1. Introduction

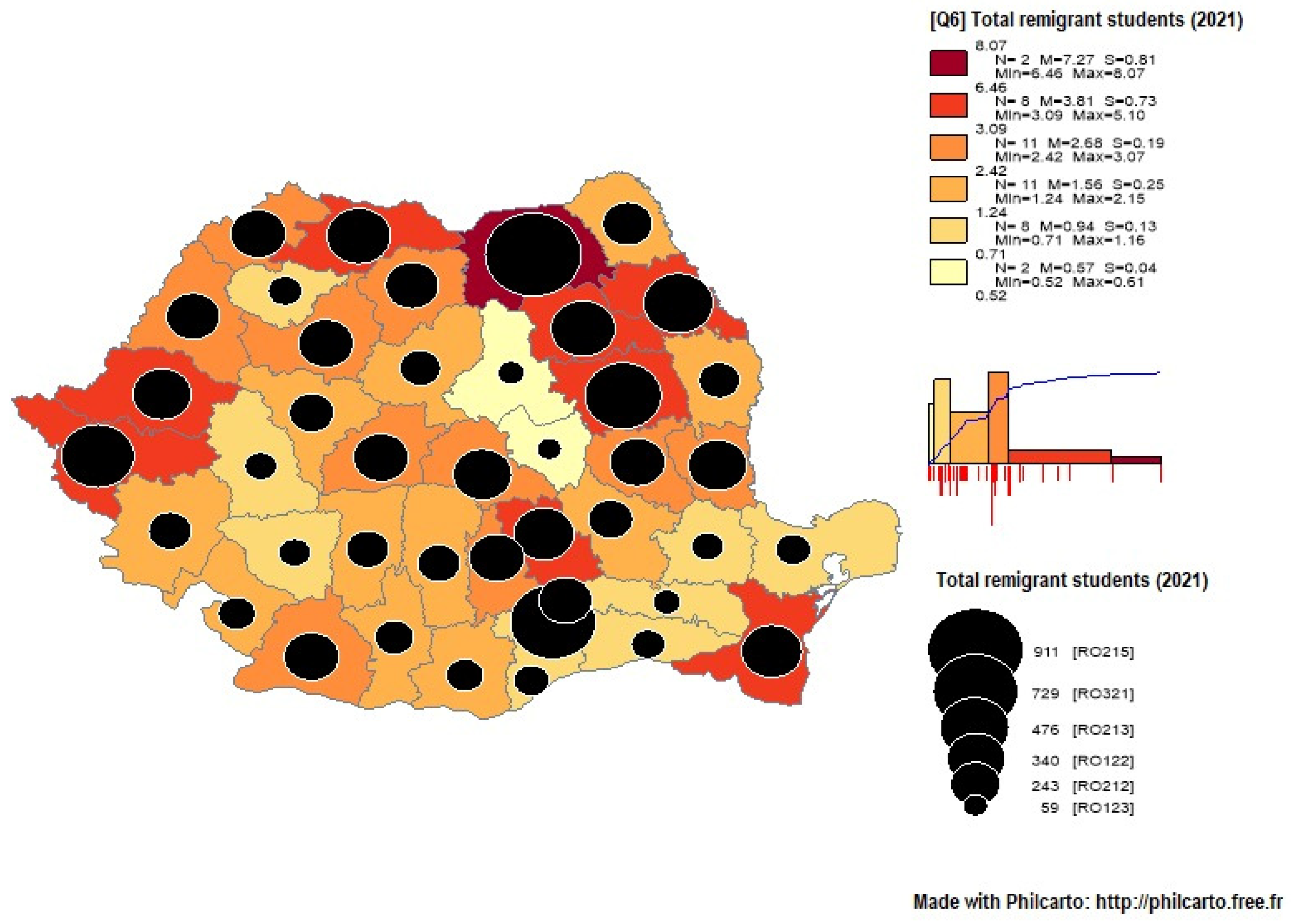

The economic crisis in 2009 and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, have brought about significant changes in the international migration of Romanians, both in terms of migration flows and in the behavior of migrants. In this context, an increasingly visible trend is remigration—the process of Romanian citizens returning to their country after a period spent abroad. Health restrictions, job uncertainties, and the desire for stability have led many Romanian families to return, either temporarily or permanently. A particularly important aspect of this phenomenon is its impact on children and teenagers. Data provided by the Ministry of National Education shows that in the first 2 years of the pandemic (2020 and 2021), more than 20,921 students were integrated into the Romanian education system, following the application for certificates of equivalence of studies. In particular, the North-East Region of Romania—known for its high level of economic emigration after 1990—recorded the highest number of remigrant pupils at a national level (24.3% of the total). Within this region, the county of Suceava is the one with the highest number of pupils (911) returning from abroad in 2021 (33% of students returning to North-East Region and 8.7% of students returning to Romania) (

Figure 1). This is the reason why, in our study, we have chosen to analyse the perception of teachers in the North-East Region and proportionally, most questionnaires were distributed and filled in Suceava county. Without being representative for the country as a whole or for return migration, our study may constitute a case study that introduces as a novel element the analysis of this phenomenon from the teachers’ perspective.

1.1. Literature Review

Previous migration studies have predominantly focused on adults, and research addressing the impact of remigration on children is relatively limited [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The involvement of children in the decision-making process of the remigrating family and the lived experiences of return [

4], are rather under-researched topics, given the lack of research on the role of children in family migration in general [

5].

Remigration is a complex process that can profoundly influence the emotional, social, and educational development of children and graduates. Studies show that for some children, this experience is a major source of stress and vulnerability, with negative consequences for psychological and relational well-being [

6]. For this reason, the mental health of remigrant children has been intensively studied [

7,

8,

9], and the results of the research are contradictory. On the one hand, some studies suggest that the mental state of migrant children is more fragile than that of non-migrant children [

7,

8,

10,

11]. On the other hand, other research contradicts this idea, showing good psychosocial adjustment among remigrant children. For example, Hatzichristou and Hopf [

12] found that although Greek children returning from Germany experienced difficulties in school performance, they did not show significant interpersonal or intrapersonal problems compared to their peers. The support of the Greek community and strong cultural identity were key factors in their adaptation, which made the difference to the Turkish migrant children in Germany. Moreover, some studies even suggest that migrants may have a better mental state than their native peers [

13,

14]. For example, children of Chinese, Japanese or South-East Asian origin showed fewer behavioral and adjustment problems than children of native parents. These differences may be explained by the different ability to cope with stress, which depends on both individual factors and support from family, school, and community [

15,

16,

17].

Another important factor in the adaptation process is the age of remigrant children. Studies show that the younger children are at the time of remigration, the easier they adapt and the better they do at school [

12,

18]. Conversely, multiple or prolonged migration experiences may increase the risk of anxiety and depression [

8]. Cultural differences also play a significant role: the greater the cultural differences, the greater the adaptive stress [

19]. Thus, the impact of remigration on children and adolescents varies according to a number of individual, family, and social factors. Understanding these variables is essential in order to provide adequate support and facilitate their integration into their new environment.

In Romania, research on this phenomenon is relatively scarce but relevant. Previous studies have focused on the problems of functional illiteracy among remigrant children [

20], their specific educational needs. [

21,

22], and on the social image of the remigrant child [

23].

However, the teachers’ perspective on this process is insufficiently explored. This study aims to fill this gap by analyzing the perceptions of teachers in the North-East Region of Romania regarding the educational challenges and opportunities of remigrant children. In contrast to existing research, which has focused on the direct experiences of children or parents, this study brings to the forefront the opinion of teachers, providing an essential insight into how these pupils integrate into the Romanian educational system.

1.2. Return Migration of Romanian Children and Adolescents and Educational Resilience

The concept of resilience is based on the idea that a stressful situation or adversity in life affects individuals differently, with some being vulnerable to stress while others developing the capacity to cope more easily. Therefore, resilience translates into individual responses to a particular type of risk [

15,

16,

24,

25], and it is specific to individuals who, in the face of certain adversities, develop normally and remain mentally healthy. Resilience is a dynamic process that entails change, depending on certain circumstances [

26,

27]; it can be defined as the capacity or result of successful adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances [

28]. Resilience is achieved not by avoiding stress [

24] but by managing it effectively, by developing secure and stable affective relationships. It presupposes a favourable environment that will provide the individual with increased self-confidence and community integration.

According to the literature, the concept of educational resilience has been defined as the likelihood of achieving academic performance and the ability to cope with the challenges and pressures of the school environment, despite vulnerabilities determined by personal factors and environmental factors and experiences [

29,

30,

31]. Educational resilience is seen not as a fixed attribute, but rather as a characteristic that can be developed, by accessing personal, family, and institutional resources, and that has a major impact on the adaptation and school success of remigrant students [

32,

33]. The authors of representative models of educational resilience [

34,

35] have identified four broad categories of protective factors—personal, family, school, and community—that ensure school success for at-risk students.

The main objective of the research is to investigate the effects of remigration on children’s school adaptation, with a focus on learning difficulties, relationships with peers and teachers, and level of Romanian language proficiency. The study also explores the factors that contribute to the development of educational resilience and the impact of family, school, and community support on the integration process.

The research we conducted is based on teachers’ perceptions of migrant pupils’ behaviour, their understanding of their situation, their ability to process their experience, and integrate it into their system

This study aims to answer several questions in order to finally paint a picture of the remigration of Romanian children and their educational resilience:

- -

What are the main challenges faced by Romanian migrant children from the perspective of the teaching staff they interact with?

- -

What is the perception of teachers about the relationship difficulties of Romanian migrant pupils?

- -

Is the (re)integration of remigrant children an opportunity that could be used by schools to cultivate values and attitudes in native pupils?

- -

What factors contribute to the development of educational resilience among migrant children?

- -

How do Romanian teachers perceive the role of Romanian language proficiency in the reintegration of remigrant pupils?

In order to decipher the characteristics of remigration and the educational resilience of Romanian remigrant pupils, we started from the following hypotheses:

H1: Some of the Romanian remigrant children face problems related to the acquisition of knowledge and show some behavioral problems (attention deficit, apathy, sadness) and relationship problems (isolation, marginalization by others).

H2 : The resilience of remigrant children is an opportunity for teachers to cultivate a set of values and attitudes such as tolerance, responsibility, and ambition among native pupils.

H3: The level of educational resilience of remigrant children is positively influenced by family support in the school reintegration process and differs according to the age of the remigrant children.

H4: Romanian language proficiency of remigrant children is a significant predictor of successful educational integration.

2. Materials and Methods

This study utilised data that were collected through an online survey conducted between July 2023 and February 2024, among teachers who have worked with remigrant students who have had their studies equated in the last 5 years

Data collection was made through an online, self-administered questionnaire designed and hosted on a dedicated platform. The link to access the questionnaire was forwarded to potential respondents, teachers in the six counties of the North-East Region, who teach in primary, secondary, and high school. The reason for choosing the topic and region of the study is based on the fact that the North-East Region of Romania is characterised by the highest rate of impoverishment in the country, the highest rate of emigration after 1990, but also by the highest number of remigrant pupils registered in 2021–2022, which represents almost a quarter of the total number of remigrant pupils registered in Romania (24.3%) [

36].

We consider that a deep knowledge of the issues related to the school integration of remigrant pupils and their adaptation to the new learning context, respectively to the new social context in which they live, involves at least the following perspectives:

Knowledge and understanding of issues related to the integration of migrant pupils from the perspective of the migrant pupil’s family of origin and extended family.

Deepening of the views expressed by remigrant pupils on the challenges they are faced in the new social and learning context. This perspective would require a mixed methodological approach that could equally integrate pupil opinion instruments, qualitative studies carried out using interview tools, or even group interviews, and, last but not least, the application of participatory observation tools at the level of the pupil classes and groups of friends.

The perspective of teachers who interact on a regular basis with pupils who have had migration experiences.

From a methodological point of view, we appreciate that the research approach is exploratory, centred on the inventory of perceptions expressed by the teachers participating in the study, which leads us to consider that our approach should be understood as a pilot project that will allow us to better understand this topic. The sample was constructed by the snowball method; all participants were asked to send the link to the questionnaire to other teachers known to us in order to increase the number of participants. Without claiming that the validated sample is statistically representative, we believe that the opinions expressed reflect and allow a good understanding of the problems of migrant pupils.

All study participants were informed about the purpose of the study and that their answers will be used for scientific research purposes.

The data-collection instrument was constructed in the form of a sociological questionnaire consisted of a total of 32 questions, most of which were questions with predefined answers. In constructing the questionnaire used, we focused on operationalising the following dimensions:

for the dimension of causes/factors that led pupils and their families to remigrate—seven items were formulated that captured teachers’ perceptions of aspects/factors that might have contributed to the remigration decision of pupils and their families. Each item was measured by a Likert scale, in four steps (we chose an odd number of measurement steps to avoid the tendency of respondents to give answers covering a neutral zone of opinions), 1—to a very small extent, respectively 4—to a very large extent. In order to test the internal consistency of this dimension, we used the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. After eliminating two redundant items (a bad financial situation and lack of a secure job in the country of emigration), internal consistency is given by a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.57.

for the learning process dimension, six items were formulated in order to capture teachers’ perceptions of the learning process of remigrant pupils. For each item, teachers’ perceptions were measured by means of a four-step Likert-type scale, where 1—to a very small extent, respectively 4—to a very large extent. In order to test the internal consistency of this dimension, Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was calculated. After eliminating two redundant items (they had a higher level of training, and we did not notice any differences), we obtained a scale with internal consistency for good (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.87).

for the dimension of pupils’ social interactions, eight items were formulated which focussed on teachers’ perceptions of migrant pupils’ relationships with classmates or with other pupils who have had a migration experience or even with family members. Also in this case, the scale used to measure the intensity of opinions was a Likert type with four steps, where 1—to a very small extent, respectively 4—to a very large extent. The projected scale has very good internal consistency, given by a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.79.

the dimension of remigrant pupils’ adaptation was captured through 10 distinct items. The teachers participating in the study had the opportunity to express their opinions through the 10 items, which were measured by a Likert-type scale (similar to the previous dimensions), where 1—to a very small extent, respectively 4—to a very large extent. The internal consistency analysis is judged to be very good, Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.90.

In order to capture the teachers’ representation of the remigrant pupils with whom they interact, we opted for the use of an open-ended question asking respondents to mention four words that could summarise this aspect. The attributes mentioned were grouped according to the dimension they targeted, resulting in three distinct dimensions: attributes that emphasise the acquisition of knowledge and the formation of skills and abilities; attributes that express integration, interpersonal, and collaborative skills; and a third category of attributes that express complex psychological capacities and traits: attitudinal, motivational, affective. For each of these three categories of attributes, positive meanings and negative connotations were inventoried.

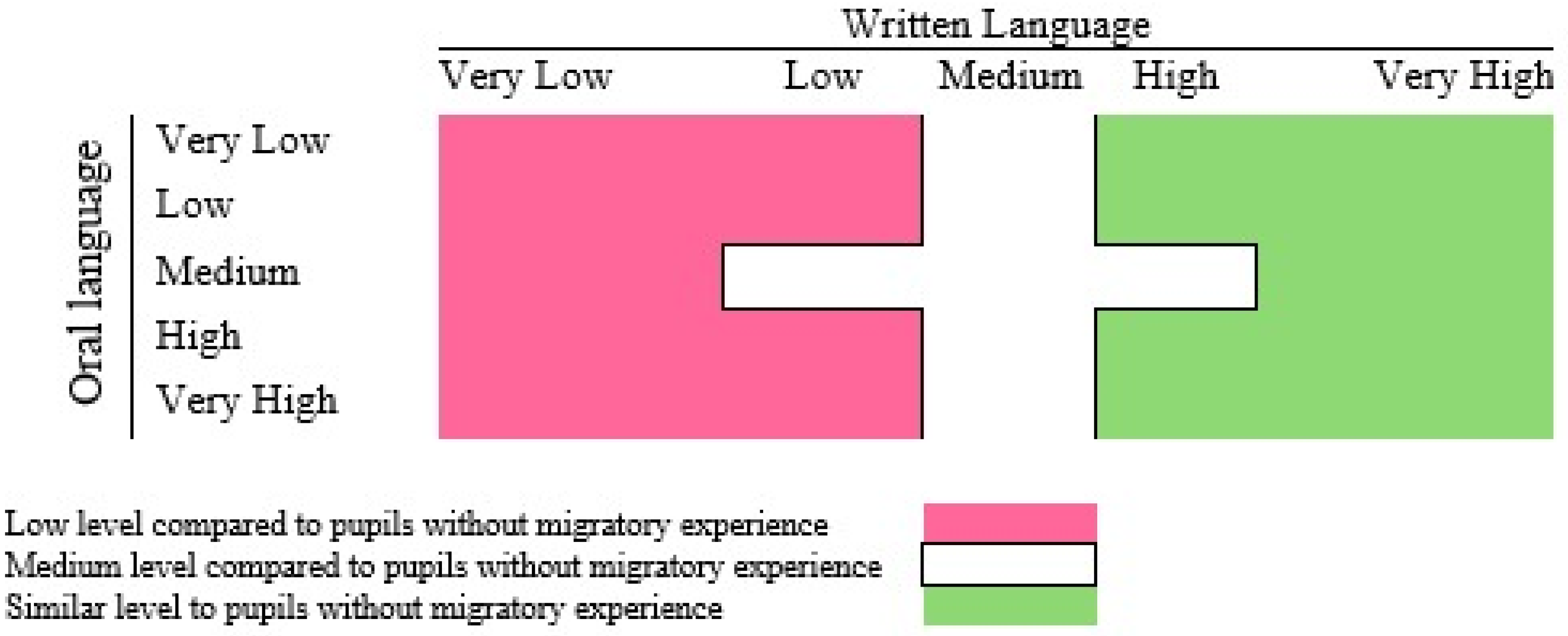

The aspects related to Romanian language proficiency were surveyed by using two separate items that focused on aspects related to the use of Romanian language in speaking and reading, respectively in the form of written Romanian language use. For each of these dimensions, the teachers had the opportunity to assess how these aspects were manifested among the remigrant pupils. For this purpose, we used a Likert-type scale with five steps (

Figure 2), where 1—very low level and 5—very high (similar to the level of the other pupils). As a result of the aggregation of the response variants, we obtained three levels of knowledge and use of the Romanian language as follows:

Complementary to the operationalised dimensions, information was also collected on teachers’ perceptions of the behaviour of remigrant pupils, their understanding of their situation, and their ability to understand their experience and to integrate it into their belief system. It also addressed issues related to the effective management of the stress generated by remigration, the development of affective relationships at school and in the family, and the development of a favourable environment for the development of remigrant children, which gives them increased self-esteem, self-confidence, and motivation for learning as basic prerequisites for adaptation at school and in the community.

We mention that the instrument used in this research (the questionnaire distributed to teachers) was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of “Stefan cel Mare” University of Suceava, Romania, no. 143 of 22 June 2023.

The initial number of teachers who participated in the study was 643, but after the validation process of the responses a total of 500 teachers were selected to make up the sample of the present study. The distribution of the study participants by gender reflects the feminised structure of the teaching profession as follows: 84.8% were female respondents and 15.2% were male respondents. It should be noted that the variable “gender of the respondents” did not influence the results of the research carried out, given that the teaching profession in general shows a high tendency towards feminisation, and the variable “gender” was not included in the statistical analyses carried out. The average age of the participants in the study was 44.7 years, and the distribution by environment reveals a higher number of participants from urban areas (60.2%) and a lower number from rural areas (39.8%). We note that the distribution of teachers participating in the study according to the specific educational level at which they carry out their teaching activity is relatively balanced, as follows: pre-school and primary education—35.4%, secondary education—30.6%, and high school education—34%.

3. Results

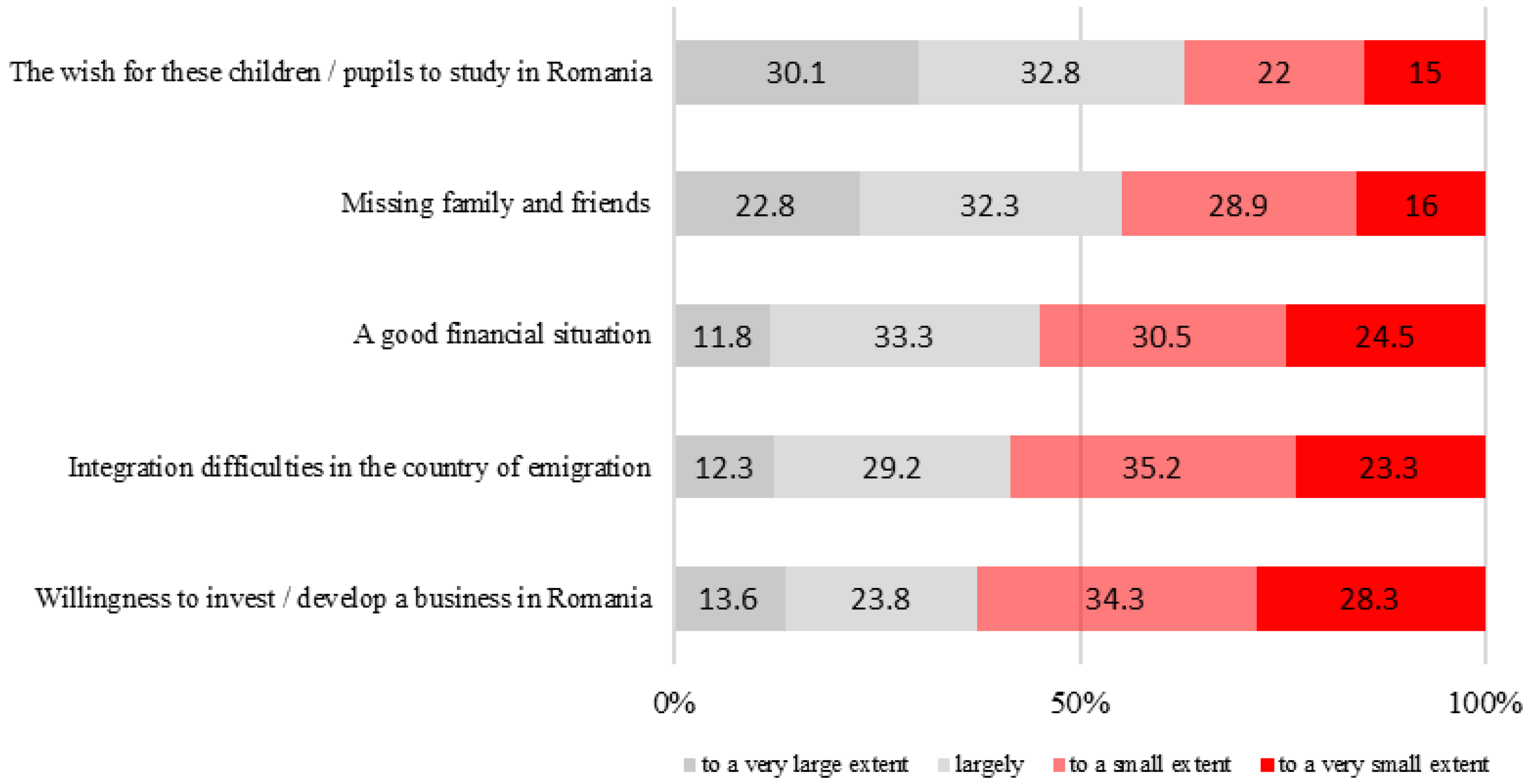

In most cases, remigration is the result of a family decision, especially of parents with school-age children who wish to enrol or re-enrol them in the Romanian education system, which they perceive as more comfortable and friendly. According to teachers’ opinion, the main reason of families with children that return to Romania partially or totally is the parents’ wish to offer their children an education in Romania (

Figure 3). Thus, almost two-thirds of the teachers surveyed considered this to be one of the main or very important factors in their decision to return to Romania (62.9%).

From this perspective, it is important and useful to analyse how migrant children manage to integrate into the school environment, even though some of them have had no direct contact with their parents’ country.

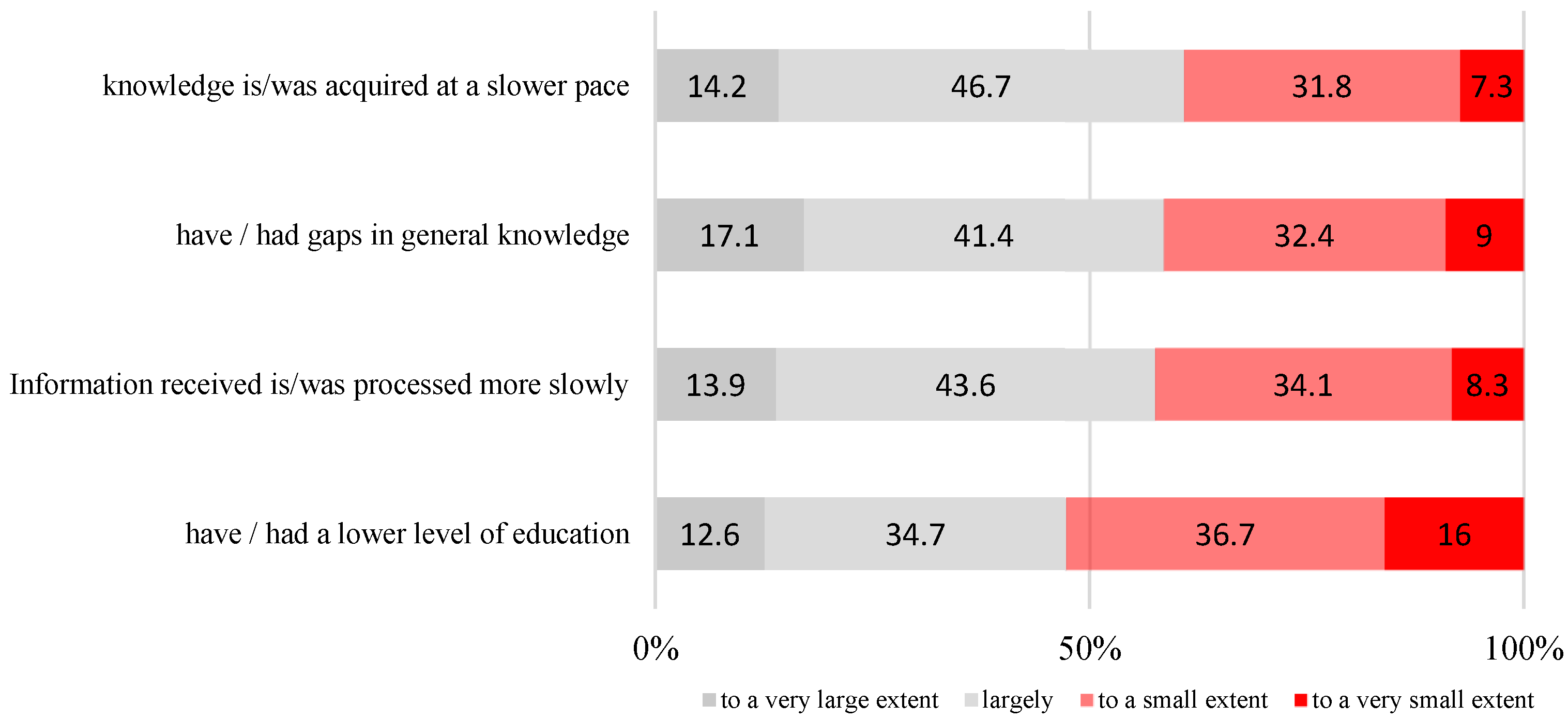

In terms of teachers’ perceptions of the difficulties faced by pupils from abroad, the most frequently mentioned difficulties are, as expected, those in the cognitive sphere (

Figure 4). More than 50% of the respondents believe that information is processed more slowly and more slowly by these children, that they have more gaps and even lower levels of preparation than native pupils. Analysing the results related to the perceptions of the participants in the study, we find that the opinions expressed are almost similar regardless of the level of the study programmes (pre-school and primary, secondary or high school).

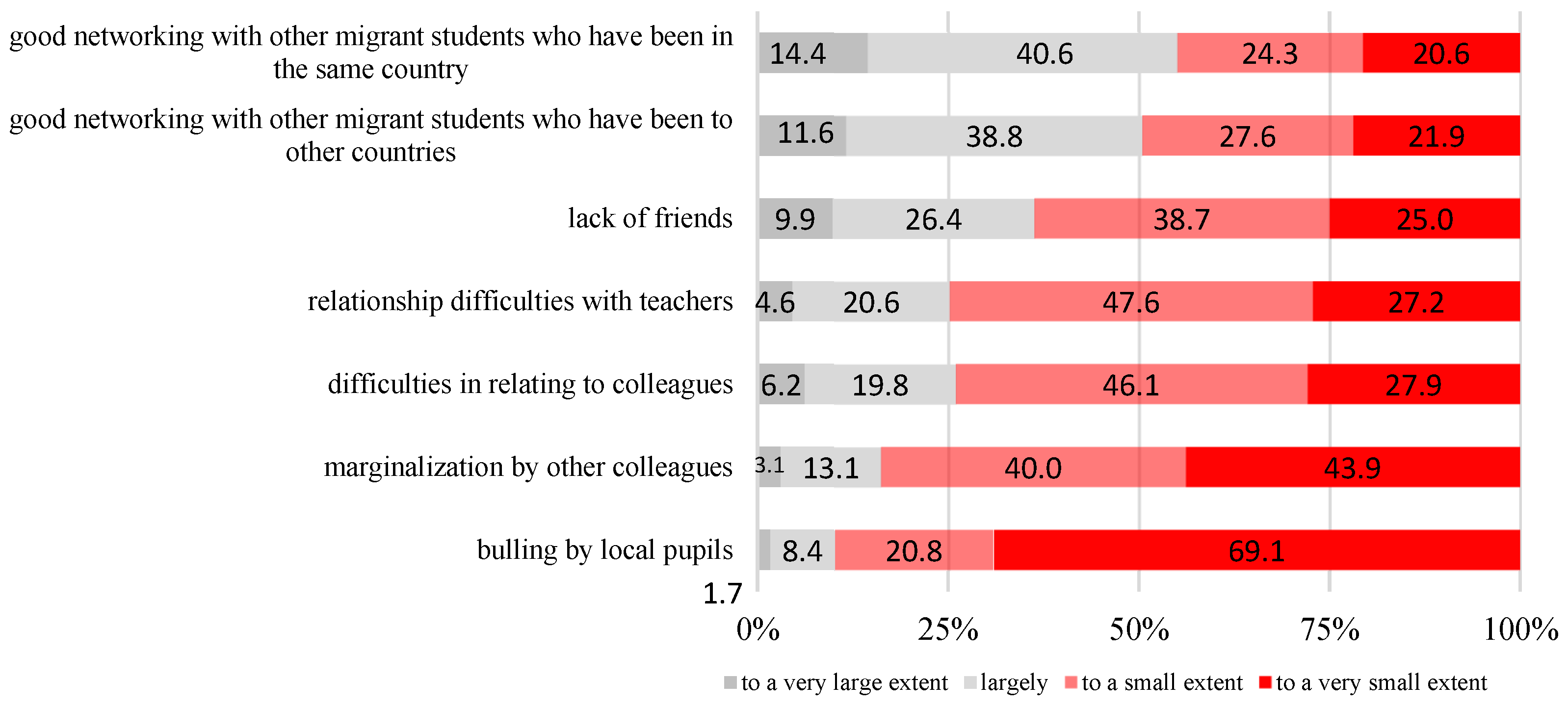

In terms of interactions with teachers and classmates in terms of developing collegial or even age-specific friendship relationships, teachers’ perceptions emphasise that remigrant pupils do not face major difficulties in terms of interactions specific to the educational environment. Thus, in the case of interaction with teachers or classmates, the perception of the teachers participating in the study highlighted that at most, 25% of the remigrant pupils might have interaction difficulties. When referring to the coagulation of friendly relationships with the peer group, teachers estimate that the share of problematic interaction situations might affect more than one-third of the pupils (36.3%)—(

Figure 5). Although interactions with peers do not seem to be problematic, the teachers participating in the study noted the existence of situations of marginalisation of remigrant pupils (16%), who sometimes may even face bullying situations (about 10% of the teachers estimate that remigrant pupils are targets of bullying/bullying activities).

At the opposite pole, the teachers participating in the study emphasise a better level of relationship of remigrant pupils with peers who have experienced migration and remigration (especially with those who have been in the same country, with whom they may have at least the language of the country from which they have remigrated in common), and therefore with pupils who show a higher degree of empathy with the remigrant situation.

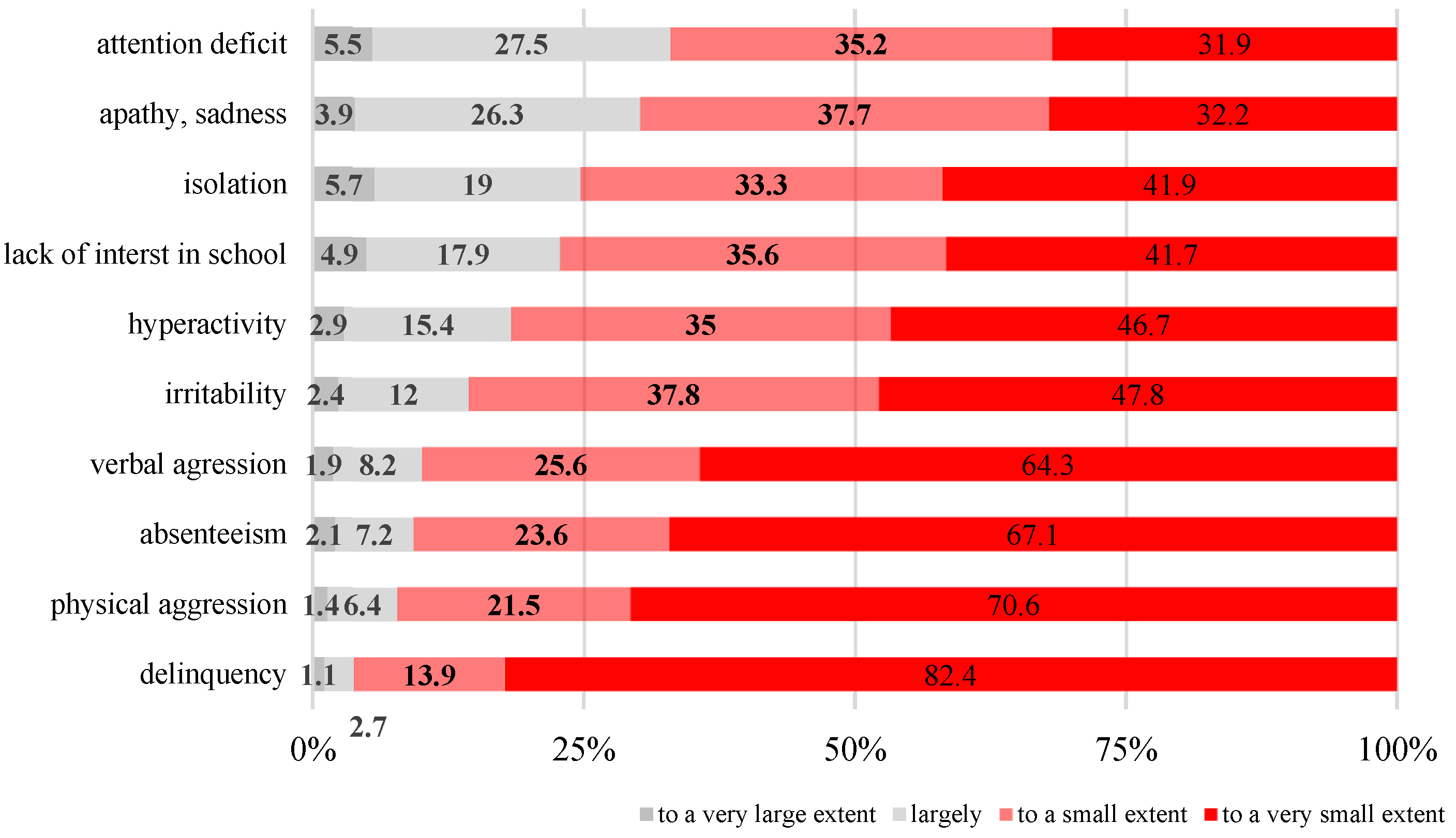

The analysis of the study participants’ opinions on the behaviors exhibited by remigrant students and how they have adapted to the new educational context was also a focus of our study (

Figure 6). Thus, about one-third of the teachers consider that remigrant students have a deficit of attention about the didactic activities in which they participate, a behavior that directly contributes to reinforcing their lack of interest in school (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.535,

p < 0.01).

From a behavioral point of view, we notice the tendency of teachers to appreciate that students who have a migratory experience show a type of apathy, non-involvement in educational activities, or even sadness, which may directly contribute to the emergence of isolation behaviors from the group (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.543, p < 0.01) and could highlight a low level of social integration in the group of students.

Although marginalizing behaviors were not reported to be highly present among remigrant students, the very strong correlation between verbal aggression and physical aggression is also confirmed (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.734, p < 0.01), the strong correlation between absenteeism and the odds of delinquent behavior (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.597, p < 0.01), between irritability and verbal aggressiveness (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.537, p < 0.01), and between irritability and physical aggressiveness (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.553, p < 0.01).

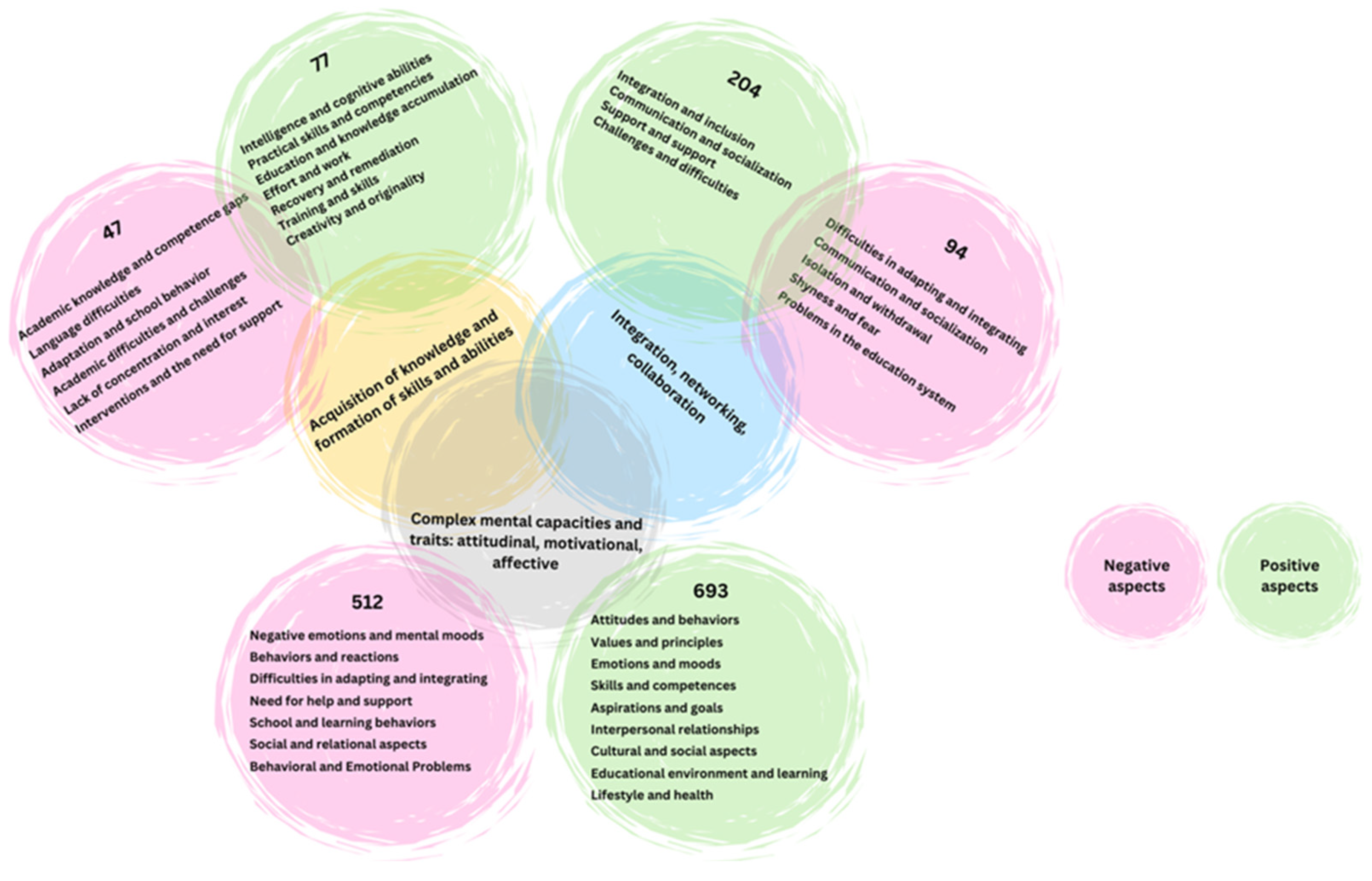

3.1. Teachers’ Perception of Migrant Pupils Summarized in a Few Words

In order to be able to outline teachers’ perceptions of remigrant pupils, participants in the study were asked to summarise in a few words the situation of remigrant pupils in their own opinion. Following this invitation, the 500 respondents listed 1663 attributes that were associated with this category of pupils. The inventoried attributes were grouped into three distinct categories as follows: attributes that emphasise the acquisition of knowledge and the formation of skills and competences; attributes that express integration, interpersonal and collaborative skills; and a third category of attributes that express complex psychological capacities and traits: attitudinal, motivational, affective.

For each of these three categories, attributes with positive and negative connotations were identified (

Figure 7).

The results obtained from the analysis of the teachers’ free responses indicate that the aspects related to pupils’ general behaviour and mood were most frequently mentioned. These aspects, which refer to complex psychological abilities and traits (motivational, attitudinal, affective), are followed in terms of frequency in the teachers’ answers by those concerning relationships and co-operation with others; last in terms of frequency of mentions are the aspects concerning knowledge acquisition. More than 1200 attributes in the category “Complex mental abilities and traits” were mentioned, compared with less than 150 in the category “Acquisition of knowledge and formation of skills and competences” and less than 300 in the category “Integration, interpersonal relations, co-operation”. Another important element emerging from the analysis of teachers’ open-ended responses is their predominantly positive perception of all three dimensions mentioned above (complex traits, interpersonal relations, knowledge acquisition) in relation to the returned pupils. The clearest positive perception can be seen in the category “Integration, relationships, co-operation”, where more than 68% of the attributes had a positive connotation, compared to 62% in the category “Knowledge acquisition and formation of skills and competences” and 57% in the category “Complex psychological abilities and traits: attitudinal, motivational, affective”.

More than 60% of the teachers who indicated an aspect related to their relationships with others had a positive mention. Adaptability and sociability of these children were mentioned most often, while shyness and a tendency to isolate were mentioned negatively. As for the complex psychological abilities and traits mentioned by the teachers, on the basis of the same predominantly positive perceptions, the most frequently mentioned aspects were curiosity, ambition, responsibility, but also emotional instability, disinterest, and isolation.

3.2. Family—A Determining Factor in Achieving Educational Resilience for Remigrant Pupils

An important role in the development of resilience mechanisms of remigrant pupils is played by the family as an element of emotional support and psychological security with a determining role for this category of pupils [

17].

The analysis of the results revealed that the teachers participating in the study give greater importance to the family in resolving the adjustment and integration difficulties of younger pupils. For example, by using the Kruskal–Wallis test we could observe that the role of the family in overcoming school adaptation and integration difficulties is perceived to be more important in the case of pupils attending pre-school and primary education compared to the way it is perceived in the case of migrant pupils attending secondary education H (2) = 32,821, p = 0.000.

The perceptions of the teachers participating in the study also revealed that the development of resilience behaviors of remigrant students may also be associated with how the family structure looks to these students (

Table 1). Thus, when they have remigrated together with the whole family (both parents), they are less likely to be subject to marginalization by the other pupils (χ

2 = 6.368 (df = 2),

p < 0.041); parents can be appreciated as a resource that provides remigrant pupils with security, trust, and a possible “protective shield” from other pupils.

Also, the perception of the teachers regarding the occurrence of behaviors that can be related to situations of violation of social norms and even criminal (delinquency) shows that the remigrant pupils who returned to the country with their parents are less likely to develop such behaviors (χ2 = 16.417 (df = 2), p < 0.00), the family implicitly also exerts the function of social control and supervision of the behaviors developed by the pupils.

The role of parents in overcoming the adjustment difficulties of remigrant pupils is also evidenced by an inversely proportional relationship of medium intensity between the level of parental concern and difficulties in relating to other family members who have not had migration experience (Kendall’s tau_b = −0.314, p = 0.00). This correlation highlights the fact that when the family of the remigrant pupils is concerned about how the children adapt, their integration difficulties are lessened, as the parents are the glue that binds the relationship between the children and the extended family, especially when the extended family has not had migration experiences and does not know the realities/language/concerns that the remigrant pupils have had in the communities/societies from which they have returned. In a similar way, it can be observed the existence of an inversely proportional relationship of medium intensity between parental concerns and family relationship difficulties (family atmosphere after remigration), Kendall’s tau_b = −0.3338, p = 0.00, respectively the directly proportional relationship between family concern and emotional/affective support provided by the family during the period of adaptation and integration of the pupils (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.335, p = 0.00).

Pupils’ resilience is developed through the family not only in the sphere of social interactions and the existing family climate, but it can also be observed in the school context. Thus, the opinion of the teachers participating in the study highlights that there is a statistically significant, inversely proportional relationship between family interest and the occurrence of behaviours such as attention deficit (Kendall’s tau_b = −0.317, p = 0.00), lack of interest in school (Kendall’s tau_b = −0.363, p = 0.00), or truancy (Kendall’s tau_b = −0.334, p = 0.00). In other words, when the family of remigrant pupils shows interest in the education, adaptation, and integration of the pupils in the school environment, risk of dysfunctional behaviours such as lack of attention to school activities, low interest in school, or absenteeism are increasingly reduced.

Of course, within the family “microsystem”, the importance of parental relationships is determinant, and the results show that self-confidence decreases with increasing difficulties in family relationships (Kendall’s tau_b = −0.211,

p = 0.00) and support the idea that the poorer the quality of parental relationships, the poorer the social integration of migrant children [

37]. In addition to the role of the nuclear family, the extended family, represented by grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins, has a determining role in the social integration of remigrant children. A very strong correlation has been identified between parental support/affection and relationships with other family members. Thus, the more visible the lack of parental support and lack of parental affection, the greater the difficulties in relating to other family members who have not had migration experiences (Kendall’s tau_b = 0.701,

p = 0.00). Some Romanian families returned ‘home’ precisely because of close family ties. Close ties with the family in the country of origin frequently contributed to reintegration, together with friends and acquaintances of the remigrant parents. These ties work by developing a sense of belonging to the place of origin, a sense of belonging through co-participation in everyday realities, and thus build social capital for both the migrant children and their parents [

4]. If this level fails to provide protection, another level represented by community support services, namely the exosystem, has a key role to play. The association between the educational level and the activities carried out by school units with the aim of facilitating the integration of remigrant children/students revealed that meetings with the school psychologist are specific to secondary schooling, unlike previous schooling levels (χ

2 = 41.355 (df = 2),

p < 0.000).

Alongside the level of Romanian language proficiency, which is a key factor in achieving educational resilience, the teachers surveyed consider that support from the school and the family, as well as a number of personal characteristics of the pupils (self-confidence, high self-esteem, and strong motivation for learning) play an important role in the process of educational resilience.

3.3. The Importance of Language Proficiency in Teaching and Learning

The results of the study emphasise that, according to the teachers, certain psycho-emotional characteristics of pupils may be influenced by their level of knowledge of Romanian (reading and writing). Thus, according to the teachers’ perception, remigrant pupils who have a similar level of language proficiency as pupils without migratory experience show a high level of self-confidence, are motivated to achieve their goals, and have high self-esteem. In contrast, a low level of Romanian language proficiency contributes to low values of the listed personal characteristics (

Table 2).

It is obvious that a low level of language proficiency makes it difficult to understand the concepts taught and considerably hinders the acquisition of new knowledge and the formation of practical skills and attitudes, which, among other things, are the basis for adaptation and success at school. Difficulties in assimilating knowledge lead to poor and mediocre school results, which negatively impact self-esteem and self-confidence, and reduce the intrinsic motivation for learning.

The obtained results reveal that in the opinion of the teachers, a low level of Romanian language proficiency negatively influences not only the teaching and school performance, but also the personal behavioral characteristics of the remigrant pupils, which may generate negative consequences in the psycho-emotional and adaptation plan. The teachers participating in the study consider that a low level of knowledge of the Romanian language (

Table 3) may contribute to an increase in the attention deficit of the pupils, to the lack of interest in school, to the appearance of isolation, apathy, sadness and, implicitly, to the decrease in interactions with other colleagues. All these behavioral elements specific to remigrating pupils can generate frustrations and behaviors that manifest themselves either in aggression and violence or in anxious and withdrawn behavior.

In the perception of teachers, low and medium levels of Romanian language proficiency have an impact on the communication ability of remigrant pupils and may affect their ability to relate to both peers and teachers. The analysis of the results revealed that the participants in the study considered that a low level of proficiency in the language of teaching and learning affects the relationships with teachers (χ2 = 11.23 (df = 2), p < 0.004), with peers (χ2 = 16.16 (df = 2), p < 0.000), and can contribute to the strengthening of friendly relationships (χ2 = 13.82 (df = 2), p < 0.001). As expected, teachers noted that when remi-grant students interact with other peers who have experienced migration and remigra-tion (in the same country), the low level of the language of teaching-learning does not affect the quality of the interaction between the students, as they communicate (most likely) in the language of the country from which they remigrated to Romania.

4. Discussion

Remigration is a complex phenomenon, which in most cases involves the stress of moving to a new culture and reintegration difficulties, especially for children and adolescents [

38] who are placed in a foreign or unfamiliar environment where people, customs, and sometimes even the language, are different from those in the country where they lived before remigration. Although readjustment can also be difficult for adults, they have identities more strongly anchored in their place of origin, which makes reintegration easier [

39]. The successful integration of pupils in the country of remigration depends on their adaptation to the new school environment and new educational requirements. They go through a period of adjustment in which everything is unknown: the new school, the new group of pupils, the teachers.

According to the results obtained through our study, most of the remigrant children seem to have proved to be resilient from the perspective of their teachers, successfully adapting to the Romanian school environment. However, for one-third of the returnees, the teachers noted difficulties of adaptation related either to the acquisition of knowledge, to their relationships with others, or to their psycho-emotional state. From the teachers’ point of view, the most important factors that made the difference between the resilient and the maladjusted were the family, the level of knowledge of the Romanian language, and the support offered by the school (for the older ones). The teachers’ perception of the returnee children is predominantly positive; the teachers have noticed in these children skills and values that they could also cultivate among the native children. However, this positive perception does not preclude the observation of negative behaviour among the returnees, which sometimes underlies the difficulties they are faced with.

Our study shows that, at least in the opinion of the teachers with whom remigrant children interact, there are many problems that these children have to face. We consider that the fact that more than 50% of the teachers participating in the study noted difficulties in the acquisition of knowledge and the general level of preparation of remigrant pupils, as well as the fact that more than one-third of the respondents noted that these children had difficulty in relating to others and a problematic behavior expressed by apathy, sadness, and isolation, confirms the first hypothesis of our study; the results of the analysis of the respondents’ free answers lead to the same confirmation, with between 30 and 40% of these answers indicating negative attributes for all three aspects considered. Thus, the results of our study are in agreement with those obtained in similar studies carried out either for Romania [

22,

40] or for other countries [

41,

42]. The difficulties faced by remigrant children may be a prerequisite for the emergence of behavioural disorders, as some studies have already mentioned [

24]. It should also be mentioned, however, that only one-third of the teachers mentioned various problematic aspects that they had noticed in children who had returned home after a migration experience. This percentage (30%) correlates with the results of the study conducted by Luca et al. [

21], according to which 30% of the children returned to Romania are at significant risk of developing adjustment difficulties.

We believe that the second hypothesis of the study was confirmed by the results of analysing teachers’ free responses related to the characteristics of remigrant children. The fact that more than 60% of the responding teachers mentioned positive aspects related to remigrant pupils in all three dimensions (knowledge acquisition, integration, interpersonal, relational, collaborative, and complex psychological traits) and the fact that more than 60% of the mentioned attributes had positive connotations on all three dimensions are arguments for the confirmation of the second hypothesis of our study. The results obtained are also confirmed by studies in the field, which claim that the mental state of migrant children is more fragile than that of non-migrant children [

10,

19,

21], but also studies indicating fewer conduct disorders than natives and a good psychosocial adjustment of remigrant children [

12,

14,

43], or even a better mental status of migrants compared to their native peers [

13].

The transactional model, developed by Cicchetti & Toth [

44], is based on the idea that there is a complex of factors, biological, emotional, cognitive, linguistic, and representational, which interrelate, the child is not only influenced by the environment, but the environment is also influenced by the child. According to the ecological-transactional model, an individual’s environment is seen as composed of several co-existing layers that vary with respect to the individual in a hierarchical order from proximal to distal [

44,

45]. Thus, risk, protective, and vulnerability factors as factors influencing children belong to these levels and influence one another. The school, peers, neighbourhood or locality, services, and other formal and informal support systems make up the environment in which the child lives, and which has a determining role in the adjustment of migrant children and adolescents. The influence of personal factors, such as self-esteem, self-confidence, and motivation to learn, is decisive in school adjustment [

35].

The results of our study indicate that parents and family are the main support in the integration of remigrant children, which partially confirms the third hypothesis of our study, being in agreement with the results obtained by other studies on this topic [

4,

44]. According to Cicchetti & Toth [

44], family, friends, and other close people form the level with the strongest influence, this ‘microsystem’ providing support or, in some cases, adversity. Return migration is often associated with the process of returning to one’s own culture, family, and home (IOM, 2019) [

46], with the pain of separation from family and country being a constant in adult remigration [

47,

48,

49]. On the other hand, it was not possible to establish a link between the age of the remigrant children and their ability to adapt, and as far as the involvement of the school is concerned, teachers only mentioned a positive effect of the school counsellor’s intervention at secondary school level. It also turned out that the role of the family in facilitating the reintegration of remigrant children is nuanced by their age—younger children receive more support from their parents, which makes their reintegration easier. Thus, it can be said that the third hypothesis of our study is partially confirmed. Our study does not clearly confirm the importance of the age of remigrating children for their resilience, as do studies that have addressed similar topics [

12,

18,

50] according to which the younger the age of remigration, the fewer difficulties these children are faced with. This may, in our case, be the effect of analysing the phenomenon indirectly, through teachers who tend to compare the children they work with one another rather than with children in other age groups.

The fact that many students were born, lived, and studied in another country explains the low level of Romanian language proficiency. Difficulties in comprehension and, in particular, in writing, are major risk factors for remigrant children who become vulnerable to school maladjustment and educational resilience. The results also showed the existence of a correlation between the level of Romanian language proficiency and certain behavioural problems specific to these children, thus confirming the fourth hypothesis of our study. The importance of language knowledge level of the remigration country is also mentioned in the studies analysing the phenomenon in other countries. Thus, Hatzichristou & Hopf [

12] found that the age of return, the length of stay in Greece “after remigration” and language proficiency are critical factors related to the nature and severity of children’s difficulties” in the reintegration process, and Toukomaa [

51] found the importance of Finnish language proficiency in the school reintegration of Finnish children returning from Sweden. Korkiasaari [

52] has also emphasised the importance of knowledge of Finnish by remigrant children, the latter showing that almost all studies have shown poorer school performance (especially in the mother tongue) among remigrants.

Obviously, the results of this study must be seen in the context of some limitations imposed by the methodology used. The fact that the problems of remigrant children are identified and analysed through teachers’ perceptions is the main limitation of this study. There is a possibility that teachers’ perceptions are influenced by personal characteristics (age, professional experience), resistance to change generated by the interaction with pupils who have attended other education systems, with different habits, habits or styles of learning, and interacting with teachers and peers. The unequal distribution of the respondent teachers according to their residence environment may also be a limitation of the study; the fact that the predominance of urban respondents may give a less accurate picture of the reality of these children; in the Romanian space there are still important differences between the two residence environments from a sociocultural point of view, differences that may also generate different problems for these children.

Limits

This study has an exploratory design and aims to investigate a relatively new and understudied phenomenon in Romania. It highlights some aspects related to remigrant pupils’ vulnerability and educational resilience, opening new directions for further research.

From a methodological point of view, the present study might have some limitations concerning the sampling method. Thus, being aware of the debates generated by the selection of respondents using a snowball sampling method, we opted for this solution due to the fact that we did not identify an official data source that would allow us to identify teachers who, in their professional activity, interacted with pupils who had migratory experiences and returned with their families to Romania.

At the same time, due to the method used to select study participants, we were able to overcome possible reluctance of respondents to participate in the diagnosis. When the invitation to participate in such a study comes from a person known by the respondent, who instils confidence in the respondent, the chances of participation in the study can be improved, while at the same time the answers are clearer, more realistic, and more accurately reflect the opinions shared. We are aware that the bias generated by this type of sampling method could be a limitation of the study, but we consider it to be the most appropriate solution for collecting responses from the study participants.

An important methodological limitation was the absence of remigrant pupils in some classes, which could have influenced the overall perception of teachers. Thus, teachers who did not interact directly with remigrant pupils would have relied on indirect opinions or assumptions, which could affect the accuracy and relevance of the findings. This is the reason that led us to eliminate a significant number of questionnaires (143).

In order to eliminate ethical and confidentiality issues regarding data protection and informed consent, we have chosen to analyse only teachers’ perceptions of remigrant pupils’ behaviour, and in a future study we will focus on qualitative interviews with remigrant pupils and their parents.

Without claiming that the size of the validated sample (500 respondents) is statistically representative, we appreciate that the opinions expressed by the teachers participating in the study contribute to a better understanding of the issue of remigrant pupils and cover the perspective of teachers’ perceptions of this new reality of Romanian education.

5. Conclusions

Remigration therefore has different meanings for adults and their children, especially if the children were born in the country of emigration or have lived an important period of their lives and have built their identity in relation to the culture of that country. In the perception of these children, Romania is the country of their parents and not their own country, which leads to problems of educational and social integration, correlated, in some cases, with the rejection of their parents’ culture. If for their parents remigration has meant returning ‘home’, for their children Romania can be a foreign country in which they have no ties, especially if they have difficulty in speaking and writing Romanian. Thus, two different cultures, that of the parents and that of the children, sometimes coexist in the same family, and the adaptation of remigrant children in Romania can be an extremely difficult process which entails high psychosocial costs, with a major impact on their well-being and school performance.

At the same time, however, not all children who return to their own or their parents’ country after a short or long migratory experience find it difficult to reintegrate. Depending on the age at which they return, the structure of the family they return to, their personal characteristics, and the support they receive from their family and the community (the school being part of the community), reintegration can be a success or a failure. A good knowledge of the Romanian language (which is a result of the family’s concern to maintain the children’s links with the cultural environment in which the extended family lives and demonstrates that important links with the Romanian community in the country of emigration have also been maintained) contributes significantly to the successful reintegration of the children of remigrants. Through the skills and competences acquired in a different cultural environment, they can even become role models for local children and can provide a prerequisite for promoting values such as diversity, tolerance, multiculturalism, and mutual help through living, real-life examples.

By offering teachers’ perspectives on remigrant children, this study brings a new way of approaching the phenomenon of remigration. The teachers represent a lens through which the issues of remigrant children can be viewed in a more objective way than parents would provide. At the same time, teachers are able to observe and realise from the outside aspects that neither parents and sometimes nor even children (especially the younger ones) can perceive. By complementing this perspective, in future studies, with those on the children as the main actors, their parents and possibly their native peers/friends, a more complete and complex picture of the educational resilience of remigrant children can be built up.