, and foster genuine trade openness.

The relationship between economic liberalization, a firm’s competitive strategies, and export success in Ethiopia is complex and multifaceted [7,54]. While liberalization creates opportunities for companies to enhance their competitive tactics, overcoming legislative and infrastructural challenges is imperative for these strategies to succeed in the global marketplace. Ethiopian firms must leverage the benefits of liberalization by aligning their competitive priorities with the demands of international markets to achieve sustained growth.

Ethiopia’s commitment to liberalizing its economy has manifested in significant reforms, particularly through the privatization of state-owned enterprises across various sectors. The primary objectives of these reforms are to boost export performance, attract foreign investment, and enhance overall competitiveness [50,51,92]. Policymakers and business leaders must recognize the intricate connections between economic liberalization, competitive priorities, and export performance to foster a thriving economic environment. Ethiopia’s strategic initiatives aim to enhance trade, attract investment, and create stability within the business landscape, contributing significantly to the overall economic health.

The presence of law and order provides businesses with an operational environment free from arbitrary actions and instability, as noted by [48]. The government has undertaken judicial reforms aimed at improving the effectiveness and transparency of the legal system. Enforced laws protect property rights and ensure fair competition, which are crucial for bolstering investor confidence. The study findings underscore the importance of enhancing the capacities of law enforcement organizations. Efficient dispute resolution mechanisms are vital for domestic and foreign investors. The supporting literature [53], reinforces the idea that ensuring public safety and security is essential for corporate prosperity. The government’s prioritization of law and order can significantly mitigate the risks associated with investing in Ethiopia.

The findings also indicate that, in order to stimulate both domestic and foreign investment, the Ethiopian government has implemented various incentive programs, such as reduced tariffs, tax holidays, and industry-specific subsidies. By promoting investment in export-oriented sectors, these incentives encourage commerce and enhance competitive positioning in global markets. Export-oriented programs that encompass training, financing for exporters, and market intelligence serve as critical tools for businesses seeking to gain a competitive edge [46]. Moreover, supporting research and development (R&D) can further foster innovation and improve product quality. Special economic zones (SEZs) with enhanced infrastructure and favorable regulatory frameworks are also instrumental in attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and promoting export-oriented production. These zones often provide efficient logistics networks, streamlined customs procedures, and attractive fiscal incentives.

Increasing trade openness through the removal of tariffs and non-tariff barriers can broaden exporters’ market access. Enhanced trade openness benefits both domestic firms and foreign enterprises by providing greater access to international markets and advanced technologies. Ethiopia’s active engagement in regional trade agreements can facilitate improved market access for Ethiopian products. Such agreements can also lead to collaborative infrastructure projects aimed at bolstering trade logistics. A positive correlation exists between trade openness and the ability to attract foreign investment, which brings funds, technology transfer, and expertise into the local economy. Furthermore, increased trade openness generates a competitive environment that drives local firms to innovate and enhance efficiency.

For firms aiming to succeed in global markets, competitive priorities such as affordability, flexibility, and quality are paramount [50,89]. This study assessed competitive factors that influence export performance in the Ethiopian manufacturing sector. Establishing cost leadership allows companies to set competitive prices, making their products appealing to global consumers. Companies can enhance profitability by minimizing production costs through efficient resource management, economies of scale, and process refinements.

Flexibility, defined as a firm’s capacity to adapt to shifting consumer demands, specifications, and market conditions, is vital for maintaining a competitive edge in a rapidly evolving global landscape. The ability to swiftly modify manufacturing processes, alongside volume flexibility, can give firms a distinct advantage. Furthermore, a brand’s ability to deliver high-quality products is crucial for gaining customer loyalty and market share. Many Ethiopian manufacturing firms may face challenges in establishing robust quality control systems, which can hinder their ability to maintain consistent product quality. Limited access to cutting-edge technologies further complicates efforts to uphold quality standards.

Ethiopia’s economic reforms, encompassing law and order, incentive schemes, and trade openness, are pivotal in shaping the export performance of privatized firms. Despite the progress made, there remains a pressing need for continuous improvements to the legal framework, infrastructure, and policies that foster a competitive business environment. Achieving sustained growth and competitiveness in the global market will require Ethiopian firms to strategically align their competitive priorities with the dynamics of international trade.

10. Conclusions

Economic liberalization reform in Ethiopia has significantly transformed the landscape of international marketing by removing obstacles, encouraging competition across borders, and increasing market accessibility. The manufacturing sector has seen some improvement in export performance as a result of economic changes adopted after 1991, such as lowering tariffs, promoting private sector involvement, and liberalizing trade regulations. By exposing local businesses to global standards, technologies, and practices, these reforms increased their competitiveness and made it easier to access global markets. Manufacturing firms were able to increase their international reach because of continuous government policy support through export promotion programs, which include export processing zones (EPZs) and exporter incentives.

In order to take advantage of new prospects of economic liberalization and world economic integration, manufacturing firms must strategically align competitive priorities, including cost effectiveness, product quality difference, customer centricity, and flexibility.

Ethiopia created new opportunities for its industrial companies to interact with the global economy by joining international organizations and signing trade agreements. Ethiopian companies’ export performance increased as a result of the removal of trade restrictions and tariffs, as well as the implementation of export promotion laws. Additionally, businesses were able to diversify their export destinations as a result of the proliferation of free trade agreements (FTAs).

Success in this dynamic environment, however, also depends on agility, as businesses must constantly adjust to shifting market needs, competitive challenges, and regulatory changes. This dependency must be acknowledged by both the firm’s executives and policymakers, who should make sure that investments in labor skills, R&D, and digital infrastructure complement economic changes. In the end, sustainable export development is driven by the convergence of liberalized markets and strategic firm priorities, which positions companies to prosper in a global economy that is interconnected.

However, a number of internal issues continued to limit Ethiopian manufacturing companies’ export performance in spite of these beneficial effects. These include the requirement for higher production standards, low technological skills, poor infrastructure, and restricted access to financing. Markets were opened by liberalization, but many businesses were still ill-prepared to compete with more seasoned overseas producers or to reach international quality requirements.

11. Implications for Future Research

The findings from this study provide crucial insights into the interplay between competitive priorities and export performance in the context of economic liberalization within Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector. As the Ethiopian government emphasizes law and order, offers diverse financial and non-financial incentive packages, and advocates for trade openness, manufacturing firms are encouraged to enhance their competitiveness in the global marketplace. This research holds practical implications for international marketing managers in export-oriented companies, highlighting the need to align their strategies with the national reforms aimed at fostering a healthier business environment.

Although Ethiopia’s liberalization strategy has promise, it requires a slight balancing act between institutional resilience and market reforms. Diversifying exports, enhancing governance, and encouraging FDI in high-impact industries are top priorities. Complementary measures that address structural barriers and protect macroeconomic stability are essential for success. A phased approach in economic liberalization would allow local industries to adjust, develop regulatory capacity, and reduce risks associated with reforms. Rapid sector liberalization would cause economic instability.

To improve governance and investor trust, merit-based civil services, open regulatory frameworks, and anti-corruption initiatives should be created; the export portfolio should be diversified by moving away from low-value agricultural exports and toward higher-value manufactured goods like processed commodities, textiles, and leather goods; and competitive labor prices and preferential trade accords, such as AGOA and other regional and international agreements, should be taken advantage of. The nation should enlarge its industrial zones to draw foreign direct investment in light manufacturing and production.

Despite the significance of these findings, there is a notable gap in empirical research exploring the relationship between a firm’s export performance and its competitive priorities in the context of liberalization. Ethiopia should improve regional integration and broaden market access and align its trade policies and tariffs with those of the African Continental Free Trade Area. If there are any export restrictions on important products, they should be lifted to promote regional trade and manufacturing. Public–private partnerships and international partners should be worked with to update logistics infrastructure. Future studies should focus on this under-researched area, examining how specific dimensions of competitive priorities, such as cost, quality, flexibility, and innovation capabilities, influence the export outcomes of firms operating in transitioning economies. Moreover, subsequent research should investigate the nuances of how firms internally adapt their strategies in response to the macroeconomic shifts driven by liberalization.

The strategic goal of industrialization and national competitive advantages should be supported by Ethiopia’s sectorial priorities and efforts to attract foreign direct investment. In order to lower the danger of corruption, bureaucratic delays, and weaker property rights for investors, Ethiopia also seeks to enhance contract enforcement and judicial efficiency. In addition, it should be made easier for businesses to register and obtain licenses.

Economic liberalization is recognized as a macroeconomic driver influencing international marketing; however, it is essential to consider the micro-environmental factors that also play a critical role. These include a firm’s previous experiences in international markets, managerial commitment, strategic direction, and even the size and scale of operations. Future research should explore how these micro-level factors interact with macro-level changes to affect export performance.

Importantly, the Ethiopian government’s commitment to fostering economic liberalization must include not only the establishment of law and order but also a sustained focus on removing barriers associated with authoritarian governance. Policymakers should prioritize the implementation of supportive measures, such as enhanced access to financial incentives for export-focused enterprises, to cultivate an open and competitive business climate.

This research identifies competitive priorities such as quality, flexibility, and value as significant influences on the export capabilities of Ethiopian manufacturing. Nonetheless, challenges persist, ranging from high energy costs and limited raw material availability to inadequate infrastructures—which contribute to inflated production costs. While Ethiopia benefits from low labor costs, harnessing this advantage demands a concerted effort to improve productivity across manufacturing sectors. Future investigations could delve into specific strategies that firms might adopt to mitigate these challenges and enhance their competitiveness, such as investing in technological advancements or forming strategic partnerships. Inclusively, these implications underscore the necessity for ongoing research to establish a clearer understanding of how firms can navigate the complexities of economic liberalization and leverage their competitive priorities to optimize export performance. By addressing the gaps identified in this study, future research can contribute to the development of more effective policies and practices that support the growth of Ethiopia’s manufacturing sector in the global market.

12. Limitations of This Study

This research has some limitations that should be considered when the authors interpret the results. Particularly, the researchers used cross-sectional data, which did not allow us to examine the real causality between the different measures studied or to specify changes in the variables over a certain period. Macroeconomic environments were volatile in nature. In this respect, a longitudinal study may be the most effective approach for studying the export performance of firms at different times. The selected sample size is also another limitation: if the number of samples increases the possibility for precision will be high if other factors remain constant, so further research can focus on a wider variety of sectors, including services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; methodology, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; software, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; validation, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; formal analysis, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; data curation, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; writing—review and editing, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K.; visualization, M.A.E., A.E.A. and A.T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biramo, A.H. Export Performance of Oilseeds and ITS, Determinants in Ethiopia. Am. J. Econ. 2011, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Trade and Development Report 2010: Employment, Glob-Alization and Development. United Nations. 2010. Available online: https://unctad.org/publication/trade-and-development-report-2010 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- National Bank of Ethiopia. National Economic Report for the Year, 2019/20; Addis: Abeba, Ethiopia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararajan, A.; Anindya, G. Evaluating Pricing Strategy Using e-Commerce Data: Evidence and Estimation Challenges. Inst. Math. Stud. 2006, 21, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Oqubay, A. Industrial Policy and Economic Transformation in Africa, and Made in Africa Industrial Policy in Ethiopia; Oxford Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thoumrungroje, A. The Effects of Globalization on Marketing Strategy and Performance; Washington State University: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pedró, F.; Leroux, G.; Watanabe, M. The Privatization of Education in Developing Countries: Evidence and Policy Implications (UNESCO Working Papers on Education Policy, No. 2). UNESCO. 2015. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233480 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Farooqui, S. Ullah Bilateral Trade and Economic Growth of China and India: A Comparative Study; Department of Commerce, Aligarh Muslim University: Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Tarek, B.H.; Adel, G.; Sami, A. The relationship between competitive intelligence and the internationalization of North African SMEs. Compet. Change 2016, 20, 326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Njikam, O. Export market destination and performance: Firm-level evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Afr. Trade 2017, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Udoidem, J.; Ikpe, E. Michael, Free Trade, Export Expansion and Economic Growth in Nigeria. J. Econ. Financ. 2017, 8, 2321–5933. [Google Scholar]

- Emagne, Y. Exploring the Relationship between Trade Liberalization and Ethiopian Economic Growth. Ethiop. J. Econ. 2017, 26, 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, R.E. Differences in Perceptions of Exporting Problems Based on Firm Size and Export Market Experience, Business, Economics, Sociology. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 28, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, J.A.; Williams, C.L. Export-Led Growth: A Survey of the Empirical Literature and Some Non-Causality Results, Part, I. J. Int. Trade Econ. Dev. 2000, 9, 261–337. [Google Scholar]

- Olivera, J.; Palomino, F.; Peydró, J.L. Sharing the costs of human capital investment through efficient mobility. Labour Econ. 2012, 19, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, N.; Neil, M. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, N. Probabilistic Non-linear Principal Component Analysis with Gaussian Process Latent Variable Models. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2005, 6, 1783–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Brulhart, F.; Gherra, S.; Quelin, B.V. Do Stakeholder Orientation and Environmental Proactivity Impact Firm Profitability? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 158, 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Musibau, A.; Babatunde, M.; Olawoye, O. The effects of internal and external mechanism on governance and performance of corporate firms in Nigeria. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2009, 7, 330–344. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, A.; Jiang, P.; Ahmad, M.; Khan, M.A.; Olah, J. The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Financial Development: New Evidence from Panel Cointegration and Causality Analysis. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan Winters, L. Trade Liberalisation and Economic Performance: An Overview. Econ. J. Febr. 2004, 114, F4–F21. [Google Scholar]

- Kingu, J.C. Export response to trade liberalization in Tanzania: A cointegration analysis. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 5, 1–11. Available online: https://www.iiste.org/Journals/index.php/JEDS/article/view/17837 (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Doan, H.Q. Trade, institutional quality and income: Empirical evidence for Sub-Saharan Africa. Economies 2019, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, F.; Zohlnhöfer, R.; Jathe, J. Partisan politics and economic intervention: Evidence from an aggregating approach. West Eur. Politics 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, R. Transformational leadership: The impact on organizational and personal outcomes. Emerg. Leadersh. Journeys 2008, 1, 4–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sadri, G.; Lees, B. Developing corporate culture as a competitive advantage. J. Manag. Dev. 2001, 20, 853–859. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, E.; Gittell, J.H.; Leana, C. High-Performance Work Practices and Sustainable Economic Growth. EPRN 2011, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T.; Saez, E. Inequality in the long run. Science 2014, 344, 838–843. [Google Scholar]

- Herzing University. 2014–2015 Academic Catalogue; Retrieved from Herzing University; Herzing University: Akron, OH, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, J.P. Student Perceptions of School Climate: Relations with Academic Achievement and Behavioral Adjustment. J. Sch. Psychol. 2012, 50, 707–720. [Google Scholar]

- Samiee, S.; Chirapanda, S. International Marketing Strategy in Emerging-Market Exporting Firms. J. Int. Mark. 2019, 27, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chabowski, B.R.; Mena, J.A. The structure of international marketing capabilities. An analysis of its antecedents and performance outcomes. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 42, 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- Chabowski, B.R.; Mena, J.A. A review of global competitiveness research. Past advances and future directions. J. Int. Mark. 2017, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carnahan, S. Generalized Moonshine IV: Monstrous Lie Algebras. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1208.6254. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.; Lim, K.H. The cross-platform synergy of social media. An empirical study of the effects of website and social media integration on brand relationships. J. Advert. Res. 2012, 52, 443–457. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C.; Kuester, S.; Krohmer, H. Marketing Management: A Contemporary Perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 46, 306–308. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, J.; Botten, N. Marketing Strategies. A Twenty-First Century Approach; Pearson Education: Hong Kong, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, E.L.; Roth, A.V.; Fensterseifer, J.E. Organizational knowledge and the manufacturing strategy process. A resource-based view analysis. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, A.R.; Quintella, R.H. The role of internal and external factors in the performance of Brazilian companies and its evolution between 1990 and 2003. BAR Braz. Adm. Rev. 2006, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Schroeder, R. Dimensions of Competitive Priorities. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2011, 18, 77–86. [Google Scholar]