1. Introduction

Farmers, the backbone of agricultural development, ensure that farm products are readily available for consumption and export when needed. Their decisions, influenced by the information disseminated through agricultural programmes, significantly impact their productivity [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Given the critical nature of agricultural information, access to this knowledge is paramount for agricultural development. Therefore, bringing issues related to the entire spectrum of agriculture into the limelight is imperative. This assertion is supported by the FAO [

5]. They argued that for success in the agricultural sector, efforts must be diversified beyond material inputs and human resources to improve knowledge and ready information at all stages of the agricultural production chain. With its unparalleled reach and influence, the media plays a pivotal role in disseminating information about all aspects of agriculture to farmers, enlightening them and making them aware of the significance of this information in enhancing agricultural development.

Radio can easily reach diverse audiences across the globe as a universal medium through its programmes. Adams [

6] supported this when he opined that radio programmes could reach individuals and territories considered remote. Furthermore, Amin et al. [

7], as well as Badiru and Akpabio [

8], established that radio programmes serve as a successful communication channel for instructing rural dwellers about cultivation, sustenance, and animal farming. Radio programmes improve agricultural information sharing in rural communities and expand farming using indigenous languages to engage with farmers and other associated audience groups [

9,

10,

11].

In Oyero’s [

12] words, “combining the potentials of radio stations with the benefits of indigenous language will, to a great extent, bring to realisation the purpose of communicating development messages”. This implies that the role of indigenous languages in agricultural radio programmes is impeccable. Thus, issues relating to pesticides and other relevant information are easily assimilated by farmers, and communicating information on these issues would be made less demanding by utilising indigenous languages in agricultural training and extension administration, which bring new agro-technologies to farmers to expand their yields and profit and upgrade their ways of life. The way forward to achieve this is to encourage using languages that farmers know and can easily relate to. Lowe et al. [

13] note that farmers draw information from diverse sources to enhance their expertise. Therefore, if farmers communicate in their language, it becomes less demanding for both the facilitator and the farmers.

Correct information has been established to be critical to agricultural development when disseminated to stakeholders in a language they understand, thus leading them to embrace innovations wholeheartedly. Therefore, it is necessary to explore radio programmes in indigenous languages from the perspective of programme producers. This is key because farmers who do not know about agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages are likely to be unaware of trends in improved farming practices and, thus, less productive in supporting national and industrial developments. Therefore, programme producers are expected to close this gap by bringing agricultural innovations to the fore that best serve the needs of farmers through the programmes aired. These are producers of U yivin ikyese I kwaghyan (Filling the Food Basket), aired in Tiv; Mukoma gona (Let Us Go Back to Farming), aired in Hausa; and Muryan Manoma (Voice of Farmers), also aired in Hausa. This current study provides a new approach through an assessment of the opinions of producers of such programmes that are aired on radio to gain first-hand feedback on the success or otherwise of such programmes. This will provide an ample opportunity to compare the intent of programme producers to the overall outcome of such programmes. The emphasis here is on agricultural radio programmes aired in indigenous languages, leaving a research gap that the current study thrives on filling.

The following objectives guide the study to identify and analyse the key issues covered by agricultural radio programmes in Indigenous languages, including how these programs address agricultural challenges and the sources of information utilised; evaluate the feedback mechanisms employed by agricultural radio programmes and how producers gauge the influence of these programs on their audience; and assess the challenges faced in delivering agricultural content through radio programmes in Indigenous languages and the strategies used to overcome these challenges.

The study contributes to the actualisation of SDG Goal 2. This was achieved by providing empirical data on how agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages can support agricultural productivity, thereby reducing hunger and making food readily available. This study follows a structure beginning with an introduction that outlines the study’s aim to explore agricultural radio programmes in Hausa and Tiv languages, followed by a methodology section detailing interviews and systematic content analysis of qualitative data. The results section presents key findings related to the programme’s format, topics, audience influence, and feedback mechanisms, culminating in a discussion and conclusion emphasising the importance of indigenous language radio in agricultural development and the need for enhanced partnerships and policy support.

2. Literature Review

Language, media, and national development have significant links. The mass media, for example, educate social groups or players on essential events in society to allow them to engage in everyday choices that shape their lives. Other essential media roles include mobilising the people to participate and holding the government accountable to the people, thereby fostering governance transparency. It is hard to imagine a genuinely national development process in contemporary society without the essential role of communication. However, the media alone cannot fully drive national development efforts. According to Akinfeleye [

14], the mass media contribute to national development and the growth and development of other influences and forces operating simultaneously. The transmission of messages through indigenous languages has been identified as a critical element in promoting the development of the language and culture of people. Language is a way for a group of people to interact and communicate. It also transmits the people’s culture, standards, ideas and beliefs [

15,

16].

Communication is conveyed by language, and the degree of language efficiency can decide the efficacy of communication. Various researchers, such as Ogai and Williams-Umeaba [

17], Adeyeye et al. [

18], and Ndubuisi and Nkamigbo [

19], have concluded that using indigenous languages will increase the efficacy of messages in mass media coverage. Salawu [

20] notes that in knowledge, mobilisation and continuity, media that use indigenous languages are essential, implying the survival of language and culture. In other words, the mass media and services sent to people in their mother tongue are more likely to attract coverage than when the same information is delivered in English or other languages. For example, information or messages on development or behavioural change issues would most likely be helpful. It must first be communicated before any development programmes reach their goal. This is called the creation of awareness or advertising. If you are unquestioning, you can use the media to clarify issues, support the new initiative, or initially develop the common inertia of accepting government policies and programmes.

In Nigeria, people have been suspicious of government policies and development programmes, considering their past knowledge of the non-fulfilment of policy commitments. They also view media campaigns as one of many government propaganda tactics to achieve low-cost exposure or generate more undesirable political impressions. This would be more likely if people heard the message in their native mother tongue that these suspicions would be that. The use of indigenous languages “as the key to people’s hearts” is identified by Olaoye [

21]. The mass media are essential institutions and tools to promote the evolution of the indigenous language because they are a way to unlock the door to wealth.

However, it is disheartening, and regrettably so, too, that the indigenous language has been relegated to the background in Nigerian mass media, and English is the focus of attention. For example, in the case of broadcast media, the Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN) and the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) broadcast English primarily through language services. The national stations broadcast mainly in English except for a few selected substations that run some programmes in their native language in the area in which they operate.

Language is one of the main unifying factors of any person. It is a medium of expression, cultural transmission, identity, and social mobilisation. However, as critical as the mass media is to the development of the country, they have seriously underreported the use of indigenous languages in their programming. Therefore, it is a significant oversight to promote the use of foreign languages (English) to the detriment of hundreds of Nigerian languages. Through their programme, the media can encourage the use of indigenous languages. The Nigerian people’s rich linguistic and cultural heritage can be exploited through programmes like news translation, entertainment, drama and documentaries, news comments, and even commercials. One way to prosper as a country is to encourage and highlight our language and cultural heritage worldwide. The mass media remain essential to this plan.

Radio transmission is fast and reaches a larger dispersed population. As farmers obtain useful radio information, they gradually alter their farming techniques [

22]. Knowledge and understanding are two critical variables in the growth of rural areas. Local awareness also helps farmers. Information dissemination, fresh ideas, and farming methods can provide farmers with new possibilities [

23]. Jenkins and his contemporaries’ research conducted in northern California has shown that mass communication has supplied helpful agricultural information. The experience has been quite significant. Radio has proven to be an essential instrument to improve agricultural production in rural areas. Radio is a reliable and effective medium for disseminating agricultural information and expertise in developing countries [

24].

Radio is a powerful tool that can cover a large area and many people [

25]. The benefit of radio as a means of communication is that its transmission, presentation, and portability are cost-effective. Radio can be an essential tool for teaching farmers if it attracts them to new programmes using modern farming techniques. However, farmers’ literacy is crucial to correctly understanding and executing such programmes [

26]. Rural farmers participate in radio programmes and become more excited and efficient. These programmes effectively deliver messages and information. Pragya and Kashyap [

27] note information on enhanced agriculture, seed improvement, planting, agricultural forestry, improved harvesting methods, soil preservation, marketing, processing, and diversification after harvest. They added that rural radio offers farmers the opportunity to interact through live talk shows, telephone programmes, and regional broadcasts, as well as with each other and other competent authorities such as extension staff and plant and animal experts.

Radio’s power as an extension instrument depends on its capacity to reach many farmers and provide them with information in a language they know about all elements of agricultural manufacturing. This emphasises that radio should be aimed at transforming farmers’ livelihoods by offering helpful information as an instrument for agricultural growth and rural development. Chapman et al. [

28] observed that distant rural farming groups can use radio to enhance agricultural information sharing. A study by the FAO [

29] discovered that radio strengthened unity, improved communicative capacity, provided historical understanding, maintained the environment, and solved community issues. Research suggested the extensive use of radio as an instrument for rural development. Nwagbara and Nwagbara [

25] believe that agricultural programmes have been beneficial. Such programmes have had beneficial effects on small- and large-scale growth. They add that vegetable cultivation, plant safety, pesticides, cereal crops, livestock and poultry, farm management of cereal crops, and agricultural radio and television programmes are viable.

Nwagbara and Nwagbara [

25], drawing inferences from Nepal, further demonstrate that farmers in the Parbat district listened with great interest and enthusiasm for agricultural programmes. To make such programmes regular, more efficient, and exciting, farmers suggested including topics such as vegetable cultivation with the management of hybrid irrigation technology, improved seeds of various plants, source quality, and livestock and poultry breeds. Bhattarai [

30], citing Radio Nepal’s research by the Committee for Economic Development Australia (CEDA) on the effect of agricultural programmes, says that such programmes have helped farmers improve their farming techniques. The farmers received the agricultural programmes of Radio Nepal and Nepal Television for information and understanding. It was discovered that the peasants listened to agricultural programmes with excitement.

Radio education’s first and foremost function is to help farmers embrace new agricultural technology to achieve higher returns and change the age-old low-yield idea. This is exceptionally well done, and it is evident that farmers of different categories have generally adopted new technology. Their willingness to increase their farm income by implementing advanced farming methods is a notable change in their behaviour. Radio serves as an instrument for disseminating credible agriculture-related information to change farming techniques and thus bring about economic transformation in the country [

30].

4. Methodology

The study design employed was explanatory. This type of research involves techniques to investigate why and how a phenomenon happens, to bridge concepts, and to promote better knowledge of causes and effects related to a specific event. The data-collection technique employed was in-depth interviews. The interviews were used to obtain information from producers of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. Giving credence to the effectiveness of the in-depth interview, Sobowale [

40] notes that it enables the researcher to probe deeper into the inner recesses of the interviewee. The interview method is used to explore complex things, gain in-depth insights, and gather diverse participant perspectives [

41]. Thus, the interviewees can express their minds unhindered, unlike the questionnaire, which limits responses to available options and closed spaces. The justification for using an in-depth interview was to gain information from developers, sponsors, and producers of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages.

In-depth interviews were conducted with the producers of agricultural radio programmes and their assistants in the states under study. This included six interviewees from the three states (two per state). They have at least ten years of experience on the job. The interviewees were selected based on their wealth of experience as content creators of such programmes. Specifically, they are producers and their assistants of

U yivin ikyese I kwaghyan (

Filling the Food Basket), aired in Tiv;

Mukoma gona (

Let Us Go Back to Farming), aired in Hausa; and

Muryan Manoma (

Voice of Farmers), also aired in Hausa. They were purposively selected following the principles of qualitative research, which emphasises the importance of collecting different points of view to thoroughly understand the subject matter being studied [

42]. These interviews were conducted with respondents in English and not indigenous languages. This is because they understand and can communicate in English.

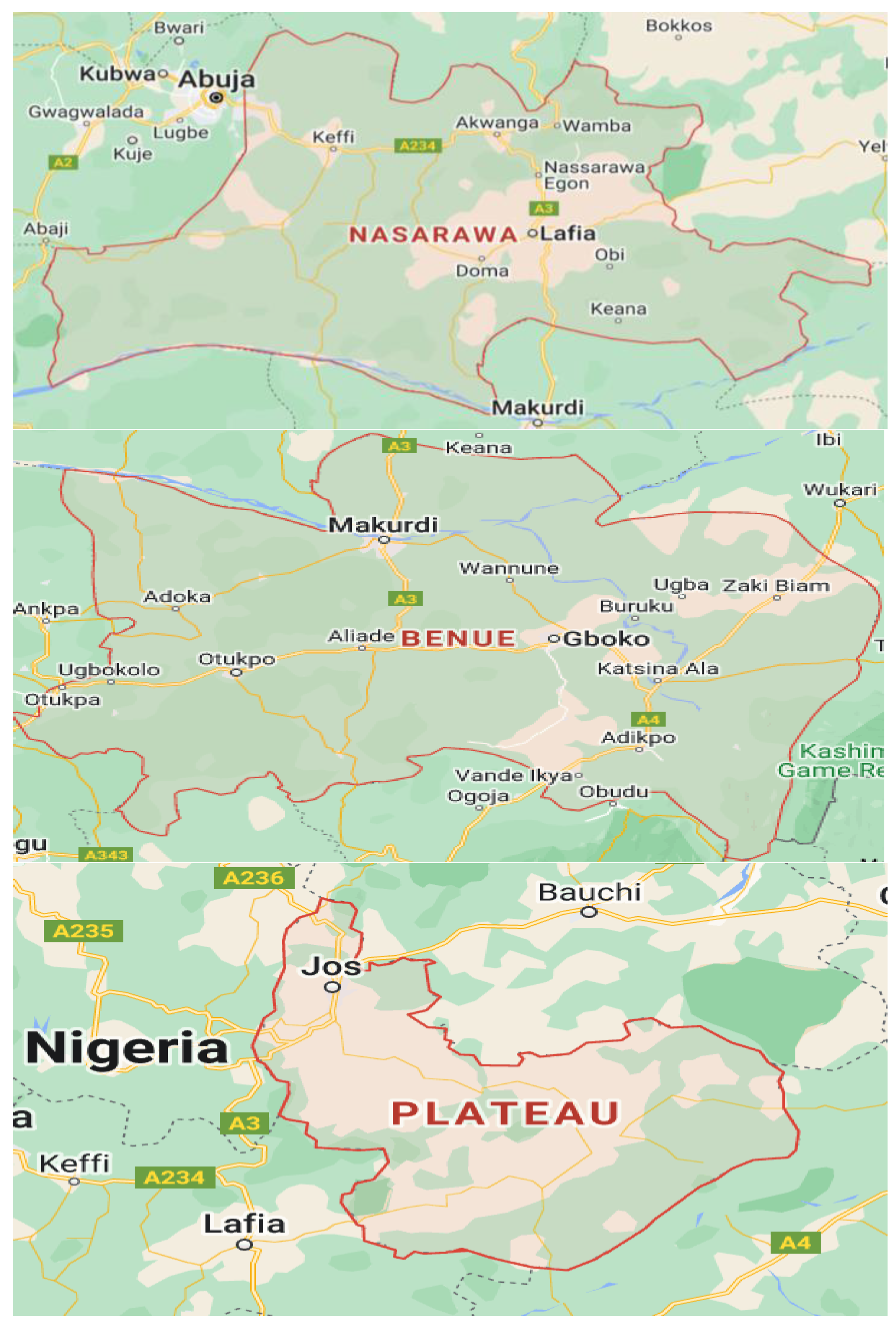

The three top states in the geopolitical region, as seen in

Figure 1, known for successful crop farming (Benue, Nasarawa, and Plateau States), were examined. Furthermore, the states emphasise agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages against other states in the geopolitical zone [

43].

The interview guide was used to obtain helpful information from the appropriate interviewees. A list of questions guided the researchers in the interviews and allowed some follow-up questions to probe the interviewees more deeply. Systematic content analysis (SCA) was used to analyse the interview transcripts [

44]. Systematic content analysis (SCA) is a thorough qualitative research method that examines the text of interviews with a controlled and non-biased approach. The researcher is expected to follow a preordained process to arrange and make meaning out of the content available. This method ensures that the analysis remains constant and logical without prejudice to originality and the interpretation of results. In this study, SCA was adopted to investigate how agricultural programmes in indigenous languages are designed and operated to identify the recurring topics, programme formats, and challenges programme producers face. One of the key attributes of using SCA is its transparency. The method entails step-by-step coding and categorisation processing of data, which allows other researchers to replicate it when necessary. This strengthens the validity of the findings and shows that the interpretation is clear and well-grounded in the methodological process, putting away subjective limitations. SCA enhances the reliability and depth of qualitative analysis, which makes it a valuable tool to aid the understanding of profound experiences such as that of a study of this nature. An interview guide was used to obtain helpful information from appropriate interviewees. A list of questions was used to guide the researcher in the interviews, but some follow-up questions were also allowed to probe the interviewees more deeply. Using the methodology outlined by Mitchell et al. [

45] and Amoo et al. [

46], similar responses were categorised into themes. After reading the transcripts, additional themes were added, resulting in the elaboration, splitting, or combination of topics as needed [

46,

47].

5. Results

The participants were drawn from different radio stations in the selected states. Individually, the producers and assistant producers of the programmes under investigation from Harvest FM Makurdi, Nasarawa Broadcasting Service (NaBS) and Plateau Radio and Television Corporation (PRTVC) were interviewed.

The interviews generated data on the factors influencing the choice of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages by the selected radio stations under investigation.

5.1. Issues Covered in the Programmes

The study showed that various agriculture-related topics are included in the programmes, emphasising farmers who need clarification on improving their yield. According to interviewees, these topics were arrived at based on their interactions with farmers about their interests. All these issues were broadcast in indigenous languages with which farmers could connect. For instance, the programme producer of Muryan Manoma (Voice of Farmers), aired on Plateau Radio and Television Corporation (PRTVC), averred that:

We cover issues of rice, poultry, cassava, maize, and tomato, as well as as many as they are at any point in time, especially in Jos. Different farmers’ groups have their turn discussing issues, speaking about what they do and relating with the public. The public also patronises them and needs information on what goes into the service.

The programme producer of U yivin ikyese I kwaghyan (Filling the Food Basket) further corroborated this assertion. He noted that:

We cover issues related to agriculture and ways that we feel farmers can improve their productivity in terms of the method used and communication in agriculture. We also look at areas where we think we can assist farmers and get closer to them, basically in agriculture for plants and animals.

Agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages in the selected states cover farmers’ issues and provide solutions. Programme producers identify these issues and bring experts to deal with them, thus educating farmers on improving their yield.

In an interview with the producer of Mukoma gona (Let Us Go Back to Farming), it was discovered that the issues covered by the programme were beyond farming. Instead, they turned to the resolution of conflicts between farmers and herders. According to the interviewee, peace is essential for improving agricultural productivity. Therefore, the programmes produced to respond to conflicts between farmers and herders were their little contribution to society.

5.2. Format of the Programme

The study identified the format of the agricultural radio programmes broadcast in indigenous languages in the selected states. It was discovered that the programme format for the three programmes is classified into live and recorded, while the broadcast content is organised into the magazine, interview and call-in.

According to one of the interviewees:

We do primarily call in. We had to deal with people who did not understand broadcasting. As a producer, you must tell them to get inserts in stories or programmes they do not understand. They were more interested in having officials come. However, I insist that they must have experts in different sectors. The conversation is not for those who own the programme but for people who would benefit. If you want to talk about livestock, a member may be into poultry but is not necessarily a vet doctor or livestock expert. It adds value to people who do the business. Some might not be their members, but they can join them when they encounter such information. We use SMS and calls primarily. We have many requests for different niches in agriculture. We have about 30 calls and 15 SMS’ during live programmes. However, you must understand that most Nigerians prefer to talk rather than write, even though you designate a number only for SMS.

Furthermore, two other interviewees corroborated the programme format to conduct interviews and magazines with knowledgeable people in the area to be discussed. They were also asked questions in areas where farmers need clarification.

5.3. Selection of Topics for the Programme

In identifying the criteria for a range of issues for the programmes, this study discovered that producers of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages in the selected states noted that they evaluated the situation per time before coming up with topics to be treated. The topics cover a multiple discussion platform, with programmes related to the entire gamut of agriculture, from seeds, planting and farm maintenance, farm hygiene, and harvesting and processing. On this, one of the producers asserted that:

There are days when we engage people for marketing and about soil. If you are going to be on the farm, you need to know that there is no one restrictive area that we will look at. The topics are many. They vary in the issues we want to discuss. Sometimes, we say, this is what we need to do; sometimes, we talk about support coming from the government. Sometimes, we talk about fertilizers we need to use. We treat such issues if you want to know how to apply farm inputs, such as herbicides. The programmes were basically about knowledge exchange.

Another producer, responding to the criteria for selecting topics for the programmes, noted that they keep in touch with government officials and keep tabs on government policies in selecting issues to keep farmers informed on government interventions in their activities. He noted that:

For example, the Anchor Borrower Scheme dwelt greatly because it was a big window for farmers. For example, this practice in Hausa is called ‘ba da ka ka’, where those who have money would come to buy food crops even before they arrive. On their farms, vulnerable farmers, coming close to October or September when they start harvesting, would sell their produce before harvest is complete because parents are looking for money to send their children to school. Therefore, our awareness often is in that area to discourage them from selling. The motive is for them to wait to sell at a reasonable price. You cannot get a competitive price if you sell off before that season. Even if the price goes up, your client has already paid you.

5.4. Sources of Information for the Programme

The study showed that many sources of information are contacted for the programmes, including experts who are knowledgeable in the field of agriculture from universities around world, the Ministry of Agriculture, the Benue State Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (BENARDA), the Nasarawa Agricultural Development Programme (NADP), the Plateau Agricultural Development Programme (PADP), and other related agencies of government. Laying credence to the above assertion, one of the producers particularly noted that:

We had the Plateau Agricultural Development Programme (PADP). We also had experts from the Poultry Farmers’ Association. Some of them were doctors there. We had experts from rice farmers, business development experts from microfinance banks, and the Plateau State Agricultural Microfinance Bank (the only one in Nigeria currently) under additional financing from FADAMA III. Also, we had a tractorisation programme in which the government gave more than 50% subsidies to farmers in the Plateau state and the tractor ownership scheme. We had to do many sensitisations on that. Some farmers are now owners of tractors. The government arrived with 400 tractors. The first 100 arrived, farmers paid a percentage, and the government paid the rest. That programme helped, and each time we had a programme, there were many calls, and it succeeded in changing the attitude of farmers. Instead of hiring tractors, they could acquire tractors.

Another interviewee asserted that:

We look at issues, the season, and what information people need to know. We look at the experts, and I think whatever you want to do, you must get the appropriate experts to come in and provide the information. I have been working on programmes for a long time now, as well as other business programmes. Still, I am not an expert; therefore, I am bringing in experts who would provide invaluable information that people can use appropriately. We properly analyse the experts we must contact for each programme and then bring them in. If it is government policies, sometimes, officials talk about the implications of these policies.

5.5. Feedback Mechanism for the Programme and Response to Issues Raised by the Audience

The study showed that the feedback mechanism for agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages in the selected states includes short messaging service (SMS) and phone calls. One of the interviewees noted that

We use SMS to get feedback from people, and when we go live, we send our phone numbers to people who call. The number of responses we get is very high because, frequently, from the programme, you see the number of people requesting you to see the calls coming in, continuously calling in, asking questions, and contributing.

The experts responded to the questions raised by the audience, and if the experts were not readily available, the questions were analysed and sent to the experts for a response. One of the interviewees notably indicated that:

The experts addressed pertinent issues. However, if the required experts were not there, we wrote down those salient questions and waited for the concerned officials or experts to come back for the following programme to respond to such questions; you need to speak to people.

5.6. Gauging the Influence of the Programme on the Audience

In assessing the programme’s influence on the audience, it was discovered that the influence was seen on many fronts. These include farmers who own tractors, expand production, resolve conflicts, access government loans, and conduct agro-marketing. The category of persons who brought the resource includes those who are known to be knowledgeable, not people who just came into the system. These stakeholders are also ready to influence farmers’ knowledge.

According to one of the interviewees:

The farmer’s ability to own tractors is one primary parameter. In addition, farmers are expanding from small-scale to the commercial level, which is a big success. That they can also resolve their conflict is also part of success. They need to galvanise; I saw interest from farmers before the last election. Farmers from different local governments started regrouping again to build the new All Farmers Association in Nigeria (AFAN). This was the result of the advocacy the programme had. You can approach the government to do this, such as grading the roads and making them accessible to the agricultural centres and having an advisory team in the southern zone for processing. Individuals have mills, but they are not enough to absorb the produce, so you discover that farmers are losing out on those aspects. If farmers progress, they can get more.

This assertion was further corroborated by another producer, who noted that:

There has been a positive influence so far, so good. There is a response from the public, which means people are listening to the programme. When I started the programme, I was invited to some seminars that were strictly related to the programme, which meant people were looking for the programme. I believe that the programme has a good listenership. The people appreciate the programme even within the station. Some colleagues told me you are trying; please keep it up. The programme has not been failing, so I believe it has had an influence.

5.7. Ensuring Fairness, Balance, and Use of Accuracy in Programmes

The study showed that the programmes provide accuracy, balance and accuracy. To ensure this, one of the interviewees noted:

We try to listen to people, understand them, and present opinions and perspectives, which is one thing we have done, but the airtime is managed. It is limited. So, if someone wants to make a point, it might take two to three minutes, and we do not have that luxury of time. This means that we need to hear that person if someone says something. If problems are raised in the programme and are not sorted out, we take them to the next programme and ask experts according to the following schedule. No one stops someone from asking questions. Some people repeat what others say, but we must listen to them. Although the airtime was not too good, the participation was excellent. People from Bauchi, Southern Kaduna and other surrounding areas participated.

This assertion was further corroborated by another interviewee who noted that:

I usually look at the season, trends, and research. You do not bring a topic up without researching the topic.

5.8. Handling Primarily Science-Agriculture Issues

In handling primarily scientific agriculture issues, it was discovered that professionals such as extension workers and veterinarians are contacted to shed more light on educating farmers and help them make informed decisions. One of the interviewees particularly noted that:

This is where the role of experts comes into play. No layperson will tell you he will do this or that because he is doing this programme. It would be best to involve an expert in your story; otherwise, you misinform the public about your actions. We get experts who come to give us professional information. For example, only an expert would tell you about seeds when talking about seeds. Moreover, that is where Nigerians are getting it wrong. We have produced some programmes on seeds so people can get to know them before the new growing season. However, if you do not get seeds, people take grains and plants as seeds. These are not seeds. You plant grains for consumption and not seeds prepared for planting. So, the experts we bring in can differentiate, and the people who listen well get value for it.

5.9. Challenges Faced in Covering Agricultural Issues and How They Are Overcome

It was discovered that the challenges of covering agricultural problems are enormous. These challenges include obsolete equipment, nonavailability of resource persons, scarcity of professionals willing to make themselves available for the programme, and bad road networks to assess some farmlands belonging to farmers. One of the interviewees noted that:

The challenges are enormous and numerous, but we thank God for everything. Most of the time, you invite those resource persons, and they keep posting to you. They tell you to come tomorrow or today, and you may hope that person will discuss a topic. That implies that you have to start looking for another guest to come and discuss during that programme. Another issue is a power outage. We do not have the power to produce programmes. Another challenge is to ensure that farmers are supported in understanding what is being aired.

In trying to overcome the challenges identified, one of the interviewees noted that:

We usually talk about the power issue because I have my system, so when I charge the computer, I install the software inside to use that system to edit my programme even when there is no power. If the system is fully charged, I write my programme to solve the problem somehow in that area. We have been proactive in attracting guests for the programme we plan. If one fails, we look for two to three guests to use the other person. In the language area, we try as much as possible to tell our guests how we want to use the language so these people will understand, and when editing, we try to remove things we do not like from the programme.

6. Discussion

The study showed that the factors that influence the choice of agricultural radio programmes aired in indigenous languages by the chosen radio station are the format of the programme, the burning topics per season, the availability of the discussants, the feedback mechanism of previous programmes, and the influence of the programme on the audience, among others. This deals with various issues related to agriculture, which are covered in the programmes, with particular emphasis on farmers needing clarification on improving their yield. These issues were broadcast in indigenous languages that farmers could connect with, such as rice, poultry, cassava, maize, and tomato. The different farmer groups have their turn discussing topics, speaking about what they do, and relating with the public because the audience also patronises them and, therefore, needs information on what goes into the service. The programmes covered various issues related to agriculture and how farmers can improve their productivity regarding their methods and communication in agriculture. This was carried out by providing the necessary information to improve productivity. Stefano, Hendriks, Stilwell, and Morris [

48] support this finding. Wang et al. [

49] and Khan et al. [

50] all averred the importance of disseminating correct information to farmers through the right channel to improve agricultural productivity.

Agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages in the selected states cover issues affecting farmers and provide solutions to the matters raised or identified before, during, and after the programmes aired. Programme producers identify these issues and bring in experts who deal with them, thus educating farmers on improving their yield. The study discovered that in some situations, the topics covered by the programme were beyond agriculture but went so far as to investigate conflict resolution to ensure peaceful coexistence between farmers and other stakeholders in that sector. The study identified the format of the agricultural radio programmes aired in indigenous languages in the selected states. It was discovered that the programme format for the three programmes is classified into magazine, interview, call-in, and pre-recorded programmes. This corroborates the findings of Ferris et al. [

51], who demonstrated that incorporating farmer perspectives and their voices is particularly crucial.

This study discovered that producers of agricultural radio programmes in Indigenous languages in the selected states choose topics that evaluate the situation per time before addressing the issues to be treated. Topics cover a multiple discussion platform, with programmes related to the entire gamut of agriculture, from seeds, planting and farm maintenance, farm hygiene, and harvesting and processing. The study showed that many information sources are contacted for the programmes, including experts who are knowledgeable in the field of agriculture from universities around the Ministry of Agriculture, Benue State Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (BENARDA), Nasarawa Agricultural Development Programme (NADP), Plateau Agricultural Development Programme (PADP), and other related agencies of the government. This finding substantiates that of Hailu et al. [

24], who suggested that radio stations invest in the participation of farmers in programmes if they are to be efficient and maintain listening as designed to ensure that they frequently invite experienced farmers and researchers to their talk shows. It is worth noting that when they come up with their schedule, radio programmers should also work carefully with their audience because this will assist them in attracting a larger audience.

If well made, agricultural radio programmes aired in indigenous languages will attract a large audience; this will also rely on content, format or style, and presentation, implying that radio producers and agricultural programmers should function concurrently. Toepista [

52] believes that extension services must be integrated with radio farming programmes to serve rural farming communities efficiently. Partnerships are essential for farming organisations and radio stations to overcome the difficulties experienced by both parties. Toepista [

52] also stated that radio stations and producers must discover sustainable methods to package innovative programmes; partnerships with agricultural organisations in producing programmes, compared to donor-funded programmes, would be more durable and increase growth. This emphasises the need for feedback, as identified in this study. Therefore, the feedback mechanism for agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages in the selected states includes SMS and phone calls. Experts respond to issues the audience raises; if experts are not readily available, the questions are noted and transmitted to the experts for a response. To gauge the programme’s influence on the audience, it was discovered that the influence was seen on many fronts. These include farmers who own tractors, expand production, resolve conflicts, and have access to government loans and agro-marketing. The resources brought in are provided by knowledgeable individuals, not people who are just coming into the system; these are stakeholders who are also ready to impart knowledge to farmers.

Radio remains a primary media platform in most households [

53]. The study showed that the programmes ensure fairness, balance, and precision. In providing this, the study found that producers try to listen to farmers, understand them, and communicate opinions and perspectives. The season is examined to deliver this, and trending activities are discussed to ensure all sectors are carried out. In handling primarily scientific agriculture issues, it was discovered that professionals such as extension workers and veterinarians are contacted to shed more light on issues to educate farmers and help them make informed decisions. However, it was discovered that the challenges in covering agricultural problems are enormous. These challenges include obsolete equipment, nonavailability of resource persons, scarcity of professionals who will make themselves available for the programme, and bad road networks to assess some farmlands belonging to farmers.

Findings from this study emphasise that agenda setting and development media theories significantly influence how radio programmes in Indigenous languages shape agricultural development in North-Central Nigeria. By prioritising agricultural topics, these programmes highlight critical issues such as farming techniques, market access, and sustainable practices, thereby framing the agricultural discourse within the community [

32]. This focus raises awareness and empowers local farmers by providing relevant information in their native languages, enhancing comprehension and engagement [

54]. Consequently, these programs catalyse agricultural innovation and community participation, facilitating the dissemination of best practices and local success stories [

55]. As a result, the intersection of media and agriculture becomes a dynamic space for development, reinforcing the importance of culturally relevant communication in driving sustainable agricultural progress [

56].

7. Conclusions

Following the findings of this study, the following conclusions have been reached.

Agriculture-related issues are covered in indigenous languages in agricultural radio programmes, highlighting that farmers need clarification on how to improve their yields. The specific issues covered are those related to rice, poultry, cassava, maize, and tomatoes, as well as how farmers can improve their productivity concerning the method used and communication in agriculture. The programme format for the agricultural radio programmes broadcast in indigenous languages in the selected states is classified into magazine, interview, call-in, and recorded programmes. The topics discussed in the programmes cover a multiple discussion platform, with programmes related to the entire gamut of agriculture, from seeds, planting, farm maintenance, farm hygiene, and harvesting and processing. Information sources contacted for the programmes are experts knowledgeable in the field of agriculture from universities, the Ministry of Agriculture, Benue State Agricultural and Rural Development Authority (BENARDA), Nasarawa Agricultural Development Programme (NADP), Plateau Agricultural Development Programme (PADP) and other related agencies of government. The feedback mechanism for agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages in the selected states includes SMS and phone calls. The challenges in addressing agricultural issues are enormous. These challenges include obsolete equipment, non-availability of resource persons, scarcity of professionals willing to make themselves available for the programme, and bad road networks to assess some farmlands belonging to farmers.

8. Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the following recommendations are made.

Agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages should continue to be encouraged to improve farmers’ productivity. These programmes succinctly improve the knowledge gap in farming by providing the audience with practical tips in agriculture for improved productivity. These tips include new farming techniques, details in weather forecasts, competing market prices for farm products, and updates on government policies relating to agriculture.

With the available information sources for the programmes, as discovered by the study, efforts should be made to invite farmers to the programmes to hear from them and encourage their colleagues. This integration allows farmers to share their life experiences, challenges and success stories and promotes a sense of community and learning from peers. It creates a sense of togetherness as farmers watch their co-workers participate in the project and encourage others to engage with the content to drive positive change. Thus, the overall effectiveness of the programmes will be improved.

Various media establishments should revisit issues related to obsolete equipment. To solve this problem, media organisations should invest in modernising their tools to ensure that their programmes stay relevant. Such programmes must be conveyed clearly and professionally to reach a wider audience and increase the reliability of the information provided.

Efforts must also be made to provide funds for the owners’ media establishments to cover agriculture adequately. The media can expand agricultural coverage with appropriate funding to improve project sustainability. Cooperation with agricultural organisations, government support, and private investment can ensure that farmers receive regular, comprehensive updates, which helps increase agricultural production.