Abstract

Institutions have long shaped human life. One of their key roles is to balance the interests of the community with those of smaller sub-groups and individuals. The larger and more complex human communities are, the more pressing the need for functioning institutions. Climate change is an unprecedented threat to the balance between the interests of the community and those of sub-groups and individuals. Yet, formal institutions have failed to address the climate crisis, and while there have been numerous efforts to negotiate global climate solutions, effective enforcement mechanisms are lacking. In contrast, economic institutions have expanded their global reach, especially after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This paper argues that the absence of effective institutions to mitigate climate change warrants a closer look at standard market economics since economic transactions have an outsized impact on climate change. Moreover, standard market economics has not only succeeded in implementing formal economic agreements but also propagated its informal institutional mindsets. Four underlying principles of the market economic mindset, namely its understanding of time, place, context, and growth, are analyzed to illustrate how standard market economics impacts the global climate crisis. The analysis shows that by making these underlying principles transparent, pathways for local and regional climate solutions can be advanced even in the absence of effective formal institutions that enforce climate mitigation at the global level.

1. Introduction

We live in the age of market economics. This implies that the institution economy is the most influential institution of our age. Environmental problems like global climate change are routinely framed as the consequence of economic activity. Reducing them will therefore have economic consequences. Yet, not reducing them has consequences as well. In fact, environmental degradation, in general, and climate change, in particular, are becoming ever more costly for both society and the economy in addition to the environmental losses they generate [1,2,3,4,5]. The costs of climate change are associated with what economists describe as market failures. Chief among them are externality and public good failures. Externalities are the unaccounted-for side effects of economic activity [6,7,8]. A coal-fired power plant, for example, intends to produce energy to meet heating, cooling, and transportation needs. Yet, in meeting these needs, it emits CO2 and other greenhouse gases like methane and other carbon oxides (COx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfor oxides (SOx) and more. The costs of these emissions are not allocated to the energy producers who generate them. Instead, they are borne by everyone who depends on the atmosphere and suffers from the effects of the emissions. Those shouldering the cost burdens include farmers who struggle with more frequent droughts; beverage companies who face growing water shortages; fisheries whose fish stocks collapse due to rising water temperatures; homeowners and businesses who lose their homes and livelihoods to wildfires, flooding events, and hurricanes; insurance companies processing the claims of more frequent natural disasters; and the list goes on.

Public goods are defined by economists as non-exclusion and non-rival. Non-exclusion means that no one can be excluded from the use of a public good regardless of whether they are willing to pay for its use or protect it. Non-rival means that one person’s use does not impact its use by others. This second condition has turned out to be incorrect for most public goods. The public good ‘atmosphere’, for example, is non-exclusive since no one can be excluded from its use; yet the non-rival criterion does not hold since the use of the atmosphere as a giant receptacle for gaseous emissions degrades its quality and impacts other users. This is what Garret Hardin called ‘the tragedy of the commons’ [9], also referred to as public good failure [10,11].

The costs of market failures are borne by society at large and not by those who cause them, unless policy interventions shift the cost burden back to those who cause them. Market failures, therefore, underestimate the costs and overestimate the benefits of the economic activity that causes them. For example, the negative externalities caused by the production and use of energy are not included in the price of energy, making energy seemingly less costly and more valuable than it is. As a result, more energy is used than what would be optimal for society as a whole. [12,13].

Policy measures are supposed to correct the value distortions of market failures. It is, therefore, generally accepted that the best outcome for society, which welfare theory calls the socially optimal state, requires effective policies [13]. To be effective, policies must come with a set of procedures to implement and enforce them. They must, therefore, take customs, social and cultural norms, and governance structures into account to determine both ‘what’ should be done and ‘how’ it should be done. Policies, therefore, reflect the formal and informal institutional arrangements, through which a society arrives at its collective decisions and achieves its collective goals. Formal institutions include parliaments, legal systems, banks, schools, religious organizations, and other formal arrangements. Informal institutions are the less-tangible customs, social norms, mindsets, and rules that ensure that collective decisions are respected.

Climate change is complex and rife with market failures and competing social and individual interests [14]. Effective climate solutions must be able to deal with this complexity both in terms of ‘what’ needs to be done and ‘how’ it can be done. Yet, while it is a global problem, there are no formal institutions at the global level to adjudicate the competing interests of those who benefit from climate change and those who suffer its consequences. Local and regional environmental problems can be addressed by local or national regulations and laws. Climate change requires global action.

This article suggests that climate change solutions can be advanced by shifting attention from formal to informal institutions. Given the global reach of the economy, it is especially important to uncover and communicate the informal mindsets of market economics. To illustrate the power of uncovering hidden mindsets, four key assumptions of standard market economics are discussed, namely its understanding of time, place, context, and growth. In making these assumptions of the economic mindset transparent, new pathways can be unlocked for more effective climate policies even in the absence of formal global institutions. It is further argued that a shift in the market economic mindset is already under way as evidenced by the local climate initiatives that are emerging even in the absence of effective global agreements.

2. Methodology

This article follows the analytical premise of mindset theory, which originated in the field of psychology [15]. Mindset theory explains how beliefs about abilities, skills, and behaviors impact motivation, learning, and ultimately outcomes. More broadly, it explores how theory shapes mindsets to the point where mindsets are ultimately implicit theories that shape broader beliefs, habits, and abilities [16].

The article applies the concept of mindset theory to the field of institutional economics and explores how standard economic theory and its assumptions about consumer and producer behavior and their interaction in (abstract and concrete) markets shape today’s mindsets. It argues that the theory that forms today’s dominant economic mindset, namely standard market economics, is not merely a description of economic behavior and actions. Instead, it has shaped behaviors and actions beyond the realm of the institution economy. Economic theory has thus shaped human belief systems and behaviors with significant implications for how we humans interact with each other and with our environment.

This article uses the example of global climate change to illustrate the implications of mindset theory. It unpacks four underlying principles of the standard market economic mindset to show how its logic has become a dominant institutional mindset globally. Yet, unpacking the assumptions that market economics makes about time, place, context, and growth illustrates not only the dominance of the market economic mindset but also emerging efforts to reclaim more diverse solutions to climate change that start at the local and regional level.

3. Defining Institutions

According to Durkheim, institutions and their genesis and workings are the primary focus of the social sciences, including sociology, anthropology, political science, and economics [17,18]. Institutions are defined as established organizations, practices, and recognized relationships in society and culture. Institutions are characterized by “stable, valued, recurring patterns of behavior” [19], yet they are also more than behavioral patterns. Instead, they form “integrated systems of rules and procedures that structure social interactions” [20].

One of the key aims of institutions is to balance and coordinate the potentially competing interests of individuals, sub-groups, and society as a whole. North suggests that institutions ultimately work to provide structure to societies and incentivize those who adhere to established structures and procedures while penalizing those who do not [21,22]. Institutions are therefore a reflection of collective actions and not simply a collective of individuals. For example, when sociologists speak about the family, it implies groups of people organized in a particular way and holding certain functions and roles: they raise children, hold established gender roles, and assume various actions expected of a group called ‘family’.

This example also highlights the somewhat fluid distinction between formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include governments, school systems, financial institutions, and similar formalized entities. Informal institutions tend to be less tangible and transmit more unspoken but no less influential norms and behaviors, which can be understood as the mindset of an institution. Comparative studies of formal and informal institutions have, for example, pointed to differences and commonalities in cultural norms related to communal versus individual rights and obligations. [23,24]. Classifications of social institutions vary, yet there is broad agreement that there are at least five: family, religion, education, government, and the economy [25,26,27].

- Family is the earliest institution we experience. The family is the center of a child’s early life. It shapes cultural norms, values, attitudes, and behaviors, including a sense of belonging. Norms about what constitutes a family and what roles are expected of its members differ across cultures. They also evolve, and different family types are becoming increasingly acceptable, while rigid family structures and gender norm are declining. At the same time, family units have become smaller, and individual pursuits have taken greater precedence over family obligations. This is reminiscent of the individual decision maker in economic theory who seeks to maximize their own self-interest. One of the downsides of this development may be a growing sense of isolation and loneliness that has been observed across different cultures [28,29]. Beyond human isolation, the preference for individualism may also come with a growing sense of isolation from nature [30,31].

- Religion too has formal and informal aspects that have evolved. Its formal and informal expressions are also associated with ethnicity and culture. Religion once dominated most societies, including those that are considered secular today. Most formal religious teachings include a sense of social obligation and responsibility to the poor. Yet, not all extend this sense of obligation to nature. Much has been written about the negative impact of Christianity, for example, on nature, which is to be subdued and used for human purposes [32]. Others have argued that this is a misunderstanding of the Christian ethic, which recognizes that humans are a part of creation [33,34].

- Education is an institution with far-reaching impact, especially since the introduction of mandatory schooling. The rise of the Enlightenment in 17th century Europe and its emphasis on education and knowledge acquisition made education increasingly powerful. Its formal arrangements include schools, research institutions, and curricula. Its aims include imparting skills and knowledge to serve the economy and governance, and also specific societal goals. In the United States, for example, education became an important facilitator to form the American melting pot out of the many immigrant cultures represented in the American citizenry. More recently, educational intuitions have experienced skepticism and even hostility toward science and factual knowledge compared to personal opinion and perception [35,36]. This includes the persistent denial of climate change despite overwhelming scientific evidence to the contrary [37,38].

- Government is the institution at the forefront of balancing the interests of society, its sub-groups, and individuals. Its formal institutions include the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government and their documents, rules, and operations. As individuals are socialized in their family, religious group, and school, they will learn to obey the laws, regulations, and norms of the institution government. This includes less tangible informal institutional mindsets like trust, customs, and habits which all play an important role in ensuring that the institution government functions. Recent findings suggest that trust is eroding, including in some of the world’s strongest economies like those of Japan, Korea, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States [39,40]. The World Values Survey found a global decline in institutional trust, with almost one-quarter of respondents expressing little to no trust in their governments and legislative institutions [41]. This does not bode well for policies.

- Economy-related institutions organize the three big spheres of economics, namely what to produce, how to produce it, and for whom to produce. In a market economy, these three spheres are organized through decentralized markets where individual actors communicate their interests in producing goods and services (what), allocating the necessary resources to do so (how), and in purchasing them to meet their needs and wants (for whom). The institution ‘economy’ relies heavily on the institution ‘government’ to enforce property rights, for example, including the right to one’s own labor. Without private property protections, a market economy cannot function. Yet the extend to which economic institutions are protected, and how they balance the interests of society as a whole with those of sub-groups and individuals, reflects informal institutional mindsets and cultural norms. While some would argue that markets and their expression of individual preferences must be protected at all costs, others would argue that individuals and social norms must be protected from the market economy. Some of these informal but no less influential characteristics of the market economy will be discussed in the following section of this article.

As this brief review of five key institutions illustrates, formal institutions and their informal mindsets influence individuals and society as a whole. While institutions tend to be stable and slow to change, they are not static. The dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of central planning economies (with the exception of Cuba and North Korea) is a relatively recent example of extensive institutional change. It gave rise to market economies around the world, even as different political systems, education systems, and religious institutions persist. History is rife with examples of institutional change from the end of feudalism and the abolishment of slavery to the rise of the Enlightenment.

It is generally accepted that formal institutions also come with a shift in informal institutional mindsets. Some take a co-evolutionary view and argue that formal institutions shape informal institutional mindsets and vice versa [42,43]. Acemoglu and Robinson, for example, argue that economic prosperity depends to a large extend on governance and specifically on inclusive decision making [44,45]. Institutions are inclusive when there is broad participation in the decision process. Broad participation, in turn, facilitates innovation since it motivates individuals to use their talents and ideas. This in turn gives rise to prosperity. In other words, it is the congruence between a creative mindset (innovation) and formal decision-making arrangements (inclusiveness) that brings about prosperity. Informal mindsets can also hinder formal institutions. A (formal) governance structure of democracy, for example, that prevents its citizens from expressing their (informal) ideas will not encourage creativity or prosperity despite the fact that its democracy is presumably participatory. As the sociologist Max Weber argued, the protestant work ethic of industriousness and striving gave rise to capitalism, and capitalism rewards a mindset of individual striving and industriousness [46]. The global expansion of standard market economics (formal) can therefore shape social and cultural norms (informal) and influence not only the institution ‘economy’, but other institutions as well.

This illustrates the premise of mindset theory that argues that theory shapes mindsets. The implications for a complex global issue like climate change are significant. Given its global reach, one might assume that a global economic mindset is useful in addressing a global issue like climate change. Yet, if the mindset of market economics prioritizes individual pursuits over obligations to the global commons, its global expansion will not protect the global commons but undermine it instead.

4. Unpacking the Institution ‘Economy’

Today’s institution ‘economy’ is synonymous with market economics since alternative economic models like central planning and traditional economies have all but disappeared. This begs the question whether losing the diversity of economic models that guide the ways in which we organize our economies might have similar consequences as the loss of bio-diversity [47]. Socio-diversity can be described as the diverse arrangements by which people have organized their (formal) institution ‘economy’ and the (informal) assumptions, values, and behaviors that shape it. This does not suggest that central-planning economies were better than market economies in preventing climate change or mitigating its effects. It suggests instead that examining the theoretical tenets and assumptions of standard market economics may yield valuable insights about the mindset of market economics and its implications for climate policies. Four key concepts of standard market economics are particularly relevant: its understanding of (1) time, (2) place, (3) context, and (4) growth.

4.1. Time

Time is a key concept in economics, as demonstrated by the common expression ‘time is money’. It implies that faster is better. An increase in productivity means that more will be produced within the same time period. In addition to speed, standard market economics values the present over the future. Decisions about production (what), resource use (how), and consumption (for whom) discount the future. This makes conserving resources irrational and immediate gratification rational. Only if interest rates were zero would it make sense to conserve resources rather than using or investing them in the present. Yet, a plant that may be considered a weed today and found to have medicinal qualities tomorrow suggests the opposite. It would make its use today less valuable.

Economists themselves recognize the pitfalls of discounting the future and its negative consequences for future generations [48,49,50,51]. A solution proposed by the economist Gabriela Chichilnisky, who designed the carbon markets outlined in the Kyoto protocols [52], suggests a non-dictatorship criterion to balance short-sighted interests (present) and idealism (future) [53,54]. Chichilnisky argues that as both present and future uses are weighed, they must both be represented by non-dictatorships rather than by individuals who are more likely to represent individual interests rather than societal ones.

Discounting also raises fundamental questions about how time is viewed. Biological and ecological time do not have the same priority for speed as economic time. Species and minerals evolve over long time periods. The sequential time of economics can best be described by the Greek word Chronos or chronological time. The Greek word Chairos describes time that is fulfilled and focuses on relationships and meaning. Chairos and Chronos time reflect distinct cultural norms that are not easily compatible [55,56]. The Osage scholar Tink Tinker writes:

“History in the sense that the West has understood it… has not existed for Indian people and is imposed on us. Of course, Indian people understand the past; we tell stories of the past and pass on traditions that way.... Where time is a factor it’s always cyclical time. Even one’s lifetime is considered a cycle of existence. The universe goes on when someone dies, and when a new baby is born the cycle begins over again. So that I like to insist, for instance, that notions of temporal progression in modern economics have to be replaced with a dynamic stasis in order to satisfy American Indian cultural values. The important thing is not progress or advancement but maintaining harmony and balance in the universe around us.”[57]

Modern market economics demands a universal understanding of sequential time shaped by speed, instant gratification, and global markets that are open for business 24 h a day, 365 days a year. This runs counter to the long-term cyclical nature of climate change, which becomes visible only over the long run and through sometimes erratic fluctuations.

4.2. Place

Modern market economics has little concern for place. In fact, it prides itself on the fact that place is largely irrelevant. The same technologies, processes, and designs are replicated anywhere, irrespective of the specifics of a place. Production, for example, is primarily concerned with costs but has little concerns for where its resources come from or where its emission and waste go. As long as costs are low, it is justified to move resources, consumer goods, and waste from one location to another, while place has no intrinsic value. One of the expressions of the detachment from place is that financial centers, shopping malls, and production sites look increasingly alike anywhere in the world. The virtual economy takes the notion of placelessness to a new level as it operates in a virtual global space [58].

In contrast, organisms are shaped by their place and impact it in return. In the words of the biologist E.O. Wilson, place leaves its mark [59]. Variations of the same species, for example, can develop into distinctly different species when they are separated by spatial barriers. We humans too are shaped by place. Some feel drawn to the mountains, while others need the ocean close by to feel at home; some love heat, while others like snow. Psychologists suggest that we carry the pictures of our place within us. When the impact of place is neglected, the result is a loss of identity and belonging [60,61]. It seems doubtful that the global market can replace the identities associated with diverse places.

The Nobel laureate George Akerlof acknowledges the importance of identity in economic decision making and welfare creation [62,63]. The loss of identity can even lead to violence just like overly rigid identities of in-groups and out-groups can have the same results [64,65,66,67]. Place-specific knowledge is also critical to sustainable development decisions that seek to balance economic and environmental objectives. Local precipitation patterns, topography, soil conditions, and a host of other local characteristics are critical to assessing what practices contribute to sustainable outcomes. Decisions that are based on generic information and do not take specific conditions into account can lead to unintended consequences and undermine rather than advance sustainability goals. While climate change draws attention to the global commons, it requires local action and place-specific knowledge, especially regarding local and regional ecosystems that can impact global tipping points. The deforestation of the Amazon, for example, is crucial for global carbon sequestration and climate regulation; its protection and sustainable management requires different knowledge than the protection of another critical forest system, namely the Boreal forests. Coral reefs are vital for marine biodiversity and the sequestration of carbon; preventing their collapse requires significant expertise about coastal ecosystems, yet this expertise is different than the one needed to protect Mangroves, which also support marine biodiversity and protect coastal areas. These examples illustrate the importance of place-specific knowledge despite its neglect in standard economics.

4.3. Context

Ecosystems cannot be understood without context. Mutation, cross-fertilization, adaptation, parasitism, and symbiosis all illustrate the fact that ecosystems and the organisms that comprise them are shaped by each other. More plant and animal species go extinct due to the loss of their habitat than due to any threat to the species itself. The various experiments we humans devised to combat a pest by introducing a predator illustrate the importance of context knowledge. An example is the cane toad that was brough to Australia from Hawaii to combat the sugar cane beetle, which was destroying Australian sugar cane crops. 100 toads were brought to Australia to breed and approximately 2000 were released in the wild. Since they had no natural predators, they multiplied to an estimated 200 million, and since the toads were not interested in their intended prey, they decimated other native species.

On the surface, modern market economics understands the value of context systems. After all, the economy receives natural resources (environmental context) and labor (social context) to produce useful products. Yet, the value of the natural resources and the labor inputs is solely determined on the basis of their contribution to economic production. What is not considered is how the workers themselves or the communities they come from are impacted by their work experience. Nor is the impact of extracting natural resources on the environment itself considered, and when oil is extracted to produce energy, the destruction of the land surrounding the drilling site does not impact the value of the oil. In other words, the context that sustains the labor pool and the environmental resources in the first place remains invisible.

This contextless understanding of the economy has led to the overuse of numerous unaccounted-for contributions especially of women, the poor, nature itself, and all those who cannot assert their value in the marketplace [68,69]. Efforts to estimate the unaccounted-for value of those who sustain the labor force and the environment remain incomplete. Even laudatory efforts like calculating the Maximum Sustainable Yield of fisheries and forest ecosystems, for example, have vastly overestimated how much wood can be harvested and how much fish can be caught. These efforts test our capacity to assess the value of complex ecosystems [70,71].

The dependence of individual organisms on their context systems also raises questions about the notion of the self-reliant individual decision maker of modern market economics. A study conducted by the economist Robert Frank illustrates how the logic of market economics itself has shaped mindsets and behaviors. Frank found that those trained in economic theory were more likely to behave in self-interested and opportunistic ways than those who had no background in economics; and those trained in ecnomics also expected others to be more selfish and opportunistic [72].

Some indigenous societies challenge the idea that humans can achieve well-being devoid of social and environmental contexts. Acting in the interest of the whole community is in fact acting in one’s own self-interest. Economists like Gowdy, Sahlins, Diwan, and others [73,74,75] describe cultures where affluence is defined as “...a state in which a person is surrounded by other persons for whom s/he cares and who care for this person”, where “selfishness is considered an immoral act” and where the needs of an individual are viewed as inseparably linked to those of the community [76]. This is quite different from the mindset of market economics and its ideal of the individual interest-maximizing economic actor who makes decisions in splendid isolation. The recent COVID pandemic further illustrates the fallacy of this contextless view, as the detrimental effects of social isolation were a reminder of the need for social context and connections [77,78,79].

4.4. Growth

The institution ‘economy’ is inextricably linked to growth. Economic theory describes consumers as self-interested individuals intent on maximizing their own satisfaction. They gain satisfaction chiefly by meeting their consumption needs and wants. Economists call this the non-satiation principle. It implies that more is always better and there is therefore a constant drive to increase consumption. The producers of standard economic theory are also characterized by limitless desires. They seek to maximize profits, defined as revenues minus costs, which implies two logical success strategies, namely cutting costs and growing revenue. In a profit-maximizing world, the billion-dollar bonuses of fortune 500 companies are rational as long as their executives succeed in further maximizing company profits.

The theoretical underpinning of growth as the engine of the standard economic model has quite practical consequences. The health of an economy is measured in the growth of its GDP, that is the total amount of goods and services produced measured in monetary units (i.e., dollars). The underlying assumption is that GDP does not only measure economic output but well-being. Growth implies increased income, more consumption, and thus a higher quality of life. When the economy shrinks, the assumption, therefore, is that well-being also declines despite evidence to the contrary [80,81].

A related justification of economic growth is that growth is the best way to address disparities. The argument suggests that it is difficult to address inequality by taking away from the haves to give to the have-nots. It is easier to give the additional economic output to the have-nots without taking away from the haves, and the result will be shrinking inequality. There may be some evidence that this strategy has worked even though inequality has grown since the 1970s. Studies suggest that income and life expectancy have risen globally, and by 2020, more than 50% of the world’s population were considered a part of the middle class [82]. There is, however, little evidence to suggest that a growing middle class will also be more content [83].

One of the drivers of the growth paradigm is the reliance on monetary measures as the most broadly accepted indicator of economic performance. An example is the so-called Hartwick rule or weak sustainability principle. It suggests that non-renewable resources can be managed sustainably as long as the earnings they generate outweigh the consumption of natural capital [84,85]. This assumes that human-produced capital can be a substitute for natural capital without repercussions. There is little evidence that this rule holds as human-made capital innovations have not been able to replicate the efficiency or complexity of natural systems [86].

As this review of four key assumptions of economic theory illustrates, it will be challenging to align the institution economy with the needs of global climate change mitigation. Yet, some solutions may already be emerging.

5. Formal and Informal Institutions and Climate Change

Efforts to mitigate climate change often have unintended consequences. Driving an electric car, for example, using public transportation, and eating more locally produced food are behaviors that reduce CO2 emissions and should be incentivized. Yet, the benefits of these behaviors are limited if only a few accept the incentives. This is known as the free-riding problem, where some rely on the responsible behavior of others to achieve the best outcome for the global commons. Moreover, if the incentives for electric vehicles reduce public transportation ridership, they may prove counterproductive; if lower-income households cannot afford to use public transportation because it is too expensive, CO2 emissions may actually increase since low-income households tend to be the less likely to afford electric or hybrid vehicles; and even though locally produced food can have both health and carbon benefits, its costs may be prohibitive so that consumers will continue to buy subsidized lower-priced food items despite the higher CO2 emissions associated with their longer transportation routes. These examples illustrate that a complex problem like climate change tests the limits of standard policies.

5.1. Formal Institutions and Climate Change

One of the first efforts to balance economic and environmental goals was the so-called Brundtland report named after the former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland [87]. The report, entitled ‘Our Common Future’, called for a global agreement to reduce CO2 emissions, protect biodiversity, and address other environmental threats. Regional collaborations across national boundaries served as successful examples. Improving the water quality of the Great Lakes in the United States and the Rhine river in Western Europe, for example, required local, regional, and national governments to collaborate to reduce water pollution and achieve higher water quality standards [88,89,90,91,92]. Yet, formal institutions at the global level have few levers to get those who benefit from greenhouse gas emissions to collaborate. Those who reaped the greatest benefits of CO2 emissions cannot be forced to collaborate, while those most vulnerable to its effects (like island nations, for example) may lack the political and economic power to assert their needs.

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 was another attempt at formal institutional action. One of its objectives was to reduce CO2 emissions to 1980s levels. The negotiations proved challenging. The U.S. sought to shift the focus from the outsize impact of affluent lifestyles to the impact of population growth. The biologist Paul Ehrlich proposed the IPAT equation, whereby the environmental impact (I) is determined by population size (P), affluence (A), and technology (T), or I = P × A × T. Affluence and population size increase the environmental impact, while technology has the potential to reduce it [93,94,95,96].

UNCED, which became known as the Rio Earth Summit, also brought informal institutions into focus. In addition to the official negotiations conducted by the world’s governments, an entire tent city of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) held its own meeting [97]. The NGOs challenged the focus on population growth and tackled tough issues like lifestyles, per capita resource use and emissions, attitudes toward nature, and more. Some of the recommendations found their way into an ambitious implementation agenda called Agenda 21—the Agenda for Environmentally Conscious Development in the 12st Century [98]. Yet, the lack of formal institutions with global enforcement power rendered Agenda 21 rather ineffective.

UNCED was followed by the Kyoto Protocol, which was adopted in 1997 in Kyoto, Japan [52]. Kyoto was the world’s first internationally binding climate agreement and aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to 5% below 1990 level. It also required ratification by at least 55 countries and at least 55% of total CO2 emissions. Some major emitters exceeded these commitments, while the U.S. and Canada signed the Kyoto protocol, but did not ratify it. Kyoto covered six main greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). Its overall success has been mixed. CO2 reductions have been encouraging, yet reductions in N2O have been negligible and other greenhouse gases increased.

The so-called Paris Climate Accord was issued in 2016 on an optimistic note, as almost all of the world’s 197 nations signed the agreement. One of its key objectives was to keep global average temperatures at less than 2 °C above pre-industrial levels while aiming to achieve less than 1.5 °C. These goals required quick action to “achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks” in the second half of the 21st century [99]. To date, 179 of the undersigned countries have adopted climate proposals and strategies to enforce them. By 2018, the U.S. announced its withdrawal from the agreement, and while it rejoined in 2022, it is expected to withdraw again in the near future. Several U.S. states and municipalities, however, have maintained their climate commitments and implemented policies despite the lack of federal support.

Given the lack of formal institutions with enforcement power at the global level, non-compliance with global climate commitments has no real repercussions. Yet, the costs of climate-related disasters are growing and may soon outweigh the benefits of business as usual, even for those who have benefited from inaction. In December 2024, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in De Hague weighed in and held a hearing on the obligations of States vis a vis climate change [100]. In total, 96 nations and 11 non-governmental organizations presented their perspective on the nature and scope of climate law, international law, and the obligation of nation states.

Some may see this as a significant step toward global climate action, yet others caution that global institutions may not hold the best promise for action. The so-called trilemma of globalization suggests that countries cannot simultaneously maintain national sovereignty, globalization, and democracy [101]. Like global markets, global agreements may create desirable conditions, yet they may undermine domestic policies and challenge democratic decision processes. To resolve this trilemma, Rodrik and others propose a strategy of democracy-enhancing globalization as opposed to hyper-globalization. Hyper-globalization justifies rules that restrict national policies in the name of global ones; democracy-enhancing globalization affirms the sovereignty of legitimate democratic institutions and seeks to harmonize national policies instead of overriding them [101,102,103]. This points to the role of informal institutions in advancing global solutions.

5.2. Informal Institutions and Climate Change

Informal institutions represent less formal arrangements. They assert their influence through persuasion and appeal to social and cultural norms rather than signed agreements. Informal institutions can shape behavior just as much as formal ones. As a society’s informal institutional mindsets change, so will its formal institutional arrangements and vice versa. Political scientists describe this change process as memetic institutionalism [104,105]. The term suggests that policy actions evolve from an institutional environment similar to an organism evolving from its environment. Informal institutions, therefore, have the potential to support or hinder the adoption of formal policies [106,107,108]. Economists and public-choice theorists have also turned to game theory to study how institutions evolve and how norms and behaviors change [109,110,111].

Even as formal institutional arrangements like the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) asserted their global influence, informal institutions may still reflect the cultural characteristics of a region or community [112,113]. The Japanese market economy, for example, is different than the market economy of the U.S., Germany, and Sweden. These regional characteristics have policy implications. Germany and Sweden might argue that the role of policy is to protect individuals and social norms from the overreach of the market economy, while the U.S. might argue that the role of policy is to protect the market economy. Yet, as global agreements that supersede local and national regulations expand, informal institutional mindsets also tend to converge. German businesses no longer close mid-day, for example, and a 3-h lunchbreak is no longer the norm in Spain. Resistance to the homogenizing pressures of global economic mindsets, however, also seems to grow. The year 2019 was described as “the year of the street protester” [114]. Some of the observed protests articulated discontent with the advancing mindset of standard economics. The four underlying principles of economic theory that were previously discussed may illustrate this discontent.

5.2.1. Reclaiming Time

In her best-selling book ‘The Overworked American’, the economist Juliet Schor explored the time demands of the consumer-driven market economy [115]. She argued that in working to meet their needs and wants, American workers have increasingly reduced their leisure time despite growing productivity rates. The average American worker worked an additional 163 h annually or one additional month each year between 1970 and 1990, and the trend has continued. One of the reasons for the increase, often worked in multiple jobs, was the growing pressure to maintain or raise a standard of living shaped by material wants. This challenges the notion that technological advancements and productivity increases naturally lead to more leisure time.

Schor also documented the vicious cycle that drives Americans to spend more and more of their income on consumer goods, which leads to financial stress and the need to work longer hours as well as the need to spend more time on maintaining the accumulated consumer goods [116]. Schor described this as evidence that Americans are not only over-worked but also over-spent. She concludes that consumer societies need to reevaluate the work–life balance of their citizens and adopt measures of well-being rather than relying on the monetary measures of economic output and consumption.

These recommendations resonate with studies that show no clear evidence between increased consumption and improved well-being [117,118]. To be sure, the world’s poor need the means to meet their basic needs and a basic standard of living. Yet, the world’s most affluent societies seem to have moved beyond the point where an increase in material goods creates an increase in well-being.

Especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a shift in time preferences toward more flexibility and time spent at home rather than at work. As some reevaluated their priorities in search of a better work–life balance, the so-called “Great Resignation” was triggered, which saw a surge in resignations and new forms of work [119]. The exodus from the workforce indicates a shift in attitudes toward work and a desire to reclaim time for non-work-related activities and leisure time.

5.2.2. Reclaiming Place

The importance of place is especially evident in the food sector. In the United States, the country that leads the world in market concentration, superstar agribusinesses, and over-processed food, local food initiatives are emerging in virtually every region [120]. According to the USDA, U.S. farmers markets grew more than three-fold between 1990 and 2020. The face-to-face interaction they offer makes room for expressions of value beyond those captured in product prices [121].

Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) also experienced substantial growth. CSAs provide consumers with fresh, locally grown food while providing farmers with direct marketing opportunities [122,123]. Instead of buying food by the pound or volume, consumers pay an annual or seasonal fee to buy a CSA share of produce. In return, they receive freshly harvested vegetables, fruits, herbs, and flowers from local farms throughout the growing season. Deliveries of the CSA shares are typically scheduled weekly, and the size of the delivery depends on the harvest. This allows CSA farms to share some of their production risks with CSA member households. By 2020 almost 180,000 of the 2 million U.S. farms produced and sold food locally and generated over USD 9 billion in revenue [124]. Beyond buying and selling food, food economies are webs of activity, resources, and people that cut across many sectors of the economy, including hospitality, tourism, food processing, and technology as new production methods like hydroponics and aquaponics emerge, where food is grown in nutrient rich water rather than in soil. The growing interest in local food options, therefore, has a larger economic impact than what is captured in the direct sale of fresh food [125,126].

The recent COVID pandemic added to the growing interest in local food. Some food items became unavailable during the pandemic as workers in meat-packing plants, for example, suffered from high infection rates and migrant farm workers were unable to reach their farms to harvest crops [127,128]. Since the pandemic, rising energy costs, inflationary pressures, and climate-related shock events have continued to drive the demand for more local food.

5.2.3. Reclaiming Context

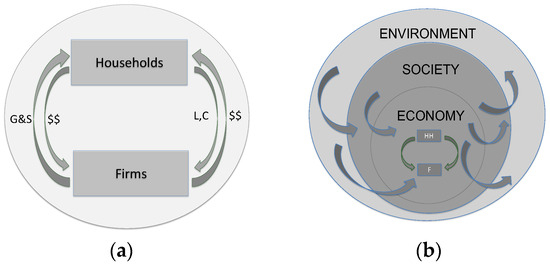

An alternative to the dominant market economic model is restorative economics [129,130]. It recognizes that economic activity does not take place in isolation (Figure 1a) but is instead dependent on social and environmental context systems (see Figure 1b). Economic activity impacts the social and environmental contexts that deliver labor and natural resources and receive emission and waste by-products in return. The health and vitality of social and environmental context systems, in turn, impact the economy. If workers are exhausted and natural resources are depleted, the productivity of the economy is reduced. Restorative economics recognizes these connections.

Figure 1.

Standard economic model (a) and restorative economic model (b) [86].

Restorative economics also brings the value of sink functions into view. Sinks absorb and process the emissions and waste by-products of economic activity. Oceans, for example, are sinks that absorb the carbon emissions that are the by-product of producing energy and transporting goods around the globe; soils are sinks that absorb nitrogen and prevent nitrates from contaminating the groundwater; urban gardens and green roofs are sinks that absorb stormwater runoff and protect aquifers; forests are carbon sinks and provide oxygen. Losing these sink capacities is as or more costly as losing valuable resources like labor and energy.

The cost of lost sink capacities extends not only to environmental sinks but also to social sinks. Our human bodies act as sinks and absorb vitamins, nutrients, sugar, and salt, but also pesticides, micro-plastics, and carcinogens. Human communities act as sinks that support individuals and thus reduce the likelihood of illness and stress. When the health and vitality of a community is impaired, the physical, mental, and emotional health of its members deteriorates, and stress syndromes increase.

As feminist scholars and ecological economists have long pointed out, marginalized populations have carried a disproportional share of the burden of overused sinks [68,131,132]. This makes it challenging to gain acceptance for the value of sink capacities. Yet, neglected sinks like the earth’s atmosphere are not only valuable but vital. Their loss carries enormous costs that may finally draw attention to the valuable services provided by social and environmental context systems.

5.2.4. Reclaiming Growth

Ecological economists were some of the first to question the unlimited growth paradigm of standard economics. Works like Dennis and Donella Meadows’ ‘Limits to Growth’ [133,134], E.F. Schumacher’s ‘Small is Beautiful’ [135], Kenneth Boulding’s ‘Spaceship Earth’ [136], and Herman Daly’s ‘Steady State Economics’ [137] run counter to the unlimited growth assumptions of standard market economics. Daly, for example, argued that the three big questions of economics, namely what to produce, how to produce it, and for whom to produce it, must be amended by the question of how much to produce. Similarly, Schumacher argued “…since consumption is merely a means to human well-being, the aim should be to obtain the maximum of well-being with the minimum of consumption…” [138].

A systematic review of the literature on economic degrowth concluded that the movement has grown substantially [139] and follows two main tenets: one suggests that growth can be reshaped into a greener version (green growth); the second suggests that growth is altogether undesirable (degrowth). Proponents of green growth argue that it is possible to achieve qualitative growth that stays within planetary boundaries [140,141]. Degrowth or zero-growth proponents argue that an economic system that is focused on growth is antithetical to respecting planetary boundaries [142]. The economists Nicolai Georgescu-Roegen, for example, argued that a shift away from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources that protect planetary boundaries will require a decrease in energy consumption and thus degrowth [143,144].

Another degrowth model is the doughnut economy model, which seeks to balance human needs with planetary boundaries [145]. It provides the conceptual framework for determining whether a region operates within (inside the doughnut) or beyond (outside of the doughnut) planetary boundaries and identifies pathways for adjusting to a region’s boundaries.

Much of the degrowth literature has been conceptual, yet there is a growing body of empirical work that is largely case study-based and focused on local and regional degrowth initiatives. Efforts are also underway to explore new institutional models that promote local and regional partnerships around implementing planning tools like the net-zero carbon roadmap, for example [146]. The map assists local decision makers in designing and implementing climate actions that attain net-zero carbon emissions.

A recent macro-level study examined the connection between the global hydrological cycle and economic output measured in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for five major economies: the United States, China, Germany, Russia, and India. Collectively, these five countries account for approximately 60% of the global GDP and 40% of the world’s population. By calculating the amount of energy available for freshwater evaporation and the allocation of freshwater to domestic, industrial, and agricultural uses, the study found that the hydrological cycle impacts the economic capacity of all five countries. It further showed that the non-use of water is as valuable (or more) as its use for all five countries. This runs counter to the premise of standard economics, which assumes that the use of resources in the production process drives value and resources used for economic production are therefore more valuable than conserved resources [86].

These challenges to the standard economic view of time, place, context, and growth indicate that a change in mindsets is underway despite the dominance of standard market economics. Local climate change movements have grown significantly over the past twenty years and include both loose local and regional climate networks and formal partnerships. The Climate Reality Project, for example, founded by former U.S. Vice President Al Gore in 2005, has grown to a global network of 3.5 million supporters in 170 countries [147]. Growing challenges to the dominance of the standard economic model are also evident in the UK, where 62% of all local authorities have a climate action plan in place [148]. The drive behind the informal institutional mindsets emerging around the globe seems to be bottom-up localized initiatives that crop up despite a lack of formal institutional commitments to a revised economic agenda.

5.3. Climate Change Policies

Policies are systems of formal rules and principles that seek to balance social and individual goals and ideally achieve the best outcome for society at large. Policies live in the space between formal and informal institutions. The aim of climate change policies, for example, is to halt climate change despite the fact that global institutions lack legislative authority. Global corporations, in contrast, can act across national boundaries and can assert their influence at the local, national, and global level.

This illustrates the importance of building support through informal institutional arrangements. By making informal institutional mindsets transparent, social and cultural norms that support climate friendly policies can gain visibility. Engaging local communities in collaborative efforts with others who share common mindsets can therefore identify viable pathways that increase the effectiveness of local and regional policies and create positive spillover effects beyond [149]. Technology and social media make it possible for local and regional organizations to share information and collaborate with unprecedented ease. Local communities can therefore share information about effective climate mitigation efforts and ways to reduce unintended side-effects. This is all the more important as the complexities of climate change are prone to invite unintended consequences. The State of California, for example, enacted an incentive policy that rewards those who purchase a hybrid vehicle with a USD 1500 tax credit. It also enacted a law that allows hybrid cars to use high-occupancy vehicle lanes on state highways that are usually restricted to vehicles with multiple passengers [150]. The combination of the tax credit and the highway use policy succeeded in increasing hybrid vehicle ownership. It remains to be seen, however, if the dual incentives will reduce public transportation ridership. This would reduce the overall benefits of the policy and might even increase the net carbon emissions.

The policy cycle is an analytical tool that can assist policy makers in analyzing the complexities of a proposed policy and assess its overall effectiveness. Several popular models suggest six to eight stages of the cycle. Anderson’s cycle was first introduced in 1974 and suggests six stages [151,152,153]:

- Agenda setting—identifying a problem and recognizing that government intervention is needed.

- Policy formulation—exploring and assessing various alternative policy options to address the problem.

- Decision making—the government and its respective governing bodies decide on an ultimate course of action.

- Implementation—putting into action the final decision regarding the best course of action.

- Evaluation—assessing the effectiveness of a policy in terms of its intended versus actual results.

- Action—determining whether the adopted course of action is a success and examining whether and what course corrections are needed.

Using policy tools like the Anderson cycle, local and regional collaborators can create and expand what Wallner and others called ‘Islands of Sustainability’ [154]. These Islands are localities and regions that succeed in implementing effective social and environmental sustainability practices even when they are surrounded by unsustainable practices. Key characteristics of the Islands of Sustainability include (1) sustainable practices across such diverse sectors as energy, agriculture, waste management, and tourism; (2) reduced environmental impacts while promoting social equity and economic viability; (3) serving as testing sites for innovative solutions to environmental problems; and (4) committing to protecting unique ecosystems.

An example of an effective regional collaboration across international boundaries is the Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC), which is a collaborative of thirteen local governments that serves a population of approximately 2.5 million close to Washington DC. The NVRC’s international collaborations focus on transferring and applying policy and technology innovations from pioneering communities around the world that benefit NVRC members communities. In its 2025 report, NVRC wrote the following: “We live in a globally interconnected world. Phenomena like foreign trade and investment, climate change and cross-national immigration compel towns, cities, counties and regions across the United States and Virginia to respond in a strategic manner. Passive reaction by local and regional governments to global forces is no longer an option when addressing the issues of economic development, social inclusion or resiliency… By systematically searching and applying policy and technical innovations from pioneering metropolitan regions overseas, NVRC has advanced renewable energy, mobility, watershed restoration, green buildings and workforce training to the benefit of communities in Northern Virginia. It is an understatement to say that the economy and the environment of Northers Virginia have been positively transformed through NVRC’s international work” [155].

Similar examples exist around the world. The European Union Communities for Climate (C4C), for example, are a network of 50 communities across eleven EU countries [156]. Collaborators were selected to implement innovative climate actions with expert support. While local expertise is indispensable to the design and implementation of successful climate initiatives, technical expertise can save time and resources as communities share their various learning experiences. Roggero and others argue that climate change mitigation illustrates not only the limits of standard economic theory but also the potential for cross-boundary adaptation spillovers, where adaptation by one region or country can affect others. Cross-boundary spillovers could therefore render the climate mitigation efforts of smaller regions as more effective than expected [149,157,158]

Apart from testing the effectiveness of policy transfers, local and regional collaborations can lay bare the informal institutional mindsets that shape policy decisions and find new common ground. The NVRC report states, “Perhaps most relevant, NVRC’s singular focus on outcomes that strengthen Northern Virginia has created an uncommon acceptance for international work at the local and regional levels.” [155]. Forging local and regional collaborations across the globe can therefore identify more than technical expertise. It can instead identify the broader benefits of collaborating with others across the global commons. Scaling such local and regional initiatives can facilitate change at multiple levels and bring about institutional structures that mirror the biodiversity of ecosystems.

6. Conclusions

Five years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, I argued that the institution ‘economy’ would become the institutional equivalent of a monoculture that would imprint the mindset of standard market economics on institutions and cultures around the world [47]. The danger of this global expansion would be the erosion of social and cultural norms that can impose limits on market efficiency goals for the benefit of social and environmental goals. Climate change, in particular, if left unabated, would endanger the welfare of communities and ecosystems around the world.

Climate change is typically framed as a global example of public goods and externality failures. Both of these market failures acknowledge the limits of standard market economics to bring about the best outcome for society as a whole, or what economists call the social welfare optimum. Standard economic theory acknowledges that when market failures are present, policy interventions become necessary to restore the ideal of socially optimal outcomes.

Climate change has indeed advanced since the 1990s and has now reached catastrophic levels. Yet, my assumption about the impending economic monoculture of standard market economics was only partially correct. While the logic of standard market economics has expanded globally and has influenced the formal and informal institutions of countries and cultures around the world, new informal institutional mindsets are also emerging. These mindsets give rise to local and regional initiatives that utilize the power of markets as effective mechanisms for economic transactions while also challenging the underlying principles of standard market economics.

This article explored four of these underlying principles of market economics, namely its treatment of time, place, context, and growth, and showed how both theoretical work and practical initiatives challenge and reclaim these four principles. Making the assumptions of market economics and its limitations transparent creates new opportunities for collaboration and new pathways for more effective climate mitigation policies across local and national boundaries. Such collaborations are already underway and underscore the potential for smaller-scale local and regional efforts to bring about change beyond their spatial and institutional boundaries.

To be sure, formal institutions that mitigate climate change at the global level would be desirable. Yet, existing institutions lack effective enforcement mechanisms and it is not likely that more effective alternatives will emerge in the near future. Cross-boundary local and regional collaborations are therefore all the more important. Supporting the emerging mindsets that support effective local and regional efforts are therefore our best hope for progress toward mitigating climate change.

Evolution is a slow process. Yet, it is encouraging to see the emergence of local and regional initiatives that support global solutions. Understanding the informal mindset of market economics can support effective local and regional collaborations by making underlying principles transparent that run counter to the social and cultural norms that local communities seek to pursue based on their lived experiences. As the clock on climate change is ticking, all levels of governance are needed to create effective cross-boundary collaborations that can create positive spillover effects from one community and region to another. Markets are powerful mechanisms that must be a part of the solution. Yet, they are not sufficient. The emergence of more diverse institutional ecosystems may be the most promising pathway to sustaining the global commons including the human communities within it.

Funding

This research was not supported by external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data referenced in this article is publicly available and referenced.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest and has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced her work.

References

- Tol, R. A meta-analysis of the total economic impact of climate change. Energy Policy 2024, 185, 113922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, T.M.; Xu, C.; Abrams, J.F.; Ghadiali, A.; Loriani, S.; Sakschewski, B.; Scheffer, M. Quantifying the human cost of global warming. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, A.O.; Opoku, E.E.O. Environmental degradation and economic growth: Investigating linkages and potential pathways. Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, M. The Destruction of Nature Threatens the World Economy; UNEP: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, R.; Noy, I. The global costs of extreme weather that are attributable to climate change. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R. Positional Externalities Cause Large and Preventable Welfare Losses. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlman, C. The problem of externality. J. Law Econ. 1979, 22, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.A. Theory and Measurement of Economic Externalities; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. J. Nat. Resour. Policy Res. 2009, 1, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, T. Public Goods and Market Failures: A Critical Examination; Taylor & Francis: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, V.; Ostrom, E. Public goods and public choices. In Alternatives for Delivering Public Services; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 7–49. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.; Cobb, J. For the Common Good; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gowdy, J.; O’Hara, S. Economic Theory for Environmentalists; St. Lucie Press: Delray Beach, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Riordan, T.; Jordan, A. Institutions, climate change and cultural theory: Towards a common analytical framework. Glob. Environ. Change 1999, 9, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C.S.; Yeager, D.S. Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernecker, K.; Job, V. Mindset Theory. In Social Psychology in Action; Sassenberg, K., Vliek, M.L.W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. Die Regeln der Soziologischen Methode; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, E. Soziologie und Philosophie; Suhrkamp: Berlin, Germany, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, S. Political Order in Changing Societies; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1996; p. 9. ISBN 978-0-300-11620-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G.M. On defining institutions: Rules versus equilibria. J. Institutional Econ. 2015, 11, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, M. Toward a Comparative Institutional Analysis; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Greif, A. Historical and comparative institutional analysis. Am. Econ. Rev. 1998, 88, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Spiro, M.E. A typology of social structure and the patterning of social institutions: A cross-cultural study. Am. Anthropol. 1965, 67, 1097–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodanciuc, R. Social institutions. Ann. Univ. Petroşani Econ. 2012, 12, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Tuomela, R. Collective acceptance, social institutions, and social reality. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 2003, 62, 123–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Surgeon General. Our Epidemic of Loneliness; US Public Health Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dugan, A. Over 1 in 5 People Worldwide Feel Lonely a Lot: Loneliness Makes Other Negative Feelings Worse; Gullup Report; 10 July 2024. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/646718/people-worldwide-feel-lonely-lot.aspx (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Louv, R. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder; Algonquin Books: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bowler, D.E.; Buyung-Ali, L.M.; Knight, T.M.; Pullin, A.S. A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.; Van Wieren, G.; Zaleha, B.D. Lynn White Jr. and the greening-of-religion hypothesis. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northcott, M. The Environment and Christian Ethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, J. A Christian Natural Theology, 2nd ed.; Westminster John Knox Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Oreskes, N.; Conway, E. From Anti-Government to Anti-Science: Why Conservatives Have Turned Against Science. Daedalus 2022, 151, 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutjens, B.T.; Sengupta, N.; Der Lee, R.V.; van Koningsbruggen, G.M.; Martens, J.P.; Rabelo, A.; Sutton, R.M. Science skepticism across 24 countries. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2022, 13, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M. Making sense of the spectrum of climate denial. Crit. Policy Stud. 2019, 13, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulianne, S.; Belland, S. Climate denial in Canada and the United States. Can. Rev. Sociol./Rev. Can. Sociol. 2022, 59, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harold, J. Understanding the Crisis in Institutional Trust; Urban Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Justino, P.; Samarin, M. Social Cohesion and the Social Contract in Uncertain Times; United Nations University World Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Boyer, P. Human Cultures Through the Scientific Lens: Essays in Evolutionary Cognitive Anthropology; Open Book Publishers: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teraji, S. Understanding coevolution of mind and society: Institutions-as-rules and institutions-as-equilibria. Mind Soc. 2017, 16, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. The rise and decline of general laws of capitalism. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.A.; Acemoglu, D. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty; Profile: London, UK, 2012; pp. 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Economy and Society; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, S. Valuing Socio-Diversity. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 1995, 22, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampike, U. Neoklassik und Zeitpraeferenz: Der Diskontierungsnebel. In Die Oekologische Herausforderung fuer die Oekonomische Theorie; Beckenbach, F., Ed.; Metropolis: Marburg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, K. Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tietenberg, T. Environmental and Natural Resource Economics, 2nd ed.; Scott, Foresman: Boston, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. The Institutional Aspects of Peasant Communities: An Analytical View. In Energy and Economic Myths; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Dec. 10, 1997, 2303 U.N.T.S. 162. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/what-is-the-united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Chichilnisky, G.; Hammond, P.; Stern, N. Fundamental utilitarianism and intergenerational equity with extinction discounting. Soc. Choice Welf. 2020, 54, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichilnisky, G. Climate Policy Without Intertemporal Dictatorship: Chichilnisky Criterion Versus Classical Utilitarianism in Dice; 2017; pp. 1–16. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/88757/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Nordheim, H. Conceptual History between Chronos and Kairos—The Case of “Empire”. Redescriptions Political Thought Concept. Hist. Fem. Theory 2007, 11, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.J. Space, Place and Scale: Human Geography and Spatial History in Past and Present. Past Present 2018, 239, e23–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, G.E. Of place, creation, and relations. In Finding Our Place; O’Hara, S., Ed.; Ecojustice Quarterly; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara, S. Reclaiming Local Contexts: Disrupting the Virtual Economy. In Research Agenda for Critical Political Economy; Dunn, W., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.O. The Diversity of Life; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fresque-Baxter, J.A.; Armitage, D. Place identity and climate change adaptation: A synthesis and framework for understanding. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2012, 3, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger-Ross, C.L.; Uzzell, D.L. Place and identity processes. J. Environ. Psychol. 1996, 16, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, R. We thinking and its consequences. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A.; Kranton, R.E. Identity economics: How our identities shape our work, wages, and well-being. In Identity Economics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kranton, R.E. Identity economics 2016: Where do social distinctions and norms come from? Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Jeon, J.; Ramalingam, A. Identity and group conflict. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 90, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook-Huffman, C. The role of identity in conflict. In Handbook of Conflict Analysis and Resolution; Sandole, D., Byrne, S., Sandonle, I., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fearon, J.D.; Laitin, D.D. Violence and the social construction of ethnicity. Int. Organ. 2000, 54, 845–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, S. Everything Needs Care: Toward a Relevant Contextual View of the Economy. In Counting on Marilyn Waring: New Advances in Feminist Economics; Bjørnholt, M., McKay, A., Eds.; Demeter Press: Bradford, ON, Canada, 2014; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, M. Ecofeminist political economy. Int. J. Green Econ. 2006, 1, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikliras, A.C.; Froese, R. Maximum sustainable yield. Encycl. Ecol. 2019, 1, 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V.L. Economics of production from natural resources. In Economics of Natural & Environmental Resources (Routledge Revivals); Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 309–331. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, R.H.; Gilovich, T.; Regan, D.T. Does Studying Economics Inhibit Cooperation? J. Econ. Perspect. 1993, 7, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, J.M. The Bioethics of Hunting and Gathering Societies. Rev. Soc. Econ. 1992, 50, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diwan, R.; Lutz, M. Essays in Gandhian Economics; Gandhi Peace Foundation: New Delhi, India; New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlins, M. Stone Age Economics; Aldine-Atherton: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Diwan, R. Gandhian economics: An empirical perspective. World Futures 2001, 56, 279–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.B.; Branco, J.H.L.; Martins, T.B.; Santos, G.M.; Andrade, A. Impact of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of university students and recommendations for the post-pandemic period: A systematic review. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2024, 43, 100941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, I.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Ganz, F.; Torralba, R.; Oliveira, D.V.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L. Impact of Social Isolation Due to COVID-19 on Health in Older People: Mental and Physical Effects and Recommendations. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.J.; Rabheru, K.; Peisah, C.; Reichman, W.; Ikeda, M. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2020, 32, 1217–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, A.; Wang, R.; Behrens, P.; Hoekstra, R. Beyond GDP: A review and conceptual framework for measuring sustainable and inclusive wellbeing. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e695–e705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, S.; Sharma, N.; Dhayal, K.S.; Esposito, L. From economic wealth to well-being: Exploring the importance of happiness economy for sustainable development through systematic literature review. Qual. Quant. 2024, 58, 5503–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.H. Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 1939, 29, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kharas, H.; Fengler, W. Double Tipping Points in 2019: When the World Became Mostly Rich and Largely Old. Brookings Institution. Wednesday, 9 October 2019. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/double-tipping-points-in-2019-when-the-world-became-mostly-rich-and-largely-old/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Hartwick, J.M. Intergenerational Equity and the Investment of Rents from Exhaustible Resources. Am. Econ. Rev. 1977, 67, 972–974. [Google Scholar]

- Asheim, G.; Buchholtz, W.; Hartwick, J.; Withagen, C. Constant Saving Rates and Quasi-arithmetic Population Growth under Exhaustible Resource Constraints. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 53, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, S.; Kakovitch, T.S. Water as driver of economic capacity: Introducing a physical economic model. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 208, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Geneva, UN-Dokument A/42/427. 1987. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Scruggs, G. Canada, U.S. negotiate future of Columbia River in Seattle this week. Seattle Times, 11 August 2023. Available online: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/environment/canada-u-s-negotiate-future-of-columbia-river-in-seattle-this-week/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Mahler, R.; Barber, M.; Simmons, R. 20 Years of Progress: How the Regional Water Resources Program in the Pacific Northwest (USA) Reduced Water Pollution. Int. J. Environ. Impacts 2020, 3, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IKSR Rhine 2020—Programme on the Sustainable Development of the Rhine. Brussels. 2020. Available online: https://www.iksr.org/fileadmin/user_upload/DKDM/Dokumente/Broschueren/EN/bro_En_Assessment_“Rhine_2020”.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).